Thoughts on a Sustainable Human Ecosystem

Posted by Rembrandt on September 19, 2011 - 10:19am

It is clear there are limits to the pollution a given ecosystem can absorb, the level of resources that can be depleted, and debt that can be incurred. Despite concerns of many about these limits we are far from tackling any of these problems on a meaningful scale. The question is why this is the case and if we (the Human Race) have the knowledge and capability to live within such limits on Planet Earth?

In this post, different modeling approaches to gain insights into sustainability will be discussed. We hope that readers will contribute their thinking of what a sustainable ecosystem would look like, and how to map the road towards it. One of the parts of this post is the initial outline of a project to model a human ecosystem from cradle to grave. This project will be carried out by the Institute for Integrated Economic Research (IIER), an institute in which Nate Hagens and myself are involved. Also IIER is looking for individuals to participate in this project, and encourages anyone with a passion for working on resources and energy consumption to take a look at our job advert and contact us via recruiting at iier dot ch.

Can a sustainable world be achieved?

The question of sustainability at a global scale can be difficult to fathom. In the case of ecosystems the size of damage done in past decades to centuries is immense, relative to the original state these ecosystems were in before the industrial revolution. For example, between 1950 to 2003, around 29% of fish species that are frequently caught today had collapsed, defined as their catch being 10% below the recorded maximum (Worm et al. 2006). The trend of this problem is many ways similar to non-renewable resources such as oil depletion, in that first the best available and cheapest resources are depleted. Historically, the big fish in the rivers on land were depleted first. In Europe this already occurred in the Middle Ages. Subsequently, the large fish near the shores, then further offshore, then the arctic, the shallow waters, and finally the deep sea. About twenty to thirty years ago we began to deep fish the ocean at depths of 1 km below the ocean surface in order to continue catching sufficient fish (Roberts 2007). This pattern does not imply that there are no longer fish in the rivers or offshore, but that the number of fish and their size is much smaller than before, and that a large portion of species have ceased to exist or are dying out. More importantly, at a global scale there are no new regions to explore in terms of fish catch today and the total number of fish caught began to plateau in the 1990s. It is likely that the total catch will decline in the not too distant future if the worlds fisheries continue to collapse at a rapid pace. The big question is if we are able to prevent this from happening, can we maintain the fish catch at today’s level, or at least not let it decline too much, by better management of fish stocks globally. So far global agreements to regulate fishing and to protect stocks have failed to make a substantial impact, notwithstanding the success that has been made in some cases locally. The reason is fairly common for all the 200+ global agreements made today, when they come in effect the actions posited in them are often not implemented, at least not at a sufficient scale. This because sanctions are not a part of such agreements which makes non-compliance the norm. Many reasons can be found for this type of behaviour, one example being the tragedy of the commons as first described in detail by Garret Hardin.

The lack of proper management of the world’s non-renewable and renewable stocks underlies what I think is part of general behaviour of the human species. We are not capable to deal with these problems by consuming less, or only with great difficulty. At an aggregate level because this would impact our path of economic expansion, at a disaggregate because it effects the wages and income of people (fishers in the example above). We as humans are best at solving a problem by developing new technologies and practices to fix one part of the problem. It is very unlikely that this will continue to work, as you cannot engineer your way out of depletion in the long run. For instance aquaculture as a technology in our fish example can help, but this is not a solution at the global scale of fishing today. For several fish species it is more profitable to catch them in the wild and deplete these stocks first before switching to aquaculture (Koldewey and Martin-Smith 2009), because of which the present lack of global regulation and sanctions imply a continuance of wild-fish depletion.

In light of the above, the solution to achieve a sustainable human ecosystem lies in developing solutions beyond more than technological change, but also into regulation of extraction to sustainable levels (which means consumption). The question is how to achieve such a sustainable human ecosystem, a system wherein all material and energy flows can endure, instead of being either exhausted or accumulated as waste. Can this be done at a global scale? Probably it cannot, at least not at the level of welfare that we enjoy today in OECD countries, but we can make meaningful attempts at a smaller scale of cities and regions to take important steps towards such a future. To do so we have to further develop the knowledge and capabilities to know which steps to take.

Approaches to understand what a sustainable world means

There is a common tendency in our industrial society to see solutions in terms of technological solutions. Many advocates of a sustainable world also adhere to this belief, one notable example being the plans outlined in Plan B (PDF). In this book Lester Brown, President of the Earth Policy Institute, outlines technological solutions and their cost to tackle a large number of problems such as deforestation, decreasing biodiversity, and lack of health care provision in developing countries. He ends the book by summing the cost of all individual solutions resulting in a figure of 187 billion US dollars needed to “restore the earth”. The problem with this approach lies in the lack of integration of problems and their effects. Not only of the effects that these problem have on each other, but also the solutions which influences other problems than those they intend to tackle. For instance, consider the problem of exhaustion of the seas fish stocks. By consuming less fish to reach sustainable reproduction rates, demand will be shifted to other food segments, for instance meat or beans as an alternative protein supply, where other problems may emerge. For each alternative such trade-offs need to be considered. The solution to waste can be an increase in the rate of recycling, by separating materials and collecting them from households, but this will substantially increase transport movements as each waste stream needs its own transport chain. Similarly, the production of cadmium-telluride thin-film solar cells can reduce the amount of fossil based electricity, but will also produce a lot of toxic components that need to be dealt with (Fthenakis 2004), and so on.

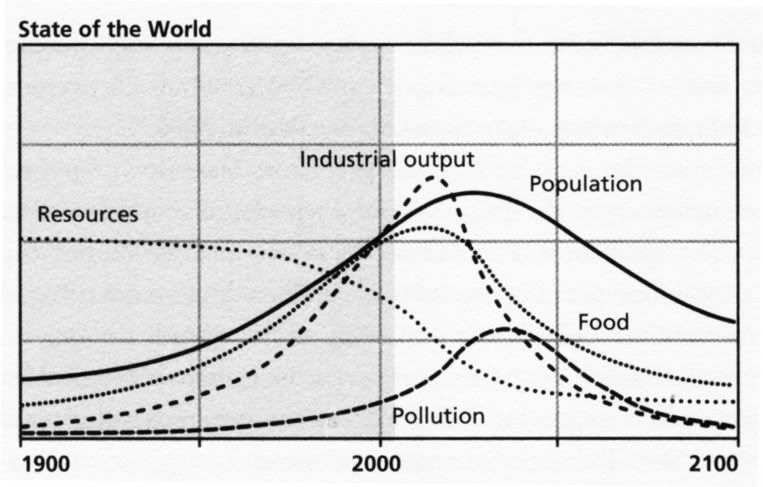

To deal with these, increasing use is made of integrated models that look at different scales, including resources, energy, population, environment, and economy. These models are often not built to investigate what a sustainable system looks like, but assess how the present growth based system we have is affected by steps that are seen as part of a more sustainable system. For instance, the PRIMES energy model used by the European Union gives a full picture of energy consumption and production within the EU, and allows for application of different technologies as well as environmental regulation through taxes, permits, and subsidies. The way in which these models are used in policy are therefore to explore different options under the conditions of today’s society, still assuming that the solution lies in obtaining technological solutions. There is little there in terms of halting certain activities, or choosing for radically different technology options which may be bad for short term economic growth, but beneficial for long term maintenance of welfare as their impact on the environment or resource exhaustion is low. Such roads plausibly have to be taken, as can be learnt from global models that map the problems at an aggregate level. The best known of such models is the Limits to Growth developed for the Club of Rome. Many others have been developed since. For example, the most advanced of such a model today in terms of ecosystems modeling is the GUMBO model developed by the University of Vermont, which maps changes at a global level in key indicators of ecosystem services, including soil formation, water availability, and climate regulation, and hooks these up with economic and energy activities.

To summarize, we have many models that only map partial aspects, some that map a more integrated world but still operate without sufficient reality checks, thereby losing the goal of a sustainable human ecosystem, and finally global level models which focus on aggregate development trends, but these generate little in terms of clear solution pathways. The challenge today is therefore to work on models that are able to provide clear answers to what needs to be done within the constraints of what is physically feasible, at local, national, and international scales. The question is how to go about to achieve this goal? In the remainder of this post we will look at one possible approach, informed by a project in its early stages of the Institute for Integrated Economic Research (IIER).

A framework to map a sustainable human ecosystem

The objective of a sustainable society is to establish an environment that is stable and resilient in the long run in several ways:

• From a perspective of resource availability, both renewable and non-renewable;

• In the sense that no agent or group of agents or location ends up accumulating resources in a way that is unsustainable for others;

• Equally, exchange with entities outside the boundaries needs to be balanced to avoid long-term instabilities in any one direction.

Under these conditions the key to understanding what a sustainable human ecosystem looks like comes down to mapping all resource flows through the economy and its connected ecosystems. The mapping of an entire “economic system” including all relevant exchanges and processes allows for looking at various complexities and interactions. Any intervention in the starting state of the system related to the required sustainable conditions can then be examined as to determine what both feasible and best solutions are. It may seem like a gigantic undertaking, but this is not the case when taking a limited geographical scope and through some simplifications. It should be feasible to limit the description to those processes and outputs in a society which produce approximately 90% of vital outputs, and assume others without detailed specification, as long as they do not form vital inputs that could stop other key delivery systems from functioning.

We strongly discourage modelling the “economy” of such a world based on money, but rather on physical interactions between participants and systems – which can later be complemented with a monetary component. That way, distortions from market imperfections – for example the insufficient assignment of a price for externalities – can be avoided. Thus, instead of using money as the baseline, we suggest modelling the entire “economy” on a non-monetary basis, but with the assumption of money being present as an enabler of simple and smooth exchange between agents.

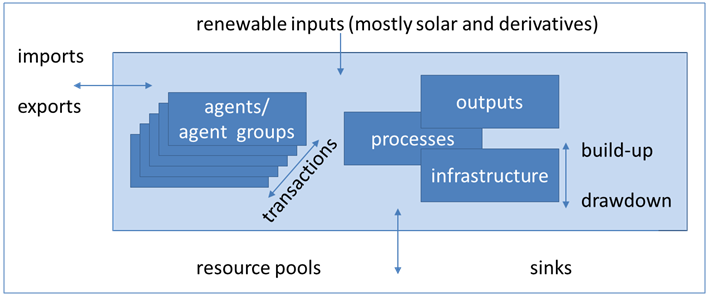

The key components to achieve a view of the entire economy are inputs, outputs and transactions which get shifted between physical entities (sub-locations) and agents in the model. Transactions can be processes, services or other exchanges (trade). The outputs and inputs can end up as infrastructure, in usable or non-usable resource stocks, or as pollution in connected ecosystems. The flow that these components create should be built in a way to allow for “imperfection”, as humans make errors and natural events can result in resource losses. This both in the availability of inputs (for example sunlight, wind, water), but also in the process stages, where human error and excess waste are rather the norm than the exception.

More details on each of these components can be found in the 9-page overview project document.

The modelling of these components based on a given system such as a city, region, or country, allows for tracing all type of flows and stocks within the human ecosystem. We can then see what happens if one stock becomes depleted or when pollution accumulates.

To get a grasp for the level of wealth and required changes are to achieve a sustainable human ecosystem, we need to adapt the model to be able to work with different degrees of cycling as one key condition. In a 0% scenario, no cycling takes place and all waste and losses of the processes go into sinks. In a 100% cycling situation, the society is not allowed to lose more resources and energy than can be harnessed or cycled. This provides a tool to map the road towards a sustainable human ecosystem, which is more important than knowing what such a society plausibly looks like, as the goal is to derive insights in what steps need to be taken. In most cases, the final reality of such a newly created ecosystem is not one of full cycling. Some inputs – like fossil fuels – might still be present for extended periods and thus used, and in many cases full cycling cannot be reached because of thermodynamic limitations.

The challenges to modelling

The framework above should allow for understanding the present reality that underlies the chosen geographic “economic system”, what a sustainable version of that system would like, and what a plausible road towards that sustainable system would be. The key challenge is to properly catch the boundary conditions of the model, and within these conditions understand what the essential variables and their interrelations are, as to resemble the real world as best as possible without introducing too much complexity. We think that with today’s knowledge this can be done, but acknowledge that there are still many uncertainties that will remain despite best efforts. Therefore, our intent is to take an open source approach to the modelling, so that remaining uncertainties can be narrowed down over time through the contribution of many people.

We encourage readers to contribute their thoughts as to what they think about the framework above, and what their thoughts are on the main parts that need to be mapped to understand what a sustainable human ecosystem looks like, within the scales of resources, ecosystems, economy, and energy. We hope that by this modelling effort we can contribute to new insights on the road to a more sustainable human ecosystem, and for those interested in working on this project to take a look at our job advert and contact us via recruiting at iier dot ch

references

Fthenakis, V.M., (2004). Life cycle impact analysis of cadmium in CdTe PV production. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 8. pp. 303-334.

Koldewey, H.J., Martin-Smith, K.M., (2009). A global review of seahorse aquaculture. Aquaculture. 301. pp. 131-152.

Roberts, C., (2007). The Unnatural History of the Sea. Washington: First Island Press

Worm et al. (2006). Impacts of Biodiversity Loss on Ocean Ecosystem Services. Science. 314 (5800). pp. 787-790.

Rembrandt, enormously ambitious and complex. I'm not sure it can be done. It requires great foresight to anticipate and predict all connected outcomes of one action.

Scottish wild salmon stocks have been in long term decline - who knows there could be a natural cause for this linked to shifting patterns of ocean currents. However, one human response to this was to introduce salmon farming in the 1970s. This has grown to become a major industry. In Scotland most of these farms are located on the west coast in sea inlets called sea lochs. Normally there is a small river draining into the head of the loch and 30 years ago these were teaming with wild salmon, sea trout and black eels.

The intentions of salmon farming were I believe good - aiming to save the wild salmon from extinction due to over fishing. What has happened is this:

1) High concentrations of fish lead to high concentrations of parasites and disease to the detriment of the wild fish stocks

2) Escaped farmed fish mix with the wild fish corrupting their finely tuned strain specific DNA that enables fish to navigate home to their home river (maybe)

3) The fish are sometimes fed on fish meal - meaning that certain other species like eels are being hoovered out of the ocean to feed the salmon - with bad impact on certain sea bird stocks and so on.

Wild salmon and sea trout stocks have become extinct in many of our west coast rivers.

Rembrandt,

I think it can be done. Yes it is ambitious. Yes it is complex. But there is already an enormous body of data on the natural world and human manipulation of it. The data needs to be reorganized into a form that supports the construction and testing of the model. Definitely will require more than a few people and more than a few months. As I say elsewhere, it should have be initiated back in the mid 50s, but it wasn't. And, if it really cannot be made to work, we will have learned not to try the particular approach taken again and some idea why. But the project really can't be abandoned unfinished. That would be a true collapse of civilization.

About de-emphasizing prices and money costs: A model that is built on physical transformations, stocks, and flows as you are planning can always be rewritten as a set of linear equations for a sufficiently small range of the system variables. The dual of that linear model will tell you what the prices will be if the real system actually takes on those values of the physical variables. One learns how economics is caused by physical reality.

Cheers.

The thing that modelers need to understand is that damage to the world's ecosystems began long before the industrial revolution. They began back in the days when hurter-gatherers were still small in number (fewer than 100,000) and even at that, could wipe out whole species of large animals. In fact, some say that the sixth mass extinction began 100,000 years ago. It was made worse when the world transitioned to farming, about 10,000 years ago. And, of course, the industrial revolution made it worse in the last few hundred years. Read more about this in my post, European Debt Crisis and Sustainability.

I think that what the modelers will find is that there is virtually no solution to a sustainable human ecosystem. Somehow, it is necessary to change man's nature, in terms of taking all he can, at the expense of ecosystems. With man's ability to use tools (such as nets for fish, and bows and arrows, and guns, and all kinds of modern devices), man has such an unfair advantage over ecosystems, that the system is headed for failure. Unless the model addresses these issues, I don't think it really adds to the world's knowledge base.

This is a very interesting question - will there ever be something like a truly sustainable human future? But to be honest, the objective of this project is not to start out with the assumption that because we've been unsustainable for a long time it doesn't even make sense to get to a better understanding of HOW sustainable our societies are and may become.

The final objective of this undertaking - and we know it is ambitious - is to create a macroeconomic view that hasn't been accepted broadly: that our ecosystem is as finite and as driven by energy and resource conversion as any other ecosystem, and to find out how that translates to a better understanding of reality.

I agree that there is no solution to a sustainable human ecosystem, however I doubt that the modelers will ever admit to this even if they finally come to that conclusion.

The problem is in our nature, not just in our human nature but in our animal nature also. We are competing with every other species on earth for territory and resources, and we are winning... big time! That is the way it has always been ant the way it always will be. It is the height of ignorance to believe that human nature can ever be changed.

And while we are easily winning the battle with other species for resources and territory, we are also competing with each other for resources and territory. There will always be The Haves and the Have-Nots among people within a country as well as among countries. And the have-nots are always trying to have more and the havs are always trying to increase their lot also. We are always in competition with each other.

Books are published on what this struggle is doing to the environment. Models are made and Plan Bs are proposed, but nothing really substantial is ever really done. Books and models are useless unless you can get almost every person on earth to change their behavior. Lotsa luck with that one.

Ron P.

Edo Japan was fairly close to sustainable. And SOME Pacific islands were sustainable IMO.

Fish from the sea renewed land trace minerals, etc. Population control by several means. Limited trade with distant islands.

One island decided to slaughter all the pigs for sustainability reasons.

Absent Climate Change, or a super typhoon (if the island was in that range - not all are), they appeared to be sustainable.

Other islands were not.

Alan

Surely you jest. Japan is the furthest of nations from sustainability. The world’s biggest importer of the fuel will take delivery of 131.4 million metric tons (of coal) in 2011, up from 125.3 million tons in 2010. Japan imports almost 100% of its coal, oil and gas.

The Japan Syndrome Japan, a country that today imports 70 percent of its grain.

Japan imports all of its energy and 70 percent of its grain. Now Alan, you just don't get more unsustainable than that.

Gad! It gets even worse. Overfishing is killing the ocean and the Japanese, by far, are the worst offenders. Their whaling fleet is driving the beast into extinction. I could post a thousand links about what the Japanese are doing to the ocean, killing off all fish, whales, squid and around their home island, the dolphins. But you Alan, see only the positive side, they will renew trace minerals in the soil. Really now.

Alan, think about it man, Japan has a population of 128 million. Not the most densely populated nation but considering that their island is so mountainous they have 12 people per acre of arable land. There are some much smaller nations with more people per acre but of nations with a high population that is the highest by far. (Except for South Korea which has a slightly higher population per acre of arable land.) Japan has over four times as many people per acre of arable land as India and 1.6 times the people per acre of arable lan as Bangladesh. Arable land > hectares (per capita) (most recent) by country

Japan is perhaps the most unsustainable nation in the world.

Ron P.

He said "Edo Japan". That is, Japan between 1600 - 1850.

Furthermore, modern Japan has all that it needs to survive, which is an appreciation that the critical resource is knowledge, and that the means to exploit knowledge, that is, the acquirement of skills, is the first order of business.

Hydrocarbons have been the low-hanging fruit, a resource we learned how to exploit following the onset of the scientific revolution. We are in the first stages of moving beyond hydrocarbons and I have no doubt that the Japanese will be among the leaders in the transition. They will continue to trade for foodstuffs, minerals and whatnot, offering products useful to farmers among other goods and services.

It continues to amaze me that some who claim to understand evolution, i.e. adaptation, fail to appreciate that our brain is both the result of evolution and the means of our continuing adaptation to an everchanging environment.

You must be a Julian Simon fan. It was his theory that human knowledge was the "Ultimate Resource" Simon believed that we would never run out of anything, that we could recycle everything.

Dr. Albert Bartlett on Julian Simon

But back to your post:

Yes, we did not leave the stone age because we ran out of stones. The Japanese will just transition to "something else". And just what will that be? They have only a fraction of the land required to grow enough food to feed the nation so they have no land to grow energy. But they have knowledge! Can they turn knowledge into energy? From someone who claims to understand evolution I am saying that knowledge will never evolve into energy. We get energy, fossil energy, from the earth. There is no replacement. And for a small overpopulated island with no fossil energy and less than half the land to grow enough food to feed themselves, it is highly unlikely that they will ever come up with "another form of energy".

There is no cure for overshoot, not even human knowledge.

Ron P.

Speaking of evolution, here's an interesting report from an interview with Richard Dawkins:

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/20/science/20dawkins.html?_r=1&pagewanted...

I especially like the not wanting to be too dogmatic part.

And just in case you miss this part about his book "The Selfish Gene":

As for overshoot, what overshoot? Evidence please.

As for Julian Simon, I haven't read him. From your representation of two of his views (presumably he has more), he's got one right and one wrong. Not bad, I guess. He's right that the most important resource (I assume he's talking about our species) is knowledge. As for recycling everything, I do believe he ignores the second law of thermodynamics.

As for Japan, it doesn't need to grow energy. It just needs to capture some, either within its borders or through trade, offering the product of its people's skills in return.

So tell me, Mr. Ron P. Darwinian, why didn't the Romans run their chariots on diesel or gasoline? Might it be because they were short a little information? Or maybe you believe that hydrocarbons were only recently delivered to earth by spaceship along with an instruction booklet?

Obviously you have absolutely no idea of what overshoot is. Video: What is Ecological Overshoot?

Or you can read the very best (short article) ever written on the subject. Energy and Human Evolution

Or you could read the very best book ever printed on the subject. Overshoot by William Catton

A short excerpt from the book can be found here: Industrialization: Prelude to Collapse by William Catton

You are a real smart ass aren't you. We have had a lot of such people on this list before but they usually don't last very long unless they tone it down a bit. I am not arguing that we have not used our knowledge to get where we are. Indeed that is the problem.

The population during Roman times was about 230 million or about 1/300th of today's population. And it did not rise very fast until the industrial revolution when it really took off. Fossil fuels powered the industrial revolution as well as the green revolution. That enabled our population to explode. And when fossil fuels disappear, the population will implode. Read the essay linked above, "Energy and Human Evolution" and you will understand why.

Ron P.

+10 LOL

The population estimate for 'Roman times' is interesting, but so what? My question was, why didn't the Romans run their chariots on fossil fuels? After all, the material ingredients were available.

The British agricultural revolution and the British take-off of population began before the industrial revolution; in fact they were both key contributing factors in the process of industrialization, though secondary to the critical role of thinking.

You haven't provided any evidence of overshoot, only some speculative writing. Was China in overshoot when its population was less than half of today's, but millions were starving, in stark contrast to today. (And by the way, did you know that China is the world's largest producer of potatoes, by a long shot, when only a few years ago, it produced next to none.)

You have seen the future (time machine? crystal ball?), and it looks miserable. How sad for you. I guess when you get to purgatory, you can head to Malthus' and Ricardo's pad and join in their chanting: "Any day now, we're all going to hell in a handbasket".

There is an even better example of overshoot.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4734760

A population of mice given unlimited access to food and water and protected from disease and predators goes into a period of exponential growth and then collapses to zero and goes extinct.

A local library was having problems with mice, but it wasn't because they weren't returning borrowed books or disturbing other users with loud debates about the implications of some new invention.

It's true that mice are involved in science, but I honestly don't expect that Mickey or Minnie are about to publish anything in the near future. They've had decades and have yet to produce one page of legible scribbling.

And please, before somebody adds something about some remote island where reindeer had a bad experience, try to remember that Rudolph was a uniquely bright beast. We're just not likely to see his type again among the antlered.

Looks like it's going to be difficult to have a reasoned conversation with you.

I heard the same line, word for word, lo these many decades from a priest when I questioned his dogma.

Nonetheless, I am ready to reason with people who recognize that the act of reasoning separates our species from mice and reindeer. It also helps if my interlocutor(s) appreciate(s) the difference between a tiny isolated population on a tiny isolated island in the Pacific ocean and the modern world characterized by remarkably low, worldwide communication costs and by an immense and ongoing increase in knowledge.

Granted the uptake of knowledge is uneven. Dogmatism explains a lot of this uneveness.

Would the words "limbic" and "reptilian" find a place in such a reasoned conversation?

Because any conversation about human behaviour that doesn't take the unconscious, more primal drivers of that behaviour into account is going to be hopelessly truncated.

So, what's your take on Dawkins?

And what do you mean when you write: "more primal"?

I'd be a little less dogmatic than Dawkins. I would agree that we can probably overcome our genetic impulses some of the time with our reasoning capacity.

Unfortunately, for most human decisions the reptilian and limbic systems (which are evolutionarily older and therefore more primal parts of the brain than the neocortex) play a very heavy role in our decision-making due to their connections to our emotions. This gives the decisions and actions they influence a much stronger sense of immediacy and urgency than those arrived at through pure neocortical reasoning. The influences of the limbic and reptilian systems tend to be below the threshold of rational awareness. As a result these influences are notoriously hard to detect and control, though one can learn to do it to some degree with training and practice.

What this means is that for most people decisions related to survival, reproduction, status and social acceptance, the exercise of or submission to power - and all the activities that impinge on such issues - are not terribly rational, and in fact tend to be be irrational and emotional. Most such decisions are merely dressed up with post-hoc rationalizations when they appear, already fully formed, in our cortical consciousness.

Man is not nearly so rational an animal as his conceits would have it. We can be better described as rationalizing animals.

Clear enough?

Ya think?!

We ain't gonna see the likes of Rudolf the red nosed reindeer with his shinny nose anytime soon...

Well I guess one might call that a reasonable assumption!

Sigh.

So what is the mechanism by which women in many places (Japan, UK, Canada, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Spain, Austria, Greece, Russia, Ukraine, the EU) are deciding to have children below replacement rates (2 children per woman)?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_and_territories_by_fertil...

Conscious choice.

A small quibble: two children per woman is below the replacement rate, only slightly given declining mortality among the young, but still below.

How is their conscious choice different than the unconscious choice of the mice to not reproduce?

Wiedemann would probably say that for the Romans the less expensive exploitable energy source was human slaves (his Greek and Roman Slavery book is very good).

Consider that a quick snapshot of Caesar's Gallic campaign brought 1 million slaves when Rome had a population of 1 million, never mind the Germanic and African

slave from Gaius Marius or Cornelius Sulla prior. War for the Romans was a profit center.

You are correct, I missed that. I knew the "Edos" were an indigenous tribe in Nigeria but was unaware that it was also a period in Japanese history. Japanese history is not my strong suit. Sorry about that.

However they proved that they did not have what it took to be sustainable by becoming the most unsustainable nation on earth. If they had truly been sustainable that would not have happened. You must realize that sustainable means to live sustainable, that is too keep their population from overshoot. Edo Japan failed miserable in that respect. They were never sustainable because thy could not control their population growth.

Ron P.

I'm not great at Japanese history either (but I'm not bad at google '-)

Actually, it seems that Japanese population was remarkably stable throughout most of the Edo (or Tokugawa) era, staying at around 30 million from 1700 to about 1850, then edging up a few million toward the end of that century.

Yes, the Japanese population eventually exploded when they could no longer resist the 'gunboat diplomacy' of the west. But the question is, are there examples of systems or regimes that consciously limited their technology and their population in order to avoid overshoot, and it looks like this period of Japanese history might be one worth looking at more closely.

Don't expect a paradise--there were rigid caste systems and severe punishments...

We're not looking for paradise here, just a system that doesn't explode.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Japan_before_Meiji_Restoration

However they proved that they did not have what it took to be sustainable by becoming the most unsustainable nation on earth. If they had truly been sustainable that would not have happened.

The use of 'they' needs definition. If the 'They' would be the leadership and population of Edo - not 'they' being Japanese - then you, Darwininan is wrong (again) on a matter of history.

Matthew Calbraith Perry went to Edo Japan with guns and the threat of force and ended the Edo period.

The leadership of Japan decided on a different path due to the threat of force.

But for Darwininan to be correct, a people are defined by ONLY their location. I'll leave it up to the readers to decide if people are defined by their location only.

Edo Japan was fairly close to sustainable.

Surely you jest.

You are either ignorant or wanting to make the next statement.

Japan is perhaps the most unsustainable nation in the world.

As is my tradition:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edo_period

You now have a starting point on removing your ignorance.

(I was going to use One Straw Revolution http:www.arvindguptatoys.com/arvindgupta//onestraw.pdf as a peg to hang a comment about taking material from the Sea to the land as part of closing of a loop / adding to the food supply such that comments about arable land when one can obtain material from the sea are not the best comparison, but alas One Straw was not the source my memory had it to be.)

Not sure about that. The human species is in massive overshoot and the results of the modelling may well be that fewer humans can live sustainably at lower standards in a damaged and resource depleted world. I do not know how many humans and to what degree technology will survive. Certainly some humans and some technology will survive, but what is almost certain is that this world will be much less complex.

One aspect of the modelling that appears to be missing is the impact of the capital markets and what form these will take over time. during the contraction I suspect they may well be highly dysfunctional and one aspect of the great contraction (already present) will be virtually non existent credit availability.

This leads inevitably to the consideration of whether modelling the world after the great contraction is worthwhile. Maybe our most immediate need is to understand the great contraction and how the effects of that can be mitigated.

Nevertheless this is a fascinating project and I wish I was smart and well educated enough to be able to apply. Even though I have a Master of Sustainability Science degree I feel woefully inadequate against the task at hand.

I think there are many sustainable solutions. The trouble is that a sustainable solution reveals something about our true nature as living things and most of the obvious sustainable solutions give a picture of us that we don't much like to see. We would like to find a sustainable solution that is more harmonious, less brutish and nasty. That doesn't require changing human nature, I think, but building social structures that limit the consequences of the worser aspects of human nature.

Yes exactly, the solutions that are harmonious and sustainable in the long term don't fair well against unsustainable, short term and brutish "solutions".

Gail, I think you confuse the issue of a system removed from its original state with one that is in equilibrium. A few thousand hunter gatherers became part of an evolving system. Theoretically at least it should be possible to stabalise the Earth Ecosystem in some new state but I very much doubt this will be possible with 7 billion humans on the planet.

Of course no ecosystem is ever in a state of equilibrium but rather a state of dynamic equilibrium so the architects of the model may be able to choose how much evolution is permitted per unit time.

It sounds like you are too busy worrying about the minutiae of modeling. What is the point of modeling silly things that can never be? My issue with Gail's writing is she dreams of a world where some authority will regulate these resources. Both goals are totally divorced from the reality of human behavior.

Peak oil is the only hope for sustainability. Only a hard limit that declines over time will scale back human activity. As long as resources can be found, the world population will double and redouble until we become the yeast culture in the test tube. Call me a cheer leader for peak oil ;)

"Peak oil is the only hope for sustainability. Only a hard limit that declines over time will scale back human activity."

What then. As in the past, a new drama will unfold. Perhaps we'll call it "Desperately Seeking Substitutes" :-/

Yes, the great project now is not how to expand our capabilities, but how to limit them, especially the capabilities to consume the world.

Let us assume the perfect model is constructed. What is the result?

1) The solution is presented - we must reduce the global population to less than 1 billion people.

2) The solution, while very simple, is deemed impossible to implement. Case closed, model and report are ignored. Authors are labeled as crazy tree-huggers or agents against humanity.

Humanity needs to go through The Great Lesson - a real-world crisis that proves to the masses we cannot have exponential growth in a finite system in perpetuity.

When all the dust settles and the rebuilding begins, will we have learned our lesson? Will we be able to construct and manage sustainable communities and protect them from outsiders that didn't learn the lesson?

The problem with technology is that complexity requires massive energy gaps and plentiful resources. Hopefully, we will have a few areas that can keep our collective knowledge and keep moving it forward.

Until then, It seems the best play is the short-sell and hedge bet. Enjoy it while it lasts, this just may be the finest hour of human civilization.

Yes, a crisis is doubtless necessary, but please note that there are no shortage of those in the world. What you need to have on hand when a crisis occurs is a plan for how to proceed once the crisis makes many question the dominant paradigm. This is how the Chicago school implemented their (ultimately disastrous) schemes all over the world (See Naomi Klein's "Shock Doctrine"). If this approach can work for ill, perhaps it can also work for less nefarious ends.

Agreed Tt. You may model as much as you like, if human population doesn't decline significantly, every modeled future will suck. It's like mopping with all taps running.

Concerning Gail's comment: "man has such an unfair

advantage" ...

Reminds me of a Scientific American article from perhaps

45 years ago. It compared abundance of mammal species

based on a typical specimen's weight. A summary graph

was on log-log paper with the X-axis being the log of

a typical specimen's weight and the Y-axis being the

log of the abundance of the species. Most species were

on a straight line from top left to bottom right. In

the lower right corner was Blue Whale (200 tons); if

memory serves the upper left corner was some species

of field mouse (< 1 oz.).

The exact extremes aren't important. What is important

is that one species wouldn't fit on the graph: Homo

sapiens which based on the typical specimen's weight

was at that time 30,000 times too abundant to fit on

the line.

Since 1965 human population has gone from 3.3 Billion

to today's 6.8 Billion and many other species have

declined. So we're probably 60,000 times too abundant

to fit on the ~45 year old line today.

Indeed "man has such an unfair advantage ..." and

we're using that advantage to terraform the planet

so that the only species left will be plants and

animals we eat and plants and animals we feed to

animals we eat which of course is an extreme that

can't be reached.

If the global human population were decreased by

99.998% to ~150K the planet would get a rest.

However civilization would suffer. As just one

example it would be difficult to maintain the current

let alone develop the next intercontinental jet.

How about 50 million people?

"Don't accept the chauvinistic tradition that labels our era the age of mammals. This is the age of arthropods. They outnumber us by any criterion--by species, by individuals, by prospects for evolutionary continuation. Some 80 percent of all named animal species are arthropods, the vast majority insects."

Stephen Jay Gould-- Wonderful Life p 102

"There's plenty of hope, an infinite amount of hope, but not for us." --Franz Kafka

MD3,

For a long time I speculated that Homo sapiens outweigh

any other single species including termites or any other

specific Arthropod. I was surprised to learn that for a

couple of months in the Antarctic Spring krill (an

Arthropod of the Subphylum Crustacean) outweigh Homo

sapiens by a wide margin. However there are ~85 known

species of krill so it might not be comparing apples with

apples.

You quote Gould (for whom I had a lot of respect): "They

outnumber us by any criterion--by species, by individuals,

by prospects for evolutionary continuation." That quote

doesn't include the criterion of "total weight of a

specific species."

By reading lots of articles and comments I conclude that

chauvinistic or not from the perspective of most TOD

posters and readers the ecological footprint of Homo

sapiens is of far more concern than that of all Arthropods

combined.

Ruddiman's Early Anthropocene Hypothesis

http://westinstenv.org/palbot/2010/12/08/the-anthropogenic-greenhouse-er...

This is why nuclear power is so important.

Desperate, starving people will destroy everything and eat anything (see Haiti, or any of a dozen overgrazed-to-dustbowl countries in Africa). Nuclear power does not compete with ecosystems for anything of great significance; uranium and thorium in particular are useless to everything on the planet that we know of, except us. Taking the energy demands off the ecosystems frees more for nature (even before the effects of effluents are considered).

It may even be possible to turn nuclear energy into food. Archaea can make methane from CO2 and electrons (a process which Electrochaea is trying to commercialize). Methane can form the basis of a food web which needs no sunlight (there are similar food webs around volcanic vents). No sunlight required means no surface fields required, and so forth.

I know that some "green" types think of humans as Morlocks, but we really do have the option of re-writing the story without Eloi.

That is rather interesting. If it came about I doubt it would be good for the planets life in the long run. We would simply continue to expand the population and impact, and the ultimate level of damage would be greater still. We would simply runaway with the noyion that since we are separate from nature, that we don't need it. So I doubt you'll attract any fans here.

The societies (First world) capable of doing these things have already reached ZPG (even the USA is only growing as a result of immigration). All that's required is to refuse to share with nations which don't limit their numbers and educate their populations.

I don't think you appreciate the difference it would make if people didn't have to dominate or destroy nature just to avoid starvation. Desperate people do not have the luxury to care what else is lost. Wealthy, secure people do.

There is no reason to believe that zero population growth will persist anywhere perpetually except in the case of extinction. Population collapse follows a bell curve. Near the peak there is approximately zero change in population which can be deceptive for those who reject overshoot. Yeast in a Petri dish enter population collapse from either resource depletion or pollution depending on the amount of food they are given.

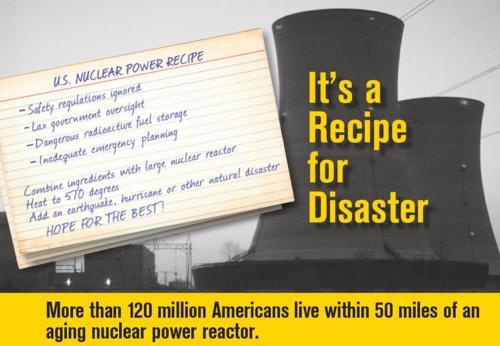

Although Japan had an earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster all at once, you do not understand the looming disaster posed by nuclear power. Even when the nuclear power industry externalizes its risks upon its victims, the clue sails right on by you.

It's been "looming" for decades, but for some reason it never seems to get here (save for Chernobyl). The death toll from the meltdowns at Fukushima stands at zero. There were what, 3 minor injuries from beta burns? The Japanese people are getting annoyed with the anti-nuclear paranoia driving all the news coverage; there are lots of people who could use help and attention, but they're never mentioned and get no mind-share because of the anti-nuclear agenda of the MSM.

The biggest irony is that the Fukushima Dai'ichi plants were among the oldest and least-refined designs running anywhere in the world. Newer plants of similar design rode out the quake and tsunami just fine, and a healthy program of nuclear development and expansion would have replaced those outdated plants already. Modern designs don't need electric power to prevent fuel damage. The lack of this healthy program is largely due to the efforts of anti-nuclear activists, hyping non-existent "looming disasters".

I love the smell of irony in the morning.

NB: For those who didn't get the memo, we did NOT almost lose Detroit. This 1976 document debunks the hype around Fermi I.

The death toll from the meltdowns at Fukushima stands at zero.

Citation please.

There were what, 3 minor injuries from beta burns?

Again, provide citations.

The Japanese people are getting annoyed with the anti-nuclear paranoia driving all the news coverage

Now you are speaking for 'the people'?

I'm REALLY looking forward to you showing your data/sources on this claim.

My comprehensive rebuttal, WITH REFERENCES, was deleted from this thread.

I protest this unconscionable censorship on the part of TOD's administration and demand the return of my work to me. Research is not free. It takes time and effort. For all intents and purposes, I have just been robbed of it.

I also protest that the baseless trollish charges made in the parent ARE ALLOWED TO STAND while the rebuttal was censored without a trace. This bias is why nothing about this issue gets settled; the science has been here for decades, but only the anti-nuclear side is allowed to speak.

Repost w. edits (thanks, Kate)

It's hypocritical of you to demand this given that you never give any, but for the rest of the world I'll summarize what everyone ought to know already.

The only nuclear-related injuries listed here (last updated 9/20/2011) are those detailed here, claiming 3 with beta burns due to lack of protective equipment (walking through contaminated water without waterproof boots!), only 2 requiring hospitalization. All other injuries and the handful of fatalities (3?) were unrelated to radiation.

Unlike you, I let the Japanese speak for themselves. I just pay attention to them instead of ignoring everything that doesn't fit a "nuclear problems are the ONLY disaster" narrative.

We are likely entering/have started to enter a period of climatic, economic, political and social chaos.

In this period, every nuclear plant is a potential Fukushima or worse.

Even if we somehow ride out the current set of storms comparatively unruffled, history tells us that eventually every area experiences chaos. When that time eventually comes to each nuclear plant, they will blow, with more or less devastating consequences for the region and the planet.

Nuclear proponents are often quite knowledgeable and excited about technology and nuclear physics. But they seem to be stunningly ignorant or naive about history and the consequences that the inevitable chaos that it brings will have on their tidy little plans.

Which will be much worse in areas where there is no reliable electric power.

I'd say you have it backwards: the fear of a Fukushima will accelerate and exacerbate the chaos.

If you have such a concern, it would be sufficient to provide enough dry-cask storage to store all irradiated fuel at each site and substantial amounts of fuel for the generators. If chaos makes it impossible to continue running a plant, the generators will allow it to be shut down and the fuel loaded into dry casks for indefinite storage. This avoids unnecessary blackouts leading to chaos on their own.

A PWR operating at 30% of full power could go roughly 5 years without refuelling. That's enough time for a lot of chaotic things to be resolved. Other technologies could be far more robust; an Integral Fast Reactor could be supplied with enough raw breeding material for its complete lifespan at the time of construction. Even if it needed other consumables or parts every 10 years or so, that's a long time to be able to wait compared to a gas-fired turbine. A nuclear economy would be almost immune to disruptions in fuel supplies, from politics, chaos or anything else.

If you have such a concern, it would be sufficient to provide enough dry-cask storage to store all irradiated fuel at each site and substantial amounts of fuel for the generators. If chaos makes it impossible to continue running a plant, the generators will allow it to be shut down and the fuel loaded into dry casks for indefinite storage. This avoids unnecessary blackouts leading to chaos on their own.

I have such a concern. The reported cost of a single dry-cask storage unit is over $1M currently, with the cost guaranteed to go up as we head further into a situation with high inflation and no surplus energy for such shenanigans. The dry casks are supposed to last 100 years, but have a history of defective welds that spring leaks quickly. The cost of dry cask storage is so great that Nukes have put off dry cask storage, opting instead to double stack, rack, and rerack the fuel in spent fuel pools (SFP) that, in Fukushima's case, have now spread spent fuel and Mox fuel loaded with plutonium, strontium, and other relatively permanent isotopes across the Japanese landscape. So the cost of offloading into casks from SFP is already prohibitive and not something that private nuke corps will do without government assumption of cost.

Dry-casking spent fuel is not a decision to be made in an emergency; the fuel of a scrammed nuke has to be cooled for at least a year before it can be moved to a SFP. Then the fuel must be cooled in the SFP for another 4 or 5 years before it is cool enough to be put in dry casks. During that 5 years, cooling must be maintained with no interruptions of more than 100 minutes, or the fuel will boil dry and burn up, permanently rendering the countryside within 50-100 miles unlivable, and making a much larger swath of the US dangerous due to lower levels of radiation. So all of that fuel in SFP in the US (many times the amount at Fukushima) is just a bunch of sitting dirty bombs of our own terrorist behavior, waiting for one 100 minute broad breach in electricity delivery as complexity starts to deconstruct.

And I will stand by my original statement that in the end, the Japanese will throw a sheet over the 6 or 8 China Syndromes that is Fukushima and walk away from the middle part of Japan as food chain and waste contamination continue to concentrate, making the central part of Japan unlivable. The corium is now 25 feet down into the groundwater. Incinerate wastes and sewage, and isotopes disperse quickly. Can the fish, give it away to poorer neighbors as a gesture of good will, and the isotopes disperse slower. Wait long enough, and the fish in the Pacific food chain are inedible. Any "fixes" just move the isotopes around and spread things further. The problem with isotopes is that they last too long (25,000 years) and cannot be mediated.

100 minutes is all it would take to get the party started in the US. We're getting lots of warnings, too, that running 40 year old nuke plants that are past their design limits is not a good idea. The nuke plants are debt men walking, and they know it. The good news is that leukemia takes 5 years and the other cancers take 10+, so the corporations responsible can say, I'll Be Gone, You'll Be Gone, just like the financiers on Wall Street. Use up all the oil, decimate the food chain, and leave Mad Max for our kids. Thanks, EP.

A quick search turned up a figure of $20-30 million for storage to serve a 2-reactor plant. That's a fraction of 1% of the price of a new plant, perhaps $1.5-$2 billion for the entire USA. It should have been done as part of the stimulus.

No citation, and an apparent self-contradiction: how does a dry cask spring leaks?

Of course. Government has failed to take the fuel as it is contracted to do and is collecting a 1 mil/kWh fee for doing. Would you go to your shareholders and say you want to spend $15 million per reactor for dry casks, or would you re-rack? Let's take the Yucca Mountain fund and spent it on dry casks.

It's already been done at every decommissioned plant in the USA, and a few which have overflowed their SFP capacity.

Fuel has to be moved to the SFP before new fuel can be inserted. This takes days, not a year; the fastest refuelling intervals in the USA are a mere 15 days.

Active cooling is required for a while if the coolant is water at atmospheric pressure, but placing the fuel in a pressurized container which can hold a non-corrosive coolant (CO2 under pressure might do) would allow it to self-cool at a slightly higher but safe temperature. I've worked in a shop which could build such vessels, no problem.

Cs-137: 30.17 years. Sr-90: 28.8 years. I-131: 8.02 days. Those are the worst of them, because they wind up in the metabolism.

I had to quote this because it's so over-the-top. Yet some people take it at face value... I'm just amazed. The level of ignorant fear never ceases to surprise me.

Cs-137: 30.17 years. Sr-90: 28.8 years. I-131: 8.02 days.

Stating one half-life for how long the isotope "lasts" is also over-the-top when we know it remains extremely dangerous for many half-lives. I know you're not this ignorant. If this was true, much of the contents of SFPs around the US would be totally harmless by now.

The claim "25,000 years" is approximately the half-life of Pu-239. I was comparing like to like.

Courtesy of All Things Nuclear.

Weak troll. Your propagandists can barely get one fact right (reactor temperature).

LOL. Rebranding efforts are going to have to double. Lots more at Stephanie's link.

http://www.stephaniemcmillan.org/codegreen/

More silly propaganda, sans rational analysis.

In reality, natural gas kills far more people than nuclear power, but its hazards are ignored by the MSM. Maybe you'd like to explain this very selective blind spot... or maybe not.

Not sure about that. Some weeks after the Tsunami infant mortality rates spiked on the US West coast! I suspect it will be almost impossible to attribute the spike to the disaster, nevertheless the mere fact that there is a chance it can be attributable should give one pause for thought.

The contamination of the sea has yet to run its course in terms of human damage. We shall have to wait and see what happens in the months and years ahead, while on land various isotopes of Caesium and other nasties are turning up in vehicle and airconditioning filters. This means almost certainly that these particles will also have lodged themselves in peoples lungs. Will cancers diagnosed in 10, 15 or 20 years be attributed to Fukushima? I doubt it. One only has to look at the cancer records around Chernobyl and the Tuamotus (Mururoa) to get a feel that Fukushima is a very long way from being played out. BTW the total radiation released to the environment from Fukushima exceeds Chernobyl by a wide margin. And the distaster continues, even though it is no longer front page news. At least 3 cores melted down right through all the containment vessels and I have not heard what is happening now. The Japanese are excellent at creating maximum opacity.

We are a very long way from having viable disposal strategies for nuclear waste. Only a very small proportion of all the nuclear waste ever created has been permanently stored. Until we do learn to deal "for ever" with the waste, nuclear energy is a non-starter in my opinion and I oppose it when ever possible. Remember, the oldest human constructions in existence are some 10,000 years old. And they are not in great shape. It seems somewhat arrogant that we think we can can build something that is expected to last for 250,000 years, especially something that has the durability and complexity needed to safely store nuclear waste for that long.

Finally, I applaud the decisions of Germany and Switzerland to phase out nuclear power. But I want to see things go a whole lot further. Firstly all Mark 1 Boiling Water Reactors should be closed down immediately. They have inherent design flaws that are not rectifiable. Thereafter all countries need to enter into a public debate about whether they should continue with nuclear power. What democracies do about totalitarian states like China, Iran and Russia I have no idea. Chenobyl taught us that radiation is no respecter of international borders. Meadows in Wales still cannot be grazed some 25 years after the disaster. The fact that all of this is happening during Peak Oil and when we should be cutting back on coal use is a disaster.

Personally I would prefer it that when the lights go out that it is actually dark, rather than being lit by an unearthly radiation glow!

Citation, please. Also please provide a mechanism for barely-detectable traces of radiation to have a much greater effect than the doses received in Japan. Are you suggesting that Fukushima emissions are like homeopathic medicines, more powerful the more they're diluted?

You do realize that homeopathy is bunk, don't you?

I doubt it too. Aside from thyroid tumors nearby, there was no great spike in cancers from Chernobyl either. Certainly not in Europe.

Whereas the real authorities say "The total radioactive release from Fukushima is currently estimated at about 5.5% of Chernobyl". Cs-137 emissions at Fukushma are about 1/5 of Chernobyl.

You have NO respect for the truth, sir. Shame on you.

That's a gross exaggeration of the most sensational headlines I could find in a search.

For shame, sir. For shame!

The Egyptian pyramids are upwards of 3000 years old. The Coliseum is ~2000 years old. The waste products from e.g. LFTR become less radioactive than uranium ore within about 500 years.

Paranoia stokes political power, but it doesn't solve real problems.

I don't. They're crazy, and inevitably going to violate their obligations under climate-change treaties. Nuclear energy is the only source available in sufficient supply soon enough to keep us from pushing the earth into an Anthropocene Thermal Maximum to rival or exceed the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum.

Infant Mortility: http://english.aljazeera.net/indepth/features/2011/06/201161664828302638...

Thyroid Cancers in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs303/en/index.html

Radiation Releases: http://www.zerohedge.com/article/run-rated-fukushina-radiation-release-p...

Incidentally I do not trust TEPCO of the Japanese government. They have been shown to be economical with the truth too many times. In addition I am not sure anyone can ever know how much radiation was picked up by seawater during the efforts to cool the reactors in the days and weeks following the incident. Perhaps releases into the sea are not as bad as releases into the air as with Chernobyl. I guess we will have to see.

Melt throughs: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/japan/8565020/Nuclear-fue...

Waste: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High-level_radioactive_waste_management

Not only is fission inherently dangerous, but it is not financially viable (ie it cannot either be insured or financed other than by governement). I would also like to understand what its EROI is. The last estimate I read was 5. If so that is too low for all the trouble.

Hopefully I have demonstrated that I do have some evidence to back up my opinion. Maybe not the sort of evidence that stacks up in peer reviewed science or a court room, but that is the overwhelming impression I have from reading a wide a array of sources on this issue. So Mr/Ms Engineer-Poet I would appreciate you desisting from all the ad-hominem attacks in this forum. They do not belong here.

Clearly you are a nuclear power supporter. Fair enough, but that doesn't mean Germany and Switzerland have got it wrong, or that my opinion isn't valid.

Oh, goddess! A "news" item from al-Jazeera, which leads with a quote from Arne Gundersen! You can't get much more propagandistic than that. Nor can you get any more self-interested. al-Jazeera is headquartered in Doha, Qatar. One of Qatar's major exports is LNG, which is one of the products Japan will need to replace power from the closed reactors. Do you think a Qatari news source is going to do anything but hype the dangers of nuclear power in Japan? Follow the money.

The "35%" increase was in a total death count of 125 (presumably from a long-term average of 80-odd). This is supposed to be "statistically significant", but a 95% confidence interval will be exceeded by random chance 5% of the time. For a 10-week average, we'd expect that to happen around once every 4 years.

You also ignored the dose-response issue after I put it front and center. The levels which reached the USA were "hundreds of thousands to millions of times below levels of concern". Looks like pure bunk to me.

That's never been questioned. Chernobyl released lots of I-131, and people did not receive treatment to prevent uptake. But that sort of disaster requires mismanagement of a graphite-moderated, water-cooled reactor like the RMBK, and nobody in their right mind will build another one.

Dated March 23, and debunked by later and more authoritative sources that I already gave you.

You seem to be ignoring Finland.

The "problem" isotopes of I-129, Tc-99 and Np-237 really aren't. They can be chemically separated and, because of their low activity and heat output, isolated very easily (especially compared to natural materials of similar toxicity, such as arsenic). Np-237 in particular is usable as nuclear fuel in fast-spectrum reactors, or bred to Pu-238 for use in heat sources such as for RTGs. Pu-238 has a half-life of 89 years and decays to U-234 (both of which fission in a fast neutron spectrum).

France and China seem to have good luck with the government model. Since the advent of the NRC, the USA has had government in the role of roadblock and cost center without any identifiable improvements in safety. TMI Unit 2's meltdown was partially due to a failed instrument mandated by the NRC, but the pre-NRC Unit 1 ran and continues to operate to this day; it received a license extension through 2034.

A nuclear plant uses a fraction of the steel and concrete of a wind farm of the same nameplate wattage, and has a much greater capacity factor. Wind farms have calculated EROEI of around 20-25, so nuclear has to be as good or better. The only way it can be worse is if "regulation" and interest costs are counted as energy costs, which is bad accounting.

To make your case you need evidence which backs your argument unequivocally. I don't think you've managed that.

As for Germany, Angela Merkel is a highly accomplished physicist, with several books to her name such as Merkel, Angela; Lutz Zülicke (1987). "Nonempirical parameter estimate for the statistical adiabatic theory of unimolecular fragmentation carbon-hydrogen bond breaking in methyl". Molecular Physics 60 (6): 1379–1393. Bibcode 1987MolPh..60.1379M. doi:10.1080/00268978700100901.

I doubt she entered into Germany's no nuke policy with her eyes closed.

Angela Merkel went into the last election proposing to reverse the Green's policy of nuclear shutdown. And, for a while, she and her party actually did so.

Which position do you think was based on facts, and which on political considerations?

Since the 1970's, on average there has been 1 core meltdown per decade.

There were two bodies found in the rubble on March 30, 2011, and decontaminated. They were not reported as missing until March 16, 2011. There were reports that they died from the tsunami (March 11) or during the explosion of reactor 3 (March 13). After the explosion, TEPCO stated:

TEPCO has released so many contradictory statements and consistently downplayed the seriousness of the disaster, that it is not possible to make positive assertions about the death toll to date. Because radiation exposure can kill people decades after the exposure, there will be no final tabulation until the nuclear disaster at Fukushima is a distant memory.

Death toll is a pathetic metric for a nuclear disaster. You ignore all the people who have been removed from their homes and jobs. You omit sickness and injuries caused by radiation exposure and explosions. The contamination of land for longer than a human lifetime and the loss of farms, fish and livestock are a crushing burden for victims who you ignore. Using Chernobyl as an indicator, people and products from Fukushima will be shunned. As long as such burdens fall upon others, nameless, faceless, unknown souls, I am certain you will be content with your advantage gained by externalizing the costs and consequences upon them. Even while a disaster is ongoing, you ignore it, trivialize it.

You have it backwards. Those liberal arts majors whose paychecks are paid in part by the nuclear industry spout the propaganda of their masters. Usually that means they do not report nuclear events, and when they do, they are massively slanted toward no problem, no risk and no danger so the viewer/reader should move along and direct his attention to something else.

There are lots of these defective General Electric Mark I reactors still in operation. Fukushime Daiichi was the closet nuclear power plant to the epicenter. Distance matters with earthquakes and tsunamis. A healthy program of nuclear development and expansion does not exist because it cuts into the profits demanded by the bean counters. Those anti-nuclear activists warned TEPCO that their sea wall was too low while TEPCO insisted it was plenty high to handle the worst case scenario. Those anti-nuclear activists did not have anything to do with constructing reactor buildings too close together or locating backup diesel generators in places that could be flooded. Nor did they have anything to do with workers neglecting to refill the fuel tank of a fire truck pumping cooling water into reactor 1. Despite its imperfections continuing unabated, I sense an idealistic belief that technology can be perfected.

And we've wiped out life on Earth? Everyone's gotten cancer? We've awakened Godzilla and he's stomping Tokyo flat?

None of those things, you say? It's so subtle that nobody noticed?

I suspect that we've released less radioactivity into the environment from nuclear energy, meltdowns included, than coal power due to the tramp U+Th in coal.

TEPCO was dealing with a crisis situation. The people briefing the press had a Catch-22: if they vetted their information thoroughly they would be accused of stonewalling, and if they did not have their facts absolutely verified before talking to the press they would later be accused of lying. The rules you insist on amount to "heads I win, tails TEPCO loses".

You state a claim contrary to your reference, which begins "The bodies of two workers killed by the tsunami"...

I copied your link so readers can see that it points to a report from March 14. You couldn't be bothered to check later reports to see if the 7 "missing" were actually harmed, missed in the headcount after the fact, or not actually at the site at the time of the event. I did check, and found this timeline which says 4 workers and 7 soldiers injured, ZERO dead.

Do you think "radiation" is an unknown quantity? Do you believe we don't have data on the effects of radiation exposure going on 7 decades old, and actuarial data on the long-term effects?

The radiation from the bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki had no detectable genetic or other effects on survivors receiving low doses. No members of the public received high doses from either TMI or the Fukushima, so this "looming disaster" is a shadow cast by fears in the darkness of ignorance. Turn on the light and it disappears.

Pure, unadulterated falsehood. The science agencies and Japanese people had plenty to say about all sorts of things, but the MSM only wanted to talk about nuclear problems. (This video was linked in my censored rebuttal to "eric blair" above, which proves conclusively that the Japanese do not have the all-meltdown all the time paranoia that he does.)

If only. In the real world, the MSM takes a minor industrial accident and blows it up into an international news item because it occurred at a French nuclear waste handling plant.

Wrong again. The plant at Onagawa (on the mainland side of the Oshika peninsula at the top of this image [source]) was considerably closer to the quake than Dai'ichi. The Onagawa plant served as a refugee center after the quake and tsunami. (The 3 reactors at Onagawa are all from Toshiba. It appears that a lot changed between 1969 and 1984, doesn't it?)

Empty accusation. GE has had designs out there for decades, but has been blocked by NRC red tape and political hatchet jobs in the US Congress (see the tale of the Integral Fast Reactor, killed by Hazel O'Leary and John Kerry). The only winners are the coal and gas industries.

True. But the goal of the anti-nuclear activists is not to fix the vulnerabilities of nuclear power. It is to kill it, regardless of what they have to do or say or what replaces it.

The main error with the "just go nuclear" plan is that the problem is not just with energy. The problem includes many other resources (arable land, fresh water, clean air, toxic-free zones, radioactive-free zones, threats from man-made substances, ocean fisheries, depleting mineral deposits, etc.). How can this not be obvious to people that understand the Peak Oil premise?

by the way, uranium is a non-renewable resource that will peak soon as well. Can the failing global economy even afford these massive monuments of human ingenuity with their ever-increasing costs, both financially and environmentally? Of course, the answer is no. Even today, only governments can afford these systems because they can spread out all of the costs (security, fuel enrichment, unlimited liability, decommissioning, radioactive waste storage, Fukushima-like disaster responses, etc.) to all of their citizens, even if these citizens have no idea what is going on.

Nuclear is dead, may it rest in peace.

This assumes that we don't make use of technology that has been known about for fifty years and trialled over thirty years ago. That is possible; but it's a choice, not a certainty.

With enough energy we can desalinate water and remove toxins from it. With enough energy we can clean up toxic zones and recycle minerals cleanly. With enough energy in the right places we can reverse erosion and increase arable land.

We're going to have to live with radioactivity, just as we now live with radioactivity (yes), AND arsenic, sulfate aerosols, ozone, and toxic nitrogen oxides from burning fossil fuels. It's the lesser of two evils, the other of which is killing life in the oceans.

Nuclear power is finite, but it could keep 10 billion people in European levels of comfort for several centuries. That's enough time to reduce the population to sustainable levels in a non-catastrophic way, if we choose to.

All is choice.

Radioactive-free zone?! Where can you find one of those? I doubt there's been such a place anywhere in the universe since the first supernovae went boom and made elements heavier than lithium (and filled zones far beyond their remnant nebulae with high-energy cosmic rays). Earth is full of uranium+thorium and their daughter isotopes, potassium-40, carbon-14 and other all-natural stuff. A little more isn't likely to be harmful; the "linear no-threshold" model is known to fail to describe observations at low, chronic levels of exposure. Areas with high natural levels of radioactivity do not have the disease/mortality statistics LNT predicts.

Nuclear power helps a lot with the other parts. Cleaning up air, eliminating toxics from fossil fuels, desalinating water (and avoiding contamination of natural supplies from e.g. fraccing), stopping ocean acidification, all benefit from nuclear energy. With cheap energy, depleting resources are easier to recycle. The list goes on.

It's you who haven't thought about it enough.

Of course I am not talking about background radiation but man-made radioactive waste that can kill people for thousands of years and make places like Chernobyl and Fukushima less desirable for family picnics.

Regarding what the poster above said about using our other "sustainable" nuclear fuels, I feel a thorium debate coming.

How about we wait until there is a great, fully commercialized thorium or breeder power plant running by a private company profitably before we get into deep discussions on the topic.

Maybe man-made (have to put this in here because the above poster will start talking about the sun being a fusion reactor) nuclear power will save humanity and Earth's ecosystem... But I doubt it.

Too bad we don't have another earth-like planet close enough to us to try out a few different scenarios.

The one thing I am sure about is there will be people able to figure out how to live very well, indeed, during the long crisis. There just won't be as many of them that we have today.

The stuff at Fukushima is IIRC primarily cesium, which binds strongly to materials like concrete and other minerals. It's not going to make the area undesirable for picnics. Even at Chernobyl, the top soil layers are being depleted in the radioactives as they wash towards the subsoil. Increasingly, to be exposed to significant radiation would require literally digging it up.

The other issue at Fukushima is strontium, which is taken up like calcium. It may make it unrealistic to grow food crops in the contaminated zone for a couple of half-lives, or until it's flushed out by something like lime treatment or depleted by growing several crops of calcium-intensive plants and throwing them away (bio-remediation).

I'd be happy to. Get the NRC out of the way and let Flibe Energy do its thing. But we know that's not going to happen, so I refuse to accept your conditions for having a discussion.

The question is whether people like you will even allow people like me to try to prove you wrong.

"Increasingly, to be exposed to significant radiation would require literally digging it up"

Luckily, humans never have dug and never will dig into the ground.

/sarc

Oh, the irony. Here we are talking about sustainability and you're proposing the only energy source, which, by its very nature (that of destroying matter), can never be sustainable.

I can't believe this. Please look up the Integral Fast Reactor, or thermal breeder reactors using thorium (possible in several different ways) for a start.