Jevons' coal question: Why the UK Coal Peak wasn't as bad as expected

Posted by Rembrandt on August 15, 2011 - 10:45am

In his book The Coal Question from 1865, William Stanley Jevons examined for how long the United Kingdom could continue to fuel its economy based on cheap supplies of coal. At the time the UK consumed about 93 million tons of coal, providing nearly all of its energy supply. His estimate was that within a maximum of a hundred years, or perhaps even within one or two generations, production would be in retreat due to an increase in the cost of mining which would, in Jevons' words, "Injure the commercial and manufacturing supremacy of England."

In this post I’ll look back at history to show that Jevons correctly foresaw the fate of the British coal industry. In Britain a peak in production occurred around 1913 caused by increasing coal mining costs, lack of technological innovation, rising competition from abroad, a number of political decisions disadvantaging coal as a fuel source, declining profits, and a slump in British economic growth coinciding with World War I. Although geology had an important role to play in determining the cost of coal, it was not the overarching factor that led to the decline in British coal production. Fortunately for Britain, Jevons was too pessimistic about the economic consequences. He did not foresee both the adaptation of the British economy in reaching higher overall efficiency in a high energy price environment, and the eventual large scale introduction of petroleum.

Jevons' analysis on British coal supplies

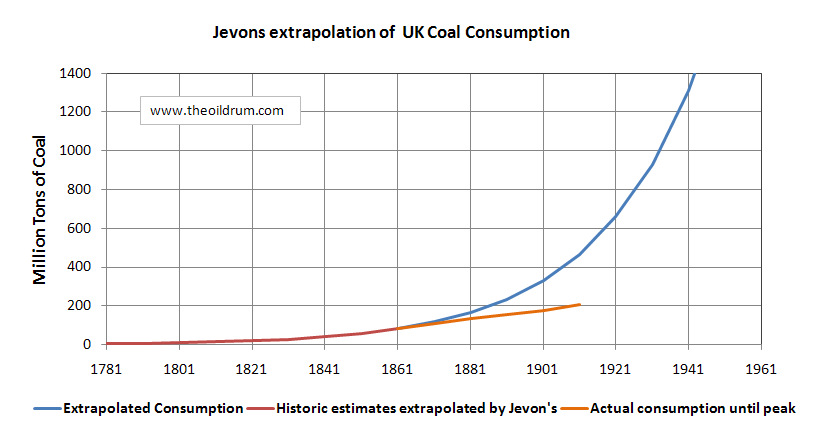

The analysis carried out by Jevons hinged upon two thoughts. First, he assumed that the consumption of coal would continue at a pace of 3.5% per year extrapolated from previous decades. Second, he expected that prices would become too high as mining progressed beyond 2,000 feet towards 4,000 feet of depth. From his calculations he found that an average mining depth of 2,000 feet would more than double the price of coal and that a further doubling could not be borne by the industry.

In his assessment he made the following astute observations that are still qualitatively valid for resource assessments today:

• “And, of course, when Mr. Vivian asserts that South Wales can supply all England for 500 years, he means at the present rate of consumption, which is quite beside the question. The question [of resource depletion] is, how long will South Wales supply us at the present price with the present growing demand?”

• “The higher the price rises, the more thoroughly will the coal-measures be worked, and the more coal becomes workable. As, however, the high price of coal constitutes the evil of exhaustion, the dreaded results are only somewhat mitigated, not prevented. And it would be wholly erroneous to suppose that when once the thicker seams of a coal district have been worked out, we can readily, at a future time, work out the thinner seams, when the increased price of coal warrants it”

• “All then that we can hope from thin seams, or abandoned coal, is a retardation of the rise of price after a considerable rise has already taken place. This will hardly prevent the evils apprehended from exhaustion… If seams of 18 inches are now occasionally workable, the coal-cutting machine may reduce the limit a few inches; but it is evident that seams of less than 12 inches could never be worked while the price of coal remained at all tolerable.”

• “When the general depth of coal workings has increased to 2,000 feet, little or no coal will be sold for less than 10s. per ton, and the choice large coal will have risen to a much higher price. Our iron and general manufacturing industries will have to contend with a nearly double cost of fuel. And when with the growth of our trade and the course of time our mines inevitably reach a depth of 3,000 or 4,000 feet, the increasing cost of fuel will be an incalculable obstacle to our further progress.”

British coal production and consumption

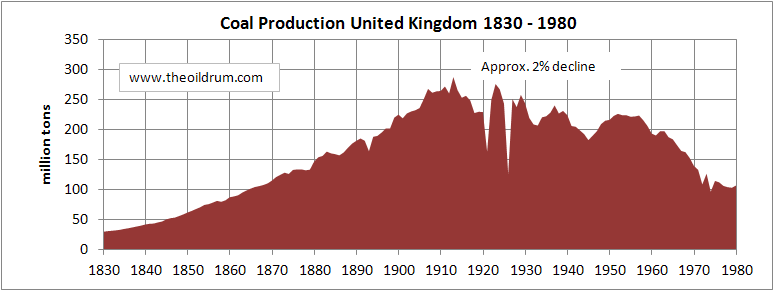

The development of British coal production, shown in figure 1 below, clearly shows production hit maximum in 1913, thereafter declining by around 2% per year on average until the late 1940s. The brief bump in production from 1947 until 1957 was caused by a nationalization of the coal industry. The government injected large sums of money into the sector in an attempt to revive it. The government's production targets were not reached however, and competition by the market made the effort unsuccessful. Subsequently, most of the government’s subsidies were abandoned in the 1960s. Market forces resulted in a rapid rise of oil imports fuelling domestic consumption for both transport and electricity production. After the discovery of oil off the Scottish coast in the 1970s there was even less economic incentive for coal mining. There was and is still a lot of coal remaining in the United Kingdom, but it has at least until present been too costly to get it out of the ground.

Many authors have concluded that the fairly fuzzy peak in British coal production and other coal nations occurred for geological reasons, inferring that coal will behave the same as conventional oil does. Based on this expectation, logistic or Hubbert type models are applied to model “peak coal” in other regions and the world. For example, in figure 3 below from Hook et al (2010), a logistic fit is given to the coal production of three different countries. This approximation mainly based on geology appears to fit well but it is rough, and gives little insights in advance to what will happen, unless you know in advance how much coal will be extracted, which is precisely what is unknown as most countries data is quite poor. In other words, this curve fitting approach gives little information about how economic conditions will influence the amount of extractable coal, and, because of this, we are still in the dark about how production will really progress. Peak coal production forecasts based on present technology range from now until around mid century, depending on uncertain reserve and resource assumptions, as shown by Mohr and Evans (2009). Even more uncertainty is added when technology which is not yet commercial is included, such as underground coal gasification, and its use on offshore coal, as discussed in my previous post on underground coal gasification. These types of advances could lead to an expansion of the coal era.

Looking at coal production from a productivity perspective

In the absence of good data, it is helpful to utilize a range of methodologies, and that is where we can learn a great deal from Jevons. He did not care precisely when coal would hit its peak as his concern was that a point would come when Britain no longer could afford to increase its extraction rate. To ascertain this he looked at geological combined with economic data. The same approach is valid today. We could look at the costs of each coal producing region and look at what we can afford to get out of the ground. How many labour hours, energy, mineral resources, and machines do we need to obtain a lump of coal? Can we afford to utilize so many resources for those purposes? Only few analyses are available in this regard, one of which was made in 2009 for Gilette the largest coal field in the United States.

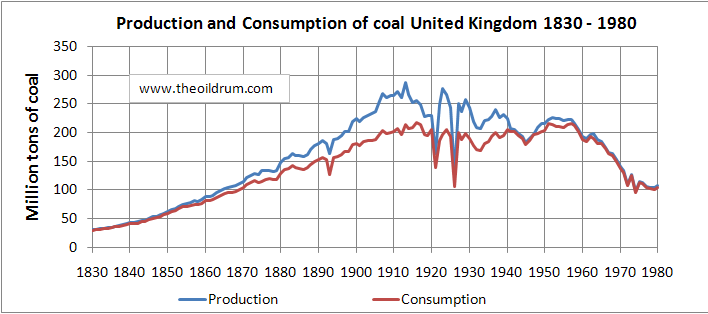

To show that Jevons' methodology made a great deal of sense, I compare a number of statistics. First, in figure 4 below, the production and consumption of coal in the United Kingdom is shown, the difference being caused by exports to mainly the European mainland. The data shows that consumption of coal peaked a little bit later than production as the end of World War I neared. After the war, the British economy declined for a number of years after which growth returned with occasional one to two-year recessionary bumps until the second world war, which similar to the first, coincided with a substantial economic decline. No increase in coal consumption fuelled the inter-war expansion, however, plausibly due to an earlier oversupply, the switch from coal to oil of the British navy after World War I, and an increase in efficiency of British manufacturing and household energy use. Singer (1941) states that:

“We conclude that over the eleven years from 1924 to 1935 the increase in the efficiency of the use of coal- which must in these cases be attributed to direct economy - led to a fall in relative coal consumption by some 38 million tons or 28 per cent of what total industrial consumption would otherwise have been. This is equivalent to a fall, through direct economy and substitution, of 3.0 per cent per annum. It is clear that the 1924-35 period must have played a leading part in the relative fall in coal consumption, which was at the rate of 33 per cent in the last twenty-five years (Singer 1941, p. 170).”

The absence of a domestic need to substantially increase coal supplies coincided with reduced demand for coal exports because of competition from other regions. One region that was especially important in the decline of British exports was the German Ruhr area, where there was an increase in coal production at lower cost due to greater productivity. In addition due to post World War I reparations under the Dawes Plan, Germany would export coal for free to France and Italy as a form of repayment of war damage, at a large disadvantage to Britain. As a result, by the late 1930s, Britain ceased to be a meaningful exporter of coal. Thus the decline in British coal production after 1913 reflected a combination of factors, including both reduced internal demand (from both recession following World War I and from increased efficiency) and reduced demand for exports. If circumstances had been different (for example, greater technological innovation in British coal mining), the peak in British coal production would probably have been postponed substantially.

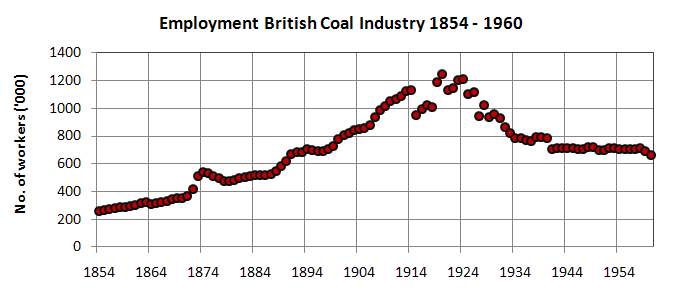

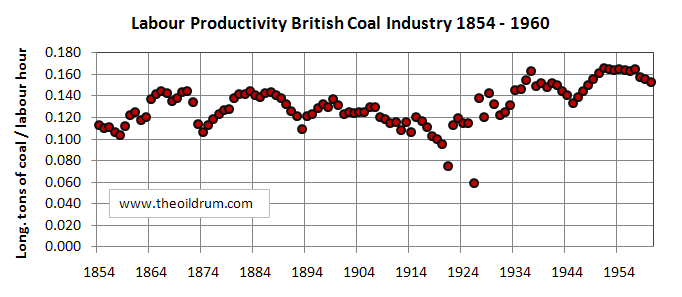

The increase in British coal production since the 1860s, the time of the Jevons coal question, was not caused by an increase in productivity but by employing more labour in the industry. From 1865 until 1913, the mumber of people working in coal mines rose by a factor of 3.5 from 315.000 to 1.13 million people, shown in figure 5. Roughly 2.5% of the population was employed in 1913 to haul coal out of the ground and cut it into usable pieces. In the same period productivity declined from around 0.14 to 0.11 tons of coal mined per hour of labour, shown in figure 6. The reason of the decline in amount of coal mined per hour can be explained from the absence of technological innovation combined with the need to mine increasingly deeper and thinner seams as foreseen by Jevons. About this issue Taylor (1961) remarks:

“…by the 1880's in all but the smallest collieries the steam-engine was in use both above and below ground and its benefits were being felt throughout every coalfield. By comparison with this earlier period the years between 1880 and 1914 have less to show in terms of technological achievement. Improvements were constantly effected in shaft and underground haulage and steam-power gradually gave place to electricity, but none of these changes was by nature or consequence of a revolutionary character. Potentially the most far-reaching innovations of these years were those affecting work at and near the face - involving the introduction of the coal-cutter and the conveyor - but progress in these directions was very limited. As a workable mechanical novelty the coal-cutter was already in existence before 1880, yet as late as 1913 only 8.5% of British coal was mechanically cut and an even smaller proportion was mechanically conveyed (Taylor 1961, p. 59).”

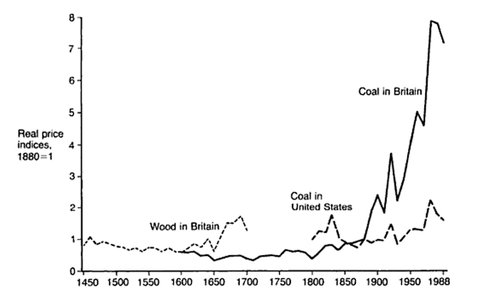

The peak hence occurred because the number of employees could not rise sufficiently as productivity declined. This was aggravated by the temporary loss of employees that were drafted into the army during the first world war, as clearly shown in figure 5. The inability to attract new employees occurred because British mines could not afford to pay a competitive wage and, at the same time, keep the cost of the coal they sold competitive on the international market. British coal prices increased to unseen heights, as shown in figure 7, and the country could no longer compete with coal producers abroad. Data shows that after 1910 British productivity on average was overtaken by Germany, by 1925 it was 6.8% higher, and by 1935 Germany produced 23.6% more coal than Britain in terms of labour output per hour (Broadberry 1998). The coal in Britain became too expensive versus that in other markets and exports dropped.

The lack of proper wages in the face of rising costs of living was so severe that most of the coal industry went on strike in 1921 and 1926, resulting in losses of output of respectively 30% and 50%. The economic situation is described well in Wynne (1913):

“The consequence is that the proceeds of a given output of coal which before the war supported six men had in 1925 to provide a living for seven. The price of coal in the market had not meanwhile risen to the same extent as wage costs per unit of output, and in the period September, 1924, to March, 1925, over 41 per cent of the total output of the British mines was raised at a loss. By May, 1925, this figure had risen to nearly 67 per cent, and during the last quarter of 1925, to 73 per cent, the loss ranging in this latter period from an average of only 2 pennies a ton in the eastern division to 3 shillings and 2 pennies per ton in South Wales and Monmouth, with an average of is 5 pennies a ton for the country as a whole. (Wynne 1913, p. 356-366)”

Earlier in 1919, the work day had already been reduced from 8 to 7 hours underground under increasing pressure by coal unions, further decreasing the amount of output the coal industry could potentially sustain. This caused a further decline in productivity versus other coal producers whose work day was slightly longer than the British. The only option left to solve the imminent situation was to close a large number of unproductive mining areas, raise the wages, and thereby further the decline in production during the 1920s. The move resulted in a rise in productivity, shown in figure 6, but it was too late. Britain as discussed by Taylor (1961) had already fallen behind other producers in implementing the technological innovations, which further contributed to the downfall of the British coal industry. The reason was the conservative nature of the British industry:

“Electricity was looked upon with mistrust by many mines-inspectors until the Home Office Departmental Committee of 1904 expressed opinions favourable alike to its efficiency and to its safety when properly employed; but stringent safety regulations, as well as the conservatism of British mine owners and engineers, retarded the employment of electricity in British mines when it was already widely used in the coalfields of Germany and Belgium. Moreover, as in the use of machinery, the explanation of the shortcomings of British mining lay outside the industry as well as within it. 'Manufacturing electrical firms', it was said, 'do not care for colliery work in this country. They are able to obtain plenty of work in other directions’ (Taylor 1961, p. 59)."

Britain missed the boat and began innovating at too late a date. The rise in productivity since the 1920s, as depicted in figure 6, could do no more than keep production declines at bay. The absence of substantial technological achievements, the increasing cost of coal production, and the rising competition from abroad led to a substantial drop in coal production.

The result of Jevons' publication

Since history unfolded more or less as Jevons expected it, at least for coal, we now know his study had little effect on altering the UK's energy future. Interestingly the coal question was taken seriously quite soon after publication. As a result of Jevons' book, Gladstone, the chancellor of the Exchequer at the time and later prime minister of Britain, commanded a royal commission to examine the coal question in depth and rigour in 1866. The report of the commission took five years to complete and was presented as a three volume work to both houses of Parliament and the Queen of Britain. Its conclusion confirmed the analysis of Jevons, but disagreed with one important point, the extrapolation of past coal consumption:

“The results as summed up in the report to the Queen strikingly confirm the soundness of most of the conclusions arrived at by Professor Jevons, except so far as regards his estimate of the duration of the coal supply. Which, having in view the rapid increase of consumption which had continued up to that time, and the growth of consumption in relation to the increase of population, led him to believe that the total available supply of coal to a depth of 4,000 feet would be practically worked out in the short space of about one hundred and ten years. The author of this paper, however, when consulted by the omission, was of the opinion that the rapid and constant rate of increase assumed by Professor Jevons could not be maintained, "and that the very rapid increase in the annual production of which had hitherto occurred was merely a consequence of the equally rapid and abnormal development of our commercial activity which had followed the introduction of steam power in this country, and that the effect of this initial increase in the annual yield of coal is still perceptible, just as it is in a minor degree in the present rate of increase of our population. (Price-Williams 1889, p.2)”

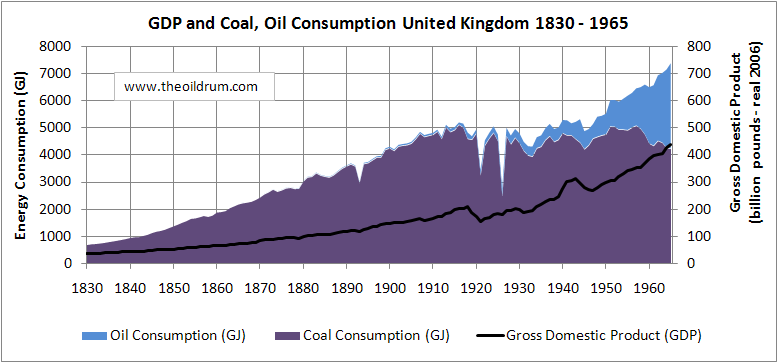

The remark of the commission has been proven correct afterwards. Coal consumption increase tapered off as of the 1880s, shown in figure 8, and coal consumption per unit of economic output increased more slowly as large efficiency improvements took place in the early 20th century as shown by Singer (1941).

Also, Jevons was too pessimistic about the eventual development of petroleum, which in 1865 was only at its infancy:

“Petroleum has of late years become the matter of a most extensive trade, and has even been proposed by American inventors for use in marine steam-engine boilers. It is undoubtedly superior to coal for many purposes, and is capable of replacing it. But then, What is Petroleum but the Essence of Coal, distilled from it by terrestrial or artificial heat? Its natural supply is far more limited and uncertain than that of coal, its price is about 15l. per ton already, and an artificial supply can only be had by the distillation of some kind of coal at considerable cost. To extend the use of petroleum, then, is only a new way of pushing the consumption of coal. It is more likely to be an aggravation of the drain than a remedy (Jevon 1865, VIII.42).”

Fortunately, for the United Kingdom, Jevons proved to be wrong in the effect of the decline in coal production on the British economy. Although the country lost its role as an industrial center, Britain has generally remained prosperous. Jevons expected otherwise: “We cannot long maintain our present rate of increase of consumption…this only means that the check to our progress must become perceptible within a century from the present time (Jevons 1865, XII.29)."

This doesn’t mean that he won’t be correct in the eventual outcome, however, as the oil and natural gas that replaced coal are both running in short supply with UK’s peak production past us. We can replace the word coal with fossil fuels, and Jevons' words unfortunately could ring true today: “the absolute amount of [fossil fuels] in the country rather affects the height to which we shall rise than the time for which we shall enjoy the happy prosperity of progress (XII.29)”, unless we can find a new source of energy, or a way to transition to a happy life with far lower energy consumption and economic output.

References

Broadberry, S.N., 1998. How did the United States and Germany Overtake Britain? A Sectoral Analysis of Comparative Productivity levels, 1870-1990. The Journal of Economic History. Vol. 58. No. 2. Pp. 375-407.

Greasley, D., 1990. Fifty years of coal-mining productivity: The Record of the British Coal Industry before 1939. The Journal of Economic History. Vol. 50. No. 4. pp. 877-902.

Hook et al. 2010. Global coal production outlooks based on a logistic model. Fuel. Vol 89. pp. 3546 - 3558.

Jevons, W.S., 1865. The Coal Question: An Inquiry Concerning The Progress of Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal-Mines. London: Macmillan and Co. [online] Available at: http://www.econlib.org/library/YPDBooks/Jevons/jvnCQCover.html. Accessed August 8, 2011.

Hausman, W.J., 1995. Long-Term Trends in Energy Prices. Ch.3. pp 280-286, In eds. Simon, J., The State of Humanity. Wiley-Blackwell.

Mitchell, B.R., 1988. British Historical Statistics. Cambridge University Press.

Mohr, S.H., Evans, G.M., 2010. Forecasting Coal Production Until 2100. Fuel. Vol. 88. pp. 2059-2067.

Price-Williams, R., 1889. The Coal Question. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Vol. 52. No. 1. pp. 1-46.

Ryland et al. 2010. The UK recession in context - what do three centuries of data tell us?. Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, Vol. 50. No. 4. pp. 277-291.

Singer, H.W., 1941. The Coal Question Reconsidered: Effects of Economy and Substitution. The Review of Economic Studies. Vol. 8. No. 3. pp. 166-177.

Taylor, A.J., 1961. Labour Productivity and Technological Innovation in the British Coal Industry, 1850-1914. The Economist History Review, Vol. 14, No. 1. pp. 48-70.

Wynne, W.H., 1913. The British Coal Strike and After. The Journal of Political Economy. Vol. 35. pp. 364-388.

Rembrandt,

thanks for this excellent analysis. I also highly appreciate his study, which shows that he was far ahead of his fellows (like the peak oilers today).

You are right that he was too pessimistic about the British economy, as he didn't imagine that there were viable alternatives for coal. On the other hand he was right in his concern about the future decline of the dominant role of the British empire in the world (economy): Already in 1870 the United Kingdom's GDP (in purchase-power adjusted International Geary-Khamis dollars) was surpassed by the GDP of the United States of America. And around 2010 (the year of the British coal peak) the United States overtook their former colonial rulers also in terms of GDP per capita. The old "world order" of the dominant British Empire was over.

@Drillo

Thank you for the appreciation of the article. There were a number of people who raised the issue before publication about comparisons between the US and UK GDP, arguing that Jevons was correct on the economic implications (to a large extent) as the United Kingdom lost its role as the worlds superpower to the US. I disagree with this argument as when I read Jevons carefully he talks about the end of growth (end of progress) and the inevitability of falling back in terms of welfare, which clearly has not happened.

"Renewed reflection has convinced me that my main position is only too strong and true. It is simply that we cannot long progress as we are now doing. I give the usual scientific reasons for supposing that coal must confer mighty influence and advantages upon its rich possessor, and I show that we now use much more of this invaluable aid than all other countries put together. But it is impossible we should long maintain so singular a position; not only must we meet some limit within our own country, but we must witness the coal produce of other countries approximating to our own, and ultimately passing it.(Jevons 1865, p. 4)."

"Firstly, have they taken time to think what is involved in bringing a great and growing nation to a stand? It is easy to set a boulder rolling on the mountain-side; it is perilous to try to stop it. It is just such an adverse change in the rate of progress of a nation which is galling and perilous. Since we began to develop the general use of coal, about a century ago, we have become accustomed to an almost yearly expansion of trade and employment. Within the last twenty years everything has tended to intensify our prosperity, and the results are seen in the extraordinary facts concerning the prevalence of marriage, which I have explained in pp. 197-200, and to which I should wish to draw special attention. It is not difficult to see, then, that we must either maintain the expansion of our trade and employment, or else witness a sore pressure of population and a great exodus of our people. (Jevons 1865, p. 7)

"But then I must point out the painful fact that such a rate of growth will before long render our consumption of coal comparable with the total supply. In the increasing depth and difficulty of coal mining we shall meet that vague, but inevitable boundary that will stop our progress. We shall begin as it were to see the further shore of our Black Indies. The wave of population will break upon that shore, and roll back upon itself. And as settlers, unable to choose in the far inland new and virgin soil of unexceeded fertility, will fall back upon that which is next best, and will advance their tillage up the mountain side, so we, unable to discover new coal-fields as shallow as before, must deepen our mines with pain and cost. (Jevons 1865, IX 18)."

"So far then as our wealth and progress depend upon the superior command of coal we must not only stop—we must go back. (Jevons 1865 Ix. 20)."

Hey hey Rembrandt,

I remember being uncomfortable with a claim that Jevons made about the impossibility of England importing coal from other nations in The Coal Question. It has been a little while since I read it, but I remember him saying that ships left England full of coal and returned full of goods. Then he stated that importing coal wouldn't work for England. Although I was impressed with his insights and understanding, especially for the time, I thought that he dropped the ball on this point. After all, the rest of Europe was growing while importing British coal.

So I take Jevons's claims of an absolute decline with a grain of salt, but he did predict that the USA would overtake England's economy because of its larger coal resources. And I have to agree; at the height of British power England was producing and consuming half of the world's coal; at the height of the American empire the USA was producing and consuming half of the world's oil; and the Chinese are presently producing and consuming half of the world's coal and everyone expects them to eclipse the USA in very short order.

Yes, my thanks also to Rembrandt for this excellent summary.

There is an interesting period roughly 1911 to 1947 when British / UK energy consumption did not increase much in total, even though there was a rise in population. 'Energy' only 'took-off' again in the post WWWII 'petroleum age'.

Some of the charts end 20 or more years ago e.g. Fig 4 for UK consumption & production ending in 1980. Coal production is now less than the comparatively insignificant 20Mt/yr (see Figure 3 for confirmation), and in the case of UK, this includes a sizeable proportion from surface mining using 'economically viable' technology that was not available in earlier years. We have continued to use substantial coal in recent years, and have imported up to 50Mt per year (2006) for electricity production.

The population of UK & NI rose during the 'energy stagnant' period, from around 41M in 1911 to 50M in 1951 [edit]. (By 1981 population was just over 56M. There has been a subsequent jump in population from 1990, and especially from 2000, in England to a UK total of about 63M today.) Per capita energy consumption in UK was remarkably not very different during the first half of the 20thC, spanning a period of uneven modernisation that included the further expansion of London as a centre of both population and industrial manufacture, as well as the building of a country-wide electricity grid, paving of roads etc.

[small EDIT: per capita 'energy use ' in UK was already at a 'high' point by 1900 and higher than obtains in most of the world today.]

"And after Jevons died, in 1882, his study was discovered to be filled with from top to bottom with stacks of scrap paper. Soon enough England would be running out of paper, too. He didn't want to be caught without."

-Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A story of economic discovery, David Warsh, 2006, p 71

On the other hand, as Warsh notes, Jevons did make some useful contributions to marginalism. In 1871, Jevons wrote: "The nature of Wealth and Value is explained by the consideration of indefinitely small amounts of pleasure and pain, just as the theory of Statics is made to rest upon the inequality of indefinitely small amounts of energy." Warsh, 2006, p 69

"Statics" referred then to that branch of physics "dealing with forces and masses in equilibrium".

A techno-optimist can point to this history in support of the argument that we will find something to replace oil. But it is questionable whether there is anything in the pipeline that is scaleable, abundant and has a decent EROI.

Problem with oil that everyone on this site knows and the general public including most of the techno-optomists forget, is just how many things we need to find subsitutes for besides just energy to replace oil.

Graphene is shaping up as a substitute for everything from indium oxide (as a transparent conductor) to steel. It's no more limited than the supply of magnesium (harvested from seawater). For that matter, magnesium is a reasonable substitute for aluminum in many applications.

Uhh... graphene is just structured carbon. The feedstocks for producing it can come from stuff like ethanol and methane. I mean, I make the stuff in the lab currently. However I wouldn't rely on it for a replacement for steel. Maybe ITO, and one day silicon, once we get a good toolbox for it, but graphene would have to be in a composite for structural applications.

Or maybe it could be used as a reminder to some that when making predictions about the future, humility is in order.

"Predictions are hard, especially about the future."

Neils Bohr?

Nick - Not possitive but I think it was basebal player Yogi Beara

Oops. :)

Some techno-optimists might want to replace oil. Others of us say, why bother. Let's do things differently.

Take, for example, all the wealth we enjoy because of the division of tasks. Burning oil in internal combustion engines doesn't create that wealth; rather it is specialization and more-or-less matching workers with jobs that equal their skill sets. Mobility is important to this end, and for that we have feet, bicycles, and various means of electrified transport.

Right, I tend to be techno-hopeful. At least that helps when I contemplate how to prepare for retirement in 2040. The necessary transformation is not about finding a petroleum substitute and running along same as we've been for the last forty years. It's about getting down to the essence of what, how and why.

I once heard about a Canadian fishing company that would catch fish in Canada, ship them to China to be filleted and canned. Then the company would re-import the canned fish to be sold in Canadian supermarkets. Such is the logic, or should I say, logistics of this mindlessly efficient global economy. Of course, the play here is to trade-off energy intensive transportation costs for lower cost labor intensive processing. I get the economics of this, but at the same time it gives me pause. What are we really trying to accomplish? How can we forge a more direct route between those who catch the fish and those who eat them? Perhaps only a real stiff energy crisis could help us recover a bit of economic simplicity. It's the ultra "efficient", hyper complex stuff that will collapse first.

So what do I want to invest in for retirement? I want to see biofuels and renewable chemicals displace petroleum. So I'm investing in that for the long run. But I think companies with energy efficient logistics will fare better than others. FedEx in the US overnights everything to Atlanta and back out for delivery in the morning. Imagine that a 6000 mile trip to send a package from Santa Monica to Los Angeles! This is one idea of efficiency. For another, Norfolk Southern is able to ship a ton of freight by rail over 300 miles on a gallon of fuel, and without adding an ounce of congestion for commuters idling in the freeways just trying to get to work. Trains are 19th century technology, but they get the job done. I suspect they'll be moving the economy along long after FedEx and long-haul truckers have gone out of business. With any luck, I'll be able to visit my grandkids by train someday. Dare to dream.

James

energy intensive transportation costs

Water transportation is extremely energy efficient - that's part of why such schemes work. It's also why inter-country water-based trade often replaces intra-county rail-based trade: e.g., China might import coal from Australia rather than expand coal moved by rail from western China.

Maybe yon a ought to invest in a fishing pole.

And what type of fishing pole? One like my Grandfather had - built of Bamboo with cloth string - or a modern high technology fishing pole composed of hi-tech materials with oil-derived mono-filament line? The collective problem we all suffer is that we cannot imagine life without the benefits of hi-technology. Let me know when you can fashion your own fishing pole without modern materials - using bone as a hook - twisted plant fibers as line - and a suitable piece of wood as a pole.

A Canadian who would have made a modest but livable wage processing that fish at home has to either find a better job-one that he may very well never find due to a lack of qualifications-or take a lesser job , such as flipping burgers or cleaning hotel rooms-if he can find one of those.

The result:Canadians who can afford fish pay very slightly less.A whole bunch of canadians who would have made a living processing fish or working in support industries, such as local industrial supply houses, etc, have provbably wound up dependent on whatever safety net programs are available locally to them.(I'm presuming some such programs are funded and operated at lower than the federal level.)

Just about anybody who is even remotely acquainted with such programs simply must understand and acknowledge that they cost considerably more to administer than they deliver in benefits.

The NET result to the typical Canadian is probably that the slight savings associated with the purchase of the fish is offset by a substantial margin-perhaps several times over- by the cost of maintaining a more robust and intrusive welfare state.

Furthermore such programs tend to become set in stone;all bueracracies develop constituiencies of thier own.

Right now I personally know of two couple living within walking distance of my own home who "live in sin", as the preacher puts it.

I personally "lived in sin" with both of my own former wives, and wouldn't mind doing so again if I could attract another desirable woman , and do not consider this to be grounds for moral judgemebnt of any individual or couple.

My point is that such programs can be manipulated-both these couples gain considerable amounts of in kind income such as medical care, school lunches, etc, by the simple expedient of the man maintaining a seperate address-a nearby room with some stuff in it where he gets his mail.Such rooms can be had from an accomodating friend for nothing whatsoever.

You can legally spend as many nights and days away from "home " as you please-nobody ever asks any questions, and it would be virtually impossible to prove the fraud.

In the end, this whole globalism thing is probably a net loss for an advanced western economy.It certainly has had a hell of a lot to do with getting us into a spot where financial collapse is a very real danger.

A TRUE conservative president or congresswould have done serious things about problems such as importing oil when it was still popssible to do so, and about running up a foriegn debt that will eventually have to be repudiated at gunpoint.

There IS a difference between a conservative -a real one-and a republican.

That leaves me with a thought. Some jobs will return as the price of oil soars. The cost of shipping will increase as the oil price rises and it will become more economical to process the fish in Canada than China so those jobs will be recreated. The same goes for other industries. Now, how far will the return of jobs go to offset the loss of other jobs?

NAOM

My point is that such programs can be manipulated-both these couples gain considerable amounts of in kind income such as medical care, school lunches, etc, by the simple expedient of the man maintaining a seperate address

Why do these programs care about whether they have a roommate, or live alone?

The problem is my bicycle is high tech. There is no way I could ever duplicate it, or build it without fossil fuels and high technology. Advanced, lightweight alloys, TIG welding, kevlar beads. Bicycles depend upon high technology - from the machining to the individual parts. Bicycles will not fit into a future that does not have ample supplies of oil.

I didn't realise ALL bicycles HAD to be made from "high technology". Unless you think that the 1870's were the height of technology.

Wooden frame bicycles

High tech doesn't need fossil fuels or oil, in the long run. Machining is powered by electricity; plastics only need a source of hydrocarbons, and can be reycled.

If liquid or gas fuels are needed for relatively tiny uses like welding then we'll synthesize them. They may cost $3/liter, but for such small uses, it doesn't matter.

Hi Rembrandt,

Thank you for your thoughtful post. I think you are letting the Royal Commission off lightly with their comment:

"The results as summed up in the report to the Queen strikingly confirm the soundness of most of the conclusions arrived at by Professor Jevons, except so far as regards his estimate of the duration of the coal supply."

The Commission gave three scenarios in their report:

(1) Exhaustion in 2147, with consumption in that year of 943 million long tons

(2) Exhaustion in 2231, with consumption in that year of 616 million long tons

(3) Exhaustion in 3144, with consumption in that year of 115 million long tons

All of these scenarios are fantasies.

The 110 years the Commission attributes to Jevons would get us to about 1980, between the miners' strikes against the Heath and Thatcher governments. This was a reasonably accurate estimate for the "duration of the coal supply."

Regards,

Dave

I also found this very interesting. I notice that you mention that much coal remains in the UK but is not worth extracting Could extracting this coal become viable at some point in the future? Given the rapid decline in oil and gas production I wonder if the British might become encouraged to re-consider coal.

EROEI, but nothing is off the table. Efficiency and technology has allowed for the continued production of some previously nonviable deposits of fossil fuels. The incremental utilization of "renewable" energy assists the process. Humans are smart and wise.

There are solutions to our problems. Those solutions will work, but we are not going to choose them.

Humans are smart but not wise.

PS appologies if this was sarcasm and I missed it.

So we are smart. So we figureout a way to get the energy of that remaining 75% unused coal up. But if we are WISE, we leave the carbon atomsdown there, rather than letting themescapeto the atmosphere.

'Smart' and 'wise' are not synonymus.

It wouldn't surprise me that in the future the same type of situation will arise in the UK as what happens in the Ukraine:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mz_RREduic8

I am assuming this analysis takes into account the exporting of UK manufacturing production overseas when dealing with how well Britain adapted to peak coal flows, all powered by another cheap energy dense fossil fuel - crude oil ? Had crude oil production not increased as a more beneficial fuel supply for global transportation, one wonders if global trade growth would have been as great as it has been, and therefore how much UK CONSUMPTION would have been meet with UK production during declining coal production.

Hi platinumshore,

Many of the traditional markets served by coal in the UK are now handled by natural gas, but the consumption of coal is still substantial. However, most of the coal is imported now. In 2010, the UK produced only 35% of the coal it consumed.

Dave