Tech Talk: The Earliest Longwall - Coal Mining before the 1830s

Posted by Heading Out on July 25, 2010 - 10:16am

Previous talks in this series can be found by clicking on tech talk, in the tags, or at the top of the "Home" screen.

Earlier I have written about the large amount of coal that was often left to hold the roof up while miners excavated the coal from rooms offset from main tunnels, with the rooms themselves being extended to create an intersecting set of passages. But even where the pillars left between the original tunnels are later removed as the mine retreats the working faces back towards the main shafts and exits, a significant amount of coal can be left.

About 250 years ago this was a clear problem in the Shropshire coalfields of the United Kingdom. At that time underground mining was usually carried out by crews of men and boys, where the coal was first removed by undercutting the coal seam manually with a pick, to a depth of about 3 ft. The bulk of the coal was then broken down to this slot and the fragments (ideally about 4-inches in size) were shoveled and hand-loaded into pit tubs, to be hauled away. A good day's work was about 20 tubs, and I have described this method and how it evolved, in earlier posts.

However, even as early as the 17th century (Economic Development of the Coal Industry 1800 – 1914 Brian R. Mitchell p 71), a different method of mining began. At first it was known as Shropshire mining because of where it started, but it later became known as “longwall mining”. The advantages, even then, of the technique were obvious. They included a greater percentage of larger coal (easier to sell), simplicity of working and ventilation, better roof control and a greater production of coal from the workforce, perhaps as much as 30% higher. In particular it was a cheaper method of mining and it allowed a much higher level of production from an area by concentrating the activities of the miners, and focusing the transport.

I just came across the book that appears to have been the first proposal for the more modern version of its use. (The Miners Guide – being a description and illustration of the principal mines of coal and ironstone in the counties of Stafford, Salop, Warrick and Durham”, by Thomas Smith 1836). And so I thought I would begin this short sequence on longwall mining with a description of how the technology first evolved, from that book.

The method was one that gradually evolved from initial headings that were mined by two separate working teams, the first being the holers and the second the brushers..

When the coal was of good quality, and high, then the process was to undercut the coal to a depth of 3-ft, with a man being able to undercut a length of about 22.5 ft a day. He would then cut vertical cuts to the same depth along the edge of the heading, which in the illustration below would be about 30 ft wide – depending on coal and roof quality. There were a group of these men who initially worked the face, and then moved on. They were followed by the brushers, whose job would be to break out the bulk of the coal from the face, and load it into tubs. They would also support the roof with timber props, as this was needed and the coal was removed. This was conventional room and pillar. But it left a lot of coal in the pillars.

Initially it was in thinner coal seams that “the long way” was developed as a way of getting almost all the coal out.

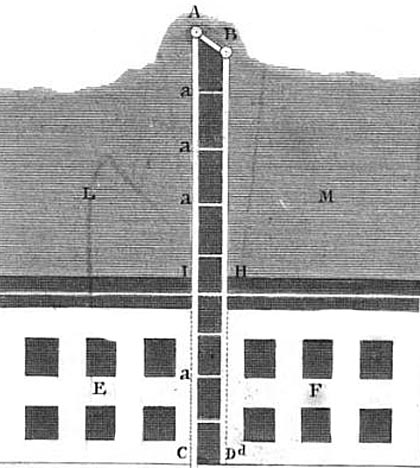

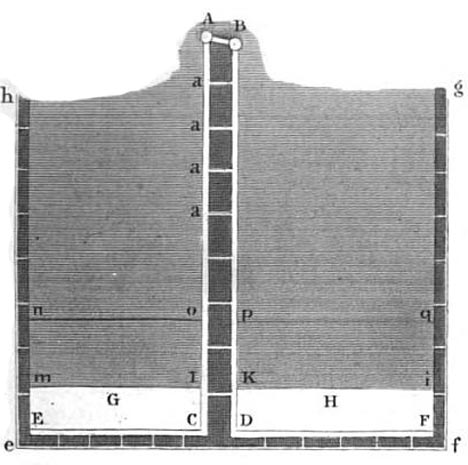

First, as with conventional mining, gate roads are dug out to the edge of the property (back in those days this was about 300 to 600 feet) with the direction going down the dip of the seam from the shafts at A and B, which are about 20 ft apart and some 7 ft in diameter. These roads were 6 - 9 ft wide and full seam height. Air passages or thirls were driven between the gate roads to help ventilate them as they were driven (the “a” passages). Cross-connecting tunnels between the gateroads were then driven, near the edge of the property.

In those days it cost around 0.35 to 0.4 English pounds (Ep) per yard, with workers being paid 0.225 Ep per day including candles and drink. The thirl would cost around 0.15 to 0.2 Ep per yard to drive. (An area up to 60-ft in diameter would be left unmined around the shaft area to hold it up).

Once the edge of the property had been reached then a section of the mine, some 90 ft long, would be mined with six miners each taking some 15 ft and holeing the coal. This was undercutting the face, to a depth of 3 ft, over each stint, and it would take a day, with the each miner also cutting a vertical slot at the edge of his section, so that it was held only by the coal at the back of the panel. The sections were mined on either side of the gate roads, moving towards the common middle of the “panels” being mined.

The holers were then finished in that section and moved to a different section, and a second set of miners mined out the rest of the coal, known as brushing the coal to the 3-ft depth. At the same time, since they were removing all the roof support they would put in timber props to hold the roof up, and would also construct small pillars or cogs, that were made from stone, fine coal, and other refuse, when they felt they were needed. In this way the white strip shown in the diagram below, at the back of the mine was extracted first, with the sections progressing first laterally out to the adjacent gate roads, and then back towards the shaft. While it takes 6 men to hole the 90 ft face, it would take only 3 men to brush and cog it. (And they would use small charges of gunpowder to help if the coal was not easily broken out). The difference from conventional room and pillar can be seen in the small size of the cog pillars that were left, as mining progressed. In this case, from one gate road to the next, with the mining face parallel to the gateroads and retreating from one to the next.

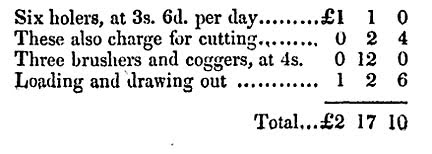

Wooden tracks were laid along the gate roads, and then bent to pass along behind the face, to allow a horse and boy to collect the tubs as they were loaded, and then to replenish the men with empties. The costs for this method of mining, which was known as broaching, was given as:

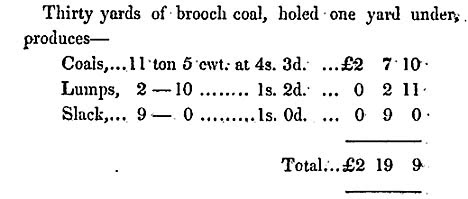

(note that there are 12 pennies (d) in a shilling (s) and 20 shillings to an English pound of the period. And an English pound is now worth roughly $1.50). At that time the market for coal was such, that the mine owner would expect to get the following for the coal (with the price based on size).

A profit, at best, of just under 0.10 Ep per day, per working section.

The technique was still quite dangerous, since the expanse of roof that the miners worked under got larger as the excavation moved away from the gate roads, and the cost of moving rock and dirt into the workings to build the cog pillars would have been significant (as would the time taken to assemble them).

Thus a new method was proposed, and the initial description is as follows:

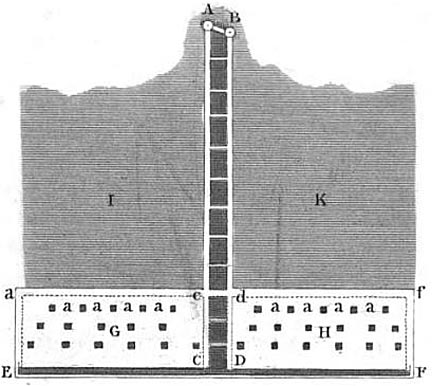

For getting out the coal by long work, the pits A and B are sunk, as in the other case, at a distance of six or seven yards from each other; and the main gate roads driven to the boundary of the work at C and D, properly thirled with the openings for temporary use. From the ends of the main gate roads branches are cut, at right angles, to E and F, along the boundary line of the proposed area to be cleared, so that the mine may be said to be headed in the form of a Roman T, the roads E C, and D, F presenting the faces of the coal, which are to be worked homewards, or towards the pits. Simultaneously with the traverse gate roads, an air head ef is driven at a distance of three or four yards, with its thirls, which are closed in succession as the work proceeds. . . . . .The necessary roads and heads being completed, the work of getting commences; in order to which, the miners hole one yard under along the entire faces of work EC and DF which may be each from 50 to 100 yards in length according to the extent of the area to be cleared. Cuttings are then made at proper distances, to the height of five or six feet, or to a convenient parting, and the coals are brought down, turned out and drawn away along the gate roads. Cogs or pillars are then constructed of the waste and slack, to support the upper measures.

The holeing and cutting then proceed another yard in width, and then another; still clearing away the coal and supporting the roof with cogs, till the lower measures are drawn out, to the width, along the under face of 8 or 10 yards. By this time the over-hanging measure have, by their gravitating force (sic), sunk and bedded themselves on the cogs, pressing them down to a sort of continuous floor of what is called gob, or compressed and compacted slack. This is assisted by the use, as experience may dictate, of timber, which is taken away when the working of the stage above commences.

This is the first description I have found for what we now call longwall mining. By turning the mining face so that it advanced into the solid and away from the opening left, the overlying roof was able to bridge over the working area. This considerably improved roof control, and made it a much safer method of mining. In presenting the method the author notes that the cost of large coal, using room and pillar mining, which is the top method described, worked out to be around 0.118 Ep per ton mined. When the costs were worked out for the long way, the mined cost was found to be 0.105 Ep per ton, giving 0.013 Ep (3.25d) benefit.

However the increase in the volume of coal produced (and thus the royalty yield per acre) doubled to 2,046 EP per acre.

At the time that the book was written, it was a method just beginning to be developed, and the presentation was as much a proposal as a description of something in place. How it turned into the most productive of underground mining methods, in the course of the following 180 years will take another post or two to describe.

HO: Thanks for the post! I do so appreciate the historical info in these tech talks on coal mining.

I lived in Scotland from 85 to 87. Heated the cottage with an open coal fireplace. Picked up the coal after shoveling and bagging it myself in hundred weight bags. Delivered it to the cottage and did all the work required to burn it. Really oldschool stuff. It was dirty work and dirty heat. I tried different methods of burning to get my effiency up. .... even burnt petroleum coke in mix with lesser grades of coal..... that burns real hot but will eat your grate. Many Scots during my stay would burn peat all day.... it would smoulder. But peat was cheap comparitively.... Back in the day..... life was different to say the least....

Regards TG80 sends

"Back in the day..... life was different to say the least...."

One thing I recall was having to have a coal/coke fire burning in the main living room to provide the hot water in the bathroom upstairs. My Dad used to collect the dust and fines from the coalbin floor, dampen it with water, and use it to tamp down the fire before bed. In the morning a good poke and some added coal got it going again. I don't miss anything there.

Thanks for the education, HO - never really knew what was involved in the mining.

Heading Out,

This is fascinating stuff.

What I wrestle with is what the wages of these wretched workers meant in today's terms.

There is an excellent UK Parliament report on the retail price index 'Inflation: The Value of a Pound: 1750-2005'

http://www.parliament.uk/documents/commons/lib/research/rp2006/rp06-009.pdf

This says that to get from 1830 pounds to 2005 pounds you need to multiply by a factor of about 75.

So if coal was being produced at £0.1/ton in 1830, that's equivalent to it being about £7.50/ton now.

Coal is now about £50/tonne. I presume that's in part because real wages have gone up.

If a holer got 3s 6d per day then, that would be equivalent in real terms to about £22/day or a bit over £2/hr.

Presumeably upstairs a noble lord was raking in the £2,000+ per acre royalty.

I don't understand this well enough to work out the details, but I am wondering if there really would be enough left over for huge payments to noble lords. Admittedly, the long wall approach worked better than the room and pillar approach, but the return wasn't all that good to begin with, it would seem like.

Maybe Heading Out can explain a little more about this.

Gail:

It has to do with who gets paid what, at which stage in the process. The numbers here initially are pit costs, and initial sale, but this does not cover the expenses, royalty payments etc that all were added as the coal travelled to the coast/river/canal for shipping. The owner of the land made much more than almost anyone else, and this was in most cases a member of the nobility. The Duke of Bridgewater was one who comes early to mind, and I think was one of the early advocates of the longwall method.

This was a 'property-owning democracy' with very limited voter franchise: owners, employers, legislators etc. Land-owning legislators like 'Lords' mattered a great deal, and could justify themselves within a 'modernizing' rationalist ideology. The system was designed to cheapen labor, but these miners seem to have had 'good' pay rates at 3s 6d per day, on a par with 'trades' such as engineer, carpenter. In the swelling casual labor market, however,

One does not need to be a marxist-inclined historian like Thompson, though, to get the picture.

Edit. According also to Thompson, "Coal was still carried on men's backs up the long ladders from ships' holds."

These would be men in the 'casual labor' sector.

Something to be aware of was that the miners were often paid in tokens, not coin of the realm. These could only be used in the company owned truck shops. The goods bought were often shoddy and might be mixed with fillers, a pack of tea might have tea at each end and sawdust in the middle. Thus the 'money' paid to the miners returned to the mine owners.

NAOM

So you can take more pillars out get to more coal. I once remember this mine that did that and then they had problems. Bad problems. 2007.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crandall_Canyon_Mine

Hi, TF. You must have read my tirade about Crandall Canyon.

A few mines still use the longwall method, but of course we have machines to do it now. A longwall machine looks like a big chainsaw, and really that's what it is. Me, I only used Joy continuous miners in the underground, then "graduated" to a Bucyrus Erie 9R blast hole drill on the surface. Except for the lung damage I have, I don't regret my days in coal. It was good experience.

Nah, I lived it. Could you link me please?

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/6762#comment-684675

Crandall Canyon had, I believe, a strong sandstone bed in the critical heights above the seam that had possibly not broken when the longwall panels were removed on either side. However it gave the critical force necessary to drive the pillars into the floor when it likely failed as the remaining pillars were removed beneath it.

HO

I love these posts you do on the history of energy. We can learn so much from them, and a lot of it is applicable to today.

You should put them together in a book

A copy of Thomas Smith's book "The Miners Guide" can be found on Google Books at:

http://books.google.com/books?id=lnsBAAAAQAAJ&dq=%22miner's%20guide%22&pg=PP5#v=onepage&q&f=false

bob wyman

Говорят вот, что мол всегда нужно иметь свое мнение. Не стесняться его высказывать. Вот прочитал человек данный пост. Поднял уж было руку написать что-нибудь, а писать то и нечего. Прошу прощения за мысли вслух.