Tech Talk - The Oil and Gas of Southern Alaska

Posted by Heading Out on August 21, 2011 - 6:32am

Russian visitors had already noted the presence of oil seeps in Alaska, although they had not done anything about it by the time the tsar sold the land to America on March 30, 1867. Russian history would have it that some $165,000 of the $7.2 million of the sale was used to persuade doubting American legislators and members of the media of the value of the purchase. The oil can still be seen coming from current seeps such as this one:

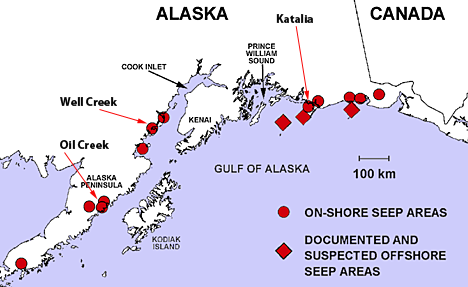

These seeps occur both on and offshore, and as happened in the rest of the country, it was these seeps that brought prospectors to the region and where the first wells were drilled.

It is pertinent to note that the creeks shown above are productive salmon spawning grounds, though it was the oil that led to early development.

The first producing field was at Katalia on the Gulf of Alaska. Discovered in 1902, it produced 154,000 bbl of oil before the refinery burned in 1933.

The larger fields in and around the Cook Inlet began production with the development of the Swanson River field in 1957. The first Alaskan pipeline was built in 1960 to carry oil from there to the Nikiski refinery (which later supplied the fuel to the International Airport in Anchorage). The Cook Inlet fields peaked in oil production, at 227,400 bd, in 1970. The largest oil field in the region was the McArthur River field, discovered in 1965, but while discoveries continue to be made, the majority of the wells are now past their prime and will need significant work to be brought back into production. The more recent developments were offshore, with a considerable change in structure from that of the early days.

In 1958, natural gas was discovered in the Kenai Peninsula and by 1962, was supplying gas to Anchorage, 85 miles away. There was sufficient natural gas available that, in 1969, a liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant was built and began shipping LNG to Japan, the first such export from the US to Asia. By 2009, some 1300 tanker loads, with an original deadweight capacity of 36,896 tons, had been shipped through that train.

There were two original tankers on the run, the POLAR ALASKA and the ARCTIC TOKYO, partially made of balsa wood and invar steel and they made the twenty-one day round trip until 1993, when they were replaced by the POLAR EAGLE and the ARCTIC SUN, each with a deadweight of 87,000 metric tons. The ships were renamed POLAR SPIRIT and ARCTIC SPIRIT at the end of 2007, when the registration was moved from Liberia to the Bahamas. They were sold to Teekay Corporation at that time, but leased back for the duration of the project. With the declining production from the plant, the ARCTIC SPIRIT was returned to its owners in April, 2009.

The recent drop in the price for LNG on the world market meant that the POLAR SPIRIT was returned to its owners at the end of of the original charterthis past April. It now appears to be shuttling between Yokahama and the China Sea, with the last call in the US being in June. The LNG facility was mothballed at the beginning of this summer since Alaskan LNG was no longer competitive on the market.

. . . the plant received needed license extensions last year, but was not able to get a satisfactory price for their LNG . . . business case does not support continuing exports at this time.

The original two LNG carriers were renamed SCF POLAR (which left Las Palmas a couple of days ago) and SCF ARCTIC which left Point Fortin this morning.

The region has never been one of intense activity, with only a relatively few wells being drilled in any one year.

At present there are two jack-leg drills heading for Cook Inlet, with the state providing some of the funding ($30 million) for this new drilling activity.

The wells that have been drilled and brought into production in the past have produced, to date, around 1.3 billion barrels of oil, 7.8 trillion cubic ft (TCF) of natural gas and 12,000 bbl of natural gas liquids in total. At the end of June, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) announced the results of a new assessment of the resources of the region. There is a considerable amount of coal in the region, which is likely to contain methane, and this is now included.

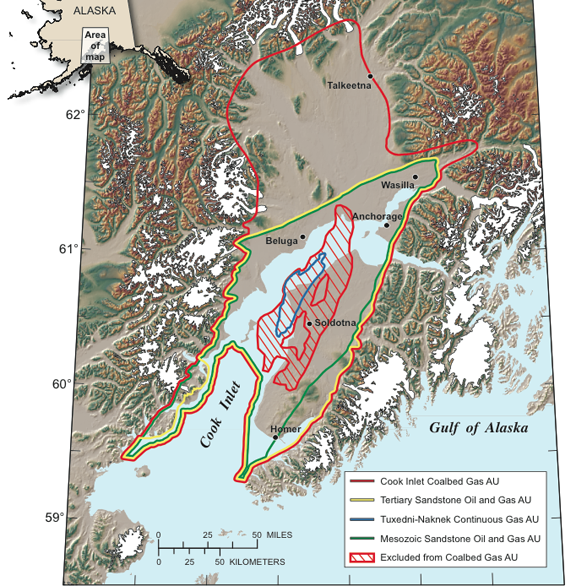

The excluded region in the above graphic shows the coal that lies below 6,000 ft, and is considered unlikely to hold any gas. In addition to this coalbed methane, the USGS re-evaluated the likely volumes held in the sandstone and conglomerates that have, to date, been the host rocks for the oil and gas that have been extracted. Finally, the USGS assessed the potential of tight sands in the region to hold technically recoverable volumes of gas.

As the recent experience with natural gas has shown, just because a resource exists and can be recovered does not mean that it will make sufficient money to justify the investment in the extraction. Thus the USGS can only say that there is a significant likelihood of oil and gas being present and recoverable, without bringing the costs and price of the fuels on the market into the discussion, and thus defining whether the resource is, or will be a reserve, or not.

Because the volumes are estimates, they vary from it being a 95% chance that there is some 5 Tcf of natural gas available, to a 5% chance that there is 39 Tcf of natural gas present. In the same way, they estimate that there is a 95% chance of 108 million barrels of oil (mbo) being present, while there is a 5% chance that there might be as much as 1.3 billion barrels. Unfortunately, current prices are not necessarily favorable to much exploratory drilling to validate some of those numbers, though obviously they are favorable enough to convince the Governor to put up some money.

But another part of the reason for this lack of interest has been because of the much larger volumes of Alaskan oil that lie considerably further north in the region known as the North Slope, which I will discuss next time. But that is beginning to run out, and there are other problems that are apparent, so the resources further south may have thus become more attractive.

Incidentally, the mothballing of the LNG plant is leaving Anchorage with a wee bit of a problem. Until this year, the facility has acted as a transient storage facility from which, in periods of high demand (such as the depth of winter), gas could be temporarily withdrawn to make up temporary shortages between demand and supply from the wells in the field. That has now gone.

As the recent experience with natural gas has shown, just because a resource exists, and can be recovered, does not mean that it will make sufficient money to justify the investment in the extraction. Thus the USGS can only say that there is a significant likelihood of oil and gas being present and recoverable, without bringing the costs and price of the fuels on the market into the discussion, and thus defining whether the resource is, or will be a reserve, or not.

That seems critically important, in this whole "peak oil" scenario: the costs get so high that the flagging economy won't support keeping up the oil supply, so oil prices sag, with simultaneous recession.

I have a question concerning geology. I wouldn't expect a subduction zone to be an oil/gas province. Is there enough organic seafloor sediment scraped off at the plate boundary to allow some hydrocarbons? [Obviously something like this must be true.] What does this mean for the other subduction zones around the north Pacific?

EOS - I'm far from a wesr coast geologist but I won't let that stop me. The Pacific plate is sliding under the N American plat but that's occuring 100's of miles west of the current shoreline. Onshore CA oil fields are producing from relatively young sediments that accumulated on this undisturbed "shelf". The porous and productive sediments eroded off the mainland and weren't scraped up off the occeanic plate.

Certainly lots of organics deposited out in those deep waters. What's lacking are reservoir quality rocks. And then you need the thermal history to make the hydrocarbons. Does heat up as they are subducted but still don't have the reservoir rock. Possibly some of those hydrocarbons are the source of some of the west coast fields if they leaked all the way up. But I'll leave that theory to the geologists out there. But subduction zones can contribute to an oil province indirectly by pushing up the edge of the continental plate forming structural traps for hydrocarbons to accumulate: witness the fields along the onshore streches of S CA.

There you go...told you about 200% of what I understand about west coast geology. Good luck with that.

Rockman has it more or less right. Cook Inlet is what is refered to as a "forearc basin". As the plate is pushed under mainland Alaska, it creats a sort of a bulge, between the subduction zone and the mountain arc further inland. Between the bulge and the mountains is a low area called a forearc basin. This basin is inland of the trench. Some of the sediment eroded off of the mountains gets trapped in this basin, rather than carried out to the trench. The Central Valley in California (which also produces oil) is a somewhat similar forearc basin. I have to get offline now, but if you are still interested I can later today try to dig up some online references.

EOS--Alaska Geo and Rockman are correct. I'll add that if you look at the coal map in the post, note the intense topography of the mountains around the Cook Inlet, and then the flat gray (and water) of the Cook Inlet region (which includes Wasilla and Talkeetna farther north). This flat gray topography (on the map) describes a depositional plain, where sediment eroded from the mountains (as described by Alaska Geo) has been deposited. Hydrocarbon basins tend to be just that, depositional areas for sediment eroded across a very wide watershed. The Gulf of Mexico (and nearby states of Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma) is exactly that, containing over a hundred million years' of accumulated sediment from rivers such as the Mississippi, Rio Grande, and their ancestors. Organic material is deposited and buried, cut off from oxygen, more quickly than it can decompose. It thus becomes the raw material for hydrocarbons.

I was wondering if you had any plans to address Northern Alaska coal resources in a future post. I would love to see an in-depth analysis of how much coal is up there, how easily recoverable it is, technical difficulties etc. It seems like a big unknown in our energy future.

I wasn't, but I will take another look at the possibility. Only problem is that on the day I was supposed to visit the mine I played hookey and drove up the Dawson Highway to the Yukon instead.

Hi HO,

I guessing the mine you were to visit was the Usibelli family operation at Healy, the only commercial coal mine I'm aware of up here. Their operation is located on the northern slope of the Alaska Range, just a short ways from Denali Park. When people speak of the northern Alaska coal resource they are usually talking of the huge but barely defined lower grade coal deposits on the north slope of the Brooks Range well west (hundreds of miles) of the famed North Slope oil province.

Yes Anchorage could have some natural gas issues with the Nikiski plant's closure. They were already talking about importing LNG as the Cook Inlet's production has been falling off. Of course the new gas estimates for the region have all kinds of poorly informed people talking about the a great gas conspiracy.

I don't know if I will have a chance to get back to this discussion. Have to roll out at about 3AM to get to Delta Junction in time to catch the shuttle onto the fort. Not sure what sort of internet or phone access will be allowed there.

While the LNG plant closure represents a storage problem for Anchorage, it also potemtially represents a solution to the supply shortfall which has had folks talking about a 'bullet line' from the North Slope.