Tech Talk - Gulf of Mexico production and hurricanes

Posted by Heading Out on August 1, 2011 - 11:00am

The summer brings back hurricane season, with the threat that such storms bring to the oil and gas well operations in the Gulf of Mexico. And the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has noted that

The Atlantic basin is expected to see an above-normal hurricane season this year, according to the seasonal outlook issued by NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center . . . 3 to 6 major hurricanes (Category 3, 4 or 5; winds of 111 mph or higher)

The lessons of this vulnerability were, perhaps, more than most years, evident in 2005. The first sign of problems came with the arrival of Hurricane Dennis in July. It was a storm which severely damaged the BP deep water Thunder Horse drilling platform.

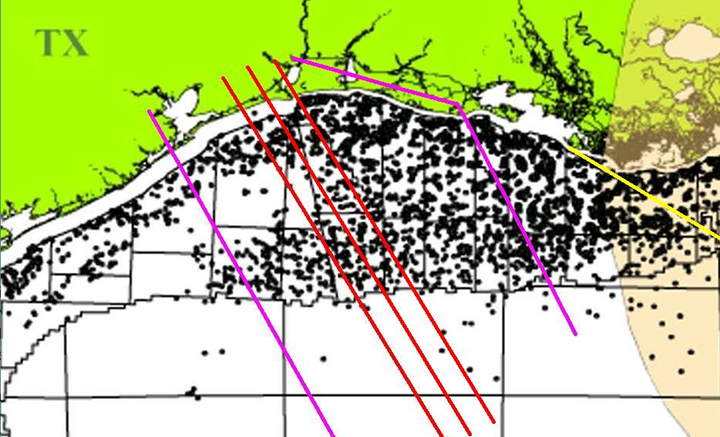

As that season wore on, the vulnerability of the platforms in the Gulf and the refineries that border it, were exposed in more intensity with the passage of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. These threats and their analysis were one of the factors that helped, in that formative year, to bring an audience to the pages of The Oil Drum. The Gulf is now home to thousands of wells which, as the evidence from the Deepwater Horizon disaster last year reminded us, has moved further and further away from shore. That vulnerability is perhaps illustrated by a map showing the path of Hurricane Rita through the oil platforms off the Texas and Louisiana coasts.

Back in the 1930’s and ‘40’s it was the very gradual deepening of the seabed in the Gulf that allowed the first oil drillers to venture through the swampy regions of the Mississippi Delta and then on out into the waters of the Gulf. There had been some drilling from piers out in California and similar constructions were also tried along the Louisiana shore as the prospects for success tempted companies away from the coast. However, as they did so the rigs faced the challenge, as they do today, of surviving in regions where hurricanes are not uncommon. The industry was helped in this development since there were no major hurricanes that moved through the regions of most intense drilling, from the first wells in 1945 until 1964 when Hurricane Hilda arrived. And even when that hurricane struck on October 3rd, it only damaged three locations, at Eugene Island and Ship Shoals 149 and 199, with a total of some 11,869 bbl of oil being spilled due to the storm.

The first pier-based platform had been built out into the Gulf of Mexico at McFaddin Beach south of Port Arthur, Texas after having been approved by the Secretary of War, on July 8, 1937. The pier was a mile long, with three rigs at the far end, but it only drilled dry holes and was destroyed in a hurricane in 1938. More widely recognized was the first well to be drilled out of sight of land. This was the Creole platform near Cameron, which was a mile out-to-sea, an hour-an-a-half trip by shrimp boat at the time. The water was only 18 ft deep and the well, initially drilled by Pure Oil and Superior Petroleum, (later Kerr McGee, and then Anadarko) sat some 15-ft above the water level. Initial production was 600 bd from a depth of 9,400 ft. It was damaged by a hurricane in 1940, but survived and produced more than four-million barrels since through directional drilling.

As was the case with California, there was initially some controversy over who owned the rights to minerals off-shore and in 1953 Congress passed the Submerged Lands Act, which gave the rights to the states for the first three miles offshore (the range of a smooth bore cannon at one time) and then the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act which gave the rights for the more offshore land to the Federal Government. This settling of the disputes encouraged further drilling and while there were already 70 rigs drilling at depths up to 70 ft of water, the years after 1953 saw the development of a variety of different rigs for drilling in ever deeper water. Designs to cope with hurricanes also progressed, so that by the time of Hurricane Flossy in 1956 rigs were relatively safe. It was followed by Audrey in 1957, ranked as the sixth deadliest hurricane in US history, which came ashore at Cameron, and killed 416 people, but caused $16 million in damage offshore, with no fatalities.

Technology was, however, allowing rigs to work in ever deeper water - 100 ft of water in 1957, 225 ft by 1965, and 300 ft in 1969. With this increase in range came increased production, which had reached 2 mbd, but it also exposed more rigs to the threat from larger storms. Hilda, formed in 1964, caused $100 million in damage and effectively destroyed 18 platforms,; Betsy in September 1965 had the distinction of financially impacting a future President of the United States.

On September 9th, the day Hurricane Betsy struck, MAVERICK was located 20 miles off the Louisiana Coast in 220 ft of water. The following day an inspection showed Zapata’s three other rigs were undamaged, but the MAVERICK had vanished. This was the largest single loss that the domestic offshore drilling industry sustained in this or any other hurricane. . . . The MAVERICK loss was a substantial one for Zapata. This was our newest rig and one of our very best contracts. . .

(George H.W. Bush, “My Life in Letters and Other Writings.”) (The insurance check was for $5.7 million).

Camille in 1969 was the largest storm to hit the USA in the 20th century. It did about $100 million in offshore damage, including sinking three up-to-date rigs designed to survive those storms. (Camille was a Category 5). Onshore the damage exceeded $1 billion. This was the hurricane that taught the industry that they had to design rigs that could not only withstand waves more than 70-ft high, but has also to consider that the seabed itself might move under the force of the storm.

Fortunately such storms have proved to be relatively rare, and the “three strikes” of Dennis, Katrina and Rita in 2005 have not been repeated since. Yet the industry remains highly vulnerable to such storms. As the second figure shows, the Gulf has become increasingly filled with production platforms. In 2008, this region was hit by hurricanes Gustav at the start of September and Ike two weeks later. Even though these were weaker storms, their impact was significant.

Effective August 2008, there were more than 3,800 production platforms in the Gulf, ranging in size from single well caissons in 10 feet of water up to a large, complex facility in 7,000 feet of water. The MMS estimates about 2,127 production platforms were exposed to hurricane conditions from Gustav and Ike, carrying winds greater than 74 miles per hour.

Final results of the agency’s assessment of destroyed and damaged facilities from these two storms indicate that 60 platforms were destroyed. These included some platforms that had been reported earlier to have extensive damage.

In comparison, 115 platforms were destroyed by the Rita-Katrina wallop in 2005.

The platforms designated as destroyed following Gustav and Ike produced 13,657 barrels of oil and 96,490,000 cubic feet of gas per day, or 1.05 percent of the oil and 1.3 percent of the gas produced daily.

Part of the reduction in damage came from lessons learned from Katrina/Rita.

Mobile Offshore Drilling Units (MODUs) that previously had to have eight mooring lines were now required to have 12 and, in some cases, 16 mooring lines,” Angelico said. “In ’08, 18 moored MODUs were in the path of hurricane force winds, and two went adrift, which represented 15 percent of the rigs out there. In Katrina and Rita, 63 percent of the rigs went adrift.’

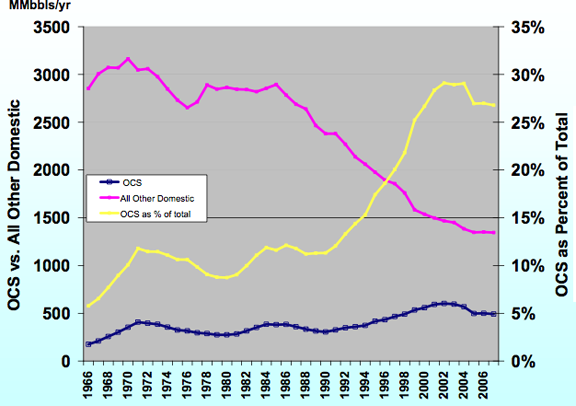

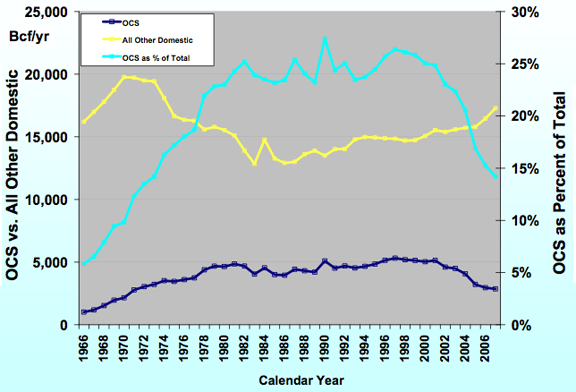

There are additional impacts from these storms. The Gulf continues to produce about 27% of the nation’s oil, and 15% of the natural gas. Those fuels must be brought ashore and, in the case of oil, refined. Refineries lie inshore all along the Gulf Coast, and if flooded can take months to be brought back on line. Given the growing reliance that the country places on production from these regions makes us all vulnerable to the season.

Last October, OCS crude and condensate production averaged 1.52 mbd, which comprised 28% of the estimated US production.

Last October natural gas production averaged 5.6 bcf/day which was 8.9% of estimated national production.

There is a significant production from smaller, older wells, while the new fields are found in deeper waters further into the Gulf, and so that is where I will venture next time.

Deep Water: It's not just the end of "cheap" oil,

it is also the beginning of "unreliable" oil,

and the beginning of "ocean-polluting" oil.

The poor old Thunder Horse was a great photo opportunity, its ballast problem was as much man made as due to weather.The rig was only months out from the ship yard, and for some reason the ballast valve logic was installed with fail to open, so when the power failed valves opened instead of closing, and the rest was history.

No doubt there are some other versions of the story and anybody who was closer to the action I please hear and be corrected, but it was defiantly a software glitch that was allowed to manifest itself due to the evacuation caused by "Dennis"

FOR ALL A slow post so I’ll offer a bit of insight as to why companies shut down ops so quickly when a hurricane is just getting close to the GOM. Not sure what the head count is today after the permit slow down but in the past there were up to 35,000 hands out there on a given day. The primary people movers are the choppers. Obviously that fleet isn’t designed to move all the hands in over a short period. Given it can take 1 to 2 days to shut down ops and secure the rig they can’t wait too late to pull the trigger.

A more specific example: many years ago Conoco had a well going down from a drillship. A storm was on its way into the GOM but they were at a critical stage so pushed on…a little too long. Derrick man: the hand who works about 100’ above the drill floor on the “monkey board”. He facilitates the racking of the 90’ stands of drill pipe while going in and out of hole. The forward wind gusts came up faster than anticipated. While trying to pull the drill pipe out a wind gust blew him off the monkey board. His safety harness saved him but the wind blew him back and forth thru the derrick for a bit. He was finically able to grab a stand of drill pipe and they lowered him down to the floor. They had to carry him off the floor. He wasn’t hurt but was in too much shock to walk. I’m sure one or two heads rolled over the incident.

Obviously after such a near miss Conoco management had no trouble pulling the trigger quickly next time a blow headed their way.

Fun fact: the most famous GOM chopper pilot would be my Dad's favorite songwriter, Kris Kristofferson.

There's a story about Kris touching down in Johnny Cash's front yard, jumping out with a demo tape in one hand and a beer in the other. He denies ever drinking while flying...the Man in Black wasn't home but he did talk to June.

When I started in '75 chopper pilots were a different breed than today. Most of my drivers were VN vets. Rules were a bit loser back then also. Made for some interesting flights. Didn't screw around much around the rigs but getting back to the bank was a different story. Almost all enjoyed coming in like landing on a hot LZ. Particularly liked rolling over and dropping the last 2,000' as fast as possible. Seen more than one hand puke on his boots. LOL. Fortunately my system was somewhat immune. No matter how wild I'd rather a 1 hour chopper ride than a 16 hour workboat ride...especially in rough seas. Lost my lunch a few times. Could usually control myself...until a half dozen guys started losing it. The sound and smell just too much to handle. And no...against safety policy to go out on deck while under way.

BTW folks: more hands have been lost in chopper accidents than rig accidents since they became the main transport mode. A couple of years ago while on a rig near Morgan City, La. a chopper crashed very shortly after taking off from a shore base in heavy fog. Lost all onboard...11 hands including pilots. Speculation they hit a flight of geese. Heard the crash but because of the fog took a while to find them. A very sad day in the oil patch to say the least.

Flying with the old Vietnam vets was a bit of an experience, they always flew like they were under enemy fire and after we got off the helicopter we often wondered, "Was that a normal landing, or were we shot down?"

But as in many fields, there are a lot of old helicopter pilots, and a lot of bold pilots, but not many old, bold pilots. The surviving experienced ones are more safety-conscious, give long, detailed safety lectures before take-off, and often say as we're landing, "Take your time getting off, we're not under enemy fire," because a lot of passengers still behave that way.

I could talk about the time I was hiking through mountains in a heli-skiing area, and found a helicopter rotor blade lying in the grass, but explaining it would take too long. Suffice it to say that flying in helicopters is not totally safe, but neither is skiing on avalanche slopes, and if I was too afraid to do one, I wouldn't do the other, either. The same applies to oil drilling in the GOM.

Rocky - Don't know when you last flew offshore but they have gotten very serious about chopper safety these days in the GOM. Landing on the rig: no seaside exit of chopper; walk path painted on pad; fire control standing by with extinguisher; one or two landing hands directing you to stay on path and hauling your bag off the pad; chopper landing safety officer observing everything.

I imagine stories of hosing off the pad after some careless hand walked into one of those invisible tail rotors eventually got their attention.

How safety conscious these days: came off the chopper pad and going down interior stairwell on an ExxonMobil job. The safety officer at bottom watching everyone coming down. During the hallway checkin he complimented me for keeping one hand on the rail as I came down the stairs. Then ordered the 3 other hands into the conference room to watch 2 hous of the same boring safety films we have all seen countless times. Their punishment for not keeping one hand on the rail while coming down.

That's my background. Needless to say my safety protocols have irritated a lot of hands. But I've never had one killed or badly hurt on my watch. Would really like to keep my record intact till I retire in a few years.

Just wondering, since you mention those handrails every now and then. In almost any big city there are plenty of wide stairways in large buildings, train stations, and the like, used by thousands of members of the public every day. At busy times the handrails may be well out of reach for many or even most. This might even be encountered to a lesser degree on ferries - more handrails, stairways divided them, but still someone going down the middle of one of the ways might not quite reach one. And it all doesn't seem to engender a whole lot of fuss, at least not fuss that's heard in public.

So, apart from possibly a storm rocking everything heavily, is there something intrinsically dangerous or unusual about those rig stairwells?

Paul - In 36 years I've never been on an offshore rig that swayed enough to need to grab a handrail. That's not the reason for the protocol. Hands are up and down narrow stairs all day. So why use the rail? Very simple: there's no reason not to use it. Nothing more complicated than that. If you trip and fall down the stairs the first thing the safety officer will ask of witnesses: was he using the rail? If they answer in no then there's about a 50/50 change the hand will get run off. Akin to the rule with old sailing ships: one hand for you...one for the ship.

The logic is simple: if a hand can't follow a simple and easy safety rule then why should he be trusted to follow the more difficult safety procedures. I know it can be difficult for the public to believe safety is a serious issue with "Big Bad Oil". But operators are easy targets for litigation. Get a number of safety violations on your record you get fired. Otherwise if you have a serious accident and hurt/kill another hand the issue would be why you weren't fired because of your record.

Just standing in the wrong spot on the drill floor at the wrong time can get you written up. Just 2 years after I started working a hand running casing stood in a danger zone when they were lifting a joint into the derrick. Casing fell and killed him instantly. After the tool pusher used a shovel to move his body onto I tarp I helped carry him off the floor. And then they continued running the casing. In those bad old days you just cleared away any problem and just carried on…time is money. Today the entire operation would be shut down and the entire crew (both 12 hour shifts) replaced and sent to counseling. An accident investigation team would keep it shut down until their work was done. In the bad ole days hands were just replaceable chunks of meat in steel toe boots.

So now you might understand why I can be a world class *sshole when it comes to safety. After I helped the tool pusher all I could do was sit in my car and cry for a few hours. I've lost more than one contract because I wouldn't work with unsafe folks. Nothing heroic on my part...just never wanted to sit in my car and cry again. If I did I wasn't sure I would ever have the nerve to go back on a rig. Some events make lasting impressions, eh? LOL.

In the much older, bad ole days, my great-grandfather (who died almost 20 years ago at the age of 97) drilled for oil in Oklahoma. He used to tell about convincing one company he worked for that preventing injuries was more cost-effective than training the new guys to replace the dead/maimed ones. He was very proud of the safety record he'd achieved in his lifetime of work in the oil-patch.

awh - Good man. I'm sure it was a struggle for him to some degree. Even when I started in the 70's the attitude towards injuries was still a bit cavalier (read: *ssholes) in some companies. Back in his days I'm sure some companies would have classified him as a "troube maker".

My sympathy. I was in a car with a 24 year old male co worker as the driver. He drove like young men often do, and after a bunch of rides we had the accident. I woke up at the hospital without any memory, but got away with one month sick leave and 20 scars in my head. In a car I am now the driver safety gestapo, but those 20 stitches gives me a possition to tell people around in those issues. "Been there, done that, got the scar".

For comparison

http://thereifixedit.failblog.org/2011/07/28/white-trash-repairs-close-e...

NAOM

Back when stairways were only 2'6" or 3' wide, every roughneck leaving the floor always used both hand rails, unfortunately they had trouble keeping there feet on the stairs, real fun especially if there was some wet mud or grease on the hand rail. These days with our 5', stretcher width stair, people have a tendency to walk down the middle of the stairs and forget about the hand rail. It is a constant struggle to get people to comply.

It is fascinating how a small change in the environment, knocks onto change their habits.

It certainly is a different oilfield today than what it was when I started.

pusher - And attitudes vary greatly by culture. While drilling offshore Africa with native floor hands (required by the local govt) for ExxonMobil it was nearly impossible to keep the hands wearing their gloves and safety glasses. Just a macho thing. Finally during the regular Sunday morning abandon ship drill XOM shut the entire rig down. Everyone (including expats) had to stand on the rolling chopper pad for 5 hours listening to safety speeches. Needless to say the expats were very PO'd. XOM finally sent 2 full time contract safety officers to the rig (at $4,000/day). How bad was it in the beginning: first abandon ship drill most of the natives (the ones that could find their lifeboat stations) showed up in shorts, flip flops, no hard hats or life vests. And this was after spending 3 days at the shore base doing safety and team building exercises.

One last note on safety for the non-oil patch: STOP cards. Every offshore rig has a box containing STOP cards to report unsafe conditions/hands. Some companies take it very serious: require each hand to turn in so many per month or you get to watch the same boring safety film for the 100th time. Often on Sunday afternnon during the football game (a very heavy punishment for some. LOL). And you couldn't just make something up. So it forced hands to look for potential problems. Didn't need to be a biggie: a lose hand rail, leaky pipe, slight hand cut, etc. I always kept a pocket full to keep the companyman happy. Kissing a little management butt can be handy for a contract worker. LOL.

BTW: At the end of my first 28 day hitch they pulled the BOP because they thought they may have had a saltwater leak in one of the pods. Pulled the BOP apart and SURPRISE: The housing of one master control valve was EMPTY. A piece of crap Russian drillship that apparently falsified the initial BOP test. I mentioned it before: the only real bedtime nightmare I've every had on a rig in 36 years was on this job. I dreamed the ship was rolling over and but my feet thru the ceiling tile from my top bunk. Did two more hitches (one 43 days) and then quit. I didn't mind giving up the 30 hour commute either. I was happier driving 7 hours to Intracoastal City every week. LOL.

Rockman,

You peak my interest with this Russian drillship of yours off Aftica, I spent 6 years on one of the Gusto drillships that spent most of its life working for a french company before being bought by a George Soros company, but that is another story. I suspect the well you were drill was off EG. The company I worked for planned to monopolize the deepwater market as it stood in 1995-2000, but was over taken by events, people built new ships. The Russians only had 3 ice class drillships, would I be correct in saying the rig was owned by a Dutch company?

Talking about Equatorial Guinea, we were suppose to drill a wildcat there in 1999. We went to Cape Town for a refit, fueled and ready to sail, the Sheriff came running up the gang plank, declaring we were under arrest. The company owed some bills in another country. Anyway we and the rig stayed in port for 8 months, great place Cape Town. Anyway the well we were going to drill was for Triton, and it was the discovery well for the field that Exxon later bought. So that must go down as the biggest oil find I didn't make.

pusher - Yes...EG. Maybe I'll remember the name of that Russian drillship in a bit. Found this: http://www.oilrig-photos.com/countries.asp?id=67. But the Songa Saturn doesn't sound familiar. And this is a pic after they started drilling in EG again. There's also a shot of the FPU at Zafiro wher we drilled - 25 million cuft per flared. heres the Jade platform I drilled one well from: http://www.oilrig-photos.com/picture/number1963.asp. Last well XOM drilled there before sending it to Angola. It had been a DS converted to a freighter converted back to a DS. Not sure who owned it at the time but Dutch sounds right given how cheap they were: gave the Russian crew a single $30 call card for everyone to uses for a month. Needless to say their attitude wasn't very good. Especially after I broke those ceiling tiles. LOL. Eventually they had the catering company stop serving coffee to save money. You can imagine how that went over with Coonasses...and me. Eventually all the expats had their own pots stashed away.

Rockman,

Try these on for size, Muravlenko http://www.rigzone.com/data/rig_detail.asp?rig_id=2

Or Valentin Shashin

http://www.rigzone.com/data/rig_detail.asp?rig_id=1133

Or the Perigrin I

http://www.rigzone.com/data/rig_detail.asp?rig_id=679

These were all DP vessels. Of course it could have been anchored but I thought the water there would have been too deep.

Pusher - yep...5,000'+ WD. Perigrin sounds familiar and the pic looks right.

"Could usually control myself...until a half dozen guys started losing it."

Ah yes, Sympathy Puking, the maneuvering room was famous for that. Four or five guys in close proximity, and you can't leave. Having round hulls, submarines have a really sickening roll pattern. On a faster surface transit, the single screw gives the engine room a pronounced figure eight pattern. And you don't do enough surface transits to really get used to them.

Rock, I think the chopper that your talking about went out of PHI Amelia and went down in the Bayou Black area. The last word I saw in the Houma Courier was that it hit a Red Tailed hawk. The area also has massive amounts of ducks, some geese and many eagles during winter.

I had a hairy ride coming in the other day on an S-92 with 17 souls on board. It made me re-think my career choice.

Oh yeah by the way the head count in the GOM is actually not quite enough to fill all the needs of the oil patch at this time. We have several deep water new builds coming into the GOM soon and we don't have the hands.

I don't know if I mentioned this previously, but on my last assignment our deep water company reps spent most of there time in the smoke shack(smoking area) texting on their I-phones and when service hands or tool pushers would come by, they would as "hey man what's going on out there?". These guys had no deep water experience and their Houston management seemed to be complete morons. I'm having a hard time with this, because after last years incident I was really hoping for change I could believe in.

wildman - Yep...came out of Amelia. BTW: speaking of lightweights in the field - did I tell you about the FESCO hand tesing one of my wells a couple of months ago. Prior to FESCO he had 30 years experience with a major...as an accountant. Had the test all screwed up: increased the choke size, had the flare double in length and then calculated a lower flow rate then the smaller choke. Even my owners wife knew he screwed up. And measured the condensate yield 4X actually because he was entering 15 minute incremental tests when his software was calculating on a one hour cycle. Even worse: he knew what was happening but didn't know how the change the program so he knowling reported 4X the actual yield.

I really am getting too old to but up with cr*p like that. LOL

Tropical Storm/Hurricane Don caused 56 rigs to shut down this week, and it was relatively mild.

Why was anyone basing decisions on resource allocation in 1953 using the range of cannon as a benchmark? It brings to mind the notion of standard gauge railway being based on the spacing of Roman chariot wheels, which seems to be apocryphal, btw. Railroad Gauge and a horse's ass.

Back to the 3 mile rule, the story here is quite intriguing; I found this pdf which is an argument against, mostly in regards to extraction of hydrocarbons of course (what else is there to be had out there that even begins to approach oil/gas in monetary value?): Is This Holistic Ecology or Just Muddling Through? The Theory and Practice of Marine Policy.

Yes it is apocryphal. The standard wheel gauge goes back long before the Romans and seems to originate with the people (I don't think we have a name for them) who domesticated the horse and invented the chariot.

Horses interred with chariots

In subsequent ages they tightened up chariot wheel standards and by Greek times they were within a few centimetres of the 1.435 m standard that railroads use today. I could go on to talk about the ancient railroads of Greece, but if you are interested you can Google that yourself.

The origin of the three-mile nautical limit is well documented, it dates back to the 1700s.

Three-mile limit

Of course, why the US still uses this for resource allocation since the international standard is now 12 nautical miles (20 km) - about the range of most modern naval guns - is another question. For resource allocation, the international standard is 200 miles (300 km), and that can be extended if the continental shelf extends farther than that.

Oh, there shouldn't be any great mystery. It's a matter of money and power. The Feds aren't going to cede anything at all to the states that they don't have to. If that means adhering to something with antecedents that now seem silly, well, so be it.

Paul - Trivia: the state/fed boundary along the central La. shore line has an odd bow shape. Long ago Gov. Long granted Texaco (?) all the mineral rights from the shoreline all the way to the Mexican border. Not sure but I think it took a Supreme Cour decision to settle the matter. I've been told that bulge represented a settlement between the feds and La. Given the difficulty of defining a shoreline along a swampy coast. I think "tidelands" issues were a legal battle into the 50's.

NOAA has predicted an 'above-normal' hurricane season every year since 2005. Even if there are 6 category 5 hurricanes, there is no certainty that any of them will even enter the gulf, they could all go up the Atlantic coast, like in 2006. Since 2005, there have been four actual hurricanes in the oil producing areas of the Gulf, and four tropical storms.

The seriousness of hurricanes and their affects on oil production is vastly overstated every year.

""NOAA has predicted an 'above-normal' hurricane season every year since 2005. Even if there are 6 category 5 hurricanes, there is no certainty that any of them will even enter the gulf, they could all go up the Atlantic coast, like in 2006. Since 2005, there have been four actual hurricanes in the oil producing areas of the Gulf, and four tropical storms.""

And is that due to the TOP SECRET installation of H.A.A.R.P. in South Florida??

The Martian.

TheDave

It's hard to know what you would consider a "serious" impact on oil production.

But we can go and look at the EIA production data for the Gulf of Mexico, and, if you take 2003 as a baseline, assess the impacts for the 2004-08 time period ( 2004, 2005 and 2008 all had significant hurricane impacts in the GoM ). This tells you that, if we ignore the potential for increasing production over that period, nearly 1/2 a billion barrels of production was lost - that's a cool 100 million barrels of oil per year, or, in total the equivalent of some 90 days of US crude output. So, yeah, a flesh wound.