Lucky Economists, Unlucky Scientists?

Posted by David Murphy on January 14, 2011 - 10:55am

For decades, economists (Cornucopians or optimists) have been at odds with natural scientists (Malthusians or pessimists) when it comes to the scarcity of natural resources. The economist’s argument, summarized here by Julian Simon, is as follows:

More people, and increased income, cause resources to become more scarce in the short run. Heightened scarcity causes prices to rise. The higher prices present opportunity, and prompt inventors and entrepreneurs to search for solutions. Many fail in the search, at cost to themselves. But in a free society, solutions are eventually found. And in the long run the new developments leave us better off than if the problems had not arisen. That is, prices eventually become lower than before the increased scarcity occurred. (Simon 1996)

The viewpoint of natural scientists seems to be a bit simpler; the more scarce something is the higher the price, leading to increasing prices as resources deplete over time. These opposing views have led to some famous wagers in the past. The most famous occurred in 1980 between economist Julian Simon and natural scientist Paul Ehrlich. The wager was whether the price of five metals would increase in ten years time. Simon won the bet. Another bet was made more recently. In 2005, John Tierney of the New York Times wagered with Matt Simmons over the price of oil. Simmons bet $5,000 that the price of oil would be $200 per barrel in 2010. Tierney won the bet.

As a result, Tierney has publicly applauded himself and the economists’ view in a recent article in the New York Times. He states: “Maybe something unexpected will change these happy trends, but for now I’d say that Julian Simon’s advice remains as good as ever. You can always make news with doomsday predictions, but you can usually make money betting against them.”

But what is the real message (if any) to be gleaned from these bets? Is it that economists are always right and natural scientists always wrong? Is it that prices decline for commodities over time?

I argue that there is very little (if anything) to be learned from these bets, and I explain why below the fold.

First, as Paul Kedrosky and Dave Summers have indicated in their articles, the outcome of the Simon-Ehrlich wager depends almost entirely on the date in which the wager termed, not scarcity or technology or anything meaningful like that.

Let's examine oil prices as an example. Let’s say that I wagered in 1864, when the price of oil was $110 per barrel (2009$), that the price of oil will decrease over time. I would have been correct regardless of whether the wager termed in 1865 after one or in 1964 after one hundred years. However, if I bet in 1892 when the price of oil was $13 per barrel, that oil prices will increase in the future, I would have been correct in every year henceforth except 1931, 1933, 1945, and from 1963-1973. Neither of these bets would have indicated anything about the scarcity of oil.

Knowing this, how could anyone claim that either Simon or Ehrlich was correct? Simon was lucky, Ehrlich unlucky. The point is that scarcity is only one of many factors that can influence prices.

In fact, Ehrlich and Simmons both made the same mistake—they assumed that all other variables that effect price, such as demand, would either be held constant or only help their bets. But this was clearly not the case. In the fall of 2008 after the global economy imploded, oil demand declined all over the globe, and the price of oil fell accordingly from a peak of over $140 per barrel to just over $30. Energy prices are another influential factor. It is easy to counteract the effects of depletion (e.g. declining ore grade) by applying more energy (i.e. effort) in extraction, and as long as energy prices are low, this will not have a large impact on the cost of production. But as oil itself depletes and becomes more expensive, applying more energy in extraction to counteract the effects of depletion becomes less tenable.

Clearly, Ehrlich and Simmons made bad bets and lost, but Simon and Tierney made bad bets as well, they just happened to win. As a result, I would caution against believing Tierney’s optimism. He writes:

“It’s true that the real price of oil is slightly higher now than it was in 2005, and it’s always possible that oil prices will spike again in the future. But the overall energy situation today looks a lot like a Cornucopian feast, as my colleagues Matt Wald and Cliff Krauss have recently reported. Giant new oil fields have been discovered off the coasts of Africa and Brazil. The new oil sands projects in Canada now supply more oil to the United States than Saudi Arabia does. Oil production in the United States increased last year, and the Department of Energy projects further increases over the next two decades.”

But is this really reason for optimism? This is how I read the previous paragraph: 1) the future of our oil supply resides 30,000 feet below the ocean surface, requiring more deep sea drilling exactly like that that led to the tragic accident on Deepwater Horizon, 2) we have substituted our oil imports from Saudi Arabia where oil production is roughly $10 per barrel, to Alberta where production costs are upwards of $80 per barrel, not to mention increased greenhouse gas emissions, and 3) oil production in the U.S. is still roughly 1.5 billion barrels per year (4 mbpd) below the peak level in 1970, and the U.S. still imports most of its oil.

The bets made by Ehrlich and Simon as well as Simmons and Tierney were faulty because they assumed ceteris paribus conditions; that all other conditions aside from the one on which the bet is made (depletion in these cases) will not influence prices. In the real world, however, there are a number of factors that influence price. As a result, it is incorrect for Tierney to claim that his victory, or that of Simon, is a validation of the economists’ viewpoint on the price of commodities. The economists were lucky, and the scientists unlucky.

In other words, what did Tierney think about his prospects winning the bet in the Summer of 2008 when the price of oil went up to USD 140?

The wager was about the average oil price at the end of 2010, for 2010 only.

And despite the spike in july 2008 the average oil price 2008 was slightly below $100.

These particular bets don't, of course, show anything.

But I think we have to conclude that sometimes economists do have some insights into one very narrow part of the picture: price.

As the quip goes for cynics as well as economists, they know "the price of everything and the value of nothing."

Most here overlooked or underestimated the power of 'demand destruction' on price.

Of course, for the dismal science, the price is the most important thing. The fact that 'demand destruction' meant that vast swaths of people could no longer afford even the reduced price, is less important.

Bah!

No, the scientists were unlucky and should have known better, any one who gambles can lose. As for the Economists, of the Julian Simon school, they are delusional, have no understanding of thermodynamics or the laws of nature in general and base their conclusions on magical thinking. They are no better than astrologers or voodoo priests studying goat entrails.

Source:Energetic Limits to Economic Growth

James H. Brown, William R. Burnside, Ana D. Davidson, John P. DeLong, William C. Dunn,

Marcus J. Hamilton, Norman Mercado-Silva, Jeffrey C. Nekola, Jordan G. Okie, William H.

Woodruff, and Wenyun Zuo

Note to Julian Simon type economists: The economy is a subsystem of the ecosystem. There are natural laws and limits that no amount of human ingenuity can outwit. Either we start living within our means or we are FUBAR!

"There are natural laws and limits that no amount of human ingenuity can outwit."

Whether or not said economist accepts 'natural laws and limits' has little bearing on their economic thinking. They know one thing: we humans are damn good at kicking the can, and we'll keep doing it until we can't. Once that happens, all bets are off anyway. The 'good' economists may not know much about physical limits, but they understand human nature and herd mentality pretty well.

Correct, which is precisely why those particular economists are more like astrologers and shamans than scientists.

Their theories and prognostications cease to work, once the system within which they operate comes up against physical limits. Basically they do not accept that any such limits actually exist and hence their entire world view is profoundly and fundamentally flawed. Their understanding of human nature is only pertinent in a world where resources are still abundant. They haven't considered how humans behave when they are faced with extreme scarcity because they argue that we as a species are now too smart. They are convinced that we will *ALWAYS* be able to find substitutes or better ways of producing what we need to sustain us. They are *WRONG*!

This is something that both DanBrown and westexas touch on down thread.

Have you heard about the recent experiment with cold fusion being undertaken by a pair of scientists at the University of Bologna in Italy. The pair claim to have reliably created large scale energy production from the fusion of hydrogen and nickel nuclei. The by-product of the nuclear reaction is ................you guessed it, copper.

All of our problems are solved by one neat little discovery. The economists were right after all ;-0.

Sorry, I could not resist that one.

This bet is just another example of how, in the words of another economist, John Maynard Keynes, "The market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent."

Thanks Bronx; I still love that quote!

energy vs. power.....

We are living within our means. There has been, and still is, a lot of available fossil fuel, and we are using it.

As time goes by, means change, and we will have to live within some new means.

Human society has essentially no ability to either predict the future or to modify its trajectory to achieve a longer-term optimum. So yes, we are mostly FUBAR in the long run.

No, Merrill we are no longer living within our means we are in ecological overshoot.

http://www.footprintnetwork.org/en/index.php/GFN/page/earth_overshoot_day/

While I think it is highly unlikely that we will achieve it I disagree that we have no ability to do so.

We are living beyond our means in the sense that the son inheiriting $1 million and that spends $100 K/annum is living beyond his means, since the son is dipping into inheirited assets and not limiting his spending to expected long term income of about $35 K/annum.

But there is no reason not to spend ecological capital now in order to improve the welfare and enjoyment of those currently living, even if that limits the prospects of future generations. In fact, not to do so would require a capacity for collective rational thought, planning, governance, and discipline that it completely beyond the human species as a whole.

The passengers will always move towards the higher part of the sinking ship, even when it might be better to get closer to the water, jump in, and swim for some flotsam or a nearby ship.

That bolded part is so sad and so true.

...well enough said, but I would rather think that if BAU means wasting the planet to provide feasts, fun and games until we hit the wall, because that the way it is, because the theory is we are basically yeast and can inevitably do nothing better, then I would nevertheless still prefer to attempt rational thought, planning, governance, and discipline.

As I am human (and apparently not yeast) perhaps that means the choice is one that humans can make, and worthwhile. Enough individuals abandoning the contemporary masturbathon may be able to make a difference?

The way that works out is usually as follows:

One family doesn't water their lawn, rarely washes the car, makes sure the diswasher and clothes washer have a full load, and generally conserves water. Another family waters their bright green lawn, washes the car weekly and generally makes no effort to conserve water.

When the water supply gets low, the state puts out an edict that all families are required to cut back on water usage by 25%.

You can always propose a scale whereby the effects of an individual are nullified; you can also propose a scale where they are effective. I would suggest you read Ostrom and the like for community-size efforts which have been successful in managing scarce resources. It can and has been done in many areas, and it has been effective.

If the trends of history hold through our period of "accelerated change" (as it might be called), those who preach individual powerlessness and the pointlessness of sustainable community efforts are likely to be replaced by those who practice individual responsibility and become a part of sustainable community efforts. Darwin rules, after all, in the long term.

No, Merril is not interested in sensible planning. He has said that such planning is impossible (in spite of reams of evidence to the contrary). The main impediment to such planning is exactly his ideology. He would rather see the whole world go completely to hell than to ever question his own narrow ideology.

"Rather" has nothing to do with formulating a rationale expectation about the future. It would be a symptom of wishful thinking.

dupe

You miss out :- The family that waters their home grown crops, during the water shortage, with used waste water get fined by the courts. This is UK policy. Note too that this can mean a criminal record that will prevent entry to the USA and will block the guilty party from visiting on business hence destroying that business.

NAOM

Easy-peasy -- build a gray-water drainfield under your garden. Out of sight, out of mind. Since it's gray water, no biggie about sanitation, you can use cheap PVC with holes drilled in it, if you bang it up by accident, just fix it, or even leave it busted. Once your plants grow roots down to the drain field, you're golden.

Yair...dr2chase. Have you ever done it mate? I didn't find it that easy and it didn't work that well exept for bananas.

Some of these things are okay in theory but it doesn't always work out in practice...not that we shouldn't continue to try them and reach our own conclusions. Just don't expect them all to be answers to the problem.

We did actually, but it was Florida soil, very sandy and permeable, might have made a difference. Grew watermelons for a while over our (sewage) drainfield, and after that, just grew grass, really insanely healthy, green grass. Seemed like easy as falling off a log. I guess not, in general.

Not that easy :( People were being caught by the water boards flying over, in a helicopter, and looking for green gardens. If your garden was green then you must be watering illegally - guilty.

NAOM

EDIT: It meant that you HAD to throw out perfectly good, usable water.

How ironic and ridiculous was THAT, using choppers, which presumably burned diesel, to fly around looking for folks who might have been using a few gallons of water to keep their gardens from withering during a drought. I guess they couldn't be bothered to send a few inspectors around the neighborhoods on foot.

That's one of the best (or worst) examples of how the availability of seemingly endless supplies of inexpensive oil has completely skewed the way we've done things over the past decades.

The idea that a municipality would choose - and could afford - to have its water supervisory board spend $$ on diesel fuel to hunt down water-using scofflaws from aerial flyovers is an idea that should have never made it out of the conference room. Instead, it'll just be yet another footnoted anecdote that will serve as an example to future generations who wonder how we squandered our petroleum resources on so many frivolous pursuits in the Age of Oil.

In the UK the water companies are completely separate from the municipalities.

NAOM

I agree with the notion that our civilisation has painted itself into a corner that, as a civilisation we will not likely find a way out of, and that it is now very likely beyond the capabilities of our species to do so.

However, I see it as a failure of our civilisation, because there have been populations of our species that have managed to live in relative balance with their environment very well for many thousands of years. Australian Aborigines come to mind. A hotly debated topic is that 20k years ago they may have played a role in the extinction of the Australian mega-fauna (http://www.abc.net.au/science/features/megafauna/), but otherwise perhaps their success could be taken as proof that our species can live in balance with the world.

As our civilisation wreaks a mass extinction event on the planet and hurtles itself towards its own destruction, I am not sure we could honestly call ourselves 'advanced'.

Good points. The Aborigines are particularly apt, since one has to imagine that they came to their sustainable lifestyle and world view after recoiling from the devastation they saw they were wreaking on their environment. We need a similar awakening, I would say, whether it is otherwise too late or not. This impossible hope is about the only one I have left.

you are both wrong, actually. first, civilization seems to have been born in peace rather than war, so there is that. second, sustainable societies do exist, and without centralized leadership. third, Steve Keen has developed a model demonstrating a steady state-ish economy can exist within the current basic structure. fourth, we have the means to draw down carbon with simple, effective, natural methods.

there are solutions. for now. time window won't be open forever.

I appreciate this point of a view because it is the realist one.

IMO true economists appreciate this more than scientists. However, the free market has to be allowed to operate, even if that means allowing large industries to fail and millions to go jobless and perhaps even some to starve.

This clearing out process is natural, evolutionary, and has allowed human development to proceed.

We simply cannot live in a world in which every last 7 billionth human and their dog is supported and gets everything forever, in which big banks get unlimited money forever. This is insanity.

On the other hand, I think most of the evidence points to a big, big crash to occur within the lifetime of our children or grandchildren. This is no longer esoteric, or something that can be debated. Our grandchildren will starve.

So it's natural but it's also devastating, and we won't be able to do anything about it, and whatever we do will make the problem worse.

"I appreciate this point of a view because it is the realist one."

Presumably by 'this point' you meant:

"But there is no reason not to spend ecological capital now in order to improve the welfare and enjoyment of those currently living, even if that limits the prospects of future generations. In fact, not to do so would require a capacity for collective rational thought, planning, governance, and discipline that it completely beyond the human species as a whole."

But, of course, this is total self fulfilling prophecy.

The free marketers wage hot and cold wars for decades on all planned economies, then turn around and say--see, humans can't plan.

The logic is totally pathetic and totally pervasive.

The total absence of morality in a statement that says basically "it is the best thing to totally screw our children out of a livable planet if it improves anyone's life now, even completely marginally' would be breathtaking to most societies.

That it passes here with silence or plaudits, points more to our share in that utter immorality than to our ability to think our way out of a paper bag.

The Montreal Accord, among many other examples, shows that:

"a capacity for collective rational thought, governance and discipline" to improve the

"prospects of future generations" is exactly

NOT

"completely beyond the human species as a whole,"

even though it limited the "welfare and enjoyment of [some of] those currently living."

It is indeed a grim irony that those whose fundamental philosophy is that it is a deep moral wrong to ever try to plan or control human economic activity are the ones who then turn around and point at the results of their own 'free market' political systems as proof that humans cannot plan or control their own economic activity.

But this is how they want to spin it, so that is how it will be spun--conveniently in such a way that removes any blame from their shameful ideology.

Even though conservatives have long claimed that responsibility is of central importance, but that never seems to apply to themselves.

I tend to agree, though, with Chomsky that the victory of a particularly rabid mutation of this toxic ideology in the last US election finally and utterly seals our doom--we, along with most complex life on the planet, will go extinct in the not too distant future (or at best, in Sir David King's prediction, be limited it enormously reduced numbers, to the Antarctic).

You seem to understand the situation, at least partly. And after all, this is a discussion about economics, the "dismal science".

You have put your finger on the problem. Staving off the dire effects of Peak Oil would require the government management of business activity. Most US politicians regard this as anathema. Others believe that the management of the nations economic affairs is one appropriate activity of government, but that it is generally to be done through fiscal, monetary, and other very high level means, such as funding basic research.

Since the "fall of communism" the triumphal view is that most countries now adopt the free market, democratic system similar to that of the US. Whether that is true or not, it is true that most are engaged in a global economic competition that requires rapid exploitation of resources and populations to stay ahead in the economic race. Most countries do not have the luxury of pursuing economically inefficient systems.

Secondarily, most of the world's religions have an eschatological viewpoint that envisions an end time. Some religions eagerly await the end of the world. Others are simply fatalistic.

I'm not pessimistic about the ability of scientists, economists, and historians to predict within some fairly wide error bars how the world and human society will evolve over the next few decades. What I'm pessimistic about is the ability of the world's political leaders to manage an economic transition to a sustainable human society of several billion people.

The Montreal Protocol and the limitations on refrigerants to protect the ozone layer were possible because there were other refrigerants that could be developed. Companies could actually make some money selling new, more expensive refrigeration systems. If the situation had been that people had to give up air conditioning, the Montreal Protocol would not have been agreed to.

There's a fundamental difference between giving up freon and giving up fossil fuels.

"I'd go ahead and pay my carbon taxes IF AND ONLY IF the developing world cut back emissions by the same percentage we do"

Obviously true, and a point I make constantly to people that think that one is exactly the same as the other. But would you admit that this is, in fact, a counter example to your earlier broad claim?

What I see is (especially neo-classical) economists jumping back and forth between advocating for a very particular (and very damaging) economic system, to saying--oh, we're just constructing academic models.

But, in sum, I am equally pessimistic about world leaders, especially after the last elections. But usually 'leaders' are just trying to see where the bulk of "followers" is going and then trying to get a bit in front of them. If, in our more-than-ever interconnected world, the great mass of 'followers' start going in a profoundly new direction--something perhaps like transition towns--eventually the 'leaders' will follow. But anything at this point is almost surely going to be far too little far too late.

I am not sure what's left to discuss, except perhaps, how each of us chooses to proceed (or not) given these (near) certainties.

The son should be able to expect a real long term rate of return significantly above 3.5%.

At an expected rate of return of say 5-6%, which is still fairly conservative, the son is only irrational if he expects to live longer than 12 or 13 years, or has no other assets or sources of income.

At 8%, a common assumption underlying US pension schemes but probably too high for purposes of this example, he could go over 14 years.

This is nitpicking and your point stands. But just wanted to play with the numbers a bit.

Your numbers are right for limited-time annuities.

I was using 3.5% as an estimate for an inflation-adjusted, perpetual annuity.

The GDP is not know to any certainty by anyone. I could change the GDP and change the graph which is what economist have done for years.

Which would make no difference to my main point which is that technological innovation will not continually allow us to grow the economy once we hit physical limits. And that sometimes there are no viable substitutes for the resources that we have come to depend on. This is about energy and energy flows. Lots of cheap energy you get growth. Cut off the energy, growth stops and the economy contracts.

But if that was the main point, and the graph doesn't really teach it, why bother with the graph?

Right. The example I'd like to give is: Can one afford to buy a (reasonably livable) house with merely $1000 assured income every month indefinitely? Sure, but only if one saved, budgeted and planned it well. Otherwise, it is highly unlikely that one would be able to obtain a loan towards the house, however assuring the $1000 income may be. Afterall, what would be one's priorities if all they had went into meeting basic needs? However, it is much easier to buy a house if one had $50000 assured income every month even for only 5 years.

Fossil fuels and its extremely compact and dense form is comparable to a huge pay check. Albeit, only for a limited period. Solar and other renewables' flows are like living on a $1000 assured income every month. Sure, it is possible to live. But not at this scale - both in complexity and volume. Basic needs, today, may be wired to work over this energy guzzling infrastructure, but this horror too shall pass.

Predicting prices over a longer term is silly because both the money and the oil take on different values as times change. Almost every assumption about prices can be challenged including basic supply/demand relationships. Oil deliveries can be constrained while Foreign Exchange swings can make the scarce oil cheaper in a particular currency.

No matter how hard you try, you cannot predict accurately which makes price predictions a matter of dumb luck. Accurately describing what is taking place during the present is difficult enough!

The thing to keep in mind is that high crude prices inevitably lead to lower crude prices. This demand- destruction cycle has repeated itself over and over. The lower prices indicate crude users cannot profit @ higher prices. The low prices do not mean a large increase in absolute supply. There is less crude available relative to constantly increasing world consumption, this is where Simon, Tierney and their apologists are wrong. There have been no discoveries anywhere in the last ten years that contain conventional petroleum in recoverable amounts comparable to Cantarell or Ghawar.

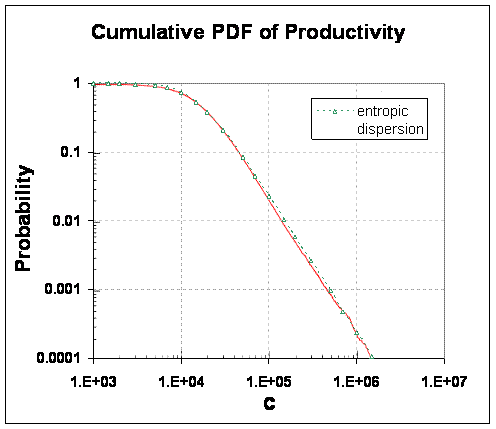

And that leaves us all with this problem: (click on chart for a sharper image)

According to that chart, across a broad range of energy values, GDP seems to vary by a factor of 100 for the same energy consumption. This suggests that the relationship between GDP and energy consumption is multicausational, not simply a naive power-law relationship between GDP and energy consumption. Alternatively, the GDP numbers might be highly suspect, or the energy numbers might be highly suspect, or some combination of all three. (The logarithmic scaling hides this to some extent by making a factor of, say, 10 look like a factor of not-very-much.) So the chart may teach us something, but possibly not nearly as much more than "goat entrails" as we might like?

I don't think that should be surprising and the authors specifically address that in the paper.(emphasis mine)

Are you saying you doubt there is a correlation between increased energy use and increased GDP? And yes, I do know that correlation is not causation. However from a purely biophysical perspective, you can not have an increase in growth without an increase in energy inputs.

Thanks for posting that graph Fred. We had a discussion here 3 days ago on whether you could assign a rough proportionality constant, K, to the relationship between energy and something akin to GDP.

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/7359/758178

The graph shows that it does exist (0.76 is splitting hairs) amongst a lot of disorder. And of course the disorder is perfectly acceptable if you account for it in a stochastic formulation, like you would by assuming dispersion.

No. The only reason energy consumption and GDP would not perfectly correlate is due to accounting differences. They are exactly the same thing. Money is only a medium of exchange. The thing that is being exchanged is only energy. We never paid anything for anything else other than energy. The thing we paid to get the energy is energy.

Oh yes the basic limits of physics aren't going anywhere, but... There is at least a factor of two difference between Japan's data and the US's (which is close to being on the fitted line). If we say Japan is near physical limits for kWh/GDP, the US could double it's GDP for the same energy consumption without hitting those limits.

The US could certainly make substantial improvements, but Japan does have some geographic advantages. Higher population density, greater prevalence of seaports, overall more moderate climate. I have argued in the past that the shape of their country (long and thin) contributes to overall transportation efficiency.

They've also outsourced some high-energy low-value parts of their economy. For example, Japan is a large net importer of food calories, where the US is a large net exporter. In 2008, roughly 15% of Japan's total consumed calories came from the US. If Japan were to attempt to be self-sufficient in food, they would have to expend large amounts of energy to make marginal land productive.

The real point that economists neglect is EROEI. As the high EROEI fossil fuels deplete we are going to enter a whole new ball game, and it is not far away.

Going from an average of 18:1 EROEI to 5:1 EROEI will be the game changer. Suddenly the tide is going to be very strong to swim against. The OECD countries will be badly impacted as producing nations continue to expand the consumption of their own oil at the expense of exports. Watch Saudi oil exports carefully. They have probably peaked.

You are correct that the timing of both bets was the factor. Resource depletion was not an influence - YET.

31/7/2010

Saudi Aramco's crude oil exports peaked in 2005

http://www.crudeoilpeak.com/?p=1738

Matt,

I know but they might just have some spare capacity, but I would not bet on it.

Matt Simmons had some Saudi production projections which were really low. I think that was the reason for his $200 bet. He also assumed that no one else would be able to replace Saudi production losses. But Russia and other FSU countries ramped up production:

13/8/2010

Saudi Arabia lost production share to Russia

http://www.crudeoilpeak.com/?p=1800

Correct again. But for how long can Russia keep this level of production. The only thing going for the Russians is that their population is not exploding like the ME.

What is the betting that Putin will be president again and then watch out. The oil tap will be turned off mighty quick if he feels like it.

Meanwhile the debt mountain of the west continues to balloon, robbing Peter to pay Paul. Our western socities have simply become too complex.

IMO it was pretty stupid of Simmons to have bet that oil prices would be $200. He should have taken the bet that Ehrlich took i.e. oil prices would be higher- after all isn't that the essence of economist view? Had he done so he would have won and then what would Tierney's argument have been?

Correct. Under the terms of the original Julian Simon bet, Tierney would have lost. And Mr. Tierney did not address the fact that annual global crude oil production has been at or below the 2005 rate for four years and for 2010 through October, despite the fact that annual oil prices have exceeded the $57 level that we saw in 2005 for five straight years, with four of the five years showing year over year increases in oil prices.

if the bet was on the accuracy of IEA production forecasts?

Ah yes, the Evil Empire of Economists. I know I can always count on some posters on The Oil Drum to give in to the madness of crowds that infects so much of the online world and broad brush all economists, including me by implication, as some sort of bizarro-world fool who can't understand something as simple as "finite". I've been running a site on energy and climate issues (The Cost of Energy -- get the double meaning?) for almost eight years now, and I've said for years that 2011 would be the year when peak oil really started to bite in terms of sustained higher oil prices. So I can say with 100% certainty that at least some economists do "get it".

Speaking of which, I notice that FMagyar got it right, and left the broad brush in the paint can. Thank you. I agree with what he/she said, especially about such bets. We see these all the time in the energy and climate change worlds, and I think they're stupid because they don't prove anything other than someone made a lucky guess, the Simon bet being just the latest example.

No, thank you Lou, and all other rational reality based people everywhere. We all need to give credit wherever it is due and stand up and shout loudly from the hilltops and point out the naked emperors and snake oil salesmen whenever and wherever we encounter them.

I would like to add my thanks to Lou for being resolute enough to go against the flow of his profession.

It seems to me that scientifically and technically trained people all too often have a tendency to religiously insist on adherence to the technically correct standards of evidence and experiment based reasoning, and refuse to allow a bit of ordinary common sense to play a part in their thinking.

The crowd is often wrong, but if only one kid is marching to the music, it behooves his parents to consider the slight possibility that the rest of the kids parents have instructed THEIR kids in that old saw about the hammer falling on the nail that sticks out .

This is otherwise often expressed as "the boss may not always be right, but he is always the boss"-if an economist wants to work, he must please the bau establishment with his public persona.

It can be expressed even more bluntly as "you must go along to get along".

I don't know any economists personally, but I would be willing to place a large bet that thousands of them do get it, and are arranging their own affairs in a prudent fashion-as well as giving appropriate advice in private to their friends and families and any long term clients smart enough to appreciate such advice.

In terms of human behavior, these observationally derived laws of folk wisdom are quite as helpful to understanding reality as Einstien's observation about the power of compound interest.

It's a pity most of the world is so ignorant of both the basic sciences and basic human nature that anybody should have to bother to point these things out.

But it does reinforce a point I keep trying to get across-our technically literate peers are all too often filled with contempt for those who are to in their opinions "driving(living) under the influence of alcohol(religion, bau economic theory, etc)"

Then they add a second generous measure of contempt of the unwashed because they refuse to accept on faith the new religion of science.The fact that science happens to be based on facts and free inquiry has nothing to do with it, insofar as the masses are concerned, because they know nothing about science, and never will.Hence they are being asked to exchange their old and comfortable world view, which has served them well(witness the fact that all of them are alive, that most of them are better off than at any time in the historical past, and many are VERY well off;there is another layer of irony buried here in the onion of reality of course, as science is due the credit but the bau camp gets that credit) for a new one-a scary proposition at best, and one likely to result in loss of social position, power, wealth, and professional prestige to many high ranking members of society as it is currently organized.

It does not surprise me in the least that even graduates of Ivy League law and business schools cling like leeches to the bau paradigm.Why should we expect Joe and Susy Sixpack to be any different?

I'm afraid I'm sometimes guilty of applying the broad brush. In any comments here critical of economist, please add "neo-classical" as a prefix.

We desperately need reality based economists, especially those who go beyond 'steady state' to give us some idea of what a powerdown economy might entail. Apologies to any such economists that waft across these pages if I have ever given any offense.

and I think they're stupid because they don't prove anything

Not at all, such bets prove ego clouded the judgement of at least one and probably both of the bettors, and that one got lucky.

Of course the market betting about the future is the biggest card game going so I guess we will keep getting more of these stupid high profile side bets.

I do know that when a bright professor I had during my last go round at a U proposed a stupid and tasteless bet about the fast approaching Gulf War her stock plummeted in my eyes.

moral of the story is never bet on price.

if the bet was on global C+C production maintaining a range rather than increasing production out of that range who would have won?

Price is a proxy measure, as price is apparently fixed to some other measure, which gives the definition of a proxy. The fact that price or money has to be inflation-adjusted (so to speak) over the years proves that it is tracking something else. So we need to figure out what money actually tracks -- Ehrlich and Simon should have bet on that instead of price. Seems kind of obvious in retrospect.

Inflation serves other purposes -- if you buy into the Keynesian view of the world, you need some inflation to give central banks some wiggle room to help kick us out of recessions. Paul Krugman had another example dealing with a (hypothetical? real?) baby-sitting co-op that suffered a market failure for lack of inflation; inflation is a way of persuading people to spend.

So it doesn't necessarily index anything.

The first part I agree with.

Yet, if it doesn't necessarily index anything, we are really at our wits end as to effectively understand it and thus to control it. I still think that it means something at any any moment, especially as a comparative measure; the difficult part is to extend that to work as an indicator over time. So you may in fact be right that it doesn't index anything, over an extended period of time.

"moral of the story is never bet on price."

uh, that is all you can bet on. The stock market bets on price. The real estate market bets on price. The commodities markets, the bond markets, all bet on price. So why am I stating the obvious? Because to dismiss the power of economics leaves nothing to bet on. Economics is a social science. If there are people, there is economics. This constant battle against the power of the money (the only thing you can bet with, other than your life or your freedom) is money, so the value of money is essentially everything. Go to your local coffee shop or your hooker and try to get what you want with a theory...forget, bring cash. (aside: I am embarrassed by how late in life I learned the above the hard way)

RC

:-) lol

seriously thou if i go down to ladbrooks i could wager on the C+C numbers in a IEA forecast... so who is being more theoretical?

My gripe with the economic argument is the assumption that all things have a direct replacement who's utilization is merely on the other side of entrepreneurial effort. Furthermore, they also operate on the assumption that pricing will remain more or less constant. While solutions might exist to lower prices, there's no guarantee that they'll be as low as they once were for a given commodity, or it's techno-fix, relative to other prices and incomes.

Markets are fundamentally reactive: all decisions of free agents within a market are based on a combination of perceived (subjective) value and relative wealth (inflation-adjusted income relative to past earnings, with debts figured as a negative value). If my relative wealth is eroded, as has been the case with the American middle class over the past few decades, and my debt load is high, again, as has been the case, then my willingness to invest some high risk next-big-thing will be low. My low relative wealth, and the perception that a safe investment is better than a risky one, that it is more valuable, will conspire against finding new solutions. Entrepreneurs require financial resources, they need investment. This investment won't materialize if purse strings are tight.

The assumption is that there will be both the resources and the willingness to pursue techno-fixes, but this may not be the case. Besides there being no guarantee that all things can be replaced, or that the replacement will be just as valuable as the commodity it replaced, there's no guarantee that society will have the entrepreneurial, financial, or technical wherewithal to find a timely solution.

I'll add that the reactive nature of markets lends itself to poor planning. Since the market relies on price signals, there's usually no incentive to undertake large investments unless there's certainty that prices will increase substantially and stay there, insuring a large infrastructural investment will turn a long-term profit. Commodity traders lend a certain element of prediction to markets, but they can also succumb to irrational exuberance over the value of a commodity (as in, I believe, the current price of gold) and create volatility in the market. Such volatility may actually serve to delay further needed investment, as investors and entrepreneurs may be wary of betting on a highly volatile commodity, until long-term trends show a general price increase.

It amazes me how many economists never read Smith's critiques of capitalism. In his case, he saw land as being the fundamental limiting factor; the ultimate irreplaceable commodity. His land argument still holds weight today, but now it's applicable to those other resources our modern economy requires to function: reasonably priced energy (an admittedly relative term), financial resources, and reasonably priced or replaceable commodities, such as metals or hydrocarbon feedstocks for chemicals, medicines, and so forth.

In short, solutions may exist, but there's no guarantee we'll find them in time, or that they'll be equally valuable to the commodities they replace.

There is also the question as to what degree that substitutes can offset the declines in conventional energy sources, i.e., will substitutes make an incremental or material difference?

For example, BP shows that Canadian net oil exports increased, because of rising tar sands production, by 339,000 bpd from 1999 to 2009. Over the same time frame, North Sea crude oil production fell by about 2.3 mbpd. In net export terms, Venezuelan net exports fell by 1.2 mbpd from 1998 to 2009. We would have basically needed four Canadas just to offset the observed decline in Venezuelan net oil exports.

And that's a really good point. Another issue with energy concerns is relative efficiencies as measured in terms of EROEI. I don't think I need to go into too much detail here, but the economic ramifications of spending ever-more BTUs to get BTUs are magnified to a degree greater than the EROEI ration as you factor in the necessary infrastructure investments. Oil sands are a great point: it's taking a lot of infrastructure investment to bring this resource on-line in terms of steam plants, mining equipment, natural gas lines, and pipelines to transport the synthetic crude to market. All of these costs must be factored into the total financial burden, driving up costs. In addition, the more infrastructure you have, the more maintenance, depreciation, and long-term loss of investment value, especially as you deplete that resource. Once the Athabasca sands are gone, none of that infrastructure can be reused in the same way that a traditional oil refinery can be upgraded or modified to handle different crudes (there are refineries here in Louisiana that have been in operation since the 1930s). If there are other resources, new investment will be required.

Conversely, we may be able to make up the efficiency loss in production by increasing efficiency in consumption, but now we're requiring investment on both ends of the equation, production and consumption, just to maintain a parity of relative value. The constant need to develop and deploy new, often times unproven, technologies creates further burden on society's financial resources. Look at hybrids: they've been on the market for over a decade, and still have yet to fall enough in prices to gain mass acceptance. Meanwhile, the stock of traditional fuels is ever-depleting and our solutions require ever more investments of finances and energy to unlock.

This has an affect of crowding out investment in more sustainable solutions. Case in point, it would make sense for the US to replace it's highway, air transportation and freight system with high-speed rails and electrified services. We know shared, electrified transit, with it's high efficiency and variety of fuel sources (lots of ways to make electrons flow) is the solution to our transportation fuels problem, but it would take trillions of dollars and decades to build. Meanwhile, I will argue that the need to development fuels that are compatible with the existing structure, albeit more costly than an electric transit alternative, for example, saps resources away from building a more permanent solution. It's always an infrastructural issue. Just because a solution exists doesn't mean you have the financial ability to bring it market and the market may not provide the most optimal long-term solution.

"Case in point, it would make sense for the US to replace it's highway, air transportation and freight system with high-speed rails and electrified services. We know shared, electrified transit, with it's high efficiency and variety of fuel sources (lots of ways to make electrons flow) is the solution to our transportation fuels problem, but it would take trillions of dollars and decades to build."

Some years ago, while working with a planner at GDOT, we were discussing all of the problems with MARTA (Metro Atlanta Rapid Transit). We were riding the HOV lane on an Atlanta interstate and I commented that the HOV lanes were barely utilized. I suggested that it may make more sense to retask these lanes to electrified buses. The lanes are along the center median, have their own entrances and exits, and adding overhead electrification could utilize existing infrastucture. We even discussed CNG/electric hybrid busses (a new concept at the time). His answer was that the funding structure to accomplish the change would be in direct conflict with the mandates of funding the interstate system. Retasking the infrastucture and money would be difficult under current law. Powerful lobbies would oppose any such plans and even proposing such a plan would open an expensive political can of worms. These are the limits the scientist/engineer/dreamer in me failed to recognize. We are deeply invested in the status quo, locked in it seems.

A neccessary first step would be the elimination of the many barriers to adapting and retasking existing infrastructure since building out all new infrastructure is clearly going to be too expensive; financially, environmentally and politically. Considering the results of the mid-term elections, the political will isn't there to accomplish these things, IMO.

Cliff, dead ahead.

TPTB, the ones most invested in the status quo, and hell bent on opposing any change, do so in large measure because most of them actually have swallowed, hook line and sinker, what the high priests of voodoo economics, such as Julian Simon have fed them. It's not just that they have vested interests and wish to stay in power, they truly seem to believe that what was, will always be, and that therefore there is no need to re-plot our current course.

First Mate: "Captain, "we have hit the iceberg!"

Captain: "...Not to worry, this ship is unsinkable! Full speed ahead!"

"End of the Ship" by Roy Zimmerman

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qNi1sevKNd0

Politics is invariably the Devil in the details. The established order will always seek to maintain it's privileged position in society, and thus will never adapt to change, regardless of how potentially catastrophic such change may be.

Fred,

I don't disagree with you however none of us, including politicians, have expertise in every conceivable area. So, we listen to "experts".

Suppose you are sick and "go to the doctor". He says, "Y'all gonna die!" Well, you naturally seek a second opinion. Are you going to ask someone who has a CV that reads like something out of reform school (but says he reads a lot) or are you going to go the doc with the long list of specialties and years of practice? He may have killed half his patients but he has the CV and "proven" expertise.

So, the politician, aside from being beholden to his financial backers, looks to those who are recognized as "experts" and it doesn't matter whether they really are experts so long as a bunch of other "experts" say so and they get on TV. Seriously, do you think any of them would listen to Fred and Todd on what to do? My guess is that they would be better off listening to us; but that's never going to happen.

I've reached the point where I recognize that nothing is going to be done to "solve" any of the multitude of problems we face. I find this sad but I'm not going to waste my time fighting their reality. I say "their reality" because I have the choice of sticking my head in the sand and believing or moving along with my life. I don't remember seeing this posted but people should take a look at http://www.declineoftheempire.com/2011/01/thinking-outside-the-box.html

Todd

In other words you have given up. So have I.

Though I remain pessimistic that TPTB will ever talk publicly about compounding growth / finite resources, I remain hopeful that "communities" will adapt and survive pretty well (for the most part).

We Aussies are a fairly laid back (apathetic?) kind of people, but when the chips are down, the community spirit explodes to the surface. Our most recent floods in Queensland / fires in Victoria show this.

Regards, Matt B

Hi Matt/Joe - I am an Aussie too - our politicians are both individually and collectively too stupid to recognise what is happening. Added to that none of them have any charisma and there is an absolute dearth of leadership ability. Only one commentator in all the hours of TV devoted to the floods has mentioned AGW, when clearly the highest temperatures on record in all of the seas (West Indian Ocean, Timor and Coral Seas) north of Australia must have at least had some role to play. There is great community spirit here, it will no doubt be sorely tested as unemployment begins to climb.

Amen.

So I am seeking the largest circle of real-world friends that I can manage, to do what amounts to "chopping up the lounge furniture of the Titanic to make life-rafts". If the image suggests something a little desperate and not likely to work really smoothly--I think that, too.

(Don't do it in the main ballroom: They will definitely try to stop you.)

So I am thinking about food, thinking about water, organic gardening for starters (finished my fourth season with encouraging success)--and noticing that time really is running out. Most people do not wish to lift a single finger to save their own lives. I am not optimistic about them at all.

Thanks for your link. Very good.

@Todd:

Todd, I don't think it is necessary to have expertise in every conceivable area. What leaders need is deep knowledge of systems science so that they know how to incorporate the specific knowledge supplied by experts. Sufficient knowledge of systems science, which, by the way includes a healthy dose of human nature, gives a leader the ability to know what specific knowledge is needed and often who really is the expert.

A great example of this is how Obama hasn't a clue about biophysical economics (or, seemingly any systems thinking) so hires advisers who were actually complicit in causing the financial crisis, at least creating the bubble that caused the rapidity of the crisis. Had he had any basic knowledge at all he would have turned to people like Herman Daly or Robert Costanza for advice on the economy.

But, while it might be feasible for a leader to do this, the real problem is that no one who would be competent will ever be elected as the leader. The reason is simple. The people don't want the reality, they want someone who will tell them things will be fine.

Question Everything

George

Systems thinking, yes.

But, as your byline suggest, people need to be willing to examine and question many of their own presuppositions.

Chomsky once said that simple honesty is needed more than great intelligence.

Unfortunately, of all resources, and even though it should be one resource that is infinitely renewable, honesty seems to be in extremely short supply (except occasionally here and at a few other sites).

"Economic geology" = word salad.

What flavor of economics are we today?

You enter the casino at your own risk......

Which brings me to this, which needs a punch line:

"A Geologist walks into a casino...."

(and walks out with all the... )

A geologist walks into a casino and they ask him what are the odds of a coin toss being heads. Simple he says: somewhere between 30% and 70%...probably

It's hard to find fault with that, though I guess it shouldn't be taken for granite...

I am trying to make geology more quantitative and if that includes the concepts of probability, that is OK. I finished a post last week describing the probability distribution of terrain slopes across the USA.

Get a load of this. I can from first principles of thermodynamics give the best probability-based estimate that you will land on a 100 meter square of a given slope if you treated the USA map like a dart-board.

http://mobjectivist.blogspot.com/2010/12/terrain-slopes.html

Many people may not find this interesting or intriguing, yet this same distribution occurs in long-term stock return on investment, a "slope" function in its own right. What will become apparent in the future is that what we are trying to control is garden-variety entropy that doesn't take a genius to figure out. All the actors are filling up the available state space, which leads to the characteristic definition of entropy.

BTW, geophysicists have been trying to find the general terrain distribution for some time. Curious if ReserveGrowthRulz will get upset again.

Sorry, no puns.

Oh no?...

Good work WHT!

Now can you can provide a possible explanation for the relationship?

The explanation is a two-parter.

The first part has to do with energy and how likely high-energy structures will occur. A steep slope or grade is a high-energy structure, and more of the earth's forces were required to generate steep slopes (or more erosion for valleys as well).

The best model of energy distribution is a Boltzmann or Maximum Entropy distribution where the likelihood goes as exp(-S/U), where S is the slope and U is an energy scaling factor within an area.

If you only take this it works reasonably well for certain pockets of topography across the USA, but not the entire area. So what you need to do is create a distribution for U across the entire meta-region, say the USA. When you do the averaging, again using maximum entropy to smear U out, you get what is called a BesselK distribution. This is a bit of a bizarre function and is obscure enough that it explains why no one ever developed a model for terrain slope distribution.

So the general idea is that two levels of entropic dispersion get applied and that is the outcome. A deeper explanation is on the blog.

so your point is it's a deterministic universe after all ?- )

This actually IS true. But it seems to me very dangerous to stake the entire future on what MIGHT happen. A few decades may have suggested repeated substitution as a way to overcome limitations, but there is absolutely no guarantee that this trend will continue. Repeated substitution has its limits TOO: eventually, there will be nothing left to substitute with, because all alternatives will have been thoroughly exhausted.

Furthermore, there are many records of primitive tribes who have exhausted their resources, such as wood and wildlife, but because they had no advanced knowledge of physics or the properties of materials, they couldn't possibly be expected to make AN IMMEDIATE transition from say wood to petroleum, or wildlife to advanced high-yield agriculture, and so they perished. They perished because their knowledge did not advance as fast as they were burning all their bridges. This is what will soon happen: Man will bump against the limits to his conceptual knowledge of the physical world.

I state the problem thus: Humankind will alleviate the coming bottleneck if it manages to do the following:

1. Find a way to transmute metals from other baser types of raw materials eg Gold from Copper, or Indium from Silver. In so doing man will be forever independent of anything which occurs naturally, sparsely, randomly and in scarcity.

2. Discover what energy actually IS, so that it too can be manufactured, in unlimited quantities and with as high a density and rate of discharge as man could wish.

3. Manufacture and consume only synthetic foods, and do away with fish, livestock, and anything else occurring naturally, so that man need not rely on the low replenishment rate in the natural world.

These are tremendous feats to accomplish, and they no doubt imply such an expansion to conceptual knowledge as is far outside the reach of the mind of man at the current moment in time. Engineers, doctors and lawyers may be churned out in batches, but no such thing is possible with the highest order of genius such as Einstein or Newton. MAN ONLY EVER STUMBLES INTO THE FUNDAMENTAL LAWS OF PHYSICS BY ACCIDENT, AND THAT TOO EVERY FEW DECADES OR CENTURIES. HE DOES NOT PRODUCE THEM ON SHORT ORDER AND UNDER THE STIMULUS OF MARKET FORCES. (Let us remember that many generations of naturalists, philosophers and scientists, including Newton, once spent many futile centuries trying to discover alchemy: how to make gold out of lead.) But even if, by some spectacular miracle, all the above 3 challenged can be accomplished, it means the population will further explode to 10 billion, 20 billion, 30, 40. If the individual is already devalued, alienated and fragmented in a world of 7 billion, I wonder what will happen in a world of tens of billions.

And thus it is NOT true. It is only true most of the time and that is what makes it such a dangerously deceptive ideology. You'll be completely correct 98% of the time . . . until you hit an exception.

But the good news for the exceptions is that at least you hit them gradually and with some warning . . . the prices of the resource will begin climb that cannot be stopped. If you are wise enough to recognize this situation when it occurs then you can make alternate plans. But our problem right now is that people are still in denial about it occurring.

This is the leap of faith Simon asks us to take. This is a statement of religion, not science. And natural scientists and engineers have every reason to be skeptical. For a simple example: There was an attempt to convert from scarce copper wire to aluminum. After many homes burned down cities realized that was not a simple substitution and now it is illegal.

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/19/realestate/19home.html

Oil, refined into fuel, has such wonderful properties (high energy density, liquid, low toxicity, etc) that trying to substitute any competitors will be very difficult.

Check out this graph of fuels:

from Energy Transitions Past and Future

Just trace for a moment the human economic history: Energy density of wood replaced by coal. Energy density of coal replaced by diesel. Now trace down to the energy density of batteries. 200 years of transportation innovation largely undone. Thus we reach the end of jumbo jet air craft and high speed cargo freighters.

George already did a great job of talking about EROeI in his post. Our society has tried, but not yet produced energy sources that are lower in cost than fossil fuels. And the net energy of our energy sources determines the size, growth rate, and complexity of our society. Yet among many, the faith continues. Any day now, an energy source will be invented that is better than anything that has gone before. Any day now....

The faith proves... false.

Right, but: what has the greatest need for compact, dense, fuel? Very much, vehicles. Our cars, in particular our very large single-occupancy American cars, are not essential. We could make them far smaller and lighter -- we could obtain "safety" by making the cars themselves "smarter" -- or we could simply choose to get around most of the time on scooters, e-bikes, or bikes. Or maybe, the smart cars will be publicly owned, and behave like robotically dispatched minibusses, so that everyone is de facto carpooling from door to door. There's probably more innovation possible on the consumption side than on the use side, partly because fossil fuels have been so cheap for so long.

There will be vehicles that do require high-quality liquid fuel, and they'll get it, at a high price.

People, especially in the US, are convinced that cars are necessary for the vast majority of transportation, and that is simply not true. They'll piss and moan when gasoline this $10 or $20 per gallon, but pissing and moaning is not the end of civilization.

ah, but the point that many here on TOD have brought up again and again - is what will all the people whose jobs rely on dense, high-quality fuel, do for a living? On the downslope of the fossil fuel era (outside some Deus ex machinca like solving the overwhelming engineering problems with fusion), there are an awful lot of people doing jobs that are going to go away - most likely for ever. Our present economic system (esp in the US), is just not prepared to keep "unproductive" members of society alive for not building cars, insuring them, fixing them, working on the roads the cars drive on, drive-through windows etc etc. - I just don't see a US with everybody walking to work having enough jobs to keep everybody busy and alive....

The missing link: Energy Transitions Past and Future

In the US most buildings are sited such that private autos and tractor trailer trucks are necessary. Very few suburbs or shopping malls are viable if mass transit is the only option. The average car travels more than 10k miles per year in the US (27 miles per day) and that kind of energy and time expenditure won't be possible.

The only other option is to rebuild to a walkable landuse pattern. That will be tremendously expensive and very destructive to the current built infrastructure. The US will go through a land use change that will be similar to Europe reconstructing from the WWII bombings, and yet will have to cope with a shrinking resource base.

I am not arguing civilization will end. But I think if the average US citizen maintains even a 1930's standard of living (low wages, long hours, poor living conditions, walking or train transit), it will be a remarkable achievement. I think there will be a long period where a large percentage of the population is living in temporary housing. Where people are jammed India style on trucks (no time to build the number of busses needed to replace cars), etc. Bankrupt governments and roads with potholes large enough to swallow a scooter. Gated communities and oppressive security to keep safe the 10% remaining "wealthy".

And I think my point is that saying "only option" is a mistake, and I also think that your "most buildings" assertion is a mistake, or nearly so. I think it is a common US mistake to focus on size, instead of actual count. So we have large areas of the country with buildings that would be expensive to access -- but NYC (and other dense cities) have a whole lot of buildings in them. I don't know the proportion, but I am familiar with the size-vs-count mistake.

If I imagine how things might change, I would expect -- better utilization and maintenance of rail lines (given improved technology, both for inspection and scheduling), containerized cargo for long-haul transit. Barges too. Trucks for short haul. Trucks are probably some combo of E or hybrid -- there's a haul distance and unloading dwell time where this begins to make sense. Trucks could be overhead-electrified, like "trackless trolleys" in SF and Boston.

I would expect bicycles, electric assist bicycles, shelled bicycles (look what happens when you give people a safe smooth place to ride bikes), and electric scooters.

One thing I would definitely not expect is the sort of one-size-fits-all use of one vehicle type that we have now. That's what gasoline allows. The huge advantage of bicycles is that little is impossible, instead it is merely (very) inconvenient. A long-haul bike (e.g, a Mango, see link above, plus electric assist) might be cumbersome in an urban area. An urban-friendly bike (small, light, easy to haul up stairs) might be a little slow and tiring for a 40-mile ride. A folder won't carry much cargo, but will fit conveniently on a train or bus. Cargo bikes are wonderful, but don't fit in all elevators, or easily on the front of a bus. (and that's just diversity in the world of bikes, never mind scooters, robot bus-cars, or whatever else we come up with).

I don't want to say that bikes are the "only option" -- I natter on about them, because I ride one often, and I know from personal experience that what many people claim is "impossible", a 50-year-old fat man does all the time. But if we're overlooking a technically feasible option that is right in front of our faces, who knows what we'd find if we actually went looking? And again -- the point that there's a huge opportunity on the demand side.

I think MacDuff is more nearly right, and that is the cause of some of our overlooking. Whatever more-efficient choice we make, is likely to leave some of the current economy high and dry. Don't expect GM to develop products that would put GM out of business. Bikes are worst-case for this -- they reduce auto and oil consumption, but they should also have a non-trivial effect on the demand for weight loss products, gyms, and several chronic-condition medications (that much exercise makes a real difference). Big Pharma would not be happy to see a 15% cut in diabetes or cholesterol meds. On the other hand, bikes need maintenance, and the beer industry ought to do well. I wear a lot more wool nowadays, too (good in the cold, even if you get sweaty, doesn't stink much).

Bikes are great. But they are not so hot in the snow and in the rain. So you need some type of fall-back whether it be car, bus, train, telecommute, etc.

I think the US will just migrate from big cars & SUVs to Euro style smaller cars, hybrids, and EVs. The big cars & trucks are very wasteful . . . we could cut a LOT of oil use out by just switching from big cars & SUVs to small cars, hybrids, and EVs. The exact same A to B individual enclosed transport is achieved but with gasoline savings from 20% to 100%. Yeah, EVs have range issues and are expensive. But when push comes to shove, Joe Six pack is far more likely to trade in his SUV for a Nissan Leaf than for a bicycle.

But again, Bikes are great. I biked to a previous job a lot. I currently work at home. And our Secretary of Energy, Dr. Steven Chu, is a HUGE fan of bikes.

I bike all year around here in Norway. Ive never had a day here where it was so much snow that it was impossible to get to work. The thing that stops a bike is slightly compacted/transformed snow a few inches thick. With studded tires ice is not a big problem.

Last winter i used my car mostly to charge its batteries and see if it was still working, and i sold it in August last year. What a blessing.

And if its so much snow that its impossibel to get anywhere in a timely fashion with the bike, you can use crosscountry ski's. Old, proven technology that predates fossil fueles. It beats walking in deep snow.

I am doing the biking in snow thing as well, but not so much this month because its been a bit less convenient. Now the question is how do you transport the XC skis on bike? I always end up taking the car to get to the trails.

My answer is probably kinda expensive for you, but it is canned, and an option for me, because I spent the money, and I have not regretted it at all. Get an XtraCycle FreeRadical or a Surly Big Dummy.

Here's a picture of a guy carrying pole-vault poles:

http://www.xtracyclegallery.com/2010/08/516-vaultbrad-xtracycle.html

And this guy, who probably has the most embarrassed daughter on the planet:

http://www.xtracyclegallery.com/2010/05/485-larry-xtracycle.html

And many more. This is the bike you get, if you don't want to be the guy who says, "I can't..."

This is one potential low-oil future. It doesn't suck.

I only need to walk about 5 minutes to get to the trails, so ive never had any need to transport my XC skis on a bike.

My commuter bike right now is just a old MTB, and when i need to transport something i use a 85 liter backback. Its not the best solution, so now im building a Big Dummy cargo bike.

http://surlybikes.com/bikes/big_dummy_complete/

Both you guys think alike, and they look like workable solutions. Whenever I am riding I think of minimizing my cross-section and trying to keep as small a target as possible to motorists. I can't get over that hump of carrying something large around.

Man, we're way off topic, but I'd love to evangelize. (You've been warned now...) I can offer several suggestions that seem to help. Number one, you want to be visible, not so tiny a target that they don't see you (that said, I excel at putting my giant bike into tiny places -- it has special skinny handlebars, no wider than my hips). Number two, that huge bike, seems to get your more attention, and more room, than a "normal" bike. Number three, you know how there's cars and motorcycles with headlights-on-always? Same for my bike, off a dynamo hub. (Sadly, this is also expensive, unless you are handy with a soldering iron). This really helps. Oh yeah, fat slick tires. Immunizes you against all sorts of road hazards, lower rolling resistance (I measured, the video of the experiment is on the web), less vulnerable to puncture, slower to go flat, comfier.

And yeah, I know that this is a hard sell for adults who didn't get comfy in traffic when they were young and stupid. I used to be an effective cyclist, I gave it up, because it doesn't work for anybody else I know. We should copy the Dutch, wherever we are demographically/topographically like them.

The big bike is almost bizarrely stable, or else I've become bizarrely stable. I've clipped immovable objects with cargo or the cargo frame a couple of time, and the bike just hops to the side and keeps on going. I can balance it at a walking speed on rumpled snow-ice junk while chatting with a friend. It's tough as hell, I've gone off curbs with three kids riding on the back (a Big Dummy prototype traveled from Anchorage to Tierra Del Fuego, so did an xtracycle).

Load limit is 200lbs cargo (I have carried this). Wiggly (human) cargo is a little harder, till it learns not to wiggle. 100lbs cargo is comfortable, and I have often carried 100lbs of live (daughter) cargo uphill. 50lbs cargo, I'm still riding no-hands (except snow tires are squirrelly and I cannot get comfy no-hands). For serious hills, there is an electric assist specially designed for these cargo bikes (StokeMonkey, feeds through the gearing), people have hauled 200lbs cargo up 30% grades in SF).

Other big-bike advantages include: you can fix it with hand tools, by the side of the road. If the road is impassable, you can hop off your bike, and push/carry/drag it around. If you are delivering a load, you can deliver it to a door. If you are delivering a kid to a soccer field, you can deliver the kid to the edge of the field. Parking, easy. Traffic jams, you filter through. Hauls bikes behind it, too, pretty easy.

I log about 50 miles/week, winters are tough to make it, but I try pretty hard. The health benefits are substantial, especially when you reach an age that you'd appreciate some substantial health benefits. For example, I made my knees sore snow-shoveling earlier this week, and I fixed them today biking (I've only been doing this trick for 25 years -- said the knee doc, "I can cut you open, or you can ride your bike....") I'm down 20 pounds from when I re-started riding. So you see, anyone driving, who never biked seriously, only thinks about the rain, and the snow, and how do I do this, and how do I do that, and they don't think, "my f**king car is making me fat, messing up my blood chemistry, and making my joints all achy". You look at all the crazy sh*t people buy in random attempts to get healthy, and you wonder, guys, do you listen to your doctors, EVER?

(And seriously, to most people, what's more important, peak oil and global warming, or losing 20lbs and de-aching all their tired bones?)

AND, I get to drink lots of beer. How cool is that?

To attempt to drag this vaguely back on topic -- we have more room to innovate on the consumption side, than we do on the production side. I own the "technology" to be a 3000 fossil-fuel-to-food-to-passenger-mpg vehicle. My bike is sitting outside. It's cold, I can cook a batch of oatmeal (ERoEI, 5:1 !) on my wood stove (we need the heat, hence heat to cook is not counted, ha-ha, otherwise 2000 pmpg). 3000 pmpg, today, I own all the technology. And ANYONE else with oatmeal and a bike can do the same. Can you say that about anything else on the production side? Not "we're researching" or "looks promising", but essentially already deployed, merely waiting for people to pick up free efficiency from the sidewalk. 3000 pmpg? How long till we can do that with "cars"?

Apologies for the rave/rant, but seriously, if we drove cars 80% less, I'd be just fine. And I think a lot of people would discover that it doesn't suck, once they tried it. And the oil, auto, pharma, and who knows what other industries, would lose a ton of business.

Hi dr2,

Sounds good.

re: "(I measured, the video of the experiment is on the web)"

Link?

I thought Google could find it pretty easily, but it takes a little digging.

Blog entry, explains protocol, links to video. Note the distinct lack of lab-safe footwear. Note also that these are thin tires, without much tread or lugs.

The reason people race with thin tires, is wind resistance, which increases with the square of the speed (and since the speed is linear in speed, the power requirements are cubic).

A sufficiently large and potentially car damaging object can cause drivers to give you a wide berth. It doesn't actually have to be dangerous to cars but to give the psychological effect. I am thinking about looking for a couple of rubber toy knives to fit in the ends of my handlebars ;)

NAOM

http://www.geekologie.com/2009/01/25/bike-key-1.jpg

Not nice, I prefer the psychowar approach. Scaring them into giving you space is better than revenge.

NAOM

Fun to think about, but not productive in the long term. If you want to get more people on bikes, people who aren't already on bikes need to perceive biking as something that normal, civilized, people do.

Besides, I'd probably just stab myself with the key by accident, and it makes my bike permanently wider than it needs to be.

And today, I am probably driving to work (roads narrowed by snowbanks, and cars take up the whole road, leaving nothing for me), so I will be Part of the Problem.

Trailers work well. I pull my 18-foot-long kayak to my local lake in a trailer I made myself from some wheels I found in the trash and a couple of 2x3s.

I was going to wait to see if someone else said something, and they did :-). I also ride a bike in the snow -- apparently if you try, it isn't nearly as impossible as it seems.