Trade, Transportation, and the Chinese Finger Trap

Posted by nate hagens on December 29, 2009 - 10:14am

(This essay originally ran three years ago but the concepts and implications remain relevant today. )

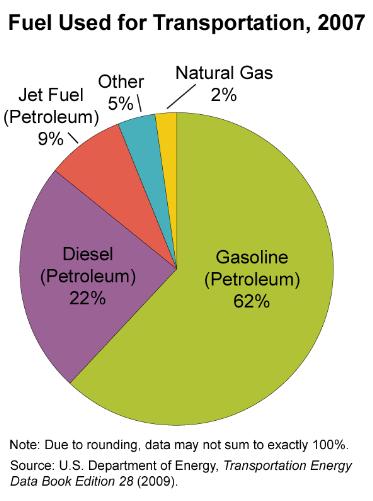

One of the central underpinnings of neo-classical economics is trade. And one of the central tenets of trade is the Ricardian theory of comparative advantage. Trade (in theory) benefits both parties because both are better off after the exchange. But our international trade system has, by baby steps, become completely dependent on twin enablers: crude oil and credit. By air, water, land or rail, petroleum accounts for 95% of all transportation energy. As we move up the complexity chain in the products that make up our daily lives, are we moving further into a Chinese finger trap where there is no backing out?

This post will examine the theory of international trade and the hierarchy of goods transport, production and consumption. It is quite possible that in the next decade, the increase in price (or the decreasing availability) of oil and financing, will offset the benefits of many types of trade.

The pursuit of economic efficiency, through increasingly diverse and extensive global trade has glossed over two important facts which this post will examine: 1) higher oil prices in long distance transport must at some point exceed (economically or otherwise) the benefits achieved from some trade and 2) a complex global trade system is gradually but pervasively decreasing the ability for localities, regions and nations to be self sufficient – so many of our supply chain inputs are imported that continued increase in oil price/affordability will resurrect import substitution policies, not only for less developed countries, but for the US and rich nations as well.

International Trade - A Chinese Finger Trap?

INTRODUCTION

The idea for this post originated on a recent errand to Fleet Farm to buy a replacement spark plug for my dad's chain saw. I discovered there are not one or two kinds of spark plugs but hundreds, depending on the type of machine they go into. The plugs were made by a variety of companies, some domestic, some foreign but none from my state (currently Wisconsin). As I noticed this, I looked around the dozens of aisles and hundreds of shelves at the thousands of products and 'saw' for the first time how complex our import/export system has become. And the fact that my dad couldn't cut our firewood without that certain sparkplug reminded me of Liebigs law of the minimum, or in the vernacular - something is only as good as its weakest link. I couldnt help wondering how much oil was embodied in those spark plugs: their parts, their manufacturing, their delivery to central Wisconsin, etc. While my research didn't discover this answer, it did result in my viewing trade, transportation, and our society's consumption habits in a different light.

Much has been written on this site and elsewhere on the exact date or time range when we begin the second half of the age of oil. I will not address timing in this post other than to point out that the later it is, the more can be done to address the systemic risks suggested below. The human pendulum of complacency and panic is in full effect as oil breached $50 on the downside today. Those who read this piece and connect the dots should recognize that $50 oil is not a reflection of its abundance or scarcity but is rather an opportunity to effect change (because change is cheaper). There are after all, about 30 billion barrels less oil left than there were a year ago.

Finally, though the following analysis may suggest otherwise, I am not against free trade. I think trading is fundamentally human and improves peoples lives. The theory of comparative advantage was one of the coolest principles I learned in graduate school. But the giant extended tentacles of free trade are one of many premises that were initiated on an empty planet that may require contraction/adjustment on a full one.

TRADE

Trade has been around almost as long as humankind. Historically trade was largely a barter system, before currency was adopted as a medium of exchange. Modern international trade is based largely on Ricardian model of comparative advantage, one of the most eloquent but non-intuitive concepts in economics. Indeed, a story told amongst economists is that when an economics skeptic asked Paul Samuelson (a Nobel laureate in economics) to provide a single, meaningful and non-trivial result from the economics discipline, Samuelson quickly responded with "comparative advantage."

ABSOLUTE AND COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

The early logic that free trade could be advantageous for countries was based on the concept of absolute advantages in production. Adam Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations:

"If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage. " (Book IV, Section ii, 12)

The idea here is simple and intuitive. If one country can produce some set of goods at lower cost than a foreign country, and if the foreign country can produce some other set of goods at a lower cost than can be done locally, then clearly it would be best to trade for the relatively cheaper goods of both countries (or regions). In this way both parties gain from trade.

If a person/region/country can make a product cheaper or more efficiently than someone else, they have an absolute advantage in this product. However, a country that can produce two things (or everything) better than another country can still benefit from trade. This is due to the brilliant (on an empty planet) theory of comparative advantage first articulated by David Ricardo. Here is an example:

The Magic of Comparative Advantage – A Hypothetical Example

Both Wisconsin and North Carolina have lots of trees, productive farmland, access to labor, and cows. (assume for this example their labor force and populations are equal) Both produce cheese and furniture. But Wisconsin (for various reasons) has an absolute advantage in the ability to produce both cheese and furniture. If they were to devote all their resources each laborer could produce 12 units of cheese or 4 units of furniture. In North Carolina, each unit of labor can produce 6 units of cheese or 3 units of furniture.

Wisconsin is 'better' at making both products, but applying the theory of comparative advantage, North Carolina is ‘less worse’ at producing furniture. This can be seen via the concept of opportunity cost. For every unit of furniture production, NC is giving up 2 units of cheese production (6/3). For every unit of furniture production in Wisconsin, they are giving up 3 units of cheese production (12/4). Therefore it is ‘more costly’ in terms of opportunity lost for Wisconsin to produce furniture than it is for North Carolina, in a world of frictionless trade.

Specifically, in a position of autarky (or closed economy), each state will devote half its resources to each production pursuit – Wisconsin will produce 6 units of cheese and 2 units of furniture. North Carolina will produce 3 units of cheese and 1.5 units of furniture. In our hypothetical world without trade then, a total of 9 units of cheese and 3.5 units of furniture are produced.

But then a trade agreement is signed. Because they have a comparative advantage in furniture, North Carolina devotes 100% of their resources towards producing 3 units of furniture. (and no cheese). Wisconsin produces 12 units of cheese (and no furniture). Now the ‘world’ has 12 units of cheese and 3 units of furniture. However, Wisconsin can easily shift 3 units of its cheese production to create one unit of furniture. The world now has 9 units of cheese and 4.5 units of furniture with no extra resources or labor.

Trade, via specialization, has magically created an extra piece of furniture, with still the same amount of cheese!

WHAT PRICE CHEESE?

A key question in this post: what happens when the cost of transportation of cheese and furniture between North Carolina and Wisconsin (via higher oil prices) exceeds the benefits from trade (an extra unit of furniture)?

I remember in graduate school thinking comparative advantage was pretty cool. But, like many things in neo-classical economics, comparative advantage relies on a battery of assumptions, many of which prove problematic in the real world. Josh Farley and Herman Daly succinctly describe some criticisms of the assumptions that underpin comparative advantage in their textbook "Ecological Economics"(1),

1. "No extra resources" simply means no additional labor or capital - there IS commensurate resource depletion and pollution accompanying the extra production.

2. The neglection of transportation costs. Transportation is energy intensive, and currently energy is not only directly subsidized, but, in addition, many of its external costs are not internalized in its price. Consequently, international trade is indirectly subsidized by energy prices that are below the true cost of energy.

3. There are two important costs of specialization. First, all cheese makers (cheesesmiths?) in North Carolina must become furniture producers and vice versa for furniture makers in Wisconsin. Making such a shift is costly to all whose livelihood is changed. Also in the future the range of choice of occupation has been reduced from two to one - likely a welfare loss and assuredly an occupational risk.

Furthermore, after specialization, countries lose their freedom not to trade (the chinese finger trap). They have become vitally dependent on each other. . . Remember that the fundamental condition for trade to be mutually beneficial is that it be voluntary. The voluntariness of 'free trade' is compromised by the interdependence resulting from specialization. Interdependent countries are no longer free NOT to trade and it is precisely the freedom not to trade that was the original guarantee of mutual benefits of trade in the first place.(1)

CAPITAL MOBILITY

An often overlooked provision of Ricardian comparative advantage, but one of extreme relevance in today's world, is that of factor immobility (factors other than cheese and furniture). In reality, today's borders are porous to billions upon billions of dollars of capital movements moving to the areas of the world with the cheapest production. In effect, the rich countries have a comparative advantage in 'money' and are trading it for the labor and resources of other countries.

A country's current account is the difference between the monetary value of exported and imported goods and services. When the imports are greater than the exports, the account is in deficit. If exports are greater, the current account is in surplus. So, comparative advantage, with the assumption of immobile factors relaxed has effectively resulted in the erasure of national boundaries for economic purposes.

Some people call this globalization.

The following graph shows the increasing percentage that trade is out of total US GDP:

US International Trade as % of GDP- Source US Census Bureau Click to Enlarge

Below is a chart of US imports and exports and our trade balance:

US Imports and Exports - Click to Enlarge

As can be seen above, imports have been outpacing exports for some time and the pace has accelerated of late.

Though the basic goods vs luxuries trade mix is a complicated analysis, one thing is clear - oil now makes up 10% of the dollar value of our imports:

US Oil Imports by Country - Click to Enlarge.

Finally, it is of some concern that 'services' continue to increase as a percentage of our national ledger (implying that 'goods' are becoming less). We still do produce huge amounts of food for export, but that is increasingly being accompanied by movies, massages and things higher up the 'discretionary' hierarchy (more on that below). Here is a graph indicating the growth of services vs goods in our Gross Domestic Product and Employment. America seems to have a comparative advantage in 'services'. The counter-argument is that more services naturally arise as economies become less energy intensive - this view ignores energy as a unique input, and therefore all countries can't become less energy intensive over time under a growth regime.

US Goods and Services- Click to Enlarge.

THE GRAVITY MODEL OF TRADE

The Ricardian model is not the only economic model dealing with trade. The Gravity model of trade gets more at the heart of this post - that of the relationship between trade and transportation. It presents a more empirical analysis of trading patterns rather than the more theoretical models discussed above. The gravity model, in its basic form, predicts trade based on the distance between countries and the interaction of the countries' economic sizes. The model mimics the Newtonian law of gravity which also considers distance and physical size between two objects.

Gravity Model of Trade-Commodity Flow Correlation with Distance (2)- Click to Enlarge.

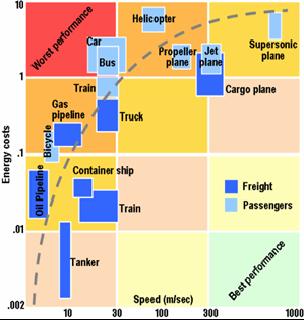

Here is another graphical illustration which incorporates speed (which increases energy return on time) and energy intensity:

Energy costs vs speed

Jean-Paul Rodrigue Hofstra University (hat tip H.K.)

It makes sense that trade is inversely correlated with distance because even at today's cheap oil prices (remember - oil is cheaper than water, milk, orange juice, YooHoo, etc), things cost more to ship further. As oil prices increase, this inverse correlation should strengthen.

A PALEO-ECONOMIC PALATE CLEANSING SIDEBAR BEFORE WE MOVE TO TRANSPORTATION

A recent article in the Economist points out that comparative advantage also works at our most basic level of trade (male/female) and was of historical significance:

In existing pre-agricultural societies there is, famously, a division of food-acquiring labour between men, who hunt, and women, who gather. And in a paper just published in Current Anthropology, Steven Kuhn and Mary Stiner of the University of Arizona propose that this division of labour happened early in the species' history, and that it is what enabled modern humans to expand their population at the expense of Neanderthals.

With Peak Oil likely being in 2005, perhaps I should brush up on my woodchopping and carcass dragging skills...;-)

TRANSPORTATION

Our modern society is structured around just-in-time delivery of people and things. And petroleum makes up the vast majority of getting things around. Fuel represents 35% of operating expenses for airlines; the direct fuel cost is 20-40% of the total cost of trucking and fuel costs amount to 20-30% of cost for sea freight. And transportation itself comprises an increasing amount of total energy use:

Transportation as percentage of total energy use- Click to Enlarge

In the 1960s transportation accounted for about 23% of all energy expended in the USA- now the figure is approaching 28%. The yellow line (almost on top of the pink line) shows that of the transportation, 99% of it is oil (there is some electrical, natural gas and coal usage) (3). We are really dependent on oil!

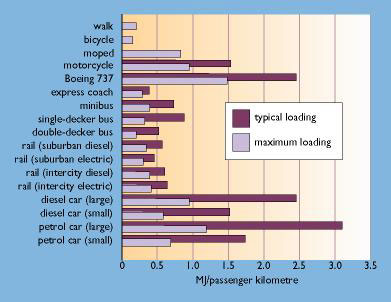

The following two graphs show the energy efficiencies of various modes of transportation first for people and then for goods. This first graph is from Richard Heinberg's book "The Oil Depletion Protocol" and is based on data from Britain (which Richard tells me is fairly universal):

MegaJoules per passenger- Click to Enlarge

As can be seen, the bicycle is the most energy efficient mode of transportation - even better than walking. The other insight from the graph is we gain quite a bit of efficiency from packing a lot in one vehicle. (This is a concept used often in China.)

As far as transporting goods, there is a large disparity in energy efficiency per ton mile for different transport methods:

Energy Intensity per ton mile by freight mode. Source - EIA Click to Enlarge

The above graph is somewhat dated (1991). Though there have been efficiency improvements across the board, the general model of water/rail/truck/air in order of efficiency seems to still be intuitively correct, though some argue that rail is more efficient than water. It is actually quite a complicated issue as it depends what one is transporting and the sequence of steps. Alan Drake recently did a study showing rail transport to be 8.3 times as efficient as trucking.

One can visualize the energy efficiency/footprint of various transportation modes as something like this pyramid:

The Transportation Pyramid. Click to Enlarge

As transportation costs increase, communities and regions that are able to effect movement downwards on the pyramid towards its base will have comparative advantages, due to savings on energy costs, and availability of products.

ENERGY USE AND HUMAN WANTS AND NEEDS

Let's now shift gears just a bit. Psychologist Abraham Maslow theorized that humans meet basic needs in a hierarchical fashion. Once basic needs are met, we seek to satisfy higher needs such as self actualization and fulfillment. In the current era of cheap oil, at least for western society, a very small percentage of energy is spent on basic needs compared to the energy intensive 'desires' that drive western society:

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs------------------Nate's Intuitive but Made Up Hierarchy of Energy Use. Click to Enlarge

This concept can be expanded upon. We sometimes take for granted the things that we really need, and make us happy - I am 90% as happy eating fried fish from a local lake as I am driving to Chicago to my favorite sushi restaurant (well at least 80%). Higher personal consumption efficiencies in an energy challenged world are lower on the pyramid.

The Consumption Pyramid - Click to Enlarge

We finally come full circle to the spark plug question. There is a great movement (at least in the peak oil circles, not yet in the peak credit circles) towards relocalization. But 'local' labels in many cases are misleading due to the insidious reliance on foreign parts at different moments in the supply chain.

One of my best and oldest friends is an entrepreneur from China. He owns a business in Connecticut that seeks out American companies that need nails, screws, and small metal parts at their factories - he then signs contracts for 5 million screws at 2.5 cents each - screws that in the US would cost 6 or 7 cents due to higher labor etc. He pockets half the difference--the point being that our basic goods might ostensibly be made here, but their component parts may not.

I have not seen a way to measure this so have come up with my own "Embedded Transportation Chain". First Order Origin represents where you buy something (in your town would be 100% local). Second Order Origin represents where the components and parts came from on the product you bought. And Third Order Origin represents where the raw materials came from for the parts to make the Second Order Origin parts. To determine how 'local' (in the sustainability and security sense) a product is, one would multiply Level 1 * Level 2 * Level 3. Of course, there is very little that is truly local, as a world of increasing international trade has increased 'Third Order Origin' percentages dramatically. (I don’t have accessible data on this-the amount of work would be closer to an academic paper – here I just wanted to lay out the idea). True to the field of economics, I have made these terms up. However, also consistent with economics, one can grasp the common sense implications. When looked at in this 3-tiered light, the phrase “Made in America”, takes on different meaning.

The Transportation Origin Chain- Click to Enlarge

I currently reside in Wisconsin. To eat local is cheese curds, fried fish and venison. All these things can be bought (or harvested) locally. But the cheese company gets milk transported from around the state, and uses packaging made overseas from natural gas. Its employees drive to work using cars made in Japan and oil from Nigeria and eat food imported from New Zealand. Although the dairy farmers themselves use largely local inputs for feed and bedding, their milk buckets are made from steel processed in China, and the wood for the barn comes from a mill in Canada. It is not easy to decipher the ‘localness’ of a product, unless one walks out and picks a wild mushroom. Use your imagination however to consider WHAT IF oil doubles triples or more in price, what sort of domino effects might occur in the production supply lines. It is hard to predict what "Liebigs product of the month" might disappear from the store shelves - Charmin bath tissue one week and Stihl chain saw blades the next.

A quick example is footwear. 98% of all shoes in the United States are made somewhere else, many in China.

CONCLUSIONS

Increases in efficiency of goods production in a global context are considered a good thing, as they raise respective countries GDP, and allocate resources wherefore the total pie gets bigger. Once on this track, however, participants continue to strive for more and more efficiency, more trade advantage and cheaper production. If taken to its natural extreme, every place on earth will specialize to the maximum profit of corporations. Implicit in this path is the forgoing of expertise and local resources that are lower down the pyramid of human necessities. If transport costs are 20% of a products value and oil doubles or triples, they become upwards of 50% of a products cost. Certain products then become uneconomic to ship. Some of those products are components of larger products which do not have local substitutes.

High quality and abundant oil has obfuscated the difference between wants and needs. At a Walmart or a Safeway, young people today see quilted bathroom tissue, pork chops, colorful shoes, dental floss, and avocados as a natural smorgasbord, without internalizing the complex energy/trade chain that put them there. This plethora of choices that globalization offers us could just not be possible in local or regionally based economies. In some sense, to revert the global network of specialization back towards less complex, more regional networks is kind of a chicken-or-the-egg dilemma. Unless we change the consumption drivers, there will be little incentive for the manufacturers of nascar lunch boxes to move downwards the production/transport and global/local pyramids.

When (and in my opinion, it's only a matter of when) oil becomes less available/affordable, centralized forms of energy command will not be efficient because different regional blocks and localities possess their own comparative energy and resource advantages and disadvantages. National umbrella energy policies treat all states the same. Corn ethanol roll out is a prime example - what might be great for communities in Iowa and Minnesota has different math for California and Vermont. We know that distance impacts energy efficiency and costs. We also know that different states (and countries) have different indigenous energy resources (Quebec has hydro – Arizona has sun, Montana has wind and coal, etc). It is likely there will be decentralization of energy production as regions move toward building blocks of basic needs in safer spatial scales. The magic of comparative advantage can still work in the second half of oil. But it ultimately will differentiate between basic needs and unnecessary desires - and take advantage of water and railway access.

THE BOTTOM LINE

1. We need oil for more than just driving. It is embedded in almost everything. Unless you're Amish, Aleutian, or have alot of friends, oil is life in the USA (at least currently).

2. Higher oil prices combined with lower credit availability will eventually make certain types of trade prohibitive.

3. Those nations, regions, communities and families that produce lower on the left graph and consume lower on the right graph will have an advantage when transportation costs increase. Those communities using predominantly rail and water transport will have advantages over those more dependent on truck and air, everything else being equal.

4. As is occurring in some South American nations currently (Peru and Venezuela come to mind), a return to the import substitution model away from the so-called Washington consensus seems inevitable. However, remember the supply/demand wedges in the Hirsch/Bezdek report showing how rapidly production shortfalls could occur. Local, regional and national action needs to be taken soon because of the required long lead times.

5. In rich nations, in addition to conserving, it will be advantageous to begin to be happier with 'less' because the delta of 'desires' may change more slowly than that of 'things' available in the future, relative to other countries (e.g. Europe and Africa) that exhibit lower energy footprints. In other words, though the USA can easily get by with half as much energy-intensive stuff and conveniences, an abrupt change to this level will be much more mentally painful than a gradual one.

In conclusion, as a thought experiment, the next time you go to your nearest box store, look at the gazillion products on display. Try to imagine where they come from, where their parts come from, and how that supply chain might change when new oil production fails to match decline rates of older wells. While you are there, you might notice how many of the myriad products improve the lives of you or your friends, and how many do not. This 'demand' side view of Peak Oil will be the subject of my next post.

Next post (if I successfully defer my addictions): "Evolution, Discount Rates and Addiction"

Nathan John Hagens

theoildrum.com

email thelastsasquatch@yahoo.com [2009 e-mail njhagens at gmail dot com]

Resources cited:

(1) Ecological Economics - Principles and Applications, Herman Daly and Joshua Farley (in my opinion, a textbook that should be used in every college in America)

(2) "Gravity for Beginners" Keith Head. http://pacific.commerce.ubc.ca/keith/gravity.pdf (.pdf warning)

(3) National Transportation Statistics 2006(pdf warning), US Department of Transportation

Note 12/28/2009 - I intended to update this analysis with a) statistics on fuel cost/intensity relative to cargo value/necessity, and b) the transport substitutions that may become available for oil, but other projects became more pressing (read: interesting). Also, though I mentioned credit in the essay, many of the advantages of trade may disappear even with plenty of oil, if significant currency reform/reset occurs or if credit becomes generally unavailable. If anyone has expertise in those areas they'd like to share as a guest post, please submit an abstract, or summarize in comment section below.

Thanks, Nate!

This post was long enough ago that I didn't remember it. Clearly whether we can maintain international trade is a huge issue. Either high oil prices or credit problems (or a combination) could disrupt trade.

One thing that strikes me is that international trade enables a huge number of products that could not be made in any one single location. Where could we make computers without international trade? These products would likely go away, without the inputs required.

The other thing that strikes me is that boundaries make a huge difference in figuring which type of transportation is most efficient. Bicycles are more efficient than walking, in some analyses. But walking can be done without any roads, or any manufacturing plants, or any iron mines or rubber imported from many miles away. If one assumes that one would have to build special bicycle paths for bicycles, and set up systems of international trade to keep bicycle manufacturing going, I am less certain it would be "most efficient". It might be more efficient that railroads and airplanes, for example, but it would likely be less efficient than walking.

Underlying the principle of comparative advantage is the principle of specialization and division of labor. Adam Smith built his book around this, it is THE main reason for the Wealth of Nations - or for that of households or individuals, for that matter. Tainter's increased societal "complexity" can be understood in terms of Smith's increasing "specialization" and division of labor. The more labor specializes and divides, the more complex a society can be, and the more wealthy it can be. Diminish labor specialization and division, and you diminish societal complexity, and you diminish the wealth that the society can produce and sustain.

This is the one thing that really gives me pause about the whole "self-sufficiency" idea. Inherent in the idea of "self-sufficiency" is the abnegation of labor specialization and division. "Don't depend on anyone else for anything, do it all yourself." That would seem to me to be a formula that must necessarilly and inevitably lead to poverty, eventually even to abject poverty and destitution.

On the other hand, most of us would agree that present levels of societal complexity, and of the extreme labor specialization and division that undergird them, have been made possible only through the subsidy of cheap, but depleting, FFs, and thus are not sustainable for much longer. Some unwinding of societal complexity, some unwinding of labor specialization and division, and thus some decline in levels of wealth and income, are therefore inevitable and necessary for society to transition to something that is sustainable solely by renewable resources. This is not the same thing as saying that all labor specialization and division must therefore come to an end, however. For many thousands of years, traditional cultures that were operating only with renewable resources and thus were essentially sustainable nevertheless had a considerable amount of labor specialization and division. Each settlement would have its black smith and an array of other trades and crafts people. Some farmers would specialize in certain crops or livestock. Given that we had not one but many societies operating around the globe for many thousands of years on that basis, I see no reason why we cannot level off at something that at least returns us to that pattern, more or less. (And yes, I know that the global population is larger now; I suspect that it will decline in any case, one way or another, until it gets down to something that can operate societies like what I described on a sustainable basis.)

The question is: how much must be give up, and what might we hope to keep? Is it possible to still make bicycles, to continue with Gail's example?

It must be noted that bicycles were intially made in very small shops. The Wright Brothers shop in Dayton comes to mind, and such small shopps dotted the country; every city or town of any size would have at least one. Even today, you can still find a few small shops that make custom bicycles. This, of course, implies that there can continue to exist other small shops that can make component parts, and beyond that manufacturers who can produce basic materials like bar and rod and tube steel, or rubber for tires and brake pads, etc. It also implies that there can still continue to exist at least some shipment of goods from one place to another. I suspect that there can be, but that there is going to have to be a considerable pruning of the top layers of Nate's pyramids. Bicycles are valuable tools, they leverage human energy with great efficiency, and they are very durable and versatile. I suspect that they are valuable enough to assure that great effort will be made to continue having them, and that this effort will extend all the backward across the supply chain to the basic raw materials required. On the other hand, the easier it is to live without something, the less likely it is to be maintained, and the more likely it will go by the wayside. Bicycles may still be available, while the lycra clothes that amateur and professional racers wear might become unavailable, because people can still get around on bicycles wearing just plain everyday clothes.

In general, I suspect that the future for most people will be a life with a lot less "stuff". People will tend to have just a few prized possessions, things they really need and want, which will all be durable and maintainable and well cared-for. There will be far less "stuff" made, and far less "stuff" available for sale in the stores, and far fewer stores in which to buy "stuff". It may be that rather than there being ten different makes of chain saw available, there might only be one; there might very well be ten or more makers of chain saws available, but each one only serves a limited radius, and there is only enough business within that radius to support one chain saw maker. Only where the radii touch or overlap do you see two different makes of a product competing against one another.

One of the things this vision of the future implies, though, is the continuation of at least some labor specialization and division. If people simply can't afford to own much "stuff", then they are going to be somewhat limited wrt the array of tools that they own as well. People may have to specialize in a particular trade or craft, and to rely upon other tradespeople or craftspersons to supply necessities that they can't produce for themselves, simply because they won't be able to have all the tools necessary to do everything for themselves.

What we are likely to see, though, are shorter and less complex supply chains. Yes, rubber will continue to be harvested from tropical plantations and shipped to temperate climes. Overall, though, there will be less movement of goods to and fro, and fewer intermediate steps in the supply chains.

I agree that an intermediate level would be for the best, but it is hard to see how to get to it.

It seems like what we had going for us years ago was a stable base to start from (crafts people who had a lot of skills, and a certain amount of imports / exports), and we gradually added to what we had.

Now we have a very complex system, and no easy way to go back to an intermediate level without a lot of planning. If we had a group of people seriously working at attaining an intermediate level (deciding exactly what the intermediate level would look like, training people to be crafts people, setting up a sustainable level of international trade that would support the intermediates level of production, and perhaps growing animals to provide part of the labor), I could envision it happening (but with fewer people than there are today).

If governments refuse to have a role in deciding what happens going forward (other than to declare that BAU should be expected), it is hard to see anything other than falling back to a very low level of specialization. It would be hard to see a group of citizens doing enough to cause this to happen, except in a very small area --perhaps one city or state, but this might imply a very low level of trade with others outside this group.

What we really need is a managed decline, and people with the foresight to see what this would need to look like, and the ability to convince others that we will need to abandon early on parts of the current system that cannot be kept up, so as to build a sustainable intermediate level.

"...deciding exactly what the intermediate level would look like, training people to be crafts people... What we really need is a managed decline..."

The trouble is, micromanagement of that sort is well-known, having traveled under names like central planning, managed care, the rule of the mentor minister, and so on, with oftentimes not-very-pretty results. The world just seems to lack suitable enlightened despots, and enlightenment tends to fade quickly anyhow since absolute power corrupts absolutely. But even in the best case, it hardly seems likely that would be enough hours in the day for an enlightened despot to make the sheer number of decisions required, much less make those decisions well.

Nor does it even seem likely that the information required to support such a top-down engineering design is really available. In a political context, that sort of thing is often begun by convening a so-called blue-ribbon panel, consisting of academics, politicians, and others habitually divorced from reality. I'd expect such a body to be off by a factor of, oh, ten, on, let's say, the number of blacksmiths that need to be trained up - and I decline even to speculate whether that would be ten times too many or too few...

I think there is truth to what you say. My guess is leaders would plan for 0 blacksmiths. Instead, they would expect we could make solar panels forever, and that people could afford to pay for them by cutting each other's hair and teaching each other how to sing.

Paul: I share your doubts about effective and appropriate direction from the top. I'm not so sure that it must be that way. It does seem that the US has a considerable leadership deficit compared to a good many of the other OECD countries. We have become a very dysfunctional nation, and a lot of the causes for that dysfunction have become systemic and embedded in our national culture. I am doubtful if anything short of a revolution, or something very close to that, can shake things up enough to really change things for the better. There is also so much conservativism and inertia built into our system that I think it very unlikely that we would see anything close to such a convulsion anytime soon - or soon enough to make much of a difference.

As I said in my response to Gail above, I've pretty much given up hope on top-down approaches, and fixed my attention and hopes on bottom-up efforts. I'm not sure that the bottom-up, grass roots approach is necessarilly better. It probably is slower and less effective in the short-run. On the other hand, I very much suspect that large-scale, centralized government is not sustainable, and in the long-run must wither away; governance, as well as economics, must eventually localize. If that is to be the case, then there is something to be said for getting ahead of the curve, and starting to rely more on local self-governance and to rely less on direction from distant national capitals.

Another part of the problem is outlined here: Might we have gotten it wrong about democracy? Put another way, as Churchill said, it's the worst form of government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time. But regardless of the form, the bigger and more intrusive government gets, the bigger and badder the mistakes it imposes on the subject population, and the more people suffer from each mistake.

If it looks better in some other parts of the OECD, that might be significant, but it might well be just random noise. For example, the EU is often vaunted - and it's certainly ever eager to preach - but is it really an enduring paradigm shift, or just one of the longer lulls in the generally awful history of Europe? There's really no way for the signal to emerge strongly from the noise within the lifetime of anyone reading this...

IMHO, we don't need a managed decline, nor anything else managed. We got the system we have because oil is so cheap. When it gets more expensive (and stays that way) the economic patterns will adjust.

Imagine how foolish it would be to make products locally, in a world of cheap 3rd world labor and cheap oil for shipping? That is the conclusion reached by nearly every fortune 500 company. When the input prices rise, that calculation will change. Products that are marginally profitable now and expensive to ship will be the first to go. Either they will be eliminated, or brought back local.

The changes must be gradual. Must be. Why? Because oil price shocks are a sure cause of cheap oil in the near future. Demand reduction, conservation and switching kick in very rapidly. Prices oscillate, but remain within reasonable boundaries. Too high and everyone cuts back. Too low and SUV sales explode.

So, nothing scary here.

mkkby:

Yes, IF (and this is a very, very big "if") the price signals change gradually enough, then people will adjust the patterns of their activities in response to the changing economics. That is Econ 101, and it holds true - IF the changes are gradual.

Of course, you know as well as I do that things don't always change gradually, especially when it comes to oil. There can be relatively sudden, wild swings, which wreak havoc on the overall economy and on a multitude of businesses and households.

This is why it is a mistake to rely solely on current price signals for long-term guidance. Most of us visiting here have now become well-enough informed to realize that the likely long-term direction is not yet being fully reflected in current market prices. At the level of individuals, households, small businesses, and even entire communities, decisions can and should be made to better position themselves in light of what can be seen to be coming down the road, even if such moves might not seem to be the most economically "optimal" choices in light of today's oil prices.

The technical term for what we are talking about here is "market failure". It is talked about very little in Econ 101 textbooks, but it does exist. Oil is such an exceptional commodity that it just doesn't fit the simplified textbook case very well at all. Even many Ph.D., and even "Nobel" prize winning, economists, apparently fail to fully grasp the exceptional complexities of this peculiar commodity. This is a good reason to therefore not place too much faith in whatever Washington and Wall Street are telling us and advising us to do, and instead to think and act independently.

I realy like the CO2 tax.

It is my dream tax. Others would pay a large portion of my tax for me.

I would suggest you consider that gradual price changes are more destructive than wild swings. Wild swings cause immediate changes in behavior. Witness the near stoppage of SUV sales when gas prices hit $4. That demand reduction has caused producers and refiners to bring production offline even today.

A gradual change lulls people to sleep. Think of the frog in the slowly heated water. People go on their merry wasteful ways until there is an even greater imbalance than before.

I say bring on peak oil, and let's celebrate it. Higher energy prices means solar and wind will finally compete head on. That means a rapid reduction in oil usage, and we'll have a cleaner world to live in.

But the oil price won't necessarily go up. If credit problems predominate, oil price will go down instead. People's salaries probably aren't going to go up, so people don't have more money to pay for gasoline, food, heating oil, etc.

Gail:

1) WRT craft skills, you need to cast your eyes a couple of hours to the north of you. Western NC is a beehive of activity when it comes to traditional hand crafts. Lots of people have set up shop here, there are very well developed marketing and promotional channels for their products, and we've got multiple schools and training opportunities, which people from all over the country come to attend and to learn. One of the reasons I'm a declinist and not a doomer is that I can see from my vantage point that we do have the base in place to build upon and expand. All that awaits is for the economics to change so that small-scale, local, and hand-made gains a competitive advantage over the large-scale, global, and automated.

2) WRT the need for managed decline, I share your earnest desire for this. However, I have largely given up hope of anything effective or appropriate being done in a top-down manner. My hopes are now completely fixed upon bottom-up initiatives. Households, neighborhoods, local communities, and bioregions to a lesser extent, are where the real action is going to be, and that is where any and all efforts to try and manage decline are likely to actually pay off. Like Marx, but for very different reasons, I expect the state (i.e., big centralized government) to eventually just wither away.

I'm sure many of us would love to get some information on what's going on in NC, if you'd care to reply with URL's.

WRT to managing the decline, I see no need for that. The economic and social/skills imbalances we see now are entirely caused by cheap oil (and cheap foreign labor). When that equation changes, production will come back local. Any attempt by "leaders" to influence that will certainly gum up the works. We all know what happens when .gov sticks their noses in things. They spend resources on nonsense because that's what the business as usual special interests cry for.

"people with foresight"---

My how I wish there could be more of these people!

Where I live now there were a few green fields left (they weren`t worth developing before, people had enough because there were bigger projects on-going (these were part of the credit boom)). But now out of desperation, of govt and banks and private developers, these few green areas, which would have fed people when the situation gets really bad, won`t be available. There are many abandoned buildings but these are too costly to remove--it`s cheaper to develop a green field.

Would it be possible to convince anyone in authority that there will be a sharp discontinuity?? I somehow doubt it. I`ve thought about this a lot. The people at the top of the pyramid won`t tolerate any disruption in the flow of their revenue (taxes, fees, etc.) They`ll sort of force the people at the bottom (laborers, etc.) to keep developing, to keep at BAU for as long as possible (using scemes like lowering interest rates, etc.). The laborers might not care if they were farming or running a bulldozer, but guess which one brings the local govt or a bank some revenue, while farming will only feed the poor guy with the plough, not the guy in the suit.

The process of wealth destruction is really quite orderly and proceeds along lines of education and social standing. No one will force it to go faster because then the "smart" people in the cities will starve first. Unacceptable!!

Agreed.

You disregard nuclear power. If we utilize the fuel (uranium or thorium) fully, such as with the LFTR, we can power the world for as long as we need to, quite effortlessly. Ships can be nuclear powered as well, of course. There has long been a transition towards electric power in developed countries and this transition will continue. If our way of life is threatened by energy scarcity, the paranoid regulations that surrounds nuclear power and make it expensive will be eased, and we'll soon see a whole host of new applications of nuclear power.

As others have pointed out, in a way: the doomsday scenarios prevalent in this forum depends on a swift and irreperable oil shock. This is probably only possible as a result of a particularly destructive WW3. In the case of ordinary depletion, we will adapt by way of market mechanisms.

I suspect that there will be some nuclear power around for a long time to come. However, it is a fact that after TMI & Chernobyl nuclear development slacked off substantially. At this point, even if we try to ramp back up it will be a struggle just to replace losses due to decommissionings. Net increases in capacity above and beyond that will be very hard to do. It must be done right, and that requires a lot of time, and a lot of resources, including skilled people in short supply, and money (also in short supply).

Nuclear presently makes up about 8% of total US energy supply. I don't see that increasing by more than a couple of percent over the next couple of decades even under the most optimistic possible scenarios. The good news is that might help to make what is coming more of a decline than a crash, but there is no way that it will be enough to sustain the economy at present levels.

Long term I still see the US (and global) economy needing to get to levels that can be sustained by renewables alone. Greer is thinking that will equate in the US to around 15% of present per capita GDP; I'm a little more optimistic in thinking that 25% is not yet out of the question. I don't see a US economy operating at those levels as being capable of sustaining nuclear power at any level for very long. At best, we can let it unwind and slowly decomission plants in a responsible and orderly manner. That's about the best I think we can hope for.

No, if you try to ramp, it will be easy to do net increases. You kept a nice pace in the 60-ies and 70-ies, and you have far more resources now and nuclear designs are simpler and more standardized. If you do some extra LFTR research beforehand, you may find yourselves having even simpler designs which utilize fuel much better.

That's b/c you are bathing in coal and natural gas. Otherwise, you'd already have a nuclear economy.

What are you talking about? As I said, you are awash in coal and ng. You have no real problem.

Repetition don't produce truth. Why do we need to get to renewable energy levels when there is abundant nuclear fuel? As I said, nuclear can power the world economy forever. (Not literally forever, but almost.)

Why not? India is building at 2% of US nominal GDP per capita. (6% in purchasing power parity.) China too is far below 25%. Actually, the US, when rapid buildout commenced in the 60-ies, was at 25% of today's GDP level.

jeppen:

Oh, my goodness! A real, live, actual technocopian! I thought your breed were just about extinct!!

You are obviously far, far more optimistic about things than I am. Not wishing to get into a big argument, (I'll leave that to the real, live actual doomers, of which there are many here and who LOVE to do that!) I'll just mention a couple of points:

1) Construction of new nuclear plants in the US has not yet even begun to ramp up. At best, there are a few tentative plans and initial filings with the NRC to begin the permitting, and just about all of these few are intended to go on the same site as existing plants to replace units that are going to be decommissioned. It is by no means certain as to which - if any - of these are actually going to be built. It is not certain which will be approved, and it is not certain which will get the funding from their utilities to actually go forward. If we are going to have the type of ramp-up that you envision, we have left it very late, and we are seeing no signs yet of anything really happening along those lines.

2) It is true that as all FFs start to deplete, then if the total energy "pie" shrinks then the nuclear slice of that pie accounts for a larger percentage of the total. That is not the same as actual growth in the total amount of actual energy supplied. Perhaps I should have spoken in terms of quads. Presently, nuclear supplies a little under 9 quads of our total energy supply of nearly 100 quads. I would be surprised to see us being able to increase that to much more than 10-11 quads over the next two decades or so. To be able to do so, we should already be underway on actual construction of several units, and have many more farther down the planning pipeline than they are so far.

3) Even if PO becomes immediately obvious, and a strong national consensus emerges around building out alternative, non-carbon energy sources (both to replace oil and to combat GCC), that does not mean that you are also immediately going to get a consensus in favor of the type of massive ramp-up of nuclear capacity that you envision - or indeed, that you are going to get a consensus in favor of even building replacements for decommissioned reactors. It was not money or technology or manpower that brought nuclear construction to a halt, it was the NIMBYS and BANANAS, and they haven't gone away.

4) The US political system is obviously dysfunctional. We were unable to reach a consensus that would bring the US health care system up to anything close to OECD standards; we have been so far unable to reimpose even the most rudimentary regulatory regime on a wildly out-of-control and hugely destructive financial industry; and there are a great many other huge national problems that are simply being ignored or papered over, while the politicians continue to kick the can down the road and past the next election. What makes you think that we would be able to reach a consensus on energy, especially something as controversial as nuclear power? Pointing to what is possible and has been done in other countries ignores the reality that the US isn't other countries, we have some unique, deeply embedded and systemic dysfunctions in our political system, and that prevents replicating here the successful experience of other countries. If you think that your vision is possible, you must first map out exactly how the entire US political system and culture is going to be transformed into something that can actually act in the decisive and effective manner that you presuppose.

5) Finally, what might be the biggest issue of all: money. Nuclear power plants are expensive. As you've probably noticed, the US economy isn't doing very well right now. Given the massive unemployment and massive amounts of debt built up, the platform just doesn't seem to be there to support renewed boom times anytime soon. Meanwhile, it is not just nuclear that would need massive capital investment; oil and gas exploration and development also need to be ramped up, and renewables, and energy efficiency initiatives like passenger rail, and our crumbling infrastructure needs repairing. There is going to be a huge capital crunch this next decade, the US economy is simply not going to be able to generate the funds needed to do all of this; we can't take it for granted that other nations are going to continue to lend us their money, either - they'll have their own capital investment needs. It is by no means clear to me, or undoubtedly to many other people, that nuclear deserves top place on the priority list.

First, I consider myself quite mainstream, at least when it comes to enlightened economic thinking and our future. While you guys tend to lean towards doomerism and leftist economic misunderstandings and mythology.

1. Quite - the US are at best in the very initial phase of a nuclear ramp-up. But again, you don't need to ramp - you are awash in coal and ng.

2. As I said, you can increase nuclear many-fold, if you wish to do so.

3. The US seems to become quite powerful in the event of crises. As I said, if your way of life is threatened, you'll do what's necessary. But the most likely scenario is that Asia will go first, and that the US will simply follow once the Asian R&D and deployment have proven nuclear's superiority.

4. You exaggerate the problems of the US political system. Btw, you have a health care system that in most ways are superior to OECD standards, but you are about to destroy this with socialism instead of deregulating and continue to lead the way. Also, you don't really need to regulate the financial industry more than you did in 2007. On the contrary, it would be better off with less political involvement.

5. Nuclear isn't expensive - the costs are just very up-front (but wind is even more so). Nuclear is cheap, but is made moderately costly by politicians' red tape and excessive safety demands. The US have an enormous manufacturing capacity and you could ramp easily. Debt and unemployment are no obstacles here, neither is cost. But you are right it might not be top priority, as you have all that coal and ng.

I'm not sure what the fascination with rail is all about. It makes sense for long haul freight, but not people or replacing trucks for short haul. Alan Drake's "Light rail facts" are clearly misleading. He claims LRT is cheaper than buses but fails to consider the capital cost. Take San Jose (where I live for example). When you add the capital cost over 30 years, it increases from $0.86 to $5.00 per pax mile [$4.2B/33m pax-mile annually/30 years]. Taxi's are competitive with that cost!

High speed rail is great for replacing planes but does not get kids to school, daily shopping or help with most commutes.

Realist isn't much of a realist. Rail seems to have worked for much of the world for over 150 years. I doesn't work in the U.S. because we didn't make it work. That'll change.

Agreed.When the choice is to grade a track bed and put down light rail versus grading a road and paving it well enough to withstand heavy trucks is the choice, and maintaining the pavement over the years versus maintaining the tracks, rail is a big winner even before taking fuel efficiency into account.

Paving is a very expensive labor, energy, and materials intensive undertaking.Pavement seldom lasts more than ten years without annual minor repairs and repaving on routes heavily used by trucks.Truck tires cost hundreds of dollars each and last only a couple of years if used constantly.Steel wheels on running on steel track can last for generations.

I strongly suspect that given the possibilities for easy electrification we will see many streets converted to light rail someday in industrial areas-and a lane of multilane intercity highways might be sacrificed the same way to expand the rail system as the availability of motor fuel declines.

Such tracks might also be suitable for dual use as street car tracks.

I see as you do mac. For years I've been watching them rebuild Interstate 10 thru Houston. Amazing concrete road beds at least 2' thich with massive amounts of large guage rebar. I don't have a cost number but I've also been watching them relay a railline from Houston back down towards the Mexican border. I drive along it every couple of weeks. They spared no expense: new concrete/steel tressels, concrete ties, big sidings. Just a guess but I say the heavy duty road beds have to run several time as much as the new track. Even outside the city I-10 has been upgraded with major new bridges, over passes and road beds. Even our heavy p/u's don't require such heavy designs.

Steam lift, solar powered airships, anyone?

I expect asphalt to be replaced by concrete because asphalt costs will go up faster than concrete costs. Since concrete lasts much longer that seems like a workable solution.

Does someone see a reason why concrete will become too expensive too?

Not sure what you mean. How are we going to afford light rail.Even Portland's "success" has not offset most of the cars on the road. At $2 (portland)-$6 (san jose) /pax mile, it is 4x more expensive than driving. The only reason light rail works is that the US taxpayer is covering the capital cost in the "chosen" areas. It can't scale nationwide.

You aren't including the costs of owning the automobile , only the marginal costs per mile.

And the costs of public transit will come down a lot once some of the sunk costs are recovered and as ridership goes up.

I parked a car and a truck this year because as the amount of use went down , the per mile cost went up.Toward the end of the time I kept the extra truck on the road, sometimes it cost ten dollars a mile to drive it if it was used for only one short trip in a month.

It costs a hundred thousand dollars a mile to repave a country road.How do you propose we pay for that later on when the price of asphalt and diesel are much higher?

But I do agree with those who see a return or switch to rail as being slow and painful;and the folks who are not near the tracks will fight tooth and nail to save thier paved roads of course.

Being located way out in the boonies I don't personally look forward to the local roads being poorly maintained so those who live in or near the cities can enjoy public transit but in the long run I'm on the losing side.

But with fuel taxes being diverted to other uses and people driving less in more economical cars I can't see the current primary highway network being any more than adequately maintained very far into the future, and the secondary roads will probably get rough enough we would finally have a use for all those suv's if we could afford a tank of gas.

Actually 50 cents per mile includes the cost of owning the car, insurance, tires, O&M, federal highway tax. But not county taxes or parking, tickets. Perhaps 75 - 90 cents is a better number.

That means the average US driver spends 12000 x 0.90 = $10,800 per year on driving. If you ask them to send $20,000 - $40,000 for light rail. Would they do it?

Gas is only $0.12 per mile so even tripling the price of gas will not change the picture.

I agree that we need to get away from the highway system. But we need something new not light rail.

I would just call this system ultra-light rail reconfigured. From an engineer's point of view we're talking about an automated people mover:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/People_mover

and a pretty cool one. I'm not set on trains, just much more efficient ways to move people than we have now.

yes, given the high cost of labor, automation is a reasonable way forward. I think the race will be between automated cars and automated people movers. Given the challenge of batteries and complexities of automated vehicles, I'm putting my money on micro people movers, ultra light rail. Whatever you would like to call it.

I'm always interested in "NEW" that actually might work for a large percentage of the world's population. I also love Scifi... "Beam me up Scotty!"

Realist,

Your figures are good for people who are average drivers. My mistake earlier was failing to point out that people who can and actually do use light rail or subways or street cars or buses regularly are likely to put relatively few miles on thier cars, driving up thier per mile costs substantially.

And for those who can both avoid car ownership and only pay for a ride occasionally thier savings are enough to accumulate quite a substantial personal portfolio over a decade or two if they don't spend the savings.

I can't envision anything that would work a lot better than current public transportation technology if it is implemented properly with continious marginal improvements.

Maybe one day we can have automated single passenger street cars that can be summonsed like a taxi .You would simply swipe a card or drop in some coins , punch in the address, and sit back with your paper until the chime notifies you of your destination.Such cars would rum mostly during off hours as I see it.I think light rail could evolve into something along these lines eventually.

Embedding markers easily detected in the rail or rail bed every few feet would enable the cars to navigate faultlessly, and (reasonably failsafe) programming should virtually wipe out collisions with other cars .We already have seeing eye tech adequate for such a system.

You could drink as much as you like and still get home safely .;)

If they can't afford to maintain ordinary two-lane roads, I don't know that they're going to be able to keep very many tracks up to the persnickety FRA standards required to run even a freight train at even 30mph. In the area where I live, there are a fair number of tracks, and nothing ever moves faster than about 15mph. The problem with that is that the number of freight cars tied up moving stuff is directly inversely proportional to the speed. At some point you have so much money tied up in dysfunctional infrastructure that it's not worth it, which is partly why many of the tracks have been torn up. So if it goes downhill as far as is being discussed here, it'll be more like very poor countries now - beat-up vehicles or carts swaying over potholed mud roads, with fancy expensive rail reserved (if at all) for the favored and (relatively) rich districts where government employees and politicians congregate.

Where? Copenhagen? I was just there. They are spending $$$ per mile to dig tunnels to expand their subway system. They cannot pack in more trains on the surface without banning the car. Many seem to be hoping for a total collapse so the trains can get built. Not very proactive.

Cars are not he answer either, but I think we need to be more creative in our transportation solution than 150 year old technology that has huge barriers to implementation.

I agree that rail isn't a pancea but we surely need better rail in the U.S. as part of the mix. We've gotten ourselves into a tight spot, transportation-wise and, like energy, we're going to need multiple solutions. NG buses, electric rail and trolleys can all play a part. I've traveled a lot of the world on trains. One place rail doesn't seem to work is here in the U.S. Why is that? It did once. It's OK to give GM billions of $s, but Amtrak gets treated like a poor redheaded stepchild, all while China launched the world's fastest train.

Show me a 1st world country where trains account for even 20% of total passenger miles traveled.

In China, what's growing faster? Car usage or train usage?

Rail works well for the US for freight. In fact, freight rail works better in the US than in Europe.

Europe's success with passenger rail is smaller than America's success with freight rail. Europe's success with public transportation is much exaggerated. A UK government report on transportation contains a chart in chapter 2, "Figure 3: Overall mode share of distance travelled (%) in 2003", that speaks volumes about mass transit in Europe:

All forms of public transportation account for a small percentage of passenger miles in Europe. This does not bode well for public transportation in the US post-Peak Oil.

Hey!!

What happened to every country south of the equator?

Its worse then that, rail is realy good when you have or build dense neighbourhoods around the trainstations, subway stations and so on and need higher capacity then busses, faster speeds then busses to make longer commutes practical or higher quality service then busses to attract a significant number of car commuters.

Rail infrastructure is not especially usefull for suburban living, it needs real towns and cities.

Nobody in Sweden is planning passanger rail in areas with low density with one exeption and that is additional passanger traffic on old railway lines to more or les try to save the life and sunk cost of shrinking small towns. The investments in passanger rail are essentially a part of the urbanisation trend where the best towns grow even more and rail makes those towns even more attractive and extends the growth centers over a larger geographical area.

Rail is of limited use if you are too poor to rebuild towns and cities and make them denser. Busses and trolley busses makes more sence if you cant invest a lot and in realy poor countries are overloaded mini busses a solution.

I suspect that ten or fifteen years from now, most people now commuting by car are going to be commuting by bus. The simple fact is that buses can be deployed with far less up-front planning and investment than is the case with any form of rail. That type of planning and investment is not underway now, and there is no prospect in sight of it beginning in earnest any time soon. Ergo, people will be riding buses, because there will be NO other alternative. Buses are the only things that can be built and bought and placed into service quickly enough.

Jam-packed full, the energy economics look fairly good for them, too.

People are going to hate it, but except for those few that are able to locate their housing close enough to their workplace so they can walk or bike, they will have no alternative. I think it is a pretty safe assumption that when people have no alternatives, they will do the one option open to them that they can do.

Maybe we'll get around to building out a lot, or at least some, of those urban rail systems eventually. Even under the best case scenario, however, at this point we've left it so late that a lot of people are going to have no choice but to take the bus at least for a long transitional period while the rail systems are being built. It is also quite possible that the US economy will decline so quickly that we'll never be able to come up with the capital to build many of those rail lines.

Why do you think that People are going to hate it? Maybe we can learn from experiments like this. I've seen something similar in other parts of South America.

Streetfilms-BRT Transmilenio (Bogotá, Colombia)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SRGoketbIZE

I commuted by bus for years and didn't hate it. Then again, I'm not most people.

People have other choices:

- Scooters.

- Motorcycles.

- Bicycles.

- Pluggable hybrids.

- Pure electric cars.

Most who can afford a PHEV or pure EV will drive one. Most people will continue to avoid public transportation - including most of the people who praise public transportation at this web site.

The biggest comparative advantage is wage differential. Workers in many developing countries make less in a day than the fringe benefits of one hour’s work of a USA auto worker.

International shipping trade existed long before efficient engines. The first steamships had efficiencies below 10%. Two stroke diesel engines in modern ships are 50% efficient. As long as it is affordable to ship grains and other foods, there will be no problem shipping higher valued manufactured goods.

It was cheaper for a sailing ship to bring cargo across the Atlantic to the USA in 1800 than to transport goods 32 miles over land in the US. (The Rise and Fall of Infrastructures, Grubler). Before roads, locomotives could transport goods across the USA cheaper than they could be carried 16 miles by wagon.

If trans-ocean trade is diminished is will be because of economic depression brought on by loss of manufacturing jobs in developed countries rather than high oil prices, although collapsing western currencies will cause the price of oil to soar.

Electric street railways are the most practical alternative transportation. We could build out a streetcar system faster than we could turn over the auto fleet, especially since there is no affordable electric car and hybrids have too slow a penetration to make a difference in the remaining time of affordable gasoline.

I agree - but am of opinion that it won't just be one (or several) currencies that collapse but probably all, over time. So the above import substitution ideas, taken with a probabilistic world view, make absolute sense, not only for US but for other countries. Trade is important, but past a certain limit (which we are well passed), it becomes a liability due to potential for disruption. If we can't buy a Lamborgini it's not a big deal - spark plugs, oil, and wind components are another story entirely...

Isn't the big issue whether the decline in trade is very orderly, such as might happen if the only issue is higher prices, versus a disorderly unwind, such as might happen if countries stop trusting each other, if credit is the major issue?

I know a lot of early thinking on localization (and a lot of other things) was dominated by the "high price" view of the future. But if the real issue is "credit collapse - currency problems", the decline may be very different. We may simply be unable to get some products (or in adequate quantity). Liebig's Law of the Minimum may become more important. If a product is 99% local, but the remaining 1% cannot be obtained locally and there is no substitute, it may be just as unavailable as one that is only 1% local.

The biggest problem I have now is that parts are discontinued and products become obsloete so quickly.

Paul: I think that people are going to start looking for well-built, durable goods that are easy - or at least possible - to maintain. The throw-away society is just about over, because people are not going to be able to throw away and replace stuff much longer.

This in turn I believe is going to lead to a shift in preference to simple, single-function products and away from complex, multi-function products. I am already operating this way. For example, I finally had to replace our gas range this year. I intentionally avoided the more complex products with all the bells and whistles, and settled on a very simple, no-frills model. I have every confidence that I can keep this one running for the rest of my life, and certainly for many years longer than I could the more feature-laden models.

Once things move in this direction, we are likely to start seeing more people getting into repair businesses, and larger inventories of repair parts being maintained. I also suspect to start seeing operations that custom-fabricate repair parts where OEM parts are no longer available. Right now, it doesn't make economic sense to have any of this, because brand new replacements are so cheap. The economy is going to have to decline to the point where few people can afford to buy anything brand new before we start to see these types of transformations - but it will happen.

WNC - Nice transitional picture you paint there but I have to disagree a bit.

What I am seeing is more and more people purchasing the least expensive (talking up front cost only obviously but that is all 99% of population care about) and anyone attempting to produce and/or sell quality, and therefore expensive, goods are going out of business left and right.

The economics are just so terribly skewed against the transition that we all hope for and write about that I just don't see how it can happen.

I have not seen anyone lay out a method that I can buy into that isn't mostly wishful thinking. I am seeing so many good people and business loosing everything that I want to cry.

eeyore:

If you just look at what is happening in the big chain stores, you are absolutely correct. However, there are things happening which are flying under the radar and thus are so far out of sight.

For example, check out ebay. There is a booming business being done in the resale and purchase of used stuff. This is stuff that people are buying INSTEAD of going to the store and buying something new.

For another example, check out online sales on the Internet. They are growing very rapidly relative to what is happening in the bricks-and-mortar traditional retailers. It is not necessarilly the same stuff that is on offer in the stores that people are buying, either. There is very much of a "long tail" effect here. The stores just offer a very limited selection of merchandise. My experience has increasingly been than I simply can't find what I am looking for, even in the largest stores, so except for routine stuff like groceries I have pretty much given up on stores. I find it far easier and quicker to get what I need off of the Internet. I suspect that increasing numbers of other people do also.

A personal example: I mentioned the new gas stove I bought. It is a Peerless Premier, built in the USA. I bought it from Lowes, but online. They don't have a display model in their store, so I wouldn't have been able to get it there; I HAD to find it online. It also happened to be one of the cheaper models (probably why they are not making it easier to buy). As I said in my post above, it is a very simple, durable appliance without all the bells and whistles. (Interestingly though, it not only has electric ignition but also the capability of lighting not just the top burners but also the oven burner by match during a power outage - the only make available with this very desirable feature, which was the main selling point for me.) Yes, a lot of people are not buying something sensible like this, but are forking out hundreds of dollars more on digital crap that will stop working in no time. Nevertheless, the type of product that I bought IS still available - if you look for it.

It is true, though, that a lot of good guys have been forced out of business by the juggernaut of big global corporate manufacturing and retailing, pusing cheap junk down the throats of all-too-willing consumers. This will continue for a while, unfortunately. All the more reason to go against the flow and vote with our precious few dollars for those precious few producers and retail channels that are also going against the flow.

The finger trap has tied all the currencies together making it much more likely that all will collapse imo.

And of course as we trade the higher costs of local production for the lower costs of widespread trade part of the price is a growing loss of security.

The "locking in" effect can and does run a lot deeper than just the loss of the first level of independence-losing the furniture industry for instance-all the necessary "industrial culture" associated with furniture can also be lost if the "minimum operating level" or volume of business ceases to exist.

Lots of small electric motor repair shops (which quickly and economically repair BIG EXPENSIVE motors) have closed in the southeast because as the furniture mills close there is no longer enough business to support them-meaning that a local manufacturer of some other product loses a key supporting small scale industry.

This phenonenom also seems to carry over into politics too-we put in regulations and codes that protect a consumer of lettuce in New York from bacterial pollution resulting from using manure in Florida fields-but at what ultimate cost? The loss of the farm culture, the purchase of the fertilizer, the additional expense of disposing of the manure in other ways......

As someone said , when you pull on one string in the natural world you find that it is tied to all the other strings.The more far reaching strings we create, the more likely one of them eventually loose a disaster upon our heads someday.

The graph that Nate put up on energy cost v. speed illustrates that freight transport in general is more energy efficient than is passenger transport. What this suggests to me is that as energy supplies for transport become more scarce and expensive, it is passenger transport rather than freight transport that should feel the effects first.

I suspect that goods will continue moving across the oceans by ship long after inter-continental travel is something that only diplomats and a handful of other VIPS do, and even that only on a very infrequent basis.

You are half right. Rail is better than rood, but personal vehicles are better than 10 ton rail cars. We need personal rail. Put on your thinking caps.

I do a lot of shopping at a Fleet Farm which happens to be located near a Walmart. They compete on gas prices. While Walmart offers 3 cents off the posted gas price with a Walmart Card Purchase, Fleet Farm gives a 4 cent off gas coupon with any other purchase.