Where the Rubber Meets the Road: Ecological Economics and Intensive Vegetable Cultivation

Posted by nate hagens on March 14, 2008 - 9:22am

"Can we rely on it that a ‘turning around' will be accomplished by enough people quickly enough to save the modern world? This question is often asked, but whatever answer is given to it will mislead. The answer "yes" would lead to complacency; the answer "no" to despair. It is desirable to leave these perplexities behind us and get down to work." E.F. Schumacher, Small is Beautiful

I would rather have titled this essay "Where the Hoe Meets the Soil" but that phrase is not part of our cultural lexicon, which is itself a symptom of the problem I am working to address. Setting aside any prolonged discussion of whether or what about the modern world should be saved, this essay is primarily about what it means to "get down to work" as Schumacher puts it. But very quickly, to me saving the modern world means setting a goal for the human economy to be properly scaled relative to the global ecology, and maintaining a sufficiency of social stability necessary to manage a transition.

Before getting to work, I want to make sure the work I do is useful. This is where a clear understanding of the big picture helps.

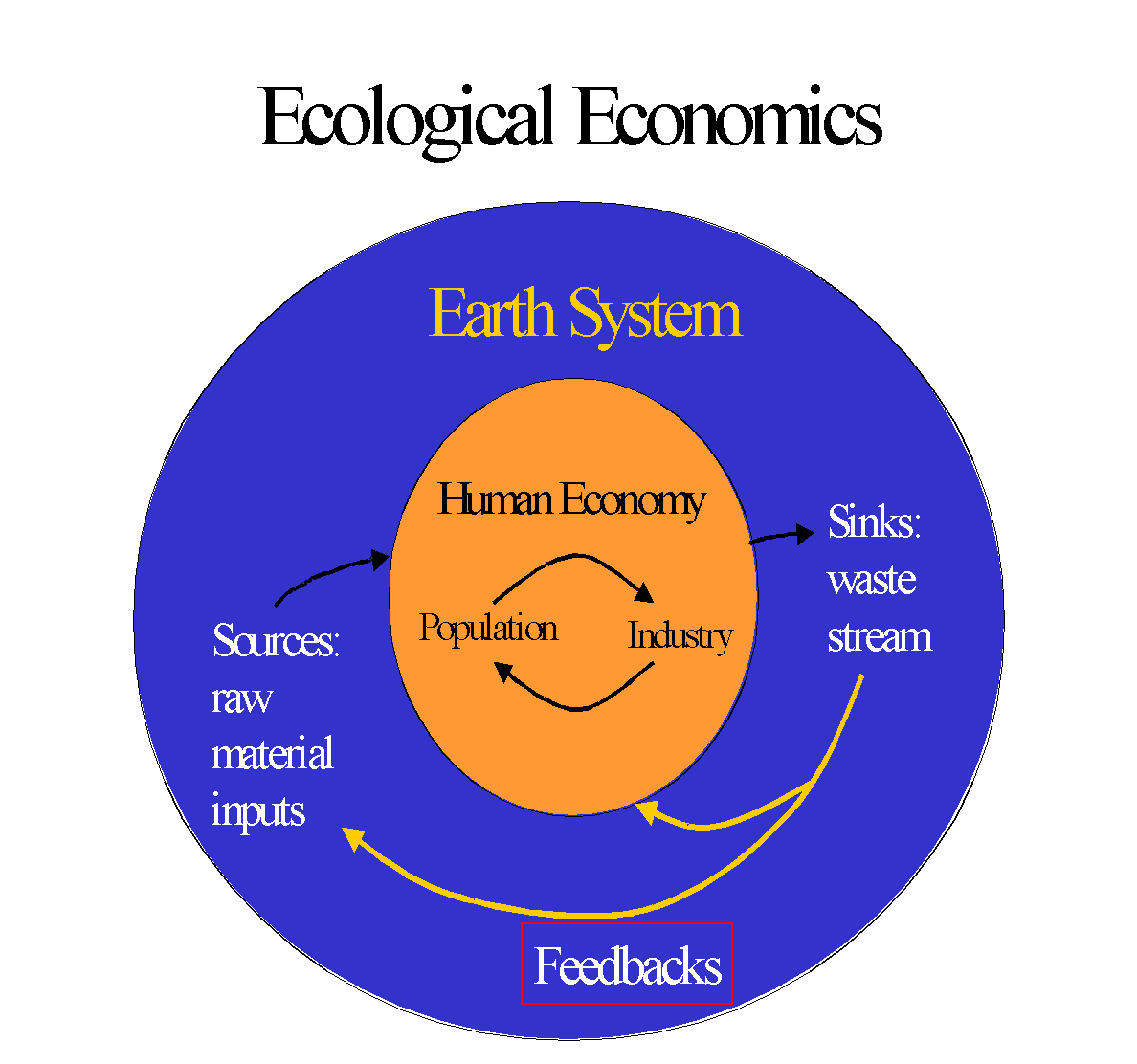

Ecological Economics

The question of proper economic scale is examined by the field of ecological economics. In the ecological economics model, the human economy is a subset of the Earth system, and therefore the scale of the human economy is ultimately limited. The human economy depends upon the throughput or flow of materials from and back into the Earth system. Limits to the size of the human economy are imposed by the interactions among three related natural processes:

(1) The capacity of the Earth system to supply inputs to the human economy (Sources),

(2) The capacity of the Earth system to tolerate and process wastes from the human economy (Sinks), and

(3) The negative impacts on the human economy and the resources it relies on from various feedbacks caused by too much pollution.

"

"

Fig. 1. The ecological economics model of the relationship between the human economy and the Earth system highlighting the importance of sources, sinks, feedbacks and scale.[i]

For an expanded look at the relationship between our economy and the planet see the engaging on-line film "The Story of Stuff."[ii]

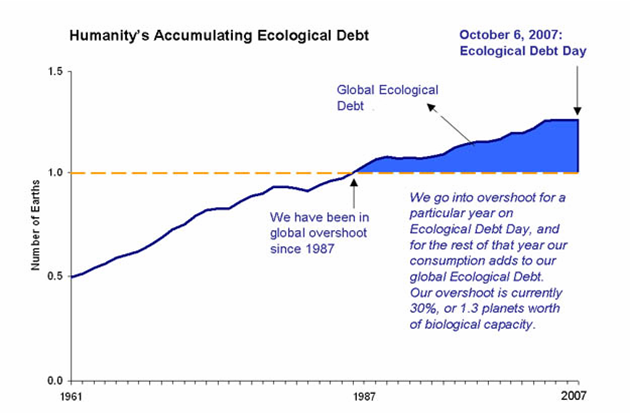

One measure of whether the human economy is too large is the ecological footprint (EF), which calculates on a nation-by-nation basis the consumption of resources and the build-up of wastes relative to resource regeneration rates and the waste-absorbing capacity of the environment. According to two independent EF analyses (which I will call EF 1 and EF 2) the human economy (population plus consumption and waste generation) is in a state of overshoot, meaning it is too large relative to the long-term capacity of the planet to cope.[iii] The Earth can provide for us beyond its means for a long time before the consequences become severe, just like a millionaire can, for a time, live high on the principal in a savings account instead of the interest. The degree to which we are drawing down principal as opposed to living on interest is called our "ecological debt."

Figure 2. Change in ecological footprint over time according to EF 1 with our cumulative ecological debt in blue.[iv]

Indicators like the ecological footprint are important for understanding we have a problem and giving us a sense of the scale, but they aren't very specific. In order to do something about reducing our footprint, it would help to know what is causing the ecological footprint to be so large. A significant portion of the ecological footprint represents consumption of fossil fuels and the resulting waste, mainly greenhouse gases. The "carbon" footprint component is about 52% for EF 1 and the similar "energy land" is 88% for EF 2.[v] According to EF 2, "energy land" is 93% of the North American footprint. A priority on reducing fossil fuel consumption appears justified. The human ecological footprint can be lowered below "1 Earth" only by eliminating the pollution from fossil fuel combustion.

EF analysis uses the capacity of the environment to absorb greenhouse gas emissions, which, as seen in the model shown in Fig. 1, means EF measures "sink" capacity. The real picture is more complex and more disturbing for a couple of reasons. Firstly, fossil fuel extraction is reaching limits sooner than expected. Since we have not been weaning our economy off fossil fuels steadily for the past few decades, rapid energy price inflation will likely make it difficult to maintain the kind of economic vitality and stability needed for a smooth transition to renewable energy alternatives. Secondly, recent evidence suggests that climate change is happening faster than expected. Ice sheet destabilization is one major indicator that the Earth system is more sensitive to greenhouse emissions than most scientists and policy-makers have presumed. Recent articles by Kurt Cobb[vi] and Richard Heinberg[vii] review all these points, and the "Climate Code Red" report[viii] goes into truly excruciating detail so I won't elaborate further here.

The bottom line is that every measure must be taken to rapidly eliminate fossil fuel consumption and dependency in every component of our lives. The key word is "rapidly." Don't passively assume inexpensive alternative energy substitutes will arrive to replace fossil fuels-we may have waited too long to respond to have a smooth transition. Therefore, focus most attention on reducing energy demand rather than substituting a new energy supply. And finally, in the context of ecological economics, fossil fuel depletion and climate change, ask whether what you do in your life, vocation, hobbies, and habits, contributes to the long-term function (or dysfunction) of society.

The U.S. Food System and Fossil Fuels

It would be hard to argue against a claim that a secure and healthy food supply is indispensable to society. A widely known and troubling fact is that the current food system in the U.S. (and most highly industrialized nations) is very dependent upon fossil fuels.

As far as I am aware, the most comprehensive study on the topic of energy use in the U.S. food system is by Heller and Keoleian of the University of Michigan's Center for Sustainable Systems.[ix] The report is from 2000 and makes use of data from the mid-1990s. Although the data are about 10 years old, I don't believe the basic structure and function of the U.S. food system has changed dramatically over the past 10 years. In fact, current trends of increased industrial meat consumption[x] and biofuels[xi], which both rely on grains, make the following case even stronger.

We learn from the study that over 10% of the energy consumption in the U.S. can be attributed to the food system, and that about 20% of this occurs in the agricultural production sector. Home energy consumption (e.g., refrigeration and cooking) consume the largest share at about 30%. Between the farm and the home are everything else (transportation, processing, packaging and retail). Much of this middle portion is a function of the geographic disconnection between production and consumption. Eating food out of season either requires long-distance transportation or energy demanding processing. Both transportation and processing require investments in storage.

Sorting out the proper scale of operations for farms, processing and transportation systems is very difficult, however, because optimization for one factor (e.g., transportation), may be sub-optimal for another (e.g., heat intensive food processing). Within a category, such as transportation, the technologies analyzed may be limited too. A study comparing rail cars, large semi-trucks and small produce trucks may conclude that bigger is better, but what about hyper-local transportation systems using bikes, small electric vehicles and bipedal locomotion? Another complicating issue is that studies may assume the U.S. food system should be more or less similar in its mix of products while lowering energy consumption. For example, tomatoes can be processed using canning or drying. Canning lends itself to centralized operations and so does drying if fossil fuels are used as heat sources. But a naturally decentralized and fossil-fuel free technique such as passive solar dehydration may not even be considered. Large energy savings can be found everywhere in the food system, but especially so if assumptions about scale and consumer-level demand are allowed to change.

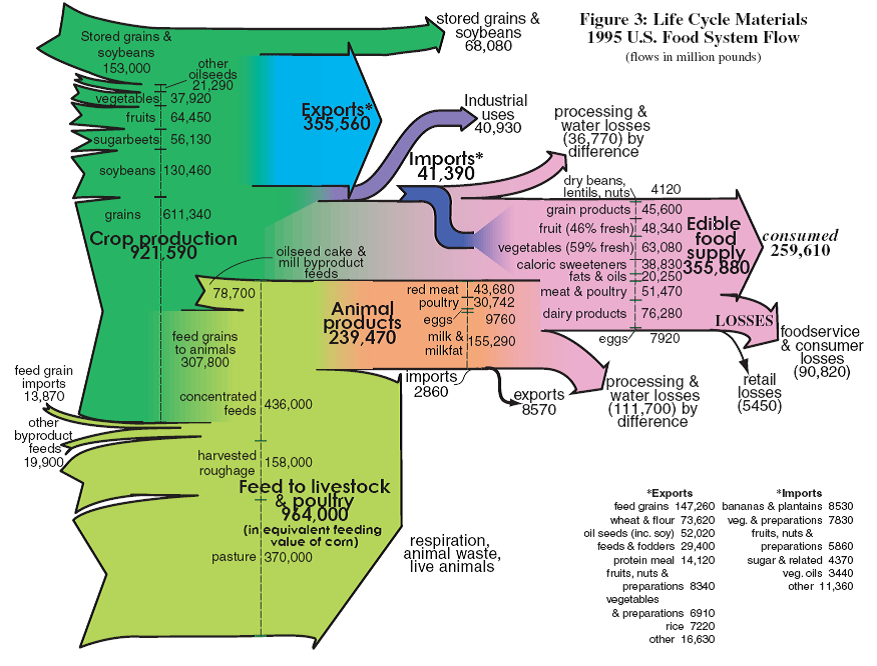

Fig. 3. The energy inputs to the U.S. food system are several times larger than the energy content of the food. A life-cycle analysis identifies how energy consumption is partitioned among economic sectors.[xii]

Another graphic from the Heller and Keoleian report clearly identifies a huge savings potential. Over 50% of U.S. grains are fed to domestic animals, and most export grains go to animal feed as well. Overall, only 26% of U.S. grain production in 1995 went to domestic human consumption.

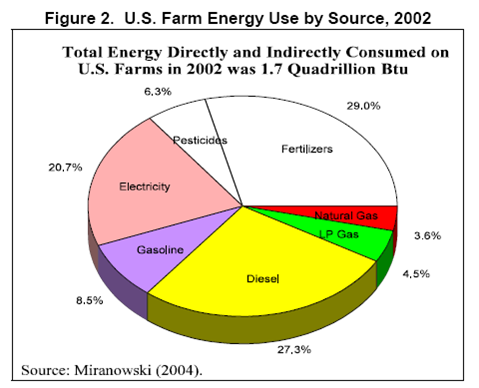

Although poultry need grains, red meat and milk products dominate the feed market and grains are not a natural part of their diets. If red meat and dairy production were reduced to only what harvested hay and pasture could provide, perhaps half of annual U.S. grain production could be eliminated. The acreage out of food production could be used for green manure crops to build soil and fix nitrogen. A 2004 Congressional Research Service report showed that fertilizers are the largest part of farm energy use, and that natural gas to produce nitrogen comprised 75-90% of the fertilizer input (Fig. 5).[xiii] Fixing nitrogen naturally, therefore, saves significant energy. Some of the vast cropland area no longer producing grains could then be used for appropriately scaled biofuels to power farm equipment instead of fossil fuels.

Fig. 4. A reprint of Fig. 3 from the Heller and Keoleian report. (click to enlarge)

Fig. 5. A reprint of Fig. 2 from a 2004 Congressional Research Service report.

An older and less comprehensive on-line review paper[xiv] titled "Energy Use in the U.S. Food System: a summary of existing research and analysis" by John Hendrickson of the Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems, UW-Madison concluded that:

"It appears that some of the greatest saving can be realized by:

- reduced use of petroleum-based fertilizers and fuel on farms,

- a decline in the consumption of highly processed foods, meat, and sugar,

- a reduction in excessive and energy intensive packaging,

- more efficient practices by consumers in shopping and cooking at home,

- and a shift toward the production of some foods (such as fruits and vegetables) closer to their point of consumption."

Hendrickson's paper is helpful in republishing and comparing tables from many previous studies, including "Table 5" reprinted here on the energy consumption of home grown versus market-purchased fruit and vegetables.

Taking Responsibility: Brookside Farm Examples

With this extensive background I introduce the project I have been working on for about two years now, Brookside Farm. This is a 1-acre mini-farm in Willits, CA. It operates as a program of the non-profit corporation North Coast Opportunities, functions as a working farm with a community supported agricultural program serving 15 "shares" per year, exists at an elementary school and is therefore open to classes and tours, and conducts research and demonstrates aspects of a local food system with the collaboration and support of Post Carbon Institute.[xv]

Brookside Farm thinks about food from a "farm to fork" and back again perspective. Farmers create artificial ecosystems, and we therefore look to ecology to guide our practices. Highly productive and stable ecological systems are noted for a diversity of species both in kinds and functional forms. When these diverse species interact effectively, they maximize the rates of productivity and nutrient retention in the system using ambient energy sources. We view ourselves as human members of the farm ecosystem with our labor and wastes as parts of the whole.

To get by on ambient energy as much as possible, we have sought alternatives to fossil fuels in every aspect of the food system we participate in. Table 1 considers each type of work done on the farm, to the fork, and back again and contrasts how fossil fuels are commonly used with the technologies we have applied.

|

Type of Work |

Common Fossil-Fuel Inputs |

Alternatives Implemented |

|

Soil cultivation |

Gasoline or diesel powered rototiller or small tractor |

Glazer hoe, broadfork, adze, rake and human labor |

|

Soil fertility |

In-organic or imported organic fertilizer |

Growing of highly productive, nitrogen and biomass crop (banner fava beans), making aerobic compost piles sufficient to build soil carbon and nitrogen fertility, re-introducing micro-nutrients by importing locally generated food waste and processing in a worm bin, and application of compost teas for microbiology enhancement. |

|

Pest and weed management |

Herbicide and pesticide applications, flame weeder, tractor cultivation |

Companion planting, crop rotation, crop diversity and spatial heterogeneity, beneficial predator attraction through landscape plantings, emphasis on soil and plant health, and manual removal with efficient human-scaled tools |

|

Seed sourcing |

Bulk ordering of a few varieties through centralized seed development and distribution outlets |

Sourcing seeds from local supplier, developing a seed saving and local production and distribution plan using open pollinated varieties |

|

Food distribution |

Produce trucks, refrigeration, long-distance transport, eating out of season |

Produce only sold locally, direct from farm or hauled to local restaurants or grocers using bicycles or electric vehicles, produce grown with year-round consumption in mind with farm delivering large quantities of food in winter months |

|

Storage and processing at production end |

Preparation of food for long distance transport, storage and retailing requiring energy intensive cooling, drying, food grade wax and packaging |

Passive evaporative cooling, solar dehydrating, root cellaring and re-usable storage baskets and bags |

|

Home and institutional storage and cooking |

Natural gas, propane or electric fired stoves and ovens, electric freezers and refrigerators |

Solar ovens, promotion of eating fresh and seasonal foods, home-scale evaporative cooling for summer preservation and "root cellaring" techniques for winter storage |

Table 1. Feeding people requires many kinds of work and all work entails energy. In most farm operations the main energy sources are fossil fuels. By contrast, Brookside Farm uses and develops renewable energy based alternatives.

Our use of food scraps to replace exported fertility also reduces energy by diverting mass from the municipal waste stream. Solid Waste of Willits has a transfer station in town but no local disposal site. Our garbage is trucked to Sonoma County about 100 miles to the south. From there it may be sent to a rail yard and taken several hundred miles away to an out of state land fill. We are also planning to irrigate using an on-site well and a photovoltaic system instead of treated municipal water or diesel-driven pumps.

How much energy does Brookside Farm save?

The complexity of the food system makes it difficult to calculate how much energy Brookside Farm is saving. A research program at UC Davis now devoted to just this sort of question is recently underway, but with few results to share thus far.[xvi]

From previous studies we can find clues about the high energy inputs to fruit and vegetable cultivation. From Fig. 4. above, we can see that fruits and vegetables account for (102,370/921,590) 11% of crop production by weight. Table 3 (given below) of the Congressional Research Service report shows that energy invested in fruit and vegetable production is proportionally higher, accounting for (3759/18364) 20% of the energy for crops at the farm level.

Much of the savings at Brookside Farm occurs off the farm by replacing what would normally be imported, through passive solar preservation and storage techniques, and by shifting consumer habits towards seasonally fresh cuisine proportionally high in vegetables.

Does Brookside Farm Scale? Lawns to Food

Before it was Brookside Farm, it was a field of mostly grass at an elementary school. The school district watered and mowed it (Fig. 6).

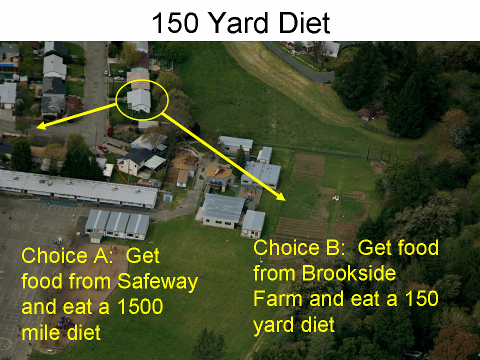

Fig. 6. Brookside Farm in early spring, 2007. The image shows the farm site adjacent to the forest and bordered by grassy fields, school buildings and a residential neighborhood. Arrows from a home contrast distance and direction of food coming from the local Safeway supermarket and Brookside Farm. The 1 acre Brookside Farm occupies about a quarter of the available play field at Brookside Elementary School.

Using satellite imagery, the area of lawn in the United States has recently been estimated:

"Even conservatively," Milesi says, "I estimate there are three times more acres of lawns in the U.S. than irrigated corn." This means lawns-including residential and commercial lawns, golf courses, etc-could be considered the single largest irrigated crop in America in terms of surface area, covering about 128,000 square kilometers in all.[xvii]

The same study identifies where and how much water these lawns require:

That means about 200 gallons of fresh, usually drinking-quality water per person per day would be required to keep up our nation's lawn surface area.

Let me put the area of lawn from this study into a food perspective. The 128,000 square kilometers of lawns is the same as 32 million acres. A generous portion of fruits and vegetables for a person per year is 700 lbs, or about half the total weight of food consumed in a year.[xviii] Modest yields in small farms and gardens would be in the range of about 20,000 lbs per acre.[xix] Even with half the area set aside to grow compost crops each year, simple math reveals that the entire U.S. population could be fed plenty of vegetables and fruits using two thirds of the area currently in lawns.

| Number of people in U.S. | 300,000,000 |

| Pounds of fruits and vegetables per person per year | 700 |

| Yield per acre in pounds | 20,000 |

| People fed per acre in production | 29 |

| Fraction of area set aside for compost crops | 0.5 |

| Compost-adjusted people fed per acre | 14 |

| Number of acres to feed population | 21,000,000 |

| Acres in lawn | 32,000,000 |

| Percent of lawn area needed | 66% |

Labor Compared to Hours of T.V.

For its members Brookside Farm's role is to provide a substantial proportion of their yearly vegetable and fruit needs. Using our farming techniques, we estimate that one person working full time could grow enough produce for ten to twenty people. By contrast, an individual could grow their personal vegetable and fruit needs on a very part-time basis, probably half an hour per day, on average, working an area the size of a small home (700 sq ft in veggies and fruits plus 700 sq ft in cover crops). American's complain that they feel cramped for time and overworked. But is this really true or just a function of addiction to a fast-paced media culture? According to Nielsen Media Research:[xx]

So if we imagine families having the discipline to cut out a single sitcom viewing per day, or one baseball or football game per weekend during the growing season, that would free-up sufficient time to become self-reliant in fruits and vegetables and likely improve overall health.[xxi] (A note of caution though, an article from The Onion warns "that viewing fewer than four hours of television a day severely inhibits a person's ability to ridicule popular culture.")[xxii]The total average time a household watched television during the 2005-2006 television year was 8 hours and 14 minutes per day, a 3-minute increase from the 2004-2005 season and a record high. The average amount of television watched by an individual viewer increased 3 minutes per day to 4 hours and 35 minutes, also a record. (See Table 1.)

Conclusions

For those wanting to contribute to a lower-energy food system, starting with fresh produce makes sense for several reasons:

(1) Significant production is possible in a small area, often what people already have,

(2) Tools and equipment are simple, inexpensive and readily available,

(3) Fruits and vegetables are heavy due to high water content, and therefore energy-intensive to transport and process either by canning or dehydrating,

(4) Growing vegetables and fruits is generally more energy intensive than other crops because of high fertilizer and irrigation inputs,

(5) Quality declines rapidly after harvest, so home or locally available food has higher nutritional value and usually tastes better,

(6) Labor, packaging and storage demands of fruits and vegetables are high in mechanized production systems, making the investment in home-grown produce financially competitive, and

(7) Gardening and small-scale fruit and vegetable farming lend themselves to physical and social activities across generation and income gaps that improve health and enhance a shared sense of purpose and fun.

[i] This graphic was developed based on the principles discussed in Chapter 2 of Daly and Farley "Ecological Economics: Principles and Applications" (2004, Island Press)

[ii] http://www.storyofstuff.com/

[iii] http://www.footprintnetwork.org and http://www.rprogress.org/ecological_footprint/about_ecological_footprint.htm; the original ecological footprint analysis (EF1) is at the first reference, and the second type (EF2) at the second. The major difference between the two is that the second attempts to incorporate aquatic systems (e.g., oceans), total terrestrial productivity, and biodiversity reserves.

[iv] Graphic from: http://www.footprintstandards.org/

[v] For the 50% figure see: http://www.footprintnetwork.org/gfn_sub.php?content=global_footprint; for the greater than 90% and discussion of differences between methods see: http://www.rprogress.org/publications/2006/Footprint%20of%20Nations%202005.pdf

[vi] http://scitizen.com/screens/blogPage/viewBlog/sw_viewBlog.php?idTheme=14&idContribution=1397

[vii] http://globalpublicmedia.com/richard_heinbergs_museletter_big_melt_meets_big_empty

[viii] http://www.climatecodered.net/

[ix] http://css.snre.umich.edu/main.php?control=detail_proj&pr_project_id=29

[x] See especially Table 2. in: http://www.fao.org/docrep/005/AC911E/ac911e05.htm

[xi] http://www.theoildrum.com/node/2431

[xii] Graphic from: http://css.snre.umich.edu/css_doc/CSS01-06.pdf

[xiii] http://www.ncseonline.org/NLE/CRSreports/04nov/RL32677.pdf

[xiv] Although no date appears on this paper, it is clearly related to a 1994 conference and workshop: http://www.cias.wisc.edu/pdf/energyuse.pdf; http://www.cias.wisc.edu/archives/1994/01/01/energy_use_in_the_us_food_system_a_summary_of_existing_research_and_analysis/index.php

[xv] http://www.energyfarms.net/

[xvi] http://asi.ucdavis.edu/conferences/farmtofork/; http://californiaagriculture.ucop.edu/0704OND/editover.html; http://asi.ucdavis.edu/Research/ASI_Program_Proposal_Brief_-_Energy_Life_Cycle_Assessment_in_Food_Systems_9-13.pdf

[xvii] http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Study/Lawn/

[xviii] http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/FoodConsumption/FoodGuideIndex.htm

[xix] An acre is ca. 43,000 sq ft. Our experience at Brookside Farm suggests about 1 lb of produce per square foot of cultivated space is to be expected, with infrastructure and paths requiring significant area. Fruit orchards in Mendocino County yield about 20,000 lbs per acre: http://www.co.mendocino.ca.us/agriculture/pdf/2006%20Crop%20Report.pdf

[xx]http://www.nielsenmedia.com/nc/portal/site/Public/menuitem.55dc65b4a7d5adff3f65936147a062a0/?vgnextoid=4156527aacccd010VgnVCM100000ac0a260aRCRD

[xxi] http://www.csun.edu/science/health/docs/tv&health.html

thank you jason. it is refreshing to read a thoughtful, scholarly post about food production from someone who has both academic and field credentials. may we all exercise self restraint when it comes to expressing ourselves on topics upon which we lack expertise.

My impression is that refrigeration and cooking account for a fairly small chunk of home energy consumption, and that the lion's share is winter heating and summer air conditioning.

In my home, refrigeration represents ~12% of my non-transportation energy costs. It is bigger than my air-conditioning use, but quite a bit smaller than my heating use.

I'm showing the text for the chart of "Type of Work/Common Fossil-Fuel Inputs/Alternatives Implemented" as amputated on its right side. I've got a reallly big monitor, too.

I'll try to change it

Nice one, Jason. On the subject of vegetables being thirstier than normal garden plants, they are. One way to counter this is clay pot irrigation, which has been shown to be at least twice as efficient as other forms of irrigation.

Youtube Video — Path to Freedom - Water Wise Gardening with Clay Pots

The buried clay pot or pitcher method is one of the most efficient traditional systems of irrigation known and is well suited for small farmers in many areas of the world. Buried clay pot irrigation uses buried, unglazed, porous clay pots filled with water to provide controlled irrigation to plants. The water seeps out through the clay wall of the buried clay pot at a rate that is influenced by the plant's water use. This leads to very high efficiency, even better than drip irrigation, and as much as 10 times better than conventional surface irrigation. This method is also very effective in saline soil or when saline irrigation water must be used. It has proved useful for land restoration in very arid environments.

From Buried clay pot irrigation: a little known but very efficient traditional method

Showed the clay pot idea to the Mrs. She said these pots are relatively expensive. The need to be hand thrown and kiln dried which makes their production labor and energy intensive. If you live in an area that needs large amounts of irrigation and can afford to the high price go for it. Here in wet Iowa it may not be worth the investment.

Due to the energy needed to kiln dry the pots the question becomes how durable are these pots? Are these things our grandchildren will inherit or do they need replacement every few years?

Probably the best plan is to scrounge around for used clay pots that would otherwise end up broken and discarded. The hole in the bottom could be plugged with a cork or something, and just about anything flat would work as a lid.

If the thing is left in the soil there's no reason for it to break.

There exist clay pots from the Egyptians and earlier, 4,000 years old. They break when you smash them, they don't erode easily because of conditions. If you stick it in the ground and don't hit with your shovel, then yes they'll still be there for your grandchildren.

I have a concrete backyard, so I use containers, myself - if you're worried about the water, you can use self-watering containers, basically one container with holes in the bottom sitting in another container without, the roots grow down through the holes, the water doesn't evapourate nearly so fast, you can be more irregular in your watering, etc.

The water intensity of vegetables also isn't so much of an issue if you use greywater - water from your laundry, shower and kitchen. A typical household will have 2.6 people here Down Under. A four minute shower daily with a water-saving showerhead, plus various handwashing through the day, that's 45lt daily each, or 117lt for the three. Each load of washing will be 50-150lt, depending on the machine - call it 100lt, and assume a reasonable two loads a week, for 200lt weekly, 29lt daily. Dishes done by hand in the sink daily will be 10-20lt, another 15lt a day. In all that greywater is 161lt daily.

A typical suburban house might be on a 600-800m2 lot, with 220m2 for the house, 150m2 for car space, driveway, and difficult-to-use space along the edges of the lot. This leaves 230-430m2 for garden. Given that most will want plenty of pathways, and maybe a little spot for an outside table or shed, allow just half for actual garden beds or containers, 115-215m2.

Take your 161lt of greywater on that 115-215m2, and essentially you're talking about 1lt/m2. That's plenty except on dry 30C or more days; with lower temperatures or higher humidity, no worries.

You must then use low-salt detergents, but that's not a bad thing.

Feeding recycled greywater into these pots would work a treat. Excellent method.

Thanks for the tip on the clay pot irrigation. Are the cheap orange clay pots sold in the US the proper "unglazed porous" material?

Good article Jason! You mentioned some soil cultivation tools in the "Taking Responsibility" section that I can supply some details on. Tools are my area of expertise!

For soil cultivation you suggested the following hand tools:

The correct spelling is Glaser Hoe - It is a also called a wheel hoe. Very nice intermediate scale tool to use when planting crops in rows. Picture a rototiller shaped machine with no engine but a large wheelbarrow-style tire out front and tines or a blade behind the the wheel that you push through the soil. See these links for more info on the Glaser Hoe and how to use the wheel hoe (about a third of the way down the page)

The Broadfork is also often called a U-Bar. It is used to loosen and aereate existing garden soil. (do not use it in sod!) It consists of five or so metal tines, approximately eight inches long, spaced a few inches apart on a horizontal bar, with two handles extending upwards to chest or shoulder level, forming a large U-shape. See these links for more info on the Broadfork or U-Bar and how to use it (about a quarter of the way down the page)

The third tool Jason listed was an adze. But an adze is used for woodworking to smooth rough-cut wood (think log cabins). On a farm or in a garden the tool that is often mistakenly called and adze is actually a Mattock or Grub Hoe. It consists of a heavy-duty sharp steel blade set almost perpendicular to a long wood handle. It used to chop into the soil or sod to make new gardens or loosen existing ones. This tool can do everything a rototiller does. See these links for more info on the Mattock and Grub Hoe and how to use them (a grub hoe is called an Azada in the UK)

In honor of full disclosure, the site EasyDigging.com linked to above for the mattock and grub hoe is my site. It is a business created to be viable and useful in a world decreasing fossil fuels and an increasing focus on local, small-scale agriculture.

Greg in MO

Thanks for the feedback! I have wondered about the dual use of an adze, knowing it is originally designed for wood work for a while now. In the local farm supply store adze's are sold as cultivating tools. In Lehman's I saw an Italian grape hoe that looked very similar. I have used a "cutter Mattock" myself, but this is more for brush and stump removal than soil cultivation. I will check out your site.

Another place manufacturing a low wheel cultivator is Valley Oak Tool Company:

http://valleyoaktool.com/

We have busted our Glaser hoe repeatedly but the first year included a lot of sod removal work (best left to an "adze" like hoe). A local welder has helped us repair and upgrade our Glaser hoe very cheaply and simply and we hope this keeps it functioning longer.

He is also working with us to improve the durability of the broadfork/U-bar, which has also broken many times. We will report on these on our web site: www.energyfarms.net

I used my azada today to prep a 6ft X 25ft bed to plant spinach. It made fast work of the job, I got the whole bed tilled by hand in about 90 minutes, and I'm an old out-of-shape guy that has to take frequent rest breaks - a young fit guy could have probably done the job in less than an hour. The azada is a powerful, versatile tool. My understanding is that there are many people in the third world that pretty much subsist just with this tool.

Hi WNC Observer,

Please send me a message off-list at "contact at easydigging dot com" about your azada tool.

Greg in MO

I have tried something similar -- with plastic jugs -- any gallon or bigger jug that I have anyway. I dig them in and punch about 3 large needle holes in them. Anything bigger and the water runs out much to quickly. Probably not quite as effective as a clay pot -- but certainly cheaper.

Some Garden supply outlets sell carrot shaped items with holes in them which you put sand in and put into the groud with a 2 liter bottle for the water. I find the jugs work better, more capacity and cheaper.

the material should be porous overall. clay pots are expensive in the US? here you can have your own mini ‘fridge’ for 20 dollars, and if you have a cellar you don’t need it, or if you live at or above, 1,000 meters. (from Switzerland.)

Clay pots are not (currently) expensive in the US. I think the comment was aimed at some notion of "scalability". In other words, you wouldn't want to try to irrigate a 100-hectare field with them. And fired pottery has been made with fossil fuel for a century or two: is there a way to fire pottery with solar heat? (wood was burned for this application before 1850)

But for a little urban gardenspace, like mine, it looks like an excellent idea. Especially here in Texas and other such semi-arid climates. You never know when it's going to rain again (though the climate seems to have been getting wetter -- AGW? I dunno) and the clay pots would be an easy way to be frugal, yet keep your roots moist.

Some of the decorative pots they sell at Marshall Pottery are glazed with lead, however. They are clearly marked "not foodsafe". You definitely want unglazed terra cotta for this application.

Jason---

I'm still munching dried apples and asian pears from a friends farm on Sherwood Rd.

He begged me to bring the truck up and take all I could, as he had a huge surplus.

It took months to dehydrate all this.

It was funny- I had trouble giving asia pears away- the sheeple would rather pay $3.00 a pound for them at Whole Foods.

The only thing my friend buys is cooking oil, tortillas, and cheese. The rest he pretty much produces himself.

Olive trees have been planed as a oil strategy.

Hi neighbor! Please introduce yourself to me sometime. I'll be at Brookside much of the upcoming season.

Do you have a solar dehydrator? Do you know about the local group called "The Grateful Gleaners"?

The gleaners harvested over 6 tons of fruits last year (which was a record fruit year in Mendocino County) and the big problem was preservation. This led to a flurry of interest in passive solar dehydration. Three dehydrators were made last year in response to be deployed this year. We are always looking for those with experience to help us build and use the finest equipment.

I'm not sure about net energy use of this method, but I use the Alton Brown "McGuyver" dehydrator: Paper furnace filters bungeed to a box fan. Dehydrators that depend on heat actually partially cook the food, changing its flavor and nutritional profile. I have dried everything from herbs to jerky this way and, at least culinarily, the method is fantastic. I reuse the filters for everything except meat. In theory I could reuse it after meat because they are too dry for bacteria, but I just can't bring myself to reuse something I can't wash that has come in contact with raw meat. Any microbiologists here who can tell me if I'm being too paranoid?

I'd be interested to know more about solar dehydration. I've gained the vague impression that it's a bit hit and miss. Are you finding that it works as well as an active drier?

Peter (in the UK, where I guess passive solar woiuld face greater challenges).

We are going to check out this design, which was tested at a university in southeastern U.S. Our summers are dry and sunny, so performance should be even better.

http://www.tuffydog.com/solardryer.html

Can dry about 5 lbs per day, per dryer. Be good to scale this up substantially or deploy a miniature fleet. Two of these dryers working for 100 days can dry 1000 lbs.

Jason--

I used a electric dehydrator. I would like to migrate to solar--

I have dried tomatoes with solar- with success. It was a good year for fruit in Mendo.

I lived out on the coast at Pt Arena, but costal fog was a liability there.

I will stop by Brookside.

Thank you Nate for a very interesting post. It would be interesting to compare the data about the inputs for Willits versus other areas of the continent. I am building a passive solar home on some marginal agricultural land overlooking a lake at latitude 53 north. I hope to have a small garden and greenhouse to provide a good portion of my fruits and vegetables.

I just had to click on the Onion link. Thanks for the chuckle.

This is a useful article, Jason. The information in it needs to be distributed widely especially on the East Coast.

I agree with the demand focus. Regarding demand, the other side of the equation for reducing overall ecological footprint of our species is population control. Humans are the one species that has the ability to humanely limit its population growth. Therefore the women's reproductive rights movement and the right to dignified death movements ought to be supported by our public policies.

Thanks for the excellent contribution Dr. Bradford. One question: I know it is probably beyond the scope of your article, but do ecological economists ever try to deal with the twin issues of economic and population growth? You seem to have assiduously avoided any discussion of that, yet I don't see how the human sub-system can function properly as a part of the greater Earth system without surrendering the concept of economic growth and without making conscious decisions and plans to control the size of its population (rather like what China has been doing since (roughly) 1980).

Ecological economists deal squarely with these issues. Some good books to read might be Herman Daly's "Beyond Growth," or Richard Douthwaite's "The Growth Illusion."

I liked your post Jason and the improved understanding of the energy profile. You make a strong case for growing as much of our own food as possible and show how this translates into massive energy savings. I suspect you could elaborate on the energy savings conferred by the improved health from eating quality food ( a future post? :) ).

Those that would advocate that there are too many people on the planet never seem to want to talk about the fact that we have never been in the position where there were too many people, but rather too many that want to (intentionally or unintentionally) make poor choices. It's not the number its the choices made.

You've just illustrated how a different growth model can procure more than enough food in a sustainable manner weather permitting.

Agriculture can, if we so choose, be a vehicle for sequestering massive amounts of C02. What other group can make such a claim? So instead of being 10-20% of the problem a different model such as you propose can be part of the solution.

From addressing slaves in our food supply to not polluting and depleting the aquifers or causing degenerative diseases and providing habitat for wildlife etc etc. The number of issues that boil down to agriculture choices are legion.

When oil production dips, the price of oil will skyrocket, the stock market will really crash, inflation will go wild, people will not be able to sell their houses, and therefore they will not be able to relocate to sustainable areas. There will be no mass move from the cities and suburbs to rural areas, as some Peak Oilers have indicated. Sad, but true. I'm glad that I relocated. Hope you will join me, before it's too late.

What a fantastic story! I haven't logged in to the oil drum in months. I had been planning to write a diary at Daily Kos about this (at a much more superficial level). Over the years I've been writing a series title "Kermit Wrong: It IS Easy Being Green" and one of the recurring themes has been CSAs.

I've been very busy for the last six months trying to get my business going and still pay my mortgage and such, so I haven't participated there or here for some time.

The diary will be about an individual operation of the what you here put in a global perspective. My CSA just sent their subscription newsletter and a share of the harvest this year costs exactly what it did last year. In my diary on That Other Site I will talk about why CSAs are better, but this time I plan to play up the economic angle; the inflation fighting angle.

I'm not a vegan or a vegetarian, but I'm also going to talk about how my purchase of 1/4 of beef from a local grass-fed beef producer is also going to be about the same price this year when all other food is going up, up, up.

Finally, I plan to mention that I lost 9 pounds over the last year and the reason is almost certainly the four to five months a year I spend putting mostly whole, fresh, organically grown produce in my face instead of mass-market burger crap.

It is absolutely fascinating to me to see such a well written survey of the macro-scale of this issue! Thank you so much for this!

Thanks for your kind words and am so glad to hear from another CSA farmer!

A really amazing film on the development of a CSA is "The Real Dirt on Farmer John."

Oops! I'm NOT a CSA farmer, I'm a CSA customer. But I plan to bring the clay pot irrigation idea to my friends at my CSA!

I'm aware of the the movie you mention, but I haven't yet seen it. I will make sure I do...

If I were to recommend one book for urban and suburban people interested in home energy efficiency and home food production it would be The Integral Urban House by the Faralones Institute, 1979, ISBN 0-87156-213-8. The most likely source is Powells bookstore, http://www.powells.com

It covers everything from alternative energy, to grey water, to home food production and everything in between. I might add that things are presented in reasonable detail so it's not just a general overview.

My personal feeling is that some version of hydroponics/aquaponics makes the most sense for most people. Although somewhat capital expensive* in the beginning, it offers the most energy efficient growing with the (potentially) highest yields. I grew a significant amount of produce hydroponicly using organic nutrients years ago and am trying some new vertical systems this year in addition to my continuing work on terra preta.

Todd

*The system I'm trying this year is dirt cheap. It'll use used gallon water jugs hung upside down with the bottoms cut off. The jugs will be wired to a "T" post.

My experience with gallon jugs is that they become brittle and disintegrate over time. Even when kept in the dark. I know this because I'm a pack rat.

That said, you might hang onto the little screw-on caps for an easy method of varying the size of drip hole. You can easily experiment by changing the caps around.

This is a great post. It very sensibly differentiates between the crops that are more amenable to localization and small scale production and those that are not. I hope that somewhere there is a wheat or soybean farmer out there reading TOD who can enlighten us as to what can and can't be done to reduce fossil fuel use in these operations.

"Even with half the area set aside to grow compost crops each year, simple math reveals that the entire U.S. population could be fed plenty of vegetables and fruits using two thirds of the area currently in lawns."

Excellent post! The point you make about lawns is why I think the burbs will not go away but will certainly be radically transformed.

An African or south Asian rural villager would love to have a 1/4 acre suburban lawn to work with.

Of course all the bluegrass and fescue would disappear to the goats and chickens.

Have the kids take the cow down to the abandoned soccer field to graze a little this morning.

I used to live in the old core of a small town in the East and in all the back yards you could figure out where the garden, the chicken coop and the privy had been by the quality of the soil. That was on the small lots. The larger ones had sheds for cows and horses.

The worst thing about surburban development is the soil destruction but that can be slowly repaired.

And internal combustion engines will not go away until the very last drop of FF is used.

It should be one big chaotic mix.

I would like to hear from those folks too! Been experimenting with small grains (wheat, barley, rye) on small scale, such as what can be done with hand equipment. Scaling up grains beyond the simple tools gets expensive quickly. Cleaning the seed to the level most people would accept is a challenge without really fine screening sets and shaker tables or specialized field combines.

However, small plots of grains (e.g., 1-5 acres) can be done by hand inexpensively (though still require some mechanized tillage if labor inputs are to be kept low) and if the feed is going for poultry a simple threshing will suffice. Given current prices of grains and straw small poultry operations may consider this.

Have you considered rabbits? Rabbits eat lots of different kinds of weeds and grasses that may grow around the perimter of a cultivated field. (you may need to cut these grasses and give to the rabbits or you could put the rabbit cage out on the grasses but they are good at tunneling out.) You can use rabbit manure as fertilizer. Rabbit droppings are a perfect medium for sprouting seeds. Our rabbits eat surprisingly little grass yet produce a lot of manure....We're not ready for goats and horses or cows (maybe one day) so in the meantime rabbits are a way to help us through this transitional time as oil goes from surplus to shortage,

We have thought about rabbits but I dislike how they are so confined in cages because of their escape artist ways. Any ways folks have to use rabbits in a "chicken tractor"-like manner would be useful to know about. Perhaps a mobile, bottomless cage that is designed to be difficult to dig under?

The rabbit tractor has been tried, it didn't work... but it led to the invention of the chicken tractor:

from You Can Farm: The Entrepreneur's Guide to Start & Succeed in a Farming Enterprise by Joel Salatin.

Jason, thanks for the excellent article. It's very timely, as I've been thinking along these same lines for myself and having long discussions with my wife trying to convince her it's all a good idea.

I want to hear more about grain farming. "Man does not live by

breadvegetables and fruit alone". The literature I've seen on organic gardening, permaculture, and small scale farming seems to emphasize vegetables and fruit. I guess because to make money at grain farming you need big scale and that means tens of acres and tractors and combines, and it just can't be done as economically as industrial farming can do now. But seems to me it would be good to prepare for the day when the industrial grain farming model becomes uneconomic due to energy costs (not to mention all it's other problems).To me, the direction you outline is the only solution that makes sense. Trying to develop enough alternative energy to keep the whole consumer-urban-suburban-auto culture going in its present form is madness.

Wow. What a story. Thanks for the tips on the rabbit tractor. Confirms my suspicions and not surprised people have attempted in the past.

A rabbit tractor/lawn mower can be made out of 3 old bicycle wheels without tires and a role of chicken wire. It is a cylinder shape, 2 wheels make the rabbit proof ends with another one in the middle for strength and stability. Make 2 trap doors in the chicken wire to get them in and out. Two rabbits in each end and off they go, rolling it forward over the lawn as they reach forward to get the grass ahead of them leaving little pills of fertiliser in their wake.

Grain farming may be one of the few large scale industrial agriculture models we actually hang onto in the future as the energy content from grains is so much greater than fruit and veg, stores indefinietly and can be cooked into a variety of differnt foods.

Grain has been cultivated and harvested for thousands of years and there is every reason to suspect it will continue into the future, albeit with tools other than gigantic oversize tractors and combine harvesters. There is also the possibility that bio-diesel could be directed exclusively to grain production and distribution.

Production yields of grain may drop without FF fertiliser inputs, but our knowledge of crop rotations along with advances in GM technology may mean that we can still grow enough grain to feed everyone an adeqaute amount of daily bread. Donuts, bagels, cookies, cakes, biscuits, and all the other crap we currently stuff into our overfed selves will proabably have to go. That won't do most of us in the West any harm at all and could go a long way to improving our health.

Nice work JB.

At the heart of this debate (and others) is the viability/wisdom of responding to peak oil with a one-size-fits-all answer key. Personally, I think the responses to Peak Oil will be bi-modal, on many different scales. The more nucleii of local food production (for the people interested and able to do so), the less strain it puts on the just-in-time structure of the rest of the food system. Its the Homer-Dixon argument of redundancy and resilience over efficiency. I also believe (for some, if not many), this type of plan makes one healthier and happier than spending time and resources on things that are just spinning of societal novelty wheels. To actually produce some basic goods, while creating social capital and skillsets at the same time seems like a no-brainer. It also reduces the planning and systems load on regional/national transportation infrastructure.

But I guess like many other aspects of the Peak Oil problem, those that 'like' to grow some of their own food, or would like to learn about it, 'see' your post as one of the silver bullets that is worthwhile pursuing and devoting time and resources to. Those who 'dislike' gardening or live in cities with no land themselves probably 'see' the logic of continued expansion of industrial agriculture, even for veggies and fruits. It's very difficult to approach a post such as yours without ones own predispositions!!

In any case, I am predisposed to agree with your conclusions...;-)

(Just got my grain mill in the mail today - the kind I can hook up to an exercise bike)

do you have a link for that grain mill

Link to grain mill. This one was more expensive than the ones at Lehmans and other places but came with spare parts and can be attached to a bike or motor drive.

(Just got my grain mill in the mail today - the kind I can hook up to an exercise bike)

http://www.csbellco.com/ The No 60 has 3 plates course, med and fine. Course does a fine job of making rock dust.

Hints:

1) Human bike power is uneven. If one can add a flywheel mass that can 'smooth' things out - only if the hands control the grain rate.

2) You should consider a screen at an incline to pass the milled bits over to do the separation of flour from non flour. You can re-mill/re-sift, feed the 'non-flour' to a brewing process or to 'wireworms' (aka mealworms/beetle larve) for you r insect protein.

3) Rather than direct drive - run the bike gear to a mount to absorb the non-rotational forces so a transmission shaft 'only' transmits rotation.

While such might be a 'fun' project - you might wanna just buy a motor for the mill and enough solar panels to cover the motor - that way you are the 'local miller' in the post-oil-appocolpise! For the excersie - just put a generator on the bike and feed into a battery-DC system or air compressor (gets harder to pedal over time then you get 10 sec-5 mins of tool use depending on air tool). If ultra-caps ever happen - you can consider that. Or you could just buy a Kitchen-Aid Mixmaster and their grain grinder. Said grinder works too.

Remember: As you pedal, you are adding wear to your own joints.

(if anyone cares I can send pictures of my CS Bell No 60 hooked to a bike frame)

The emphasis in the above quote is mine. In spite of its promising beginning this post devolves (as is usual on TOD) into a discussion of techniques of economic production. It’s not that I find such discussion uninteresting or valueless. Quite the contrary. I highly appreciate the work that you and others are doing to develop sustainable methods of food production. Such work may well be the most valuable practical development work that can be done at the present time. Nevertheless, the discussion of economic technique neglects the equally important (if not more so) discussion of the institutional reform necessary to allow the formation and pursuit of intelligent economic goals (as opposed to our current economic goal of growing the total volume of economic transaction as rapidly as possible). Your suggestion that we need to reduce consumption and moderate our desires with respect to material wealth is of course correct, but there must be a profound social and political transformation if reduction of consumption is to lead to some other end than a gigantic recession. If the desire of money to make money continues to be the driving force of manufacturing infrastructure investment, mere reduction of scale cannot solve our problems.

Every time I try to make this point I seem to be dismissed as some kind of left-wing dinosaur who is attempting to revive some musty, antiquated, 19’th century philosphical debate which was long ago decided for all time and about which nothing new can be thought or said. Instead of reiterating general points which I have made previously let me illustrate my ideas about the need for new economic institutions by a concrete example. I will discuss a society supported by draft animal powered farming. I choose this example not because I am predicting that this is the farming system we are headed towards, but because I want to choose an example of a relatively simple form of economic production without a complicated chain of intermediate suppliers.

Suppose then that farmer A farms with horses as his motive power. He raises his own horses so that they are an output of his land and labor. He raises a few more horses than he needs for his own work and occasionally sells one for some extra income. His neighbor, farmer B is a competent farmer with a track record of successful, profitable farming. However, he has had a run of bad luck with crops partially destroyed by bad weather, pests, etc. and has fallen on relatively hard times. Now one of farmer B’s horses breaks a leg and he has insufficient draft animals to bring in his crop. He goes to farmer A and says, “As you know I have been having some bad luck for the last year or two. And now I have lost one of my horses. I wonder if you could give me horse so I can bring in my crop. I will pay you for it after I bring my crop in.

Farmer B says, “I know you are a good farmer, and I want to help you out. However, if I give you a horse without payment I am taking a risk since the horse might break a leg or you may not be able to get enough income from your crop to pay me back. In order to compensate me for this risk I am going to have to ask you to pay me more than the market value of the horse after you get your crop in.”

The investment which farmer A is making a is wealth preserving investment. If farmer B gets the horse he will be able to produce the same crop that he always produces. Society does not get richer as a result of this investment but is prevented from becoming poorer. In such a case charging interest is a transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich or from the unlucky to the lucky. Furthemore if farmer B is a compentent farmer who is merely having bad luck the need to pay interest increases the likelyhood that he will go bankrupt, which would be a bad outcome for the community.

On the other hand suppose farmer B comes to farmer A and says, “I have an idea for a new cropping scheme which will increase my output by 30%. However, I need an extra horse in order to carry it out. I do not have enough ready cash to buy one right now. If you give me a horse I will pay you for it after I bring in my crop.” This is an example of an investment which increases society’s wealth. In this case farmer B can pay farmer A interest and if his new cropping scheme works then the whole community benefits. We currently have an economic system which assumes that all investments are wealth increasing investments. If we reach a point where we need to maintain wealth rather than increase it then this system is going to function very poorly.

So what is the alternative? In spite of the unfairness of charging interest in the first case presented, farmer A’s desire to be compensated for his risk is very understandable. Even though he knows that farmer B is competent and that it is desirable from a community point of view that he should be able to harvest his complete crop, he may still not wish to accept the risk. However, the risk could be shared by the whole community. If a community bank existed which had reserves funded by tax money, then farmer B could go to the bank and ask for an interest free loan. The banker (who is paid a salary as public servant) knowing that farmer B is competent and that the community will benefit if he brings in his crop will loan him the money. Farmer B then buys a horse from farmer A who receives a fair price and not more than he deserves just because his neighbor has had bad luck. And the risk of the undesirable outcome of bankruptcy for farmer B has been reduced.

Note that in such a system of community investment no barrier exists to making wealth increasing investments if they are available. Farmer B could go the community bank with his scheme for increasing his crop yield and get a loan (still interest free). If his scheme suceeds and he permanently increases the output of his farm then the bank will receive interest indirectly in the form of increased taxes.

This example is the kernel of an idea which I call community investment capitalism which would eliminate private finance but preserve private enterprise.

or, farmer A could not only loan farmer B his horse but also help him plant. he is paid back with a thank you, and he has a stronger neighbor.

I agree with you and this would be a great topic for a whole other post.

For some background, the CSA movement has much to do with circumventing the current system of finance and profit-driven ownership models.

For some additional background I would recommend:

http://www.feasta.org/

http://globalpublicmedia.com/richard_douthwaite_on_the_reality_report

http://www.feasta.org/documents/shortcircuit/contents.html

Jeeze, Louise....it is still BAU. It doesn't matter that there is no interest via a community bank. Two of us posted the same link yesterday to Jeff Vail's site. It's dinner time so I can't expand this. Read Jeff's essay... http://www.jeffvail.net/2008/hierarchy-must-grow-and-is-therefore.html

Todd

The correct link is

http://www.jeffvail.net/2008/02/hierarchy-must-grow-and-is-therefore.html

You left out a node in that link:

http://www.jeffvail.net/2008/02/hierarchy-must-grow-and-is-therefore.html

Moderator, you can edit the link into the parent post and delete this one if you wish.

And a comment on Jeff's essay: Darwin selects for growth. While there are a variety of strategies for this, from the "blue whale" strategy (one offspring every X years) to the "marine invertebrate" strategy (spew larvae at high tide), the individual that replicates wins. Which makes me a loser, more or less, I guess...

Not really, the individual dies. Who actually wins is a random subset of the individual's genes (those that end up propagated into the offspring).

This is obviously a semi-serious remark but it contains a common fallacy I think is worth pointing out. In discussing evolution, people often forget that while our genes have a stake in our replication, we have no stake in theirs (it can't prevent us from dying and once we're dead we don't care).

This is petty much the system we have now! The bank assumes the risk and it has to pay the salary of the bankers so it must charge interest. This is no different than going down to the local farmers co-operative and booking up on credit all the farm inputs you need. No interest is charged. Both are types of credit and there is a need to differentiate between high risk and low risk - unsecured and secured.

Your suggested community bank funded by compulsory confiscation of private profit to be invested in risky enterprise that are dispensed by a public servant introduces a political element. The bankers then must be elected so they can represent the investors/taxpayers. The American decalaration of independence was founded on the priniple of no taxation without representation.

Many banks today provide credit to businesses to keep them afloat during tough times, ot with the intention of the business expanding but simply not dying. Bnakers have to make these judgements every day about what is a good investment and what is simply throwing good money after bad. Sometimes it is better to let people go bankrupt and end the misery than to keep funding a losing enterprise but thi has to be left to the market rather than an elected or even worse unelected official.

I don't see why you think cahrging interest is unfair if it is applied universally. Risk has to be priced. It prevents stupid ideas and lazy people being funded with hard earned community wealth.

I agree with Jason below that this issue should be dealth with in another post. Why don't you write it up and get it posted fo general discussion.

JB,

Great post and thank you for the work you do, both on the ground and "in the air", if I can refer to the media that way. I saw the story on your farm on Peak Moment TV and see that you have a couple of other conversations there as well. I'll check those out later. I lived in Santa Rosa for a number of years and came to Solar Expos in Ukiah in the mid 90's, met John Jeavons, bought seeds from Ecology Action. I someday want to take a pilgrimage to the Real Goods Automobile graveyard / garden, if that is still in existence. In any case, Willits is quite the center of NoCal green thinking- thanks.

I too am of the opinion that the Suburban Lawn is the great green frontier. David Holmgren has many important things to say about that, as well. I remember reading in the Permaculture Designer's Manual that the energy investment in the US lawn makes it one of the largest agricultures in the world, larger than India's (at the time- late 1980's)in terms of energy impact, and produced as close to nothing as possible- I guess it serves to retain and maybe even build a little soil.

I'm in process of converting my village 1/3 acre to a Permaculture design. Planted apples, pears and a peach last year. This year I'm going for blueberries, paw paw, jujube, persimmon and hardy kiwi, and perhaps a trifoliate orange (bitter lemon). This along with the usual greens, herbs, potatoes, veggies and flowers. I'm aiming to turn this into a demonstration garden. I also work with a couple of community garden projects in Rochester, including Rochester Roots. I blog at greenerminds.com on sustainability issues here in Western New York.

Years ago I read somewhere that 90% of everything sold in the supermarket comes from just 16 species of plants and animals. This brought up the idea of using hydroponics to grow the plants and animal feed as part of an integrated food production and distribution system. By staggering production schedules the need for long term storage is eliminated as well as long distance shipping. It is the ultimate in industrial agriculture and may be the only way to grow enough food for 10 billion people in a world suffering from adverse climate change.

1) In 1995 the four largest supermarket chains controlled 1/4 of all food sales; by 2000 the proportion was half.

2) Because of additional packaging, transport and overhead, a purchase from a supermarket produces 17 times more CO2 than from a farmer's market.

3) Every year we lose 5% of our livestock varieties and 2% of our agricultural varieties. Probably for production reasons. For example, east coast US used to get "savoy" style spinach, but now gets the smooth leaf stuff. From the West Coast. Smooth leaf is easier to process too.

1 and 2 from NW Earth Institute CO2 study guide. 3 from from Master Gardener program at UMaine. Centralized food requires a bigger hierarchy, more processing, fewer species and far more fossil energy. Taken together, all of the above suggest to me a large increase in energy use over the past decade in the US food system.

We're pouring energy into our industrial ag system to decrease entropy and to eliminate diversity and resilience in favor of efficiency.

We will not cooperate. Increasing our own "fitness" as a species requires that we crash and burn. Those who can afford to waste energy - those with Humvees, those with big peacock tail feathers and the biggest of all diamond jewelry, those who can start wars to trash the resources of others - those will harbor the winning genes. Unless their antlers get too big and they die. This is going to be an evolutionary moment.

What is a wedding ring but a symbol of wealth and power? What is one supposed to spend on it? I remember seeing that somewhere years ago. Deliberate, conspicuous consumption wasted. [I had a good laugh over that tonight with a friend who pointed out that it was a very good investment for him.]

I'd not expect shortages of energy or resources to change that. What will be more impressive and suggestive of a survival edge than profligate waste?

What is liberal economics but the cultural sanctioning of the maximization of that greed and waste at the individual biological level as fullfilling the greater collective goals of society? No, our cultural institutions are not going to be very helpful. On the other hand, my guess is that they are so far askew already that it will take little to reduce them to irrelevance [many will argue they are just about there already]. These institutions will be used to cause an immense amount of damage - probably the maximum amount of damage that society can bear - because otherwise society will not re form.

Hope is one's expectation of the future. If we are at 1.5 or 2 earths overdrawn, then what are the scenarios for which we might have hope? False hope is presumptuous.

cfm in Gray, ME

Actually, the wedding ring's not the expensive part, it's the engagement ring.

On proposing, the man shows his suitability as a husband by his ability to offer conspicuous waste. "I'm so wealthy, I can waste. So imagine what I can provide in the way of useful stuff!"

As a city boy who grew up playing Nintendo, I have tried my hand at cultivating my lawn to grow food at home. The verdict?

Starvation, until I found some Permaculture friends. The challenging variables:

MOTIVATION:

People's willingness to try and supplement their diet with home grown goodies

TIME:

People are starved for time, and exhausted from their corporate slavery to truly put in the effort it takes. Solution: Get some friends and make it fun!

SPACE:

Very little yards these days in America. Every inch of soil should be considered.

KNOWLEDGE:

I was clueless. Even with a now extensive library of books, nothing beats hands-on teaching from farmers.

WIVES:

Mine, anyway. She would rather us subscribe to a CSA and support those who know how to grow food already!

Solution: We subscribed to a CSA and I will keep trying to grow as much as possible while encouraging others in the neighborhood to do the same

www.lawnstogardens.com

"Farmers create artificial ecosystems, and we therefore look to ecology to guide our practices."

An otherwise excellent article, but unfortunately that single sentence means I must add my voice to the opinion that you still don't get it. The assumption that farmers are in the business of "creating artificial ecosystems" is the very reason that we are in the mess created by unsustainable industrial agriculture in the first place. Some would even argue that modern humans were doomed from the very beginning of "artificial ecosystem creation", also known as agriculture, as much as ten thousand years ago.

When the explicit assumption stated above, and that sentence speaks for a very large number of people, is changed to "Farmers work within existing ecosystems, and therefore look to them to guide their practices", only then will humanity have a shred of hope for attaining true sustainability. It's not a new idea, I recommend the various works by Masanobu Fukuoka for further reading:

http://fukuokafarmingol.info/fover.html

Speaking of reading, It's odd that an article with the words "Ecological Economics" prominently displayed in the title makes no mention whatsoever of one of the better texts on the subject, which is freely available at the Encyclopedia of Earth:

An_Introduction_to_Ecological_Economics_(e-book)

Authored by Robert Costanza, professor and director of the Gund Institute for Ecological Economics at the University of Vermont, and co-founder of the International Society for Ecological Economics. He spoke on the subject in Seattle recently, audio recordings of which have also graciously been made freely available:

http://washington.chenw.org/lectures.html

Cheers,

Jerry

Part of me wants to argue that you are nitpicking on semantic details...but I don't want to downplay too strongly the importance of word choice.

In a sense I see this issue as both "working within existing ecosystems" especially at the landscape scale, and "creating artificial ecosystems." After all, if a fence wasn't built on our farm the deer would eat the food each night. While trying to keep the deer out, we are also providing a lot of space for beneficial native insect species and birds through design of plantings.

Perhaps you are correct that in the long-run we can only exist sustainably by tossing agriculture aside and going back to hunter-gatherer/small-scale horticulture ways.

Thanks for the references to the older Costanza et al textbook. I look forward to the proposed second edition. Costanza is at the same institution as Joshua Farley, who I interviewed here:

http://globalpublicmedia.com/ecological_economics_on_the_reality_report

and I believe both Costanza and Farley may be on Nate Hagen's thesis committee.

Jason

Outstanding post

This year I'm going to be planting a double row of sunflowers 4' inside my fence line hoping that it will act as a double fence, a common solution for dear. I'm still searching for a small scale oil press. Not the press from thejourneytoforever and I've seen some of the presses from china and india, they don't seem to be a good investment to me. any thoughts

"Part of me wants to argue that you are nitpicking on semantic details"

Anyone who reads, and understands, the Fukuoka material will clearly see that the two viewpoints are actually worlds apart.

"Perhaps you are correct that in the long-run we can only exist sustainably by tossing agriculture aside and going back to hunter-gatherer/small-scale horticulture ways."

Just for the record, that's not what I said. Not even close. Don't get me wrong, I can easily see why you might jump to those conclusions, however those are NOT my conclusions as your statement seems to erroneously indicate.

Cheers,

Jerry

... that would seem to be the signpost leading toward that reading.

But, of course, labelling all agriculture a 'artificial ecosystem creation' ... even if its "some" doing so ... itself interferes with raising the prospect for the husbandry view of agriculture, that agriculture can only be sustainable when it is a working partnership with other participants in natural ecosystems.

Since the most critical point to bring into focus is not whether its artificial or natural, but whether its sustainable or unsustainable. If all efforts to create an artificial ecosystems (though the full-fledged concept boggles the mind) are doomed to being unsustainable, then filtering out the unsustainable will take the artificial with it.

I propose that there are two criteria for agriculture and other human activities:

1. is it sustainable?

2. does it support maximum biodiversity?

You could argue that sustainability implies biodiversity, and I would agree, but I think it's important to emphasize this. Biodiversity is part of resiliance; it is a measure of whether we are doing things right.

I feel that every organic farm should devote some of it's land to wildlife and native plants, and pay attention to what's happening there.

Quoting from You Can Farm: The Entrepreneur's Guide to Start & Succeed in a Farming Enterprise by Joel Salatin

This thread reminds me of a class I took in college called "Literature of the Wilderness" and the term paper assignment was to define wilderness and how you distinguish it from non-wilderness. I got a B+ on that paper.

What is "natural" versus "artificial." Hey, humans are part of nature so plutonium is natural!

These discussions can go on forever.

I too have read Fukuoka, and I would suggest that if you can't spot the contradictions within his methods you need to read them again. For example ALL Citrus trees are grafted to rootstocks in order to produce edible fruit. If you don't agree with that try planting citrus seeds and see what you get. Chances are you will wait ten years for a tree that sets inedible fruit. Fukuoka may have had some good ideas; many of which were adopted by permaculture, but farming by definition creates an artificial environment. That dichotomy is glaringly obvious

even within his own work.

Fig. 3 in top post is a grand demo of ‘waste’ of the oil-to-food conversion process.

We can’t drink gas, only coca-cola, fruit juice, and water; we can’t eat coal or shale or oil sands, or even turf, though the starving do eat mud pies. We eat oranges, beef, some raw greens, hamburgers and sushi. (Say.... )

We are condemned to convert, at great ‘cost’, etc. And so we will go on, extracting, transforming, warring, for that bag of rice, those asparagus with Hollandaise sauce.

This paper **PDF** is of interest - Global Energy Flows and their Food System Components, 2001.

quote: Past efforts to enhance the productivity of human-managed photosynthesis systems have involved energy inputs in non-solar forms – mainly from fossil fuel sources – causing such systems to be non-sustainable from the long-term perspective.

http://cigr-ejournal.tamu.edu/submissions/volume3/Invited%20paper-Chance...

The quoted Hendrickson paper is good. (link is inoperative for me.)

Fig. 3 grabs may attention as well. We often read on posts here at TOD about how dependant agriculture is on oil and yet we see in Fig. 3 that agricultural production is about 21% of the 10% of energy used to produce retail food. This agrees with a statement Stuart made in his recent post that agricultural production consumes about 2 percent of total energy use in the U.S.. This seems to be a very small percentage. I can confirm that the energy inputs ascribed to corn production, at least on may farm, are grossly overstated when used in analyzing ethanol EROEI which as most know here is the object of my attacks on many posts. Surely corn production is small fraction of total agricultural energy use since it, while being the largest volume commodity due to its high yield, is still a portion of the total which I presume includes tobacco, cotton, wheat of all kinds, soybeans, barley, oats, hay, rice, plus all the fruit and vegetables and some I have no doubt forgot.

In any case, corn used for ethanol is still a fraction of total corn production which this year is estimated by the government to yield a carry out after all usages of 1.4 billion bushels. There is ample corn for anyone who wants it. So the point is that energy used for corn production is a smallish fraction of energy used for agriculture which is 2% of total energy usage. And the energy used from corn for ethanol is a fraction of that amount. In my mind this puts the lie to EROEI which I have pointed out is wrong because it compares energy "apples and oranges" and commits the cardinal sin of omitting price which is a critical factor in resource allocation and can not be left out due to whim. This puts the nails in the EROEI analysis coffin when applied to ethanol. Since EROEI is the cornerstone of the anti ethanol argument, ethanol has won the argument.

This is wrong on so many counts I don't know where to begin.

Firstly, low EROEI is not the 'cornerstone' of the anti-ethanol argument - the cornerstone is the non-scalability of the non-energy inputs like water, land, soil, etc.

You are pointing out that industrial ag is a small % of our total energy use. A low EROEI then means a very small (overall) addition to our total energy use - thats all that means.

Corn needs natural gas fertilizers and pesticides to grow in addition to diesel for the tractors. It also requires energy to irrigate in places that dont grow dry land crops. Once processed, in order to turn it into usable liquid fuel, great amounts of electricity (natural gas and coal) are then combined with large amounts of water to deliver an end product that only has 60% of the BTUs as gasoline.

We are therefore using 5 or more scarce inputs to create a weak substitute for one scarce input.

I assume by the content of your post that you work in the corn/ethanol industry.