Tech Talk - Future Russian Fuel Production from the Arctic

Posted by Heading Out on March 4, 2012 - 12:08pm

In the past few weeks I have been looking at the potential for sustainability in oil and gas production in Russia, now at a predicted recent peak of 10.36 mbd, when condensate is included. But the question increasingly becomes whether or not Russia can sustain these levels through this decade, as has been assumed by those suggesting there will be no supply problems in the near future.

In order to sustain this level of production against falling volumes from the current major sources in Western Siberia (estimated as 300 kbd in 2010), Russia is (so far) relying on bringing new fields into production in Eastern Siberia and Timan-Pechora, as well as having some increase in condensate as natural gas production continues to increase. However, as a broad generalization, these developing fields are at a size of about 500 mb each, with an anticipated maximum individual production level of around 150 kbd. Prirazlomnoye for example, which is coming on line has 526 million barrels in reserves, and will be producing at 132 kbd.

Since the high flow rates will likely not be sustained for long intervals, and declining production in Western Siberia will continue, Russia will need to continue major programs of development to find further fields to bring on line later in the decade and beyond. In addition, the declining production in other fields (which might increase overall decline in existing production to 5% or more, i.e. above 500 kbd) will add further pressure to sustain current levels, particularly given the criticality of oil and gas income to the Russian Government.

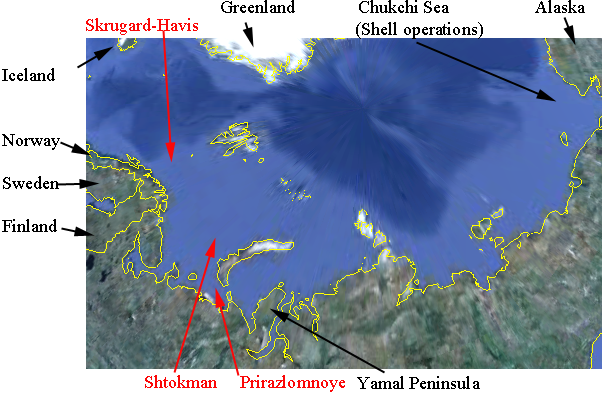

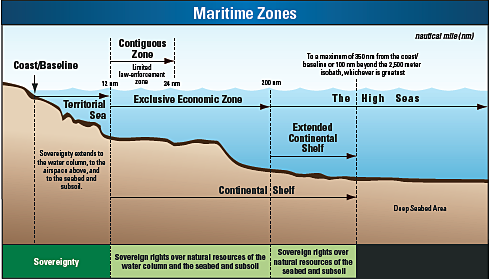

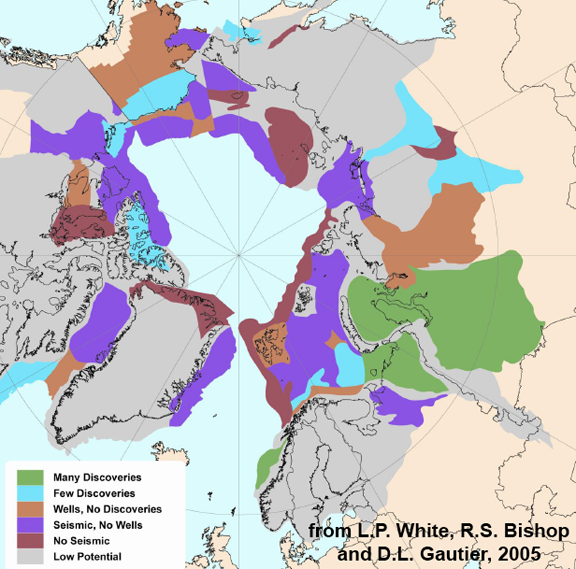

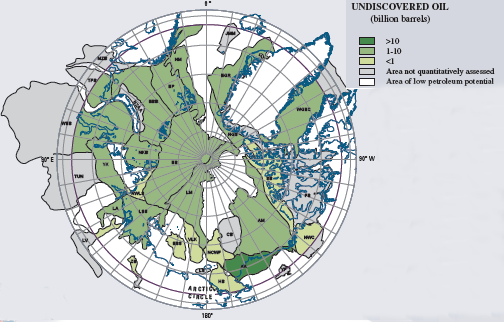

With much of the land already surveyed, the potential for large fields lies mainly offshore, and particularly in the various national continental shelves and the disputed underwater territory between them in the Arctic. This is a region where there are multi-national concerns and involvement, with the USGS having previously estimated that it is home to about one-fifth of the world’s undiscovered yet recoverable oil and natural gas resources, an estimate at the time of 44 billion barrels of oil and 1,670 Tcf of natural gas.

From the US perspective, the US Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement ((BSEE) seems finally willing to let Shell begin exploratory drilling in the shallow waters of the Chukchi Sea, although there has been a challenge to the recently awarded air Permit from the EPA. At the same time that the USGS is set to issue a new report projecting that shales on the North Slope may hold as much as 80 Tcf of natural gas and 2 billion barrels of oil, with initial drilling to prove the reserves anticipated to start this year. But those developments are on the other end of Russia, to the majority of current developments.

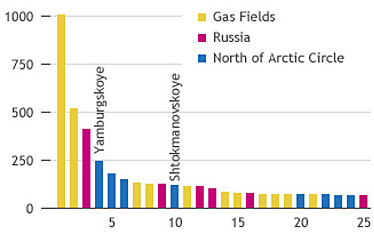

The recent discoveries by Statoil off the Norwegian coast and in the Barents Seas (at Skrugard-Havis, and Aldous Major South) show the potential that still remains in the North. Roughly a third of the world’s largest gas fields lie north of the Arctic Circle, with Russia having significant reserves among them.

Russia is therefore moving toward a planned program of development of the resources off its own continental shelf, where it is expected to be able to produce up to between 0.8 and 1.6 mbd of oil production and 18 to 20 bcf/day of natural gas. Part of the problem, however, is going to be cost. The new program is expected to cost some $216 billion at a time when the investments in developing the current projects in Yamal and Eastern Siberia are also demanding large investment, if those goals are to be met.

TNK-BP are spending $12 billion to develop the Russkoe, Suzunskoe, Tagulskoe, Russko-Rechenskoe, and Messoyakhskoe fields in the Yamal region, with the hope that these can contribute at the end of this decade, and into the next, at a total level of around 300 kbd. Suzunskoye is targeted to begin production in 2016, running at around 100 kbd once on line. Russkoye is projected to start in 2017, and produce 150 kbd of a heavier oil. Tagulskoye and Russko-Rechenskoe will come on line in 2019. Messoyakhskoe is a joint project with Gazprom (at $17.3 billion cost) and will not come on stream until 2024, at 320 kbd. These fields will, however, feed into the pipelines that head East, to China, Japan, and Korea.

Closer to Murmansk Exxon Mobil and Rosneft are exploring blocks in the Kara Sea anticipating that it may ultimately cost $500 billion to develop reservoirs in the difficult conditions with moving icebergs but for now expect that initial exploration and development will cost in the $10’s of billions.

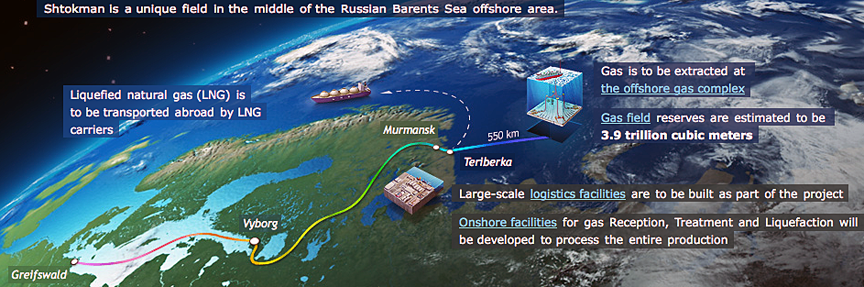

Of these fields it is perhaps the Shtokman natural gas field, which lies under the Barents Sea 550 km north of the Kola Peninsula, which has drawn most attention. Currently expected to start production in 2016, costs may well run over $15 billion.

Shtokman was discovered in 1988 (the name comes from Professor Shtokman who gave his name to the research vessel that found the field and contains an estimated 85 Tcf of natural gas, as well as around 400 million barrels of concentrate). It lies under 1,000 ft of water, with the interesting occasional problem of visiting icebergs that can weigh up to 4 million tons apiece. Planned to come on line with an average production of 2.3 bcf/day, half the supply is anticipated to feed into the Nord Stream pipeline for shipment to Western Europe (as the above map shows), while the rest is converted to LNG and will be shipped out by tanker. Gazprom has recently increased the area of its license rights for the field, with a new date for commitment set for this month.

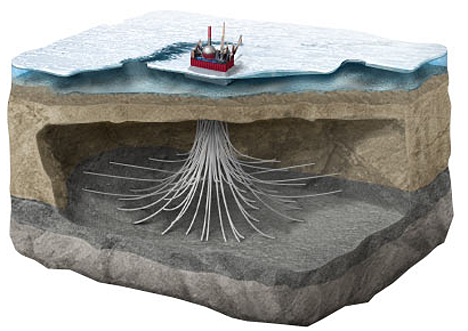

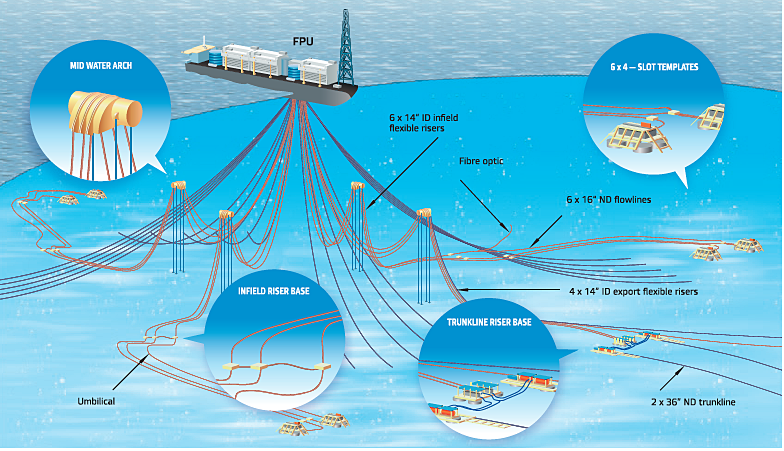

The current intent is to use a series of buoyed risers to connect from the wells to the surface, so that should an extra-large iceberg appear, the Floating Production Unit (FPU) can detach and move out of the way – should tugs not be able to divert it.

The pipeline shipments are planned to begin in 2016, but the LNG shipments (some 7.5 million tonnes a year) will not start until 2017. The project is a joint venture between OAO Gazprom, Total S.A., and Statoil A.S.A.

The USGS has noted that there are considerable regions in the Arctic that have, as yet, been poorly explored. In 2005 they produced this map of the then state-of-knowledge:

From this they produced two maps showing the location of possible undiscovered deposits. The potential undiscovered oil deposits are shown below:

However, the point is not that there is going to be no more oil; it is just as the production schedules above illustrate, that it is going to be slow and expensive to develop what remains. Over the next decade Russia will have to bring three or four new fields on line each year at around 100 – 150 kbd each, if it is to sustain production at current levels. It is somewhat difficult to see them being able to hold to that schedule, even for a year or two.

All I have to say is "track record."

363 million barrels vanishes in northern Yuzhnoye Khylchuyu (link)

Thanks for the information, if you follow some of the leads in that post you will find a story from RT that has some embedded videos of conditions in the drilling rigs in the region. It also gives some idea of the living conditions where everything in the summer has to be moved by helicopter.(Except for the reindeer tied up outside the tepee).

You are welcome. I'm surprised this news hasn't had more attention.

I second the thanks for the link. It really needs wider circulation.

And thanks to HO for the article.

great info Heading out,always look foreward to your posts.....r.m.

Canada has recently completed it's review of filing requirements for arctic offshore drilling (in light of Macondo well blowout in Gulf).

http://www.neb-one.gc.ca/clf-nsi/rthnb/pplctnsbfrthnb/rctcffshrdrllngrvw...

They agreed to keep in place their "same season relief well" (SSRW) policy, which they were thinking of repealing prior to Macondo well blowout. Greenland Oil Industry Association has petition to remove SSRW requirement drilling in waters near Baffin Island: "Same season relief well (SSRW) requirements will not be practical to implement in many future drilling scenarios, with limited open water seasons. Capping devices provide the fastest method of stopping flow from a subsea blow-out and should be part of normal Relief Well" (here).

Do you have any information on Russian requirements for SSRW in arctic drilling?

Excellent diagrams showing how these work and the locations, looks very complex and in a very harsh climate. I hope that everything goes smoothly and there are no accidents or spills.

Many people I've spoken to about oil/energy say that it's no problem because new discoveries will be made and new production in places such as the arctic will keep things going indefinitely. I have trouble understanding how most people can deny limits to how much energy is available when their evidence is that we can always find additional reserves as current fields deteriorate. The deterioration of existing fields tells me that all fields will deteriorate and there is only so much area to explore for energy reserves.

Drilling in the arctic looks like scraping the bottom of the barrel for the last remaining bits of energy so that it can be burned perusing frivolous activities such as driving to the mall to buy a plastic pumpkin.

What is the chance of Russia being THE dominant fossil fuel producer in 20 years?

1. They have vast areas of land

2. They have found huge amounts of fossil fuels on their land so far.

2. Their FF industry has generally been led by inefficent bureaucrats- which suggests they may have left a lot in the ground

3. They have great exposure to the arctic

4. They have historically been an empire under the czars and communists- which suggests they may find ways to regain the former Soviet Union either directly or through puppets- this will add more land and resources

5. They have nukes and won't be easily invaded by someone looking for their resources

What is the other side of the argument? Why might Russia not be dominant in 20 years? Where am I wrong? Any Russia experts out there? - thanks

The Russian environment can only take so much. The Aral Sea is mostly dried up. Gone are it's prosperous fishing industries, and sustainable agriculture too (from decades of soviet planning and cotton crops polluting surrounding lands with fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides). Lake Baikal, once thought too large to ruin, is currently threatened by industrial complexes in north and south, and agricultural runoff from Selegna River. Sites contaminated with radiation abound in Kazakhstan and the Urals. The Volga and the Baltic Sea have their own problems. And now Russians want to add the arctic into the mix. Russian dominance in energy is a boom and bust cycle, and nothing more. You need accountable government, a separation of powers, and wise investment to leverage resource booms into a sustainable economic future. Otherwise, you're just a greedy horde, and Russia is looking to perfect the model (and much to the short term benefit of the rest of the world).

Twenty years, maybe ... but 50?

The technology deployed to get at the stuff is so amazing when you think about it, but just a reflexion or projection of the supply stress, really not going to be pretty ...

Yes- it is always good to remember how well the Russians can foul their own nest. I did think of one other advantage, however, after my initial post. Because their population is declining, they may be less subject to the increasing pressure exerted by the export land model. Arab nations may find they have to choose between exporting or riots from their exploding population of restless youth. Assuming Putin can keep domestic consumption from growing they should be well positioned. The bear may yet rule.

The problem is the population is not declining anymore:

Unless offset by immigration, Russian population must inevitably decline some decades from now if its fertility rate continues at 1.6.

http://www.google.com/publicdata/explore?ds=d5bncppjof8f9_&ctype=l&strai...

The one thing that stands out in the posting is there's an tremendous amount of capex required for exploration/extraction - the source of which I think will dry up before long and the very reason behind any arctic endeavor evaporates. The capex funds are from those of us who need unfettered, affordable personal transportation in a 6000# vehicle with one occupant, though I exaggerate slightly. Affordable being key, however.

Even if there's a significant change in how we view, and consume oil - that is, we magically wise-up and realize there's no more driving to be done - it seems unlikely to me that there would be any future incentive to drill the arctic in hi-tech the manner detailed in the posting, at least not until it's the only oil left in the world.

Not only capex but the need to attract it by hyping the amount of oil. Did anyone really think the Yuzhnoye Khylchuyu field had over 500 million barrels or did they have to say that to attract investors? Either way at some point it turned into only 145 million barrels.

Over the next decade Russia will have to bring three or four new fields on line each year at around 100 – 150 kbd each, if it is to sustain production at current levels. It is somewhat difficult to see them being able to hold to that schedule, even for a year or two.

Any Bakken or Eagle Ford type shale plays for the Russians or haven't they had to scrape the bottom of the barrel hard enough to look for them yet? Certainly would seem a tad easier to manage those operations than arctic offshore, though even growth on Bakken scale wouldn't match the full decline.

A really silly, almost OT question. When drilling wells such as in the first diagram how does the drill turn the corner? i.e. How is a curve introduced into the drill hole?

It's puzzled me for more than a year now. Thanks, Alex

don't have time to look right now, but HO did an entire tech talk series that explained that and many other technical aspects of drilling for oil. It is well worth reading. It seems it was about two years ago, but I could be off on that.

Thanks Luke!

Moreati:

You can find the directional drilling post here, back in 2009 .

There is also an earlier, and slightly different post on the topic back in 2005 .

moreati - This may sound like a silly answer but this is how it works in very simple terms. Imagine you're pushing a long straight stick into some soft mud. Now imagine putting a small bend on the leading edge of the stick...just a few degrees off of straight. Now push the stick straight down and it starts to deflect in the direction of the bend. Now use a very flexible stick that will follow the path that the bend "drills". And as you change the orientation of the bend you change the direction of the hole. On the end of the drill pipe in a directional well is equipment with such a bend.

It won't look like it because of the scale of the illustrations you see but most direction holes don't change much faster than a few degrees per hundred feet drilled. And yes...drill pipe is easily that flexible to bend a full 90 degrees over even an interval as short as a 1,000'. There are different systems we can control from the drill floor that change the orientation of the bend (we actually call part of the down hole steering system a "bent sub".) And not only point the bend to make the hole go from vertical to horizontal but also left or right. How much control can you have? I have a lot of "geosteering" experience. I once landed and drilled a hole in the top 3' of a reservoir that was over 11,000' deep. One big help is "LWD"...Log While Drilling. We have devices just behind the drill bit that show a "picture" in real time of what we're actually drilling. We then adjust the bend as needed. If I have very accurate location data I can put a drill bit through a 5'X5' target at a depth of 3 miles. Amazing technology to say the least.

One of the aspects of any work in this area is the sheer remoteness and harshness of the area. There is no road access to the north coast; once you start to travel away from the last sizeable urban areas, roads stop. Any land-based support centre for arctic operations faces a huge logistics supply problem itself. Frozen rivers are used in winter and navigated by boat in summer. There may be a stabilisation of the Russian population, but like many of the other European countries, this is largely driven driven by immigration, legal or otherwise, and that is always a contentious issue. Furthermore, the shift away from the land to urban areas means that remote towns and villages become more remote with each year. It is a tough place to be.