Tech Talk: Manually mining coal underground

Posted by Heading Out on May 9, 2010 - 10:35am

Since last I wrote I have travelled to London and then up North into southern Scotland (I write this looking down at the station in Dumfries, having passed the one-time house of Scotland’s Bard). Today I would like to continue writing on some of the historic methods of mining coal, in part, because in certain parts of the world, this is still the way it is done.

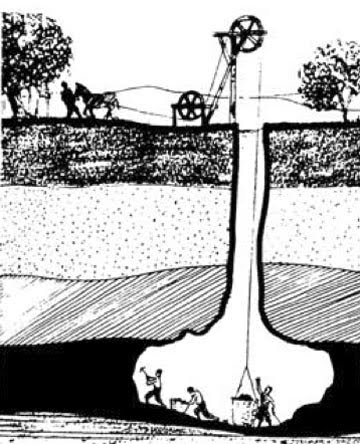

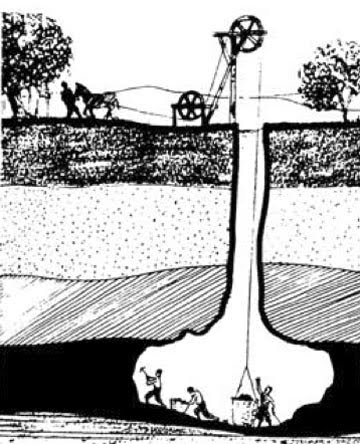

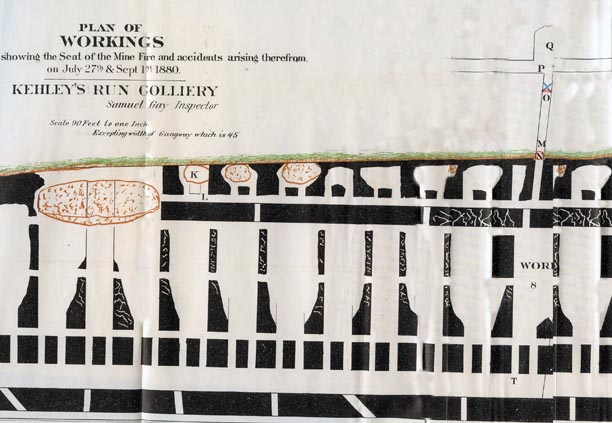

In my last coal tech talk, I talked a little about how mining started where the coal seam came to the surface, or outcropped, and that miners worked their way into the hillside digging the coal out creating both a passage deeper into the seam, and also leaving some pillars, as they widened out the passage way to mine more of the coal. Other times, as the coal became deeper, instead of working from the outcrop, they would sink a small shaft, and mine coal out from around its walls. Because the mines thus had the narrow shaft and then widened in the coal seam they became known as bell pits. They were used in parts of Northumberland as late as World War 1. The miner would break out the coal with a pick, and hand load it into baskets, or corves, that would then, initially be carried up the ladder by children or women. However as the mine got deeper, the ladder haulage would be replaced by a hand-turned winch, or later and for deeper mines, a horse gin or other winching system using an animal.

A two-horse gin is reported to have been able to raise some 2.5 tons of coal an hour.

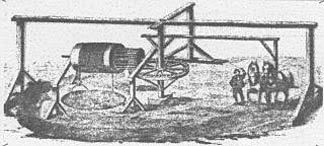

As demand grew, so the underground mining pattern would grow with it. This plan was from the Kehley’s Run Mine in Shenandoah, PA. The plan shows how, from the original drift into the side of the hill, the mine spread out along and behind the outcrop, leaving as small a pillar as possible to hold the roof up.

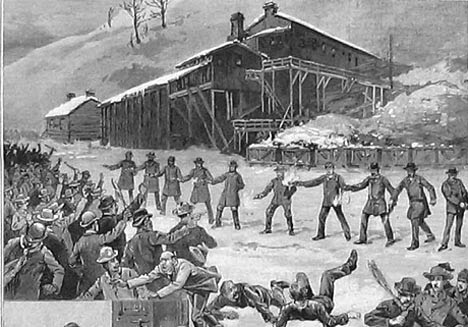

You can see in the illustration how the mine (the current entry is at M, the earlier entry having been closed by the roof collapse shown) mined as much coal as possible to leave the least amount of coal, and that this could cause roof falls. I mentioned one of the fires at the mine, but this mine also raised attention from one of the many riots that erupted between miners, mine owners and their security guards.

Some of these stories have been dramatized in movies such as the “Mollie Maguires”, but it was a grim and vicious set of confrontations based on grim working conditions. In one seven-year period, some 566 miners were killed and 1,665 were injured in Schuylkill County, PA alone.

You might be able to get some sense of the grim conditions from the mine plan. Conditions had been worse in Europe. There are a number of nasty things that can happen in coal mines. As we recently saw and heard, one of them relates to the gas that is given off during mining. Like natural gas from other sources, in ranges from 5 – 15% this methane can be explosive and thus the levels of gas must be kept below this level (hopefully below 1%) if the miner is to be safe.

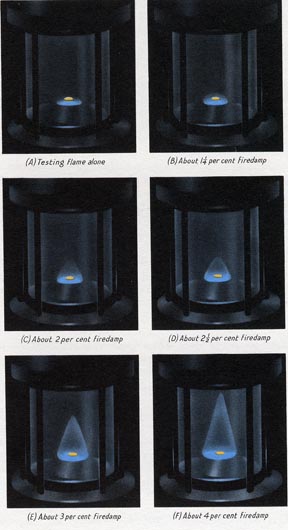

The other gas that had to be watched for was carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide, in contrast with methane (which being lighter than air collects in the roof) is heavier and thus pools on the floor. So that if you were getting down to cut the starting slot in the bottom of the coal seam, you might just drop into a pool. It was called choke damp – though that was also the name given to carbon monoxide, which could also seep out of the coal. All these gases are colorless and odorless so that without some form of detection (the canary for example, or using a candle as a test) they can lurk to catch the unsuspecting. With the invention of the safety lamp (where the heat of the flame is removed by a surrounding mesh of copper wire), it became possible to use the lamp itself as a testing tool. One of my first mining tests was to make sure that I could tell, by the height and shape of the small blue flame of the methane burning over the lowered flame in the lamp, what the gas concentration was. (Each lamp was in a separate hood, and I remember that they had two at the same concentration in the set of around half-a-dozen I had to evaluate).

When the miner saw the flame cone, he would first wave a shirt or towel to stir the methane into the air, hoping that the concentration would fall below 1%, but if the level built up, he might have to leave, or call for more drastic measures to get rid of it. Back in Medieval times there was an individual called The Penitent, who would wrap himself in wet rags and crawl into the mine with a candle on a long stick. Raising the candle to the roof, he would ignite the layers of methane that would gather there, before the rest of the miners came back into the working. Methane, being lighter than air would gather in the roof when the air currents were not strong enough to mix it into the air and remove it.

But, as they mined coal from further away from the shaft, the air would not easily move around the workings, and since the coal would give off other gasses, as well as methane, there needed to be some way of circulating the air. And so the miners began to run sets of tunnels out into the coal that ran parallel to one another, but with cross tunnels (cross-cuts) between them so that they could circulate air around and up to the working area.

For many years, starting in around 1810 the motive power for the air was created by having a fire in the bottom of the shaft, in a special furnace room. Usually these were underground, although there was the occasional one at the surface. Unfortunately, if the fire ignited the surrounding timber that was being used for support, then a major fire could result, killing everyone underground. This was the case with the Avondale mine disaster in 1869, at the time the worst industrial accident in American history; 110 people died.

At first there was only one shaft or tunnel leading in and out of the workings, but a major accident occurred at New Hartley in Northumberland, UK in 1862 where the main beam for the dewatering pump fell into the shaft, blocking it. The 199 men and boys in the mine, virtually the entire working male population of the village, were all killed, It was a result of those deaths that legislation was passed that required that there be two separate ways to get out of a mine. Where the mine is deep underground this means that there are generally two shafts, or more from the workings to the surface. (My Dad was manager at the resurrected mine, and the village school was the first primary school that I went to).

Initially men broke the coal from the solid with picks. To mine more efficiently, they would first swing the pick along the bottom edge of the coal, and cut a slot that would be perhaps a couple of feet deep. Then they would drive the pick into the cracks in the main seam section and break the coal to the edge that they had created. When they worked this efficiently, a man can be very effective in breaking out the coal (about 4 joules/cc specific energy, for those who are interested). The machines mine at around 1,000 joules/cc of coal removed.

As the working face grew away from the shaft, it became too slow to rely on women and children to carry the baskets, on their backs, to the shaft and up out of the mine. ( A woman was reported to be able to carry about 56 lb of coal at a time. So first rails were used to slide the baskets along. Then wheels were added, first to flats, and then to small tubs. At first these were of wood, but then were changed to metal.

Although there are still parts of the world where this type of primitive mining still occurs, and where women and children are used to help get the coal out, in most countries they have been banned from underground work. (This changes was made through the Act of 1842 in the United Kingdom). Taking the coal from the miner or hewer to the shaft was known as putting or hurrying. (I learned it as putting.)

Six year old girl: "I have been down six weeks and make 10 to 14 rakes a day; I carry a full 56 lbs. of coal in a wooden bucket. I work with sister Jesse and mother. It is dark the time we go."

Jane Peacock Watson: "I have wrought in the bowels of the earth 33 years. I have been married 23 years and had nine children, six are alive and three died of typhus a few years since. Have had two dead born. Horse-work ruins the women; it crushes their haunches, bends their ankles and makes them old women at 40."

Maria Gooder: "I hurry for a man with my sister Anne who is going 18. He is good to us. I don't like being in the pit. I am tired and afraid. I go at 4:30 after having porridge for breakfast. I start hurrying at 5. We have dinner at noon. We have dry bread and nothing else. There is water in the pit but we don't sup it."

With time, horses (or pit ponies as they were called) were taken underground and used to haul the tubs. Ponies were used for haulage well into my working career, and leading one was the first underground job that I had, when I worked in the mines before going to college. They served two purposes, being used firstly to haul the coal from the face, but also to haul wood back to the working area, where the miner would cut the wooden props to length and then wedge them against the roof to hold it up while he worked under it.

Because of low cost, the tubs had very crude axles, and so, to go around a turn, one had first to stop the pony, then switch the points on the rail, then start the pony round the turn, then run back to the back end of the tub, and manually twist the tub so that the axles turned to align with the turn. Fail to do any one of those and the tub came off the rails, meaning you had to unload it, put it back on the rails, and then reload it – all the while with the pony standing there enjoying the break.

Because a man with a pick is, though efficient, quite slow, machines were developed where a large number of picks were set into a chain, rather like a large chain saw, and this was used to undercut the coal seam about a hundred years ago. Then holes were drilled into the coal above the slot, filled with a stick of dynamite, and the blast would break the coal into pieces, that the miner could load into tubs. Typically he might load some 20 tubs in a shift, and these were hauled out of the working area by one of the lads, who would then attach those from several of the faces, and pull the resulting train to the shaft using a pony.

He would put his “token” in the tub before he would fill it, and so, when the tub was emptied at the surface, he would be given credit for that coal, providing it did not have much stone in the pile.

It is hard to imagine where we would be without current technology. Your post gives some ideas--regarding practices that were used not long ago, and perhaps even now, in some parts of the world.

The thing that strikes me as I read this is -- We can't go back.

Our current methods use oil, I believe. (Correct me if I am wrong.) If there is a lack of oil availability, we could theoretically adapt to another technology, perhaps using coal only, with sufficient investment and international trade, but this would take time, and may not even be possible, with international debt problems.

Years ago, we could mine coal manually, and carry the coal to the mine mouth by hand. But after years of mechanical mining, most of our underground mines are now so deep that the old methods would not be practical. So that is not really much of a fall back option either.

Heading Out, you give new meaning to getting a pony for your birthday. Thank you for all your great posts.

Couldn't agree more. The easy-to-reach stuff is simply gone.

It would be insane to send men into deep mines without the benefit of complex machinery. Energy extraction, in all of its forms, has tied us to technology and we've overshot the game.

The jig is up. The olden days are no longer an option.

All that said, ditto, thanks Heading Out for an interesting overview of early coal mining.

Not all coal is that deep, some is up pretty high. Huge northern deposits are only hard to reach because they are pretty darned far from the beaten path.

The above 50' seam is in the Beluga Basin of the Cook Inlet region. There is a whole lot of coal up here. Alaska's coal is little bit on the soft and wet side, but is low in sulfur.

Wonder many decades an outcrop like that would have supplied a 17th century population center. Wonder how many days it could run a 21st century power plant.

Indeed. That ought to be in lights up top somewhere.

Gail:

It depends on which country you live in. There are some parts of the world which haven't advanced that much from this, and there are a fair number of seams that are not that thick, but closer to the surface, that are still accessible, but not yet economically minable. (i.e. still a resource not yet a reserve). I'll get around to those in a while.

Our current methods use oil, I believe. (Correct me if I am wrong.)

Most underground mining uses electricity and many open pit coal mines a mixture of electric and diesel.In some cases haul trucks are electric or replaced by conveyor belts.

Why would we even considering going back to using manual labor when human hands and minds can be used to build and maintain wind turbines capable of amplifying human manual labor X1000 fold. Even if a kwh of wind energy costs 25cents, thats the energy generated from 6-8h manual labor.

Good point.

The best selling car in the US costs over $25,000 on average and consumes about 3 times more gas than the best selling car in Europe.

http://www.fordvehicles.com/trucks/f150/pricing/

With $25,000 one can for instance purchase PV modules with a power output of close to 15 kW which can produce 3 kWh on average.

http://www.alibaba.com/trade/search?SearchText=photovoltaic+solar+module...

Of course 20 slaves can also produce 3 kWh on average, but then again they don't just run on sunlight or wind...

There are undoubtedly many options between driving F-150s and running the world's most expensive military or going back to slavery, but they are purposely overlooked by most people roaming around this platform...

Convert coal to diesel or whatever you like and use that to mine more coal using modern methods.

Excellent article. Thank you.

I weary so of the mantra: "We can't go back! We can't go back! We can't go back!"

Of course we can- right down to grunting ape-men shoving pointy sticks at each other.

Ever see that old picture of the horse pulling a car with a guy sitting on the hood?

Like a climber sliding down a sheer slope, clawing at the ground for a hold, it's a matter of how far we slide before we manage to catch ourselves. Normally I try to be hopeful that we only slide back a little, and manage to form a sort of hybrid of the very new with some of the very old. But today I feel a strange sense of disquiet and grimness. I begin to feel like I'd better get out my old flintknapping stuff and start practicing...

Hello Tech,

Just a shout-out from a fellow knapper....

Actually, I think that there's enough steel salvage available that humans will have re-forgotten knapping by the time they need it again!

Errol in Miami

VT,

I believe what Gail was trying to say was that we couldn't go back to this kind of coal extraction in order to keep the electrical grid going (if/when that situation arose) or for any other form of energy harvesting (e.g., heating, CTL, etc). A rough average consumption of a typical US coal plant is about 100 coal cars per day. Multiply that by the 614 coal plants in the US alone;

http://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php?title=Existing_U.S._Coal_Plants

Think we may have been in Dumfries on the same day, HO. I was coming back from Galloway.

Desperate jobs down those damned pits. My dad and most of my uncles spent much of their lives working in the South Wales and Derbyshire pits. I was only ever down one, briefly, myself. Even in the forties and fifties of last century, after all the mechanisation and the safety protocols, and the powerful union making things as good as possible, it was still a hell of a job. I had a mate in Chesterfield, my age, who was buried in a small roof fall his first day down, but got out unhurt. Still not twenty when that happened.

Whether we could go back or not, it would be terrible to try. Hell of a job!

Rhisiart, you are a kindred spirit.

My family comes from several generations of coal miners on Cape Breton Island. You're not kidding when you say "Hell of a job!"

When coal was king and the primary fuel-of-choice for steelworks, locomotion, and ocean travel, all measures were taken to keep the price down which meant dirt poor wages, long hours, six day work weeks, no paid vacation, and few benefits.

Anecdotal story: my great grandfather was killed in the mines in 1940 at the age of 70 by a run away car. He was neither nimble nor fast enough to get out of the way.

There were no miners' pensions in those days (only 70 years - a lifetime - ago) and my grandfather (who fortunately had a World War I verterans pension because he was gassed in the trenches) took his mother under his roof. Otherwise, she would have been left destitute relying on local charity for support.

Life was a day to day fight for survival in coal towns. Everybody was only an accident away from stark penury. Everybody was only a strike away from violence and police raids.

We have no idea how coddled we are right now. We have no idea how recently pensions, insurance, and good wages have become the norm.

If things go belly up and we have to rely on coal again I fully expect to see the re-emergence of those very same miserable conditions - only this time limited to those very few places where mining would still be feasible.

The rest of us may just have to freeze in the dark.

Cheers!

Tom Henderson

This is something I have thought about in terms of family histories. I am blessed to have extensive knowledge of my family roots, and to have been told the stories. My father remembered when his dad got the first car the family ever possessed, and named it Henry in honor of the old horse who got to spend the rest of his days in the pasture. He told me about Fat Grandma and Skinny Grandma (my great grandmothers), how Skinny Grandma had a dirt floor, and Fat Grandma had to go out to a hand pump in the yard for water. Just 75 years ago.

But most Americans have little such family lore. I know a great many people who have no knowledge further back than their own grandparents. And no more than names and places, but not the stories, the personal stuff that makes it come real. It makes it harder to appreciate the good things, when the only comparison to the hard times most folk have is from a book.

"He told me about Fat Grandma and Skinny Grandma (my great grandmothers), how Skinny Grandma had a dirt floor, and Fat Grandma had to go out to a hand pump in the yard for water. Just 75 years ago."

My wife's family had "Little Granny" and "Big Granny" (both of them TINY women). This is what we romanticize, not her grandfather's death in a slate mine after a boiler he tended blew. He'd warned the company for weeks, and after his death, in a time before OSHA or liability laws, the company men came around and said, essentially, "talk about this and you and your family will never work in this county."

Is a return to John Sayles' "Matewan" what's in store?

I just hope we'll re-learn to tell and pass along stories when the distractions (even this forum) become rarities because we work all day and, after our evening meal, sleep when the sky gets dark.

You're correct--it was only 75 years ago.

Go back 5 more, and you'd see my father and his mother, during the worst years of the Depression, picking dandelion greens in what is now a parking lot for a Lowe's in our downtown. I hope that my great-nieces and nephews don't have to return there to gather salad from between the cracks in the decaying asphalt. If so, they'll recall, like a dream, a coddled childhood when every pleasure and diversion was to be had with the wave of a hand or at least a little square of plastic.

Time to re-read "Earth Abides."

All the anectodes reinforce for me how stupid we were to force the labouring class to form unions to get any protection against the owners (and often enough the government police), rather than having governments provide the protections as things should be. Weird thing is, we (three or four generations ago) do that, then today moan about the existence of unions, as if we were all mine owners.

What idiots we all are.

One of my favorite bumper stickers:

"Unions: the people who brought you the weekend"

That is a good one, but these days for many folks the weekend is just the two days they work their third job--still, I bet just about any 19th century coal miner would consider the modern three job grind a pretty soft touch.

Proximity to shallow coal outcrops influenced the location of harsh prison camps in colonial Australia. Conditions in Pt Arthur Tasmania were considered too soft for the worst offenders. Around 1820 some inmates were sent to a hell hole called Sarah Island. At Pt Arthur I believe they mined Triassic coal using skips (carts) on rails. On the shoreline near Sarah Island they mined Pleistocene interglacial coal resembling peat. They had to dig it, load it on to row boats then take it back to the island. No wonder convicts escaping Sarah Island turned to cannibalism.

Let's hope those weren't the 'good old days'.