Tech Talk - Current Oil Production and the Future of Ghawar

Posted by Heading Out on June 18, 2012 - 12:17pm

There is a growing impression being given in the discussion of oil and natural gas supplies that the world is moving into a period where there will soon be such a plentiful sufficiency of crude that the US may consider exporting some of its production (h/t Leanan). But if one looks behind the headlines, and particularly at the current status of the largest oilfield contributing toward this rosy picture - the Ghawar field in Saudi Arabia - that optimism becomes more evidently built on a very transient set of data that, as this series of posts seeks to show, will not be sustainable for any significant period into the future.

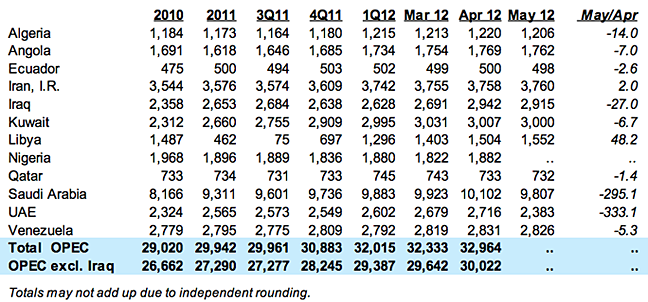

The three major oil producers (i.e. those producing more than 5 mbd each) are currently seeing surges in production as the world moves to an overall production of 90 mbd. The OPEC June Monthly Oil Market Report (MOMR) notes that this has brought Russia to 10.33 mbd in May, some 100 kbd over the same period in 2011; and Saudi Arabia is reported to have averaged 9.917 mbd in May, up 40 kbd over April. The United States is running at 6.236 Mbd of crude (from the EIA TWIP), while importing 9.117 mbd. The MOMR reports US oil supply at 9.66 mbd on average, but counts more than just crude in this value. The gain over the past year is around 600 kbd. It is interesting to note, in regard to OPEC production the continued difference between the volumes that OPEC reports from direct contact with the suppliers, and that when the numbers are obtained from “secondary sources.”

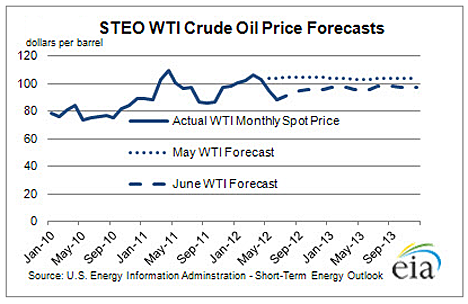

This surge from the majors has in part led the EIA to project that oil prices will remain relatively stable for the remainder of the year.

In the short term, and leading into a national election, there is no significant event (short of a hurricane or two) that obviously threatens this projection, though the Iranian situation and the questionable stability of nations in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) has to remain a concern. Sadly, the continued ill health of the global economy, with no evident savior or realistic plan for growth now visible, means that the demand OPEC projects - 1.17 mbd y-o-y on average this year - may continue to be met.

However, I have given my reasons in previous posts for anticipating that the surge in both Russian production and in the United States are at near peak, and will soon decline. Saudi Arabia's fall will be less dramatic and a little later, but the combination does not bode well for the international supply in the next presidential term.

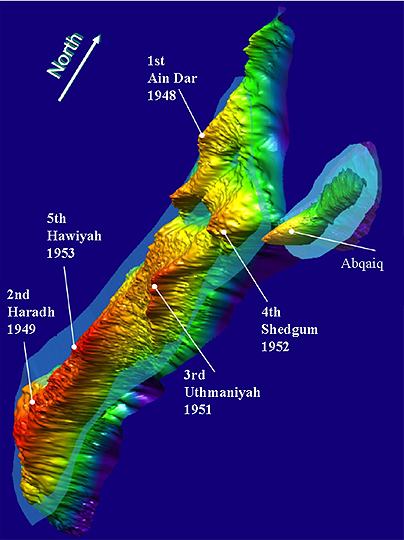

The big question with Saudi Arabian production to date has been more focused on the production from Ghawar, which at 5 mbd has been the rock on which the overall production builds. But that rock is continuously eroding under the long production periods that its different regions have seen.

The final major new effort to bring new production on line in the overall field was the effort at Haradh, down in the South tip of the field.

JoulesBurn has written comprehensively on this region, beginning with the first well that came into production. In 1979, as the late Matt Simmons pointed out in “Twilight in the Desert”, the three northern segments of Ghawar, Ain Dar, Shedgum and North Uthmaniyah were producing 4.2 mbd of the 5.3 mbd total Ghawar output, with South Uthmaniyah producing another 400 kbd. By 2006 North Uthmaniyah was running at a 46% water cut.

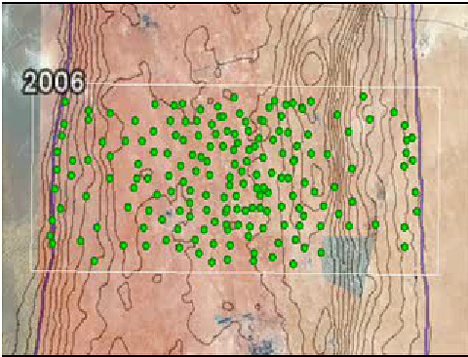

Joules has taken the historic record for that region of the field and made a short movie presentation included in a post that shows how Uthmaniyah was developed over the years.

The sequence of wells shows how the wells had to move inexorably to the crest of the field as the underlying reservoir became more depleted in oil. Uthmaniyah is the region where the test program to inject carbon dioxide to enhance EOR is under construction, as mentioned earlier, and scheduled for completion in the fourth quarter of 2013. It is worth noting that Aramco is also planning to use more steam injection for enhanced oil recovery (EOR), and that plans have just been signed to increase steam production at the Ju’aymah, Shedgum and Uthmaniyah plants, with completion dates in 2014 and 2015.

As one moves south, the quality of the reservoir changes, and becomes more difficult to produce. However, as Greg Croft has noted, the two lower segments of the field Hawiyah and Haradh were developed with horizontal wells rather than the vertical wells further north in Ghawar. This has overcome some of the geological constraints and the fact that the productivity index drops from around 140 barrels of oil per day/psi to 45 BOPD/psi at Hawiyah, and 31 at Haradh. In 2008, the Hawiyah NGL recovery plant was commissioned, to yield 310 kbd of ethane and NGL.

The further development of the lowest segment of Ghawar, down at Haradh, was one of the major projects that Aramco listed as contributing to their ability to produce up to 12.5 mbd. The latest development built on earlier development, and because the use of horizontal wells had transitioned into maximum reservoir contact (MRC) designs by the time of Haradh III reduced the anticipated number of wells from 280 verticals to 32 MRC wells.

In his initial review of how that developed, JoulesBurn showed how the wells were developed and laid out and explained how he was able to use satellite images to determine the different components of the production equipment.

It is relevant to note that Joules updated his view of the region in 2010 when he noted that after looking at the satellite images of the region, he was able to show that instead of the production coming from the original 32 wells, there were actually some 52 production wells connected up, which – as he noted – raises a few questions as to the actual performance of the wells over the original projections.

However, Aramco reported(pdf) using Real-Time Reserve Management, that it had been more successful than anticipated by the summer of 2009.

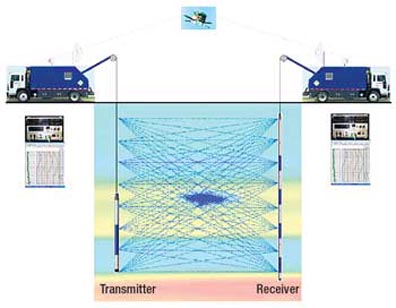

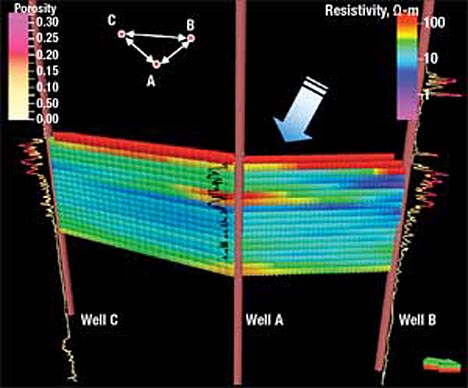

Some of the additional wells drilled were to allow cross-hole tomography (pdf) to monitor the location of the oil:water front, which as production evolved, did not follow the anticipated path. This was particularly important to establish given the 1 km spacing between wells and the more complex geology relative to that further north in Ghawar.

What is also clear, however, from looking at the different regions of Ghawar, is that there are no places left for new programs to restore production as wells become exhausted. If KSA is to sustain its production it must look beyond the King of Oil Fields, which now lies stricken in years.

A couple of notes on Haradh:

The RTRM paper essentially refers to the wells drilled as part of the original Haradh-III project. I still can't fathom why, if things performed beyond expectations, they would drill still more wells -unless they decided to extract at a higher rate.

The Crosswell EM paper is talking about a different part of Haradh (the Haradh-I increment). The first clue is this bit:

which describes the situation in the north part of Haradh, which was originally developed with vertical wells. The figure to the right shows the location of the project (red dot). It was the behavior of the rock in Haradh-I which motivated the evolution to horizontal wells (Haradh-II) and then MRC wells in Haradh-III.

A more recent paper is:

First Borehole to Surface Electromagnetic Survey in KSA: Reservoir Mapping and

Monitoring at a New Scale

which discusses a similar experiment at the same location in Haradh (although they don't say so). These were both demonstration projects, however, and I haven't seen any reports that either has to date been used to help guide the placement of additional wells in Ghawar. From Fig. 15 in the above pdf, it is clear they chose this location because it is right at the water front such that the EM approaches could be tested on both oil-laden and flooded out rock.

On a related note, as I related here here, Saudi Aramco increased the amount of water flowing to Haradh for injection. Why?

Heading Out, Joules or anyone else, what do you make of the tremendous difference in production in what OPEC reports from their "secondary sources" and what they report from "direct communication" with OPEC members?

I have long been familiar with the almost half a million barrels per day that Venezuela always reports verses what the OMR "secondary sources" reports. Venezuela reports far more than they actually produce in an attempt to show that they are producing as much as they were before the strike, or at least that is the explanation I have read elsewhere.

But what concerns me is the drop in production of 295 kb/d from Saudi Arabia and the drop of 333 kb/d reported by the UAE, which was not reported by their secondary sources. What reason would Saudi and the UAE have for reporting such a large drop if it did not actually happen? Or did it happen?

I reported this strange discrepancy on Drumbeat on June, 13 but no one ventured any guess as to why it happened.

Ron P.

Hi Ron

Not to sound like a conspiracy wank, but do you think the difference between actual and initial reports is by request from Governments with a strong worry or interest in finacial swings? Or, perhaps a lot of Saudi wealth is also stomping around the markets and it behooves them to keep the myth going?

Paulo

Well it is not really "actual and initial reports" but what Saudi and the UAE say they produced versus what others, outside Saudi and the UAE say they produced. We have no way of knowing which was the initial report or which one is actually closes to their actual production.

No I don't think it is any kind of conspiracy, but perhaps Saudi and the UAE wish to claim that they are actually cutting production when they are actually doing no such thing. They want to keep prices from plunging any further and also placate other OPEC members who want them to cut back. In other words they are just lying about it but not colluding with anyone in any kind of conspiracy.

Ron P.

Hi Ron,

I think the explanation you give here is best. When Opec members are producing at levels higher than their quota they lie about their output levels (they say they are producing less than actual production) and the secondary sources should be trusted. When Opec runs low on spare capacity and importers are complaining that Opec is not producing enough (early summer 2008 and during the Libyan civil war)then the numbers reported by Opec members may be accurate. This same argument might apply to Jodi data as well, but there is also an issue with oil sands production and how that is reported to jodi by canada which complicates matters, the Russian jodi data also does not agree well with EIA data.

DC

Storage being run down and then replenished? One or other of them counting some April production against May or vice versa? Someone thought May 1st was April 31st? Venezuela clearly lies but I don't see Saudi as outside the noise from counting the same thing at different times in different places.

Truth is the First Causality of War

Both KSA and UAE are in an economic war with Iran - with oil as a weapon.

The reasons to overstate, or understate, oil production by KSA, UAE and Iran will vary, but "truth in reporting" is simply not a priority.

Alan

Re: tremendous difference in production

How does Platts (or any other secondary source) know what Saudi Aramco is producing (i.e. extracting from the ground)? Aramco has their own tankers as well as storage facilities (and refineries) around the globe. Is Platts just counting barrels released to the market (assuming they can ascertain that), whereas KSA is referring to extraction? Then there is the shared Neutral Zone production, the 150 kbarrels/day that KSA produces but Bahrain sells, and the fact that condensate is not counted by OPEC.

Is a 3% discrepancy under these circumstances really tremendous?

When 3% comes to 295,000 barrels per day, yes it is quite significant if not tremendous. And in the case of the UAE, who reported a drop of 333,000 barrels per day which is more than 12% of their daily production. Now that is tremendous. And combining the two, "direct communication" reported a drop of well over 600,000 barrels per day, which should make headlines in any newspaper. It did not of course because no one really believed them.

If the estimators, or guesstimators, on either side are off by 12 percent then there is little point in estimating production levels at all.

Ron P.

The 500 kb/d discrepancy between EIA and RRC for Texas production noted by westtexas is ca. 20%. I bring this up merely to note that these things can happen even in the most drilled nation on earth. This discrepancy has always been there, too, it's just that of late it's become much more pronounced for some reason, after increasing each year since 1981.

The EIA/IEA/JODI numbers have never lined up either, albeit they've usually been close. What OPEC are up to is a mystery. Perhaps they want to illuminate the very fact of these discrepancies, to bring about better methodology in accounting for barrels. I can see the KSA seeing this as a new tactic to bring other OPEC members in line.

IEA numbers are courtesy Oil Movements, right? Charles Mackay would know. EIA use IHS, if I recall correctly.

KLR - I'm not 100% sure but it looks like the EIA uses the production number the CA oil regulators collect. So those should be very accurate. I'm not sure if they use the data collected by other state agencies though. And it still leaves the question: if they trust the CA regulator numbers why not the TRRC? Another question: I'm certain the EIA is aware of the varience between their estimates and the TRRC numbers so why no explanation? If they have a good reason to reject those numbers why not explain it?

Hi Rockman,

So, here is some of that "growing impression":

Patti Domm a CNBC Executive News Editor said today (6/22/12):

Given that PO folks have often stated that oil production peaked around 2006 @ 85 mbd (or numbers close to that) how can we expect the general public to understand the underlying issues as discussed in this post? Certainly, nearly all TOD readers understand that the 85 and 91 figures are not measuring the same thing (actual oil vs all liquids); but why is it that the "expert", Patti Domm, does not seem to think this is significant enough to point out?

It's a bit frustrating to always see these fine points discussed in a place like TOD, while the general public is being fed the "feel good" stuff from places like CNBC.

There are two points I think it is necessary to make:

1. OPEC production continues to increase, albeit marginally. This is contrary to the predictions of the doomers in the Peak Oil community. After seeing prophesies of doom not materialise, I think people should be somewhat sceptical of tomorrow's prophesies of doom. The theory of Peak Oil is unassailable, unless you happen to be one of those "New Earth" people who believe the world is only 6,000 odd years old and more oil is being created all the time. The latter, of course, are beyond logical argument and should be treated gently until they come to their senses, unless they try to interrupt the conversations of the reality-based community.

The theory of Peak Oil is one thing, but predictions of a peak this year or next are another thing, while predictions of catastrophic consequences of a decline in production are yet another. The failure of OPEC production to collapse, and the recent increase in US production, should serve as cautionary tales for the Chicken Littles of this world. Peak Oil people who are pessimists should check the assumptions that have caused previous predictions of doom to fail to eventuate and re-think them rather than merely re-base them. Perhaps the crunch is not immediate and/or perhaps the pain will be transformative rather than crippling. People are ingenious and, given a pressing problem, can dump previous patterns of thought and action that have proven to be harmful. The doomers, I fear, assume that people can't adapt and the only alternative to the status quo is collapse.

2. The sooner Ghawar waters out, the better it is for the world. This event will have two enormous benefits:

(a) It will be a wake-up call for the entire world and destroy the credibility of the cornucopians. Peak Oil will have to be accepted as a geological reality and the world will be able to begin discussion of the transition to an oil-free economy in a new way.

(b) It will be the end of the road for the House of Saud. What I think of this bunch of tyrants is unprintable, but when Ghawar waters out, the gig will be up for them. The people of Arabia will be forced to begin to modernise their society, rather than have oil money spent like water to reinforce social structures from a millenium ago. At first, there may well be some uncomfortable and unpleasant symptoms, but the removal of a discredited absolute monarchy will produce social changes that, in a few decades, will have major beneficial results. Further, because the malign influence of the House of Saud spreads far beyond the borders of Arabia, its fall will remove a vicious source of reaction that is warping social processes in many countries*.

* Just to cite one example, the House of Saud is arming the opposition forces in Syria and, in the process, transforming them. What started out as a non-sectarian movement, committed to the least possible use of violence in order not to militarise the struggle, has changed completely because of who the House of Saud has decided to arm. It is now much more of a sectarian struggle between a Sunni Muslim opposition, armed by the House of Saud, and an Alawite government, which the House of Saud sees as heretics.