Predicting Future Oil Prices

Posted by Dave Cohen on March 6, 2006 - 1:01am

- Can we predict the either the short term price (the front end) or the futures price (the back end) with any accuracy? What is the meaning of oil futures prices on the back end? Does this reflect a real structural adjustment in the oil markets reflecting fundamentals or is it a matter of spread trading (speculation, thereby hedging risk) and profit taking in the market behaviour (internal trading practices)?

- What is the history of the price of oil (especially after the oil shocks of the 1970's and structural re-adjustment that ended in 1986) and what were the assumptions guiding oil prices after that period that obtained until relatively recently (about 2002)?

- Do oil futures prices trends reflect a cyclical or structural change in the prices in the future? What's the difference or does this really matter? What's the perceived cause of these trends?

- Oil at $15-30 a barrel? by James Hamilton at Econbrowser (2/22/06) -- shorthand is Hamilton

- Do Oil Futures Prices Help Predict Future Oil Prices? (pdf) from FRBSF -- shorthand is FRBSF

- The Future Price Of Crude Oil by Paul Stevens for the Middle East Economic Survey September, 2004 -- shorthand is Stevens

- The End of Cheap Oil: Cyclical Or Structural Change in the Global Oil Market? by Herman Franssen for the Middle East Economic Survey February, 2005 -- shorthand is Franssen

- Paul Horsnell thinks we are moving to a sustainable long-term price level from the Oxford Energy Forum, Issue #62, 1st quarter 2006 -- shorthand is Horsnell

Can we predict future oil prices?

I will not bury the lead, as they say in the journalism business. Even without considering (in my view, probable oil shocks), our ability to predict future prices in the next year or two (on the front end) and price further out (on the back end) even considering market fundamentals and a structural adjustment in oil prices is impossible given the large number of independent variables that must be considered. To state the obvious, if there were some reliable magic formula that allowed traders to predict short and long term prices, the commodities markets as in oil or in other basic minerals (eg. copper) could not exist in its current form. You can't predict the future. Uncertainty is basically what gambling is all about. Following your instincts based on incomplete knowledge, what you bet on follows from those intuitions and what you currently know. I will say here that lowering the NYMEX oil LSC oil price based on robust inventories that have been built up to hedge against probable future oil shocks/shortfalls is not rational behaviour. There is always a risk premium involved when you are betting on prices. In addition, front end upward movements in the price seem to depend on external events like hurricanes, unrest in Nigeria, the Iranian nuclear situation etc. This strikes me as sensible because if you're an oil trader, your willingness to take the risk underlies the buy transactions you are making because you are aware that sudden possible disruptions may make your locked in (albeit higher) price low enough to allow profit taking later. Of course, this can be hedged through the practice of spread trading. Perhaps oil traders who contribute to TOD can illuminate these practices. One particular point I'd like to see addressed is the nature of the correlation between the short end and the back end prices especially in the current timeframe.Is There A Purely Statistical Model That Predicts Oil Prices?

A posteriori, we know that no such model can exist as I stated above. Beyond hedging, profit taking and the like, a perception of the market fundamentals needs to be known to some extent and data pertaining to supply & demand in the real world confirming these fundamentals can only be known to a limited extent. It's ironic that the world's most important, fundamental resource that fuels "economic growth"--namely crude oil--is not subject to close transparent review of the production & consumption numbers. Let's look at two sources that tell us that models based solely on the historical market behaviour itself are essentially useless for telling us anything about future prices.Here's what Hamilton posted recently regarding the possibility of $15 to $30/barrel oil in the future.

One way to approach such a question [of the plausibility of a return to $15 to $30/barrel oil] is to use regression analysis to try to predict, say, next quarter's change in the natural logarithm of the real oil price on the basis of currently available information. But the regression coefficient relating next quarter's change in the real oil price to the current quarter's change in the real oil price is essentially zero....Given this result, Hamilton concludes that a random walk might be best for predicting future oil prices. Here's his data if "we use plus or minus two standard deviations to form a 95% confidence interval and convert from logs back to levels, we arrive at the confidence ranges implied by the table [below]".Even the constant term is statistically indistinguishable from zero (p-value = 0.51), meaning one really has no basis in the historical record for anticipating a tendency for real oil prices to move in any particular direction from here.

| quarter | lower bound | upper bound |

|---|---|---|

| 2006:Q1 | 43.57 | 82.63 |

| 2006:Q2 | 38.16 | 94.34 |

| 2006:Q3 | 34.47 | 104.44 |

| 2006:Q4 | 31.64 | 113.79 |

| 2007:Q1 | 29.34 | 122.72 |

| 2007:Q2 | 27.40 | 131.39 |

| 2007:Q3 | 25.73 | 139.91 |

| 2007:Q4 | 24.27 | 148.33 |

| 2008:Q1 | 22.97 | 156.70 |

| 2008:Q2 | 21.81 | 165.05 |

| 2008:Q3 | 20.76 | 173.41 |

| 2008:Q4 | 19.80 | 181.79 |

95% confidence interval for real oil price

(2005 $ per barrel) at specified horizon if the

real oil price follows a Gaussian random walk

To see a complete table out to 2010 look at Hamilton's post. Obviously, as he himself point out,

... surely professional forecasters can do better than this, one would think. Another way to judge how uncertain experts are about where oil is headed is to look at the volatility that is implicit in crude oil options prices. Using the Black-Scholes formula, one calculates an implied volatility from current values of options on NYMEX that corresponds to an annual standard deviation of 32%-- the identical number as from the historical volatility above.Stating the obvious, these results are useless and depend solely on a random walk to try estimate market prices without considering market fundamentals. Let's consider the more sophisticated FRBSF modelling for predicting future oil prices--again without any regard for market fundamentals and the the long term structural adjustment that is happening in the markets regarding oil prices.

First the authors Tao Wu and Andrew MacCallum state their intentions.

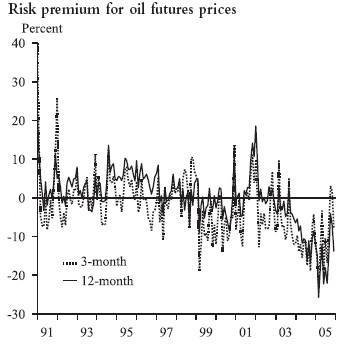

Is the price of oil likely to rise further, or will it decline gradually, as it did in the mid-1980s? A natural place to look for an answer is in the markets, where oil traders are knowledgeable about the industry and where their profits ride on making sound investments. This Economic Letter discusses how to forecast future oil price movements based on information from both the oil futures market and the spot market. In particular, we conduct a series of forecasting exercises and compare the performance of models that use oil futures and spot prices in an attempt to find the one that performs best.Initially, they consider the "risk premium for oil futures prices, defined as the difference between the oil futures price and the expected future spot price from the Consensus Forecast’s survey. The difference is expressed as a percentage of the current spot price." See the paper for further details.

Risk Premiums for Future Oil Prices - Figure 1

As they note, although the average risk premium for future oil prices is about zero, there is a large amount of volatility over time. From this they conclude that "oil futures prices are not necessarily the best predictor of future oil prices". So instead, Wu and MacCallum consider the extent to which he current, or spot, oil price helps predict future oil price movements. Since I am only giving a brief overview here, I suggest looking at the paper itself for the methodology used. Four models are considered.

We formulate four models based on oil futures prices and the spot oil price.The first is a random walk model, which predicts that spot oil prices will stay at their current levels. This is the simplest statistical model and provides a benchmark to evaluate the forecasting performance of other models. Second is Hotelling’s model, which predicts that the future oil price will be the current spot price adjusted for the interest rate.Third is a futures model, which predicts an oil price level in the future identical to the current futures price level. Fourth is a futures-spot spread model, which uses the spread between the current futures prices and the spot price to predict movements in the future price of oil.As it turns out, the futures-spot spread model performs best--a technical description of how spread trading works is provided by Stevens. The Hotelling model does second best and slightly better for longer time ranges. However, as far as predicting future oil prices goes, great uncertainty reigns.

Based on these data, the “futures-spot spread” model projects a slight increase in oil prices, with the spot price rising to $65 per barrel by March 2006 and $67 per barrel by December 2006. However, the accuracy of such forecasts is quite low. For instance, we can only say that, with 90% certainty, the spot price in March 2006 will be between $55 and $74 per barrel.So predicting future oil prices based solely on models of market behaviour itself is not really possible as we would expect. Whoever could do that would truly be a rich person indeed. Ironically, I will say that the Nymex price on 3/3/06 stands at $63.67/barrel which is close to the March 6 price of $65/barrel quoted by Wu and MacCaullum....taking into account the relationship between current spot and futures prices instead of considering only the raw futures price can significantly improve forecasting accuracy. Prediction errors, however, are still substantial, and accurately predicting the future price of oil seems as elusive as ever.

A Little History and the Old Orthodoxy

The papers from Horsnell and Franssen describe the history of oil prices in the period 1986 to about 2002 or so. This time sequence starts after the oil shocks of the 1970's and early 1980's and when oil prices collapsed in mid-1980's. Looking back, the collapse was largely due to 3 factors- High prices had promoted efficiency and fuel switching which adjusted demand for oil downward.

- OPEC--especially Saudi Arabia--turned on the spigots and flooded the market.

- New non-OPEC production came online (the North Sea, Prudhoe Bay)

By the early-to-mid-1980s, price induced efficiency gains and fuel substitution caused oil demand to decline, non-OPEC supply to rise and demand for OPEC oil to contract sharply resulting in a collapse in oil prices. Some oil market analysts correctly predicted at the time that the high oil prices of the early 1980s were not sustainable and were bound to fall, but few predicted the extent of the decline in demand for OPEC oil and the subsequent oil price collapse of 1986.This "Goldman-Sachs" consensus became a dogma during this period. From HorsnellThe 15 years following the 1986 oil price collapse were characterized by low global oil demand growth, steady annual increases in non-OPEC oil production, large OPEC spare production capacity and ample refining/tanker spare capacity. As a result, a new consensus developed, which lasted for almost two decades – that the long-term equilibrium oil price was somewhere around $18-20/B (average price from 1986-2000).

The view was very precise, in that the long-term oil price was generally put as being between $18 and $21 per barrel. Indeed, the market’s perception of where to place the back end of the crude oil futures curve very rarely strayed outside that $18 to $21 interval over the whole period from 1986 to 2002. The $18 to $21 range became the touchstone for views of what represented normality, and any hypothesis that suggested prices could be higher than that range was considered heretically abnormal. Governments thought in terms of that range, as did financial markets.As Horsnell describes it, what he calls an "ex post rationale" developed for this orthodoxy. If prices started to exceed the $20/barrel range, investment in non-OPEC capacity would increase the supply side and demand growth would decrease due to higher prices. Prices would fall back to the nominal range.

So, some analysts in the early 1980's had predicted that the oil shocks period represented a cyclical change in oil prices and prices would return to low levels after an adjustment period. In other words, there had been no structural change in which prices would reach a new much higher sustained level. These analysts were right for the period in question from 1986 on until about 2002. Thus, the view was re-established and reinforced that higher price periods were always cyclical in nature and after an adjustment period would return to normal levels. We see this idea directly in the view of CERA and Daniel Yergin today and expressed in Stevens writing in September of 2004. I will return to Stevens below since he presents the most direct arguments against so-called "depletionists". That would be most of us at TOD.

During the period of orthodoxy described above, oil futures prices on the back end stayed around the nominal $18 to $21/barrel range. Even during the Gulf War of 1991, when there was a spike in oil prices, the market had faith. For example, writing in High oil prices are here to stay, Jeremy Baker of UBS says

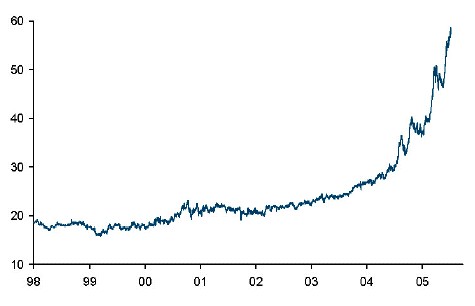

During previous price spikes – for example, during the first and second Gulf wars – spot prices soared but the two-year future price remained relatively constant.This graphic from Horsnell shows the trend since 1998.This suggested that the global oil market looked beyond the short-term crisis and focused on longer-term stability.

Five-year Forward Price of WTI, $/b.

Source: Barclays Capital -- Figure 2

As you can see, the forward price has turned upward dramatically since about 2004 and continues to rise to this very day as does the short term price. As this phenomenon continues a new orthodoxy is emerging to explain it. However, the issue of why current and futures prices are high is contentious but standard viewpoints converge as we shall see.

Cyclical or Structural? The Emerging New Orthodoxy

There are two basic positions about what these high futures prices indicate. If you are a structuralist like Horsnell or Franssen, then the view is that at least over the mid to longer term (5 to 10 years) out, high prices will continue albeit with great volatility. Horsnell puts it directly.Very few would argue today that $20 is the correct long-term price for oil. However, it should be noted how that change came about. The rejection of the orthodoxy was not the result of any debate or examination that concluded that supply and demand side responses were not as strong as had been assumed. Instead, the rejection came about simply because oil prices rose, and then kept on going....But in seeming contradiction to this position, Horsnell still presents this view, which I regard as the new orthodoxy.For the marginal cost of non-OPEC oil to have followed the path of Figure 1 would be something of a stretch in our view, but that concept is still in the wild. Likewise, political discussion of the oil price still follows some very well worn grooves. Throughout the current year, various politicians have argued that higher prices are either the fault of observation, i.e. if the market had a better understanding and better data it would produce lower prices, or that the rise is temporary, or that it is simply the result of speculators or other dark forces. Even now, among many analysts and consultants there is a belief in a sharp increase in non-OPEC supply growth that will create a sustainable price collapse, i.e. they would say that old theory was perfectly correct but it is just a tad slower to operate than was first believed.

Our view is the sustainable level of long-term prices is that which creates enough investment along the entire supply chain to maintain a reasonable degree of spare capacity, while also ensuring that producing countries are able to maintain some growth in employment and in per capita incomes. That would argue for a long-term price of at least $50, with higher prices needed into the medium term to allow for some catch-up, particularly in the downstream, from the last decade of the 1990s.This new orthodoxy rests on fundamental assumptions used by the IEA, Yergin, Stevens and others. These are as follows.

- The "call on OPEC" by OECD countries will increase production by the cartel member countries, especially Saudi Arabia and generally in the Middle East.

- Rising demand in Asia is straining the supply/demand equation but is still not a significant enough factor to keep prices rising indefinitely.

- Unconventional sources (eg. the Canadian tar sands) will easily replace harder to develop conventional oil.

- Lack of E&P and refinery investment, especially in the 1990's by the oil industry and further downstream in the supply chain accompanied by the unexpected rise in demand in the early 2000's caught everybody by surprise.

- Since there is a long lag time between discovery or reserves growth from existing resouces and actual new production, there is a "catching up period" which will last at least 5 years from the present.

- There is still growth to come from non-OPEC producers, especially Russia but also from many other medium size smaller producers like Angola.

Supply cannot easily rise to match demand because of underinvestment in both exploration and refining capacity in the past two decades. High prices are, of course, encouraging a new wave of investment, but new oil fields and refineries take years to come on stream. A case in point is a new deep water offshore production project off the West African coast. The time horizon from appraisal to final development was around 10 years. New refineries also take a long time to construct and projects are further complicated by environmental regulations, which means many new refineries are being built and planned in emerging market regions. We’re not running out of oil, it’s just that the oil industry hasn’t kept pace with demand.The new orthodoxy is based on a structural adjustment but there are some who believe we are simply in a price cycle. Hamilton excellent article cites Yergin in It's Not the End Of the Oil Age from which I take this quote.

Where will this growth come from? [the usual argument that there will be an additional 16/mbpd of new capacity by 2010] It is pretty evenly divided between non-OPEC and OPEC. The largest non-OPEC growth is projected for Canada, Kazakhstan, Brazil, Azerbaijan, Angola and Russia. In the OPEC countries, significant growth is expected to occur in Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, Algeria and Libya, among others.Perhaps he is now taking a different view considering Katrina and geopolitical events, but Yergin is on the radical side of the new orthodoxy and seems to actually assume it here according to the assumptions I list above. Prices will go down and end the current volatility. And finally, on to Stevens who takes on the Peak Oil commmunity directly. First, he believes (or did in 9/04) that higher oil prices on both the front end and back end were due to spread trading ie. speculation. This precludes any actual structural change in market fundamentals. Second, lack of investment in the oil industry was due to pressure to maximize returns to shareholders. Stevens agrees with the "depletionists" that prices may remain high but those of us in the peak oil community may right (in the medium term) for the wrong reasons.

It would be a delicious irony if, after all this time, they [the "depletionists"] were eventually proved right but for entirely the wrong reasons. The key issue is investment by oil companies in exploration and production. Although this argument could be extended to other stages in the oil industry value chain, this short paper will focus only on the upstream....So why are we Peak Oil people wrong? I will number the three reasons within the quote (there are actually four reasons).Simple economics argue that high prices produce a supply response creating a self correcting mechanism. However, this tends to neglect the lead times involved. In upstream oil, the lead times for new capacity can be between five-to-eight years. Thus the crude shortages resulting from the current outflow of potential investment funds could be around for quite some time, together with their resultant high oil prices.

Their [the Peak Oil] argument, based upon the constraints of reserves, is seriously flawed for three reasons. [1] First, it assumes a fixed stock of “conventional” oil reserves. This ignores the role of investment and while I will argue below this is a key issue, it has no part in the “depletionists” battery of arguments. [2] An even more egregious error is that it ignores the potential from “unconventional” oil reserves. [3] Second, it assumes future oil demand will grow without limitation along the lines suggested by the IEA. Again, there are a great many arguments which can be deployed as to why various drivers will eventually slow such growth. These range from environmental and security of supply concerns together with consumer governments in developing and transition countries using sales taxes on oil products to raise revenue, to name but a few. Finally, [4] it ignores the feedback loops provided by markets. Growing shortage would increase prices which would in turn reduce the quantity demanded and increase the quantity supplied.Concluding this section, the new orthodoxy contains various elements but in any case, the argument is that the current high prices both on the front end and back end (futures) is cyclical. The only disagreement is whether 1) prices will go down, perhaps radically (eg. $30/barrel, short cycle, Yergin) or 2) prices will go down and level out at a higher price (eg. $50/barrel, structural, Horsnell). For the Yergin price quote, see Yergin: Oil price should settle at $30 price floor (pdf) from Petroleum News, June 2005. Everyone agrees on higher prices in the short or medium term but future prices will stabilize at some lower level. So, that's the new orthodoxy in thinking about oil prices. I will now argue against this new orthodoxy for oil prices or, at the very least, the assumptions that underlie it.

Analyzing the New Orthodoxy

To start with, Horsnell makes the following sensible point.The move up in prices is not a shock, it is an adjustment towards a sustainable long-term price level. It has been in progress for too long, and has been too gradual to be a shock, and indeed that has been the major reason why the macroeconomic impact has been relatively benign. Had prices gone from $20 to $60 very quickly there would have been a strong impact effect. As it is, a sustained move up with relatively gentle year-on-year changes has allowed demand growth to continue fairly robustly.

But let's refute this new dogma on a case by case basis considering its underlying assumptions as I laid them out in the last section. Here are my responses to Stevens' points about "depletionists" as outlined in the previous section.

- Re: First, it assumes a fixed stock of “conventional” oil reserves. This ignores the role of investment...

Yes, the Peak Oil community does assume a fixed stock of conventional oil that Stuart estimated at URR is 2250 ± 260 Gb in Extrapolating World Production. But the real point is that we are very concerned about investment--the concerns being that the major IOC's spend more money doing "drilling on Wall Street" acquiring the assets of smaller companies than for E&P and particularly that new investment is not finding much new oil. Recently, Bubba posted 2005 Exploration Round-Up. Prior to that, I posted The End of Exploration?. The point is that money invested in E&P has less and less of a payoff because there is less and less new oil to find (unless the IOC's are increasing investment somewhat because whatever they do manage to find will be worth so much more in the future--a point that Hamilton seems to make). But for now, to see oil supply elasticity with respect to price as far as ExxonMobil goes, see Stuart's graph at Speaking of bumpy plateaus. The assumption most notably made by the IEA that throwing trillions of dollars at the problem will fix the production side of things is incorrect according to everything we know from actually examining the data. Investing in existing fields to try increase recovery rates may raise the URR for the fields in question eg. using CO2 injection for EOR but that has a very limited applicability generally.

- Re: An even more egregious error is that it ignores the potential from “unconventional” oil reserves.

Not at all. What we have noticed about "unconventional" oil sources is that when they are successfully produced, as with the tar sands of Alberta, the production costs are enormous and the oil is more difficult to extract and process. In other words, at best you can only get small incremental increasing production year-on-year. If these tar sands are producing 3 or 4/mbpd by 2015, so what? That would not nearly offset depletion from existing giant fields like Cantarell or the anticipated deepwater peak in about 2012.

As far as other unconventional sources go, so-called oil shales are decades away from commercial production and even if they do go into production, they would face the same problems that the tar sands do as just stated above. As for Venezuelan heavy oil and bitumen, there are large difficulties both upstream in production and downstream on the refining side. There is no evidence this source will come to rescue. And on and on regarding GTL, CTL, etc.

- Re: Second, it assumes future oil demand will grow without limitation along the lines suggested by the IEA.

This gets back to the assumption about rising demand in Asia and other developing countries. Actually, the overall production decline rate is the limiting factor as Stuart describes in Hubbert Theory says Peak is Slow Squeeze. One point underlying this view is that Asian countries like China and India will engage in the kind of structural adjustment (efficiency, fuel switching) that the US did in the 1973 to 1986 period, thus slowing demand growth. In fact, it's the IEA (as Stevens notes) that believes in ever-rising demand, not the Peak Oil community. At the very least, demand will finally hit the supply wall (and probably already has at the current prices).

- Re: it [the peak oil argument] ignores the feedback loops provided by markets. Growing shortage would increase prices which would in turn reduce the quantity demanded and increase the quantity supplied.

Thank you for this lesson in Economics 101. Increasing production is the problem and faith in the laws of supply & demand will not solve it. Yes, higher prices will make some additional oil economical to produce but throwing money at the problem will not induce God to put more oil in the ground.

- Re: There is still growth to come from non-OPEC producers, especially Russia but also from many other medium size smaller producers like Angola.

Even ExxonMobil admits that non-OPEC production will peak about 2010. It has been Russia and increasing deepwater production from places like the Gulf of Guinea, the GOM and Brazil that has kept non-OPEC production flat for the last few years. On the other side of the equation, the North Sea is in steep decline, there are legitimate questions about Mexico's ability to maintain production levels, Canada may be able to make small incremental increases in their exports but the more general truth is that the large majority of non-OPEC suppliers have peaked.

- Re: The "call on OPEC" by OECD countries will increase production ... in the Middle East.

If Saudi Arabia's recent flat production (see Cigar Now) indicates a future trend, George Bush holding hands with Prince Abdullah won't make much difference. Of course, there is a wide range of opinions about the Aramco Black Box ranging from Simmons' "Twilight in the Desert" to theories that Saudi Arabia is increasing production incrementally to control prices. Beyond that, there are the questionable reserve increases in the 1980's and recently Kuwait appears to support theories that the reserve inflation in OPEC countries at that time was a fiction. In addition, Nigeria is a total mess. Venezuela's production has never reached production levels it had prior to the work stoppage in the 2002/2003 period. So, there are certainly legitimate concerns about OPEC's ability to increase production going forward.

On the other hand, future oil prices may eventually level out but at a price well over $100/barrel because Economics 101 no longer works anymore for an increasingly scarce commodity like oil where the cost of new production goes up and up. In addition, the industry is running out of skilled labor who know the business. I'll end with a quote from Hamilton . Talking about the possibility of $15 to $30/barrel oil in the context of why the oil companies are not selling lots more oil at the current high prices now as a hedge against a collapse in the price, he says

Maybe the argument against hedging is based on the notion that these futures markets are so thin that if Exxon-Mobil starting selling in a bigger way, it would quickly move the futures price. I'm not convinced that such an argument is correct. The futures price is linked through arbitrage to all sorts of other prices in a very big world, and a thin market is no reason to believe the price should be anything other than the fundamental equilibrium value. Increasing sales need not bring about a big change in the price even if the market is currently thin. And even if the market thinness argument were correct, it still makes no sense to me as an explanation for not buying some degree of a hedge, if what you're really worried about is the possibility of a precipitous price collapse. Such concern would go beyond the joke about the economist who won't pick up a $20 bill on the sidewalk because his theory predicts it shouldn't be there. In this case, we won't pick up a $20 bill that we're absolutely sure is right there on the sidewalk on the grounds that, if we took it, we don't know how many more $20 bills will float down to take its place.Predicting future oil prices? Who knows? But I'll bet we'll never see $30/barrel ever again.Specifically, that's two $20 bills for every barrel the oil companies choose not to sell forward. At a few million a day, that might add up.

My question for Michael Lynch is this,"If you take your own investment advice, why aren't you bankrupt yet? And if you are being paid to give investment advice, why haven't you been fired for incompetence?" Obviously Lynch is an economic disinformation shill. Lynch and Yergin's backers want the small investors to short oil so the big boys can buy long on the cheap.

We may be wrong, but the actual traders are slowly buying into peak oil. Long oil a year ago was $10 lower than the spot price, now there is about a $3 premium for long oil.

But oil speculators -- at least those in the futures markets -- don't take delivery of oil.

Speculators clearly impact forward contract prices, and we have seen their significant impact over the last years in the reduction in oil futures backwardation: where six year forward contracts traded at a 30% discount to spot prices in 2004, they now trade at no discount.

But since speculators always sell before taking delivery of current month contracts, they don't compete with parties that take delivery of oil. For example, if speculators raised prices on near-term oil contracts, delivery-taking buyers could wait for the price decline that would occur just before the contracts matured, as speculators exchanged out of their contracts for farther-forward contracts.

Is my understanding flawed? If not, how can futures market oil speculators impact prices any more than betting on a horse race affects its outcome?

Some how the money that speculators bring to the market has to result in increasing inventories, otherwise money would disapear. I think inventories are growing is because more money is flowing towards oil futures.

I would just like to add a few items that I have been looking at the last few days.

On the EIA's international petroleum website they have a listing of what looks like all the major types of crude oil and their geographic locations.If we take $62 or $63 as the current price of oil, it is easy to see from this website that not a lot of current crude production is of the top-quality, WTI/Brent standard.

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/dnav/pet/pet_pri_wco_k_w.htm

The three Saudi grades listed range from $49-$55. Excluding the Malaysian Tapis Blend 44º at $65, the good stuff appears to be Nigerian Forcados at about $61. And we know 20% of that just left the market. Interestingly, the average price in the US, home of WTI/Cushing is only $51.43. Where did the other $10 go?

The point here is that the Nymex Futures/WTI spot price is based on a benchmark grade of crude. I believe Simmons addressed this subject recently. I will paraphrase. This is like tracking the price of automobiles by only looking at Rolls-Royces.

Second, every Thursday Bloomberg News conducts a survey of about 50 analysts and traders on what the price of oil will do in the next week. Recently I have been tracking this survey. What Bloomberg never tells you is the record the survey has. It has been wrong three of the last four weeks. Last week's results: of 49 analysts, 16 said the price would rise, 13 said it would stay the same, 20(or 41%) said it would drop. I'm not sure what "stay the same" means, I count it as an abstention. Anyway, the consensus was wrong, the price went up.

It is also important to remember that although historically there has been no real trend in oil prices, it is becoming a widely recognized fact that the "cheap oil" is gone. It is costing more and more to find and "produce" oil. The price of oil rests largely on the initial production cost of that oil. This price is undoubtedly going up fairly drastically. In fact we know this anecdotally from the increased interest in tar sands and other types of non-conventional crude. But its effect on the long-term price of oil needs to be appreciated.

I agree with this, that predicting these prices is fundamentally impossible given the uncertainties.I should mention, too, that I am not an economist. My background is actually not all that different from Stuart's: I work in cryptography and software design, and I have a bachelor's degree in engineering from Caltech. However I have a great respect for the economist's way of thinking, at least as I define it.

Not everything that is conventionally thought of as 'economics' falls into that category, though. I think a lot of the material you quoted is pretty much BS. All these people claiming to know the future, to know what the stable price of oil is! It's junk economics, IMO. I've posted before on studies showing that so-called expert predictions are generally pretty worthless. Highly-paid economic advisors can't beat chimpanzees throwing darts. Most of these guys are operating an enormous scam, a confidence game. I think a lot of the people you are quoting, the ones who claim to know the future, fall into that group.

Where I look for reliable information is the markets themselves. And what the markets are telling us, as in those tables you quote from JDH (a good economist, btw), is that the future is highly uncertain! Look just three years out and ask for 95% reliability, and all the market can tell you is that the price will be between $20 and $180! I worked out the figures for a narrower spread, and if we want just 68% reliability, the range is still $34-104. There's a full 1/3 chance we will be out of that range by the end of 08. So the markets are actually very consistent with your statement I quoted above. They are telling us that the future is highly uncertain, so-called experts notwithstanding.

You are half-way to enlightenment ;-).

Prices just are.

Or they are some mix of signal and noise, and no one really knows how much is signal and how much is noise at any point in time.

Options let people bet on how much is signal and how much is noise. If you disagree with the market consensus on the question - if you think the markets are over- or under-estimating the degree of certainty in a price estimate - you can take a position in the market and make a profit if you are right.

if the 1970-2005 experience is representative of the near term future, then ...

We can put ourselves back at some points in history where such projections would be less safe than others. If we'd calculated in 1970 for instance, we'd get a very different idea of oil price variance than we would later, in 1980.

Q: Does anything related to "peak oil" imply a change in variance?

This data comes from option prices (that's what the Black-Scholes formula is about) and allows us to directly read out the market's opinion of the range of likely future prices.

So at this point, it appears that the answer is no, considerations of "peak oil" are not changing the market's opinion of future volatility.

This is the point I was making above, that the market not only gives us price estimates, it also gives us error bars on those prices. You can bet on the prices or you can bet on the size of the error. Either way, if you have a strong suspicion that the market is getting it wrong, you can profit. If you think that variance should increase in the next few years due to greater volatility caused by Peak Oil, you can take positions in out-of-the-money options, which conventional market thinking will set as underpriced.

I made the point earlier that actually, most people here are in luck. They live in a world in which money is just lying around for the taking. Since most contributors here strongly disagree with market prices, either in absolute terms or in terms of the chances of hitting certain extreme prices, they see a market that is full of low-risk, high-profit opportunities. It's as though you could buy a lottery ticket where you had a 95% chance of winning, instead of 0.00001% or whatever. That's how the world looks for a Peak Oil true believer.

People in the markets are foolishly giving their money away! And all it takes to get rich for the Peak Oiler is the courage of his convictions. Oh, and he has to be right, of course. But most people don't have much doubt on that score. At least, not until they have to actually put money down, and they suddenly realize that there must be some reason the other guy is willing to bet against them...

You can "check" future performance with a Black-Scholes calculation based current prices, but such a check still carries an assumption.

* - assuming current market characteristics hold, and that no "game changers" appear

As an example, look at Fletcher's posting below:

http://www.theoildrum.com/story/2006/3/2/234845/7384#23

and my response. He predicted that oil would not fall below $55 again. I pointed out that the markets saw a 30% chance of that happening before 2009. If he is 95% sure he is right, he can get free money from the market, just like a 95% winning lottery ticket. He can cash in for six thousand dollars a contract with, in his view, almost no risk.

Another example was a few days ago:

http://www.theoildrum.com/comments/2006/3/1/3402/63420/367#367

Don predicted 5 to 3 odds that oil would hit $200 by 2010. The markets say the odds are more like 1 in 20! I showed him a contract that would have probably a 95% chance of being profitable (in his judgement) and that would have a better than even chance of making him 20 times his investment! How's that for a 95% successful lottery ticket?

This leads to a point I made yesterday. It's fine to come up with your own opinions on the odds of various events. But once you are informed of the market estimate, if it differs from your own view, you have a rather uncomfortable choice. You can change your estimate to match that of the market. That's what I do.

Or, if you insist on holding to your own ideas and believe that the market is wrong, you have to accept that there is free money available that you are passing up. There are positions you can take in the market that will be profitable with very little risk. The greater your disagreement with the market, the easier it is to find such positions and the greater the profitability, as in the examples above.

Since it is of questionable rationality to pass up free money, it follows that it is questionable whether it is rationally possible to disagree with the markets. It could be that when you are informed of a market consensus, you are more or less forced to agree with it! Sounds bizarre, but I think there may be some results in the economic literature along these lines. It is an area I want to look at in more detail.

Or you may remember the way I divided it, anybody who names "a price" is either:

- assuming no wildcards (not a good bet with real money)

- think they know the wildcards (fools)

- or are just taking a swipe at it (without real conviction)

I don't really think you should push the "true believer" thing too hard, because it rapidly becomes a straw man. A true believer has to be someone who:- believes "peak oil" is true

- believes that "peak oil" will be the strongest market factor in the next 10 years

- believes that no wildcards short or long term will upset this applecart

So really, a "true believer" has to understand oil, but not markets.To say that the price of oil will never fall bellow $50 should be made very carfully by a trader. As an economist who adheres to Peak Oil, I would claim the same. As a trader, I would even be willing to bet on falling prices, although not necessarily at the present.

A True Believer is not necessarily a True Trader. Being 95% certain in the mid to long range on the markets doesn't help much. Entrance and Exit points on the market do. On the market: 2 + 2 = 5 (-1). Its more like dancing, not like empirical science.

a demand destruction event is the only thing that will slow terminally higher prices.

Hedging is keeping Alaska Airlines and Southwest from sinking into bankruptcy due to higher fuel costs (for the time being). You can do it too. There is even a new commodites fund that invests 55% of capital in crude oil futures (DBC).

If we are wrong about peak oil, and the oil price crashes, you lose some of the investment, but you get to live in a growth economy for a few more years, so you win anyway.

Its not as easy as y'all make it seem on the markets.

First of all, living as an expatriate - my US TAXES for the last 7 years have to be filed, although I haven't earned a dime in the states since then, in order to play on the US Futures market.

Second, your broker or bank will want security that you can pay IF IT JUST HAPPENS that the markets go the wrong way.

Third, IF they go the wrong way in the short term, you have to cap your losses and try again tomorrow.

Fourth, my solar rig is supported by the German Gov. My loan is 1% interest.

Look at other things too of course like who is involved, or local water tables - many marginal wells are "half-full" and although now profitable again or close to it, they still may require helpful water pressure to recover (extremely important point in the USA as noted last week by another poster).

My point is that you can make investments that will pay off if oil prices go up. If oil prices go up, you win. If they go down, you win too, because the economy will do better, and you will pay less for energy. Of course, if all investments become worthless, then you lose. That's like playing a chess game and having a giant knock the board over and take all the pieces. No chess move will win you the game at that point (and you are probably playing a new game, called "Run from the Giant!").

You get a 1% loan to get solar power panels? I wish our goverment would do that.

analysis of project economics suggests that, in general, an oil price of $US24 per barrel for West Texas Intermediate and a NYMEX natural gas price of $US 4.00 per million British thermal units would yield a rate of return in the low to mid teens for both steam assisted gravity drainage and integrated mining operations in the oil sands.

Given the low short term price elasticity of demand for oil, a given quantity of oil may require a price of $120/barrel at a global level of economic activity comparable to today (~5% US unemployment). Slow economic activity down (say US unemployment = 12%) and the price of oil could drop to $40/barrel for the same quantity of oil.

Light Crdue Oil futures will not go below $55/bbl after mid-May 2006.

Would you like to know what the markets think? 30% chance of falling below 55 before December 2009.

If you think this is way too high, and are very confident prices will not fall that low, you could make a nice chunk of change. You can sell Put options with a $55 "strike price" and a December 09 expiration for $6,000. You get that six grand up front. The downside is that you will be obligated to pay $1,000 for every dollar the price falls below $55. So really as long as it doesn't fall below $49 you will still be OK.

You could buy a lot of nice things for $6,000. And if you're really feeling daring, you could sell multiple contracts and make even more. (In practice, you'll have to keep quite a bit of money on account at the brokerage to sell so-called "uncovered" options like this.)

My larger point is, opinions here are what economists call "cheap talk", meaning that they don't commit you to anything. Opinions expressed in the market, OTOH, are backed up by real money. They mean the person expressing the opinion is risking his own livelihood on being right. That inherently gives them greater weight and credibility. It is why I continue to pay close attention to what markets are telling us. Market information is exactly the opposite of "cheap talk".

I suspect there will a substantial "hurricane" premium in the market come this summer. Whether that is meteorologically sensible is another matter. AFter that inflation and continued depletion of existing major fields will kick in.

Look at these poor bastards in South America. They've been listening to me for years. Why? Cuz I got "commie cred"? Yeah, wrong, I've been playin' that stuff for years(my luck's running out). It is because I have understood oil for years - and know how to play my knowledge. Rafael goes nowhere without my paratroop 'C'-squad covering him.

Once you get it(Get IT), it's not hard to figure out. There are only a few of us on this planet that have the gift. Most of us congregate here. Others are less sociable, so to speak.

Once you understand oil, you can live in peace. It is God's best joke. Only a sense of humour will allow you to laugh. That's why we love Dr. Stranglelove so much. Only those with advanced minds like Kubrick's understand funny-ass shit.

Consider someone who lives 4 gallons away from work. I have coworkers like this. Meanwhile, I may be buying a condo only a liter of fuel from work in a crappy area. Given the oil peak, who's the dummies? If the condo doesn't pan out, I could move to an apartment a liter away or less.

For someone 4 gallons away from work, a price of $5/gallon would be BRUTAL. $40/day. $800/month. That would be my mortgage! One of these coworkers is rather racist. As non-whites move near him, he moves farther out. He is liable to regret the gamble he's taking. He has 5 years until he retires, so the race is on. Will he retire first? Or will gas prices ground his car first?

Maybe soon enough, speaking in terms of "gallons away" may replace "minutes away" in suburban parlance. I'm merely the first.

One problem with predicting "prices" is that the commodity (or whatever is being priced) in question is not being compared to something objective. Oil prices are being quoted in USDollars. But what is a USDollar worth? The same objection would be valid with the comparison to a bushel of wheat or an ounce of gold. Sorry to all the gold buggers out there - the value of gold is also only measurable in comparison to something else.

Could it be that the price of oil is rising simply because the dollar and other fiat currencies around the world are falling? (If that be the case, then the rising price of oil is certainly structural because money supply is expanding structurally and can't be turned around quickly.)

This became clear to me, living in Europe, while watching quoted oil prices (in USdollar) rise in the short term, and prices at the pump remained stable. This "phenomenon" only lasted a couple of months, but it made something clear - prices, even when adjusted to inflation, are hardly absolute measurements.

Another example: It was often quoted that tar sands could be produced at 30$. The price of oil rises, and the price of "production" also rises...

For this reason (if not only this reason) the structuralists must be right - if perhaps for the wrong reasons, to quote a phrase:-)

Our system (the human desire for foreknowledge combined with the media) definitely promotes people who profess detailed knowledge of the future.

That in itself is a selection bias. Consider ten people in a room, 9 think the future is uncertain, one guy steps forward to go on Wall Street Week ... and chances are he is a broker.

Well, that's the other factor. Many of these predictors have an interest (direct or indirect) in having an answer.

Consider ... has the EIA ever said "sorry, we can't do a projection this year?" It's their job. They've gotta come up with one ... in uncertain times as well as ... well, deciding which times are certain is the third level of the problem.

We live in the present (obviously) and the only data we have is behind us. We can aspire to the best possible prediction based on past data ... but it is in my opinion impossible to calculate a confidence level in that prediction. We might know the frequency of wild cards, sudden changes, in the past ... but such statistical information can never tell us what wild cards will turn up next week, or next year.

Geez Louise, what happens to 10 year oil futures if (shazzam) cellulosic ethanol suddenly works?

So what I've learned (I think I'm old enough to be experienced and young enough to be flexible) is that a good fuzzy idea will carry you though. Plan for a range of outcomes ... and turn off the TV when people start talking about where the markets will close in December 2006.

My father is (still) an indepedent producer in Ohio. 1986, as the prices were falling, I faced the question of following in my father's footprints or going liberal arts. I chose liberal arts - I remember telling myself that it will take 30 years for the oil bull market to return. Ok, I was wrong. It didn't even take 20 years:-|

I knew in my bones that the market had made a "decision" was being ruled by other laws - even though I couldn't explain them at the time. Capacity was simply too big.

Now I'll argue the other way around. September 2003, the market gave me a signal that the tables had changed back - right before I went looking for the reason and found Peak Oil. Too bad I wasn't in a position to invest...

If Yergins were right and the situation were able to adjust itself, it would take another 10 to 15 years to do so.

As someone whose family was producing oil from an areas which peaked in 1893, however, I can only say one thing: Yergins is wrong.

Thanks for another excellent detailed post.

So the question really is will prices:

A) stabilize at a new range, say $50-65 or

B) continue to go up because supply is now truly constrained - higher prices no longer cause an increase in supply fast enough to hold prices stable.

Clearly prices can come down in dollar terms if there is a catastrophic shrinking of economies due to depression but I don't think this is your point.

Seems to me the key over the next few years is can exploration and pumping replace existing field decline? If yes, new stable prices. If no, the sky is the limit until the economy crashes. Isn't this what TOD has been tracking the past year or so?

- production is not going to change a lot

- demand is not going to change a lot

- demand looks to grow faster than production

- alternative energies are not going to change a lot

So to the extent that current prices are based on current supply and demand, they should also not change a lot.The obvious short-term wild cards are:

- current prices actually include a "fear factor"

- political changes could change supply or demand

- economic changes could change supply or demand

The obvious long-term wild cards are:- new major projects

- new major technologies

- more political/economic changes

Anybody who names "a price" is either:Everyone reading your above list should reflect on every element and decide how it 'feels' for them. I would try to put some bounds on some of them:

-The probable extreme bounds of risk premium are $2 to $15 ($5 to $10 is perhaps a more realistic narrower band).

- new major projects take 5+ years to affect production

- as typically do new technologies

On the positive side I would say there is still some scope for various EOR to increase both ultimate production (though probably only a little) and rate of production in short term.The key is in the economic and production interaction...

- If global growth continues at or above trend then peak oil (demand vs. supply) will be reached by 2008 at latest

- If significant recession occurs then demand will reduce and the price of oil will drop, possibly to near $40

But, demand is close to flat out current supply. Any major suppy constraint will cause an upwards spike in oil price, that spike is almost unconstrained, it could be $10 or it could be $200 or more.The US will enter recession soon (within a year) and that will have significant effect on oil prices. What will be frightening is how little that effect is.

For it's worth I expect overall downward pressure on oil prices in the next couple of years based on probable supply and excluding geopolitical events. But even in that scenario I don't expect an oil price of $40. I do expect to see a price of $150 within 2 years, though; that may be my own distorted perception.

I think the markets are pricing in about 10% of the peceived 10% probable risks, I don't think their risk assessment covers it.

Perhaps there is my problem with Halfin's argument: markets totally discount extreme possibilities, maybe regardless of their actual probability. I do not accept the markets' prediction of risk and probability: theirs' is a self interested and blinkered assessment (as is mine, no doubt).

Calculations of risk based on past performance are no guarantee of future volatility.

Off with the philosopher's hat, on with economist's hat: What can we know about supply and demand, because those two factors (and, in a sense, ONLY those two) affect prices. Immediately we run into problems, because both aggregate demand and aggregate supply depend on a bunch of different things. Also, in your formulation of the problem you have left out the most important variables as unknowable, namely supply shocks based, e.g. on Nigeria or Iraq or Iran or (for that matter) Russia collapsing into nothing but blood and fire. Well, those kinds of the things, and the related risk premiums are the 800 pound gorilla, and if you avoid Kong, the problem becomes almost (but not quite) uninteresting.

Off with my philosopher's hat, now on with the battered old sombrero, my social psychologist's hat with a specialization in the theory and history of collective behavior, all from a symbolic-interactionist perspective. Collective behavior deals with things such as mass hysteria, panics, lynchings, riots, tulip-bulb manias, and irrational exuberance. Briefly, speculators are herds of sheep lead by judas goats. Because buying and selling decisions are based on expectations, and expectations (at least in the short run) are highly volatile, it is futile to even try to predict price movements.

Conclusion: People who claim knowledge of future prices (at least in the short run) do not know my friend, Jack Shiterman.

From 030106 NYT:

Today in the gulf's offshore region, 362,000 barrels of oil a day, out of a total of 1.5 million barrels, remain shut off, along with 15 percent of the region's natural gas production, or 1.5 billion cubic feet a day.

Ok, then this:

The company( Shell) said that three-quarters of its total capacity of 450,000 barrels a day had been returned to production.

But one of its biggest structures, Mars, which produced about 140,000 barrels of oil a day before Hurricane Katrina, is not expected to restart until the second half of 2006.

3/4 0f 450k is112+k. But 140k is still down according to the NYT.

Now this:

With no realistic option of towing the platform (Mars) back to a shipyard, repairs had to be done at sea. Anyone know where

250k bpd Thunderhorse is? I'm betting at sea under repair as well.

Obviously the TH production has not been counted (never started, but was expected to be online by now).

Then here:

Chevron, which lost a major platform (Typhoon) during Hurricane Rita, said that its output was back at two-thirds of its prestorm capacity of 300,000 barrels a day.

So Typhoon had a 100k bpd.

We're at 280k bpd lost not counting 250k TH.

Back to article:

Hurricanes Katrina and Rita destroyed or damaged 167 offshore platforms and 183 pipelines

Today, as much as one million barrels a day (!) of capacity, or 6 percent of the nation's total refining capacity, remains shut down. Most of that should be back by the end of March, according to the Energy Department.

To recap: one million barrels a day (!) of capacity, or 6 percent of the nation's total refining capacity is still offline.

280k bpd just from Shell and Chevron shutin. 362k bpd total

shutin (so BP's Thunderhorse has never been figured in) and

production from Conoco/Phillips Jolliet and Noble Jim Thompson

are not included (more than the 80k bpd difference just from these

2 platforms) and the 167 destroyed platforms produced what?

Bottomline: The shutin numbers are bad. At least 35% od production is still shut in.

James (I am not an economist)

This means that what we need to do is to compute the difference, supply minus demand. But as anyone knows who has worked with statistics, if you have two uncertain figures of about the same magnitude, and you take their difference, the error bars explode catastrophically. Not only is it impossible to meaningfully estimate the size of the difference, you often can't even estimate its sign.

That, I think, is clearly the case with oil. We have a number of different groups who have done extrapolations like this, and they all get different results. Some show supply outpacing demand, and some have it the other way around. Demand itself is highly uncertain, with some forecasting an enormous surge from China while others see Asian demand leveling off. And of course supply is just as controversial, with various groups coming out with very different numbers for expected future production capacity. Worse, since demand and supply are very close to being equal, and they each have these enormous uncertainties, it really is impossible to say what the sign and magnitude will be of their difference.

This is what the markets are telling us, with the enormous standard deviations displayed in the table Dave reprints from Econbrowser. Oil has a two-sigma range of $20 to $180 after less than three years! Clearly this allows for either extreme result, an enormous glut or a terrible shortage. Or anything in between, of course.

IMO people are just fooling themselves when they try to pin it down closer than this. This includes both the conventional-wisdom-spouting "experts" Dave quotes, and, frankly, many contributors here who are equally certain about an upcoming oil disaster and its economic consequences.

The markets are saying that they don't know.

The underlying reality probably does.

Which would you listen to?

If some "event" later this month (e.g. the Nigerian rebels succeed in eliminating 1 mbpd from production, as they say now is their goal) causes oil to spike to, say the $70 - $80 range, that same paradigm shift among OPEC can easily cause OPEC to decide in another couple of months that $70 is a "fair" price. And so forth.

I have to say that if I were OPEC, that's how I would be thinking. What in the world are they doing producing flat out? It's just not in their self-interest.

Incidentally, I suspect that it is precisely the fear of such thinking taking hold that causes the people who pay Daniel Yergin's salary to cause him to pound the table saying that the next stop is $30.

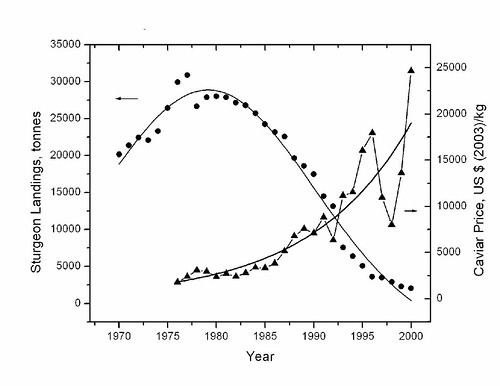

We have a few instances in recent history of natural ressource depletion, can we learn from it? Ugo Bardi published an article about that in the last ASPO conference (How General is the Hubbert Curve?), for instance:

- Whale bone depletion:

-Caviar:

His conclusions:

In his presentation, he gave the following prediction (don't know exactly how he produced these two curves corresponding to two different URR values):

Our economy is, however, "dependent" on oil. Economy crashes - do prices do the same?

Look at past recessions - any dramatic effect

on prices? How long after the Oil Shocks of the 70-80s was it before NYMEX even STarted trading futures... any lag there???

What about the 1970s- stagflation recessions and oil prices. There must be some Basal Level of consumption even for a world economy on Idle. And then what IF the markets finally/suddenly wake up from the Popular Delusion to Peak Production... max out above ground storage capacity and ramp up futures...???

The markets are probably in almost uncharted territory, it is quite difficult to play them with any certainty. That is both a danger and potential boon. It is a relief after the past couple of years' mostly range bound stagnation. Expect volatility.

Let's assume that 50 billion miles are driven each day, at 84 GBD production. So (in our simple model) 84 GBD "supports" 50 million car-miles a day.

Then, as more people want to put cars on the road..and drive more miles, the price will have to rise to confine car-miles to the 50 billion that are "supported" at this level of production.

As production falls, the number of miles a day that can be supported will go down accordingly, and the price will need to go up to curb demand to the new level.

This model doesn't give a straight answer, but it does indicate a method to approximating a real number.

In today's dollars, what would the price of oil have to be to make the Canadian tar sands profitable?

Clearly, some very big investors have considered the cost to produce a tar-sands barrel of oil. Clearly, they are assuming we will reach a point where it will be profitable. What is that point?

I am suggesting that this may be one way of getting a partial handle on its coming price.

If you look at Chevron's proposed "Billions" of dollars investment to get into the Alberta game last week, you can bet the majors think the price of oil will stay above $25, maybe $30 forever.

What happens if declines of conventional oil lead to an inability to meet demand at current prices? Price goes up and more oil should get to the market. But if these more difficult sources like sands and shale can't ramp up quickly the price might spike and cause great demand destruction by turning the economy on its ear.

This would result in a major "correction" in demand to a much lower level. This means less supply is required, but the economy is not very robust either and the first thing to cut out is tar sand production. At that point only the cheap oil will make up the supply. Tar sands and shale are still the expensive guys on the block and don't get produced. You then have to wait for demand to reassert itself and bring prices back up.

So it seems like you have to meter in production of tar sand at the same rate that conventional oil is dropping for it ever to be a viable approach. Start tar sands too soon, and it's way too expensive compared to conventional. Start too late and the world economy crashes killing demand and again you don't need tar sands. Only a coordinated run up in price with careful substitution of expensive oil for cheap oil appears to be a viable business case. This works even if overall world production goes down, as long as it goes down in an orderly way substituting ever more expensive oil along the way.

And the only way you can substitute for cheap oil is if there isn't any left (in some one elses hands) to come on the market and undercut you on price. Big plays in tar sands sound like the oil companies know peak oil is here and are trying to manage the transition.

So, though someone may have accurately said that a certain piece of tar sands was profitable at $30 bbl price in 2004 today's equation may say $50 bbl. It is a very moving target and very difficult to predict years ahead and commit many $billion on the basis of what may be a temporary spike in oil price.

I would be surprised if oil stayed over $200 in inflation adjusted terms. But that's just a guess.

Excellent point! For any kind of honest analysis we must make a clear distinction between real and nominal prices. And as you probably know, the Federal Reserve (and other central banks) is a group of men and women who will behave in ways that cannot be predicted--though we can make guesses based on our knowledge of how political pressures make impacts on central banks.

To a close approximation, at high rates of inflation the rate of inflation is linked to the rate of growth in the money supply. (No, I do not assume that the velocity of money is either constant nor stable, but I do claim it matters little at extremely high rates of growth in the money supply.) Now we all know there is a huge debt burden out there, and this burden will get much much very very much heavier in a recession.

If there is a hint of deflation or a rerun of the Great Depression, then I think most central banks will use the equivalent of the hydrogen bomb to combat this threat: They will greatly and abruptly increase the rate of growth in the money supply by monetizing rapidly increasing government deficits. Note that this is easy to do through open market operations--and easy to do even while vehemently denying that that is what you are doing. However, once some business journalists catch on to what is happening, then expectations go from adaptive to rational on a dime, interest rates and inflation rates soar . . . . and you can forget about how much it costs to mail a letter, because you will need so many stamps that there will be no room for the address.

I used to give lectures on the German inflation of 1923, and someone in the audience would always ask: "Could it happen here?" after which I would always give a dramatic pause, smile, and say: "Could the U.S. ever lose a war and have unpayable debts? How can you think such a thing could ever happen to us?" all with my best Socratic irony.

Don's post hints at the possibilities, he is correct. I will hopefully get back to this thread and explain further, but I must sleep now.

Being a naive investor, but convinced of the reality of PO, I do not have the knowledge to evaluate short term price movements, so I have no intention of trading contracts--just holding them to close to maturity.

(I am aware of the chance for economic depression (bringing down investment values)and resulting in a decline in oil prices. There is also the chance of things getting so bad that futures contracts are invalidated, but hopefully TEOTWAWKI will occur after 2010.)

Now in economic theory, in the absence of speculation and risk premiums, the price of a commodity should not exceed expected LRMC (Long Range Marginal Cost).

However, the real world does not behave that way, for reasons economists--and even more, economic historians--understand.

Briefly, the $12 to $20 number is almost irrelevant even if it is correct.

For one thing, what you are doing (by implication) is comparative statics. But comparative statics omits dynamics entirely (just as in physics) and the issues at hand require way more dynamic analysis than they do the undergraduate-textbook comparative statics approach.

The top executives of Exon-Mobil and the other companies know my friend Jack Shiterman, and they also know how to maximize their own compensation packages. They hire very expensive lawyers to draft their lies for them so as to (hopefully) stay out of jail. Oh yes, they are "The Brightest Guys in the Room," as were the Enron executives.

Saadun demanded a detailed account of the size of reserves in all Kuwaiti fields and reservoirs, including the standards adopted in estimating them and whether they were adopted by local or international sides.

"We must know the full truth on the proven and non-proven reserves and other data regarding the oil wealth," Saadun said.

A more sophisticated understanding can be had by investigating the plans of a smaller start-up operation run by OMNI Canada because they are using a method of refining the oil sands that is far less dependent on NG. It is more capital intensive but claims to save $5 - $10 per barrel depending on the NG price. Essentially, it burns the least useful parts of the collected material in order to refine the rest into light sweet of a very high quality.

The more I think about it, though, the more it seems to me that an interesting dance is beginning to be played out as we may be reaching the "bumpy top" of the peak. What I'm thinking of is a sort of price-smoothing and gradual price increasing effect coming from a paradigm-shift in the outlook of the oil exporting countries, as they try to move short term prices in a smooth and gradual upward direction to obtain what is looking to everyone like a much elevated longer term price structure.

This dance is the result of a complex set of political and economic self-interest calculations by the exporters that goes something like this (think of an Iranian having this discussion with himself):

- We now can see that we should be producing less and conserving more oil both because the price will be much higher in the future and because we ourselves will need an increasing amount of our own production as we try to grow our economy from its present low per capita GNP to a higher level in an oil-starved world. So we want to husband it for our own future needs.

- How do we accomplish this and still get the income we need? We gradually push up the price by producing less.

- On the other hand, we don't want to cause the developed world too much economic pain. We don't want a world depression. Why? Well, for one we don't want to increase the risk of military moves against us. Two, we don't want a depression to cause a temporary free-fall in the price of oil. In a more general sense, stability is good and we're starting to understand that PR can matter.

- How do we accomplish that? We make our moves gradual. We take advantage of price-escalating one-off events like hurricanes and the guys in Nigeria. So when prices spike up, we make it very sticky for them to come down again. We cut back slowly and start talking about a new level of "fair" prices for oil. So a few months ago we said that $50 seems like a "fair" price. Now we say that $60 seems like a "fair" price. Maybe in a few months we can say that $70 looks like a "fair" price.

- In this manner we move the short term prices gradually toward what we all know is going to be a far higher price in the long term. We do it without shocking the world economy. And we gradually begin to conserve our own supplies without anyone taking great notice. In fact the EIA guys will simply ascribe our reduced exports to depletion or to greater internal use.

Now, all of that has nothing to do with classical economic theory of supply and demand, unless you look at studies of monopoly pricing behavior. But I would submit that we are entering the era of oil oligopoly. There are fewer and fewer exporting nations. Thus, oligopoly. That is the pricing model that is becoming relevant today. Moreover, it is a more sophisticated, more PR-conscious, more politically-sensitive model for oligopoly behavior than simple classical economics provides.Unfortunately, oligopoly theory is a mess.

You cannot get much mileage out of game theory; for example, the Nash equilibrium tells you almost nothing interesting that you would really like to know.

Cut more wood, that's what I say.

The economics of exhaustible resources has a mature theory going back to the work of Hotelling in 1931. He shows that profit-maximizing oil producers will attempt to keep a production level such that the price rises gradually, at the rate of interest, about 5% per year with current inflation rates. Depending on how demand adjusts, production will be varied to keep the price stable on this path. This not only maximizes the profits of the producers, it also maximizes the total net economic value of the oil resource.

A couple of other points on this. Even though the oil is being sold for much more than its marginal cost (or even average cost) of production, this does not represent monopoly or oligopoly pricing. A fully competitive production market will follow this same pricing strategy. Each individual producer finds it to his advantage to stay on this price curve.

As an example of a failure to understand this point, see this widely referenced article by Stern in PNAS:

http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/103/5/1650

He is upset that Middle Eastern oil producers are charging much more than their costs for oil. He sees this as an example of "market power" (i.e. monopoly pricing) and a threat to the U.S. national security. But the truth is, this kind of pricing is exactly what is predicted by economic theory, and in fact it optimizes the net economic value of the oil. Oil producers are doing us a favor by charging more for the oil now, so that we use somewhat less today and leave enough for tomorrow that prices will not climb out of control.

Now, I'm just talking about the theory of fully competitive, profit-maximizing oil producers. As you point out, the reality is different and many other considerations will go into OPEC's decisions to set prices. However it looks to me like most of those other factors in fact just reinforce the simple Hotelling model as a reasonable strategy for future prices. And as I mentioned it has the benefit of optimizing total world social welfare, which is not such a bad deal.

We could do a lot worse than to have OPEC and other oil producers keep us on a steady curve of predictably increasing prices, at a modest 5% rate, indefinitely.

Actually, I made only a passing reference to this when I said "Of course, there is a wide range of opinions about the Aramco Black Box ranging from Simmons' "Twilight in the Desert" to theories that Saudi Arabia is increasing production incrementally to control prices"

But it has been on my mind. Since OPEC is no longer a "swing producer" as in the old days with lots of spare capacity, they can only produce less to influence prices, not more. So, they can not set the "floor" by flooding the market. They can only raise the "ceiling" by producing less. I think they're very worried about this because OPEC always wants prices to be in what they perceive to be some "optimum" range regarding the balance of supply and demand--which I suppose we could consider to be the range where their profits are maximized over time.

But I don't think there are widespread signs of even the beginning of such a coherent trend. Countries are typically producing as near to flat out as they can, from what I see in the data. After all, most companies and politicians desire to maximise short term profitability.

However, I do expect at least some countries to adopt policies that, probably somewhat indirectly, move in the direction you suggest. Perhaps Brazil already has. Until the world has clearly recognised the reality and severity of the impending problem I doubt that a global oil reserves conservation strategy will emerge.

Two other points. The global economy is a fickle beast, its vaguaries are likely to disrupt such plans (and might force the price of oil down to near $40 in the next year or so) unless reality dictates otherwise. A steady rise of 5% per year suggested by Halfin is a considerable decceleration from the 30%+ increases of the last 3 years, perhaps a steady 25% increase would be more reasonable.

However, there are trends:

If you live in the Northeast, you know it is going to get cold in the winter.

If you live in the Southeast, you know there will be hurrincanes in the summer.

Throw in the white noise of Iran, Ethopia, Iraq and Saudi attacks and you get a trend upwards, with serious weather releated spikes.

I think this trend upwards will occur for 4-5 more years, then the bottom will fail out for a couple of reasons:

- Many poor baby boomers will be forced out of the workplace through retirement and illness. This massive block of poor retirees will stop buying anything but food, cigarettes, and medicine. These boomers will stop driving to work or at all. Instant oil demand destruction.

- Once this block of consumer stops working (and drawing social security), the country will face a serious recession/depression.