ExxonMobil’s Acquisition of XTO Energy: The Fallacy of the Manufacturing Model in Shale Plays

Posted by aeberman on February 22, 2010 - 10:26am

Most analysts believe that the ExxonMobil acquisition of XTO Energy (XTO) represents a dramatic shift in strategy by the premier exploration and production (E&P) company, and a validation of shale plays. It is neither. The move represents a considered and deliberate choice that acknowledges diminished opportunities for the oil giant to add and replace reserves. The acquisition acknowledges that natural gas is the only viable short-term solution to North America’s energy needs, and that demand will grow. It implies that ExxonMobil believes that higher natural gas prices will be part of that energy future. It presumes that the company can improve on the flawed manufacturing model that has dominated the way that U.S. shale plays have been pursued.

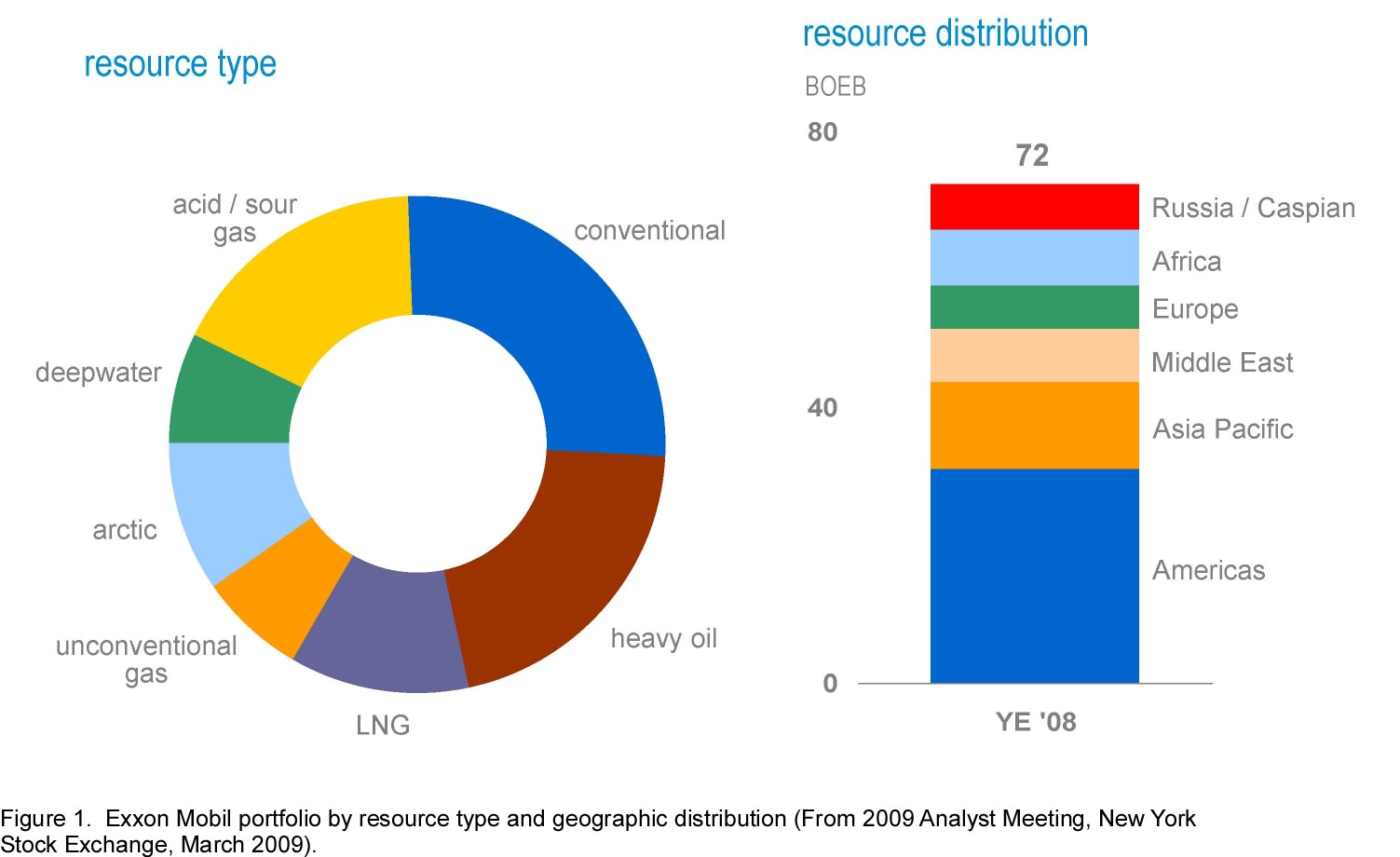

ExxonMobil’s acquisition of XTO only seems dramatic to those who have not paid attention to the company’s strategy and change in project mix over the past decade. Its portfolio consisted of 75% unconventional resources before the XTO acquisition (Figure 1) with a strong emphasis on tight, acid and sour gas, LNG, and heavy oil projects. Tim Cejka, President of ExxonMobil Exploration Company, told The Wall Street Journal last year that his company has been “bullish” on shale plays since 2003 (Wall Street Journal, July 13, 2009). David Rosenthal, ExxonMobil Vice President of Investor Relations recently said, “It’s not a strategic shift” (Houston Chronicle, February 2, 2010).

The Company has pursued tight gas plays in Colorado’s Piceance basin and in Hungary’s Mako Trough for many years. It announced its entry in a shale play in Canada’s Horn River basin in 2009. It leased 20,000 acres in the Marcellus Shale play in 2008, and now has a joint venture with Pennsylvania General Energy that covers 290,000 acres in that play. ExxonMobil also maintains an ongoing commitment to oil sands in Canada.

Reserves

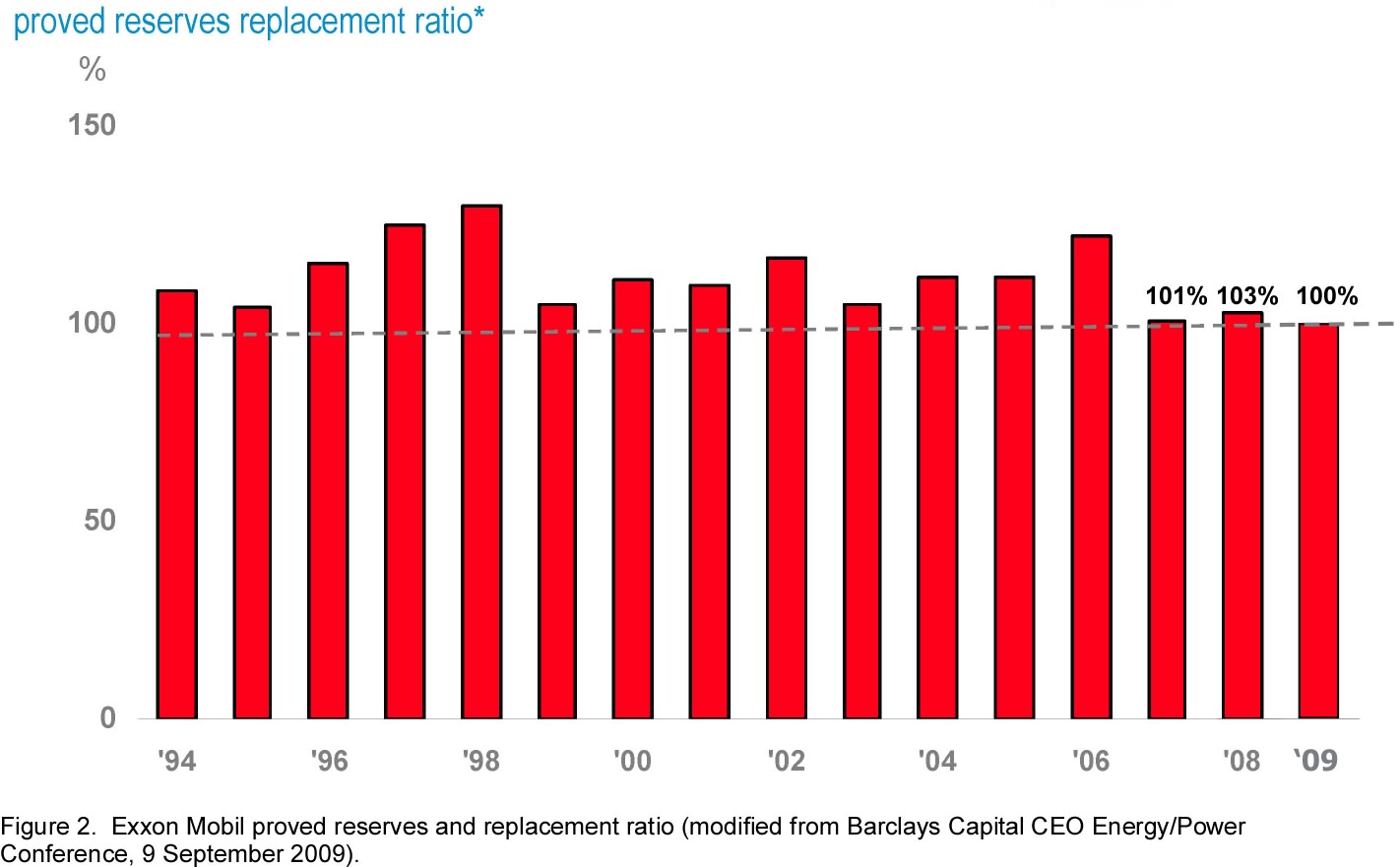

The main driver for the XTO acquisition was reserves, particularly in natural gas. Increasingly, ExxonMobil has had difficulty replacing reserves along with most major oil companies. The worst years ever for reserve replacement were 2007, 2008 and 2009 (Figure 2). While 2008 additions were officially 103% of production, without the contribution of oil sands, which the SEC does not consider reserves, replacement was only 27% (LaVine, 2009). Two-thirds of 2009 reserve replacement came from LNG projects in Australia and Papua New Guinea that were discovered years ago, but completion of processing facilities allowed the additions last year. The truth is that unconventional gas is the only scalable resource that exists for E&P companies that need large annual reserve additions to support their stock price. New SEC definitions allow more latitude in booking reserves especially in the proved undeveloped category for natural gas.

International Risks

Another important motive for the acquisition is the company’s belief that overseas opportunities now carry too much political risk. These projects are too costly and competitive, and the prize no longer justifies the effort. The XTO purchase, therefore, represents another stage in the transformation from an integrated oil company to a capital and service provider. Integrated majors traditionally produced oil and added value by refining it into petroleum and chemical products. In recent years, they have focused increasingly on providing services like building plants and processing LNG for exporting nations, where they add value by providing capital and efficiency. ExxonMobil’s entry into the North American unconventional gas sector moves the focus of the capital and service provider another important step away from the international arena.

Demand Growth and Gas Price

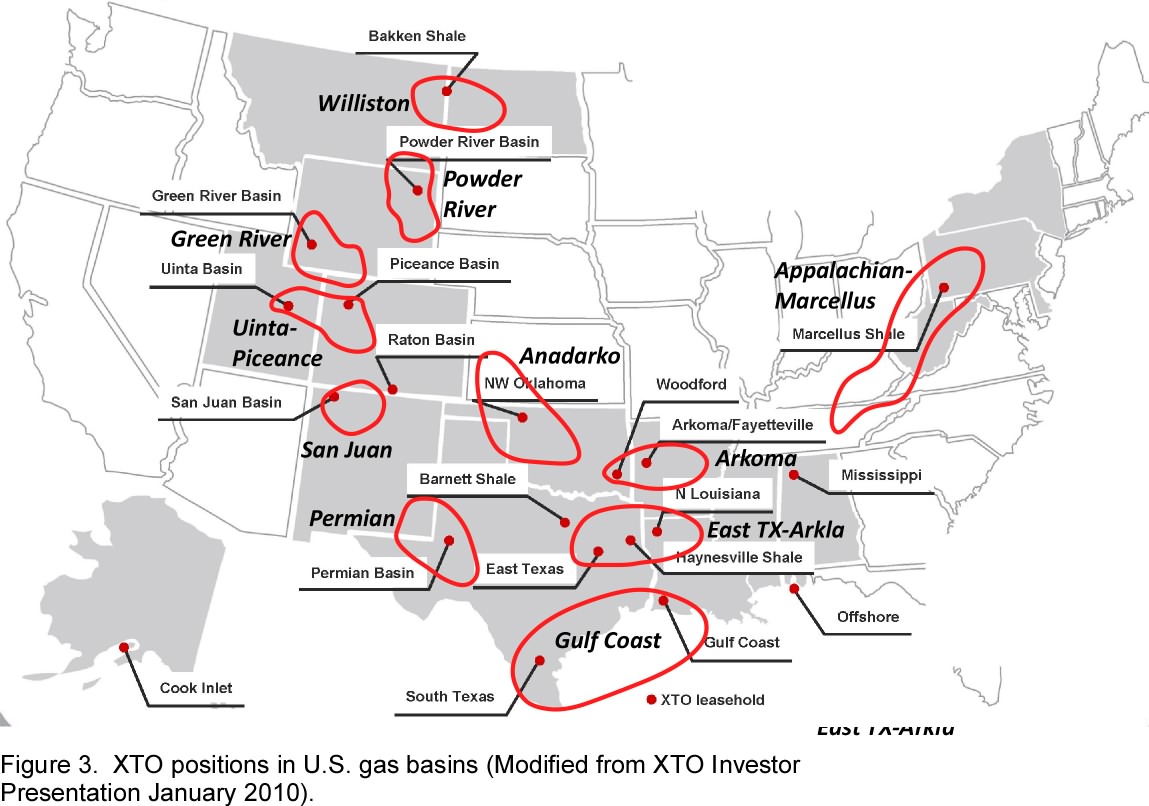

XTO has important acreage in all shale gas plays, but it would be incorrect to overstate its position as a shale gas producer. Eighty-three percent of its production is from tight gas, conventional gas and coal-bed methane reservoirs, with the remaining 17% from shale gas. It has positions in all major natural gas basins in the U.S. (Figure 3). The Powder River, Green River, Uinta-Piceance and San Juan basins contain no current shale plays. The Permian, Anadarko, Arkoma, East TX-Arkla, and Gulf Coast basins contain both shale and conventional plays. Only the Appalachian-Marcellus is exclusively a shale play basin.

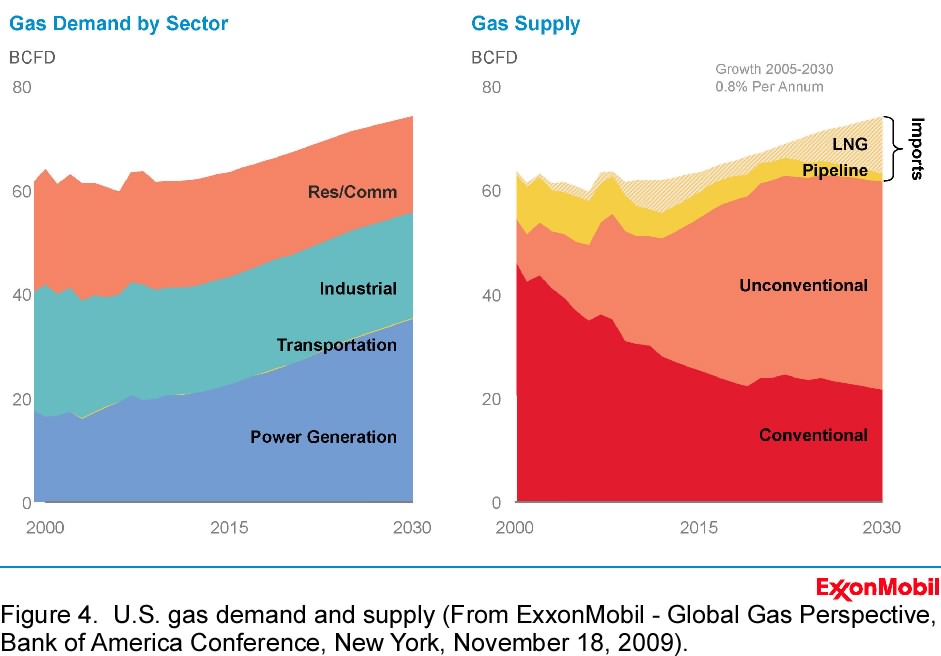

ExxonMobil expects that natural gas demand will increase in the future, and much of the corresponding supply growth will come from unconventional gas (Figure 4). I assume that the company also believes that prices will be higher--perhaps much

higher--in the future. This is because the current marginal cost of gas production is at least $8/Mcf, and prices will eventually rise to meet that cost (Figure 5). If shale gas reserves have been overstated, that unit cost will rise accordingly.

The price of oil, moreover, is likely to increase substantially as oil-exporting countries use more of their subsidized production at home to meet the needs of developing economies and growing populations. While oil and gas prices are not always linked, higher oil costs will drive North America to rely increasingly on indigenous natural gas supplies. This will probably mean higher prices as more costly unconventional resources are tapped to balance this market. Growing emphasis on clean energy sources will further reinforce these supply, demand and cost imperatives. Carbon tax schemes will also push the price higher.

Supply Reality

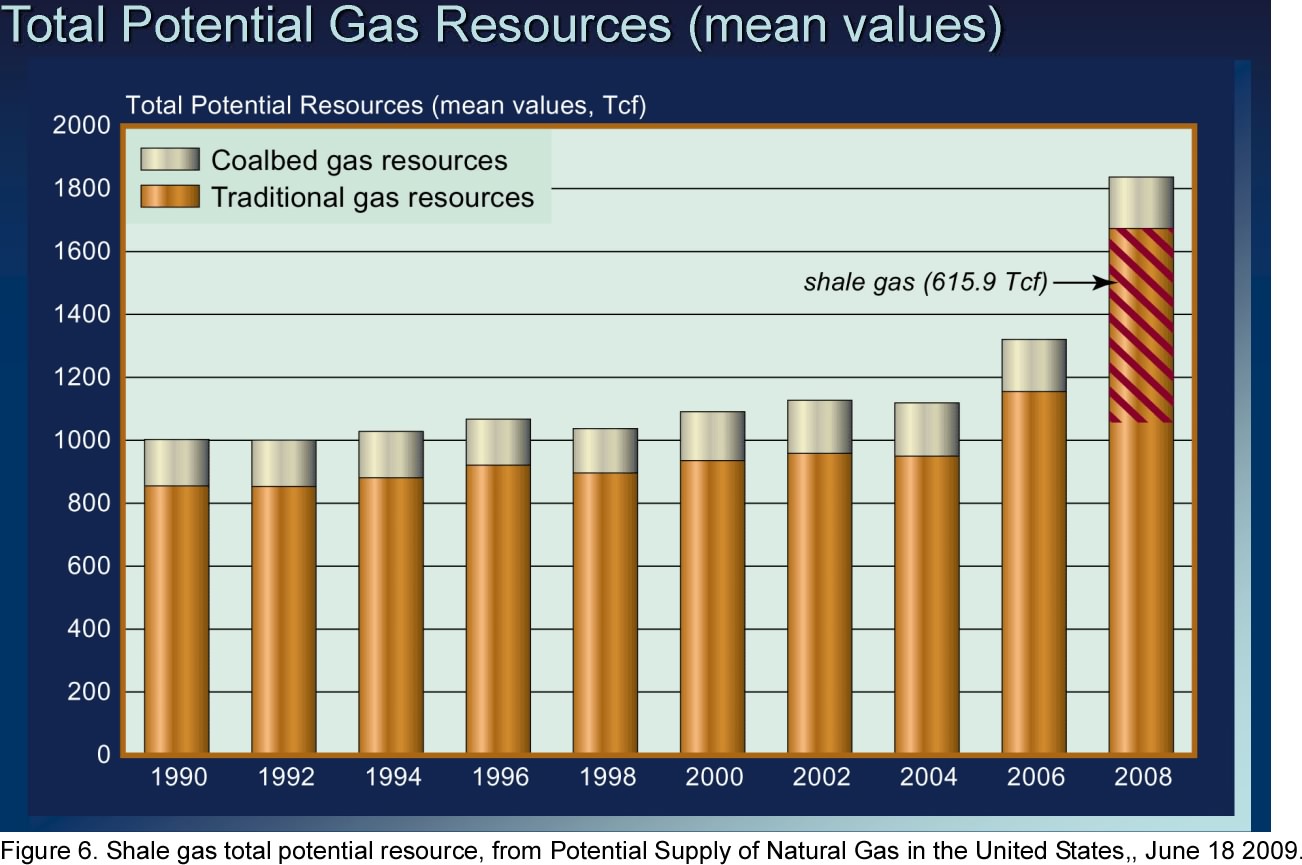

The widespread belief that there is 100 years of natural gas supply in the U.S. because of shale plays is incorrect. Claims that shale gas has resulted in 100 years of supply are based on circular references without underlying documentation, and also do not take high decline rates or anticipated future demand growth into account. The Potential Gas Committee (PGC) estimated 1,836 Tcf of technically recoverable gas resources for the U.S. in its report released in June 2009. Along with proved reserves of 238 Tcf, there are 2,074 Tcf or 85 years of total supply based on current demand of 25 Tcf per year (EIA). The contribution of shale gas is 661 Tcf, or about one-third of the total technically recoverable resource (Figure 6). The PGC estimate of probable resource volume is 441 Tcf, or about 18 years of supply. Shale gas accounts for one-third of that amount, or 147 Tcf, which is about 6 years of supply at current U.S. demand.

Winner’s Curse and a Return to Basics

ExxonMobil’s approach to evaluating and entering unconventional gas plays was antithetic to the manufacturing model. I believe it was comprehensive and systematic, and involved evaluation of major risk elements of the total petroleum system for all North American basins. The Company revealed its North American emphasis in 2007 when Kurt Rudolph, Chief Geoscientist, gave a keynote address at the AAPG Annual Meeting in Long Beach, California.

Rudolph’s talk, “Current Exploration Trends: Prudent Investments or Irrational Exuberance,” described his company’s world view that there were few attractive international opportunities that had not already been captured. State oil companies held all the cards, and were offering concessions that had been recycled over the past 25 years of exploration. Remaining prospects in the international arena were relatively small, because most available blocks were in their second or third phase of appraisal, and fiscal terms were unattractive. Rudolf called this the “winner’s curse,” because if you win a bid round in today’s environment, you lose because the prize doesn’t justify the cost (World Oil, April 2008).

ExxonMobil decided to focus its petroleum-system and basin-analysis evaluation methods and technologies in North American basins where risks and costs were lower, and where financial returns were more immediate. The result was a deliberate and comprehensive assessment and ranking of both conventional and unconventional natural gas opportunities. When XTO approached ExxonMobil about a merger (Form S-4 Exxon Mobil Corp, February 1, 2010), its existing production and exploration positions must been deemed a good fit based on ExxonMobil’s study.

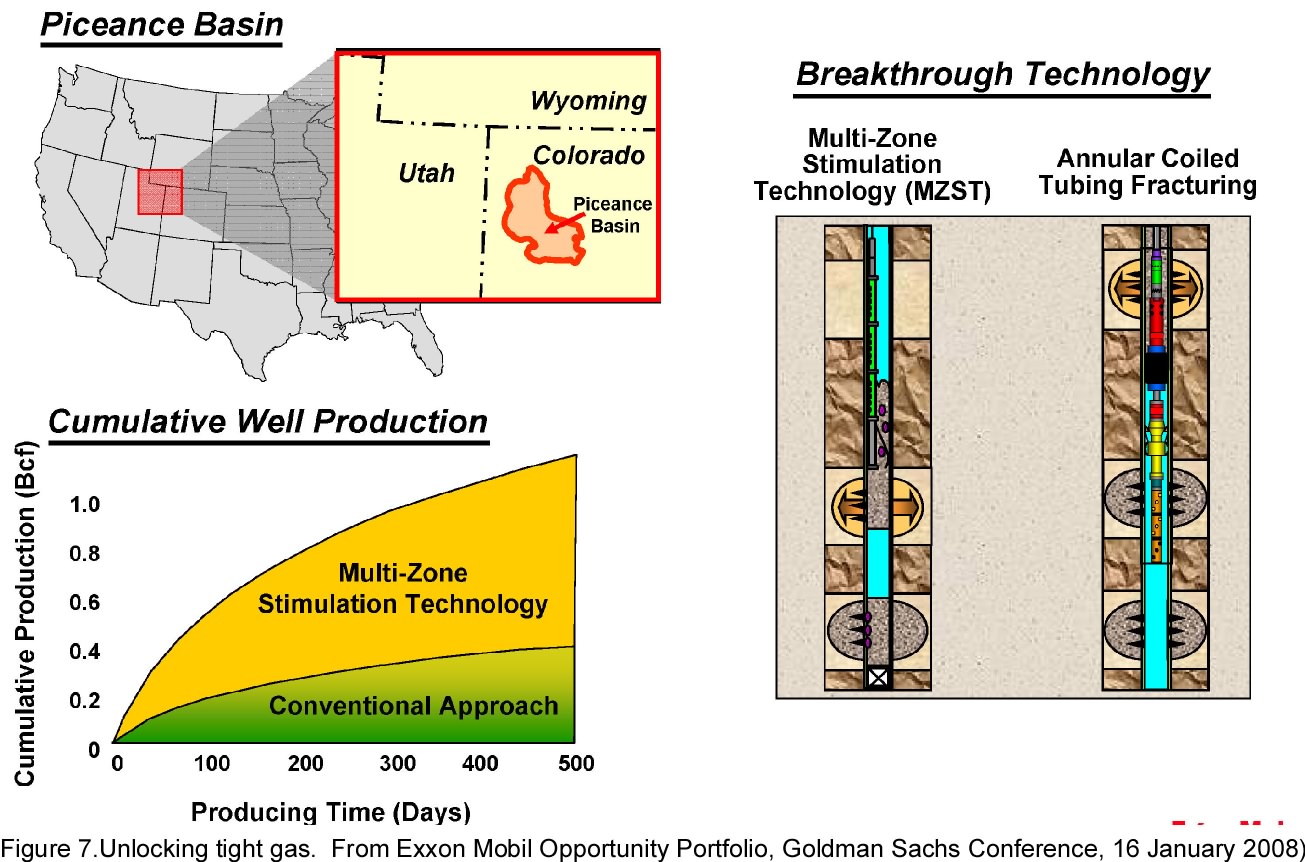

Multi Zone Fracture Stimulation Technology (MZST) and Piceance Basin Tight Gas

ExxonMobil has developed proprietary technologies that allow them to do 50 individual fracture stimulations in a vertical hole on one run called MZST. It has found other technologies to accelerate the drilling and zone perforating processes (Figure 7). The Piceance Basin in northwestern Colorado has been the laboratory for this technology where ExxonMobil has about 3,000 acres in the Piceance Creek-Love Ranch Field area. Gas production in the Piceance Basin is from low permeability Cretaceous sandstone reservoirs. If ExxonMobil can successfully drill and complete vertical shale wells with comparable or better results than with horizontal wells, this would indeed be a breakthrough.

The Fallacy of the Manufacturing Model

Operators represent shale plays as low-to no-risk ventures in which gas is ubiquitous, and success can be achieved and repeated through horizontal drilling and fracture stimulation. They have developed a manufacturing model for these plays in which the fundamental elements of petroleum geology--trap, reservoir, charge and seal--are not critical. This appealing model has not been supported by production results. ExxonMobil probably sees a competitive advantage in taking a different approach than competitors who embrace the manufacturing model.

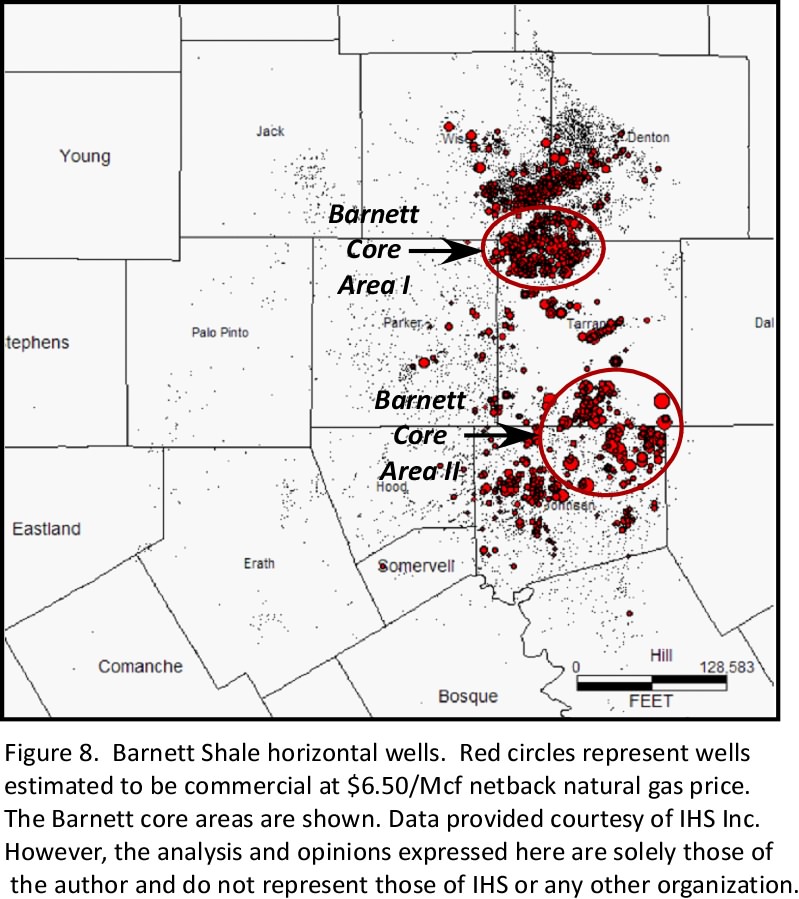

The manufacturing model developed in the Barnett Shale play (Fort Worth basin, Texas), where almost 14,000 wells have been drilled. The greatest number of commercially successful wells are located in two core areas or "sweet spots," and results are not uniform or repeatable even within these core areas (Figure 8). The Barnett Shale play is largely non-commercial because the controls on production are complex and difficult to predict.

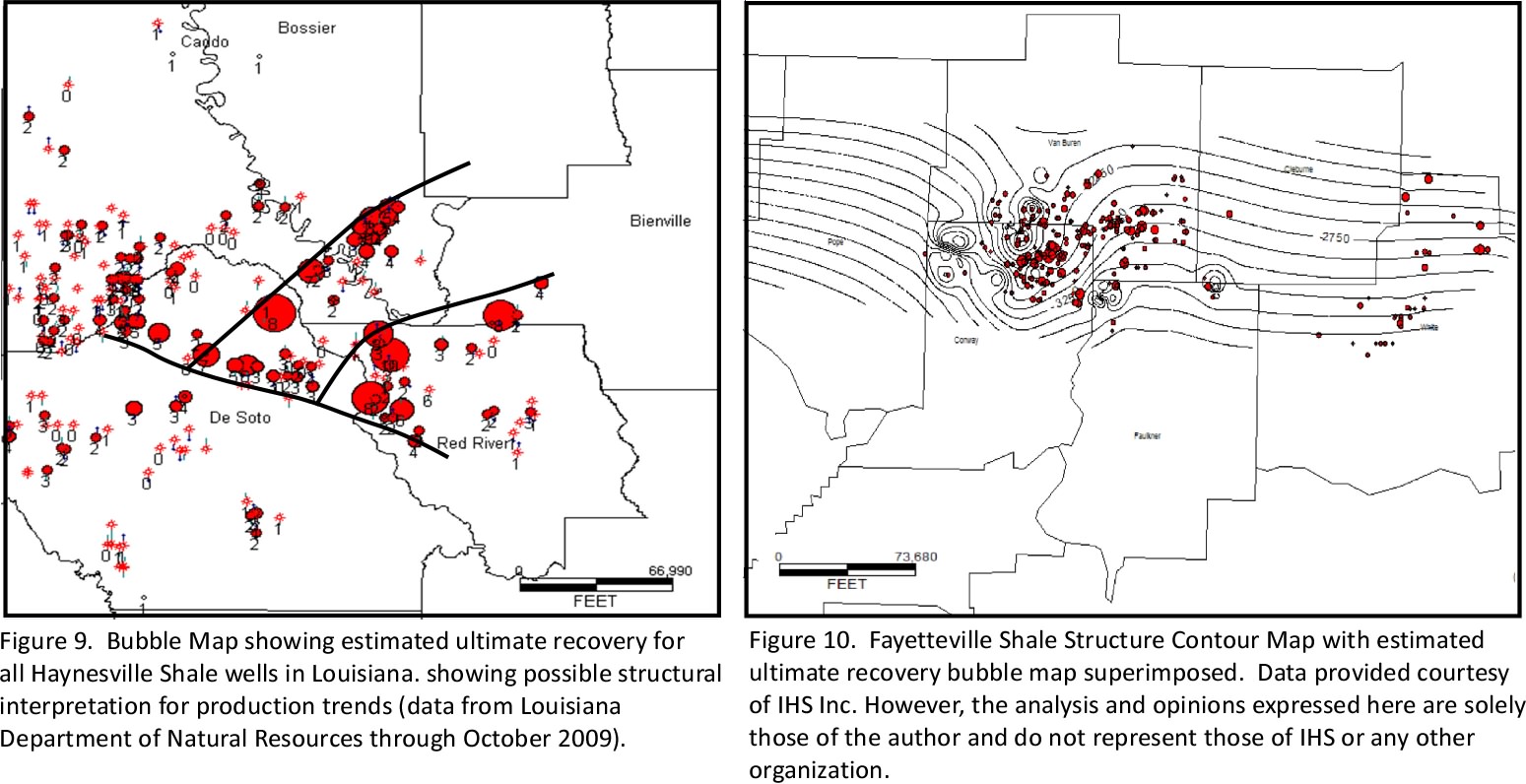

The absence of well-defined structural traps greatly increases risk. Core areas in the Fayetteville and Haynesville shale plays have strong structural control, and have been identified with far fewer wells than in the Barnett play (Figures 9 and 10).

The overriding problem with most U.S. shale plays is the lack of any elements of natural reservoir rock. Shale typically has no effective (connected) porosity, and have permeabilities that are hundreds to thousands of times less than the lowest permeability tight sandstone reservoirs. Unless siltstone or sandstone interbeds are present within the shale that have better matrix porosity and permeability, all reservoir is artificial--it must be created by engineering brute force.

Much progress has been made with completion methods, but unless stimulation produces an extensive, micro-fractured rock face, long-term production at commercial volumes is unlikely. Different fracture methods must be developed to achieve this result with greater certainty.

Conclusions and Implications

The mainstream belief that shale plays have ensured North America an abundant supply of inexpensive natural gas is not supported by facts or results to date. The supply is real but it will come at higher cost and greater risk than is commonly assumed. The arrival of ExxonMobil and other major oil companies on the shale gas scene is positive because they will not follow the manufacturing approach, and will do the necessary science that should make shale plays more commercial. This does not, however, ensure success.

ExxonMobil has come late to the domestic shale party. They may have overvalued XTO's existing wells without fully taking high production decline rates into account. It is also possible that XTO has already drilled the best areas in more mature shale plays, while the potential of newer plays has not yet been established. It is unclear how ExxonMobil’s enormous overhead structure and its associated cost will fit with operating thousands of relatively low-rate gas wells.

ExxonMobil will undoubtedly learn a lot about unconventional plays and operations from XTO staff. It may be difficult, however, to absorb these employees into the company’s culture and structure, and retain them, another indication that ExxonMobil may have paid too much. Despite the new technologies and expertise that they bring, ExxonMobil’s unconventional project in Colorado has not achieved commercial success, and the company has abandoned its Hungary play after drilling a water-producing well (Oil and Gas International, February 19, 2010). Also, environmental opposition to shale drilling and hydraulic fracturing is gaining momentum especially in the Marcellus Shale play, and the entrance of ExxonMobil will provide activist groups with a large and familiar target.

Shale gas plays will, nonetheless, become a permanent and important part of the E&P landscape. ExxonMobil’s acquisition of XTO Energy was based on a deliberate and conscientious evaluation of remaining resource potential in North American basins. Instead of viewing the XTO acquisition as a validation of shale plays, it should be seen as a repudiation of the wasteful manufacturing approach that has characterized these plays thus far.

I believe that ExxonMobil understands the technical risks and uncertainties in these plays, and has made realistic projections of reserves and costs. ExxonMobil’s bet is that efficiency, science and technology will result in commercial success. They bring abundant capital and little debt to plays that have been dominated thus far by highly leveraged companies. Inherent in their assessment is the belief that demand will grow and gas prices will rise eventually to meet the marginal cost of production. It not clear that they fully appreciate the business risks that arise from competitors who will over-produce and keep prices low as long as an undisciplined capital market continues to provide them with money.

References

Berman, A. E., 2008, Winners Curse: The end of exploration for ExxonMobil: World Oil, v. 229, no. 4, p. 23-24.

Clanton, B., Exxon Mobil says it’s not forsaking oil for natural gas: Houston Chronicle, February 2, 2010. http://www.chron.com/disp/story.mpl/business/energy/6846536.html

Form S-4 Exxon Mobil Corp - XOM, February 1, 2010, Registration of securities issued in business combination transactions: http://ccbn.10kwizard.com/xml/download.php?repo=tenk&ipage=6726758&forma....

Gold, R, 2009, Exxon Shale-Gas Find Looks Big: Wall Street Journal (July 13, 2009): http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124716768350519225.html

LeVine, S., 2009, Exxon, the chase for reserves, and the oil sands: Oil and Glory, http://www.oilandglory.com/2009/07/exxon-chase-for-reserves-and-oil-sand...

Oil and Gas International, February 19, 2010, ExxonMobil & MOL quit Falcon JV in Hungary.

POTENTIAL GAS COMMITTEE REPORTS UNPRECEDENTED INCREASE IN MAGNITUDE OF U.S. NATURAL GAS RESOURCE BASE, June 2009: Colorado School of Mines: http://www.mines.edu/Potential-Gas-Committee-reports-unprecedented-incre...

Sanke, P., D.T. Clark and M. Silvio, February 1, 2010, ExxonMobil: The Big Unit’s growth acceleration: Deutsche Bank Global Markets Research Company.

xto is a part of the bakken oil shale play in the williston basin. it remains to be seen if xom will stay in the play. xto got into the play by acquiring properties from heddington and the hunt family. they dont seem to be located in what would pass for "sweet spots" and xto's results are just not that impressive.

furthermore, reserve estimates being cast about by public traded companies are not supported by performance and this seems to apply across the board. performance(to date) supports about half what is claimed by most public traded companies.

eog resources recently made the claim of 850 mbo per well for what they call their "core area". a footnote explains that this figure includes probable and possible "reserves". my own performance based analysis of eog's core area indicates about half that amount.

i dont subscribe to the manufacturing model either, however xom may be smart enough to drill on a more economical spacing than the 80 acre spacing being promoted by nearly all of these shale gas players.

Elwoodelmore,

The Three Forks Bakken play to the east of the traditional Nesson Anticline/Elm Coolee play has good potential, but 850 Mbo/well seems excessive. I have evaluated several wells that have 300-500 Mbo/well potential in that part of the play, but question higher values.

When I first heard about the shale plays and the purported enormous quantities of gas, three questions came to mind. How much is really recoverable? What are the production rates? What are the depletion rates? I assumed the "100 year supply" talk to be unrealistic. Now a fourth question surfaces. Given the less than rosy picture of shale gas, after the depletion and production rates kick in, what's next?

I think the other question, to which we really don't have an answer, is, "How high can rates go, before the result will push the consumer and manufacturers into layoffs and recession?" If the price can't go very high, then it seems like supply will be less than forecasts would predict.

My question about all this UNG ticking time bomb talk is what will happen, and on what time scale; or whether we should care at all. We've been producing from these sources for quite a while now, and catastrophic decline rates don't seem to have made themselves manifest with wells from the early 90s.

How has this played out? EIA used to have a convenient page for production by source but it seems to be gone now. Have we passed 50% for UNG?

KLR,

Unconventional gas, and shale gas in particular, will be a permanent part of the E&P landscape because we have no other options that can meet our energy needs. You are correct in identifying high decline rates as the great liability of shale plays and the need to continually drill wells to maintain production.

There is little doubt about the size of the resource. The question is what will be the cost to provide the product? I suspect that it will much higher than many experts propose, possibly in the long-term range of $10-15/Mcf. This will have a profound impact on the economy that many have not anticipated.

Art

Art, a few comments on this post of yours.

High decline rates are common in shales, and have been for as long as I've been involved with them, which started in the 80's. These characteristic high declines ( excluding the Antrim perhaps ) are also usually accompanied by a hyperbolic decline profile, its final and more stabilized decline rate being as critical for long term viability as its starting point, or the point of transition from initial decline rate to a more flat profile. Using modern shales as an example, the longer term declines for most Barnett wells are pretty reasonable, the most recent information I have on the Haynesville shows that until a consistent behavior in transition from a high, early, near exponential decline to a flatter tail becomes commonly known, the uncertainty around the final EUR ( regardless of economic parameters applied )is pretty extreme.

Having dealt with these declines for a decade or so in industry, I don't consider them a "liability" at all, they simply are the result of fractured dominated self sourced reservoirs prior to transition to more matrix porosity and permeability in combination with some sorbed component.

And in nearly all cases of production in unconventional resources, the instant you stop drilling is the same instant that aggregate production begins to drop, such an event is inherent in the mathematics of aggregation in a naturally declining environment and not a particularly characteristic event for only unconventional or self sourced reservoirs. It should also be noted that these types of resources, upon transition to their extremely flat tails, can easily be producing multiple decades later at a reasonable fraction of their initial stabilized decline rate, and some companies are quite happy to ride these tails for a long, long time. Stable cash flow for minimum operating cost for the mom and pop operations is the bread and butter for some smaller companies in America.

Reservegrowthrulz2,

The problem with the Barnett Shale is that the stabilized decline rate that you mention will probably not become established until most of these wells reach their economic limit of production. The NPV 10 reality is that if wells have not paid out in 5 years or so, they probably never will. The theoretical arguments about hyperbolic decline cannot counter the commercial reality that most wells will never pay out.

Art

Well, that would depend on the economic limit. Certainly, not doing SEC reserves anymore, I don't keep up with operating costs in any particular area, but I also know what happens when wells reach their economic limit....companies find a way to make the economic limit lower.

A representative type curve of Barnett vertical wells drilled prior to 2002 certainly had reached a stabilized decline within about 5 or 6 years, which is reasonable when viewed in the light of other shale gas plays. Certainly I have used stabilized declines as low as 2% during reserve audits without too much trouble in Devonian shale wells, so it is unlikely that a producing well in Texas displaying such behavior wouldn't pass the same test. As to whether or not the turn into stabilized decline takes place before or after an economic limit, well, thats a well by well argument most of the time. Some will, some won't. Certainly the failure rate, failure defined as a well no long producing from any Barnett perforated interval, on all vertical wells drilled prior to 2002 is quite small.

And I am not making an theoretical argument about hyperbolic declines, I have a specific breakdown at the well level for those I evaluated as hyperbolic, and those which I evaluated as exponential.

Reservegrowthrulz2,

We use 1 MMcf/month as an economic limit, and consider that quite generous.

I have little faith in type curves when every well is different but respect those who use them. Vertical wells are not in the debate today since few have been drilled since 2003. There are few horizontal wells that have produced 5-6 years so the stabilized decline rates that you reference are not documented in the critical data set.

Art

1 MMcf/month is not an economic limit, it is a rate limit. As to whether or not it is generous, that would be dependent on the price of natural gas considered. For example, @ $2/mcf you are talking about $2000/month for a gas well, @ $6/mcf its $6000/month for operating costs.

In your analysis are you supposing that the operating costs for a given gas well, undoubtedly without the sort of lift equipment I am familiar with on stripper oil wells, changes by $4G's a month, directly correlated to gas price? Chart integrations, routine welltender visits, consumables within the tank battery, they all increase by 3X in lockstep with gas prices?

If you wish me to reference horizontal well declines, or the time apparent to achieve a stabilized decline, I can do that as well, but not from memory.

As far as type curves, I have read your opinion of them at your website. And while I do subscribe to the "do all the wells" theory the same as you, it is for completely different reasons.

DurangoKid,

Your questions are appropriate. I describe a phenomenon called the drilling treadmill for shale plays. Because of the incredibly high per-well decline rates, operating companies must continue to drill wells to maintain production and support their stock price. This supports the illusion of success but does not address the more important issue of profitability.

There is no doubt that the natural gas resource in the U.S. is vast, but what is the correct price that will support its commercial production? I think that Gail raises the important question about the burden on our economic system if natural gas prices must rise long-term to meet North American energy needs.

Dr. Berman --

Thank you for this informative and very balanced piece on shale plays. I agree with you that producers have been tap dancing around the marginal cost of natural gas from shale, which (I am persuaded) sits somewhere between $7-8/mcf. That cost has little prospect of falling; drilling through solid rock and pumping water (etc.) into the fissures requires great inputs of energy no matter how you approach it. It amounts to, as the industry puts it, 'manufacture' of natural gas, and suggests powerfully that much of the 'easy' gas has been had.

You are betting that XOM will bring more discipline to shale gas exploration, which would fit with its culture and reputation. I have one question regarding this: to what extent do you believe XOM is capitalizing on the shale 'story' and the positive market play that 'adding to reserves' gives a company, as opposed to a hard-headed assessment of how much shale gas they will bring to market?

Again, a great contribution to TOD!

Steve

i think the "manufacture" model refers to repeatability of results, drilling lots and lots of wells, quantity over quality.

i think that is also what the bush administration was trying to promote when they wanted to classify burger flipping as manufacturing.

Elwoodelmore,

There are no manufacturing models that apply to oil and gas exploration and production. I have worked with armies of consulting companies that have tried to make this claim but the truth is that E&P is a non-linear complex process that cannot be evaluated like an assembly line product (I wish it were so!).

The manufacturing model has clearly failed with shale and tight gas sand reservoir production. These are complex reservoirs that require all of the attention to science and detail as conventional plays. The manufacturing model is a ploy to sell the financial market on a product that cannot be commercially viable. Wall Street has, unfortunately, bought the model. Once expectations have been set, it is difficult to re-arrange those expectations.

Art

My interpretation may be too simple, but $8 seems cheap if the gas is used in a CNG powered vehicle, relative to the price of gasoline.

If there was a major push to retrofit its vehicle fleet to CNG it could probably offset the shock of PO by reducing demand in line with the declining supply. More importantly, most of that $8 remains in the US economy. $4 gasoline sees most of the money disappearing into the bank of OPEC.

Of course, $8 gas would put a dent in the rest of the US economy that uses gas - electricity and home heating etc. However, it would be a major push towards conservation in these areas. OVerall, NG could be used as a transition fuel to a low energy future.

In practice, vested interests are and will continue to support the unsustainable, and oil price shocks will send the US economy into further tail spins, and much of the shale gas and coal bed methane and other energy sources will remain cheap and in the ground, under exploited as the US heads for third world status.

Which, from an environmental point of view, is the best possible outcome.

RalphW,

You have a keen view of the reality of oil and gas prices and their effects on the economy.

$8/Mcf may indeed by cheap, although I suspect that the longer-term cost of shale/unconventional gas may be much higher, perhaps in the $10-15/Mcf range. As you suggest, this will have a profound effect on the economy and will push us more toward local sources of resources and will shrink the global perspective.

I agree with you that natural gas is the logical and available transitional fuel between our current oil-based economy and a future based on something else. I see that transition as longer than many experts. The obstacles to funding, environmental and public acceptance of nuclear and coal projects are substantial, and these are on-the-shelf projects that can work today, although we can dispute their economic viability without government subsidies.

Alternative options that are not currently on-the-shelf or are not yet commercially viable must be placed in the appropriate context of having little impact in the 10-25 year time frame. This is a perspective that the public does not grasp and that politicians do not foster, but must be understood. I am totally in favor of these alternatives, but we have to understand that they cannot meet our current needs in a meaningful time frame.

The optimal outcome, therefore, is to apply the best science and technology to unconventional gas resources as a bridge to better alternatives. I am confident that companies like ExxonMobil are better able to do this than the speculative and highly leveraged companies that dominate shale plays today. The overhead structure of big companies like ExxonMobil, however, limits their capacity to deliver commercial results.

We have a problem here.

Art

Alternative options that are not currently on-the-shelf or are not yet commercially viable must be placed in the appropriate context of having little impact in the 10-25 year time frame.

I'm not sure what you're referring to. Wind power is certainly viable, though I agree it can't compete with old, dirty coal, old amortized nuclear or cheap natural gas. It can certainly compete with $8 gas, new coal and new nuclear.

Steve,

I suspect that ExxonMobil is somewhat out of its element in the case of unconventional natural gas plays. They have struggled with the Williams Fork (Mesaverde) play in the Piceance Basin, and have exited the Mako Trough Hungary tight gas play. I think that they are hoping to learn from XTO how to do this correctly, but I am not certain that XTO is an appropriate master since their anticipated reserves in the Barnett and other shale plays are far above reasonable projections based on their wells' performance to date.

The best way to make money in the oil and gas business is to get someone to buy your company and its debt while things are still looking good. That is what XTO has achieved.

ExxonMobil is in a difficult situation. They must add reserves, and have correctly identified unconventional natural gas as the way to do this. Their overhead structure, however, makes the reality of thousands of low-rate gas wells and associated operating costs difficult to say the least.

I have great confidence in ExxonMobil's discipline and efficiency. They are a world-class technical organization with the best staff that I have ever worked with. The challenge here is whether their organization can overcome the inherent lack of reservoir in shale plays to turn a profit that satisfies the needs of a corporate giant like ExxonMobil. I wish them all the best!

Art

Steve -- some operators may have been "tap dancing" verbally but actions always speak louder then words. I was consulting for Devon in Jan 08' when NG prices were in free fall. As prices dropped below $6/mch Devon dropped 14 of the 18 rigs it had drilling in the E Texas SG plays. And paid a $40 million cancellation penalty to do so. Even before prices began to fall the profit margin was getting slim even at the higher prices. Though they were making good wells it was coming at an ever increasing cost as ops went from 2 or 3 frac stages to 12 or more. Multistage fracs improved flow rates but at a significant cost that wasn't obvious as we watched improved performance.

RE: prospect tread mill...I always preferred "cookie cutters" myself. Appeals to my sweet tooth. LOL.

http://www.istockanalyst.com/article/viewiStockNews/articleid/3882933

Chesapeake shifting to oil as gas slumps, crude rises

westexas,

I read CHK's intention to become oilier a few days ago. This is, in effect, an admission that shale gas is not providing what they need for income.

If we examine their oil potential, it comes up very short. The Eagle Ford oil leg has the same catastrophic decline rate as all shale plays. 3,000 bo/month sounds good at first but, when you decline it, it amounts to only about 20,000 bo in the productive life of a well, and a loss of >$1MM/well. If they think that they can do better in the Granite Wash than real oil finders who have been prospecting there since before we were born, good luck.

Art

Since they have "discovered" the Granite Wash, I wonder if Chesapeake might soon be saying that they think that there might be a large oil field on the west flank of the Sabine Uplift, in East Texas.

Much appreciated.

.

Thanks for the terrific post.

Is there a version of Figure 5 that has the companies listed by actual $/mcfe, rather than in alphabetical order?

It would be quite interesting to see who the low-cost and high-cost producers are.

Piccolo,

I would also like to see the Bank of American graph by company! The only way to accomplish that is to wait for the 2009 10-K filings and go through all of the major companies individually. That is a task that I and my associates will undertake in coming months, but it will require some time to produce publicly.

Art

Dunno how gassy COP is, but get a load of this headline: ConocoPhillips Announces 2009 Reserve Replacement Of 141% - WSJ.com

And as per my prediction they are taking a page out of Arthur Anderson's book with some "Creative Accounting":

New SEC regs also allow 3D seismic/oil shale+I forget what else as P1. Hah, let's call it Drilling for Oil on 100 F Street.

KLR,

I attended John Lee's talk on new SEC rules for proved reserves at last month's SPEE meeting in Houston. Companies will take the liberties that they feel are allowed, but Lee's interpretation was that it would be a very cold day that the SEC accepted a seismic argument to extend proved reserves below a known water contact. Here is a link to his presentation: http://www.spee.org/images/PDFs/Houston/Houston_Jan.zip.

Art

Thanks Art. This catches my attention:

What would the process for such a determination be? Here is what the SEC itself says: SEC Final Rule and Interpretation: Modernization of Oil and Gas Reporting: disclosure regulation issues

KLR,

Dr. John Lee's presentation to the Houston SPEE is available online: http://www.spee.org/images/PDFs/Houston/Houston_Jan.zip

He thinks that it will be very difficult to get SEC acceptance for reserves, for example, below a known water level based on a seismic bright spot. At the same time, he does not see that the PUD offset rules have substantially changed and yet we have already seen extremely aggressive booking by the likes of Petrohawk.

AEB

Does shale gas result in the same amount of natural gas liquids as conventional gas? I've checked several sources and cannot find this discussed. My knowledge of shale gas is extremely limited, but it seems possible to me that because shale's permeability is so much less that it may affect the flow of the heavier components.

Propane is an extremely important heating source in some areas, so I hope the answer is that as we get more and more of our gas from shale formations it will not affect the production of propane.

haynesville gas is as dry as a pcf. the barnett has a deeper component which is more like a gas condensate.

elwoodelmore,

The gas and condensate production from the Barnett Shale is related to thermal maturity and depth, I believe. In the Haynesville Shale play, I do not know that these boundaries or limits have yet been established, although they certainly exist.

My understanding is that the Haynesville Shale as a source rock is more of a closed system, and that there are no known associations of oil or gas in shallower producing horizons that can be typed back to Haynesville source rocks. This is part of the argument that supports overpressure--the Haynesville top seal is apparently quite efficient.

The situation in the Barnett is completely different because almost all known oil and gas production from shallower horizons in the Fort Worth basin can be typed to Barnett source rocks.

Art

Engineer Earl,

Your question about natural gas liquids is acute. While some companies claim that their economics are enhanced by NGLs, I have my doubts. The relative permeability to liquids vs. dry gas is a major concern in low-permeability reservoirs. I would personally prefer high relative perm to gas than to the more complicated case of NGLs and condensate regardless of price.

There is also the issue of shrinkage. Basically, NGLs convert to a slightly higher BTU value for the gas that a producer provides, but this also shrinks the gas volume. While I understand the positive arguments about NGLs in shale plays, it seems like a minor issue to me. If you need NGLs to be commercial, I suspect that your play is so marginal to begin with that it may not matter!

Art

Thank you for your article and responses to our comments. Dr. Colin Campbell, when he did his monthly newsletter (this should be a link to his last one) included NGLs in his oil and gas production profile. I've sometimes wondered if this part was more uncertain than the rest since NGLs seem to be more of a secondary product. Yet in some communities they are vital.

Matthew Simmons on the IEA's World Energy Outlook

Was recently looking at some of the work IEA has done on shale gas in their flagship publication World Energy Outlook 2009 and noticed on their website the following comment from Matthew Simmons:

"I recently had the privilege of attending a presentation of the World Energy Outlook and was struck by the quality of its analysis of the supply challenges to simply keep the world's current oil use flat. Adding the equivalent of four new Saudi Arabia's over the next 21 years would be a challenge of epoch importance and adding another two to supply a modest increase in the world's almost unquenchable need for more oil use coming from China, India and Middle East is daunting. This message from the IEA comes from the work done in 2008 to examine the best data available from the largest producing Giant and Super Giant oil fields. The leadership team at the IEA need high praise for taking such a serious and detailed look into field by field data, as well as discussing its implications in the World Energy Outlook" ”

(Matthew Simmons, Chairman Simmons & Company International, 27 November 2009)

Source: http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/leaders.asp

Nicolas,

I have great respect for Matt Simmons, but I have also read the recent optimistic reports on shale gas by his company's research organization, and find a technical shortfall here, as well as a contradiction with many of Matt's positions on shale gas that he has presented recently.

This contradiction needs clarification by Matt before I can comment on his recent plaudits of the IEA who have been consistently wrong in the past.

Art

I can't take anyone seriously who - in the same paragraph - tells us that 14,000 wells have been drilled into a certain area (costing how many billions of dollars?), and then proceeds to tell us it is mostly non-commercial.

Incidentally, just because every single well is not perfectly identical does not mean the "manufacturing model" is a failure. GM and Dell do not produce identical car and computer models, nor are each of their models equally profitable (some models are even unprofitable). In spite of that, for decades they have continued to produce cars and computers, and have found millions of willing buyers.

In the US there were 86,128 exploratory wells drilled in 1984; California's production peaked the next year. Dunno how many of those wells were in CA or what the gas/oil split was; they were 12% of US production then, so maybe 10k+? Or "only" 5k? At any rate drillers like to drill is the take home message.

Are you trying to tell me drillers are drilling just for the recreational value of drilling? Do they like to spend millions of dollars on each well just for the thrill of poking a hole in the ground and watching something come out?

Lol, you're going to have a tough time convincing basically everyone who works at an oil or gas company of the merits of that thesis.

A common characteristic of resource plays is that they have a high success ratio ( defined as the presence of natural gas, not necessarily commercial volumes ) and in such plays the statistical results become critical. Some consider this very characteristic the reason why it becomes "gas mining" as it were ( Southwestern Energys term, not mine ). Economies of scale drive down cost, new technology opens up higher IP's providing a higher IRR, the long lived nature of the reserves tends to mean that under a PV10 measure they are discounted harshly. Once you are 10 years down the road however, everyone is looking around at these low declines covering operating cost and then the usual happens, another industry cycle and presto, instant cash cow.

Considering the number of Barnett shale wells drilled prior to 2000 in a <$3/mmbtu environment, it does seem that industry behavior on what is, or is not, commercial, is open to questioning. Other shale plays developed before the Barnett and the Newark East field, like the Big Sandy Field, the Antrim in Michigan, New Albany, Devonian and Ohio and parts of the Marcellus were certainly drilled in a relatively low cost environment without too much trouble, and it is unlikely that development would have happened if they weren't commercial.

Also, Art's claim that these types of resource plays need structural enhancement is actually more of a sideways economic argument in these unconventional gas shales and certainly is not a geologic requirement. Which means the entire argument circles right back around to what is, or is not, economic activity.

The original work done on these types of unconventional, or continuous, accumulations notes the presence of gas nearly everywhere, and often in places you least expect it, like underneath water in the center of a basin. This isn't necessarily a shale-gas angle of course, but quite a few of the original works on these types of plays was done by Spencer, Mast and Law when they worked at the USGS.

abundance.concept,

Is your objection conceptual because you are unwilling to accept that legitimate companies continue to drill non-commercial wells? How about the real estate debacle where smart companies like Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, AIG, etc. knew what they were doing, and yet managed to not only bankrupt themselves but the entire world?

Our position is not conceptual in the Barnett Shale because we have done the individual well decline-curve analysis, and the economics don't make sense. If you don't like that, please join us because we don't either.

You may not take me seriously, but have you done the work to show that the contrary is true?

Art

How do you know they are non-commercial? If these wells were truly non-commerical, I could see companies drilling a few dozen wells, and maybe even a few hundred wells over a few years, to test this experimental play concept before they finally realized the thing was a bust and gave up. But 14,000 wells over more than 10 years? No.

The real estate debacle lasted about 5-6 years (~2002/03 - 2008) before it all came tumbling down. They've been drilling the Barnett for more than 10 years now. When Chesapeake, Devon, Range Resources, et al go belly-up like Lehman Brothers, I give you permission to tell me, "Told ya so." I'll be waiting.

14,000 non-economic wells. At $2-$5 million a pop. Ya, sure. You might want to consider that it is your decline-curve analysis, and/or your economic assumptions, that don't make sense.

abundance.concept,

I don't want to get into more of a tit-for-tat argument to defend the public position that I have taken on the Barnett Shale play. If you don't believe that I and my engineer collaborator have done the decline-curve analysis and economic evaluation correctly, I can do little to convince you otherwise.

I encourage you to read SPE 119899: Wright, J.D., 2008, Economic evaluation of shale gas reservoirs: Society of Petroleum Engineers Pub. 119899. In his abstract, he states "Three 9-mile areas in the Newark East Field were studied to investigate the economic viability of the Barnett shale gas play...Most of the individual wells are not economic under the assumptions of the study. Of the three areas, only the 75th percentile area was economic when considered as a whole."

For what it is worth, I have struggled to understand how so many companies can drill something that seems non-commercial to me. It really bothers me, and I naturally assumed that I was doing something wrong. I have published and presented this information now for three years, and it has survived the most strenuous of peer reviews--showing the methodology and analysis to engineers, geologists and geophysicists in almost every professional society in the Gulf Coast, most recently to the SPEE in Houston in February. I have presented my findings to an Devon Energy, the leading operator in the Barnett play, and they didn't contest my findings, and admitted that the play was very marginal for them.

The way that I understand it is that most of the wells in the Barnett Shale were drilled when gas prices were above $8/Mcf and rising. At some price from $12-15/Mcf, many of the wells make sense economically. A lot of wells were drilled in marginal areas during the boom years from 2007-early 2009 that never had a chance of being commercial, but wells in the so-called core areas could succeed at gas prices somewhat higher than they are today.

For many of the more experienced operators (and I have talked to them), a few good wells carry the more numerous poor wells and, on balance they don't lose money at current prices with appropriate hedges--without hedges, they lose money.

This and John Wright's evaluation are consistent with our conclusion that 50-75% of the Barnett Shale wells are non-commercial at an average netback gas price of $6.50/Mcf. You can accept or reject this conclusion, but that is what we believe, and that is what the data tells us.

Art

Art -- I'm pretty sure I understand how you're characterizing the wells. But in my world a non-commercial well is one that doesn't net a positive income. It has nothing to do with profitability. All good wells eventually become non-commercial...that's when you plug them. Even profitable is not universally defined. Do you use absolute income or net present value? Some minimum ROR to equal "profitable"? But I think I understand but perhaps others are misreading it.

But I can offer one insight into how many unprofitable wells can be repeated drilled by the same company in a trend. I can't offer a guess as to if the category makes up a small or large percentage of the wells drilled in the Barnett. Many wells (in all trends) are drilled on a promoted basis. Company A spends $X million for overhead, seismic and lease acquisition. They then sell working interest to investors. These can be other companies, funds or individuals. A typical promoted trade: investors pay the promoting company 120% of the $X million they've spent. The investors pay 100% of the cost to drill and complete the well. After the well recovers the upfront costs (120% of $X millions + the completed well cost) the promoting company begins receiving 25% of the future net revenue. In the oil patch this is " a third for a quarter" trade = investors pay 33% of the cost to earn a 25% of the well. Thus a company might drill one unprofitable well after another and generate a nice income for themselves. And keep doing so as new investors come along to fund future drilling. Many of the wells drilled in the Barnett were promoted in this manner but, as I mentioned earlier, I can't quantify the net effect. How successful can a promoter be? In the boom of the late 70's I saw one operator drill 18 expensive exploratory wells in one joint venture program. All 18 wells were dry holes...never generated $1 on cash flow. And the company's senior management retired millionaires. The investors? Lambs to the slaughter.

Then you have to add the public company mentality driven by Wall Street demands for an ever increasing reserve base. This might sound like an extreme example but it is quit plausible: Company A drills 200 Barnett SG wells. Each well generates just $1 more than the total cost to drill, complete and produce that well. In fact, a few might not even recover their costs. And assume the revenue stream pays whatever finance cost might be involved. The company's income goes from $0 to $600,000 per day over that period. And the company now has a gold plated reserve base of over 300 billion cf of NG remaining. And using this cash flow they can continue drilling wells with just a $1 profit margin indefinitely. And why would a company follow this track? Because at the onset their 10 million shares of stock were worthless but now it has a market cap of $400 million. Management can then keep paying themselves their high salaries or call it quits and cash out their stock for tens of millions.

Can this really happen? First- hand experience: in the 90's I drilled 4 horizontal wells into producing reservoirs for a public company. These reservoirs were already producing but very slowly. The new wells increased the overall company rate from 10 million cf of NG per day to 50 million cf. The increase rate did increase the net present value of the reserves. But the 4 wells cost more than that increase. Thus on a NPV basis the effort lost money and no new proven reserves were added to the company's books. Just producing what was already proven but faster. How did Wall Street react? Stock went from $0.35/share to $3.00/share. Nothing illegal. No misrepresented numbers. SEC had no problem. Drilling the four wells decreased the company's profit and resulted in 700% increase in market cap. An interesting side note: this company was acquired via a hostile takeover by a well known and ruthless Wall Street raider. He readily drank the hype and eventually lost his butt. Some justice in all that perhaps.

Bottom line: unless one has a good handle on how wells are funded and who is making money and who is losing, it can be very difficult to characterize a trends "profitability'. Many wells are both profitable and money losers at the same time. Depends on where you sit in the food chain. If your making a lot of money drilling marginal wells you'll keep doing so as long as the sheep...I mean investors keep showing up. It certainly would be interesting to know where some of the folks hyping the Barnett fit into the food chain...wouldn't it.

In aggregate the Barnett has not been economic. If you want some kind of proof other than various studies which have been done, just take a look at the financials of the companies who drill shale wells. Almost none of these firms have created any value through drilling. Some have done a good job here and there by selling acreage, but that's land speculation, not drilling and producing gas. Simply put, they cant generate any free cash flow, and the fact that they are CONSTANTLY raising new debt and equity, while nobody buys back stock or pays a meaningful dividend is the tip off that it's uneconomic.

As for the logic of drilling uneconomic wells, I dont find it nearly as incredible as you seem to. E&P management teams get paid for increasing production and reserves with little long-run attribution to value creation (i.e. the plays being economic). Entire industries destroy value all the time: subprime lending, dot-coms, telecom, CDO's, S&L's in the 1980's, practically the entire mortgage market in the 2000's for christ's sake, autos...the list goes on. Just because a lot of money is being spent doesn't make it economic.

That a large number of non-commercial wells are drilled near peak production is consistent with Ugo Bardi and Alessandro Lavacchi's work fitting peak oil to Lotka-Volterra predator prey models, see http://europe.theoildrum.com/node/5731. Their work suggests that peak production is due to decreased return on capital. Capital peaks after production, so a large number of non-commercial wells are drilled just prior to and at peak production.

Suggest Readers view the following Analysis:

"Natural Gas: Tying Supply, Demand and Politics Together in the U.S. Economy" at the following Weblink:

http://www.naturalgasstocks.com/Karl_Miller/news/1261.asp

I have major issues with the non-commercial shale gas thesis as well. To believe that, one has to presume that Mr. Berman is right while the geologists and CEOs at XTO, Chesapeake, Devon, Plains Petroleum, Talisman Energy, BP, Total, Anadarko, Mitsui, Statoil, ExxonMobil and many others don't have a clue and are pouring more than $100 billion into a non-commercial technology that will lead them all to ruin.

There is another way to look at the very high initial decline rates of shale gas wells. It means you get more of your production (and cash flow) very quickly, rather than stretched out so much in the future. This is an ADVANTAGE from a financial perspective, not a disadvantage. Admittedly, the long-tail of remaining production is still very important to the well's EUR and ultimate economics. I guess we'll just have to wait another 30 years or so for a truly definitive answer about who's right on that one, but I'm betting against Berman on this. Is there some level of shale gas hyping out there? No doubt. But I think it's the conventional rate acceleration drillers and many LNG investments that are going to be in big trouble, not the competent shale gas E&Ps. But that's what makes investing interesting -- everyone gets to have an opinion and place their bets.

Catman,

Look at the balance sheets of the companies involved in shale gas plays. Ask why they are continually seeking new debt and equity from public markets, selling assets, and diluting equity owners with new share offerings. Then look at their debt load. If things are going so well, why can't they find cash flow to pay down debt, but seek further debt to carry on?

These are serious questions. You may doubt our conclusions and positions but they have weathered public presentations to thousands of professionals in the E&P and financial sectors over the past year. Our position has consistently been, "show us the data that proves we are wrong." No company has come forward to take that challenge so far. That does not make us right but it says something about those on the other side.

Just because big, smart companies pursue something like shale gas, does not mean that it makes sense. After all, who imagined that Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, AIG, etc. did not know what they were doing?

Art

I have reviewed the balance sheets of the companies involved in shale gas plays. Most that continue to seek financing are doing so because they are rapidly expanding their land positions in shale plays and have ambitious drilling programs that are greatly expanding their proved and probable reserves. They are not in slow liquidation mode like many of the majors you seem to hold in such high regard. I fully realize big companies can do foolish things. But don't you find it a bit odd that all of the shale gas buyers that you say are being so foolish were likely fully cognizant of your well-publicized research but, from all appearances, are completely unconvinced? And when you say your conclusions have "weathered" so many public presentations, I would observe that anyone can Google your name and readily find a number of competent and technical presentations from credible sources that make the case that your conclusions are hokum and are primarily the result of flawed analysis of an incomplete dataset. One example:

http://info.drillinginfo.com/wireline/2009/09/how-arthur-berman-could-be...

You're obviously entitled to your opinions and to make your case why shale gas is overhyped. But, as I'm sure you can appreciate, you shouldn't expect a free pass on a site that encourages reasoned debate.

this posted at 11:48 est.

Petrohawk Energy Corporation Announces Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2009 Financial Results

http://finance.yahoo.com/news/Petrohawk-Energy-Corporation-prnews-422610...

$37 million net income ? enough to drill 3 or 4 hayneswile wells !

and the rest of the story....

also see:

Haynesville Research Questions Shale Gas Economics

http://seekingalpha.com/article/189836-haynesville-research-questions-sh...

Thanks for that link. Someone commenting had a link to Open Choke:

Ber(man, gstein) and the Haynesville...

i dont disagree with that statement, many of the widely spaced wells are or were economical(excluding land costs) even at $ 3.5/mcf. so what will make the play economical ? drill 1 or 2 wells per section in the sweet spots, imo.

many of the public traded companies are claiming they can drill on 80 ac spacing with the same results over the entire play. forget the 200 tcf potential for this play, forget the 100 yr supply.

a little pixie dust wouldn't hurt either.

Dr Berman

Thanks for your contribution which places a different perspective on reserves

from that of Exxon itself

From Exxon News release of a week ago

Exxon Mobil Corporation Announces 2009 Reserves Replacement

If I may offer myself as a willing target for everyone’s arrow it is MHO that everyone is wrong…and everyone one is right. Something like the story about the blind men feeling an elephant.

High initial decline rate is good/bad: bad because of the obvious; good because you can ready generate a much slower decline rate: just choke the well back to 5% of it’s potential flow rate. Last a lot longer that way. But kills your ROR.

Limited drainage radius: bad -- have to drill lot of wells; good -- no one can drain you from an offset location.

Hyperbolic decline: bad - rapid decrease in flow rate of an individual well; good -- when rate nearly flat lines you have a very stable production base. There are wells in the New Albany SG play in KY that are still producing 40 years after being drilled. Granted they might just be flowing 20 mcf/day (yes...thta's about $100/day net income). Very little NG per well but times thousands of wells it still generates a good base. This may be part of the reason we haven’t seen the cliff of NG some had expected when the bottom fell out of the SG plays: fewer new wells but many, many low decline rate older wells.

Labor intensive after steep decline: bad - not efficient for majors and large independents; good -- very efficient for ma and pa operators. IHMO this is THE reason why the US is the third largest oil producer in the world. Long after Chesapeake, Cabot, etc have disappeared from a SG area those wells will still be producing. But by micro-operators...not the folks that drilled them.

High decline rates/high costs = poor Net Present Value: bad - companies make bad investments; good - companies make bad investments but add to our NG supply. Good for us…bad for them. But that’s Ok because they are evil.

One side point: Not all SG plays were created equal. I consulted for Devon during the height of their E Texas SG play. And they did have a clue, as Catman offers, of the play’s economics. They were so knowledgeable that when NG prices fell below $6/mcf at the end of ‘07 they cut their E Texas rigs from 18 to 4 in just 6 weeks and paid a total of $40 million in contract cancellation penalties for the privilege of not drilling more SG wells. Devon has announced the sale of their huge Deep Water GOM and Brazil oil fields as well as other international properties. All the consultants are gone and they had their third round of employee layoffs. Just a guess but I won’t be surprised if they don't exist in another year. And they did spend billions of $’s on the new technology. And, unfortunately, it has seemed to lead them to ruin. And I meant what I said: they were probably one of the smartest group of individuals I’ve dealt with in my career. Winners and losers in every game…winners and losers. Spending billions of $'s testing a play doesn't mean it's the right bet. OTOH, if you don't swing for the fences you're almost sure to fail. I've seen few companies go under because they drilled dry holes. I've seen many more companies go under because they didn't drill succesful plays. Think about that for a minute.

As noted up the thread, Chesapeake is trying to significantly increase their exposure to oil plays.

IMO, Arthur Berman is to the UNG bubble as Meredith Whitney was to the real estate/financial bubble. Ms. Whitney was one of the first analysts to point out the problems with the real estate/financial model, and she was bitterly criticized by people who had a vested interest in perpetuating the status quo (I think that she actually received death threats).

Saw that WT. Good luck to them. Short of an unconventional oil play it's difficult to imagine that transition developing much of a reserve base very quickly. WT, Rocky and a few others understand that all companies have been wanting to focus on oil ever since I started 34 years ago. NG was always there as second best. But there was a lot more NG potential then oil so that's where the money flowed. I'm not sure how much of Chesapeake's new goal is based upon a fear of imported LNG but that concern was common in many conversations I overheard during my final days at Devon.

Rockman,

I share your high opinion of Devon as a first-class technical organization, and competently managed company. I have done consulting work for them (not on shale but on China), and value that association. It may surprise some of my critics, but Devon invited me to make a technical presentation on my views on Shale plays in April 2009. I spoke to a full auditorium at Devon's Houston office of technical professionals and mid-level managers from many different business units.

They were professional and respectful in their questions, and many approached me after the talk to express their appreciation, and belief that some of the SG plays (Haynesvile, not Barnett) made little sense to them either. Many told me that the Barnett play was marginally commercial at best, and a tough play by any measure. A saving grace for Devon, I learned, is that on most of the original Mitchell acreage, royalties average only 12.5% instead of 25%. That makes a big difference, of course.

I am not so naive as to think that everyone in the audience agreed with my views, and I'm sure that some took strong exception. I bring this up to support your experience that these are first-rate professionals.

At the same time, I share your somewhat bleak view of Devon's future. My colleague RAG did a detailed accounting of Devon's stated costs and revenues since they entered the Barnett play. The gap is currently about $4.5 billion, and will be difficult to close unless gas prices rise to >$10/Mcf immediately. What killed them were their two big acquisitions--Mitchell and Chief, especially Chief.

What this tells us is that they over-valued the wells brought to the table in these purchases. If a well gives up 65% of its EUR in the first year of production, and another 20-25% in the next few years, it is not worth a thing by the closing, and represents an expense and a plugging liability.

The other key realization from RAG's study is the incredible lease operating costs for 1000s of low-rate wells. Devon's stated LOE is $1.88/Mcf. This is because it requires armies of people driving around in the field to maintain an operation of almost 4,000 Barnett Shale wells. It's a real killer.

For some bizarre reason, Devon didn't hedge in 2009 and was only getting something like $3.90/Mcf. That is another real killer. I asked a good friend at Devon why, but he didn't know. The way large companies work, I guess, is that geologists worry about geology, and another department worries about drilling costs, and another yet about P&L (it was certainly that way when i worked at Amoco). So, when competent, loyal employees of shale companies take violent exception to my views on Shale plays, I wonder if they have a very complete picture of the play beyond their responsibility. I'm not criticizing them--it's just the way big companies are. I mean, really, for a company not to hedge is a serious issue when gas prices are low and hedges are available for something higher than netback even if it still means losing money.

Many thanks for your astute comments,

AEB

Art -- So that was you presenting. Consultants weren't invited but I did hear the buzz. I bailed out in July. So true about the compartmentalization. Though I'm a gelologist I worked for the drilling department and had very little contact with the explorationists. Drilling has a very obvious bottom line view of the world: spend $X to drill and put on at Y mcf/d. Didn't know about the lack of hedging but that goes a long way to explaining why they cut back so hard and fast when NG dropped below $6.50. I had also been working Deep Water GOM and Brazil and they had some expensive misses there. Lossing their share of a $200 million dry hole is one thing. Not finding the $5 billion worth of reserves they were anticipating is another matter.

I try to avoid thinking about the fate of so many of those engineers. Over 34 years I've seen many good and talented folks kicked to the sidelines with few options available to them. And I don't think it will get any better soon. Just reviewed a production acquisition deal this morning that made no sense at first look. Selling way below where I've seen deals bought in years past. But with the capex market today there's virtually no way to buy a deal without having most of the funds in hand. And there are few that have the money. This deal may sell for 1/3 of what it would have sold for 2 years ago. And that would have been a reasonable price.

Rockman - you're quite right about compartmentalization in big companies. I've been in weird situations where different departments within the same company wouldn't talk to each other - so as an independent consultant for both departments I had to convey critical information about company strategy from one department to another department. It was pretty strange, but there was a lot of money at stake, and somebody had to do it. In fact upper management sometimes seemed to be hiring consultants just because their employees wouldn't cooperate with each other.

As an extreme case, I recall being at a meeting as a consultant for a software company at the head office of an oil company. We were developing a strategic production management system and we needed head office input. It turned into a bitching session, with the engineers whining about how the current system worked just fine for them. (The real problem was that it didn't work for the field operations people).

Finally, the project manager (also a consultant) turned to the senior company manager and said, "Look, this decision has already been made at a much higher level than yours. There will be no further discussion, and we will get on with trying to implement it."

Although she was a consultant, I'm sure that if she had gone to the VP and said, "Look, this manager is a problem, I need him to be gone", he would have been gone the next day.

Speaking about being kicked to the sidelines - If you want to survive, when a VP says, "Jump!" you only ask "How high?" when you are already in the air. If your survival instincts are really good, you don't have to ask, you have already researched how high you will need to jump.

Dr. Berman--I appreciate the way you dialogue with posters. I understand why Abundance.concept would have difficulty believing that the oil companies would do something which is not clearly in their economic interest. What I appreciate is how you refrain from attacking those who have contrary views, but challenge them to come up with data that supports their views. I also appreciate the way in which you have validated your own data through peer review and presenting data to producers who find no argument against what you believe is happening. In addition to supplying a very interesting post with attention to detail, you express your own puzzlement at the economic behavior of the players, showing that you still have questions as well as answers.

rdberg42,

Thanks for your supportive comments. You are completely correct that much of the company behavior baffles me also, and I appreciate and understand why some people weigh my humble opinion vs the collective positions of many large public companies, and assume that I must be wrong.

I suggest that these people read Barbara Tuchman's book The March of Folly. In this book of popular history, she analyzes 6 or 7 important situations in history where states or institutions consistently followed policies and tactics that were not only contrary to their best interests, but they knew they were doing it!

Examples include how seven Renaissance popes knew they needed to make changes or risk losing northern Europe. The reformation was not just a religious/social watershed, but meant the loss of huge revenues to the Catholic Church.

Another example she documents is how the British lost what became the U.S.A. Almost no one wanted a revolution or to be separate, and the British knew the problem.

A third is how the Japanese decided to attack Pearl Harbor when their prime directive was not to draw the U.S. into the war.

The lesson that I take from all of this is to always separate what makes sense for the organization vs the leaders. In the case of shale plays, the executives of these companies are getting big paychecks, bonuses and stock options. If their companies tank, they are set for life. I am not implying misconduct or deceit, just pointing out that personal motivation is a factor.

All the best,

AEB

Read that ages ago, good book. Tuchman's a two time Pulitzer winner. You also can't go wrong with Galbraith's Short History of Financial Euphoria, which is a short and easy read to boot. My copy was published in conjunction with FedEx so each chapter begins with a glossy blurb, true irony at play.

Its also interesting to me to note that Exxon's 70% owned Imperial Oil investement, is still considering building a $14 billion or so pipeline to the Mackenzie Delta in Canada to access around 6 Tcf of gas there.

If there is so much endless and cheap shale gas in easy to get areas, then why on earth spend $14 billion on a pipeline to get regular gas?

It would make no sense, which is why this whole shale gas play concept is not nearly as good as its hyped to be in my view!

They talked about the pipeline before shale gas, so if shale gas emerges and was so great, why not shelve the whole concept? No one at Exxon is going to throw $14 billion (or their share of that) at a dubious plan. Pigs are flying long before that happens...