Housing Market Again

Posted by Stuart Staniford on April 11, 2006 - 12:59am

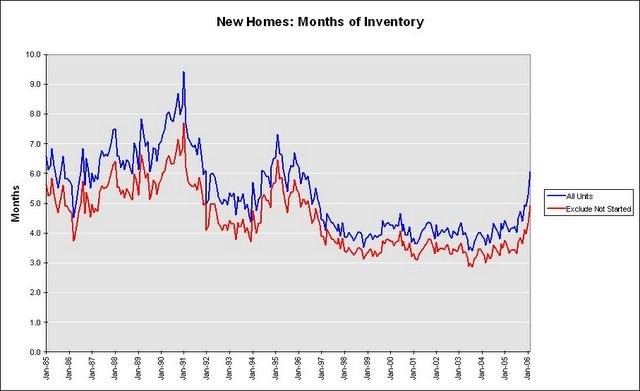

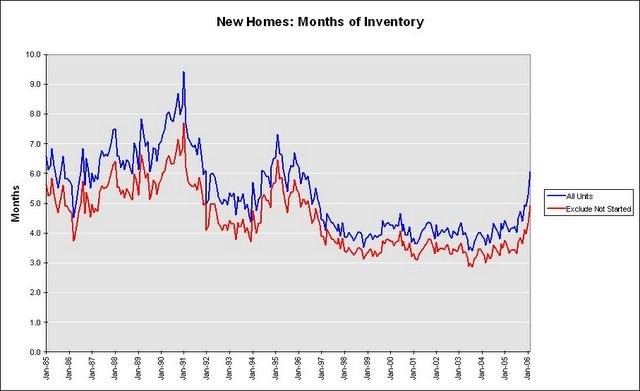

Just a couple of quick graphs found on the econ blogs. The first, from Calculated Risk (one of my favorite blogs) is very striking:

The level of inventory is not high by historical standards, at least not yet, but the rate of acceleration in the last few months is really quite dramatic. How would you extrapolate that over the next year? It's hard to say, but the previous inventory peaks didn't start with nearly such an aggressive attack as this one is starting with.

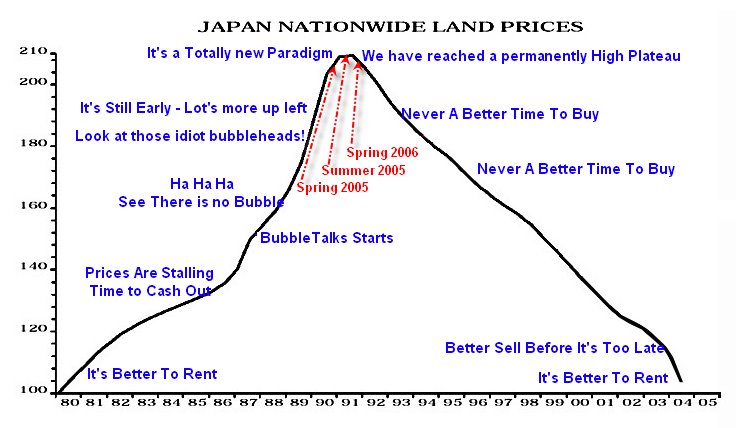

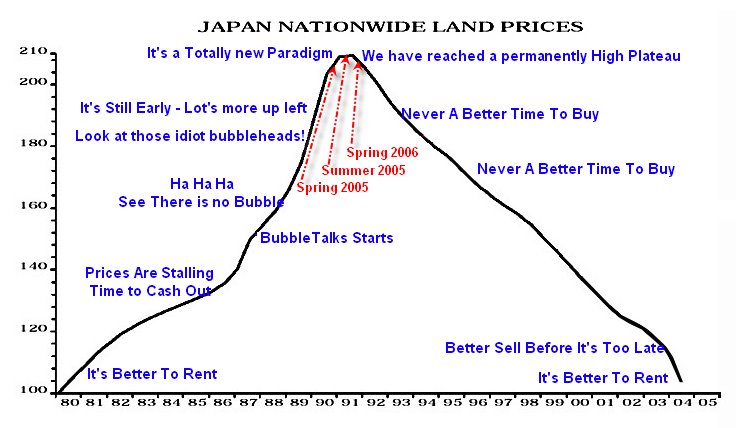

And then here's Mish's opinion of where we are using Japan in the 1980s-1990s as an analogue:

I don't think this is literally accurate, since I don't think housing prices have started to drop yet on a nationwide basis. However, they're certainly dropping in quite a few regional markets.

That was half the point of the stabilization fund I mentioned here on April 1st. The public won't accept higher gas taxes (at least, not yet), but I think we would stand a much greater chance of using pricing to encourage conservation if we create a stabilization system that also gives people the win of less volatility.

Prices for a barrel of oil have more than tripled since 1999 (when refiners paid an average of $17.46 bbl), but worldwide demand in that same 7 years has continued to increase.

I get your point, but we have to say that history has shown us two things: a reisistance to change, and an ability to change given a "shock."

It is undetermined if/when events will conspire to make a "shock."

Humans are very adaptable creatures, which can be both a strength and a weakness. It seems that we can and even want to adapt to anything, given enough time and exposure to it, even undesireable conditions or situations (Even, in fact, torture).

Arthur Koestler's seminal classic "Darkness At Noon" covers this well.

A shock isn't whats needed, whats needed is a realization that energy will always be expensive. Cars, homes and infrastructure are long term investments and if you think expensive gas is temporary, then it won't inpact your decisions.

Taxing gas now won't do any good. It's redundant and regressive. If a bunch of new supply comes on line and the price of oil drops back to $25/bbl, then we should phase in a few extra dollars in taxes. But if we are already plateauing then taxes are too late to change behavior in time to make a difference.

I don't think that "shock" (psychological event) can be defined beforehand.

There's a whole sub-family of web pages on the housing situation, www.dailyreckoning.com touches on it, www.anotherfuckedborrower.com is a good one, one called patrick.net but it's really hard to find, of course it's the best one but I got there everyday and still can't tell you the URL. Something about "bay area housing crash continues" but that's all I can give you.

Housing in the US in general is highly leveraged, highly speculative, etc. It's as bad as the old dot-com bubble before it popped if not worse.

;)

The bloodbath won't be really evident until 2007 IMO. A good statistic to follow will be the number of foreclosures. When the lenders start getting told to rein in their huge portfolios of bad loans, there will be carnage. I think the Japan scenario is an excellent example.

But on a national basis, we are probably not so bad. Ah, I found another Calculated Risk graph:

If we assume things were to return to the mid nineties or mid eighties situation, then this says LA is about 70% overvalued (similar to my guesstimate for San Francisco), but nationally, only 30% (a bit more by now).

OTOH, we have this adjustable mortgage issue that a lot of teaser ARMs, interest rate only loans etc are going to start resetting. That peaks in 2007, 2008 IIRC. Assume for a moment that prices stop going up so no-one can refinance their way out of the problem, and incomes continue to stagnate. Then the question is how many properties does that have the potential to dump back on the market via foreclosures?

There would seem to be a potential for a death spiral where ARM adjustments throw more people into foreclosure and the resulting properties on the market increase inventories and further lower prices, which puts even more people even further underwater. It's possible that could depress prices a lot faster than in Japan. The new bankruptcy law won't help the economy in that scenario either as it will tend to depress consumer savings by folks in that situation. However, I don't know that it would really work that way. It seems we'd need to know the numbers to even have a hope of estimating it.

It's conceivable that the system actually has two modes with a bifurcation - if prices don't go down too fast initially, then the death spiral is never entered, and they just continue to float down gently for a decade like Japan. OTOH a shock (a Middle East war and oil shock ?) could push prices down faster (by pushing more people out of work and into foreclosure and then set up a death spiral that went a lot faster from then on).

Finally, I just have no way whatsoever to understand what might be the effects in the derivatives markets. Presumably the reason we have all these crazy mortgages is because hedge funds have been making outsize returns in the short term by taking on all that risk. (Galbraith, in his wonderful little book "A Short History of Financial Euphoria" says the eternal fixed feature of every bubble is that it always seems there is a new financial innovation, but invariably the innovation is really just leverage in a new form - securitization of mortgages, CDOs, hedge funds, etc would seem to fit that profile).

Any guess as to the percentage of current mortgages which fall into this category? I hear news stories about interest only, and no money down (or using equity of an already mortgaged property, or floating rates).

Even if the housing market were not 2x overpriced, that doesn't mean prices can't fall by more than that. Just as irrational exuberance causes poor investments to be overvalued, fear during a crash carries even good investments down below where one might argue they should rationally be valued. I would expect property prices to fall by far more than a factor of two considering how far they've risen in recent decades. I don't think the property decline in Japan is finished either, as it's hardly likely to be immune to the effects of a financial crisis in the US.

That's exactly what I would expect to happen, and I would expect the same positive feedback dynamic to spread to other assets as individuals attempt to raise cash to pay off debts. Value can be destroyed very quickly under such circumstances across a wide range of asset classes, while the value of cash appreciates in relative terms.

You are right to be concerned about leverage as it has the potential to drive a decline very quickly. The derivatives market has introduced a staggering amount of leverage into the global economy.

Also, there are real estate investors with plenty of cash that will buy in SF. I am not sure about other parts of the country. The occupancy rate in SF is too high to justify a collapse. A moderate adjustment is definitely possible, but not collapse. Even after the Earthquake of 1989 did not cause a collapse.

Now, if you are modeling an economic collapse that will trigger less jobs and skew the ratio of jobs that can afford to buy a house versus housing stock, then yes SF will collapse, but this goes the same throughout every region if you apply the same variables.

So, the only way you are right that SF will collapse more than other regions is that SF will lose more high paying jobs versus other regions. This may come to fruition, but I don't see it due to the diverse economy. SF is not based solely on high tech. San Jose is more geared towards high tech. SF itself is not the same as San Jose or Silicon Valley. SF itself is diversed into finance and investment, tourism and cultural entertainment, and high tech.

Lets go with a flu pandemic.

- 'stay in your house' orders - how will people afford morgages if they can't get to their jobs?

- death will lower housing demand, as dead men have limited housing needs.

- jobs that service the workers/businesses in the lock-down zones will suffer.

The russian who wrote a 3 parter at (i think) from the wilderness made a good point: In Soviet Russia, the state owned the housing. Sure the state wasn't getting rent, but what were they gonna do? Find someone else who WAS getting paid to move in?http://www.fromthewilderness.com/free/ww3/index.shtml

What is 'silly' about it? "Silly" because the reality of such would be painful?

How many people live paycheck to paycheck? How many of them have bills that are STILL due? Do you think the tax man won't want to be paid? How about when a large corporation does a 'writedown' on your debt....now you owe that money of the writedown as 'income' to the tax man.

If the choice is the world financial system missing a few beats for a few months or stopping entirely, I think most everyone would choose to skip a few beats.

Your faith in "the system" might be tested. But many of the 'financial system hearts' are old and gummed up with plague. Already starved of O2, missing a beat or 2 means death.

Besides, if mass numbers are going bankrupt that just means a fire sale on real property....a buying opertunity for people who have money.

No, I think the man will get his payments, or you'll be out on the street. Just like the last time, it will be Hooverville time again.

Stuart, aren't you assuming that rent won't drop during this timeframe. If it does, then returning to a Price to Rent ratio of 1982 will require more than a 30% drop in price nationally.

In 2010, there will be 50% more people aged 50-60 than in 2000. So if there were "X" empty nesters selling their family homes in 2000, there will be approximately 1.5X in 2010, except that the selling will be more pronounced because of the energy issues and the economy. But in any case, the Boomers will be trying to sell to the much smaller Baby Bust generation, who to the extent that they will be buying anything, will be buying close to where they work.

High octane petrol is neighing on the 1.4 €/liter mark (that's 6.3 $/gallon). Buying houses far outside town is lunacy for most folks. Far sites or places with difficult access to central cities are taking a big hit.

One of my cycling buds has been in the construction business for 30 years. In the early years of this decade he started building on a site close to the beach, at the same time not very far from the city (20 ~ 30 Km), but with a difficult accesses to it across the river. The first buildings were sold rapidly, either as holiday's flats or as primary living places.

Since the middle of last year he stopped selling. He hasn't sold a flat for more than 6 months, he fired employees who worked for him for 20 years and in a single site he has debts of several million €.

This is just a case I know, but I think it shows the larger picture. At the same time the housing market in the inner town is getting revived, as people repair old houses to sell or rent.

Once diesel gets near the current prices of petrol a much deeper change will take place in this part of the world. What shape will it yield no one knows.

By the way €7+ per gallon of gasoline here; WITH SUV's selling like bread.

Oh, no kidding. I just spent an hour or so reading the comments. One of them led me to this site:

http://marinpos.blogspot.com/

with even more entertainment value. Why pay for cable TV when you can get this for free?

The following article from the NYT puts the housing bubble in an interesting perspective.

Homes Too Rich for Firefighters Who Save Them

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/09/nyregion/09volunteer.html?ex=1145332800&en=7444f2b768619643&am p;ei=5070&emc=eta1

In short, the backbone--teachers, firefighters, workers, even politicians-- of many communities on the East and West coast have been priced out of the market. Struggling to meet its own needs, some communities are either busing in employees or trying to provide housing for those who provide essential services. Even a cursory glance at many of these communities reveals how dependent many of them are on illegal immigration.

What we have witnessed via globalization is a growing division of wealth--in the U.S. and elsewhere. That division will grow worse, not better. Developing countries have neither the time nor the will to create viable middle classes. The U.S. is losing its middle class.

The economic system will collapse long before they "arrive" at the Promised Land. In addition, global warming, energy needs, and environmental decay will put limits on growth even if these countries stretch their hands for the prize.

A simple look at the average wage in China is telling. Even if wages rise at 10% yearly for the next ten years, wages in the West will not be competitive. Furthermore, developing countries show little interest in independent unions or seriously improving regulations for workers. Nor are they especially interested in stopping global warming or protecting the environment.

As I have said repeatedly, there are three forms of arbitrage creating serious issues for all of us: wage, tax, and environmental. And by all of us, I mean developed and undeveloped countries alike.

I would suggest that all here read the WTO's position on labor and the environment and taxation. The short version is: As long as a country's policy makes a level business playing field for all foreign participants in that country, there is no problem. Countries may choose to be environmental friendly or not; they may choose whatever taxation rules they wish; they may choose whatever labor regulations they like--as long as those rules apply equally to all. It is this policy that is creating the global imbalances; it is this policy that is creating many of the problems we are witnessing. As the energy crisis nears and as global warming finds traction, it is this policy that will be our undoing.

Your post (and the links contained therein) touches upon something that has been bothering me for some time now. Here at TOD there appears to be widespread agreement with Kunstler's view on the death of suburbia as the problems of Peak Oil become manifest. A corollary to the death of suburbia is the rise of the city as THE place to live.

I really don't understand how this massive transfer of people from the deep suburbs to urban areas is supposed to take place. Within the city limits of most major American cities you generally have two types of housing: overpriced townhouses and condo apartments in upscale or gentrified neighborhoods and inner city ghettos and rundown neighborhoods. In many places there isn't all that much in between. And in terms of space, many cities, particularly the older ones on the East Coast are already close to saturation.

The nicer neighborhoods are heavily populated by two-income professional couples without kids. These are already out of reach of most suburban dwellers. The ghettos may be afordable, but who is going to want to move into one?

So what is going to happen to urban housing prices after all these suburbanites realize the error of their ways and try to move back into the city? Nationwide declining housing prices isn't going to help at all, because it giveth on the buying side but taketh on the selling side. In other words, a suburbanite who sells his freshly built development home for a big loss is not going to be in any position to purchase even more expensive housing within the city.

I really don't see how a mass suburb-to-city migration is going to work without the construction of massive Soviet-style public housing on the outskirts of the cities. But just don't see that sort of thing happening here in the US.

One other point: not everybody who lives in the burbs has long commutes into the city for his/her job. Cities have long ago ceased to be the magnet for commerce and industry that they once were. An increasing number of suburban dwellers work in nearby office parks or industrial parks. If you commute into almost any city during rush hour, you will see a stream of cars going in the opposite direction. That flow may be significantly smaller than the cars going in, but it does prove that not all city dwellers even work in their own city. As many small businesses have shut down in the older cities, former employees have to go outside the city for work.

So, in my view it's a bit simplistic to look at this whole thing as a clear-cut city vs suburb issue. In any given area one needs to look at the relationship between the center of gravity of population vs the center of gravity of jobs and essential services.

It seems to be an uncommon virtue

I think some people commute from a suburb to an office park, and given the right ratio of housing to transportation costs, could relocate closer to the office.

We may see a lot of home swaps.

The way it always does. Via price. The suburbs will still be occupied, but they will be the new slums.

The peak oil aware financial experts are recommending investing in urban real estate, because they think suburban real estate will tank while urban will skyrocket. Location, location, location. A ghetto now need not be a ghetto in the future.

Ah, but that's because of the "happy motoring" lifestyle. Businesses will be under the same pressures as individuals. They will have incentive to move closer to ports, customers, government services, other businesses.

Hooverville's dotted the landscape of depression era America. They were often little more than small tent towns or even thrown together clapboard shacks, the equivalent of affordable housing for folks who were out of work and run off their property by the banks (for a much more graphic representation, you should check out the film "Ironweed." It is set in Albany in 1930 and is quite possibly the most depressing film ever made). They were named in honor of Herbert Hoover, who had the distinctly bad luck of occupying the White House when the depression hit in 1929. He sort of staggered along for a few painful years, following a lot of bad advice and generally worsening things for the millions of Americans who were out of work until he was replaced by FDR.

Interestingly enough, Hoover was in part elected because of his relatively good performance running relief efforts during the great flood of 1927.

Subkommander Dred

A couple of points before I address Kunstler:

1) I was raised on Cape Cod. I am very aware of the changes there in terms of support services--waitresses, teachers, fireman, etc.

2) I lived for about 20 years in Westchester, NY and in Stamford, CT--and now visit my children who live in Westchester, one of whom works for a TNC.

3) I lived for about 14 years on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

In the last two areas, I moved just as "flood" of new wealth arrived. I knew what was going to happen. At this point, I cannot afford to live in any of these areas. What will happen in each is that as the "oldtimers" sell or die off, the area will no longer be viable for those of moderate income.

To varying degrees, what I have witnessed in each place is the same: A rural area became a suburban area where the division of wealth accelerated. The final effect is a very wealthy class served by a vanishing population that increasingly does not have the means to live there. I have also spent a considerable amount of time studying exactly what is happening with globalization. I am not sanguine, to say the least.

We all are aware of city ghettoes, pocketed alongside gentrified areas. What we are watching in the well-to-do suburbs is something analogous, but not quite the same. People who move to the suburbs do not want ghettoes; after all, that is why they moved there. Companies as well have moved to the suburbs. Shopping in the suburbs is comparatively easy. People can look at a bit of green, as well. Job is close, shopping is close--for some, but not for all. Where does the waitress live? Where the salesclerk?

I do not see the urbanites moving back to the city. I really do not. If anything, with increasing population, the suburbs will become more and more heavily populated. Population density is moving outward. In those once pleasant enclaves for the wealthy--Bedford, for example--zoning laws have prohibited density from getting out of hand. But now, they have become too expensive for those who once lived there. It is as if the density wave hit a wall, saying in effect: Not here. What happens now?

Try to imagine, if you will, all those people flooding back into the city. Not going to happen. There is little room left.

Kunstler plays with oversimplified ideas. I think we agree here.

Unfortunately, most people who comment on these things are themselves rather well off. They do not work for minimum wage, nor is their income median. Rarely do they see or acknowledge the two-bedroom apartment crowded with ten people. Nor are they aware of the poor that live now in cars, struggling to remain hidden. For the time being, we will see increasing poverty and a vanishing middle class.

A slow vice is bringing pressure from multiple directions: population growth, peak oil, the environment and global warming, globalization and the leveraging of cheap labor, taxation, and weak environmental standards. Supply and resource chains reach across the globe, a network of unbelievable complexity. How all this plays out will be rather complicated, I suspect.

Against all this and possibly our only hope, we have an incredible burst of knowledge in almost every area, fed by IT and the Internet. We are in a race to solve some of the most intractable problems we have ever faced, problems that in some way we were destined to face as our species became more and more successful. Within a hundred years, we will see if we have the wisdom to pass through the eye of the needle. Success does have its price.

Senior citizens flock to the city

Good points!

Evidently, you have lived in three places that perfectly typify what has happened to choice real estate and the ability of the average person to afford a chunk of it: Cape Cod, Westchester Co., New York, and the Maryland Eastern Shore.

All three have experienced severe upward pressure from yuppies and the newly affluent wanting a piece of the good life. (BTW, I have very fond memories of surf fishing trips up to the outer Cape with my uncle during the early 1960s. Sadly, it's not quite the same place.)

If indeed there will be greater pressure to move back into the city as Peak Oil descends upon us, then urban prices will rise and that will make it even harder for the person of modest means to do so. It just ain't gonna happen.

Now, I could see the suburbs that ring the major cities start 'densifying', and I could see the far out exurbs languishing and dropping in value, but I really, for the life of me, cannot see a mass migration into the established cities. Take Philadelphia, for example. There is about 3 times the population of the city itself living in the relatively close suburbs, and more further out. These people are not all going to try to move into Philly: there just isn't enough room, and Philly couldn't handle the influx. What will happen is that the close suburbs will become more city-like. This has been the natural evolution of cities - spreading outward. Some eventually become cities onto themselves.

Again, the key thing is to minimize commuting fuel consumption. But that does not automatically mean a return to the cities. The suburbs will become more and more self-contained, and as they grow the commuting will sort itself out by naturally selecting those that are most convenient to where the jobs are and by discouraging growth in those that are not.

I agree that the working and middle classes are going to find it challenging to move their families near work. In Mumbai and Chongjing, you find several couples living together in a tiny apartment. Americans will find quarters that close to be maddening, but what choices will they have? Did you ever see those automat hotels in Tokyo, where the rooms are little bigger than coffins?

If codes are changed to allow it, I could see wage-earners cramping together for the week, then flocking out to the exurbs, and their families, on weekends. Or maybe every other weekend, depending on finances. My wife worked with a woman who came to America to find a job, and hadn't seen her family in years. She just sent money to Africa. This isn't exactly the American dream, but people may find it necessary.

"This isn't exactly the American dream..." has to be the understatement of the century!

I'm talking about commuting distances re suburbia, and you're talking about stacking people in these sci-fi nightmare people pods. Talk about lowered expectations!

And I think it will happen naturally, as prices rise. I live very close to my workplace, and when gas prices were spiking last fall, two people hinted to me that if this kept up, they'd like to rent a room from me. It was said in a joking manner, but I have no doubt that if gas prices keep rising, they would seriously consider it. They each drive an hour to work every day. And if my landlord keeps raising the rent (to cover heating costs, they say), I may welcome a boarder or two.

And what will happen to people who lose their jobs, can't pay their rent or mortgages, and get kicked out? They'll move in with friends or family, of course, even if it means sleeping on the floor in the living room.

Most people here seem to accept that peak oil means we'll have to give up driving alone. But what about living alone? Isn't that just as wasteful?

That would be because they no longer have a job that pays enough, or because their variable rates are now too high. So now they presumably need to move to the city, either to keep the job they have, or to find one?

Either way, there won't be any place to live there - there's now way going to be enough places available. It would seem that this would cause an increase in values in the city, even if it were only relative to the surroundings. So rents will rise, the poor will be excluded, and apartments will go to those who can afford it. The rest will live in squalor on the outskirts - just like many other cities in the world, and like in the US during the depression.

This sort of thing is not new to North American cities. See here for a description of Tent City in Toronto, disbanded in 2002:

http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/44/247.html

This sort of shanty-town could become home to far more North Americans in the future if we experience a rerun of the Great Depression. The erstwhile middle-class in Argentina never believed they could end up in such circumstances in the twenty-first century either, but many of them did.

Check out this recent edition of The Current from CBC radio:

http://www.cbc.ca/thecurrent/2006/200603/20060327.html

Take a look at this aerial from Detroit.

http://local.live.com/default.aspx?v=2&cp=42.341136~-83.075068&style=o&lvl=1&scene=3

778751

http://local.live.com/default.aspx?v=2&cp=42.341136~-83.075068&style=o&lvl=1&scene=3

778751

De-industrialization, white flight, urban decay and ultimately wide spread demolishion has left a city that once was pushing 2 million inhabitants down to about a million (and still shrinking)

Zooming out a bit.

This is dramatic. The left hand side of the aerial shows a neighborhood in definate decline. Quite a few of the blocks have only a few houses on them. Other neighborhoods have entire blocks that are empty. On the right side you can see a more-intact urban pattern. While there are missing houses there as well, it is far denser. Imagine this density over on the other side and you can get an idea how hollowed out this and other cities have become. It's not just residences. Businesses are gone as well. The largest open space on this area is by my guessing a former commercial or industrial building. Countless other examples like this exist elsewhere in the US rustbelt.

It's tragic and quite sad to witness this happen.

It also might be an opportunity for the future. Look around that first aerial and you will see intact streets (potholes not withstanding) and relatively intact electrical infrastructure. I am also presuming the water and sewerage system also remains in place (its easier to leave it in than dig it out) and mostly functional. What I am getting at is you have here is an existing (and grossly underutilized) urban infrastructure that is more adaptable to a low energy future than the surrounding suburbs.

Now, granted there is a reason why this area was abandoned in the first place; a flight of jobs and its rippling effects on the social and ultimately the urban fabric. Still, a low-energy future will turn previously held assumptions on their heads. Right now this land is obviously less than desireable. Now imagine a world where mobility is limited by fuel costs and shortages. These areas depicted above now, become MORE valueble. Distances between places (existing and new) are shorter. Road and sidewalk systems already exist. Infrastructure is largely in place (some repairs may be needed). The land layout is far more conducive to public transportation.

Then add the fact many of these properties are foreclosed or city-owned (and offered up at discount rates in many places). It all adds up to potential rebirth, at the expense of the surrounding suburbs.

Done right you could see new, energy efficient construction clustered just right to make public transit viable, surrounded by urban gardens and farms. Add in business relocations from the burbs as well and some of these rust belt cities could rise from aparent oblivion (thanks in large part to their open space)

It may happen piecemeal regardless whether or not urban govts buy into it. If one does, it may actually work.

Theoretically anyway

Hey, I can telecommute. I like bicycling. I like gardening. This is starting to look good. If I play my cards right, I can go from an "easy motoring" to an "easy pedaling" lifestyle.

FWIW, twenty years ago I was communicating with the 'nets at 1200 baud. That's roughly a factor a factor of a thousand below current systems. Bandwidth, unlike oil, is something that scales. What kinds of distributed jobs will exist as oil drops and we have another 100x or 1000x in bandwidth?

I'm not a cornucopian, and I'm not going to guarantee you anything ... but I do want to note that with a twenty year curve of higher oil prices, a lot of energy will be applied to press the computer and communications stuff further.

Would it not be possible to make very big areas with large McMansions much cheaper to live in if market forces make people make do with smaller living areas and people start splitting up houses into several apartments?

Old technology for mass producing building blocks for apartments can and sometimes is combined with modern computer technology for customization and logistics. You do not have to build thousands of identical apartments to be able to build millions of apartments.

Why should the state build public housing if you have a functioning market economy? It is easy to find market solutions for building houses, use government money for infrastructure that is hard for regular companies to finance.

In most U.S. suburbs there are zoning laws to forbid more than one family from living in a house--also many times laws that state each house must be on at least one-quarter of an acre or something like that. Also laws say you must have well-mowed lawns, etc., etc., etc.

The purpose of such laws is to keep out poor people, and especially to keep poor black people from invading lilly-white pure upper-middle-class and upper-class suburbs.

Poor people and especially minorities are concentrated in inner cities and some rural areas such as Appalachia (coal mines and White hillbillies) and Indian Reservations.

Living in shipping containers?

Man, you really have high aspirations for the human race! :-)

Folks, we are in deep shit.

There is no way monetary policy can help us solve fundamental problems relating to Peak Oil. Bad monetary policy can make adjustment problems worse, but my guess is that the Fed will soldier on with integrity and guts--until the fecal matter truly drowns the turbine, at which point they will (metaphorically) fall on their swords after ratifying and permitting hyperinflation as an alternative to a rerun of the Great Depression.

BTW, the above is only a WAG, not a prediction.

I completely agree with you here Don. Even if Bernanke achieves the best possible outcome under the circumstances, it isn't going to look like success by any current definition and history will remember him harshly as a result.

I always appreciate insight about this from those who know more about economics than I do.

That means that we have to have a major deflation before we have a major inflation.

The deflation really means simply a drying up of the money supply through a lack of liquidity -- banks stop making loans and do whatever they can to get people to default on existing loans (like raise interest rates!) because that way they get to take real world physical assets and wealth into their posession. Yay for them.

But that can't be the end of the story becuase the national debt has to be eliminated since it can obviously never be repaid, and even less so in a deflated money supply situation where dollars are scarcer and therefore worth even more. No, but once the assets are firmly in the hands of the banking system then the national debt is meaningless and at that time they must rapidly increase the money supply and pay off the debt with what will be worthless dollars.

So thats my take, we'll have both inflation and deflation. And the money powers will benefit as they always do.

As far as people and jobs go, if you like to eat, you'll do what you're told and leave that rfid chip in your hand (or forehead if you were a debtor hahaha) alone. (Ok this last sentence is pure self-indulgent speculation ...)

Are you calling TEOTWAWKI?

Anyway, I have more than fifty pounds of coffee safely hoarded and am accumulating more as supermarkets have specials.

Welcome to the 70's all over again, but worse.

http://www.firstamres.com/pdf/MPR_White_Paper_FINAL.pdf

The UK is probably a better analogue than Japan. Prices rose steeper than the U.S., then flattened through 2005 and have been rising in 2006 thusfar.

http://www.housepricecrash.co.uk/

Japan suffered a 10 year bear market. Could that happen to us? The interesting thing for me is that we have not had long term bear markets in stocks or housing here in the US, because our belief has been too strong. Our confidence has been too high. The '02 stock market drop cought itself (at very high P/Es in historical context). Why? I think it's because investers just couldn't "believe" a bigger crash was happening.

The most interesting question I see, as we face peak oil, peak minerals, peak markets, etc. ... is whether we continue to believe in bull markets, or somehow (like the Japanese) come to believe that decadal bear markets are possible.

http://www.usatoday.com/money/economy/housing/2006-04-04-real-estate-usat_x.htm

All components were built in factories and delivered to site.

5 story apartment buildings for urban application took as little as 90 days to construct.

It would make sense to advocate something similar for the the urban infill required to convert the surface parking lots that dominate our urban space.

With a smaller apartment than is typical in the United States, or with more people living in the same apartment, as was typical in the 1920's, we could see an enourmous rebound in the urban population.

It will be critical to be in urban areas for other reasons post-peak.

The rail hubs typically are in urban areas. Food and goods not produced locally will be delivered by rail and will be difficult to transport large distances from these rail hubs post-peak.

Thanks

1) Japan has one of the oldest populations in the world.

It is one of the few countries in the world to have more people over 65 versus under 15.

- They have a very low fertility rate. 1.4 versus replacment rate of 2.1

- They have have a very low marriage rate with many twenty-something women living with their parents instead of forming new households.

- Immigration into Japan is almost non-existent.

- The population is now declining.

- Real estate in Japan is still relatively expensive.

Hmm... I wonder why real estate isn't doing better there ??Urban areas are certainly not all alike. Phoenix relates to its bioregion much differently than say, the Seattle metro area to its own bioregion or than Minneapolis does to its bioregion.

While there may be similarities, there are very significant differences in these urban/bioregion relationahsips.

So suburban farms may be significant in some changing cities, but not in others. some cities may fry up and wither away, resulting in their populations moving to other areas -- urban, suburban, rural -- in the same or other bioregions.

The mix of housing and work opportunities combined with the successful integration of human settlement into the bioregion. This has to do foremost with successful sustainable harvesting of energy and water and food.

Mix climate change into the scenario along with resource conflicts, and we have a guaranteed intersting life. Maybe short, but certainly interesting.

Are any government or business entities looking at human settlement in terms of sustainable culture within specific bioregional resources?

There are fundamental difference between US and Japanese economy. US economy is based on financial and consumer sectors. Japanese economy is based on manufacturing and trading sectors. The service sector work force in USA and Japan is 80 and 42% respectively, while the manufacturing and trading sector work force in USA and Japan is 10 and 46% respectively. Because of this different economical structure, the stock market behaves differently between these two nations. One of the most important indicators for investors for US market is a consumer sentiment index by University of Illinois while the important indicators for Japanese market are the machinery purchasing orders for factories and the Tankan review of economic sentiments by corporate executives. Because of different economical structures, economical bubbles have different implications between USA and Japan. I think that Jim Puplava made some good comments about the difference of bubbles in USA and Japan in his radio program of financial sense news hour. He argued that inflation rather than deflation will happen in USA because of different natures of bubble economies. I quite agree with him.

I think that the comparison between USA and Japan is not really informative because of this economical structural difference.