Has the Global Economy Become Less Vulnerable to Oil Price Shocks?

Posted by JoulesBurn on March 14, 2012 - 1:15pm

This is a guest post by Dr. Mingqi Li, an associate professor of economics at the University of Utah.

Abstract

This paper examines the impact of oil price changes on global economic growth. Unlike some recent studies, this paper finds that oil price rises have had significant negative impacts on world economic growth. A time-series analysis of the data from 1971 to 2010 finds that an increase in real oil price by 10 dollars is associated with a reduction of world economic growth rate by between 0.4 and 1% in the following year. As oil prices approach historical highs, the global economy may be vulnerable to another oil price shock.

As oil prices approach historical record levels, the debate on how important the impact of oil price changes is on the global economy has been resumed. Most recently, a paper by Tobias Rasmussen and Agustin Roitman, two IMF economists, finds that oil price rises have generally been associated with good times in the global economy. The authors do concede that for OECD economies, oil price shocks have lagged negative effects on the output, but insist that the effects have been small: for oil importing countries, a 25% increase in oil price is found to be associated with only 0.3% decline in output over two years (“Oil Shocks around the World: Are They Really That Bad?”, posted at the Oil Drum, http://www.theoildrum.com/node/8944).

Rasmussen and Roitman describe the observed association of high oil prices and contemporaneous rapid economic growth as “surprising.” In fact, there should be nothing “surprising” about this finding. As the economy grows rapidly, demand for oil is likely to be high, driving up oil prices. Thus, as far as the impact of oil prices on economic growth is concerned (rather than the impact of economic growth on oil prices), only an examination of the lagged effects of oil price changes would be meaningful.

Rasmussen and Roitman conducted the study using a cross-national approach, which gave some of the tiny economies the same weight as continent-sized economies such as the United States. Unlike Rasmussen and Roitman, this paper evaluates the impact of oil prices on economic growth for the global economy as a whole.

The next section provides some basic observations considering the relationships between world economic growth, oil prices, and oil consumption. This is followed by a more formal time-series regression analysis which finds that oil price rises have significant negative impacts on world economic growth.

The Big Picture: Some Observations

It is well known that world economic growth depends on the constant expansion of energy supply, and oil accounts for about 40% of the world energy consumption and almost all of the transportation fuels. Thus, the global economy depends on oil for normal functioning in the purely physical sense.

However, it is commonly argued that over the years, the oil intensity of the global economy has dramatically declined and as a result, the global economy has become less vulnerable to oil shocks.

It is true that measured by oil consumption per dollar of world GDP, world average oil intensity has declined from 0.116 kilogram per dollar in 1980 to 0.060 kilogram per dollar in 2010 (measured in 2005 purchasing power parity dollars), or oil intensity has fallen by about half over three decades.

However, this observation by itself does not tell us if the world economic growth has become less dependent on oil consumption growth. Consider two cars: suppose car A is twice as energy efficient as car B. With access to fuel, car A can drive twice as long as car B with the same amount of fuel. But if additional fuel supply is zero, then neither of the two cars can operate any more.

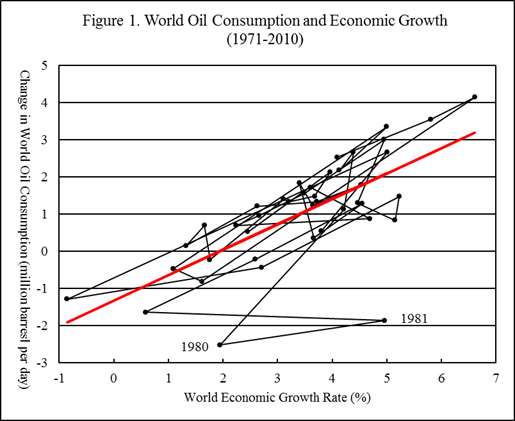

Figure 1 shows the historical relationship between world economic growth rates and the annual changes in oil consumption from 1971 to 2011.

A simple bivariate regression produces the following result:

Change in Oil Consumption = -1.32 + 0.68 * Economic Growth Rate

The above result says that the world economy can grow at approximately 2% a year without requiring any increase in oil consumption. This might be called the “breakeven” world economic growth rate for oil consumption purpose. However, beyond 2%, an increase in world economic growth rate by one percentage point needs to be associated with an increase in oil consumption by near 700,000 barrels a day.

For example, if the world economy grows at 3.5% a year, the above equation implies that the world daily oil consumption needs to increase by 1.06 million barrels a year.

With the exception of 1980 and 1981, all other observations stay very close to the trend line, suggesting that the observed relationship is robust. Regression R-square is 0.510, or rather, world economic growth alone can explain 51% of the observed variations in oil consumption.

A regression that only uses the data from 2001 to 2011 finds that:

Change in Oil Consumption = -0.85 + 0.53 * Economic Growth Rate

The slope on the economic growth rate is now somewhat smaller. But note that the “breakeven” economic growth rate now falls to about 1.6%. Evaluated at 3.5% economic growth rate, the associated annual increase in oil consumption is 1.01 million barrels a day. Thus, as far as the relationship between world economic growth and oil consumption growth is concerned, there is little evidence suggesting that world economic growth has become less dependent on oil in recent years.

The above simple analysis suggests that any economic growth rate above 2% a year (an economic growth rate that would be required to lower unemployment rates in most countries in the world) would require positive growth in oil consumption.

However, a growing body of literature now suggests that world oil production may peak in the near future. It remains unclear when exactly world oil production peak will happen. What has become clear is that world oil supply has become much less responsive to world oil price increases.

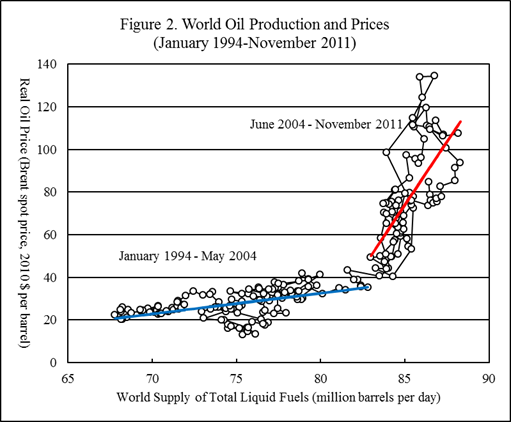

Figure 2 shows the historical relationship between world oil supply and real oil prices (oil prices in constant 2010 dollars, that is, oil prices corrected for inflation).

From January 1994 to May 2004, on average, it took only an increase in oil price by 0.97 dollar to bring about one million barrels of additional daily oil supply. From June 2004 to November 2011, in average, it took an increase in oil price by 11.8 dollars to bring about an increase in daily oil supply by one million barrels. Thus, the observed “world oil supply curve” had become dramatically steepened by almost 12 times. The dramatic steepening of the world oil supply curve has important implications for the prospect of world economic growth.

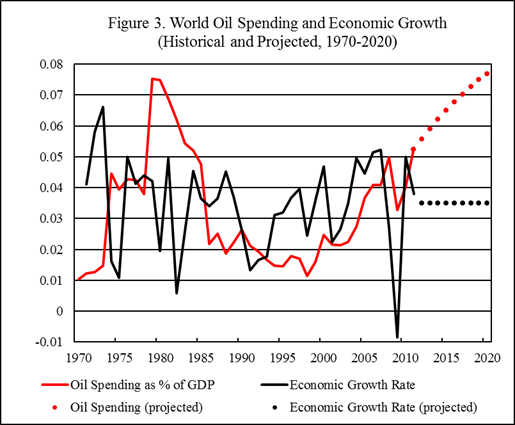

Figure 3 compares the historical world economic growth rates with the share of world oil spending in world GDP.

Historically, 4% of world GDP appeared to be a dangerous threshold. Whenever the world oil spending rose above 4% of world GDP for a sustained period of time, global economy had suffered from major instabilities.

From 1974 to 1985, the world oil spending stayed above 4% of world GDP for about a decade. During the decade, the global economy suffered three deep recessions: 1974-75, 1980, and 1982 (when world economic growth rate falls below 2%, it is commonly considered to be a deep global economic recession).

World oil spending entered into this dangerous territory again in 2006 and 2007 and hit 5% of world GDP in 2008. In 2009, global economy contracted in absolute term for the first time after the Second World War. Based on preliminary estimate, world oil spending again rose above 5% of world GDP in 2011.

If one assumes that the world economy will grow at 3.5% a year from 2012 to 2020 and world daily oil consumption will grow by one million barrels a year. Given the observed world oil supply curve, suppose the oil price rises by 10 dollars a year. Then, by the end of the decade, world oil price will rise to 200 dollars a barrel and world oil spending will rise to 7.7% of world GDP.

Given the historical evidence, it is almost certain that the global economy will not be able to survive such a dramatic increase in oil spending burden without suffering from some major recessions.

Thus, unless the world oil supply curve becomes flattened in the coming years, the world oil supply does not seem to be able to sustain a global economy expanding at a rate of 3.5% a year or above.

Oil Price and Economic Growth: A Time-Series Analysis

In this section, I conduct a simple time-series analysis to evaluate the impact of oil price changes on world economic growth. All data are from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators, except the real oil prices (in constant 2010 dollars) which are from the BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

To have a more accurate examination of the impact of oil price on economic growth, it is necessary to take into account other factors that are likely to have impact on economic growth, so that one does not mistakenly interpret the contributions from other factors as impacts resulting from oil price changes.

In the economic theory, it is usually believed that economic growth results from contributions of labor force, human capital, physical capital, and “total factor productivity” (a residual term that may reflect technological progress and institutional change).

In this study, in addition to real oil price, the explanatory variables include gross capital formation as percent of GDP (as a proxy of physical capital contribution); annual growth rate of labor force, life expectancy at birth (as a proxy of health conditions of the population); age dependency ratio (old and young dependent population as percent of working-age population, as a measure of the burden on working-age population); education expenditures as percent of gross national income (as a proxy for human capital contribution), trade in goods and services as percent of GDP (as a measure of “globalization” which may have impact on economic institutions and the pace of technological progress); broad money supply as percent of GDP (as a measure of financial integration and possible impacts of macroeconomic policies); and alternative energy as percent of total energy use (as a measure of substitution of renewable and nuclear energies for fossil fuels).

The dependent variable (that is, the variable to be explained) is the annual growth rate of world real GDP.

To control for the problem of auto-correlation (a common technical problem in time series analysis), all variables have been first differenced, that is, using the variables in the current period less the variables in the previous period. The real oil prices are also first differenced and lagged by one year.

Table 1 summarizes the results of alternative regression analyses.

|

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

|

Data |

1972-2010 |

1972-2010 |

1972-2010 |

1972-2010 |

1991-2010 |

2001-2010 |

|

Exp. Var.: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intercept |

0.058 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Gr. Cap. For. |

1.177* |

1.174* |

0.928** |

0.851** |

1.03*** |

0.926* |

|

Labor Force |

-0.232 |

-0.300 |

|

|

|

|

|

Life Exp. |

-4.240 |

-4.199 |

|

|

|

|

|

Age Dep. |

-0.389 |

-0.468 |

-0.344 |

|

|

|

|

Education |

1.316 |

1.324 |

1.170 |

|

|

|

|

Trade |

-0.090 |

-0.086 |

|

|

|

|

|

Br. Money |

-0.009 |

-0.007 |

|

|

|

|

|

Alt. Energy |

0.189 |

0.201 |

|

|

|

|

|

Oil Price |

-0.037 |

-0.037 |

-0.042* |

-0.041* |

-0.090*** |

-0.096** |

|

R-square |

0.324 |

0.324 |

0.315 |

0.295 |

0.744 |

0.793 |

(Dependent Variable: annual growth rate of real GDP)

* Statistically significant at 90% level.

** Statistically significant at 95% level.

*** Statistically significant at 99% level.

In the first regression, all possible explanatory variables are included. However, only gross capital formation is “statistically significant” (that is, the standard error is sufficiently small so that the estimated coefficient has a more than 90% statistical chance to be different zero). The estimate coefficient for real oil price has the right sign. It says that an increase of real oil price by one dollar would lower the world economic growth rate by 0.037% in the following year. However, the estimated coefficient for real oil price is not statistically significant (there is “only” 82% chance for the estimated coefficient to be statistically different from zero).

Note that the intercept is very small. In fact, the standard error for the intercept is so large that there is 96% chance for the intercept to be not different zero. Thus, in the remaining regressions, zero intercept is imposed. As the dependent variable (real GDP growth rate) has been first differenced, this effectively assumes that there is no long-term trend for real GDP growth rate to either accelerate or decelerate other than because of changes in the explanatory variables.

In the second regression, most explanatory variables remain statistically insignificant. For example, there is 96%, 92%, 87%, 71%, and 64% chance for broad money supply, labor force, alternative energy, trade, and life expectancy respectively to be statistically not different from zero. This suggests that these variables most likely have little impact on economic growth and the inclusion of these variables in regression would only generate “noise” that would make the estimated coefficients for other variables less accurate.

In the third regression, the statistically least significant variables are excluded. The estimated coefficient for real oil price now rises to 0.042 and becomes statistically significant.

The fourth regression only includes the two statistically significant explanatory variables: gross capital formation and real oil price. The first four regressions use all data from 1971 to 2010 (the data set after first differencing is from 1972 to 2010). The fifth regression uses data from 1991 to 2010 and the sixth uses data from 2001 to 2010.

According to the fifth and sixth regression, an increase in real oil price by one dollar would cause world economic growth rate to fall by 0.09 and 0.096% in the following year and the estimated coefficients are statistically highly significant. These results contradict the belief that in recent years the global economy has become less vulnerable to oil price shocks in comparison to earlier decades.

Conclusion

This paper examines the impact of oil price changes on global economic growth. Unlike some of the recent studies, this paper finds that oil price rises have had significant negative impact on world economic growth rates.

A time-series analysis of the data from 1971 to 2010 finds that an increase in real oil price by one dollar is associated with a reduction of world economic growth rate by between 0.04 and 0.1% in the following year. Therefore, an increase in real oil price by 10 dollars would be associated with a reduction of world economic growth rate by between 0.4 and 1% in the following year. For a global economy that in average grows at about 3.5% a year, a reduction of this size is very significant.

Moreover, the regressions seem to have suggested that the impact of oil price on economic growth may have increased over the last one or two decades. This is in contradiction with the widely held belief that the global economy has become less vulnerable to oil price shocks.

These findings suggest that if the world oil production does peak and start to decline in the near future, it may impose a serious and possibly an insurmountable speed limit on the pace of global economic expansion.

We could be six months away from higher prices than in 2008. The depression has lasted longer than expected, but soon it will turn into mad max. We are now at global peak coal, and soon nat. gas. Nuclear has a cultural taboo on it, especially after Fukushima. We are going back to the 1800s.

Nuclear has much more than a "cultural taboo", it has high costs and a record of rare but extremely damaging failures, despite limited use for only 60ish years. It also does little for transport, which is the main use of oil. There are good reasons to believe that nuclear fission energy costs more than it is worth.

I don't think we're going to go back to the 1800's at all. The population is too high, and there have been too many other changes since then. We may end up even worse off, or we may end up with a better than expected end result. I am personally a doomer in that I expect it to fall on the bad end of the spectrum, but when and how bad, and what good things may offset the bad, I don't know.

If you have the free time, you might want to pick up a copy of the new book "plentiful energy," by Dr. Charles Till, or my book, "The nuclear economy." The infinite growth paradigm that has been killing us all is now coming to an end, thank nature. By the time the IFRs take over around 2050, we will be like the amish. Nuclear has a promising future because there is no alternative, but it won't be abused for exponential growth the way fossil fuels were. I am a doomer too, but I am confident that we will come out better in the end.

Well, I'm glad to see the data suggesting that the world can grow at 2% pa with no growth in oil consumption. That should put a cat amongst a few pigeons. Shouldn't be a surprise though.

Not sure about the data regression to $1=0.04% growth rate reduction. Curve fitting without a working model behind it tends to bring forth the warning "correlation does not imply causation". Not only that, but there are delayed impacts of oil price rises at varying time horizons, not just one, as the many feedback loops in society play out and interact. I'd be happier with a model that explicitly includes that fact, and just uses data to correlate the model to reality. Seems like the approach taken in its economic viewpoint suffers from the usual problem of economic viewpoints (they are wrong, sorry, a poor fit with reality).

Oh, and as far as Fig 2 is concerned, matching lines rather than curves? It's crying out of an asymptotic curve fit.

I could believe that in a limited fashion increases in efficiency and economic fungibility could maintain "growth" of some nature. But I would expect some creaming off of this effect in time as barriers are hit. Harder to pin down and may in part represent increasing costs expressed as GDP which gives the illusion of increasing prosperity.

But that's money all over... a bit of an illusion.

Yea. I wonder what happens when you factor out all the illusory wealth (from GDP) that has resulted from the growth of the financial sector. The use of oil relates to actual physical work done to create real wealth, or at least transport it to markets. The financial sector has created a phoney bubble of money-based wealth that goes into the GDP computations but is only very poorly related to oil consumption. I suspect the relation between oil and the real economy is much more brutal than this paper suggests (although I think this is a good start at the right kind of analysis). Indeed it occurs to me that the only thing now propping up the GDP numbers is the frantic attempts by the financial sector, aided an abetted by the Fed and government, to keep the illusion going. If only that damned housing market and new construction would cooperate!

Money, stocks and bonds and other financial assets are not part of GDP. Financial capital is a stock concept and not a flow. GDP is strictly a flow concept. Of course, a huge change in financial assets will have some effect on both real and nominal GDP growth, but these changes in the value of assets are never counted as part of GDP.

Are you sure, Don? I thought that borrowing was included as a positive contribution to GDP, just like reporting a new mortgage as income, but I could be wrong.

Yes, I'm sure.

There is some connection between increasing business borrowing (which increases debt) and the accumulation of capital goods, such as buildings, machines, tools, trucks and drilling rigs, and inventories and the investment part of GDP. Note that in economics "investment" is a flow concept and has nothing to do with "investments," in ordinary conversation.

Consumption can also be financed by increasing consumer dept. Note again that consumption is a flow concept and has nothing directly to do with debt, which is a stock.

Economics has a lot of flaws, but it has a remarkably clear and unambiguous vocabulary. The reason most people don't understand economics is that they do not know the meanings of terms in economics.

If you borrow $100,000 for a new mortgage, the only thing that affects the GDP is the interest you pay, which shows up as somebody's income. If you got the loan to build a house, the GDP does count what you pay the contractor, what he pays his sub-contractor, the cost of materials, etc. If, however, you use the $100,000 to buy a piece of unimproved land, there is no contribution to GDP from this transaction because all you are doing is changing one kind of asset for another--land for money.

Interesting, lets see if i can muddy the waters.

If I take a mortgage of 100.000 to buy a house, the interest of 4.000 affects GDP, right? And if i buy the same house for 200.000, the interest becomes 8.000, and so GDP is bigger as a result.

If I buy a truck for 50.000, is that an asset changing hands? So no increase in GDP? If so, is there anything i can buy that will increase GDP? If not, does buying and then selling again something for the same price increase GDP?

But my favorite problem with GDP is a pair of mothers with a single child. Under normal circumstances, they'd take care of their own children, but my country is trying to stimulate everyone to work - including mothers. So now these two mothers pay eachother to look after the others' child. In reality, nothing changed, but in economics, both are now performing a service for the other, so the GDP is increased.

Not trying to be dense, just interested how an economist looks at these issues.

There are many problems with the GDP concept. One of them is that it excludes the underground economy. Another is that whatever does not go through the market (For example, produce from your home garden.) does not get counted. You are right in your pair of mothers example.

You may be surprised how truck sales are counted: If a business buys a Ford 150 truck it is counted as investment, and the tax benefits you get are restricted to how fast the IRS will allow you to depreciate the truck. Now, if a consumer buys the identical truck (for non-business purposes) it gets counted in GDP as part of consumption.

The pair of mothers would never do that - it would be pretty clear they'd lose money. One of them would take care of both the kids, while the 2nd mother would do something else that paid much more than she would pay the 1st mother for childcare. The 2nd mother might work for $25k per year, while she paid the 1st mother $7k per year.

The consumer truck purchase is not counted as part of GDP - like the land, it's two assets being exchanged. Surprisingly, the truck is counted as part of GDP when it's manufactured and added to inventory. That means that economists are always scrutinizing inventory changes, to see how much they added to or subtracted from the latest GDP figures.

OK, let's take a different example. We have two parallel worlds.

In World A, Bill and Joe are friends. Bill asks Joe to come around for dinner and cooks him a nice meal. While he's there, Joe notices that Bill needs a haircut and so gives him one. No money changes hands.

In World B, Bill runs a restaurant and Joe is a barber. Bill goes to Joe's barber shop and gets a haircut. He pays with a $20 note. That evening, Joe goes to Bill's restaurant and buys a nice meal. He pays with the same $20 note that Joe gave him earlier that day.

Compared to World A, World B is richer by $40 GDP and poorer by one friendship.

You are correct in your example. This idea shows how difficult it is to compare the GDP per capita of poor and rich countries. In poor countries, relatively few goods and far fewer services go through the market; instead a great deal of production is done at home (e.g. subsistence farming).

By way of contrast, in countries with a high GDP per capita, more and more production and distribution of goods and services goes through the market.

The best book I know of that discusses these topics is "The Great Transformation" by Karl Polanyi(sp?). He emphasizes the social changes that took place during the Industrial revolution and especially the change of things such as work, which used to be governed by tradition but increasingly during the nineteeth century turned work into a commodity governed not by tradition but by the market.

Speaking now as a sociologist or cultural anthropoligist, the growth of market-based economies destroys traditional ways of organizing economic activities.

No question.

Still, in world B, Bill feeds a lot of people instead of just two. And if Joe isn't a barber by day, is his amateur haircut any good?

There's a value to specialization and scale.

Next question; I understand the components that go into calculating the GDP include consumption, investment, government spending, and exports minus imports. Aside from all the bailouts and QE, with the feds on a $1 trillion per year borrowing spree, doesn't that extra spending jack up the GDP? That money is entering the economy, right?

I would be interested to see the correlation between oil prices and GDP with borrowed government spending backed out. It seems like we should still count government spending from taxes, because that comes from real business activity. But I wonder what the correlation looks like with just the borrowing backed out?

It seems to me that government spending using borrowed money would be relatively insensitive to energy costs. So with the borrowing backed out I suspect the slope of the line in your first chart might get noticeably steeper.

Government spending is real, whatever the funding source.

The problem with debt instead of taxes is that it creates the impression that we have more money than we do: people hand over their money without realizing that it's not being invested, it's just being consumed. People think they're saving, when they're not.

To some extent it's a scam by the wealthy: instead of paying taxes, they get a t-bill, which is an asset.

Now, if interest rates go to zero, then that doesn't cost government much, but it's not a great way to do things. Taxes are better.

No, this does not count.

GDP is what is produced, which is the same as total income, which is the same as total expenditures.

Yes, this does increase GDP, according to the expenditure method of calculating GDP. In principle, the total production is the same as the total income which is the same as total expenses, so that's three ways to calculate GDP.

This is correct, however.

There must be proposals of what to use that would be a saner measure than GDP. For instance, GDP doesn't seem prepared to deal with the value of free software, which is not a trivial matter since it's integral to a whole lot of economic (and other human) activity. Having it is both real wealth, and a real wealth multiplier when it's applied in diverse enterprises.

The right software can keep a fighter jet in the air that otherwise would shudder and fall from the sky. Yeah, that burns a lot of fuel too. But even with that much fuel, you couldn't match the performance of that jet without the software. As the Wall Street meltdown showed, the wrong software can crash about anything, especially when used by gready idiots. But the right software, well used, gives us tremendous leverage. And the capabilites of software and the hardware it's on are growing exponentially even as energy supplies flatten out.

To what degree can that be a substitute arena for growth? And how do we come up with yardsticks that measure that sort of thing, prospectively or historically?

I believe there is a contribution to GDP from buying a new manufactured home (the GDP contribution is the sale price, not the builder's costs). Otherwise the builder's costs (and profits) count toward GDP. Buying a house (new or used) also results in contributions to GDP from closing costs and real estate commission. Occupying a house also counts toward GDP, as you are assumed to be renting the house to yourself and the imputed rent is counted as "produced."

Banking profits are included in GDP are they not?

Yes. All business profits are counted on the income portion of GDP. Caution! The "profit" reported is defined by the Internal Revenue Service. Most importantly it is quite different from what economists call "economic profit."

Parts of the oil industry get extremely favorable treatment from the IRS and report much less profit than most other industries.

Another dense question: Someone produces something, a widget, which someone else buys and uses. This production/sale boosts GDP. The widget wears out (or was 'disposable' item), and I get paid to make it go 'away' to the landfill. Does this transaction boost GDP, and is the waste stream (removing resources from the economy) counted as a reduction?

Another example would be discretionary uses of fuel for pleasure: I buy a boat and put fuel in it. These are counted as positives toward GDP. I use the boat, burning fuel for years pulling water skiers, but producing nothing (but emissions). Is this a source or a sink?

The waste handling service is counted as part of GDP. The waste stream as such doesn't affect GDP. That is, GDP is all about how much is made (income, in a way). Then how much of that that is retained, stored, durable (wealth, if you will) from year to year is quite another matter.

The gasoline is counted as a source of GDP (at least the part of the value that is not imported). It's all about how much value is actually produced. Measuring by expenditures works, but is a bit unintuitive. There are no real GDP sinks, I'd say, i.e. there are no negative components. (Sure, if you measure by consumption then you have to subtract any net imports, but that's just removing stuff that you shouldn't have included in the first place.)

Nominal GDP, however, is related (Keynesian view here) to increases in debt issuance. Past instances of increasing nominal GDP coupled with falling debt issuance has been aided by sharp rises in velocity. To argue increasing real GDP with falling nominal GDP, while theoretically possible and a common exercise given to 1st year econ students, is absurd in my opinion (given that such a large % of transactions in the real economy are aided by the financial system and the large body of research that points to price "stickiness" in the short run).

To assume that velocity will increase "just because", as the Austrians and Neo-Classicals seem to think, is rather dangerous IMO.

Greenie - You're obvious understand economic theory far better than this simple geologist so I'm curious of your view of this simple thought: increased debt and/or creation of monies by the Fed effectively lowers the "felt" price of energy. If I can't pay this month's mortgage and my brother loans me the money I can still maintain my lifestyle (i.e. spend money) as normal. So, poorly stated, my personal GDP hasn't changed. In fact, if I understand correctly, by borrowing the money from my brother I've increased my GPD?

Thus the negative effects of rising energy costs on GDP are reduced, to some degree, as a result of debt/money ceation used to offset decreased purchasing power. Somewhat akin to an old joke about my Cajun cohorts: why do you pay your coonass worker every week and not once a month? Simple: because for a short time after payday he the richest SOB in the neighborhood. And then the rest of the month he's the poorest SOB in the neighborhood. Today the US economy may be trying to reach some reasonable growth. But are we looking at those factors that may have helped us recover eventually will lead us to be the poorest SOB's in the neighborhood?

"But are we looking at those factors that may have helped us recover eventually lead us to be the poorest SOB's in the neighborhood?"

The short answer to your question is an emphatic "Yes!" Both fiscal policy and monetary policy have been aggressively used to increase the rate of real GDP growth. Fiscal policy means bigger government deficits, driven by tax cuts and spending increases by the U.S. federal government. The huge risk here is that cumulative deficts year after year after year tend to raise national dept to the point that the federal government cannot keep servicing (making interest and principle payments) on its national debt. Already the official debt numbers are bigger than the official GDP numbers. Probable outcome if debt goes to twice the size of GDP is double digit inflation. Possible result is hyperinflation which, in effect, wipes out all of old debt.

Monetary policy has been used aggressively by the Federal Reserve System to keep interest rates very low and and keep up the rate of growth in the money supply. QE1 and QE2 were examples of monetizing the federal deficit, which is essentially printing more money. Again, if aggressively easy money continues, eventually we will have much higher rates of inflation. By itself, monetary policy probably will not create much higher rates of inflation. But in combination with huge and growing federal deficits, what is going on is the Fed buys enough U.S. government bonds, notes, and bills so that the Treasury department has no problem selling all of the new securities that it wants to.

Something which many (perhaps most) economists do not understand is that where the big economic problem is high prices and declining production of oil, then neither fiscal policy nor monetary policy will work very well to stimulate real growth in GDP.

Thanks Don. I was afraid that was the answer. So my analogy to being "coonass rich" may not be far off. And yes...that's a recognized term down here. And to make it worse not only did he blow his paycheck but also borrowed some from a loan shark. Eventually you either pay up or get hurt really bad if you don't.

I'd like to point you to two charts:

M1: http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/M1?cid=25

M1 Multiplier: http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/MULT?cid=25

Though you stated earlier that economics has a "well defined vocabulary" I'd caution that this vocabulary and its definitions vary from school of thought to school of thought and its use varies considerably (in accordance with one's ideology) once one steps outside of academia and into "professional" economics. In the circles I run in, we define the money supply as the MV portion of the quantity theory of money (MV=PY where M is the monetary base, V is velocity... or the number of times money circulates through an economy in a year... P is the price level and Y is real GDP). Using this definition, the money supply hasn't expanded by that much.

Note that most of the mainstream media and the ads that you see on TV to buy gold only show you the first chart accompanied by "ZOMG!!! Federal Reservez Iz Printing the Monyz!!!" (sorry, had to use a bit of meme culture there).

First, I'd like to take issue with your statement re: higher rates of inflation. Japan has been at ZIRP for over two decades now and I'm yet to hear any tales (or see any data) of high inflation (let alone the hyperinflation predicted by so many). How do you reconcile your view of the Fed's monetary policy with the Japanese experience? (note: my only area of concession on this topic would be regarding the large capital inflows that regularly accure to Japan as a result of its large ownership of foreign assets. However, the U.S. experiences similar proportional inflows simply because the rest of the world doesn't have a better option. Europe is only exacerbating this. No, gold is not an option.)

With that said, your observation that the Fed on its own (given its current purview) cannot create inflation without Federal deficits is correct. Government spending is the transmission mechanism for the Fed's monetary policy. If we were to balance the budget overnight but the Fed were to maintain its aggressive bond buying, chances are we'd experience a severe deflationary shock despite the Fed's best efforts.

Your points are valid.

Mainstream economics has a clear and well-defined vocabulary. Austrian economics are outside the mainstream, e.g. in its definition of inflation as referring only to the expansion in the supply of money.

Japan has been in a period of stagnation in real GDP growth combined with a gradual deflation over the past twenty years whereby the yen gets stronger and stronger when compared with the U.S. dollar or the Euro. With its aging and declining population, Japan does not need real economic growth to keep real disposable per capita income about the same. Because of Japan's declining labor force they have been able to keep unemployment rates lower than the U.S. and much of Europe.

I do not think there is any likelihood of the U.S. balancing its budget overnight. That, IMO, is not something to worry about, because there is no political way for it to happen. Debt deflation was a serious possibility in 2008, and were it not for vigorous intervention by central banks, we probably would have had debt deflation as bad as the early 1930s. I think the chance of global debt deflation is very small during 2012.

During the past several years in the U.S. the rate of inflation, measured by the Consumer Price Index, has fluctuated but averaged out over the years has come remarkably close the Feds announced goal of 2% per year. Thus, as I read the data, the Federal Reserve system has gotten the rate of inflation that it wants. My WAG is that the U.S. rate of inflation will stay close to 2% until economic conditions (rate of growth in real GDP, unemployment rate) change, and when that happens the Fed will announce a new target for inflation.

In my opinion (and that of a huge majority of economists), the velocity of money is not a stable function. Milton Friedman, to his dying day, asserted that the velocity of money can be accurately predicted because it is a stable function. I do not know of any major economist today who claims to be able to predict the velocity of money.

@Rockman: I wish I could give you a simple answer but, unfortunately, it's a rather complex question. I'll do my best to deconstruct your question

The fed hasn't created new money so much as it has simply prevented a contraction of the money supply by increasing the monetary base. I'll point you to one article, two charts, and one graphic of my own creation:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantity_theory_of_money

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/M1?cid=25

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/MULT

http://www.flickr.com/photos/29144245@N02/6983223355/in/photostream

That last link, the one to my flickr account, shows the role of debt/money in the real economy. It essentially creates elastic contracts among firms causing/allowing them to specialize and trade (the source of the "wealth of nations", ex energy of course). Think of it this way: money is lubrication for the internal combustion engine that is the global economy. For the sake of the metaphor, let's just say that the roughness of the cylinder wall change over time (sometimes rougher, sometimes smoother) and this is representative of the efficiency of the economy. Right now, the economy is inefficient (too much investment into housing and associated products) so we need more lubrication if we're going to keep running at the same speed while we smooth the cylinder wall out (invest more into our energy infrastructure) Note that just because we have the lube doesn't mean that we will smooth the cylinder wall and that not having the lube wouldn't preclude us from smoothing the cylinder wall.... the lube just let's us maintain the status quo for a little while.

SO..... many capital intensive projects in the economy are financed through debt (I'm sure this is very true in the oil patch). The service of this debt is dependent on

1. Real production (barrels of oil to keep things relevant)

2. The price level (the price of a barrel of oil)

(The combination of these two items results in nominal GDP. If you talk to anyone in the bond business, they'll stress the importance of nominal GDP to aggregate debt service.)

The price of individual goods moves roughly in-line with the general price level. If you finance an oil well assuming oil >$80/bbl and there's a sudden deflationary shock and the price of oil falls to $30/bbl, chances are you're going to either produce at a loss, shut in production, or sell the asset. Assuming most of the other players in the industry are in the same boat financially, a sudden rush to the exit can disrupt supply as there will be a pause in drilling leading (eventually) to a decline in production relative to where it would be if the same rate of investment had been maintained.

So... yes, the Fed has sort of lowered the "felt" price of energy but only by facilitating continued investment in infrastructure and thus smoothing out supply. IMO, that's not really artificial as a "rational" economy would invest in its infrastructure in continuous fashion.

Mucho thanks Greenie. Economics in my end of the oil patch are relativey simple: NPV. Interesting about your oil patch analysis. Exactly how it works. Cash flow is KING for almost all companies. In the face of falling prices most will do what they can to increase production instead of cutting back. Even if that means they won’t recover their original investment. And what skews reality more than many realize that public oils will borrow a lot of capex for projects that have margin returns. The goal is reserve replacement to keep Wall Street supporting their stock. The many tens of $billions going into the shale plays certainly boost GDP to some degree. But for many companies the effort is not doing much better than swapping a dollar for a dollar. And in some cases, with current falling NG prices, maybe not even breaking even. If prices fall much further it may rival the housing bust. Booms are great while they last…but.

That's why I'm an advocate of using energy as a currency. Far less of an illusion.

You read my mind.

I agree totally, that as the low hanging fruit (of efficiency) is removed, this ability to continue growing without more oil becomes problematic.

And, even though you are looking at total world growth, the need for more oil per GDP is not even. Manufacture and export countries (china) have a much stronger tie to oil consumption that banking economies.

What's happening at the change of slope in Fig 2 is that increased price for fossil fuel is mostly bringing coal into play rather than oil. That increase in price is causing increasing amounts of fossil fuel to be burnt, but its coal rather than oil. It would be interesting to see just how much of that kick vanished if the plot was fossil Joules rather than just oil equivalents of liquids.

I think one would find that growth ex-oil would be a polynomial function over the long run (makes sense if you think about the diminishing marginal utility of technology, technology shifts, and investment periods).

IMO, the whole thing (the global economy and it's innumerable interdependencies) is too mind-bogglingly complicated to model with any precision. I doubt that the conclusions arising from a model (even a rather intricate and well thought out one) would be significantly more accurate than a simple regression.

You are making an assumption with that.

It's why whenever Greer gets mentioned I tend to throw a spanner, and why I chuckled when I saw that graph. Whilst more growth might mean more complexity, which might mean more energy; it's NOT set in stone and you can think of examples where it doesn't hold.

Similarly, when you come up against a physical law you might get diminishing marginal utility of technology - but it's not a given, and particularly not a given when you can change the technological basis by which you get something done to allow step changes in efficiency, resource utilisation, etc.

It's wrong of economists to always expect technology to come to the rescue, and insulting to think money is the magic factor that makes technology change happen. However it's also wrong to assume that no new technology, and particularly no new science will occur, or that improvements must always diminish over time till things reach a grinding halt.

The truth is somewhere inbetween - and frankly if it lies somewhere near 2% growth, that would work.

Sound and measured post

yeah it is a possibility.... thou I find it hard to imagine avoiding the pitfall of diminishing returns in medium term time-scales (ie this century)

2% growth in the current geo-economic climate could be construed as a special version of diminishing returns in of itself. Because as previous non players of the consumer game in the developing world are lifted out of extreme poverty in vast numbers this must result in a lowering of per capita prosperity in the OECD.

I think this is already happening. I also think it is a dangerous time politically because of it despite it being a form of rebalancing of world wealth. If you like that is the reason it is dangerous

the big if is a post early-mid century peak in energy[all sources] avoidable? Because if it isn't then navigating this earlier problem of wealth re-distribution will then face the challenge of a stall in the living standards of the developing nations. Part of this geo-political knot is very reliant on technology coming up with the goods... My instinct is that technological advances tend to be hyped.

take the internet.... good bad or meh?

The Internet by itself is not only good, but fantastic. Combined with mobile networks and handsets, it is hard to find superlatives to make it justice. It is and will be truly transformative, and especially for developing countries. 20 years ago, very few had used a cellphone and the web was in its absolute infancy. 20 years from now... who knows? Less than half-way, in 2020, in the vision/prediction of Ericsson, there are 50 billion connected devices.

impressive.

what sort of problems has it mitigated and what new problems has it created/exasperated ?

New problems - you tell me. Less privacy? Information overload?

Mitigated problems from mobile and internet tech:

* lack of good money transfer solutions

* lack of access to world encyclopedic knowledge.

* lack of access to price comparisons, weather data and so on.

* security issues (no access to parents, friends, 911)

* substandard communication in areas with little fixed line infrastructure

* lack of good ways to organize (especially in dictatorships, but also on topics such as PO)

* limited opening hours for information services, such as banking, tickets

* lots of people and offices needed for bureaucracy.

* high cost of communication.

... and so on. Most of the mitigation is "nice to have" in rich democracies. In poorer countries, it is truly transformative, as the difference in access compared to the unmitigated situation is so much bigger. Granted, smartphone penetration is low in developing countries, but you'll see.

I could get really into this but on reflection its Off Topic so maybe a drumbeat chat sometime soon when the opportunity arises

The Internet by itself is not only good, but fantastic

well that is putting a value judgement on it and of course those vary by perspective, but that is a minor quibble.

No doubt I felt the ground shift under my chair as I sat in front of a campfire with my first cell phone. The picture of that fire is still the wallpaper on the outside of my flipup. Cell phone spread (on top of internet connectivity) may not be as significant a step as learning to control fire, but considering the relative numbers involved there really is no way to compare the two events--they are both huge.

Yes, Greer's articulate anti-technology writing often misses the more likely ways that humans will respond in the future. His recent anti-machine articles have badly missed the way technology will be used in the future. As mididoctors points out, 2% global growth for a century would probably involve wealthy countries losing their relative economic dominance (or else an uglier scenario where the wealthy nations maintain their growth by repression.) And either of these may make it hard to avoid armed conflict. The future depends much more on what the humans choose to do that it depends on fossil fuel depletion or fundamental limits on technology. On this point Greer is often right.

No country which is long on resources relative to its population size will lose its dominance relative to countries which are short on resources. To this end Europe as a whole is more vulnerable than the United States and India is again even more vulnerable still with places like Egypt taking up position even further behind. To put in succinctly, in America the way of life is threatened and in Egypt the way to life is threatened. In a world growing long on people and short on resources, he who has resources and control of the spoils from those resources wins.

Two comments: First, the US currently uses roughly 25% of many global resources. We don't have 25% of the reserves of many of these resources, so by your metric, the US is likely to decrease its current dominance.

But your metric is also too simplistic. There are a vast range of choices that humans can make that make huge differences in the number of people that can be supported at a certain standard of living given a resource base. Parts of Europe are actively working toward a much less resource intensive society for a given standard of living. The US will likely enter the coming resource shortage with the public assumption that the 'American can-do spirit' can surmount any obstacle...even the law of conservation of energy. That will continue to delay effective responses and make a large decrease in the standard of living that our resources can support. I agree that Egypt is probably in a worse situation because its lack of resources is amplified by its social instability and recent terrible governance.

That's the hub of it

The vast range of options equates to political balkanisation..which is a real problem about how to "fix the problem"

Decrease in dominance yes, however they still have a LOT of resources available per capita and a relatively low population density as compared to other parts of the world. Europe has to work towards using fewer resources because they have fewer resources, hence their support of climate change policy. They want the world to follow suit in doing things that they have no immediate option to do otherwise. Having Canada right next door is of course another really good bonus as well, most other parts of the world are heavily over-populated relative to the north of North America.

I think perpetual economic growth on a finite planet is an absurd idea. That being said, 2% growth will probably not service the debts we took out on assumed future economic growth. When you build an unsustainable economic system or society, eventually reality comes crashing down on your parade.

perpetual economic growth on a finite planet is an absurd idea.

If measured in terms of resource consumption (goods vs services), then of course. Which is why there really isn't anyone arguing for it. Heck, car and appliance sales plateaued in the US and Europe decades ago.

As a practical matter, it's a strawman.

The current global economic system requires perpetual economic growth. I have never heard of a “services” economic model.

The current global economic system requires perpetual economic growth.

Where did you get that idea? It's really not true.

I have never heard of a “services” economic model.

You've heard the phrase "goods and services" - that's what it's referring to.

Site and example of a modern economy that does not require perpetual economic growth if you would and I may move there. The global economy goes into recession with a 2% growth rate. That leaves little choice but growth or collapse. That is the order of the day, what all countries are shooting for. I am at a loss how you could think otherwise.

I read your post again and saw that I misread your post. I thought you were proposing do away with the “goods”, leaving only the services. What economy would we have without goods and services? How do we grow the economy without consumption?

Site and example of a modern economy that does not require perpetual economic growth if you would

First of all...that's assuming the argument. For instance, the US does not require perpetual economic growth.

One important word here is "perpetual". This argument started with the idea that infinite growth is necessary. I'm not saying growth isn't needed for 30 for 100 years, I'm saying it's not necessary "forever".

Without economic growth the U.S. economy would collapse. The CURRENT system requires growth indefinitely.

But why? What evidence is there for this idea? What school of economic theory supports this? What is the best authority for this?

A counter argument: Japan has gone without growth for 20 years without collapsing.

“But why? What evidence is there for this idea? What school of economic theory supports this? What is the best authority for this?”

There is no current economy that can survive protracted recession growth rates let alone no growth. I do not understand how you do not know this. I am of no particular economic school. I have yet to find an economic theory that I think is sustainable.

Japan is taking debt against future economic growth. Should their financial system and economy slow to the point of not being able to pay the interest of this debt they will be in trouble. Try selling bonds as a nation with the caveat that your country will have no GDP growth.

So do you think that the Japanese have achieved a sustainable steady state economy? I think I am beginning to understand why you think peak oil is no problem. To say that Japan has had no GDP growth for the past twenty years is misleading. They have years where they grew GDP and years where GDP shrank. But make no mistake; the debt they incur is based on future economic growth.

There is no current economy that can survive protracted recession growth rates let alone no growth.

Well, I would have thought protracted recession growth rates would be worse than no growth.

Japan is taking debt against future economic growth. Should their financial system and economy slow to the point of not being able to pay the interest of this debt they will be in trouble.

That debt is owed to their own citizens - it's a wash.

the debt they incur is based on future economic growth.

Hmm. Kind've. Still, if they don't pay much interest, they'll still have....about the same level of economic activity.

“Well, I would have thought protracted recession growth rates would be worse than no growth.”

Slow growth rates would be worse than no growth? You do realize that a recession is just a slowing of growth don’t you. As I understand it recessions are considered a normal part of the business cycle, a protracted recession is considered a depression. That does not usually mean negative GDP growth, just slower growth. If a nations GDP is growing at 4%, then slows to 2%, that would be a recession. The current economic model, which is the only one I care about, needs growth. That is why the Japanese borrow more money. Japans debt to GDP ratio is now around 220% and growing. If that seems sustainable to you we again see the world very differently. Greece is a preview of what is to come.

“That debt is owed to their own citizens - it's a wash.”

So if the Japanese eventually can’t pay the interest on their GROWING debt, and default on bonds and loans, it will not matter? I really am wondering if you think the Japanese have a steady state sustainable economy. It sounds to me that is what you are implying. We eventually will find whether their economy is sustainable or not. When oil production starts to fall from the current plateau, I think the answers will come faster.

Cheers

a recession is just a slowing of growth

No, a recession is negative growth - in other words, declining production.

If a nations GDP is growing at 4%, then slows to 2%, that would be a recession.

No, that's just slower growth. Occasionally people will call that a "growth recession", but they're speaking loosely.

Greece is a preview of what is to come.

Greece has been defaulting on it's sovereign debts regularly every 25 years for the last 200 years. It's not that big a deal, except that this time the EU is forcing Greece to cut government spending very dramatically, which has been very painful (and probably counterproductive).

So if the Japanese eventually can’t pay the interest on their GROWING debt, and default on bonds and loans, it will not matter?

Not as much as you might think.

Have you read "This Time is Different - 8 centuries of financial folly"??? You'll discover that countries like Japan defaulting on their debt happens all the time, and is not that big a deal. Certainly not TEOTWAWKI.

This might clear things up for you

Here you go http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recession

I'm not sure of your point.

I note that the article says the same thing I did: a recession is a decline in GDP, not just a decrease in growth.

"The NBER defines an economic recession as: "a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy".

Did you have something particular in the article in mind?

“No, a recession is negative growth - in other words, declining production.”

GDP going from 4% growth to 2% growth is negative growth. I think this conversation has veered away from the topic and into arguments over semantics.

I will check out the book you mentioned.

Cheers

GDP going from 4% growth to 2% growth is negative growth.

Well, I don't know if it's important, but it may be useful to be clear about this: that's not negative growth, it's reduced growth. Growth is increase in GDP from year to year. If that increase continues, but is smaller, that's a decline in growth, not an actual absolute decline.

It's the difference between a derivative and a 2nd derivative, if that helps.

"It's the difference between a derivative and a 2nd derivative, if that helps".

True

"In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction, a general slowdown in economic activity" From Wikipedia. Reduced growth is a recession.

Reduced growth is a recession.

No, a "slowdown" isn't reduced growth, it's decline.

Going from 4% growth to 2% growth isn't a slowdown in activity, it's a reduction in growth, aka, a reduction in speedup.

If sales drop by 2%, that's a slowdown. That's a negative change, a decline. If they grew 4% last period and then grew 2% this period, that's still increased economic activity, but reduced growth.

See the difference?

-----------------------------

As the article notes, a generally accepted definition of a recession is a decline for more than one quarter in economic activity. A decline in absolute activity, not a decline in growth.

Having spent a few minutes looking at several definitions of recession, from several sources, it seems the prevailing definition would be 2 quarters of negative GDP growth in a row. Every different source seemed to vary. I will have to concede that your definition, upon reading several, is the more accepted view. A growth recession is what I was referring to. Investopedia says that negative growth is one aspect of a recession. Some economist prefer the definition of a 1.5% rise in unemployment as the definition of a recession.

Economic definitions which seem slightly open to interpretation aside, any country with a growing population must have growth to maintain the status quo in the labor market. Theoretically economies might not need growth. The current batch of central bankers and politicians are all beating the drum for growth. I get the sense that many of them believe growth is what man was intended to do.

“If sales drop by 2%, that's a slowdown. That's a negative change, a decline. If they grew 4% last period and then grew 2% this period, that's still increased economic activity, but reduced growth”.

I do see the difference. If you are growing and then you are growing slower, I still think that is a slowing down from where it was. The normal output growth for our economy is about 2 1/2 percent a year, and the Fed believes that 2 percent inflation is appropriate. So a reasonable target for nominal G.D.P. growth is around 4 1/2 percent. If we fail to hit this mark, unemployment can rise leading some people, like those who prefer the rising unemployment definition, to call it a recession.

I must say though, whenever I have a good old TOD discussion with you Nick, I always learn a thing or two. I appreciate your point of view because it always seems to challenge my assumptions, which I prefer over discussing issues only with those who share my outlook on the future.

I must say though, whenever I have a good old TOD discussion with you Nick, I always learn a thing or two. I appreciate your point of view because it always seems to challenge my assumptions, which I prefer over discussing issues only with those who share my outlook on the future.

Thanks! I agree - I'm always really glad to learn something, and having the other side to the conversation learn something is almost as good.

any country with a growing population must have growth to maintain the status quo in the labor market.

Sure. Remember, this conversation started around the question "is infinite growth necessary?". In other words, "does the economy have to grow forever?".

So, growth right now, and for 50-100 years, is a good thing. OTOH, it's not needed for 250 years, and there's really no reason to think it will. Population growth is likely to stop in around 50 years, and everyone's need for goods and services is likely to be satisfied within 100 years.

Here's a primer on a "service economy":

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Service_economy

FWIW, the current financial system (not economic) needs perpetual nominal growth. It does not need perpetual real growth (with the baked in assumption that people will tolerate lower buying power). The above statement/argument is seriously misinformed and has grown in ubiquity to the point where it's dangerous. Marx foresaw the end of the financial system that capitalism has (nearly) always employed but, unknowingly, lumped said system together with capitalism as if they were tied at the hip. They're not.

The Financial system needs enough growth to pay the interest on money borrowed on the assumption of future growth. I don’t think the Greeks are dealing well with the baked in assumption of lower buying power. They need economic growth to lift them from their current plight.

If the financial system goes, so does the economic system. But point taken, financial system is the correct term. Since I am so misinformed I will ask you to cite and example of an economy that does not need growth to avoid recession.

You missed a key detail: the Greeks are experiencing both a real and nominal economic contraction. The nominal contraction has destroyed their financial markets thus hampering the ability of the real economy to reconfigure itself and adapt.

Such an economy does not currently exist. To (crudely) borrow Taleb's example of the fallacy of observation (vs induction), just because we only see white swans does not mean that all swans are white. So, just because such an economy does not currently exist does not mean that it cannot exist. Again, I'll stress that it's important to divorce financial systems from economic paradigms/ideologies.

A view in mainstream economics is that recessions are the result of demand shocks. There are two ways around demand shocks in theory: nominal growth and negative nominal interest rates (interesting side note: nearly all schools of economic thought agree on negative nominal interest rates as a cure for demand shocks but usually brush it off in one sentence as "unworkable"). Only one has ever been tried in the real world: nominal growth. In theory, however, an economy could exist in a stable fashion with constant real productivity (no real growth), constant nominal GDP (no inflation), and negative nominal interest rates.

To understand the role of negative nominal interest rates in ending demand shocks you need to deconstruct a transaction in an economy where most money is the other side of debt. Let's use the classic example of a closed island economy with only two people: you and me. To make things simple, let's say that all items on the island are of equal value. Let's say I want to buy a knife from you. Ideally, we would trade right there on the spot but, at that moment in time, you don't feel like acquiring anything that I have. However, you don't need the knife and you like the idea of being able to acquire one of my goods in the future. So we create a contract. One side of the contract is a dollar of equity which you give to me. The other side of the contract is a dollar of debt which you hold (the debt is an asset to you, I have to give you a dollar to redeem it). You establish a time value for that debt... let's just say one year. You give me the dollar, I give you the dollar back, you give me the knife, and we're through with the transaction.... for now. In order for me to redeem my debt, I must present you with one dollar within one years time.

Do you notice anything about the above example? There is a distinct asymmetry in the time values of the debt and the equity. The debt has a ticking clock whereas the equity does not. If you don't spend your dollar within a year you'll force me to default. It doesn't matter how hard I work, how virtuous I am, or how appealing or suitable my goods are. The fact is, you have to spend that dollar in order for me repay my debt.

Let's transition, now, to the real world and consider the example of an individual (a 0.1 percenter) that has $100million in the bank. Most people would think that said $100million is just paper somewhere in a vault or 1s and 0s on a computer hard drive. Some people might have the insight to understand that that money has value because it is the only thing accepted by the United States Treasury for the payment of taxes. Most people do not realize, however, that the "assets" backing that $100million in cash is, in all probability, $100million in someone else's debt. In this way, said 0.1 percenter's cash is really a "call" on the goods and services of others. Currently, that cash doesn't earn much interest... but that's okay to said 0.1 percenter because it's plenty. It will last a long time. How would this change, however, if the cash carried a negative nominal interest rate? Clearly, the person would be more inclined to spend now for fear of losing it to nothing in the future. As long as said spending takes place in the same timeframe that the debt is due, debt service is possible. While I haven't defined the scenarios mathematically, it doesn't take much thought to reason that negative nominal interest rates on cash would be more likely to lead to spending in a time frame that would make debt service possible than if the cash had a zero or positive nominal interest rate.

In the real world, we have (previously) bestowed cash with a negative interest rate via inflation. However, there's a large body of research that suggests that the "veil of money" prevents consumers from seeing the real effect on their buying power (somewhat recent is the idea of "anchoring" value)

Green- thanks for the expansive answer. I post on this list to learn and have my assumptions challenged.

”You missed a key detail: the Greeks are experiencing both a real and nominal economic contraction. The nominal contraction has destroyed their financial markets thus hampering the ability of the real economy to reconfigure itself and adapt”

True, but when an economies financial markets are destroyed, is there any hope for the economic side? As I said earlier though, point taken on financial system versus economic system.

“So, just because such an economy does not currently exist does not mean that it cannot exist. Again, I'll stress that it's important to divorce financial systems from economic paradigms/ideologies.”

Absolutely right, but I am concerned with our current system, not theoretical possibilities. I think the world gets one chance to deal with the decline of fossil fuels and it will be with system in place now.

“A view in mainstream economics is that recessions are the result of demand shocks.”

I do not want to be rude, but I have serious doubts that mainstream economics is able to deal with resource depletion. There is no replacement for CHEAP fossil fuels for the free market to find.

“In the real world, we have (previously) bestowed cash with a negative interest rate via inflation. However, there's a large body of research that suggests that the "veil of money" prevents consumers from seeing the real effect on their buying power (somewhat recent is the idea of "anchoring" value)”

Good insights in my opinion. Am I correct to infer that you mean that money is lying dormant because of the “veil of money” misleading consumers of their monies declining value?

“As long as said spending takes place in the same timeframe that the debt is due, debt service is possible. While I haven't defined the scenarios mathematically, it doesn't take much thought to reason that negative nominal interest rates on cash would be more likely to lead to spending in a time frame that would make debt service possible than if the cash had a zero or positive nominal interest rate”.

That makes sense and again I think that is quite insightful. However when I look at the current levels of debt to GDP in the developed world, I see a mountain of debt that is growing faster than any financial system could ever hope to keep pace with.

Thanks for your response; it has definitely given me some research topics.

I think that the conflation of economic and financial arises [for me] in that the financial sector growth motor places a demand on the real economy to service it... or it is exposed as a hollow shame.

bubble economy.

From there a myth arises that growth is required to avoid collapse... interestingly by many colours of the ideological spectrum. Many anti-marketeers will cite a coming doomsday and market advocates always express a need for growth as it is the only way to enrich the entire population[they claim]. Yet on inspection I suspect they are more in favour of growth as it is the only way to enrich the poor without wealth re-distribution. Even this trickle down notion is suspect

The economic doomsday scenario is one I give "some" credence too because the separation of finance and the economy is a huge political battle with a lot at stake and the real economy will be stressed to meet demand.. The financial system does not operate in an isolated box and is part of the economic system.

YMMV

Midi- interesting thoughts that make a lot of sense to me, however I still feel that in the here and now, debt levels of modern countries force us into a growth paradigm. Again I can’t think of any current economy that could survive a protracted period of recessionary growth, much less the absence of growth.

It's not so much some posters may think this growth paradigm issue you talk of is wildly incorrect its more its a somewhat dated and simplistic caricature...discussion wise. I actually tend to agree with this simplification

But I feel the debate, here at least has perhaps moved passed this...

My inner doomer is not so much worried by lack of growth in its self but more the political processes of restructuring the narrative we are moving into.

If people were highly flexible to political and mandated behaviour change one could solve the worlds by decree very easily... oddly I think people are far more tolerant of extreme economic restructuring than many here and elsewhere imply. However tolerance of change is not a universal value across all issues or cultures...its an absurdly complex tableau of "stuff". Some of it real arcane BS centred around modern interpretations of late Iron age farming belief systems transposed on early industrial age nationalism.

our social machinery is being tested.

2% growth means double purchasing power per capita globally every 35 years?

And that is to be achieved with no greater use of energy and physical stuff than now?

(Increasing middle class in BRIC with a taste for more upmarket food and little cars, and we should not forget the oil exporters?)

So whither the USA? I can't see a big enough increase in low-paid servants, factory workers, and crop pickers?

Or do I?

BTW, Greer discusses the US Empire: expensive place to run. You might begin to see diminishing returns?

I assume you're replying to me...

1) there's an enormous difference between "perpetual economic growth" and growing for another 35 years, or 100.

2) Economic growth doesn't require low-paid servants, factory workers or crop pickers. In fact, one of the US's biggest problems is figuring out what to do with people who don't have a lot of education, but who are no longer needed because of automation.

As far as empire goes, I assume you're thinking that the OECD/US are exploiting oil exporters. Actually, the US would have been far better off if it had taken the appropriate measures to never become dependent on oil imports. Oil exporters have gotten an incredible free ride, in large part because oil industry investors in the US were unwilling to see their gravy train end.

We don't need oil - the sooner we kick the habit, the better.

Well not really Nick.

But you raise a number of points.

Maybe the anecdotes I hear about the US horticultural industry are just that?

The factory workers I was thinking of are the ones the US does not have. Your clothes come from China, your shoes from Vietnam, and etc? Not sure about your cell phones? US is still a big manufacturing continent, but proportions have changed with outsourcing to lower cost regimes, I believe?

For servants I was thinking globally. (That was what that 2% was referring to, i thought.) Middle class in India etc (even bigger numbers of them than in USA, these days?) have lots and lots of servants.

West Texas here on ToD tells us where the oil is going these days and about the shrinking proportion exported by some of the big exporters. I wonder what they are doing with it?

The USA certainly has got a challenge if you must grow economically with an expanding population on progressively less oil for the next 35 years. You'll be lucky IMHO. OK you might change your whole system of doing things: very good luck to you.

BTW, I see Britain where I live as being less well placed. We will always need to import the majority of our food as well in a few years almost all our energy and will need to find ways of paying the going rate.

proportions have changed with outsourcing to lower cost regimes, I believe?

Not as much as you'd think. The US manufactures 50% more now than it did 30 years ago. Further, I don't think outsourcing was really very good for the US.

Middle class in India etc have lots and lots of servants.

I'm not sure of your point.

you might change your whole system of doing things

That's not necessary. EVs are a drop-in replacement for conventional ICEs. Trains can replace trucks pretty seamlessly. Heat pumps aren't that hard to install, especially air-based ones.

Britain ... will always need to import the majority of our food

The last time I looked Britain produced 60% of it's food.

in a few years almost all our energy

It has pretty good wind resources...

If the growth formula is of the form R = a + bΔC where R is growth and C is oil consumption then indeed we can have growth when oil flatlines. The problem is what happens as ΔC becomes negative and increasingly so. When does oil decline start in earnest? I'd like somebody to plausibly argue the less oil with more growth case. In effect the drill-baby-drill crowd agree with this hypothesis.

Technical questions: what do the distributions look like? Were any distributions transformed into approximately normal distributions? F-test used for significance?

The incredible thing about Peak Oil is that just about everyone thinks it will happen. It's just when it will happen that they disagree on. But even the optimistic predictions would require immediate concerted action in order to stave off the problems that are coming.

1 in 7 people on food stamps in the US tells me more and says so much more than anything else. It is a recession leading into a depression when oil is over 100.

As for all of those coefficients and graphs and artificial stuff like that, well, liars figure and figures lie.

This is inline with DMU theory. There would be no way to obtain the data for an appropriate regression but, in my mind, we're dealing with an exponential function (e.g. 4% growth might require 2mbpd, 5% 3.4mbpd, 6% 4.9mbpd, etc)