Peak Oil: Looking for the Wrong Symptoms?

Posted by Gail the Actuary on February 18, 2010 - 9:56am

If I were to ask 10 random people what they would expect would be a sign of the arrival of “peak oil”, I would expect that all 10 would say “high oil prices”.

Let me tell you what I think the symptoms of the arrival of peak oil are

1. Higher default rates on loans

2. Recession

Furthermore, I expect that as the supply of oil declines over time, these symptoms will get worse and worse—even though people may call the cause of the decline in oil use “Peak Demand” rather than “Peak Supply”.

Let’s think about what happens when oil prices try to increase. From the perspective of a consumer who is already spending pretty much all of his income, it seems to me the result is something like this:

What happens is that many of the consumer’s most necessary purchases tend to be closely tied to the price of oil—things like food and gasoline, and home heating oil. If the price of these necessities goes up, the consumer is likely to cut back on something else. One possibility is to cut back on non-essential purchases—not go out to a restaurant, or not buy a new car or higher priced home. Another possibility, if the consumer is really pressed, is to default on some of the consumer’s promised debt repayments. (The increase in the cost of food and gasoline doesn’t have to be as exaggerated as shown in the diagram for this effect to take place.)

What effect would cutbacks in discretionary spending and loan defaults have? It seems to me that they would look a whole lot like the recession and debt defaults that we have been seeing recently.

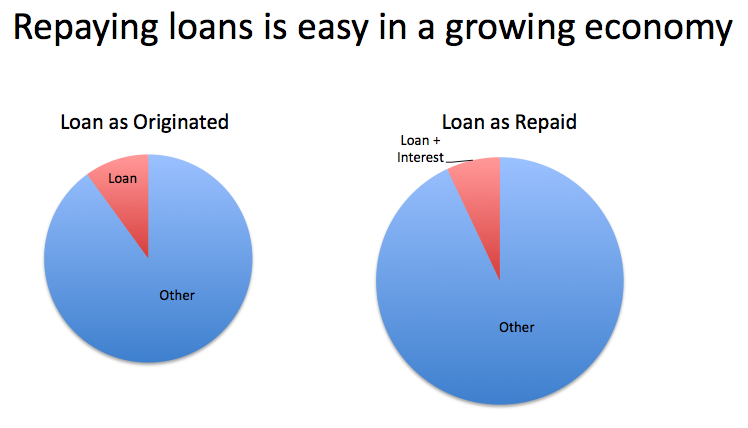

It is possible to look at the debt repayment issue another way as well:

As long as resource extraction is growing rapidly, it is easy for economies to grow, because raw materials needed for growth are present in greater and greater quantities. But when oil—a necessity for nearly all resource extraction and for transportation—is present in lesser and lesser quantities, it is difficult for economies to grow. Without economic growth, it is much more difficult to repay debt with interest, because the interest payment must come from somewhere. Economic growth helps provide the necessary margin for these interest payments.

The period we have recently lived through—from1950 to 2005—was a period of growth in world oil supplies and in the availability of other types of resources using oil for extraction. Economies in general tended to grow, and economists came to believe that economic growth could continue forever.

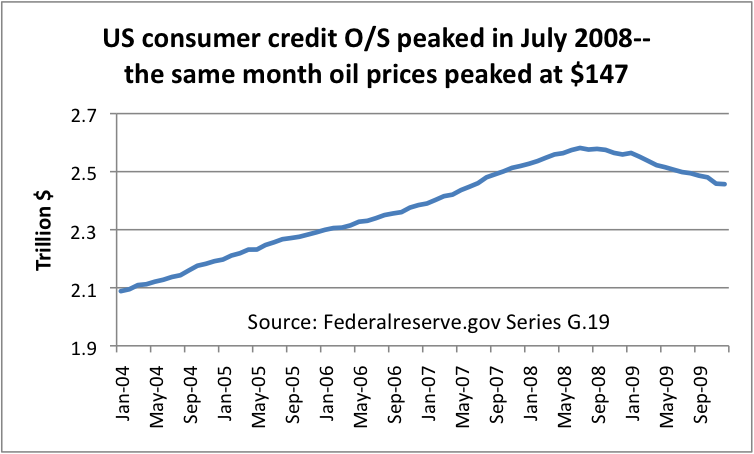

But since 2005, oil production has been flat. In fact, oil production in 2009 was down over the 2005 to 2008 period. This lack of growth in oil supplies led to a run up of oil prices (from $42 in January 2005 to $147 in July 2008, before a drop in prices, and another run up in prices), and has made it more difficult for economies to grow. During the time prices were rising, we have seen increasing disruption of the types expected by higher oil prices—loan defaults and recessionary impacts.

The defaults on loans caused by the higher oil prices have had a feedback impact through the system. When there are loan defaults, banks and other institutions making loans find their balance sheets impaired. This tends to restrict their willingness to make new loans. Without ready access to credit, customers cannot make purchases such as new cars. (Of course, people who have lost their jobs because of recession cannot get credit either.) This lack of access to credit tends to hold down oil prices—through the mechanism we recognize as reduced demand.

One thing that people tend to overlook is the fact that the historic price of oil back when most of our infrastructure was built was quite low--$20 a barrel or less. So even the prices we are seeing now—in the $70 barrel range—are quite high by historical standards. Prices don’t have to be extremely high to have recessionary impacts and to cause debt defaults.

I expect that oil prices in the future will increase (to the extent they do) in a saw tooth fashion, with a rise to a peak, before additional credit restrictions cause a drop in demand, to a new lower level. Meanwhile, our leaders will trot around the world, to Davos and other places, looking vainly for the cause of our current financial problems. If peak oil problems don’t look like they expect, they must not be there!

Here was my early 2007 outlook for the US, in a post-Peak Oil environment, my ELP essay:

http://graphoilogy.blogspot.com/2007/04/elp-plan-economize-localize-prod...

However, something that I was dead wrong about was my earlier assumption that developed countries would outbid developing countries for declining oil supplies. Consumption in most OECD countries is back to, or below, their late Nineties rates, while China for example almost doubled their oil consumption as oil prices rose at about 20%/year from 1998 to 2008, and we see a similar pattern of rising oil consumption in other developing countries in response to rising oil prices.

So, my forecast for the US is that we are going to be forced to make do with a declining share of a falling volume of global net oil exports, and our model--and multiple case histories--suggest that the the global net export decline rate will accelerate with time.

I interpret this as being because the quality of life gained per unit of oil consumed is far higher in the third world than in the US.

There are few (large) countries more profligate in their energy consumption. A middle income American can better cut their oil consumption by 80% more easily than a Malawi farmer can cut his by 20%.

In the early stages of decline we Westerners will feel like we are the losers, because we can afford to lose so much more (and we are already so high in debt).

However, when the fat has been trimmed, it will be the poor the world over who will really suffer. In the US we can trade probably 100M SUVs for electric bikes and only modestly affect our quality of life. If your only transport to get you produce to market is a 125cc moped, the only alternative is to walk.

(I am from the UK - not that different in the grand scheme of things).

Developing countries have the advantage of not being totally invested in a world with $20 - $40 oil. They can develop to the new normal. They also don't have the excessive amounts of personal debt we witness in the developed world. These people don't have to do the psycological work of adjusting to living on less.

There are plenty of (left wing?) organisations who see income much above about $10,000 as addling little in the way of happiness to the recipient. This seems to be the level required to meet our main physical requirements, food and shelter and money to raise children.

Above this level happiness is defined by income relative to your peers. Money as social status only.

There will be a lot of unhappiness as the US goes through collapse. But it will be at the individual level - collapse will hit us one person at a time, as we lose jobs and income relative to our peers.

Only when incomes fall below $10,000 or thereabouts will cause physical suffering. In many parts of the world $10,000 incomes are rarer than millionaires in the US.

Oh and how short our memories are.

Do you remember how big an issue 'third world debt' was to the well being of developing countries, 10 or even 5 years ago?

How do these "third world" countries' debt compare to the US today? Do you think the average guy on the street in a developing country worries about the collective debt his country has accumulated? He doesn't worry about future liabilities such as Social Security or Medicare. He doesn't have to choose between making a mortgage payment or health insurance payment. He likely doesn't rely on a car to get to work. Much of his food is grown locally and he isn't relying on a 401k for his retirement. His energy requirements are a fraction of his counterparts' in the developed world. Is his vulnerability to rising energy costs more than mine? His world is very localized. He doesn't consider 'third world debt".

Don't confuse 'developing' with third world. The latter term is disparaged today, but a billion people are going hungry as we type.

Of course his world is more localised. He doesn't worry about is pension pot - he doesn't have one and doesn't know anyone who has one. He worries about how he will feed himself when he is too old to work. Mortgage? On that shack? Healthcare? There isn't a doctor within 50 miles. He really hopes his wife survives the birth of their fifth child.

Also, the Kleptocrat who took out the loan for his country's development budget ten years ago has long since retired to a nice quiet first world villa.

However, small scale farmers who borrowed a couple of thousand to improve their land with fertilisers and high yield seed stock are now so deep in debt relative to their chances of paying it back they prefer it kill themselves than pass on the debt to their children.

Mass suicides

Ralph, this has been my point all along. Much of the world is already adjusted to "the new normal" because they've been living it. Most folks in the developed world have no realistic idea of how bad things can get and simply won't be able to adjust. Needed/unavoidable changes to how we live (especially in the US) will require people to psycologically adapt to living on much less. I don't think many Americans can get their head around how hard this can be. In their world view, a life without "growth" is unthinkable. AAngel's post on today's drumbeat briefly speaks to this:

I have family memebers who are mental health professionals. They all report that "business is good and getting better".

The catch is the "new normal" is getting worse. As the debt unwind goes on, it is likely to get worse quickly, as international relations (and oil imports) get more and more iffy.

The developing world has also to adjust to an even lower life style because the US and the EU cannot anymore send billions of $ of aid per year (and generous disaster relief). When the economies of the developing countries contact, then those cheap production lines established in developing countries will shut and masses of people will be unemployed there.

I'm not so sure that in the developing world that food is grown locally,

Economic Comparative Advantage Theory applied to many developing areas in the world, saw the destruction of locally grown food, importing corn/maize

from the 1st world, and rice from a myriad of other places by planting commercial crops or focusing on extraction industry. If 1st world farm exports

fail (preciptiously, say in 24 months)

through high energy, fertilizer, water, costs then it will be very difficult to re-establish anything close to self sufficiency in food in these

developing countries in say 3-5 years. You should assume dramatic die off in the these developing countries.

Many 1st world humanitarian projects in developing countries can even make things worse, by INCREASING the dependency on either high energy or high technology solutions (or both), or long logistical chain, non-locally maintainable systems (using Monasanto seeds in Africa is a horrible idea).

In Swaziland where I have the majority of my experience, I continually unwind these 1st world scenarios. There are some serious tensions here though,

I don't know how to bring clean water to some areas without a well pump; however, I would never tie them to the grid because their ability to fund it even 12 months later as questionable (if power can go up 100% from one month to the next, who could budget for that?). In this case I prefer a solar powered system, my personal experience is seeing systems running for 11 years so far.

Why not a hand pump ?

Schoff, are you familiar with gasified pumps? They're very efficient in a crude and maintainable and probably an ideal solution for your project. Let me know if you're not familiar, as I can give you design parameters. They're very simple and ingenious. They'd run of of propane, methane, gasoline, waste digester fuel, compressed air, or what have you. They can run huge capacities and have near no moving parts. Some pipes, and a couple of crappy valves, basically. Proportions must be tinkered with.

basically, you're right; 50+ years of world bank and IMF intervention in governments worldwide have "guided" poorer nations away from self-sufficiency and informal markets and toward exportable cash crops. There are numerous examples, but I did a paper on Brazil once, where farming villages were recruited to stop growing food for themselves, but to grow sisal instead for the export market. Their per capita income went way up, but they had to buy their food at regional markets. Both the sisal market and food prices were beyond their control, so in good years they did ok (albeit with an unhealthy western-style diet), while in bad years they starved and abandoned the land, becoming refugees in the cities.

Among the things they lost was the ability to make sense of anything that happened to them...this being a typical end for those who will give up local self-sufficiency for cash and servitude in the global market.

Here is how it works.

First you get rid of the Colonials.

The Empire had a nasty experience with Colonials going native in North America.

Next you flood the market with cheap gifts. Say tractors. The object is to destroy home grown industries.

Next you start making cheap loans to the Kleptocracy. These will be amortized instantaneously as the money is put into Swiss Bank accounts.But the interest will remain.

Repeat as many times as amuses you. The object is to get the client addicted.

Next offer to assist getting the economy going. Invent a catchy acronym, say ESAP. Doesn't matter what you say it means.

What it really means is "You will work for me for nothing." "Because I have the high moral ground"

If it doesn't work, hey, what have you lost? Some tractors from Bulgaria.

Right Ghung, Besides many of these countries already have a good supply of solar powered vehicles - they are called donkeys.

I would imagine it some sort of creaming curve with most gains near the base with fewer and fewer meaningful gains after a certain per capita consumption

which is a sort of silver lining

Per capita consumption in the OECD can fall quite a bit without a real fall in living standards or more accurately "quality of life"...

don't panic..changing one's gaming console for the latest one every 2 years is not a disaster

I totally agree with this. But I would also say that the "silver lining" is probably shiftable as well, just with more resistance. Where I live, I commute very far to work and everywhere in exchange for VERY low rent. I have cut my non-work commuting to nothing by aligning trips to town with trips to work. I maybe leave the house once a month for nonwork reasons (also, I don't physically go into work very often). This has been easy to do. No pain at all.

Now if I want to cut it further, past that silver lining, there will be economic pain. So I resist it. But if oil was too expensive, or I lost my job, I would assuredly move into the city. It took a lot of pain to reach that breakthrough point, but once past it, my base oil need drops considerably.

This will replay out through the world over and over. Inflation or deflation, doesn't matter, sooner or later something has to give.

There is some base level of energy we need, obviously, and even some base level of liquid fuels. But not anywhere near what we use today.

The question then is how do we best get from here to there?

@RalphW

IMHO, this is simply not true. Think of all the jobs that depend on luxury consumption. The same can be said, when people said that we can cut our excess consumption by say 50% with little to no affect on our livelihood.

Think of all the industries that are built around excess consumption, and the jobs and the tax receipts.

Depends.

Let us take an example - if instead of 4 people driving individual SUVs, if they car pool - only person to get affected is probably the local gas retailer, though quite a bit of gas can be saved.

You are confusing consumption with waste. No one profits from the fuel wasted in an oversize SUV. Maybe GM, MAYBE, but that profit was nothing compared to the waste.

Industries come and go. Think of all the agricultural jobs lost after the green revolution. Think about the shift caused by out sourcing. Think of how computers/the internet and disintermediation killed the middle man. People adjusted. Things went on.

Your right there is a problem with allocation of wealth in a energy shrunk economy because how do you employ all these service industry folk facilitating consumer consumption?

and that is a real problem granted... as a politician would say.. "a host of challenges"

but the bottom line is there is enough energy "left in the tank" to reduce per capita consumption substantially and build a sustainable future with a sane understanding of population limits.

"...trade probably 100M SUVs for electric bikes..."

Good grief, it's February and people still can't remember the existence of winter, when the roads are icy and even four-wheeled vehicles slide off into the ditch...

Paul, you just gotta have the right tires.

Yah, but why do pix like that always show wide-open spaces where there's nothing else to be hit by, instead of the crowded places where most people really drive - and slide around? No tire can protect you from that.

Jail time might encourage drivers to keep their vehicles under control.

Hit 34 degrees F today - saw several bicycles out and about. I might do some errands tomorrow by bike. The problem with cycling in the northern states in the winter is just one thing - motor vehicles. If we used our FF to plow the roads and horse whipped any motorist that struck a cyclist, cycling in the winter would be a great way to get some exercise and save burning FF.

Not that I expect any rational approach to personal transportation any time soon - hmm.. probably never.

LOL.

An appealing and amusing thought.

But no, they are armed.

Hi Arthur,

A few years ago, in Milwaukee, a guy was cycling on a city street when car full of younger folks pulled up next to the guy and started harassing him - throwing junk, squirting soda, calling him names. After a bit of that fun they pulled away but had to stop at a traffic light. The cyclist caught up with them and starting firing a pistol into the car, killing one of passengers. The cyclist departed down a side street and was never identified or apprehended.

Although one could take some morbid satisfaction for revenge of the underdog, it is really a sad commentary on city life. I suppose the kids in the car could have started shooting back and perhaps killed the cyclist and perhaps some bystanders (which is pretty common with these rage type shootings).

Anyway, it was beautiful here today - 34 degrees, bright sun, low wind - got in a very nice bike ride running an errand into town.

I commute to work by bicycle year round. The biggest challenge in my experience is wind; the cold, dense, winter wind is noticeably harder to pedal through and uncomfortably cold too. Snow isn't so bad because, even this winter, there's snow on the roads only intermittently. While it's falling the snow is better than rain, it's only a problem when it collects on the streets. I find I can ride on either fresh snow or packed snow. Snow that has been packed by car traffic into ruts in some-places but remains loose in others is impassible. Transiting from from loose snow to packed snow, at low angle of approach, is like riding over a curb, it steers the wheel right out from under me. I find it's easier to push the bike and ride home in the afternoon after the streets have been plowed and salted.

Another year-round bicycle commuter here. I don't enjoy the rain so much, but riding in the snow is one of the better things in life, and we do get a few good snowstorms a year. On bad mornings I drive my daughters to school in the car, then park it and ride 6 miles to work. The most dangerous thing about driving in the snow is all the other guys driving in the snow; on the bike, however, I'm on the bike trail mostly and perfectly safe.

Hi emcourtney & daxr,

My single bike is a 2-wheeler and I know exactly what you mean. My wife and I ride a tandem trike. The trike will handle all kinds of ice, snow, ruts (up to 4 to 6 inches) with non of the problems I have on my regular bike.

I wish wind was my biggest problem in the winter. I'm with daxr, the danger from cars triples in the winter. And, the best bike in the winter is a trike - but, visibility becomes even more of a problem. Overall, my winter cycling is limited to days with good visibility and relatively clear roads - just because of cars.

Good grief Paul, how many thousands of years did people survive without SUV's or any sort of powered vehicle at all. Heck I walked 10 miles to school in the snow every day growing up. Well OK it was only 1 mile. But even the advent of domestic animals to ride and haul stuff is quite recent. The crash will come sometime, and whether or not we think we can survive without powered vehicles we (or our children, but certainly our grandchildren) will have to. This is not at all question of what we want, how we want the world to be, what we think we can deal with. This is a question of what we have to deal with when the wells run dry. Those who get in shape now by walking or biking and dealing with some hardship will likely be better prepared for the end of the age of oil.

That's the operative word - they survived and nothing more. IOW except for royalty they lived as mere beasts. So what?

True enough in the abstract, walk through any Walmart to see the need. And yet, in the sense I think you mean here, it's still mainly a game for strapping young folks, especially men, plus a smattering of genetically lucky older folks, just as it has always been down the millennia. But about the other half or three-fourths of the population ... ?

An assumption. They may have been happy and fulfilled just surviving. There is evidence that they lived full, rich lives:

(You probably recognize where the images come from --your own bucket :-)

The one on the left seems pretty good to me. On the right, yeah, somebody always seems to get the s#!t end of the stick :-(

I think the diminished oil demand in developed countries is due to two factors:

1. The developed countries have exported most of their (basic energy intensive) industry to developing countries due to production cost benefits.

2. Developed countries' consumption of oil is done by the end consumer more so than in developing countries, and with less money to spend on "everything else", even when the economy picks up, it takes longer for the cash to reach the pockets of the end consumer (ie. "job recovery"). Thus less oil is spent as a component of "everything else", as the category includes everything from discretionary car trips to "stuff" bought at the local mall (which gets there by diesel-powered truck).

We'll be in trouble when the good times have rolled for a couple of years, as China oil demand continues to rise, developed countries' consumers get in their old habits, and net depletion of oil fields is too big to hide with reserves/temp production increases. Actually, any of the above three is enough to make this a problem, together they are a catastrophe.

CN, I have to agree.

Increasing oil consumption with declining production: a disaster. Say decline is 2%/y and demand increase is 2%/y. Since consumption cannot be bigger than production the difference is allready 4% then.

Demand destruction in the US has been primarily in sectors other than gasoline:

Other oils, i.e. industrial applications, residual fuel oil, i.e. bunker fuel for ocean transport, distillates, i.e. diesel to ship goods around, etc. I assume the experience in other OECD member nations has been similar. Jet fuel has decreased sharply as well, much more than gasoline, which is exhibiting strong signs of inflexibility in its demand.

People in the developed world consume more oil per capita obviously but how much of that is domestically sourced - i.e., American made plastics - I'm not sure about.

Good numbers KLR.

Clearly people are still driving around as much as ever. I am surprised by the size of the drop off in diesel and "other oils", which I presume includes oil used as plastic feedstocks.

Railroad traffic has been down, and they have taken this chance to scrap their oldest, least efficient locomotives. Some city bus fleets are now on cng, though this would be a minor change. Many industrial/stationary engines are now NG rather than diesel, so this may be part of it.

Ultimately, there is still LOTS of potential for reducing gasoline usage - we have barely scratched the surface...

In regard to oil prices, the 2009 annual spot crude price of $62 was higher than all annual prices prior to 2006, and more than four times the $14 annual price that we saw in 1998. While these are nominal prices, it's interesting to compare oil prices to a basket of auto, housing and finance stocks.

In regard to monthly prices, the January, 2010 spot price of $78 is almost twice the January, 2009 price of $42, and the January, 2010 price is higher than all prior January prices, except for January, 2008 ($93).

Furthermore, in the Thirties monthly oil prices hit bottom in the the summer of 1931, and then increased at about 11% per year from the summer of 1931 to the summer of 1937. It appears that global oil consumption only declined one year, in 1930, rising thereafter throughout the Thirties.

IMO, from 2010 forward we are looking at annual increase in oil prices, unless and until the global demand for net oil exports once again falls below the long term declining global supply of net oil exports.

Westexas,

I'm sure you are aware that the plunge in oil prices during the 1930's had a lot do do with the discovery of the East Texas oil field in 1930, the largest oil field ever discovered in the Lower 48.

A lot of the deflation of the era was due to the adoption of agricultural machinery, trucks, diesel locomotives and other labor saving equipment fueled by the cheap oil.

ELM 2.0

(Edited to correct some numbers)

Once again, I'm looking at some numbers that scare the crap out of me. Let's see what you guys think

Let's follow the progression from conventional wisdom regarding oil supplies to what I shall call ELM 2.0.

Yergin and Lynch assert that the worst case is a production plateau many decades from now, either in the 21st Century or in the 22nd Century.

The Peak Oilers say no, we have either peaked or we will shortly peak, and we are looking at a low single digit annual decline rate in global oil production.

The Peak Exporters say no, we are looking at long term accelerating rate of decline in global net oil exports.

But I never really ran the numbers regarding increasing demand in oil importing non-OECD countries. Brace yourselves. ELM 2.0 follows.

First, Sam's best case is that the 2005-2015 annual (2005) top five net exporters net export decline rate will be about 2.8%/year (from about 24 mbpd in 2005 to about 18 mbpd in 2015). Since net export declines tend to show an accelerating rate of decline, his 2005-2025 best case is that (2005) top five net export decline rate will be about 5.5%/year (from about 24 mbpd in 2005 to about 8 mbpd in 2025), which would be a net export decline rate of 8.1%/year from 2015 to 2025.

The observed (2005) top five net export decline rate from 2005 to 2008 was about 2.2%/year (EIA), which is in excess of what Sam's best case shows.

The problem for the US and other OECD countries is that we are being squeezed between an accelerating rate of decline in global net oil exports and rising non-OECD consumption. From 2005 to 2008, China and India's combined net oil imports rose from 4.6 mbpd to 6.0 mbpd, an annual rate of increase of about 9%/year. Note that China's domestic production is showing signs of a peak.

So, for the sake of argument, let's extrapolate this 9%/year rate of increase in net oil imports, and let's assume that they obtain all of their oil from the (2005) top five net exporters.

In 2015, Chindia would be net importing 11.3 mbpd, versus projected net exports from the (2005) top five of 18 mbpd, leaving 6.7 mbpd for other importers. So, the non-Chindia net exports from the top five would fall from 19.4 mbpd in 2005 to 6.7 mbpd in 2015, a decline rate of 10.6%/year.

In 2025, Chindia would be net importing 27.7 mbpd, versus projected net exports from the (2005) top five of 8 mbpd.

Incidentally, another metric is Chindia's net imports as a percentage of (2005) top five net oil exports; Chindia went from 19% of 2005 net exports to 27% of 2008 net exports (from the top five)--a 12%/year rate of increase. Based on Sam's best case projection for the (2005) top five and based on the 2005-2008 rate of increase in net oil imports into Chindia, it appears that Chindia would be consuming 100% of net oil exports from Saudi Arabia, Russia, Norway, Iran and the UAE some time around 2018, eight years from now.

"The problem for the US and other OECD countries is that we are being squeezed between an accelerating rate of decline in global net oil exports and rising non-OECD consumption."

That's the whole thing in a nutshell. Will "we" (OECD) accommodate "them" (non-OECD).

I would put it the other way around. I think that military efforts to try to force oil to our shores will be counterproductive.

I don't think there is a military way to force China to use less oil ...

I agree evnow. But I wonder if we could us military force to make us use less oil? Now there's a conservation approach I haven't heard of yet. The politicians are to afraid to raise motor fuel taxes but perhaps a few strategicly placed claymores down at the Shell station might do the trick. Hmmm....yeah....that's the ticket.

Rockman, I agree, the military could force us to use less oil. The standard way to do that is for us to be at war. Then rationing can be done to save the fuel for military operations. To work we would really have to be at war (not that we aren't now but to date there has been no call for rationing to support Iraq and Afganistan). However, to actually be in a wider war would use more fuel, so the question would be could we enforce enough rationing at home to actually end up saving fuel. And of course we would need a casus belli but that could be created easily enough.

On the other hand the military could just take over the country and close gas stations and seize cars. But then they would have to constantly put down insurrections which would use extra fuel.

On the other hand the government could admit that oil is running out and call on Americans to conserve. No scratch that. Not possible.....

Sad but true oxi

The first thing that comes to mind is how much capital we borrow overseas every single day, to keep our little governmental boat afloat here...

The second thing that comes to mind is how much accumulated debt we have...

of course everyone knows we're like the crackhead-on-the-corner nation when it comes to how much of a hole we've dug with the rest of the world, peak oil just being probably the final straw. Financially, its still amazing to me that anything keeps working.

Westexes, I really do hope you publish soon.

Anyway, it seems this is one of those "yeast in a petri dish" moments when calculations show that you havn't got eons of growth but just a few moments left.

Of course Chindia won't be importing everything because feedback loops will start to kick in. In nature these are things like famine reducing populations. In our case it will be recessions, depressions, sky high prices...

Do you think the Chinese have doen their sums? Didn't you give them a presentation to chew on at one point?? Maybe this is why they are agressively expanding 'renewables' but I can't see any evidence of wanting to put the brakes on their nascent car culture -quite the opposite in fact.

Nick.

I think that our long planned update to the top five paper is getting better with time (I'm finishing up a major oil project, hopefully we will have something out shortly). A chart showing the increase in Chindia's net oil imports as a percentage of (2005) top five net oil exports is going to be stunning--from 19% to 27% in just three years, from 2005 to 2008. Or, alternatively, the non-Chindia share of top five net oil exports fell from 81% in 2005 to 73% in 2008. One can see where the trend is headed.

Westtexas,

I truly think your promised papers will be good reading. But I also wonder whether you have factored in to your projections the certainty that higher oil prices will act as an even stronger disincentive for less-wealthy countries to increase their oil usage than it will for the wealthier economies.

That's what I used to think too, but what the recent data show is a consistent pattern of non-OECD countries increasing their consumption as oil prices rose at 20% per year from 1998 to 2008, while OECD consumption in 2008 was back to, or below, late Nineties levels.

Here are some examples that I used in our ASPO presentation. Approximate increase in oil consumption, from 1998 to 2008:

China: +93%

India: +62%

Kenya: +48%

Morocco: +30%

Also given the fact that some many developed countries like the US are functionally bankrupt--because of vast unfunded government obligations--I'm not sure that "wealthier" is accurate now.

-I think the reason is that we are not talking about countries but groups of individuals and there is a small but ever growing % of Chinese and Indians that match or superceed Western individuals in their capacity to out-spend 'us';

"16% of 3 Billion = 96% of 500Million"

-in addition this "wealthy 16%" are possibly commiting a much greater fraction of their wealth to Energy/Oil and 'maximising its return' rather than simply burning it to go down the Mall. The first computer is used for spreadsheets, word processing, education and productivity; the 2nd is a PS3...

Regards, Nick.

"Most recent"? JODI can fill in the blanks for the latest year. BP Data on annual consumption goes back to 1965. KSA consumption YOY increase over this span of time averages 3.88%, China 7.74%. There isn't much in the way of illumination here - consumption of oil increases linearly in developing nations just as inexorably as population.

Exactly. For example Chindia's purchase power will also have its limits, as these economies cannot grow forever - be it due to the limited resources or due to the limits of their foreign trade balance.

And as soon as the non-OPEC imports hit their economical limits and start to decline OPEC will have less money available for domestic consumption. This will limit the export-land-skewness. But unfortunately this limit will take effect much too late to prevent major economic damage to the importing nations.

I would make that "rising high-value non-OECD consumption." China and India can put an incremental barrel of oil to better use than the US, on average. For example, in India an extra barrel of oil is more likely to be turned into kilowatt-hours to power a PC for another chip designer (lots of private firms there with their own generators because they don't trust the reliability of the grid). An extra barrel in the US is likely to go into something of less value. As net exports decline and prices increase, oil will tend to flow from low-value activities to higher-value ones. Absent supply limits, the OECD countries have been able to afford low-value uses for oil; developing countries, not so much. So US consumption drops as poor people take a few minutes to plan their shopping trip to use less gas, and India's consumption increases as they do more circuit design.

There's probably a Ph.D. dissertation somewhere in trying to do a systems dynamics analysis of how things might play out. Simple economics is not the only factor. If the OECD countries were to stop outsourcing chip design to India, it gets harder for India to put that incremental barrel of oil to a high-value use, and slows the growth in their demand. Anyone want to bet that if unemployment for chip designers in the US is high enough long enough, Congress won't take some action?

The incremental Oil consumption is likely to be for a person who goes from riding a scooter to a car. Or a person who goes from riding a bicycle to a scooter.

Considering how important running a PC is - a generator in a designer facility will always outbid an individual driver.

But. I'd probably argue that even in the above cases India is putting the oil to better use (increasing the standard of living of the driver) than what we will probably do here.

Exports from Iran? Which exports? According to the late Dr. Bakhtiari - rest his soul in peace - 2015 to 2018 could well be the period in which Iran's net oil exports go towards zero. See slides #25 to #27 in my slide show I did in the Treasury Theatre in Melbourne last August http://tinyurl.com/kwku23

Emergency Planning after peak oil 2005-2008 3rd and final oil crisis:

http://www.crudeoilpeak.com/pdfs/1

So, my forecast for the US is that we are FUBAR!

Fubar?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FUBAR

Without a doubt FMagyar

Well, the rich will outbid the poor, but that may not be measurable by which countries buy the most oil. For instance if China uses it's oil to produce stuff that is sold in the US, then the oil really went to the US, with some value add done in China. Who does the consumption ultimately is more important than who buys the oil in determining who is outbidding who.

Ilargi, over at Automatic Earth had a post yesterday called Did peak oil cause the present financial crisis?

The reasoning in his post is that if one can find other reasons for the financial collapse, that proves that peak oil was not part of the problem. With peak oil, we would expect to get to the current situation, with without derivatives and all other things that contributed to the problem.

Furthermore, there is another connection. When we could no longer get growth from oil, we turned more and more to debt based products and financial instruments, so this, in itself, contributed to the collapse. But peak oil, and its limitations on growth, was really what was behind the shift to more and more unsustainable debt. As Gregor said, when oil become more expensive, the developing world shifted to coal, while the developed world "replaced their lost demand, lost credit, and the loss of cheap energy the best they knew how: with paper".

They're in denial, Gail. I don't go along with all of the stages of grief junk, since it is poor science. There is no doubt, though, that denial is a step, and anger is another. Tea Party is part of the anger.

Meanwhile, the signs continue. 10-yr Treasuries are a 'mid-term' look at the bond market. Today they are at 3.727%. On the 8th, they were at 3.59%. And they trend upwards. Of course, the place to look for sudden death is the short term, as compared to the long term US debt instruments. If you see very short term (now at 0.83%) rise above long term (currently about 4.7%), you can look for real problems in a hurry.

For those who are interested, here's a nice discussion from CNN Money:

http://money.cnn.com/popups/2005/news/yield_curve/frameset.exclude.html

Craig

that makes so much sense to me...

is it surprising that money fleeing the financial sectors headed towards commodities or that the peak price of a barrel was on at the same time as the collapse of Lehmann's

what follows is the the debt unwind... huge volumes of this money just disappeared into the ether

what is the price of oil now relative to the total volume of money compared to July 2008?

would I be surprised if it was higher than it was?

does that question have any meaning anymore (if ever)?

I'm deeply disappointed in Ilargi. I think he's losing it. Stoneleigh, at least, has some interesting things to say, but she tends to sound like a broken record after a few readings.

TOD is increasingly becoming one of the few places to find pertinent articles and insightful commentary.

Ilargi is fine. His take on derivatives is correct. I personally think he discounts the oil issue too much, but he's not losing it by any means.

As for Stoneleigh... come on, being consistent is not broken record syndrome.

Entropy is an interesting perspective.

I think it would be a good thing if they published here once a week, like they used to do, remember the Canadian roundup? Those posts were well ahead of their time, really prescient. We were yapping about $140 oil back then... they were explaining CDS defaults and deleveraging.

It's clear Ilargi has some sort of grudge against TOD and will believe ANYTHING to completely dismiss the possibility that peak oil might have a hand in the current crisis. He will even believe conspiracy theories (that "elites" purposely crashed the economy to time it with peak oil) rather than accept a peak oil explanation.

As for Stoneleigh--she has gone completely off the rails. She mis-applies fractal geometrics to the blatant pseudo-science of "technical analysis" of stock market charts.

She is no better than a reader of entrails.

So the basic moral of the story is: The majority of humanity is continuing to live beyond its means for the nth generation, except there is little "credit" left in the world.

Looks like the ol' Cree-indian prophecy was spot on:

I keep hearing Money makes the world go round....

Nobody ever tells me Energy makes the world go round, except on the OIL DRUM.

Time is needed to develop new technologies, nuclear or other. Where can we acquire that time? Will the newly found natural gas replace oil in the intermediate future and buy us a few decades to get our house in order? I am a big fan of advanced generation nuclear power, especially LFTR and IFRs. My hope is that they may provide safe, clean electricity at a price lower than dirty coal so that we can get the climate change monkey off from our backs. Of course even if we were to find cheap, clean electricity we still have the need for liquid fuel. Could efficient high temp thermochemical hydrogen separation form water be an affordable substitue synfuel when used to chemically reduce carbon dioxide to hydrocarbon?

I would love there to be a tech solution as I'm a techy but look at Westexes timeframe above... We have not many decades but mere years before 'the pickly hits the fan'... The net decline rates are going to be played out as higher prices/volatility/recessions and depression.

How will we transition to an 'electric culture' in these timeframes and with the inevitable reduced access to credit? Will it be left to Governments to further burden themselves upto the eyeballs with subidies for would-be Prius owners? :o)

Oil a $ under $80 as I type.

Nick.

I think it all depends on how fast the oil decline is. If we can cut huge amounts of consumption NOW, we can save our asses for a few years, decades. If its business as usual, we better hope the oil rigs can keep up. The people i hang around with, talk to have no mental capacity to realize that gas stations at some point will go empty.

Hi John,

From my POV, if we have a stable electrical supply, I can manage most other problems. No electricity is a real problem for any hope of surviving (we are really old folks).

BUT, I just don't understand how nuclear or any other technology can prevent a very painful future. IMO, federal government mandated extreme conservation (one child family), and efficiency (100 mpg personal vehicle) is the only way we will have enough energy generation capability to keep the electrical infrastructure going.

And, I see no way that measures like this will be implemented in an appropriate time frame.

For the sake of our grandchildren we need to make an effort to ease the painful future. It is doubtful that the pain can be prevented. In addition to world overpopulation we have the prospect of a planet with a lower carrying capacity due climate change. Stewart Brand in his book, Whole Earth Discipline, suggests that with the urbanization move, women are choosing to have smaller families. He predicts that the growth of the human population will turn negative before reaching nine billion. That may be too optimistic of an outlook. Recycling, substituting additional energy for extraction of minerals from lower grade ores will be necessary. Societies will need to restructure in order to be less dependent on inefficient private vehicles. In India new high-rise buildings house the workplace, shopping mall, recreation, and living space. There is no need for private transportation and the carbon footprint is modest yet about 300 million Indians enjoy a standard of living the is similar to that of middle class Americans.

The life expectancy in this world for people who without benefit of electricity is terribly short. We really need to attend to the infrastructure of our electric grid and develop safe clean and cheap generating capacity. I was thirteen when the REA reached our farm. That was the one of the biggest steps forward in technology of my life. This computer and the communication revolution is also awesome. It is this information age that gives me some hope that the window to the developing world has been opened and if we can give them safe Liquid Fluoride Thorium Reactor (LFTR) technology they will have electricity to operate their factories so that all the world will be better off.

Nobel Laureates, Eugene Wigner and Edward Teller as well as Alvin Wienberg, the patent holder of our current light water reactor, all endorse the LFTR as the best reactor technology for domestic power. Since during the cold war the LFTR could not produce plutonium for bombs, the funding for research reactors of this type was cut off and Alvin Wienberg was fired from his position as Director of Oak Ridge National laboratory. He was fired because of his strong support for LFTR type technology and his instance upon reactor safety.

Now is the time for the federal government to reinvest in the research and in the training of future scientists to carry on clean safe energy development projects. We can do no less for our grandchildren.

"...federal government mandated extreme conservation (one child family)...I see no way..."

Correct. Fuhgeddaboudit. Out in the real world even the merest mention of population gets drowned in rivers of invective against "depopulators" and "eugenicists".

I think "local" is the only practical way to talk about it. That is, focusing on solutions to your own country's problem is the right way, while trying to solve another country's problem is bad; focusing on your own state's problem is the right way, while harping on someone else's state's problem is bad; looking at solutions to your own county's problems is good, while meddling in your neighboring county is probably bad...and so forth.

The last century of trying to address population issues would have gone much better if people minded their own business before minding the businesses of others. For much of the century, the US was the leading cash sponsor of "population control" efforts all over the globe, while politely declining to even have a domestic policy on population. I believe the last time there was an official discussion here was under Nixon, who ended it - saying that people here should be left to decide for themselves how big they wanted their families to be. The hypocrisy was much more obvious to other countries involved than it was to anyone here.

Concerned northener: Thanks for your quote. I have another one:

Indian Chief ‘Two Eagles’ was asked by a white U.S. government official,

‘You have observed the white man for 90 years.

You’ve seen his wars and his technological advances.

You’ve seen his progress, and the damage he’s done.’

The Chief nodded in agreement.

The official continued, ‘Considering all these events, in your opinion, where did the white man go wrong?’

The Chief stared at the government official for over a minute and then calmly replied, ‘When white man find land, Indians running it, no taxes, no debt, plenty buffalo, plenty beaver, clean water. Women did all the work, Medicine man free. Indian man spend all day hunting and fishing; all night having sex.’

Then the chief leaned back and smiled,

‘Only white man dumb enough to think he could improve system like that.’

We've had financial downturns in the past, yet it was cheap energy/resources that provided the cushion that allowed us to bounce back. Now we find that our reliance on oil is a liability rather than our salvation. Oil and finances are now so joined at the hip that we find ourselves facing the perfect financial storm. Oil will not be the stimulus to grow our way out of our current credit/currency delima. In past posts I've been hammered for saying "this time is different". This time it is. The oil bank isn't lending anymore.

Ghung, you have that right. In fact I would say that the longer we look to oil for salvation the more it moves from being a liability to being our downfall.

This time is different. Not only will oil fail us, it will fail the world because thanks to globalization the whole world has become interconnected.

IMO, Peak Oil/Peak Exports was both a trigger and an accelerant--like a hiker dropping a lit match in a dry forest, filled with dead underbrush, just as the wind is picking up, and then air tankers drop napalm, instead of fire retardant. The firestorm was inevitable, it's just a question of what would start it, and how bad it would be.

Yes, that's it. Ilargi didn't disagree with the idea that high oil prices were the trigger, he disagreed with the idea that "peak oil is the driving force in our present financial collapse". "Driving force" and "trigger" are two different things. The forest fire analogy is pretty good, though I don't know about the napalm bit!

But the other question is what role did low oil prices play in the run-up to the credit problems? As in, low oil prices during the 80s and 90s contributed to people's expectations that they could buy more and live farther away than they did before. It also no doubt had effects on economic growth during that period. Again, I wouldn't argue that energy prices were the "driving force" - that probably comes down to demographics and generational cycles - but it contributed, maybe strongly, in the background. Would exurbs have ever existed in a world of $2.50+ gas prices?

I think this way about the fall of Rome. They had a constant inflation problem, and no one has really figured out why. The Romans never really understood it either. But they were constantly drawing down the supply of one of their biggest energy sources, wood, making it more expensive each generation to get their biggest energy source and primary building material. Their manufacturing base followed their wood supply until they ran out of defensible territory for high-quality wood supplies. Then they were in the box we may be headed toward - no ability to bring on new supplies to counter depletion in existing supplies. But they had a renewable resource to work with, so they went through centuries of growth and decline cycles.

That's my understanding of the situation. Based on the historical experience of the last four decades, one might reasonably have expected high oil prices to bring about an "ordinary" recession, but not a near-total melt-down. Based on what we now know about the financial hanky-panky that was going on, one might reasonably have expected that some triggering mechanism, not necessarily high oil prices, would eventually have brought about the kind of collapse that we have actually witnessed.

I do, however, have a couple of questions that I haven't resolved in my own mind. First, the historical experience of the last four decades to which I alluded encompassed a period when it was still possible to increase global oil production. Assuming that we are past, at, or very near peak oil, would the latest oil shock have triggered a merely ordinary recession if our financial house had been in order, or would it have been unusually severe regardless? Second, although GLOBAL oil production has risen enormously over the past four decades, what role did the peaking of U.S. production about 1970 play in the financialization/de-industrialization of the U.S. economy? Did the latter happen precisely because U.S. production had peaked, but global production had not, so that petroleum-fuelled transportation remained relatively inexpensive and permitted intercontinental labor arbitrage?

You were lumbered with a stupid Ideology.

Capitalism.

Capitalism has no moral fiber.

You exported all your skills overseas because of capitalistic logic.

Blind Freddy could see that is was not in your children's interest to abandon the skill needed for survival.

Morals are not an optional extra.

Nor are they cheap.

Spain found gold in South America.

Every Spaniard became a millionaire. They bought all their goods from their neighbors.

And so lost their skills.

Spain went from the powerhouse of Europe, to a pauper state.

So much for their military might and their Armada!

They are showing signs of recovery now, 200 years later.

You can expect the same.

I think this way about the fall of Rome. They had a constant inflation problem, and no one has really figured out why.

Remember... they were importing very significant quantities of wheat from North Africa, and they had a merchant class speculating and forward buying on those harvests.

Large imports and leveraged buying unbalances money.

My model suggests a bit more complex picture (see link below). It is net energy (or exergy) that feeds the economy, not the raw energy (e.g. oil). Because of the declining EROI in all ff energies the net energy appears to peak many years before the expected peak of oil extraction rates. In fact about thirty years +/-. If we anchor the peak of oil production at 2008, that means that net energy from oil, the predominant form for the OECD countries, peaked in 1978 and the economy's ability to do useful work (real goods and services) has been in decline ever since. Save any nominal increases in efficiencies or reductions in wastage (yeah right, that's what SUVs were), our capacity to do work has diminished at an accelerating rate these last thirty years.

The response in the US has been to ship manufacturing and some kinds of service abroad to take advantage of low energy lifestyles and hence lower wage labor. Americans demand higher wages and more costly medical care because we are used to (spoiled is a better word) high energy consumption lifestyles. The import of cheap (plastic) goods to WalMart is another symptom. So what we call globalization may be seen as a long running adjustment to lower energy flows.

Meanwhile, as Gail points out, we Americans and most OECD citizens have shifted to debt financing of purchases with the belief that we would be able to service that debt in the future. That belief is based on our experience with growth in net energy comes expansion and creation of wealth. In the past we always experienced this expansion in the future so we came to expect it would always work that way in the future.

The system was already moribund with the peaking of net energy. Only no one knew it because we don't track net energy, only gross (barrels of oil). Hence people and governments alike grew increasingly dependent on debt and betting on a future that they sadly didn't know would be constricting not expanding. This is also at the base of the creation of many derivative products that are little more than desperate bets on the supposed future. The exotic financial world we see today is nothing more than an illusion that sometime in the future we will grow again and be able to pay it all back with newly created "real" wealth.

What peak oil does is signal that something is wrong. What the spike in oil prices did was act as a trigger that sent a bullet into the already existing bubbles in debt-financed markets. But the build up of those bubbles long preceded the bullet. While many of us have been fretting about peak oil, peak net snuck right past us. We are already hemorrhaging wealth (e.g. infrastructure being let to rust and decay) but it will take time to realize it.

See: Economic Dynamics and the Real Danger

Question Everything

George

When one has to limit the length of the post to 800 words, and is writing for an unknowledgeable audience, one has to do a little simplification. I agree though that peak net energy took place a while ago, and is the problem. And pumping huge amounts of energy into "renewables" with slow paybacks and ultimately low net margins will not make our net energy problem any better--only worse.

Gail, I have a hard time trying to understand your thinking on this matter.

In the future when we really have very little easily accessible fossil fuel energy would you like to have access to some renewable energy or no energy at all? If you'd like to have some then don't you think you had better invest what is still relatively cheap fossil fuel energy to help put in place the infrastructure that you will need to be able to harness the renewables.

How exactly will doing this make our net energy problem worse when the alternative is to continue as we are until our net energy is going to be zero, or worse negative?

So when the 500 lights in your crystal chandelier finally do go out would you prefer a very expensive solar powered LED flashlight that has been paid for with non renewable energy but at least you have it in your hand, or a cheap kerosene lantern but no kerosene? I guess at that point you could burn the furniture for a few days.

I don't see wind as lasting any longer than fossil fuels. It just replaces some of the fuel our current system uses, with the hope that this will make the whole system last longer. You need to have the whole system up--transmission lines, natural gas (or some other type of back up), besides the wind turbines themselves. You also need roads in good repair for servicing the wind turbines, and for maintaining the transmission lines--helicopters, to get to the difficult to reach places. You also need our current system of world trade supporting the whole system, so that replacement parts can be obtained when needed.

Most of the solar is grid-tied. If the grid goes down, these homes will have daytime electricity for several years. That is fine, but not worth nearly as much as say, having electricity at night, or so that a refrigerator or an internet server can stay operating 24/7.

Having LED flashlights and the like depends on having batteries that work. Batteries are short lived, so even if you have the renewable energy, the batteries are a limiting factor.

Yes, I agree that example was more of a metaphor than an actual plan for the future.

Well that is still true today, though my own clientele is tending towards completely off grid systems using tried and true lead acid battery backup. You can run your refrigeration and computers 24/7 on these systems.

That is a description of BAU. I agree 100% that that will not be able to be maintained by any alternative or renewable energy. However I think that the point is we will be living in a very different world than the one you describe. The point is not to try to make the current system last longer at all because we already know that we can't and won't be able to do that.

It's time to start thinking about a completely new paradigm on all levels. I have no doubt that wind and solar will continue to play an ever increasing role in this new paradigm and as far as wind is concerned we have been harnessing it since the dawn of civilization and I'm sure that if humans are still around, we will still be harnessing it long after the age of oil is completely dead. Perhaps you should try sailing a small boat out onto the ocean to get a feel for what the new paradigm might be like. I highly recommend the experience and a lot can be learned from it.

Any energy production technology will need to produce not only the energy needed by society but enough excess energy (that can be used somehow) to take the place of the fossil fuel subsidies currently being used to support it. We currently use fossil fuels to produce wind and solar systems. When the FFs are too expensive will wind and solar provide enough extra power to run the factories that produce them, provide the road maintenance, produce spare parts for maintenance, provide power to extract raw materials or recycle old material? That is the key to true sustainability. These systems have to be able to support themselves to achieve it.

One of the reasons I feel it is terribly important to establish the true, wide-boundary EROI for these systems is so that we can answer those questions. Even if, after all the energy investments are taken into account, the wide-boundary EROI is just marginally greater than 1:1 it might be worth doing, esp. if we as a society are ready to dramatically reduce our energy consumption. The problem is we don't actually know the true EROIs for each unit of usable energy produced by any of these actually is (we don't really know it for oil either, all we know is that it started really high which is what leveraged us into the industrial age). So we don't know if in the end we will experience a net energy loss (EROI < 1) or not. And, don't forget that all of this assumes we actually do have the energy and materials available to scale up while we still have oil. I'm beginning to seriously doubt that. We're already into hock up to our knees because the net energy peak and decline is taking us down.

Perhaps you should try to work out in more detail what you envision this new paradigm actually looking like and how it will work. We have all taken so much for granted vis a vis the availability of cheap FF that it is hard to see, sometimes, the degree to which all of our asset production assumptions (building that sail boat) are derived from that fact. Take away the FFs, which is exactly what is going to happen, and you are left with a unimaginably huge gap between even our so-called basic consumption needs and what alternatives can supply anytime soon.

You are right of course!

I have been trying to come to grips with the details of the the new paradigm that I envision. Most of the time I am reluctant to articulate my vision because of the constant push back from people who are unable to envision anything other than BAU. It really gets old very fast.

Though much of it has already been proposed by the people who are working on things like transition towns, permaculture, alternative currencies etc... Some right here on the Oil drum, Jason Bradford comes to mind. Some of the ideas from comenters such as AlanfromBigEasy.

The ideas from the people at the Post Carbon institute such as Richard Heinberg. Or people like aangle from http://www.postpeakliving.com

There are ideas like those of architect Simon Velez of Zeri Pavillion fame, BTW sailboats can be built from similar materials using similar construction techniques. My list goes on and on.

To be honest I think there are many bits and pieces of the puzzle of what the new paradigm will look like that will continue to emerge as time goes by. What we need is more people who are willing to let go of the known and make the leap into the unknown.

In any case you have given me a bit of an incentive to come up with a clearer articulation of my vision. I will try to put some of my ideas down on paper (computer screen) and present them for discussion.

This problem is called 'the paradox of production' and was explained well some years ago on EB (Energy Bulletin).

I think the Energy Bulletin post you are talking about is one by John Michael Greer called The Paradox of Production. It talks about the huge demand on existing fuels, when one wants to build a whole new infrastructure of a different kind. It says:

It seems to me that you really have to have some means to pay for the fuel to drive up energy costs, though. If the primary way of getting money is taxes, and sources have pretty well dried up, then it won't be possible to pay for the new infrastructure. The lack of debt availability will make the situation worse too. So it is hard to see alternatives being scaled up.

I think I'd want to see more than just a qualitative graph before I'd be persuaded that EROI was already so low on the whole as to have pushed the net peak back by 30 years. The effect isn't linear in the EROI number; if EROI drops from infinity to 20, that's only a 5% relative loss in net energy, or a year's growth back when things were growing robustly, or a small enough effect to be buried in the noise. The real trouble sets in as the number approaches unity, as for corn ethanol.

Thick me. I'm having trouble parsing your words to understand the meaning. You seem to be implying that I jiggled the EROI to move the peak of net back. That isn't the way it works. No matter what the energy cost curve the phase shift of peaks is just about the same. All that is effected with lower costs is the net amplitude is closer to the gross. Of course, if costs were zero then net would equal gross and there wouldn't be any problem.

The model is theoretical but based on physical laws rather than curve fitting on the upside and assumptions about symmetry on the down side. Not sure what you mean by conceptual. Full paper in process.

No, not suggesting manipulation of the EROI at all. Just that a drop in EROI from 100 to 10 would have a similar effect to a drop from 10 to 5, so at the large numbers, a large numerical drop doesn't make much difference to the overall economy. OTOH, a drop of just "1", from 2 to 1, puts things out of business. I'm wondering how low the number can go before there's a real problem.

I'm also really questioning whether we can claim EROI has pushed the peak back 30 years, i.e. from the late 2000's to the late 1970s, which doesn't seem to be reconcilable with the apparent visible reality that since then, there has been a huge increase in a variety of activities, such as car-driving, as well as a huge increase in oil production. Intuitively it seems as though one might need a drop in EROI from effectively infinite (negligible energy cost of producing energy) back then, to substantially less than 2 now (to burn up the entire increase in gross energy production and then some, on the basis that total net energy is not only lower now than then, but so much lower that the peak is not in between.) That just doesn't seem credible (except maybe at the margins tar-sands and ethanol) without quantitative graphs.

Sorry, but I continue to find it hard to get your point.

My model is based on the physics of energy extraction from a fixed, finite reservoir where something dynamic systems modelers call "backpressure" (increasing negative feedback as the system matures) develops over the extraction period. Another aspect of this is the "best-first principle" whereby the early extraction is of the low hanging fruit and later extraction (including finding) gets harder and harder. The hardness is reflected in the energy cost required to extract the next unit of energy from that reservoir. I suppose this is what you mean by qualitative, but others would say it is a model based on first principles.

The energy costs increase as it gets harder to extract. Pretty simple actually. What this results in is a decline in EROI. I basically understand your argument about the ratios but it is irrelevant since the model deals with actual costs not EROI as such.

I suppose it depends entirely on what you mean by huge increase in activities. Sure the financial markets have boomed. The housing market was in an incredible and unrealistic bubble. As for manufacturing in the US, that moved elsewhere. Why? To compensate for the American high-energy demand lifestyle reflected in higher wages. Substitute Chinese labor that has much lower energy requirements for their lifestyle and also replacing some machine-based processes here, and you will soon see that the activity simply shifted to a more agriculture/labor (and lower power requirement) form.

Americans, and most OECD economies, have been living under an illusion of economic growth (based on values of GDP which is a bogus measure) by substituting debt for production of real wealth. For the last thirty years we have been keeping the illusion alive by borrowing to bet on a future that will never arrive. If that is what you meant by increased activity then you are suffering from the same illusion as the majority of others. Meanwhile our infrastructure has decayed. We can no longer muster the resources to tackle important issues like global warming without borrowing from Chinese savings.

If energy costs for extraction were zero, then the peak of net energy would be exactly the same as peak gross flow (peak oil). But that isn't the case. As you increase the costs (declining EROI) both the phase relation and the amplitude of the net curve change. The net peaks before gross. Very simple. By what time frame depends on the growth rate of energy costs, not the abstract EROI ratio per se. A thirty year phase shift is an educated guess, but it is based on the best estimates of costs we have at present.

What does peak oil signal? That depends. It can signal that:

1. Crude oil resources depleting

2. Crude oil producers cannot pump more (technical problems) or are unwilling to do so (political issues, economic strategies)

3. Demand is less than production and thus producers are forced to produce less.

When one says that crude oil production peaked in 2008 is it due to point 1 or due to point 3? In future it well may be that diminishing production is due to points 1 and 2.

You may have missed the point re: net energy peak timing.

To oil analysts, all the world's an ... oil drum. But Ilargi didn't say the sources of trouble were mutually exclusive, and we know very well they rarely are. That post was on "driving force", which IME boils down to the societal "we" in North America and Europe making far vaster promises than could ever be carried out even with abundant oil at $20.

It was a real Rube Goldberg machine. For years, people with negligible earning power flipped houses at each other until finally many became notional millionaires. Once they felt like millionaires, they felt egotistically entitled to live as millionaires. Since they never had the skills or the get-up-and-go to earn that status, they used the houses as free-money machines. That put a call on the goods and services they had never produced (nor could ever have produced.) That in turn led to the Wile E. Coyote moment, and the problem was suddenly exposed.

It's simply easiest for both individual citizens and politicians to live extravagantly and put it all on the never-never, rather than ever say "no". This is hardly a new problem; indeed it long predates fossil fuels and the industrial era. Gluttony was after all one of the traditional "seven deadly sins".

Now, did scarcer oil help push the tottering edifice over? Very possibly.

I agree with you Gail, the more I read the AE the more I question the analysis of their stuff. There appears to be a certainty in their prognostications that they don't support.

David Strahan in his book the The Last Oil Shock devotes a chapter (5 page 115 on) to just this problem and cites several academics who appear to provide a convincing argument as to the underestimation of energy cost and economic activity. Other references such as The Coming Economic Collapse: How We Can Thrive When Oil Costs $200 a Barrel, Stephen Leeb also cites work which shows a correlation between energy prices and economic recession.

FWIW, I do believe the current economics is a ponzi scheme, but energy prices seem to be the fuel and high energy prices the lighter for this economic meltdown. Decoupling a complex system to give definitive concrete answers seems doesn't seem possible, it would be good if the language in AE had a tone more conducive for questioning the areas of uncertainty.

It seems once Illargi is convinced of a conclusion he is little inclined to entertain other possibilities and can become quite belligerent in the process, so it's likely you'll gain little in this debate.

To me, Matt had it dead on here because what we experienced in Sept 2008 was exactly this, a seizure of the credit markets.

This thought was echoed here as well:

So to me it's obvious the 8 year run up in oil prices culminating in $147/barrel oil was the direct cause of that seizure.

I don't agree. Alan Greenspan has now revealed that easy money from 2002 to 2005 was specifically intended to counter threats from the Mideast, which he considered very real. And what comes to mind when we think of the Mideast? - oil. In other words, he wanted to buildup the economy against the threat of oil supplies from the Mideast not being secure.

So oil is exactly the reason why the financial bubble developed, and alternative explanations in this case are simply wrong.

We get lots of explanations--some match reality, some don't. The recession is pretty much a world-wide phenomena. That Alan Greenspan did or didn't do is only a small part of the total, and not an answer to where we are now. Without peak oil, the bubble could perhaps have gone on longer, and been replaced by another bubble.

Gail,

CSPAN Book Review just did a show on Nicole Gelinas's book: "After the Fall".

Here's a link to a video clip: After the Fall

Author Gelinas provides an impressive, whole other view of what got us to where we are today.

Perhaps so, I don't recall running across that revelation; it would be interesting to see substantiation, a link. If it's true, maybe Greenspan was entering senility, which is not altogether uncommon at his then-age. After all, I'm finding it hard to see how adding vast tracts of gargantuan houses to far-flung oil-guzzling suburbs - which is mainly what the easy money accomplished - was supposed to counter a threat to oil supplies, irrespective of whether it can or cannot be said to have built up the economy in some other respect.

You´re probably right, but is that relevant? Surely the whole point to a peak oil blog is that it is assumed to be on-the-topic as far as our future prosperity is concerned. Consider the recently re-subtitled Early Warning (Risks to Global Civilization), another oil blog, for example. If the immediate risk to our global civilization is not peak oil, but a debt implosion, even if it was originally caused by peak oil, who is on-the-topic, you or Ilargi? Sounds like we´re all going to be debt-buggered long before we´re oil-buggered.

My old dad, now sadly deceased, called that ¨picking the fly-shit out of the pepper¨ which I always took to mean trying to figure out what was relevant. Is that why Ilargi left Oil Drum, he figured out that peak oil is true, but not relevant?

I do not know all of the reasons behind while Ilargi left, but I am sure that there were other reasons that were much more important.

Given that you are an actuary, you of all people should understand that our "financial" systems are at their core, just people taking on present-day legal obligations (a fancy word for making promises) with the assumptions --many such assumptions-- that the promissors can and will be able able to fulfill their obligations at a later date.

IMHO, many of the discussions in this thread jump the gun by assuming that the only question is one of a sliding scale between Price of energy ($$/BTU) and resulting profit (a.k.a. returned interest, ROI, $$Out/$$Input) from undertaken business ventures.

But before we get to that space, we first have to solve the binary Yes/No (1/0) questions regarding whether certain transactions can go forward at all (Yes/No) rather than at what price. It is there, I submit, that the seeds of "collapse" emerge.

_________

I realize I've gone too abstract here. So allow me to step back and give a hypothetical example:

Suppose a large company decides to build its new new company headquarters in a downtown area --say, San Francisco.

Suppose they plan for a certain number of low-wage but high skilled employees (e.g., IT people) to show up at that building. Without them the enterprise fails.

Suppose that there is a pool of low-wage/high skilled employees, but they live far away (East Bay) and can't afford high rents inside the city. The only practical way for these employees to get to the city is with electrified rail (for example the BART system in the San Francisco Bay Area).

Everything is going fine until one day, a small plane crashes into the high voltage towers that feed the train system and the Black Swan event takes out the electrical power (or worse yet a major earthquake hits, or a big storm). Due to financial weakness, the utility cannot repair the electrical lines anymore. Maybe in 3 months time, but not now. Say for example, repair contractors are no longer accepting IOU's signed by the Goobernator, Mr. Schwarzenegger and the repairmen simply refuse to do the work. In that case, the trains stop running. It's a Yes/No situation; not a how much money situation. And then the company headquarters fails. That too is a yes/no situation. One domino topples and then the next and the next.