The Auto Efficiency Wedge

Posted by Stuart Staniford on February 11, 2007 - 10:28am

ED by PG: This article was originally posted December 20, 2006. Note that it has been resubmitted to reddit and digg this morning, so do help spread the word and give Stuart some more readers if you are so inclined. Send the link to someone today.

I'll be reasoning mainly by looking at what we did in the 1970s, which was the last time we faced severe energy constraints that bled through into requiring a demand side response.

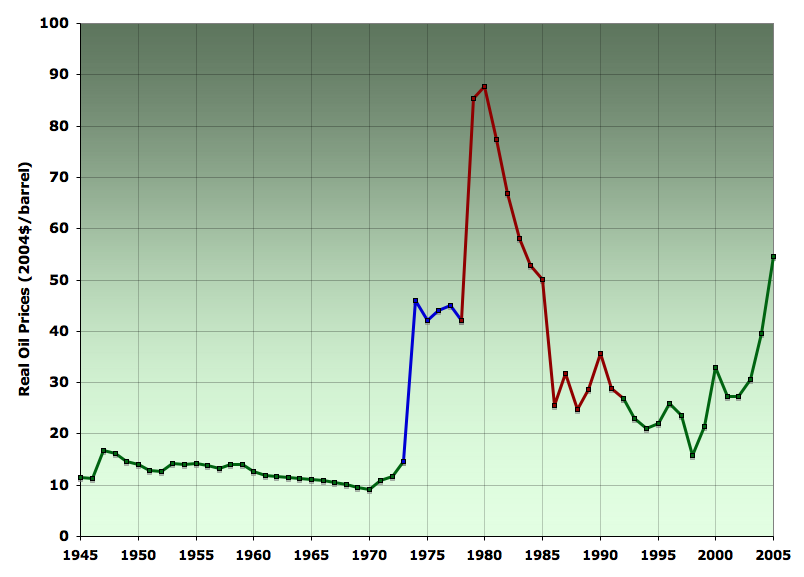

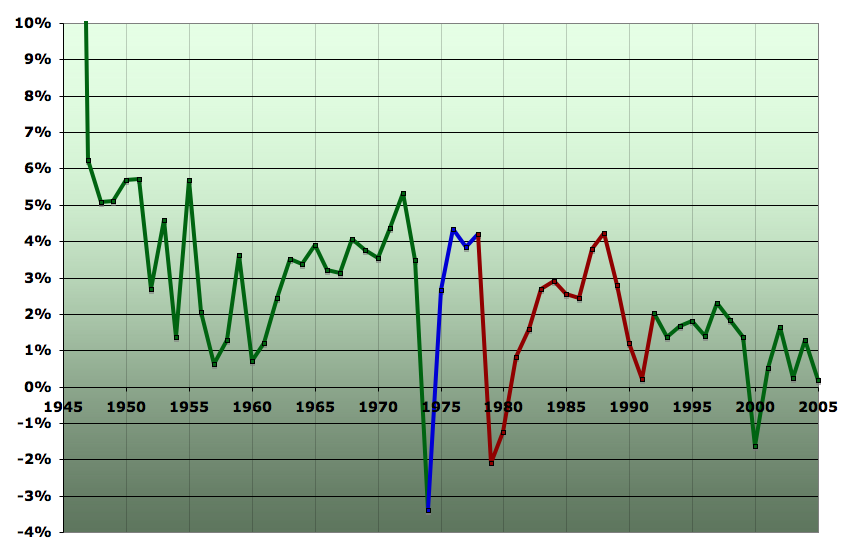

To begin with, let's refresh our memories about the history of oil prices, which tells the story of the oil shocks quite well.

In this graph, like most in this piece, I've adopted the convention of coloring 1973-1978 in blue. 1973 was the Arab oil embargo: the first oil shock. From shortly after the end of the second world war (in 1945 when the graph starts) until the early 1970s, prices were low, stable, and declining in real terms. The Arab oil embargo in '73 caused a very rapid quadrupling of prices, and they have never been anything like as low or stable since then.

I've also colored the period 1978-1992 in red. 1979 brought the Iranian revolution, shortly followed by the Iran-Iraq war. Prices doubled again from the mid-seventies values, and stayed high, though steadily declining, through about 1985. By 1986, prices entered a new regime of fluctuating in the $20s and $30s until the runup in price of the last few years (which I believed to be probably caused by the onset of a plateau in global production).

As we'll discuss below, 1992 was when the period of rapid fuel economy increases initiated by the oil shocks ended.

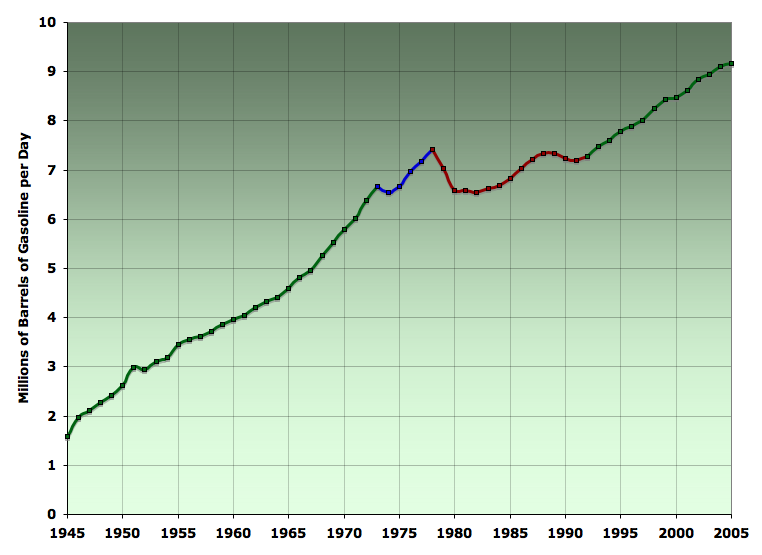

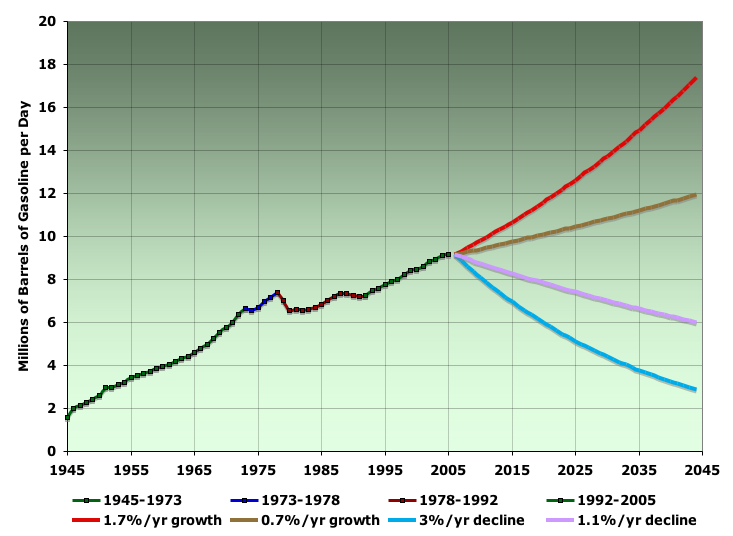

Let's now look at how total gasoline used in the US evolved in response to this history.

We see strong and steady growth prior to 1973. 1973 saw only a minor blip downwards, but growth rapidly resumed. However, following the Iranian revolution, gasoline usage dropped sharply, and then began growing again only very slowly and hesitantly, and did not exceed the 1978 value until the 1990s. Since 1992, gasoline usage has been steadily increasing, though at a slower pace than in the 1950s and 1960s.

It's useful to decompose gasoline usage as a product of two things: the total amount of miles driven, and the fuel efficiency of the vehicles doing the driving. Miles driven is mainly a function of the physical layout of society (where houses, schools, offices, factories etc are located, and thus how far people have to drive to get to them), and human behavior (how often people decide to go to a particular destination, and whether they choose to go alone, share a ride, or to take some form of transportation other than driving). Fuel efficiency is mainly a function of vehicle technology, with a small component of driving behavior mixed in (we'll see an example of how small below).

Here is the total number of miles driven (expressed in billions of miles/day) in the US on all roads by all vehicles. Again we are looking from the end of WWII until last year.

The oil shocks made rather less impact on the human behavior and land use components. VMT only dipped down very slightly, following each increase in price, and then resumed growth quickly, even when prices stayed high. We can see this more clearly by looking at the changes in VMT on a year on year basis.

As you can see, the effect of the Arab oil embargo was essentially gone after 1974: growth in VMT resumed at about 5% per year in the mid seventies, much as it had been in the fifties and sixties. This is despite the fact that prices did not go down again in 1974, but stayed at the $40 level ($2004) through 1978. However, 1978 caused a more profound transformation - miles only actually shrank in two years (1979 and 1980), but growth was depressed for several more years after than, and didn't reach the 5% mark again until the late eighties. It has been consistently lower than that since (which I discuss below). Anyway, the second '70s oil shock drove the point home more strongly than the events of 1973 and caused a multi-year shaving of VMT growth (but very little and brief actual reduction in the absolute level of driving).

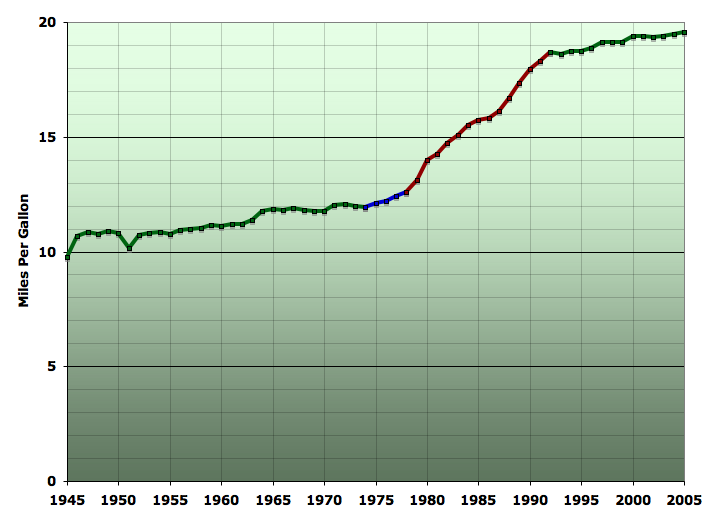

The fuel efficiency response to the oil shocks was much stronger than the VMT response. The next graph is an approximate estimate of gasoline vehicle fuel efficiency derived by taking total gasoline supplied numbers from the EIA, and dividing them into VMT statistics (corrected for non-gasoline vehicles1). Note that this is not the fuel efficiency of new vehicles supplied, but rather the achieved fuel efficiency of the entire gasoline fleet in actual use that year.

Fuel efficiency was trending up very slowly from 1945, but had only reached 12mpg by 1973. It starts up slightly faster in the blue region between 1973 and 1978, but then really starts to take off after 1978, climbing to almost 19mpg by 1992. Since then it has resumed a very slow rise, similar to the pre 1973 years. It never went down again. Thus the oil shocks clearly caused a large and permanent change in the fuel efficiency of the US vehicle fleet.

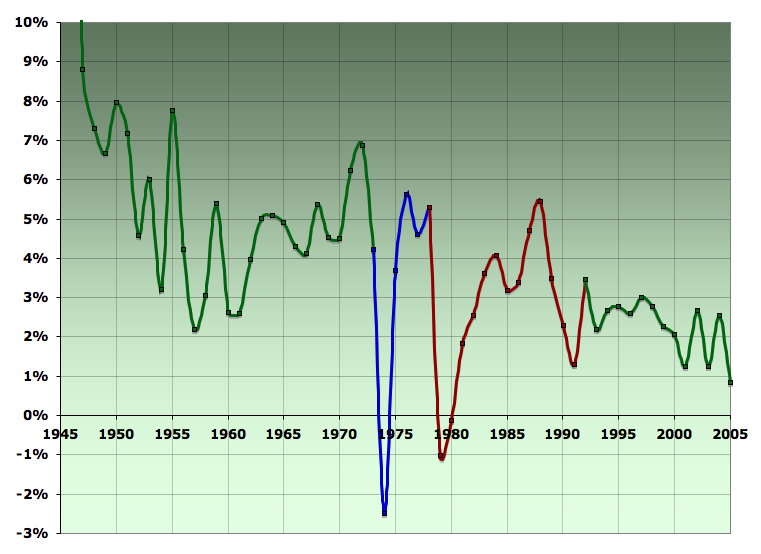

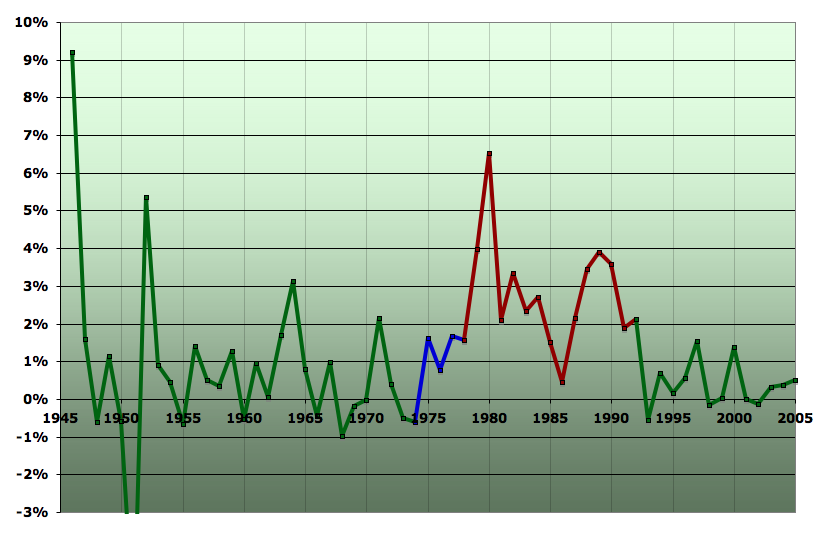

We can see this in more detail if we look at a graph of year-on-year percentage changes throughout this period:

Prior to 1973, percentage increases oscillate generally in the 0%-1% band. Overall, from 1945 to 1973, the compound annual growth rate in fuel efficiency was 0.7%/year. After 1978, increases are much higher, fluctuating mostly over 2%, and reaching a high of a 6.5% gain from 1979 to 1980. On average, from 1978 to 1992, fuel economy grow at a compound annual growth rate of 2.8%/year - a major contribution to the situation. From 1992-2005, however, progress has stalled, with average annual growth of only 0.3%/year.

One thing that struck me as very surprising is the lack of impact of the 55mph speed limit. This was adopted in 1973, and one might have expected it to make an abrupt and significant contribution to the solution. However, fuel economy increases between 1974 and 1977 were only very slightly higher than those of earlier years and it is rather hard to discern a major effect (eg a big spike up in the fuel economy growth rate in 1974 is not evident at all - there is not even a modest response until 1975). Nor is there any sign of a decline in fuel economy when the policy ended in 1995. Overall, I find very little evidence that the 55mph speed limit had much effect at all - presumably compliance was too poor for the theoretical benefits to emerge in practice.

In thinking about the post-peak future, then, it seems clear that the 2.8%/year average growth in fuel economy achieved 1978-1992 has to be taken as a lower bound on what the economy could do in response to high fuel prices. Obviously, the response faded away, but that is clearly not because we are anywhere close to the technical limits of fuel economy, but rather because the price stimulus faded away. There are 50mpg vehicles on the road now that are acceptable to at least some current consumers, and the next generation Prius (available in 2008) is rumored to achieve close to 100mpg while improving acceleration from the present version. While not everyone will drive a Prius, the mix of cars does shift towards compacts and subcompacts when oil gets expensive. And of course, the 2008 Prius is very unlikely to be the end of auto-engineer's ingenuity when sparked by high gas prices. All in all, there seems no reason to suppose that the gasoline powered fleet could not run four or five times more efficiently than the current approximately 20mpg fleet, and probably more eventually. It's just a matter of how quickly we can/will get there.

It is tempting to take the 6.5%+ annual improvement in fuel economy achieved from 1979 to 1980 as a best case for the annual improvement in fuel economy that could be achieved on a sustained basis if we really, really had to. There are some significant uncertainties however that make me uncomfortable with this. Let me outline both those uncertainties before giving my rationale for my eventual choice. With the available data, it's hard to understand in detail how the adaptation that year was achieved - it's a stunningly high figure given that in recent years only 8% of the auto fleet has been sold annually (that is sales of new cars is 8% of the size of the fleet, roughly).

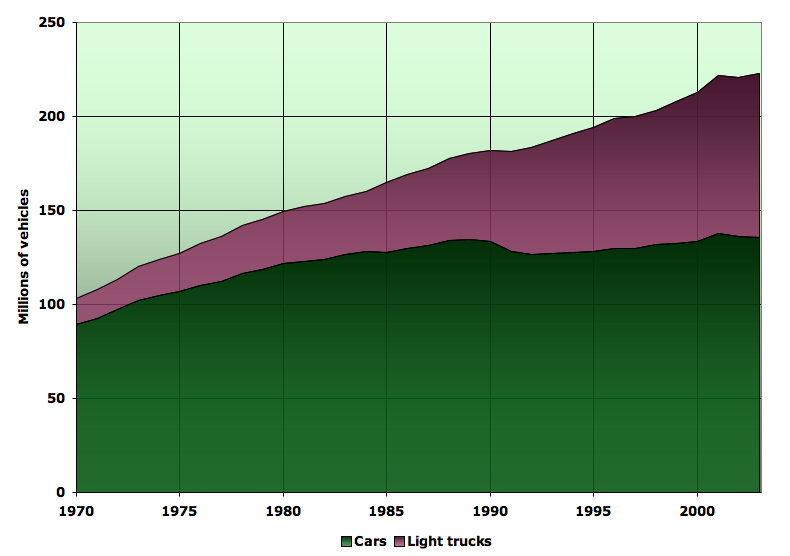

Let's review the summary data. Here's the overall size of the fleet of both cars and light trucks (ie SUVs, minivans, and pickups):

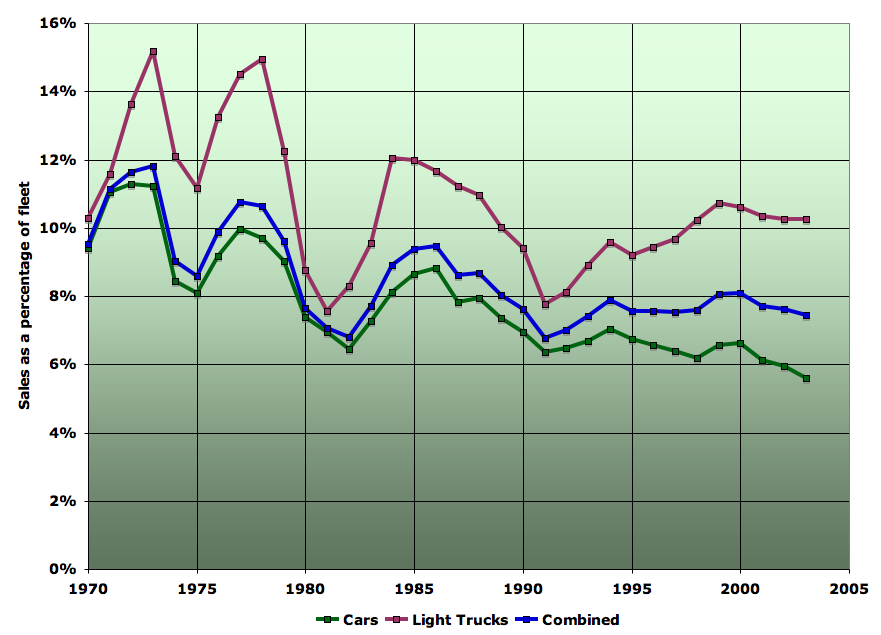

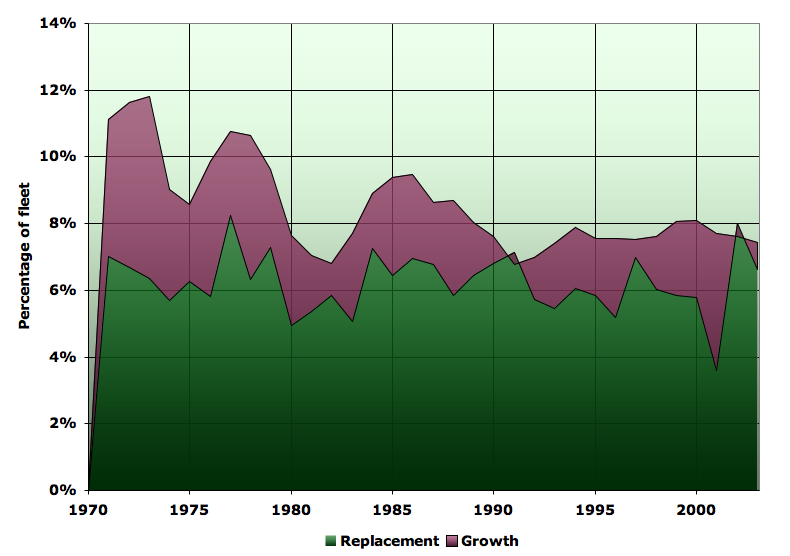

Clearly visible is the gradual secular trend towards light trucks and away from cars. The oil shocks are not a profound feature of that trend. Now, however, let's look at sales, expressed here as a percentage of the fleet size in the year of sales:

Three things stand out. Firstly, the light truck sales/fleet ratio is higher than that of automobiles, reflecting mainly the fact that the light truck fleet is growing faster. The "combined" line is closer to the car line (since there are more cars in the population). Secondly, in the past, the sales/fleet ratio was typically higher (with the combined ratio being around 10%-12%, versus the 8% in more recent years). Probably this is because cars last longer these days. Thirdly, the oil shocks are clearly visible as sharp drops of several percentage points in the sales/fleet ratio (reflecting the fact that the oil shocks triggered or worsened serious recessions, and car sales go down in recessions).

Since in 1979-1980 the sales to fleet ratio was down at around 7.5%, it's very hard to see how substitution of old vehicles with new could have given rise to a 6.5% rise in fuel economy. To get a better lock on this, we need to understand how many sales went to fleet replacement, versus fleet growth. By looking at year on year changes in fleet size, as well as sales, I came up with the following breakdown into the proportion of the fleet that gets replaced each year, and the proportion that is involved in growing the fleet:

Note that the couple of times the "growth" number went negative is because the fleet shrank slightly in those years. As you can see, the "replacement" proportion is much more stable at around 6% of the fleet (give or take a percentage point), with most of the volatility in the growth line.

Still, this makes the 6.5% fuel economy gain in 1980 all the more interesting, since only about 5-6% of the fleet was replaced in 1979 and 1980. There are two possibilities that I can think of. One is that scrappage mainly affects vehicles that are much worse than the average fuel economy, while new cars bought during an oil shock are much better than the average fuel economy. However, we know the new fuel economy stats, and there's no way to explain all the fuel economy gain this way. So perhaps there must also be internal rearrangement of the fleet. That is to say, high mileage drivers sell gas-guzzlers to low-mileage users, and/or pick the highest-mileage vehicle available to them for longer trips.

All in all, I feel that I don't understand this number well enough to assume it could be sustained. However, I note that in 1979 there was a 4% improvement in deployed fuel economy, and then again in 1989 there was a 3.9% increase. Plus several other years achieved improvents in fuel economy over 3.5%. Therefore, I feel that 4%/year is a reasonable estimate for the economy's sustained ability to improve fuel economy when it's under very great pricing pressure to do so.

Some might argue that there is a case for assuming the post peak-oil the economy will be very different and capable of much larger responses. However, I notice that the replacement rate for the vehicle fleet has been pretty stable at around 6% for several decades and in oil shocks changed only slightly (and that down, rather than up). Thus I think the case for assuming that we can improve fuel economy faster than that after peak oil is poor. (Not that it definitely couldn't happen - the uncertainties are considerable - but it seems unwise to plan on it).

In short, then, after lots of detailed analysis, my best guess for the potential size of the fuel efficiency wedge remains the same as my first SWAG of 4%/year.

To make clearer what that would look like, suppose hypothetically that we began increasing fuel economy at 4%/year starting in 2007 over 2006. Here's the picture:

Clearly, it would take sustained major pricing pressure to make people do this. However, I have also put the current nominal fuel efficiency of the current model Prius, and the rumored efficiency of the 2008 Prius on the chart. We wouldn't reach the former level as a fleet average until about 2030, and the latter level wouldn't be reached until after 2040. So clearly, there is no technical barrier whatsoever to a number of decades of 4% fuel economy growth. And that ought to be long enough to solve the large-scale plugin hybrid problem. So I'm quite willing to assume sustained 4%/year increases out past mid-century.

To achieve higher than around 4%/year gains, it seems to me that it is likely market mechanisms would not suffice. The key to going faster would be retiring more old inefficient vehicles and replacing them with new highly efficient ones. Gas taxes would be one method, but I suspect that what might be a lot more politically acceptable is something like a government tax break for people who retire an inefficient vehicle and replace it with one that's at least X% more fuel-efficient (this would create more benefit than the current hybrid tax-break, since it would encourage retirement of bad vehicles, as well as purchase of good ones). However, I cannot currently estimate how cost-effective such a program would be. A more muscular approach would be to create sunset dates for low fuel-efficiency vehicles enforced through the existing smog-testing infrastructure. All vehicles that failed the current fuel economy bar would be forcibly retired, and the bar would be raised each year. It would require considerable political will to create the conditions under which such legislation would be passed.

Next, I'd like to make some more analysis of what is the business-as-usual case from which one should be deducting this as a wedge. For this, we need to go back to the VMT statistics. I would like to now break VMT down into a product of two factors, both growing. The first is the US population, and the second is the VMT/capita.

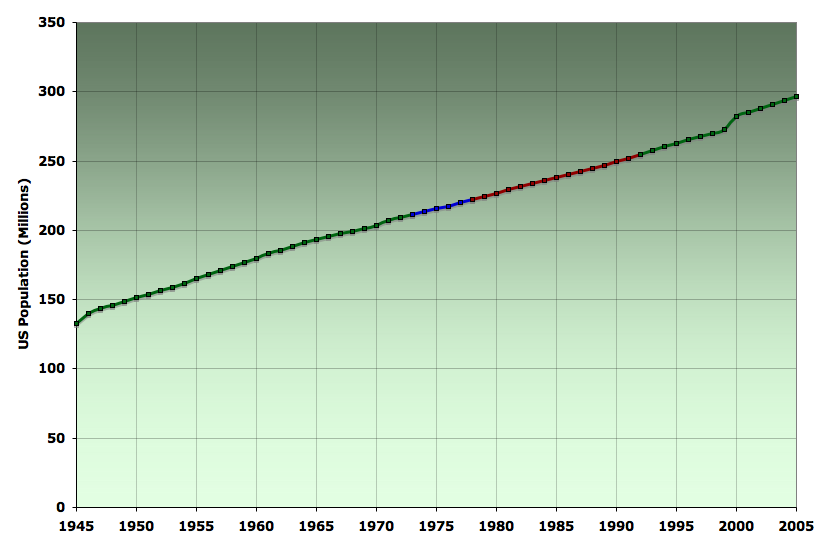

Let's take population first. It has the merit of being very boring in its behavior:

As you can see, with the exception of a couple of anomalies, most notably in 2000, the growth has been very smooth and linear. I have not been able to track down what happened in 2000, but my guess is that there was some change in the Census Bureau's estimation methodology, rather than an actual sudden step in population. Henceforth I will treat that year as an outlier to be ignored.

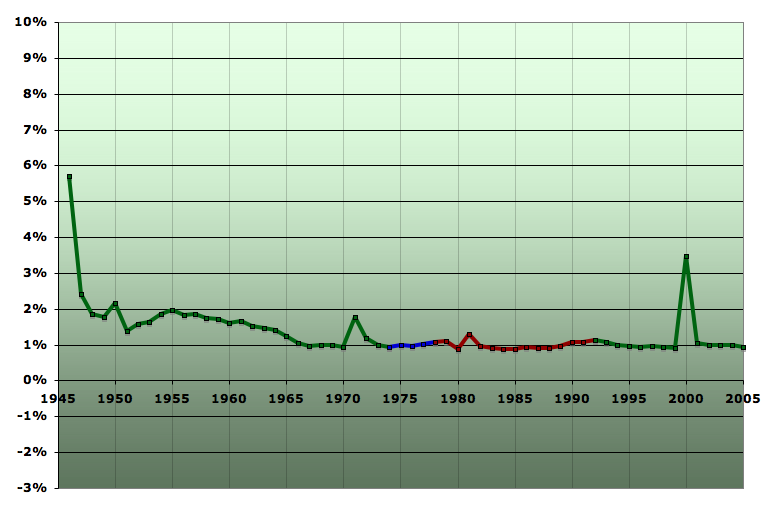

We can get a more precise sense of past growth by looking at the year-on-prior-year percentage change in population.

Population growth dropped to 1%/year about forty years ago, and has been very stable there ever since. The 1970s oil shocks had no impact at all on population growth, and nor has much of anything else that's happened since about 1965. It seems, then, that any projection other than "about 1%/year" going forward would be rather hard to justify. The demographers at the Census Bureau believe it will drop gradually to about 0.8%/year over coming decades, but the difference seems small enough that I will stick with the numerically more convenient 1%.

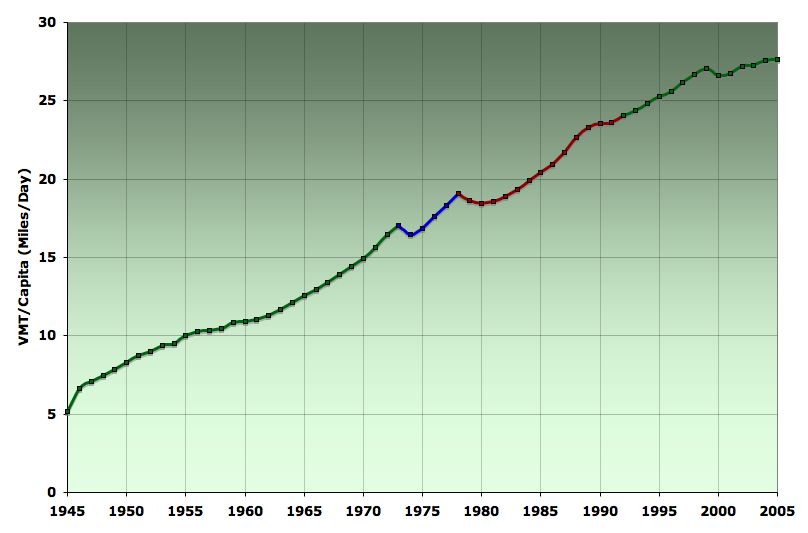

If we now divide the population out of the VMT growth, we get the following graph for VMT per person (this is all vehicle miles by all vehicles on any road in the US, divided by every man, woman, mewling infant, etc).

Back in the late 40s, we managed on less than 10 miles of daily vehicle movement per person. Now it's up over 25 miles per person. It was climbing until the last year when high oil prices (presumably) have caused it to level out. The oil shocks in the 1970s loom a little larger in the per-capita signal than in the overall total (not surprising in light of the fact that population growth was completely unpeturbed by oil shocks, so all the effect on VMT comes from the per-capita factor, rather than the population multiplier). Let's look more closely at the year-to-year changes:

Hmmm. The oil shocks are very visible, but as we noted before, did not have very long-lived effects on VMT growth. The 73 shock (which apparently mostly just primed people to respond to the 79 shock), causes a dip in the curve that is really over by 1975. However, the 79 shock takes several years, to overcome, with VMT/capita growth not back to normal until 1983.

However, there's another interesting and important thing expressed in this picture, and that is that VMT per capita growth was significantly lower in the 1990s than it was in the 1980s, and also in the 1950s and 1960s. To quantify the issue, here are the compound annual growth rates for a couple of regions of the graph:

| Years | Growth |

| 1950-1973 | 3.2%/yr |

| 1973-1983 | 1.7%/yr |

| 1983-1993 | 2.3%/yr |

| 1993-2003 | 1.1%/yr |

What's going on here? The growth in VMT/capita was lower in the 90s even than in the period 1973-1983 when there were oil shocks. This matters because we want to know if this decline would continue in the future even if we had no oil supply/carbon emission problems, or if it would rebound.

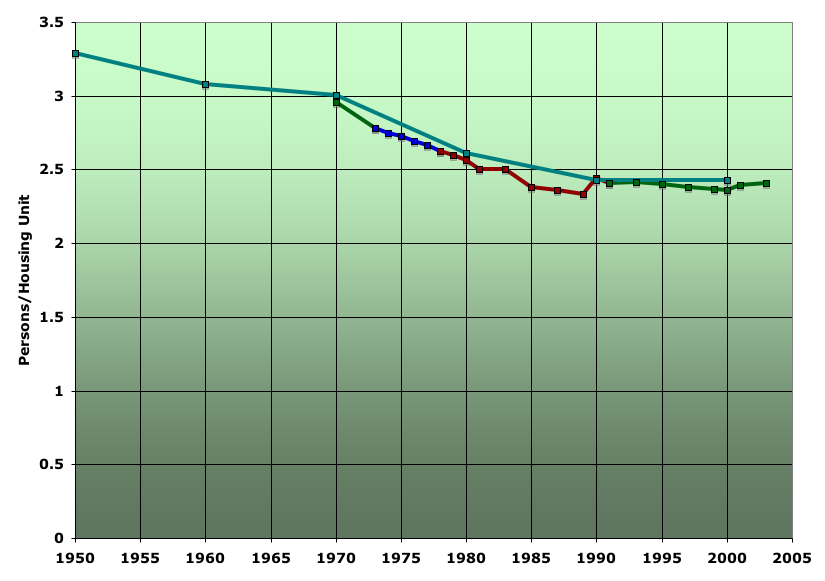

Here is likely one piece of the explanation. The next graph shows the ratio of people to housing units in the US. This is, roughly, the average number of people in a household, but also incorporates the effects of empty units, vacation homes, etc:

As you can see, people/unit declined steadily from the end of the second world war through the end of the 1980s. This probably primarily reflects the increasing trend towards divorce and the demise of the extended family as a living unit. However, it also no doubt got an assist from more vacation homes. Likely, demographic factors also played a role (from 1945 through much of the 1960s, the baby boomers were kids at home, and after that they moved out). Obviously, to the extent people are spreading out into more housing units, they are going to tend to use more VMT each, though it's not a linear matter (Eg consider a couple with two kids who divorce and get 50% custody. The two kids still only need to be taken to school once each. However, the two small households are likely to make nearly twice as many grocery runs as the one big household. The number of jobs held is likely to go up also, on average).

In the 1990s, people/unit stabilized and has been pretty much flat ever since. This could have a lot to do with the slowing in the growth of VMT/capita. To the extent this is a permanent social change, then VMT/capita might continue to grow at a lower rate in the future (even in the absence of oil/carbon constraints). Another possibility to consider is that people/household might actually start to go up again in the future, especially in the face of a tighter economy; adult children might be slower to leave home, aging relatives might be more likely to live with family as nursing home expenses continue to escalate, divorce may seem less economically feasible, etc. However, given that the seventies oil shocks caused no densification whatsoever, it is probably unrealistic to expect anything more than an extremely gradual rise.

Besides people/unit, another likely factor in the 1990s is congestion. As the FHWA describes the matter:

During this period, growth in highway and mass transit systems in the United States did not expand at the same pace as the growth in travel demand. In the case of highways, total mileage in lane miles increased only 0.2 percent nationally during the entire period, from 8.11 million miles in 1992 to 8.25 million miles in 2000. As a result, travel per lane mile increased on all systems and, in particular, at faster rates on rural routes. While most travel now occurs in urban areas, approximately 77 percent of lane miles are on rural, local-owned highways.Without getting into the debate over whether this reflects a lack of political will to build highways, or the impossibility of solving the problem by building more highways, the effect was that congestion went up:

Presumably, this has a deterrent effect on traveling and has contributed to the slower growth in VMT/capita.

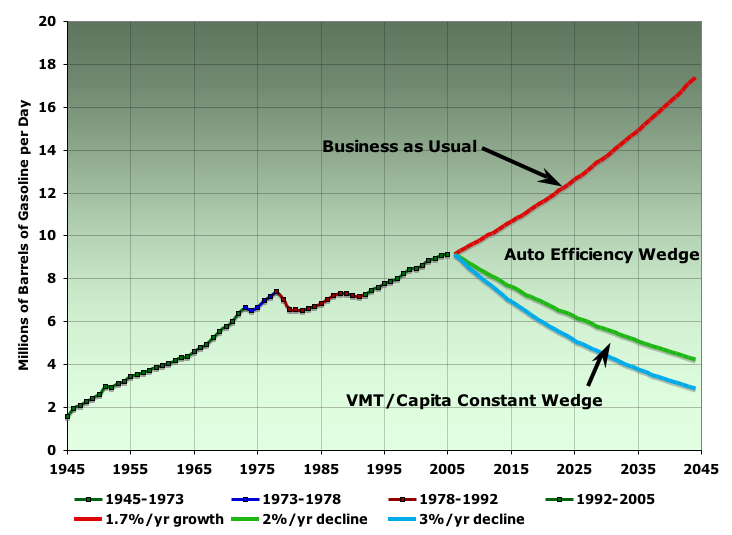

For my purposes here, I am going to assume that "business-as-usual" going forward, in the absence of energy issues, would have been continued 1%/year growth in VMT/capita (cf the 1.1%/yr growth in this quantity from 1993-2003). Combining this with the 1%/yr growth in population, we would anticipate 2%/year growth in VMT. Since, as above, fuel economy has been increasing at 0.3%/year since 1992, our overall business-as-usual in gasoline usage would be 1.7%/year growth.

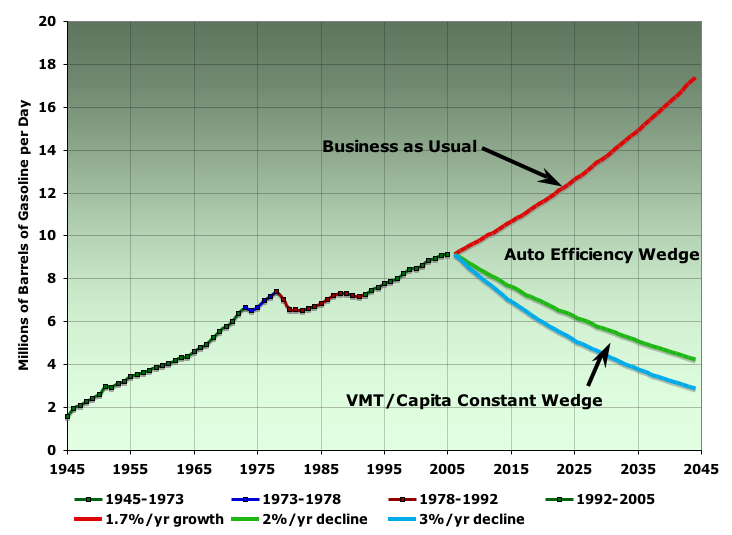

This next graph shows that 1.7% growth in gasoline usage out through 2045 (the end of my expected lifetime :-). I also show what would happen if VMT growth was identical, but fuel economy increases by 4%/year instead of only 0.3%/year.

As you can see, it makes an enormously dramatic difference. The most aggressive scenario on the graph shows what would happen if, in addition to improving fuel economy by 4%/year, we also could hold VMT/capita constant from here on out (instead of it growing at 1%/year as under the business as usual scenario). That's better still, but stabilizing VMT/capita is not nearly as useful as getting fuel economy moving upward as fast as possible.

Finally, to aid your intuition for growth and decline processes a little further, my last graph shows the business as usual and 3% decline scenarios with two different ones in-between. The 0.7%/year growth is what you'd get if you just capped VMT/capita growth but only continued the recent history of 0.3% fuel efficiency. The 1.1%/year decline would come from business-as-usual VMT/capita growth together with 2.8%/year annual increases in fuel efficiency (the same as was actually achieved on average from 1978 to 1992).

Footnotes

- The approximation comes in that it is not straightforward to allocate vehicle miles between gasoline vehicles and diesel vehicles from the available statistics. My approach from 1966 on is to assume that all passenger cars and all "two axle four wheel trucks" run on gasoline, and larger trucks and buses run on other fuels. Prior to 1996, the "two axle four wheel" trucks are not broken out from other trucks, and I linearly interpolated that post 1966 data backward to estimate the proportion of larger trucks. My procedure is unlikely to be perfect (some cars and light trucks run on diesel and some larger trucks burn gasoline), but the error is probably modest, and probably fairly stable over time. In recent years, FHWA has made their own estimate of deployed fleet fuel economy via methods they don't document enough to reproduce. Their estimates are about 1/2mpg higher than mine. Theirs may well be more accurate, but are not available throughout the period of interest.

- There is some uncertainty in the allocation of this quantities between neighbouring years, since it is not clear whether the fleet totals in the TEDB are for the beginning or end of the year, or an average. Here it is assumed that they are end of the year totals.

The conventional wisdom, reinforced by Yergin et al, is that we can continue with an exponential increase in imports for years to come.

As I said before, IMO we are now facing a collision between the expectation of exponentially increasing imports and the new reality of exponentially declining exports--led by the Saudi's estimated 13% decline in exports from 12/05 to 12/06.

For US imports to just stay constant, we have to reduce our consumption by a volume of oil that is equal to our annual volumetric decline in production. And we have to reduce our consumption by the same amount--matching domestic decline--every year going forward, just to keep imports constant. Note the key challenge here--this would only keep our imports flat year over year, while world net export capacity is now declining (whether this trend will be reversed is the key question; I think not).

It sounds like your saying we could have a price shock as early as next year ?

The Saudis have reportedly told some Asian refiners that they can only have 92% of the crude in January that they wanted to buy, down from 95% in December. Voluntary? Right.

IMO, the export crisis is upon us.

From my reading the data on gasoline usage, recessions don't even show up on fuel consumption so for now I don't think anything outside a world wide depression will cause a significant drop in fuel usage.

Hmm I figured a spike late next summer based on to many negative factors causing a run on the market I did not consider any actual shortages for quite a bit longer 2009 at the earliest.

My opinion is still only a price spike in 2007 since I think KSA is filling storage and we still have the SPR that can be drawn down. Plus I think they have idled some production it may be heavy oil but I still think its happened.

So if you consider these factors we won't see shortages in 2007 and probably not 2008. 2009 is looking like a really bad year maybe 2008 but I think we will squeeze through 2007 with just one price spike and limp into 2008 with oil under 100.

Of course this depends on the decline rates of the big fields but I'd have to guess we have one more year at least where excess capacity and stockpiles will prevent outright shortages and all we see are price swings with on big spike.

We just have to wait and see what KSA does when oil passes 70. If their production does not come back up for 6 months or more we know the party is over. So I guess we will know exactly where the world is at in 2007.

One thing about them claiming cuts and proclaiming a floor at 60 is it will soon be obvious where KSA is at as prices move well above this floor price.

If KSA says they are now comfortable with 70 next year ....

¿Maybe a reduction on available fuel?

I do not care what some vice president says about something being non negotiable. If something gets too expensive, people will cut down. Witness medical insurance.

I did not say it would be pretty.

I dunno I thought the same the facts seem to indicate that economic recession at least on the scale we are used to does not have a major impact on fuel usage. If you think about it for modern countries your talking about a real change of maybe 3-4% in the economy from slightly positive to slightly negative. Fuel usage would be a % of this so say at worst 1% ?

So you would have to reach depression level economic slow downs to have a significant impact on oil. Put it this way to reduce overall oil demand by say 5% your probably talking a 20% reduction in economic activity. Note a lot of the economy is powered by electricity coal/NG so oil prices does not have a direct impact on the core economy. If you can find evidence that this is wrong please show me.

Now with that said shortages on the other hand especially chronic ones are a different ball game altogether and simple conservation probably won't solve those types of problems.

Whew, that was easy.

I still wonder if prolonged and worsening fuel shortages will, over time, change the value map of real estate. I would anticipate that given high enough fuel prices, locations proximate to both jobs and goods and services will start to increase in value vis a vis locations that require longer travel distances to reach same. I wonder, however, how high gas prices would have to get for this to be the case, as they represent only one component of the cost of using an automobile for travel.

Regardless, my city is seeing a growing number of development applications involving mixed-use formats, intensification of older centers (not just the downtown, but around malls) and infill in established neighborhoods, all of which increase proximity. The market is already trending to some extent in this direction, even with current low prices.

I suggest that you revisit this conclusion one year from now.

IMO, the decline in net oil exports is going to hit so hard and so fast that we will have no choice but to abandon large swaths of Suburbia.

IMO, this will be virtually the only "growth" areas that we will see--especially along mass transit lines.

There would then be a sharp decrease in the use of petroleum and a subsequent glut in supplies.

IMO, this makes no sense - the peak/plateau/whatever you believe will happen will play out much slower than this.

You are absolutely correct about aggregate world oil production, which I predict will show a net decline rate of about 2% per year going forward.

However, I think that you are absolutely wrong about net oil exports. For example, Saudi Arabia's production is down by about 7% from 12/05 to 12/06, but I estimate that their exports are down by 13% from 12/05 to 12/06.

Your "conventional wisdom" view is why, IMO, the net export crisis is going to hit so hard and so fast. We simply assume a continued exponential increase in imports, while the mathematical models--correctly so far--are predicting rapid declines in net export capacity.

I was roundly criticized in January for predicting that Saudi Arabia and Russia would join Norway in showing lower exports this year. We can argue "why," but the Saudi and Russian governments have both now admitted to lower exports.

If you can believe the information about the looming nat. gas shortages (which is being reported by more than one source)and estimates are that we need to import 1.5x our current oil to make up the difference, we are in for a world of hurt.

SEATTLE-

Had 62 people in the hospitals who had carbon monoxide poisoning, trying to stay warm in the recient power outage. Sadly, we may get Kunstlers die off easier than we think.

BTW currently in day 6 of power outage here in NW Oregon. Running generator 24 hrs a day keeping greenhouses warm...can you say expensive...

But we don't know what might happen after the peak. We are just assuming that because the US for example has undergone a gentle descent after it peaked that this effect will apply to the world situation. Forgetting that the US having been geopolitically and economically stable, and almost completely accessible to new drilling and further exploration up until now. I fear the world scene will, within a short space of time, be anything but orderly to make for a long-term gentle decline. Especially when you consider the knock-on effects that unsustainable economic practices and population growth is, or soon shall be, delivering to us, one after the other.

Yes but it will take time for all this to unwind. In a earlier post I mentioned the use of the SPR to calm markets etc.

So the first reaction is its a spike and we should see a small rise in exports as any excess capacity is brought online.

So I still think overall its just a price spike next year with a new floor price at 70-80. It just takes time for all this to unravel I'm guessing a year or two say 2008-2009.

And of course you have even more demand destruction in the third and now second world lowering usage. And you might get just a little bit of economizing hear in the US as we did during the last crisis.

I could bring in more factors but they all point to a price spike and drop next year with SHTF type stuff happening later. Two or three years is not a lot of time IMHO.

Looking at how our car fleet changes over time its pretty obvious we will be caught between a rock and a hard place well before we could adjust to peak oil.

None of those allow us enough time to make sufficient changes, and the impacts will be be uneven for sure, harder in poorer areas or more debt burdened areas.

IMO, it won't play out over 15 or 20 years. And any of the other possibilities above are too fast for a soft landing.

========It's all about population!

I agree I don't see how we have time now for the slow conversion Stuart is proposing. Its realistc.

On the same hand the world will not end tomorrow. Even if oil went to 150-200 a lot of people can still afford to drive and car pooling and public transportation can help those that can't. And of course fuel efficient cars would be purchased by those that can afford them. At the minimum you would see America approach Europe/Japan in efficiency.

The only thing I see ending is Americas crazy suburban life style and outdated work conditions i.e everyone doing 9-5.

So at least in America the big looser is the suburban lifestyle and the ponzi scheme supporting it will unravel.

For example Stuart is not considering the cost of roads under expensive oil conditions. Suburbia has a lot of hidden costs.

Now with all this said these changes would be occurring during the first five years of peak oil but I can't see how we will be changing fast enough to prevent repeated shocks to our country and the result creation of a slum class common throughout our world.

Now of course third-second world countries would suffer a lot more and political instability their is probably a bigger issue along with the creation of our own internal third world country.

Dyslexia and spell checker colliding sorry

Funny though :)

I agree with your land export model. However, I don't see a rapid abandonment of suburbia, only because people have to have someplace to live.

Let's assume some people can no longer afford to drive and then lose their jobs. (or they just lose their jobs). Sometime in the near future (6-12 months), they lose their suburban home. Most shelters are in the cities, so they head for the cities. Now, the cities become home for large numbers of homeless former suburbanites. Part of the growth of the cities has been their ability to "clean up" downtown, moving trash and homeless people off the streets so the wealthy could have a pleasant living experience. What happens to that experience when it is spent stepping over the homeless?

Again, figuring that some people lose their suburban homes. The banks or mortgage companies or individuals who own mortgage backed securities, now own the houses. What are they going to do with them? After accumulating huge numbers of houses, who will they sell them to and when do they stop gathering them in? Do they write them down and accept lower payments? I don't know.

Do the remaining suburbanites gather politically around homesteading relief to save the American dream?

Let's say the US cannot import as much oil as before and domestic production is falling? How does the oil get allocated? Yes, defense and policing get theirs. But eventually, there is a market for what's left. So the price rises and some folks don't get any. Who loses out first?

In most cases, the poor with gas guzzlers get hit first. The price rise eats into their existence until they have to drive less. They don't have the resources to buy a prius, so they are screwed. They also work physical jobs which cannot be relegated to telecommuting, so they have to go to work. They give up their car and black-market taxi service begins, kind of underground car-pooling. Some guy with a mini-van will stop by your block and you can get a ride to a location close to work. Poor folks already use cabs, some legally and some not. This helps reduce vehicle miles traveled per capita and fuel needed.

The folks in suburbia get hit too, just differently. For some, the increase in fuel costs forces a reduction in miles traveled. For some it doesn't reduce miles traveled, but reduces the discretionary funds available for flat-screen TVs, etc. Again, for some, it puts them over the top and they lose their house.

I wonder how the age of a suburb will matter. Older houses cost more to heat and cool. Older houses have older residents who, may be more apt to leave the large house since their kids are gone anyway. On the other hand, older houses with older residents are already paid for and don't face peril from missed mortgage payments.

Let's assume that the suburbs collapse and everyone wants to move into renovated or new urban housing. If they lose their shirts on their suburban home, where do they get the money to buy the urban home? Builders don't have to build, they'll just lay off their workers.

I think suburban growth is going to stop. However, the only way people don't live in the suburbs is if we reduce the population or we build a ton of new housing. I think our debt burden limits the latter.

I agree suburban asset values will get hammered. I just don't know where folks would go.

Sure, foreclosures and homelessness will rise, even sky rocket initially. But isn't the system itself vulnerable to failure as to eventually preclude the possibility of widespread eviction/foreclosures carried out with cooperation of a fully functioning local government? I've got to think there is a break point in there somewhere. Just dont know what level it is.

They will buy a Prius, of course. There will be no recession, only a dying breed of they-never-learn managers at Ford and GM and record sales at Honda and Toyota.

I think the general rule would be more like, "people want the roomiest, highest status, best (perceived) quality product they can afford." I don't think we can leave out the "they can afford" part of the rule.

Yes, people still believe in the better school district myth. The factors which most effect student performance are the education level of the parents and the size of the school. The smaller the school the better the students do.

A school district is considered better only because it has fewer black kids. It is just pure racism that makes people look for "better" schools.

I know several people, including myself which have purposefully selected a home that is closer to work. A lot of them site the steady rise of gas prices as being a motivator along with the frustration of losing 2 extra hours of their day doing a long commute.

Its anecdoctal, but I think changes are begininning to occur, and I think another summer of some price discomfort will push more change. A slow squeeze I think ultimately may be the best outcome in providing motivation for change, as well as providing time for change.

Other people have two jobs or they change jobs frequently.

In general, I think the planning/land-use stuff matters over a long timeframe. There's not much you guys can do to make a difference over a decade or two, but you are critical over the century timescale. The land-use approach of the last 50 years is going to cause us problems for a very long time.

With regards to changing land use, here's some speculation as to how it might occur quicker than you think. The U.S. is experiencing significant population growth, and much of that is occurring in sunbelt cities like mine, which is adding about 5,500 units and 12,000 people per year, mostly in a suburban pattern. Even if no existing housing is abandoned, where these new people end up could have a dramatic impact in densifying established neighborhoods and corridors.

If the value map does change significantly, all manner of passed over sites will start to look attractive. One large source of underutilized land can be found in existing shopping strips with oversized parking fields and generally inefficient layouts. As income gets diverted from retail shopping to energy costs, many of these may become fully or partially abandoned. Infill development on these lands would put additional density not only close to shopping and jobs, but also along corridors that one day might see increased transit (I know, I read the earlier posts, but I think peok oil will bring at least some increased demand for transit).

Will people move into multifamily units in redeveloped shopping malls and strips? In fact, its already happening. I predict in many parts of the country, the barrier will be regulatory, not market-derived, as people cling to existing development patterns. Hopefully that obstacle will fade away when the seriousness of the situation becomes apparent.

http://www.vividpicture.net/documents/sustainable_food_system.html

If your talking about putting up 50 story towers then basically anywhere outside the heart of the largest cities is viable for redevelopment.

In all its just a matter of when it becomes economically viable. Once it does I see no reason that the value of our current properties and suburbia won't fall. It happened after WWII and it can happen again. Once you have livable cities in the US I think the tide will turn quite rapidly.

Also consider that the recent housing boom coupled with the retirement of the baby boomers will basically wipe-out demand for suburban housing for the next 10 years at least if not forever.

A lot of people who bought homes over the last 5 years will probably loose them over the next several years. A lot of baby boomers will opt to move out of their old suburban house in exchange for condos which will be cheap because of the initial glut and they can still make a decent profit of their home. So you have a influx of renters and condo buyers that will be interested in living close to work. The condo won't go for anywhere near the price that they are at now but their will be demand once the price drops back down to something reasonable.

Remember you just need enough to reach critical density once the number of people living in town grows large enough you will get back your shops/restaurants etc causing more growth.

If it goes like I think it will with suburban home prices falling every year and growth moving towards the cities powered by people that are not in the housing market either because they are retired or lost a home it will continue as apartments/condos actually become more desirable because of oil shocks.

So once you add the above with oil price issues you have a suburban areas never recovering and thus no reason to try and maintain them. Remember suburban regions are very sensitive to what I call loss of face. Once you get enough empty homes and rentals that are not maintained value drops like a rock resulting in further flight into renewed downtown areas.

Finally we have to build something in the US and it looks like suburban houses won't be viable and it is possible to build nice high density apartments/condos at reasonable prices so I think the builders will build them. They basically have to build something and as long is their is demand high rise condos/apartments are simply cheaper to build and thus cheaper to buy.

This is the same idea that Le Corbusier proposed in 1922-25. He called it "The Radiant City" and it became known as the "towers in the park" model.

Just one thing -- Le Corbusier didn't anticipate the requirements of mass automobile ownership. So "towers in the park" became "towers in the parking lot" connected by large freeways -- see Houston, etc.

Even in a car-free society, isolated towers incur prohibitive costs of stringing infrastructure out to distant locations -- water, sewer, gas & electric, roadways -- and the prohibitive costs of servicing that sprawling infrastructure.

Singapore has this model they have a lot of parks and open spaces in the city. Also a lot of European cities contain parks. As far as infrastructure goes. I'd assume the main thing would be rail. Cars would be controlled via massive fees for limited parking along with huge use taxes esp city entrance fees etc.

Quality of life is vastly improved in the city with the addition of some green space. Next the assumption is these towers would not be on the edge of the city but say within 5 miles of the city center. That's a lot of land but you still can have density high enough to keep supporting services cost low. I think one thing that has prevented a lot of Americans from moving into the city is the lack of nice parks in American cities even if its private parks. And they don't have to be large.

In any case the isolated towers can themselves form part of mini cities as we see happening in Japan for example.

A huge amount of literature exists on how to make dense cities that are both easy to walk pleasant and beautiful.

Huge highways, not pedestrian friendly at all.

In fact, aren't walking tours very popular?

The consumeristic focus of Singaporean society is a bit disturbing, but the quality of life is suprisingly high, given the extreme population density

The simple reason being government taxes and quota. For example, a Honda Civic Hybrid costs slightly more than USD50,000 and a Toyota Prius would cost USD55,000.

98 Octane gasoline costs around USD4.40 per gallon before loyalty discount.

If you drive through the congested roads at peak hours, you might have to pay up to USD6 per day.

:-)

sounds like you haven't seen much.

within 10 minutes walk i can access 3 supermarkets, library, the church, shops, 2 out door markets, food places (macdonalds too), banks, post office. very pedestrian friendly but also high density living. point google earth. the resolution is sufficiently good to make out the high density places.

i would certainly love to have a house with a two car garage like i used to live while in the usa - cheap cars, cheap petrol, beautiful outdoors. but come crunch time i foresee an urban enviroment being a comparatively advantageous place to be in terms of transport cost and access to amenities.

to give you an idea. not many people own cars ( cars are around 3 times what you'd pay and petrol is probably double. not only that, you only have the right to drive the car you bought for 10 years, after that it goes to the scrap yard or has to be reexported out of the country). public transport by taxi, bus or subway is cheap by comparison to cars. round trip cost to work about $1.

finally its just a matter of adjusting to a different environment. i'm sure americans will be able to do that when the time comes. eg i've got a colleague from LA whose been here for 10 years and only takes public transport. he can't tolerate the commute by car.

Back at university, we got a kick out of the landing strips and helipads on top of the buildings.

Another problem is that while Corb's buildings were designed around natural light and ventilation, our blocks depend on mechanical ventilation and artificial light.

With the expected decline in natural gas, and the problems in importing it, we need to plan as if at least parts of the country will be seeing frequent power outages in the next few years.

Look... no large city will work at all with intermittent power supply. And no large city will ever have intermittent power supply. GW non withstanding we can build any number of coal fired power plants. The coal is there. But so are the sunlight and the wind. The choice is not between energy and no energy. It is between dirty energy and clean energy.

Barring a local surplus in construction and electrical energy sources, I don't see this a viable option, even if it dramatically reduces VMT

Let's do the math: 1 person weighing 200lbs has to be moved to the 50th floor. The potential energy is W=m*g*h=100kg*10m/s^2*150m=150kJ. You do that ten times a day, you need 1500kJ. 1kWh is 3600kJ, i.e. the elevator needs 0.4kWh/person/day. Electricity consumption in the US is a whopping 11000kWh/year/capita or 30kWh/day. In other words, the elevator to the 50th floor adds at best 1.3% to an inhabitants electricity consumption. You get similar numbers for pumping water.

On the other hand, an everage citizen living in a place with tall apartment buildings like in Singapore takes the bus or train to work, i.e. we save the gas for the car!

The bigger problem I see is in their constrution. Towers require significant quantities of steel and concrete. Both are very energy intensive to manufacture and transport. Given a severe enough shortage of transportation and manufacturing energy (oil and natural gas) we simply aren't going to be able to continue to manufacture huge amounts of both to build skyscrapers.

Small structures on the other hand will remain relatively easy to construct in comparison

In other words: reality proves you wrong. Electricity use in the city is not the problem. And the solution to the mentioned blackouts in case of an energy emergency (which will not happen) would be simple: the federal government will turn off the lights in the countryside where it will not lead to riots etc. and keep them on in the city where any breakdown of infrastructure would be a major catastrophy. It is as simple as that...

By the way... if you come out to the West, I will show you all the empty roof space we have. We drive around for an hour and I will point out enough roof area to you to produce several GW peak... and close to the whole energy consumption of the place on average.

:-)

I'm a planner and have been involved in energy planning for some time (worked for utility, then local government). The folks responsible for keeping the lights on that I talked to do not inspire confidence over the long haul absent a wholesale change in political priorities.

As for my construction related concerns, you havent addressed them. How are we going to build these structures in the future? The ones we have now, they represent energetic investments already paid for and as long as the lights stay on, a great way to minimize overall energy consumption (esp transportation consumption). But going forward--I dont know if it will pencil out.

I suspect that after peak oil, we will see very few new units constructed. Instead, we will see more people moving together into existing housing stock, because of the high cost of heating and cooling space and the high cost of transportation. Some units that are in undesirable locations will be left vacant - or perhaps dismantled for replacement parts for other homes.

Once peak oil is known, I expect the world will change dramatically. The availability of loans for building apartments and for purchasing houses will disappear, because lenders will realize they have little chance of getting their money back. The monetary system as we know it may not continue, or there may be hyperinflation.

Governments will stop building new roads, and may need to cut back on the amount of roads that they can continue to maintain, because of the lack of asphalt.

After the first year or two, I think declines in the amount of available fuel will be much larger than Stuart uses in his examples, for a lot of reasons. A few of these include

1 . Exporting countries will tend to satisfy their needs first, leaving less for export.

This seems to imply that "after peak" prices will reach out of bounds, and not fall back as a result of (a) efficiency, (b) conservation, or (c) economic contraction.

From "cheap" to "too expensive" in one great leap?

Take transportation. China, it appears at the moment, is well situated to absorb an increasing proportion of total liquids production, and at a higher price than they are currently paying. North America, on the other hand, appears only to have the conservation option open, especially as productivity seems set to fall in any case, as the quality of our energy mix declines. Are there efficiencies which we can achieve which would allow us to outstrip the loss of productivity implicit in a poorer energy mix? Are these and or other efficiencies only go to be available to us?

With all its problems, our transportation system is very economically efficient. As for externalities, while we pay for congestion, we manage to share the cost of climate change. The marginal barrel of oil is not doing much to improve the transportation component of our labour market, of our production markets, our distribution markets or our consumption markets. But additional oil can make huge contributions to the productivity of all these markets in China. It has been doing so ever since China adopted the market system. They are turning their oil imports into profits, while US imports, on a wide margin, are converted into debt.

Unable to put the marginal barrel of oil to work as productively as can occur in China (and elsewhere), we will not be able to compete on price. It's simply irrelevant how many dollars we can print. Real purchasing power has to be earned. So, forcibly we will need to conserve.

It is far from evident that even the most aggressive gains in efficiency will allow us to increase our economic productivity. I expect we will become less productive, per capita. Done properly, it's an attractive option.

No one with any strong grounding in oil production (and "large project") data has called an abrupt and steep drop.

The recurring theme is "undulating plateau" with later, consistent year-over-year declines coming some time post-peak.

Europe has grown into a large EU with better geographic access to oil and natural gas than North America. Its export markets have become less dependent on the US to the extent that Germany's exports amount to only 8.8% of total exports. Europe also presents a significant growing market for China. Even though Europe will remain subject to the usual manipulations by commodity exporting nations, there is good reason to believe adjustments can be made over the long term.

It may transpire that the economic block of "the old world" can very well go it alone. It looks as if South America is positioning itself to go it alone as well.

Here in North America we talk of significantly rising prices in the oil market over the past few years. But relative to the Euro, the increases have been fairly moderate. That may not be a coincidence.

North America finds itself in a somewhat awkward position when compared to Europe. The US current account along with significant other sectors of the economy is terribly out of balance. While it still has as strong an export market as Europe, it is heavily weighted towards services as opposed to goods, and its imports are something on an order of magnitude greater relative to other major economies.

North America is facing a looming natural gas problem that doesn't appear to be getting sufficient focus. A tipping point problem I'm sure. The market for LNG has not been liberalized and probably will not be; the infrastructure for LNG will likely grow far too slowly to meet shortfalls; and the US only owns twelve ships. In some sense, it isn't the natural gas that is stranded, it is North America. North America could soon be living off the kindness of strangers.

These differences may combine to cause significant differences in the relative price of oil between Europe and North America. Oil producers are clearly not going to give their oil away, we all can agree on that. But oil may remain reasonably affordable in Euro terms while it becomes very dear in Dollar terms. Economics and politics will determine how that plays out with oil and natural gas playing supporting the supporting role as "The Spoiler."

Between world wide peak oil, and North American peak debt, and peak natural gas, the undulating plateau period is likely have significantly different impacts on the two regions, particularly as it effects the relative affordability, and even access to, fossil fuels.

Could it be that life could turn out to be like a giant game of Monopoly and North America, in spite of its recent significant lead, could find itself out of the game?

We are trading scenarios, and possible worlds, without knowing which one of them (if any we name!) will ever shake out.

Returning to your post ... I think we are waiting for the shoe to drop. We want to know what the response will be if/when an actual oil or gas shortage becomes apparent.

National Geographic reminded me that 1967's gas prices adjust to $2.00/gal in 2005 dollars.

We haven't really hit the break point. We are trading these scenarios based on indirect signals. This is inductive reasoning, and often only weak induction at that.

I definitly agree with you that the effects of Peak Oil can not be evaluated continent by continent, or even country by country. It's my opinion that the globalization of the world markets will peak with peak oil, at which point we will begin a long slow shift back to regional and even local scales of economy.

I personally don't buy into the theory of the AMERO. If anything I think there will be a fractalization of the current large countries by geographical regions. Certainly if the value of the federal dollar weakens considerably I expect the individual states to become a lot more self governing.

Let me tell you something: start using what you have efficiently and you can kick European and Chinese ass. Keep wasting like in the past and you will be left in the dust like every other egotist mirred in his self-pity.

However, I agree with your observation that resources have been wasted or used inefficiently.

For what is worth, I'm from a nation that is a net energy exporter, but I imagine we will continue to sink or swim with the US. I can't imagine us pulling the plug on them any time soon.

I think I got mostly upset about the sentence:

"Europe has grown into a large EU with better geographic access to oil and natural gas than North America."

The growth of the EU is hardly a plus. It has become a lot less managable and most of the new EU countries will need two or three decades to get up to average EU level. Few of them have essential geological resources and most of them come with vast unemployed labor forces who are entering the "wealthy labor markets" of the western states, thus creating a lot of social tensions. As we all know, the gas and oil reserves in Russia are not only in an economically but also politically far from stable region. Renewable resources in the Southwest of the US outgun the EU by an order of magnitude, yet go completely wasted.

If I had to make a more comparative statement, the US and the EU are like two families building a house. The US builds this huge mansion with many rooms and enormous pomp but without an architect. Many of the edges are rough and unrefined, other rooms are full with treasures but few of them are being used properly or diplayed in a tasteful fashion. In the EU there are many architects at work who are trying to build a much more refined, elegant and functional place. A place where everybody can feel at home and be proud of the premises. The lot the EU is buidling on is much smaller and it needs to take care of more inhabitants. It also has a much smaller loan from the bank than the US. Now, both are looking across the fence to the other side and both are jealous. The EU has a lot to be jealous about, the size of the lot, that quarry the stones come from etc.. The US is keenly aware that its neighbour has the better architects and contractors. The response to that is, IMHO, not always graceous. That is true for either side.

I would like the US to build a really solid house for itself. One that is a little bit more refined, like the one in Europe. Maybe PO will help us to get to such a mindset... who knows?

Even skipping the 20 million or so Mexicans (10 million legal, 10 million illegal) the whole key to the US economy is that the labour force can move around in search of better opportunities.

Read 'The Grapes of Wrath' by John Steinbeck if you think that hasn't caused social tensions in the past. Or any right wing shock jock on the Mexican immigration question now.

Europe is nowhere near this ideal, which is one of the reasons why convergence will take so long.

Right wingers always play the immigration and hate card. Go to Europe if you want to see how it is really done. Compared to that the US is harmless.

I agree that the EU is nowhere nearly as well integrated as the US. It probably never will be. It also does not have to be. The EU is not meant to be a clone of the US. The sooner Americans understand that, the sooner they can develop working diplomatic relations with the EU, again. Same for Asia... China is not a capimmunist clone of the US. Never will be... they have a 3000+ year administrative history over there. They culturally just laugh about a lot of things going on in the US.

Europe has 'gas' but has to compete with expanding economies and populations in Russia, North Africa and China for that gas.

Europe has little or no oil.

Europe is clearly a much more energy efficient society than the US, but therefore the US can make big savings relatively easily, whereas for Europe it is a long, slow grind.

The US has access to Canadian oil sands. There is gas in the Arctic and the US has more than abundant coal (which is a global warming problem of very serious dimension).

We have good public transport, but our goods and freight move by road whereas US long distance transport is often by rail. We are very dependent on short and medium haul airlines for communication.

Our economies are full of protected and subsidised niches, one reason why unemployment is so high (if it's hard to fire anyone, it is hard to hire them). And we have serious demographic problems: pensions are becoming an insuperable burden.

We have far more barriers to the movement of people to the jobs. If part of the USA is booming, people will move there to work. In Europe, we actually legally restrict that right of movement (ask any Bulgarian or Romanian!).

When exports dry up, currency strength and logisital advantages aren't going to mean much. Thus in the medium term I think Europe is in a weaker position.

Internally, Europe in is in a far worse position than North America when it comes to fossil energy reserves. See this comment here. I know that chart included with it has been presented here before. North America also has far greater potential for wind and solar production.

There are clear qualitative differences, but despite America's poor suburban infrastructure I think I'd rather be here than in Europe when things get bad. We can cut consumption dramatically and live poorly off our remaining fossil supplies. Europe, on the other hand, will have to live hand to mouth off of Russia and Central Asia's fossil energy reserves. The natural gas situation in north America can be handled by wearing heavier clothes and using electric heaters, dryers and stoves - essentially moving the NG burden to coal and a bit of nuclear.

Non-market action to obtain the barrel will make it disappear the next day.

I believe that my co-citizen, John McFadden, is arguing convincingly that Europe is positioned to use the marginal barrel more productively than the US. I concur and also believe that China is better positioned than both.

The US should be in a better comparative position to conserve, but effective conservation (which I define here as that which is most beneficial from an economic perspective) requires public investment. A lot of public investment.

Unfortunately for the US, and for those of us in Canada with the US anchor rope wound around our feet, public investment in effective conservation is playing second fiddle while Iraq burns. Even more unfortunately the US cannot now let go of Iraq because the game has become 'double or nothing'. Leave and the civil war could spill into the oilfields exacerbating the trend revealed by the export land model. Should have never kicked the tar baby.

Oh well, as the US elite fulfills its blood lust in Mesopotamia, the people of meso america are able to enjoy a period of respite.

This will only be true if oil remains a fungible commodity, a questionable proposition once the world is conscious of the implications of peak oil. I have no doubt that those who control and sell the oil will follow the principle you have outlined, but when, for example, poor people in Russia have their natural gas turned off because the people of Europe are willing to pay more money for the gas they are not going to sit idly by while they freeze to death. They will revolt, destroy energy infrastructure, and/or engage in political revolution to install leaders who will keep their fossil fuel production domestic. Once that activity is underway around the world, oil will cease to be a commodity with control of distribution largely shifting to governments. Because of this likely friction we're in for a long age of extremely repressive governments throughout most of the world, I think. I also think the chaos will prevent the world economy from functioning in the fluid manner we have been accustomed to since post WW2 anyway irregardless of the energy situation.

Yes, poor Canada, why won't someone play a small violin for our horrible plight. Canada suffers from the same suburban sprawl and mass transit underinvestment as America and Canadians use as much gasoline per capita as Americans. Also, to hell with the Kyoto protocols, there is money to be made in them there tar sands. If it will make you feel better you can brag about gay marriage rights and the low murder rate.

It just happens to live next to a country full of nutters ;-).

I was particularly struck by InfinitePossibilities' analogy of the architects. I've traveled extensively in the world and the first thing I notice is North America's lack of a sense of history or permanence. Compared with Europe there is a real sense that nothing should last more than a few years, from roads to buildings to the products we use every day. It really leaves the impression that we live in a "cardboard society."

The US and Canada are not as homogenious as might appear from afar. Both Canada and the US were built on their transportation and communications systems, with Confederation, in particular, being entered into suspiciously and cautiously as the railroads extended east and west from Montreal.

Within Canada, during the time of confederation there was wide spread economic disparity and special tariffs, the Crows Nest Rate in particular, were put in place to protect relative advantages. There are still more barriers to east/west trade than there are north/south trade.

Today, new economic disparities are showing up with the west having the upper hand. Onario's historically powerful manufacturing base is weakening substantially, while the west's energy and access to the Pacific is providing renewed interest in going it alone. Politically, Quebec's on again, off again interest in separation resulted in the recent Clarity Act. Quebec can separate if a clear majority answer a clear question. But the Clarity Act, while put in place for Quebec, holds equally for all Provinces.

The tar sands construction boom is taking a toll on Canada's labour market. Mobility in Canada isn't what it might seem as trade certification is a Provincial jurisdiction. An electrician licensed in Ontario is unqualified in Alberta. The same holds true many professions.

The recent and relatively unknown TILMA agreement between British Columbia and Alberta breaks down inter-provincial barriers, amongst other things. Ontario is hoping to gain manufacturing contracts in Alberta at the same time that Alberta is entering into contracts with China for heavy machine manufacturing. Any concessions that Ontario or Quebec may gain will certainly require them to enter into TILMA, which will make it easier for Alberta to lure away skilled trades and professions.

Newfoundland and the Maritimes have never enjoyed the economic prosperity of Confederation and have been the recipients of transfer payments from other parts of Canada. Newfoundland only joined Confederation in 1947, so Canada as a whole really is a very young country.

The US has similar regional inequities and barriers to mobility. The historically coal rich Appalations are the poorest and ecologically devastated region in the US. West Virginia has a literacy rate on par with third world nations.

Both countries have citizens who are equally comfortable in NYC or Los Angeles and own homes in both places, along with a summer home in Tuscany. But the vast majority of citizens feel tied to the land and regional values. A young francophone nephew of mine was tempted by a tar sands salary of $125,000 for driving a truck, but his wife refused to leave her roots. Paris is closer to Moscow than Montreal is to Athabasca.

There is slowly growing public awareness of the relatively secretive Security and Prosperity Pact, or North American Union, and the NAFTA superhighway. Tied in with that, in ways that are not clear, is the Amero, a new North American currency first proposed by the Canadian somewhat right of center Fraser Institute. The average North American citizen is virtually unaware of the SPP/NAU and the Amero, and what it means. However, the window of opportunity for both the US and Canadian governments to unilaterally (eg without legislative review) impose the NAU closes in June, 2007.

In terms of north/south mobility, ever since the enactment of NAFTA, I (holding the "right" kind of university degree) can go work indefinitely in the US simply by paying a $35 fee at the border crossing. NAFTA resulted in a "brain drain" into the US from Canada. I don't see the NAU being an invitation for the jobless and unskilled to flood into the US. Given the size of the US economy, the NAU is likely to be somewhat asymetric.

So you can see, there is a great deal of political and economic uncertainty in North America and there are growing regional imbalances. Canada, the US, and Mexico are in some very real sense, too large, nations joined together and held together by their transportation and communication systems. They are pulled apart by distinct differences in economics and value systems. To the extent that the average Canadian may wish to separate themselves from other Canadians, or distance themselves from the US, the Security and Prosperity Pact will certainly include provisions allowing the US to protect us from ourselves.

So while there are an infinite number of possibilities and future scenarios, and I'm not advocating or proposing any particular scenario, it isn't inconceivable that the nations of Canada, the US, and Mexico could splinter, perhaps violently, in the face of scarcity. If it does, it will be our youthful lack of common purpose and permanence, and our complete lack of a meaningful sense of history and community, that will drive the process.

These are interesting times.

Not a great novel, and certainly not one of his best, but his vision of a fragmented North America is interesting.

(someone told me he was born in Alberta, but I haven't been able to substantiate that)

Also, in a lighter vein, Connie Willis' 'Light Raid' which is about a war between East and West North America (fought with orbital lasers).

That's the fun of it.

And of course all you have to do to disprove it is put forward "[someone] with any strong grounding in oil production (and 'large project') data has called an abrupt and steep drop."

Clipping one line from a Simmons power-point (as has been done) doesn't do it, in my view. I'd like to see an honest and full estimate, for "abrupt" or "steep" drop.

Not at all. When I write of a poorer energy mix, I am referring to the impending ongoing decline and impending descent in natural gas supply among other factors.

I believe that North America is poorly placed to compete for oil going forward and that our real oil purchasing power is declining in relation to other economies, and will decline even more rapidly as peak energy-available-to-the-non-energy-producing-economy plays out.

That was the bit to which I was originally responding.

Like this?

2. Now you can choose the size of the picture you want (small medium large etc).

3.

Scroll down a bit and you'll see

"To link to this photo on other websites you can either:"

4. Select and copy all the text from Box 2

5. in your post write

<img src="paste URL here">

6. paste the url from box two into the image tage (replace paste url here, but keep the quotes)

7. double check with the preview button

That should do it

OR

You can copy all the text from box 1 into your post. But you have to delete title="Photo Sharing" because TOD chokes on that.

For anyone who is interested this chart is from here: http://www.vtpi.org/railcrit.pdf which is in itself a very worthwhile read for people involved in the public transit debate, and particularly discussions relating to rail transit vs other modes. Lots of information and good argument.

This particular chart I believe provides partial support of my contention upthread that the US economy is not well situated to compete for the marginal barrel of oil. Of course, more support could be provided by a similar picture of the return on investment for new roads in China, and elsewhere. But I anticipate that the return on investment in roads in China today is close to that of the US around 1960. There are other uses for oil that require examination, but since oil is primarily a fuel for transportation, I think this chart provides an important hint.

Back in the 80s, developers turned all sorts of aging, post-war apartment blocks into condos. Eventually these buildings needed serious repairs, and I read that condo owners found that their condo fees were approaching their mortgages. I could see that happening again as even shoddier new construction gets carved up for tiny flats and condos (read slums).

EROEI is going down for Oil & Gas, but not for other sources of electrical generation.

:-)

In addition to that, exporting countries may begin to see oil in the ground as a more valuable asset than dollars or euros or anything else. At that point, their incentives will change completely--saving the stuff will be better than producing all-out, because it will appreciate faster than other assets.

Mark Folsom

He (Toll) gave an interview in the Wall Street Journal last week. Unfortunately, a paid subscription is required to follow the link, and I could not find a free source.

Mr. Toll Turns to Towers

Coming down the 400 there is that sign 'welcome to Toronto, population 2.1 million'. That number hasn't changed since the early 1970s: the smaller average household size offsets the number of new units built.

The Greater Toronto Area has expanded hugely of course-- now as many as 6 million people I think. But I would say the majority (but not the overwhelming majority) of the housing units built are single family dwellings. That may be changing as land prices keep rising and there are mushrooming centres outside of the Metro (eg Vaughan).

So yes there are condos in downtown Toronto, (the previous big buildup of multiple unit housing was rental apartments from about 1948-62, those units are now in need of regeneration), but GTA remains predominantly a place of detached single family dwellings.

And it sprawls. I would say 60 miles by 60 miles, at least.

What I remember as open fields from the 70s, all the way to Barrie, have been muchly built over.

The City, my man, ends at Lawrence Avenue (or rather just before Hog's Hollow)-- beyond that is North York, which is Mel Lastman, suburban dream land! Etobicoke, Scarberia, North York-- phaughh, suburbs ;-).

In places like Post Road, they actually have a minimum lot size to keep the riff-raff from building $1million homes, which would cheapen a neighbourhood of $5million homes. Let them live in Rosedale, I say.

I grew up in a quadrangle bounded by Bathurst, Bayview, Lawrence and the Lakeshore-- for the first 26 years of my life, I never spent more than 2 weeks at a time outside of it.

Seriously though, although I hated Harris for a lot of reasons, the abolition of the burough governments had a point, which was that Toronto is now about Metro-not-Metro, not about Scarborough arguing with York re transport funds.

The Yonge-Sheppard corridor is really depressing. They have built the condos, but somehow the area just has no sense of life.

Why it took place is the subject of some discussion (1) but the effect has been to lead to a recolonisation of New York by the middle classes. Which has then led to their being driven out by the astronomical housing prices (and the poor quality of the schools, for those of family-building age).

(1)

Theories abound, depending on your left/ right wingedness of views:

- legalisation of abortion leading to a fall in the number of 18 year olds from the 'most vulnerable' (to criminality) categories (Stephen Levitt 'Freakonomics')

- abolition of lead containing petrol leading to a decline in attention deficit disorder and a rise in IQ amongst children

- 'hard core' policing methods such as zero tolerance, increase in incarceration rates etc.

- turfing the homeless off the island of Manhattan eg by closing the welfare hotels

- fall in the number of 18 year olds (the biggest committers of street crime)

- the crack epidemic burning itself out

Whilst I think the Levitt thesis (and the leaded petrol one) may have a lot of explanatory power, particularly when looking at the US as a whole, in the case of New York I think we have to credit the big increase in numbers of police on the street (begun under Mayor Dinkins) and the rigorous emphasis on reducing crime statistics, block by block, using preventative policing (especially eg arresting transit fare evaders, who often turned out to have concealed weapons and/or to be on the way to commit other crimes-- a form of self selection), using the COMPSTAT database and new police management tools (Police Chief William Bratton, and Mayor Rudi Giuliani).To some extent Bratton invented it, and Giuliani took the credit, but actually making the police police (rather than sitting in cars or in the office filling out reports) (2) and then allowing them to make arrests, and putting the perpetrators behind bars (so there was a real cost to a potential perp), seems to me to have been a huge factor in cleaning up NYC.

(2) a GE axiom of management. That which you can measure, and you do measure, and hold people accountable for, they will address and seek to do.

How hardened is your town/cities economy against peak oil.

For example you can figure that cities along the Mississippi drainage will probably do okay since they would have barge traffic and of course its all fertile farmland. The same for cities with good ports. World trade is not going to come to a standstill overnight.

Otherwise I think we have a lot of cities in America at least that may not make economic sense in a post peak world.

For example Tulsa Ok sure still navigable. Wichita Kansas ?