Oil Production is Reaching its Limit: The Basics of What This Means

Posted by Gail the Actuary on November 16, 2009 - 5:35pm

I decided to write another rather basic level article because there are so many people I meet who have heard a bit about the oil situation, and it is hard to point to one single article to give an overview of some of the current issues. Regular readers will find many repeats of graphs. There are some new ones, as well, from the Denver ASPO-USA conference. Because there is so much to tell, the story gets a little long.

We live in a finite world. It is clear that at some point, we will eventually start hitting limits—we won’t be able to extract as much oil, or we won’t be able to mine as much silver or platinum, or fresh-water aquifers that have built up over millions of years will run dry.

We are reaching limits in several areas, but the one I would like to talk about here is oil production. Oil is essential, because nearly all transportation depends on oil, and because a huge number of goods use oil in their manufacture (including textiles, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, asphalt, plastics, lubricating oils, and computers). Oil is also essential for our current agricultural system--growing food and transporting it to market.

Why people are concerned about a decline in oil production

Quite a few people are familiar with the peak oil story. If you haven’t heard it, here it is in a few graphs.

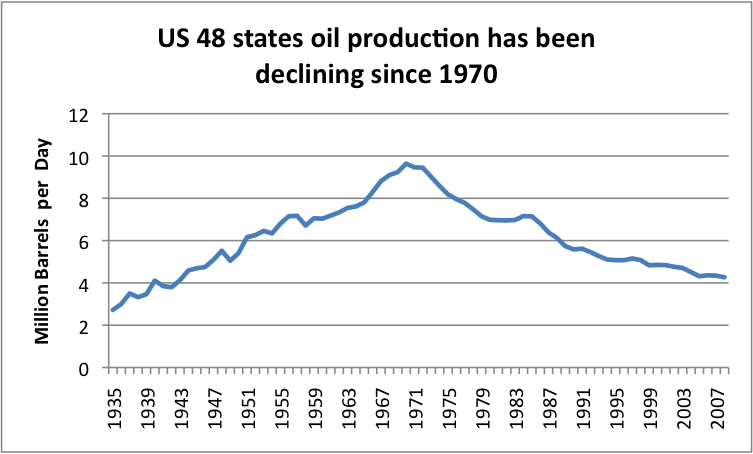

Once upon a time, the US was the biggest producer of oil in the world. Our production was growing rapidly—until suddenly, oil production began to decline:

Oil companies had generally not realized that anything was amiss prior to the decline, and in fact, were forecasting continued growth for many years. This decline in production for the US had been predicted by M. King Hubbert in 1956, but few believed him. He also made predictions that world oil production would begin to decline around 2000. His prediction was based on the fact that it was a finite resource, and it would become more difficult to extract over time.

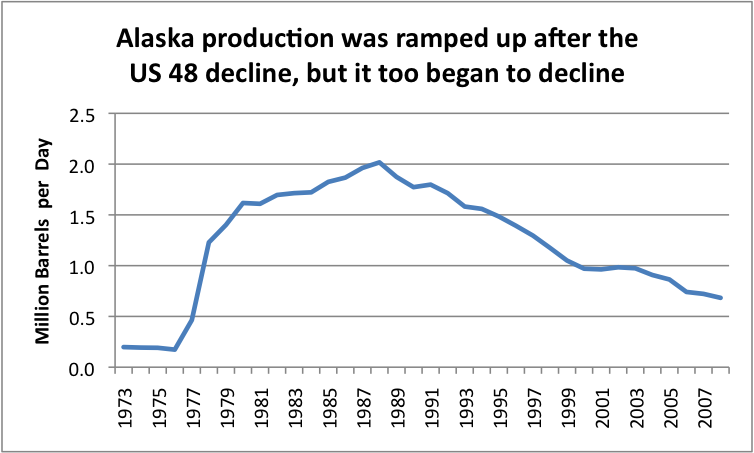

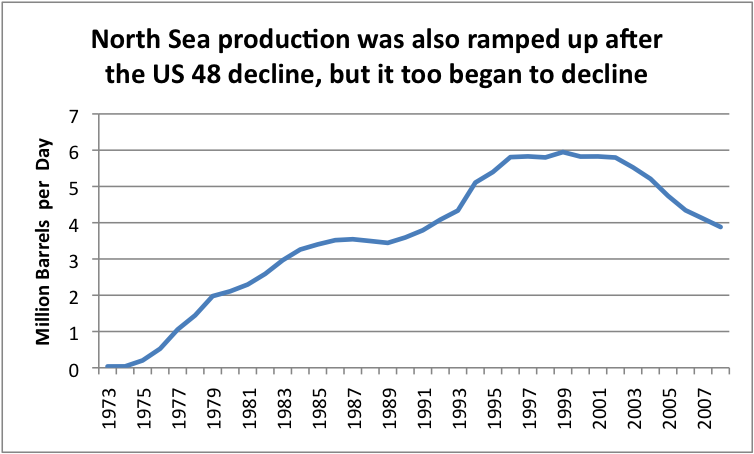

After the decline in oil production in the US 48 states took place, production was expanded elsewhere, but after not too long, these too, began to decline:

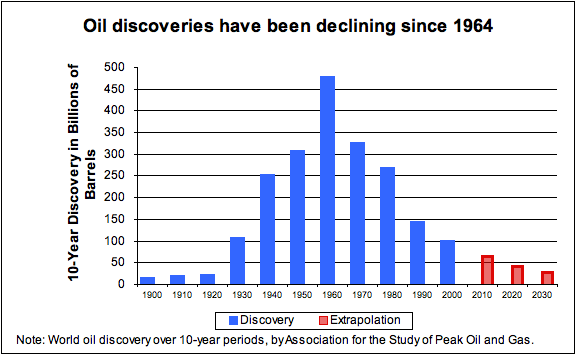

Finding new inexpensive places to drill became more and more difficult, as the world got better explored, and the easy-to-exploit areas were tapped first. One problem was that new discoveries of oil in liquid form kept getting smaller and smaller:

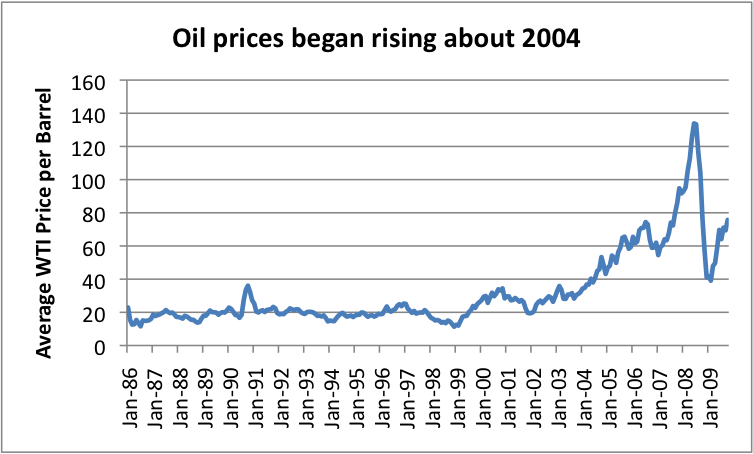

One might think that at some point, world oil production would start running into difficulties. Not too surprisingly, between 2004 and 2008, we experienced a long-term rise in oil prices.

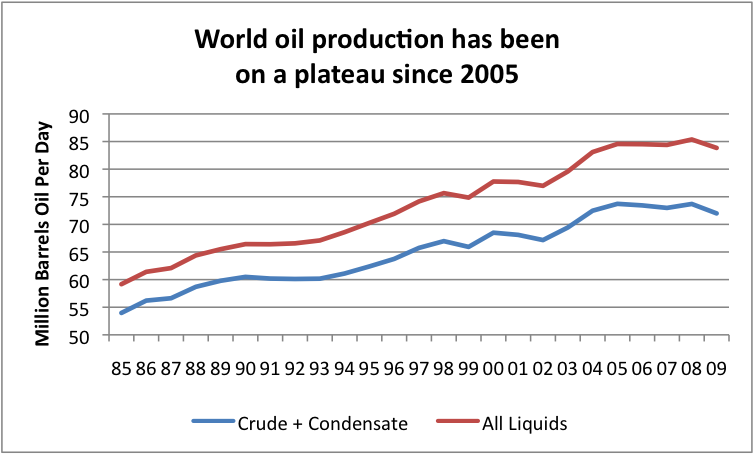

During the period when the price for oil was rapidly rising, one might think that oil production would be rapidly ramping up to meet demand, but this was not in fact the case.

Oil production was in fact quite level during this time period, with only a slight uptick in production in 2008, about the time prices hit their highest point.

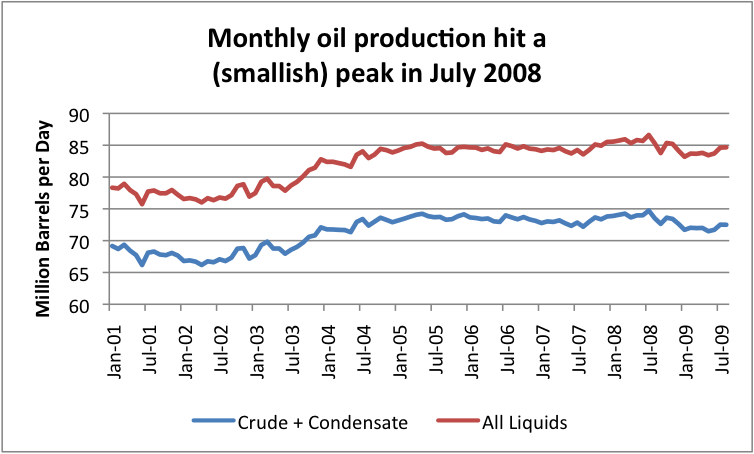

Oil production hit its highest point ever in July 2008, the same month that oil prices peaked.

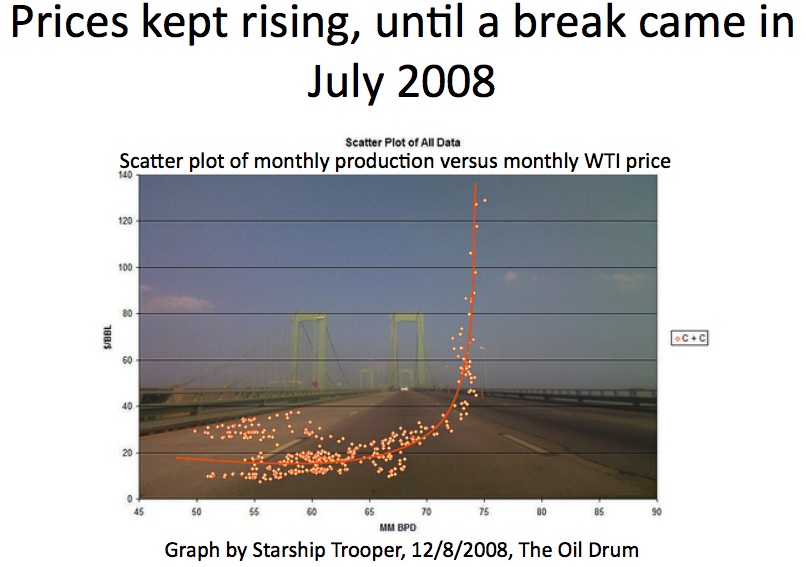

Figure 8 compares something that most of us wouldn’t think of plotting together—monthly oil production (crude and condensate in million barrels per day) versus oil price. What one can see from the graph is that oil production just barely increased, even as prices rose rapidly. One gets the impression that oil supply is extremely inelastic—no matter how much price rises, supply doesn’t increase by much. This is what one might expect if oil production is reaching its limit.

All of these graphs seem to point in the direction of world oil production approaching its limit. There are a lot of suspicious signs—particularly the virtually flat volume, with rising prices.

I’ll continue with what happened recently, but let’s stop first and look at the connection between oil and the economy.

Oil and the Economy

If oil is essential to the economy, because it is used for food and transportation and many other things, one might think that lack of oil might have an adverse impact on the economy. There are many ways of seeing this is in fact the case.

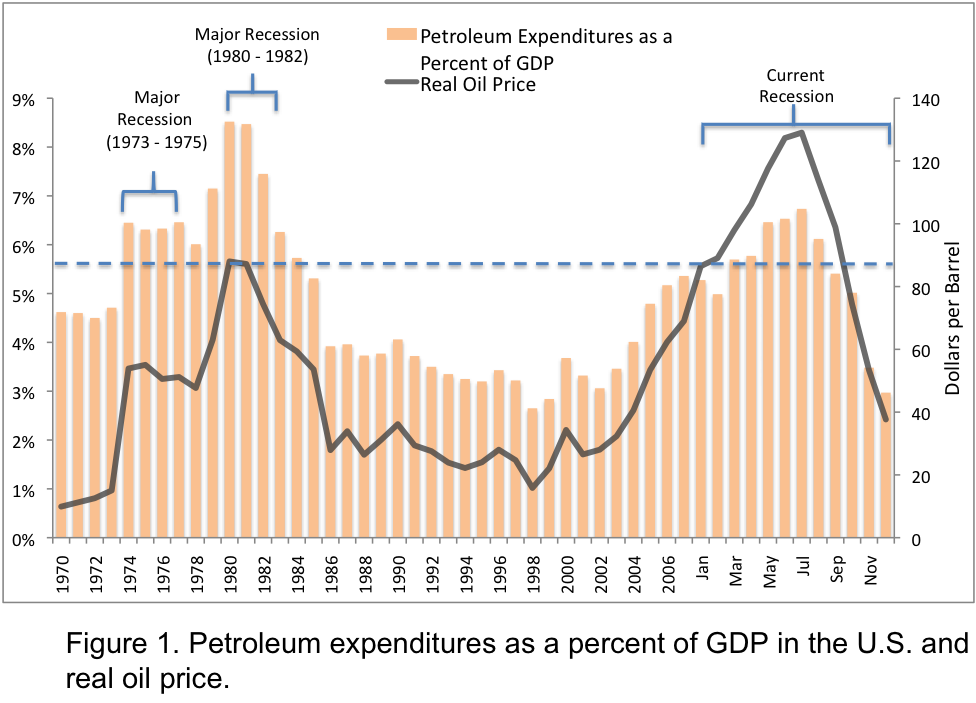

Dave Murphy of The Oil Drum has shown that if the oil price goes much above $80 or $85 in inflation adjusted terms, the economy tends to go into recession.

The problem with $80 or $85 barrel oil sending the economy into recession is the fact that much of the oil that remains is “difficult oil”, that is expensive to extract. If producing oil at this price is an issue, then much of the remaining oil may throw the world further into recession—because when people spend so much money for oil, (and indirectly for food, and for all things that have a transportation cost component), they don’t have enough left over for everything else. People cut back on non-essentials, and soon the economy goes into recession.

from ASPO-USA Presentation.

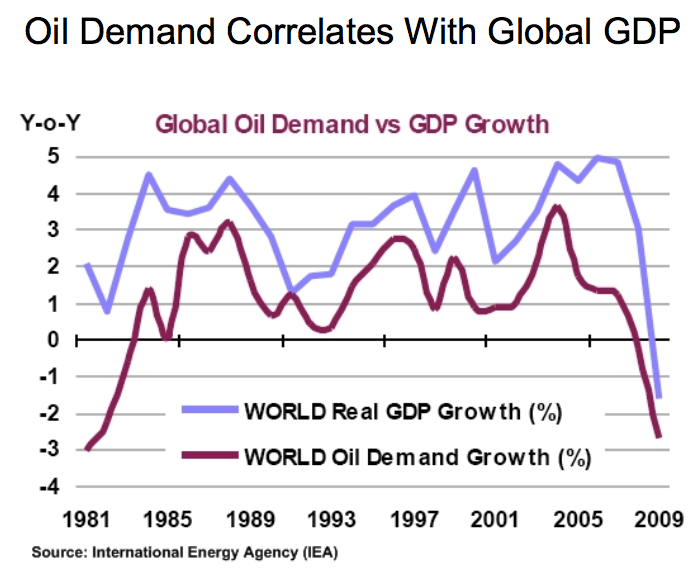

Dave Cohen of ASPO-USA shows in Figure 10 that growth in global GDP seems to be highly correlated with growth in global oil consumption. This would tend to mean that if oil production actually starts declining, the world economy is likely to begin declining as well.

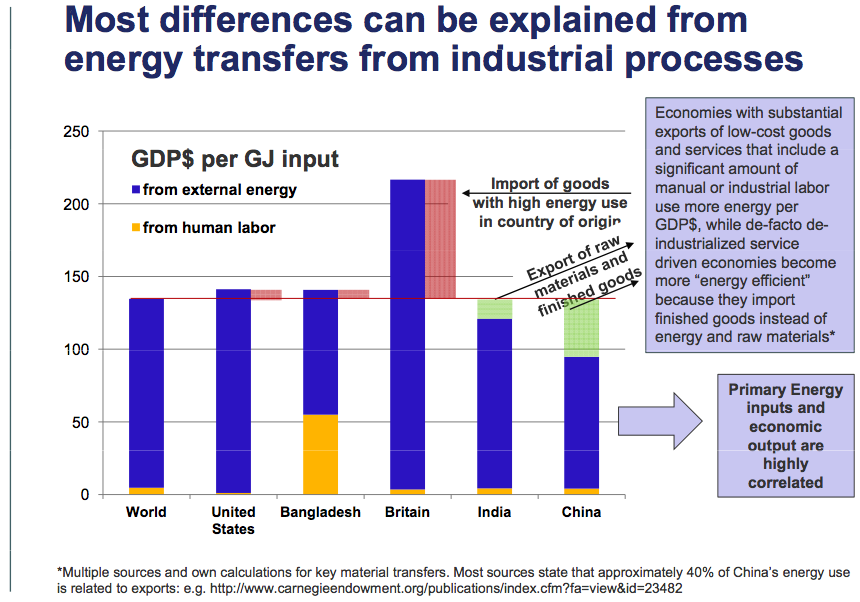

There has been much talk recently about the US economy becoming less tied to oil. A recent presentation by Hannes Kunz shows that much of what appears to be an improvement is related to “offshoring” of the more energy-intensive industries (Figure 11.) This further emphasizes the need for energy, if we are to have true economic growth.

We saw in Figure 5 that the price of oil went up in the 2004 to 2008 period. Sam Faucher has shown that a shortage of oil supply (relative to what one would expect the economy to use based on trend) can be shown to underlie this increase in price. A 1 million barrel a day shortfall in oil supply for OECD seems to correspond to a $20 barrel increase in oil price.

Growth and Credit

It is bad enough that a decline in oil production (or an increase in price above $80 to $85 barrel) tends to send the economy in recession. We will see in this section that the credit situation has the potential to make the situation very much worse.

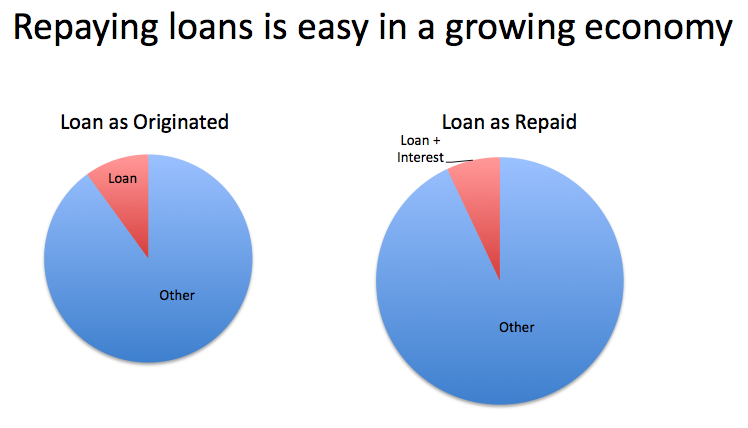

Buying goods on credit works much better in a growing economy than in a shrinking economy.

If a person (or business or government) takes out a loan in a growing economy, there is a good chance that the economy will be better when the loan is to be paid back with interest. The growing economy means that even when interest is repaid on the loan, there will still be enough for everything else.

In a shrinking economy, the reverse happens. Instead of being better of financially when it comes time to pay back the loan, one is likely to be less well off (for example, an individual would be more likely to have lost his job, or a government would be more likely to be collecting less revenue). Paying back the loan would be much more difficult, and would leave less for other needs.

As we have seen, there appears to be a very good chance oil supply will decline in the future. If oil supply declines, we are likely to have economic decline, and with economic decline, loans will be more difficult to repay.

The problem is that our whole economy is built on credit. Our monetary system is a credit-based system, in which money is loaned into existence. Our international trade system is based on credit. The US has been buying far more oil than it could pay for based on the value of the goods it exports—the difference is made up with more and more promises to pay in the future.

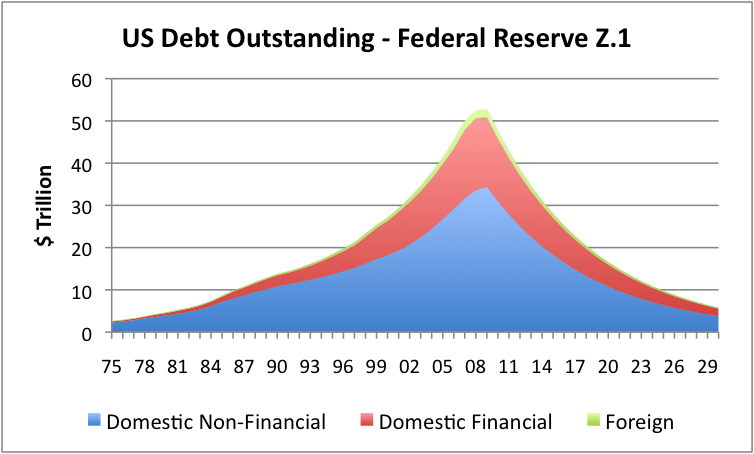

The amount of debt outstanding in the United States (and many other countries) has grown greatly in recent years. This growth in debt has had a beneficial impact on reported GDP, since GDP calculations reflect expenditures without subtracting out debt related to those expenditures. In fact, the loosening of housing credit in recent years may have been an attempt to cover up the lack of “real growth” after the growth in oil production started slowing about 2004 -2005. An increase in debt would give the illusion of growth, and have some of the same benefits—higher reported GDP, rising home prices, rising stock market prices, and increased ability of homeowners to draw down the rising equity or their homes, to use for yet more purchases.

The problem if debt availability starts decreasing is that we start getting to all kinds of unpleasant results. People are less able to buy houses and cars. Housing values drop and defaults rise. The value of commodities, including oil, drop, because they are less needed for producing houses and cars.

Investment for many kinds of things—not just oil--becomes more difficult, because debt financing is not available. Also, cash flow that might be used for investment is down, because of the price of commodities, and because of the inability of consumers to spend. If oil production and credit both decline, real GDP will tend to drop even more than it would have based on the relationship shown in Figure 10, because an increase in debt helps GDP; a decrease hurts it.

What happened to oil after July 2008?

We saw in Figure 5 that oil prices reached their peak value in July 2008. But why?

It seems to me that a major part of the reason must have been a change in the credit markets. Credit markets started unwinding about then, and this brought the support for the price of oil down. Without credit, consumers could not buy all the consumer goods that use oil, and businesses, even intermediaries in the oil business, couldn’t necessarily buy the goods they want.

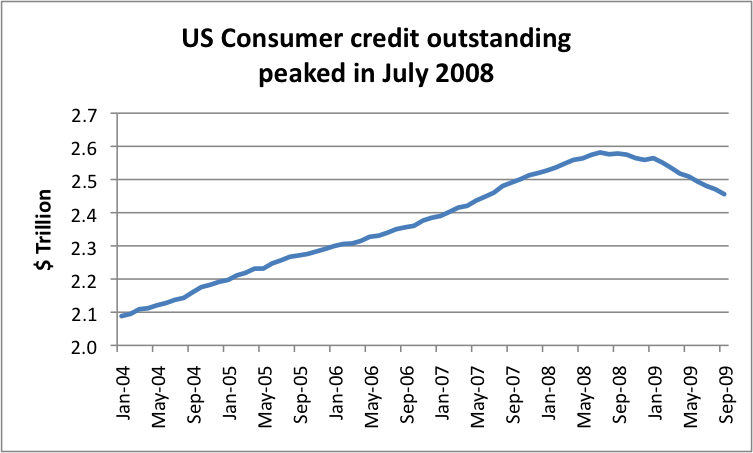

Figure 15 shows that US consumer credit peaked at the same time as oil prices. The amount of mortgage debt also began falling about the same time. Lending in generally became tight, especially later in 2008.

Even now, we read in Platt’s report Hedging in the Oil Markets –Challenges in 2009 and Beyond:

Unsurprisingly it is credit and counterparty risk that tops the list of concerns amongst energy professionals when talking about managing cost. Almost without exception it is these two themes that are at the forefront of everyone’s mind. Market risk is still prevalent, but it has taken a backseat to credit as the major influence on decision making.

“Counterparty risk and credit risk are still the big areas to look at. Banks cannot necessarily sustain all of their back to back hedges. Who can you go to?” a market analyst said. “With counterparty risk – who will be there in a few months time? People are trying to aggregate credit risk rather than market risk now.”

The unwinding of credit and the associated drop in demand would explain the sharp drop in price in July 2008 (Figure 5). Even now credit has not fully recovered. Given the problems one would expect with credit when oil is declining in availability and exerting a downward impact on economic growth, it is not at all surprising that credit is still a problem.

Prices have not risen to their previous level, because of credit issues holding demand down. Funds available for investment have dropped because (1) less credit is available for financing, (2) the lower commodity prices leave less for cash flow, and (3) at the lower prices, more expensive types of investments no longer look profitable.

Looking Ahead

I don’t think anyone doubts that there are huge resources theoretically available to the oil and gas industry, including oil sands, shale oil, polar oil, and very deepwater oil.

The problem is that most of the oil available, especially to the Independent Oil Companies, is either has a very slow flow rate, or is quite expensive to extract, or both. The flow rate of any oil that has to be melted (such as oil sands or very heavy oil) is never going to be very high. Oil that is very expensive to produce, such as deep sea oil, very likely will not be profitable except at a price which puts the US economy into recession.

There is a fairly long lead-time on new projects—typically six to 10 years—so one knows a to some extent how much oil is likely to be available in the next few years.

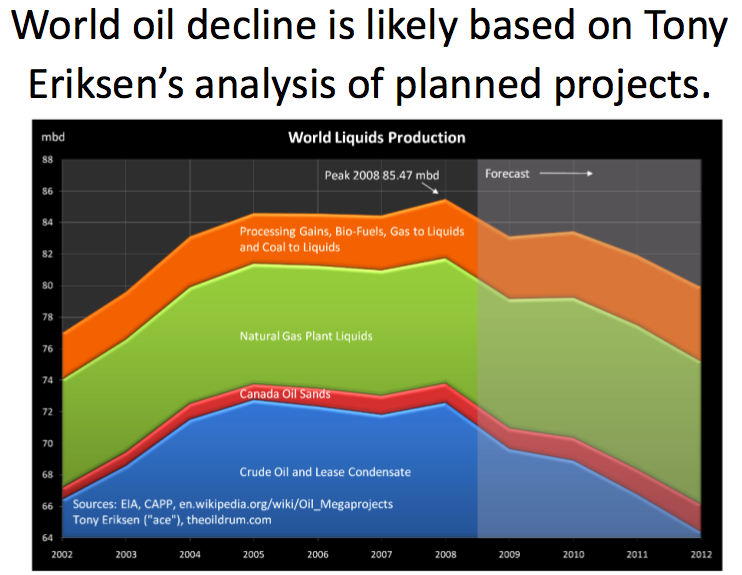

Tony Eriksen (ace) shows his forecast in Figure 16. Other analysts using a similar approach get somewhat different results. But even with more optimistic assumptions, this type of approach seems to indicate that world oil supply will be at best flat—or perhaps declining just a bit in the near future. If there is a huge improvement in technology, or a much higher level of investment, things could theoretically get better, but so far there doesn’t seem to be any indication of this. Investment is in fact down.

The problems we are seeing today in terms of recession and reduced credit availability are precisely the kinds of impacts we would expect to see from oil flow that does not meet society’s needs at an acceptably low price. While one cannot prove that our current economic problems are mostly related to the oil situation, it is hard to believe that the relationship could be happenstance. Even the crazy build-up in mortgage loans prior to the collapse may have been a way of disguising the real lack of growth in the economy, as world oil production stalled.

Going forward, it seems likely that the economic situation will generally trend downward, from the level we are currently at. Figure 10 showed that the increase or decrease in GDP tended to rise or fall with oil production. In Figure 10, the percentage increase or decrease in GDP tended to be somewhat higher than the percentage increase in oil production—but the graph relates to a period when debt was increasing. In a period of decreasing debt, one would expect the relationship to be more adverse—more downward trend in GDP for a given reduction in oil production.

In addition, if debt is decreasing, the price of oil is likely to stay on the low side, because of reduced consumer demand (layoffs and inability to by cars and new houses). The low price will make it difficult for oil companies to generate revenue from cash flow to use for investment, leading to less investment. The low prices will also discourage investment in places where oil is theoretically available, but the cost of extraction is too high.

I mentioned earlier (Figure 9) that above $80 or $85 a barrel, the economy tends to go into a recession. This is likely to be a barrier to developing much of the remaining oil resources. While there are a lot of resources in the ground, very little of it is easy-to-develop liquid crude. Most of it is in a tricky location (such as polar or very deep sea), or is a semi-solid that must be melted, or requires very specialized refining.

It is not clear that the $80 or $85 barrel threshold will remain either, in terms of being difficult for the economy to withstand. With reduced credit (still paying off old debt, but unable to obtain new), buyers will be less and less able to afford products made from oil. It is possible that the threshold for economic problems will occur at even a lower price level for oil—say $60 or $70 barrel.

I mentioned that credit is tied in with a huge amount of our economy—including our monetary system and our international trade system. So far, credit is down a little, but it still has a long ways to go. Also, while credit is down, the system is still holding up pretty well. The concern I have is that as oil production declines, it will be more and more difficult for the credit system to hold up.

For example, the US is buying oil on credit, because it does not have exports to pay for its imports. This has been going on for years, leading to more and more debt. At some point, it seems like this situation has to stop. Some exporter is going to catch on to the fact that we are likely never are going to pay our debts and change the system—cut off credit, or require that we offer needed goods in return—say a certain amount of wheat for a particular amount of oil.

If problems with international trade develop, they are likely to have a hugely negative impact on manufacturing of high tech equipment. Think about what is required for something as basic as a computer—petroleum to make the plastic case; several kinds of metals; a factory set up with precision equipment. Keeping the whole manufacturing system going requires a steady stream of imports from around the world.

Eventually, it seems likely that we will have to move back to a system similar to that of many years ago, where food is grown locally, and goods are manufactured locally, with local materials. It is not clear how much of modern transportation can be maintained—we may need to look at methods used centuries ago.

Why didn’t anyone tell us about this problem?

Common sense tells us that at some point, a finite world is going to run into limits. M. King Hubbert predicted the problem in 1956. A year later, 1957, Rear Admiral Hyman Rickover spoke about the problem:

I suggest that this is a good time to think soberly about our responsibilities to our descendants - those who will ring out the Fossil Fuel Age. Our greatest responsibility, as parents and as citizens, is to give America's youngsters the best possible education. . . . We might even - if we wanted - give a break to these youngsters by cutting fuel and metal consumption a little here and there so as to provide a safer margin for the necessary adjustments which eventually must be made in a world without fossil fuels.

The fact that resources were limited was known, but there seemed to be reasons not to bring up the issue. M. King Hubbert wasn’t really believed until after US production began to fall in 1970. And even if he was believed, with such a distant event, it probably seemed likely that technological advances would increase the amount of oil that could be quickly and cheaply extracted, for many years.

Also, it seemed like there would be other energy sources that would be able to replace our current energy sources. But so far, none of these is working out very well. Natural gas recently has looked like it may have potential to be a temporary partial solution, but even this is “iffy”. It may very well prove to be equivalent to $150 oil—more expensive than we really can make use of.

There have been many other energy ideas that have been looked at as well (biofuels, wind, solar, hydrogen, wave, etc.) but none is really a very adequate substitute for oil, and all are expensive, especially when one considers the entire “package” of upgrades that would be needed to make them act as a substitute for oil.

One would think that a magazine like Scientific American would bring this issue to the American public, but in recent years the magazine have tended to bring the public fanciful solutions, without pointing out the difficulties of these solutions. Their latest is in the November 2009 issue. My analysis can be found here.

There are two major organizations that forecast future oil production---the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). Both put out rosy forecasts of future oil production, year after year, even though the problems have been plain for quite a few years to anyone who looked at the situation very closely.

The UK Guardian published an article recently called “Key oil figures were distorted by US pressure, says whistleblower.” The article says that indications have been distorted under pressure from the Americans, and one senior official is quoted as saying, "We have [already] entered the 'peak oil' zone. I think that the situation is really bad." Similar reports about IEA distortions have been reported elsewhere.

If the IEA has been pressured by the Americans into giving overly-optimistic numbers, one can only guess that as much, or more, pressure has placed on the US organization, the EIA. The result is the very optimistic numbers published widely, and frequently cited to show there is no problem.

One factor that has helped to confuse the matter is the optimistic reserve numbers published by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). These reserve amounts are unaudited, and are quite likely overstated. Over a long enough time frame (hundreds of years) and at a high enough price, these numbers are perhaps correct, but it is very questionable whether OPEC can really ramp up production hugely in the next few years—or that they would want to, if it is clear that some of the world’s buyers really are not very credit-worthy.

Most of the analyses regarding oil production from the “peak oil community” have looked at the future decline in oil production strictly from a geological decline point of view. Geological decline is part of the issue—how much will production drop because the oil that is extracted is mixed with more and more water, and it is not possible to bring sufficient new production on line to offset the decline?

But, in my view, an equally big question is how much economic factors will influence future production. Will the international credit situation hold up adequately? Will lack of credit keep prices so low that investment in new extraction is greatly reduced? Will buyers of homes and cars be in sufficiently good financial condition to keep demand for oil and other products up? None of us really know the extent these factors will affect production, so it becomes difficult to have good numbers to give the American public.

The Task Ahead

There are many views of the task ahead. Some think more research is the answer, or more nuclear, or improved electric transmission plus wind turbines, or electric trains. To a significant extent, these views depend on a person’s view of the timeframe involved, their analysis of where we are now, and their view of how much or how little international trade will be affected in the years ahead.

My personal view is that the main task we should be focusing on now is how to move to a much simpler system—one that depends mostly on locally grown food and locally manufactured goods. This will likely mean a much lower standard of living. Limiting population should probably be a goal, because it will be easier to have enough for all if there are fewer mouths to feed.

I do not see climate change legislation as terribly helpful. Cap and trade will add huge overhead to the system—something we really cannot afford right now. Peak oil is likely to mean a continuing major recession, and a natural decline in fossil fuel use. To me, we would be better off spending our resources developing local agriculture and local manufacturing, and perhaps even sailing ships.

Thank you, Gail, for an excellent overview.

I’d like to share some thoughts about your bringing up “economic factors.”

Re: “But, in my view, an equally big question is how much economic factors will influence future production. Will the international credit situation hold up adequately?”

Here’s a link to some good discussion on this topic: http://www.energybulletin.net/node/50573

Re: “Will lack of credit keep prices so low that investment in new extraction is greatly reduced? Will buyers of homes and cars be in sufficiently good financial condition to keep demand for oil and other products up? None of us really know the extent these factors will affect production, so it becomes difficult to have good numbers to give the American public.”

It does seem quite possibly to put some numbers on, for example, how much “conservation” (by whatever means, i.e., how much drop in consumption) is necessary to have a particular effect. For example, lowering consumption by X % (some specified amount) delays peak by an amount one can quantify.

So, actually, it seems to me that putting some ranges and “ballpark” numbers is possible, and that this might be helpful.

One very important point to address is that peak means “the most” – the highest flow rate we can possibly have, and the most available quantity of useful energy.

...the most ability to do useful work, the most ability to make move now that will at least “avoid the worst” as the economy and available energy continues to shrink in total.

(Of course, there may be plenty of any one “thing”, even oil – if and only if one has the ability to pay. But the "ability to pay" is what is decreased as the effects of shrinking supply kick in.)

Regarding the impact of credit problems, at the far end of the range, the majority of international trade disappears and a lot of economies collapse.

By the way, the article you link to is an Oil Drum article that was reprinted by Energy Bulletin.

http://europe.theoildrum.com/node/5917

Great summary, but there's a distortion that creeps into production figures. The growing contribution of biofuels (Gail's figure 16) is an illusion, because that fuel is counted twice - once as the ethanol or biodiesel that flows from the production facility, and again as the oil that went into producing the feedstock. In the case of corn ethanol, we count fuel flowing from the distillery and also oil at the wellhead. Some of that oil went into powering seed and fertilizer deliveries, tractors, combines, trucks bringing corn to the distillery, transporting the product thousands of miles, and some other uses. Other fossil fuels contribute to the process too, so that at the end there is no gain in net energy available to power the economy. The energy return on energy invested (EROEI) is neutral. A similar but smaller distortion creeps in when difficult-to-extract or difficult-to-refine oil is counted in the same way as free-flowing mideast oil. The lower EROEI isn't reflected in raw production figures.

We need some way of reformulating production figures to measure net energy available to the economy, not the volume at the well or the distillery. Accurate figures would show less growth in production over time, or even a decline when the total production looks as though it's holding steady.

In the end, a declining resource base is consistent with a reasonable standard of living only if accompanied by a declining population. We know the social policies that result in declining populations, and they are better than waiting until nature makes the population decline for us.

Actually, the bad EROEI reflects in increased demand for oil. There will come a day that oil is needed, not for energy use but for plastics, lubricants, pharmaceuticals, and other products. At that time, even negative EROEI will be okay, since its use is not for energy. Again, this will drive up demand and cost, but if the products are sufficiently important to justify the expense, that is not a problem.

Wrong. Completely wrong. First thing, you can't have negative EROEI. An EROEI of 0 (zero) means you have to use infinite energy to extract what ever little bitty bit you get. Secondly, look at it simplistically. Imagine a well that produces just diesel - pure diesel. You can put it straight in a diesel engine and run it. OK, so you use a diesel engine to pump the diesel out of the well. Now, if you have to put a gallon of diesel in the pump tank and you pump two gallons of diesel out of the ground all is fine EROEI is 2. You have a gallon to sell. What if you only get 0.75 gals of diesel out of the well by using a gallon in the pump? (EROEI < 1). You use a gallon of diesel and get 0.75 gallons back. Put that in the pump and that 0.75 gallons will only get you 0.56 gallons of diesel to put in the pump. You can see where this is going, can't you.

Once EROEI drops to 1 it is game over. Cap the well and walk away. Yes, you could divert product from other uses to keep making pharma, plastics, etc - but how long would that last? And EVERYTHING else would stop. No cars, no delivery trucks, no agricultural tractors, and on and on. The whole thing would unfold pretty quickly.

I think all he is saying is that in a hypothetical future where oil is depleted and we've somehow made the transition to renewables (I am not making a judgment on the likelihood of a successful transition), it will still be possible to make products from oil with EROEI < 1.

Yes, but at that point the oil is no longer being used as an energy source but more as a resource like an ore or a mineral. We don't worry that iron ore is an energy sink because we don't use iron as energy. If/when we use oil solely as a non-energy ingredient in other products, we won't care about EROEI. Instead we will care about PROEI (Product Returned On Energy Invested), just like with iron ore, etc.

You shouldn't confuse the energy source for the investment as having to be the same as the energy yield. The energy return from a coal fired power station is well under 1 but is still quite profitable. Technology may still deliver new ways to extract large amounts of oil even if the EROEI is lower than one. I don't believe it is likely to happen soon and it won't be cheap, but sub 1 EROEI is not that last word for oil extraction.

I don't want to confuse the EROEI debate but here's a little reality check. First, EROEI has never been and will never be a part of the decision process to determine if a well is drilled or produced. At least not directly. Those decisions are made on a monetary basis. Of course, monetary evaluation is related to the cost in/revenue out relationship. And there is a weak link to EROEI embedded there.

It takes very little money/energy to produce most wells compared to the cost to drill and complete. Just consider that the average oil well in the US produces less than 10 bopd. Those wells kept producing when oil dropped to $38/bbl. And as long as an operator nets $1/month from all his wells he'll keep producing. I've even seen operators produce wells for a period of time at a loss. Consider that producing a very marginal well and netting $1/month is much more preferable to spending several thousands of dollars to plug and abandon it. And then you also lose the lease that you (or someone else) might want to drill on in the future. Feel free to continue the debate on the EROEI of producing wells but understand it has little relevance to what actually happens in the field.

Drilling new wells is a completely different matter. Now we're talking much greater energy consumption but more importantly much greater capital costs. We've discussed many times how to amortize the EROEI of the equipment involved in drilling well. No one has yet come up with a practical solution. From an industry view the equipment is a sunk cost so the EROEI is also considered sunk. The actual fuel utilized in drilling a well is rather small compared to the total cost (on the order of 5% or less). In 34 years I've never seen a well not drilled because the cost of diesel got too high. The two biggest components are the rental on the drilling rig and the steel casing used. There is an EROEI embedded in the steel but again how can you calculate that? And if you could make all those calculations what would it matter? I would say 99.99% of the folks making those decisions have never heard of "EROEI". In fact, that may be optimistic: I'm the only one I know in the oil patch who understand what those initials stand for.

Again, this isn't to say that EROEI discussions aren't academically interesting but they have no bearing on what will or won't get drilled. Like it or not, it's the profit potential that turns the bit to the right.

Cap and trade will add huge overhead to the system—something we really cannot afford right now. The rest of the article seems to be saying that free markets cannot get it right; the oil price has increased more than facts on the ground can justify then again it may also decrease even as supply declines. However carbon auction revenue will create cash flow that can be plowed back into investment in alternatives to oil. Think of it as a compulsory retirement plan for a commodity. That investment may never be enough but it could make the transition easier.

Let's say oil goes back to $50 and millions of people rush out and buy SUVs because 'things are getting better'. However it's a mistake whether the oil price is high or low because it's running out. Carbon charges (tax or permit auction sales) can be used to fund alternative transport that uses less oil. People will be better off than otherwise because of that forced investment. It won't happen on its own, just look at GM. Without forced carbon pricing we will continue to take the low road when we should be on the high road.

A tax is something different from cap and trade. A tax I can live with. It is cap and trade that adds too many costs to the system.

Gail,

I tend to agree with you for reasons that should be obvious-a tax is simple to administer, and the legions of bloodsuckers (accountants and tax lawyers) are already in place.Cap and trade will in evitably result in some very undesirable unintended consequences when we hit the cap part.

A straight up tax on carbon, combined with increased taxes on energy consumption,would result in less uneconomic investment and a more stable business environment.

We have more than enough bueracrats competeing for turf as it is.

I don't have the time to compose a long comment trying to explain my argument but an example may suffice.

When a supervisor tells a crew exactly how to do a job, rather than that a job needs to be done, his instructions stand in the way of making all the changes, large or small, that the crew can make in getting the job done.

After a while everybody's hands are essentially tied because there are so many rules that any serious change in the way the jib is actually done is impossible while at the same time a lot of sweat and talent and ENERGY AS WELL may be wasted in playing the game.

I agree. Cap and trade is just smoke and mirrors for BAU.

I admit that I don't know much about the cap and trade.

I'd be grateful if some people would actually explain what exactly it is and more importantly why they hold opinions that it is a bad (or good) thing (e.g. Gail mentions "too much overhead") and Zaphod42 calls it "smoke and mirrors for BAU".

In both cases however, I just really don't understand enough about cap and trade to be able to see why it has "too much overhead" or why it is "smoke and mirrors for BAU".

So, I'd be really interested in seeing explanations of this, as well as more opinions on cap / trade versus tax (hopefully with enough background to back up these opinions).

Pic

According to wikipedia,

There are a lot of practical problems with the system. Unless the total amount of the cap represents a reduction, it doesn't end up doing anything at all. The allocation to company of the caps is likely to end up not being very fair, because some favored industries will get a disproportionate share of the emission permits. Even if industries (such as cement) are hit by the cap, the legislation is likely to be written in such a way as to give other benefits to offset the cap. The whole thing becomes a political football that middlemen favor, because they make money on it. If a method of monitoring and enforcement is not put in place, companies may disregard the caps. If legislation is not written correctly, it ends up encouraging imports from China, which doesn't have such caps.

These are some comments from a WSJ article:

Cap and Trade Doesn't Work

Gail, your bullshit detector is broken(again).

The Wall Street Journal is cornucopian to the core and

Scientific Alliance is a GW denier front group.

In 2001, Foresight Communications helped launch the Scientific Alliance which claims to offer a rational scientific approach to the environmental debate "in response to the growing concern that the debate on the environment has been distorted by extreme pressure groups". The Scientific Alliance is a UK-based organisation of industry-friendly experts which states that it is "committed to rational discussion and debate on the challenges facing the environment today" [1], and populated by many of Britain's most prominent biotechnology enthusiasts and climate change sceptics.

http://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php?title=Scientific_Alliance

I'll be happy to debate Cap and Trade but I don't want to debate deniers

and think-tankers because they're intellectually dishonest as you can see by this plum.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emissions_trading

As you can see it would take forever to address all the misleading and untrue statements of these WSJ opinionators.

I would be nice to turn over the GW problem to a philosopher-king or world dictator but frankly this cap-and -trade, market dealie is the closest thing to reality we've got.

No B/S detector necessary for your ridiculous post-the smell carries for miles. Look, 5 years ago the Wall Street Journal would have been aggressively promoting Cap and Trade scams-obviously they realize Wall Street has pushed the whole mess too far too fast and they are trying to position themselves accordingly. If the Wall Street Journal states that Cap and Trade is a scam, that in itself is notable-that paper has never attempted to be a watchdog.

You don't understand Cap and Trade and therefore you hate it.

As a public service I once again post this in the vain hope that you will comprehend it,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emissions_trading

If the WSJ, which you otherwise distrust, says Cap and Trade is a scam then you find it to be notable.

Your brain has malfunctioned so you rely on knee-jerk instinct.

If you don't use your brain regularly you'll turn into a 'conservative'.

What a joke-that page reads like an advertisement for the wonders of mortgage backed securities circa 2005 (more liquidity, less risk and a magical AAA rating!). Bizarro World is here when Wall Street looting is promoted by those who hate "conservatives"-wild.

Enron Redux.

I think Cap and Trade is a great idea in theory but in practice it will certainly become just another casino to be manipulated and skimmed by the Wall Street organized crime ring.

It also seems like it would be difficult to determine allowances and that cheating in the assignment process would be rampant.

Like I said good theory but no way every one will play nice.

On a related note; Once a society crosses the line of integrity necessary for trust in business practice it is probably not going back.

I have watched ethics decay for the 20 years that I have participates in the US economy and this last episode looks to me like the nail in "Mutual Trust's" coffin.

I don't know about any one else but I have zero trust for any other when it comes to money.

As someone whom has to work with a cap and trade system (in the case of SO2 and NOx), there are a couple of key components. In reality it depends upon whether you can get comfortable with all the (moving) parts.

First, is the cap itself and how it is initially allocated (meaning who is included and how much do they get). Establishing the cap is relatively easy...how many Tg or metric Tons under the cap and, in the case of GHG's what factor is used to convert to CO2e (CO2 equivalent) for the various GHGs.

The allocation is where the fight is in terms of "fair share." Life gets interesting as teh overall cap is ratcheted down. It's one thing to do that at the state, regional, or even national level. It gets much more challenging at the international (global) level).

Second, how and who is to measure it. For some source categories and processes this remarkably easy. For coal fired power plants, where coal characteristics vary and where it is more difficult (though not impossible) to accurately measure the coal flow, you need only two values, the stack velocity and the concentration. Since the cross-sectional area is fixed at the point where velocity is measured, you can directly convert these two values into mass emissions. The addition of carbonate-based SO2 scrubbing adds to the CO2 load from a power plant.

Liquid and gaseous fuel are even easier (since their consumption is much easier to measure and their characterisitics are less likely to change greatly over short-time frames. Periodic confirmation of their ultimate analysis is all that is needed. The assumption (and it's a valid one) is that all or nearly all the carbon is converted. Other GHGs (like NOx which has a pathway to N2O) can be measured and accounted for.

A similar situation exists for liquid transportation fuels.

Other processes get a bit more difficult. SOCMI and petroleum refining are two examples where measurement and accounting get quite a bit more complex.

Third, accounting and trading. For cap and trade, there has to be some central repository for validated emissions data and a mechanism set up that looks a lot like a banking accounting system. What's on deposit (your allocation), what are your withdrawals (your emissions) and what credits (left over or available from some other source that is not using their full allocation). Some degree of market mechanism can set the price for trading a unit of allocations.

For those that argue smoke and mirrors...its based on the same principle as a checking account and if you have a checking account, then you are arguing that your checking account is "smoke and mirrors" (which begs the question: why do you have a checking account?).

Turning to the tax alternative with a tax...it is simpler and except for racheting down the cap, there is no real incentive to lower (and to trade) allocation units of GHGs. The issue becomes one of just passing that cost through and if exceeds the allocation what happens next (what penalty do you impose? 100% of net profits? 100% of gross revenue?)

Both systems have issues to deal with, but given our recent experience with some market-based bubbles, it is easy to understand why C&T looks like something to be suspicious about.

Apparently, even the Economist thought that Cap and Trade for Sulphur Dioxide was a great success !

"Cap and trade" harnesses the forces of markets to achieve cost-effective environmental protection. Markets can achieve superior environmental protection by giving businesses both flexibility and a direct financial incentive to find faster, cheaper and more innovative ways to reduce pollution.

Cap and trade was designed, tested and proven here in the United States, as a program within the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments. The success of this program led The Economist magazine to crown it "probably the greatest green success story of the past decade." (July 6, 2002). "

"What are the elements of a well-designed cap and trade program?

A successful market-based program requires just a few minimum elements. All of the following are absolutely essential to an efficient and effective program:

•A mandatory emissions "cap." This is a limit on the total tons of emissions that can be emitted. It provides the standard by which environmental progress is measured, and it gives tons traded on the pollution market value; if the tons didn’t result in real reductions to the atmosphere, they don’t have any market value.

•A fixed number of allowances for each polluting entity. Each allowance gives the owner the right to emit one ton of pollution at any time. Allocation of allowances can occur via a number of different formulas.

•Banking and trading. A source that reduces its emissions below its allowance level may sell the extra allowances to another source. A source that finds it more expensive to reduce emissions below allowable levels may purchase allowances from another source. Buyers and sellers may “bank” any unused allowances for future use.

•Clear performance criteria. At the end of the compliance period (e.g., one year, five years, etc.), each source must hold a number of allowances equal to its tons of emissions for that period, and must have measured its emissions accurately and reported them transparently.

•Flexibility. Sources have flexibility to decide when, where and how to reduce emissions."

http://www.edf.org/page.cfm?tagID=1085

But sulfur dioxide is very different. You buy a scrubber, and you get rid of your sulphur dioxide problem. There is nothing equivalent for carbon dioxide.

So, what I hear you saying is if it's a cheap and easy band-aid, and can be done without much disruption to this quarter's profits, folks will do it. If it's difficult, requires thought and innovation, and maybe costs more, in the short-term, while offering a long-term benefit, it's not worth considering.

So much for putting a man on the moon...I find it a rather sad reflection of today's corporate mindset.

For sulfur dioxide, there is at least a reasonable fix available. For carbon dioxide, we have been working on fixes, and what is available is pretty minimal. Biochar is nice, but the amount of plant residues to turn into charcoal is pretty minimal compared to fossil fuel use. Cheating would seem to be an option for some. Using up our natural gas to replace coal is an iffy solution at best--what do we do to balance wind, when we have used up our natural gas? Natural gas has a whole lot of other valuable uses, as well.

Thanks Gail,

For digging up the quotes and your explanations.

It certainly sounds more complex than a "simple" tax. So I can see why their might be a greater overhead (and potential for abuses is probably also higher in a complex system).

As to the claim that it might encourage "imports from China, which doesn't have such caps". How would that be any different for a tax? Wouldn't a carbon tax also encourage imports from China which doesn't have such a tax?

It seems to me that taxes also have potential problems (just like Cap & Trade, I guess it depends precisely on the details of how the tax is charged, exactly on what kinds of activities / products it is charged and how high the tax is).

My criticism on a tax is that it looks to me that it is very hard to use a tax to actually hit specific emission targets.

The question is... How high do you have to set the tax to limit CO2 emissions to X tons / year?

Moreover, if people are willing / able to pay the tax, then they can produce as much CO2 as they wish.

My feeling is that the taxes are usually set too low to really make a difference, so they will have very little impact on actual CO2 production. So to me a CO2 tax looks like a typical government action: do something that looks merely like it is doing something, while BAU just continues. Then later on act surprised that it didn't actually reduce emission to the targets.

A cap and trade however does have an actual *cap*. So a hard limit (assuming that it works) can be set on CO2 emissions, and market forces (supposedly) then make the price go as high as it needs to go to meet keep that cap from being exceeded.

Pic

I guess with all of these things, the devil is in the details.

The administrative cost/ middleman cost of a cap would seem to be a lot higher with cap and trade than with a tax. That is part of what makes it so popular with the would-be middlemen.

As you point out, a cap could be set at a selected target and hit it. I think as a practical matter, it would tend to overshoot on the downside, because of the connections in the system. For the most part, what are being capped are sources of energy. If you put on a cap on carbon, and if GDP is really closely tied to energy use (Figure 11), GDP will go down as well. Declining GDP will cause credit to unwind further, encouraging GDP to go down further. So you will get even more of a drop in energy use/ GDP than expected. None of this will make the population happy.

A tax would be harder to raise over time. The excess portion would need to be rebated back, so it would just be a matter of shifting of where the tax dollars come from. It seems like a tax could be adjusted to hit a selected carbon target, but it would be more difficult. With a cap, you at least have the illusion of heading toward a target; with a tax, it is really uncertain.

Unfortunately, it is true, the devil is in the details. So I fear that we are simply lacking the political will to implement *real* (and painful) measures that actually make a difference. So my guess is that no matter what, tax or cap and trade, we will just end up with policies that are ineffective and just "smoke and mirrors" for BAU.

Dave Cohen thinks "The Oil Situation Is Really Bad":

http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/HL0911/S00159.htm

PLEASE, could peak oilers start using the phrase 'oil extraction' rather than the misleading and inaccurate term 'oil production'. Part of the preparation for living in a finite world is to change our vocabulary to reflect reality. Richard Heinberg can do it; I do it, so why can't everybody else do it?

And while I'm on the topic, I suggest that we stop referring to 'depleted' oil fields as 'mature', which is another euphemism in the language of denial.

Better yet: instead of oil "production," how about oil "confiscation." Nature produces it, we just take it.

Instead of "mature" oil fields, call them "dead" ones.

Certainly historically oil extraction is the more accurate term. However, with tar sands, biofuels, heavy oils and CTL and GTL coming on stream then 'oil production' begins to reflect reality. We are producing oil using a feedstock which itself is grown or extracted. The sting in the tail is that production processes have sub-unity energy returns. You get less energy out than you put in in feedstock.

There are so many negatives from extraction from tar sands, biofuels and shale that it is difficult to list them all. Low EROEI, wasted water, using natural gas as a fuel for heating it [IMO NG is as vluable and more vulnerable than oil], ecological degradation... the list goes on and on.

The we hear about Trillions of barrels available... feeding into the fossil fuel propaganda, and digging the rabbit hole ever deeper.

Unless and until there is a reliable alternative energy source that can be used, a method that does not deplete fresh water sources, and an ecologically friendly way to mine the stuff, it is just imaginary oil. And, if we have the alternative energy source, it is probably not needed except for the other oil uses, and can be extracted and produced in a slower and more acceptable way.

I would suggest that you use "oil depletion" rather than "oil extraction". If I can get picky, extraction can give someone the impression that we can still store it somewhere, perhaps indefinitely. Depletion reflects reality much better in describing the overall reduction. I do use extraction but only for the technical definition of removing it from the ground. Maturation of fields is another technical term that is very useful for modeling. So I am not really sure what your beef is.

Web -- I had passed on the chance to enter the terminology game but since you're out to pick a fight I'll team up with you. I don't really have a problem with the view Martin and Ann express other then how it can make our positions with the deniers weaker. Perhaps they were just venting their frustration some and aren't completely serious. This gets back to the point I made a while back how PO proponents inadvertently give ammo to the deniers. If you say a field is "depleted" instead of "mature" then the deniers will throw that field's current production right back in your face and discredit you. A mature field is a producing field. A depleted field is a field no longer producing. A simple enough distinction for even Joe6Pack to grasp. Tell J6P Field A is depleted and the deniers come back with that day's production number and you've lost that battle. Same goes for "mature" vs. "dead'. As far as "production" vs. "confiscation" goes I'm sorry Ann (I do get your emotional point) but such usage will have 99.9% of the J6P's out there throwing you into the tinfoil hat crowd IMHO. And that will surely hurt our cause.

Hi Rockman, WHT

I must agree with you guys about the terminology but the opposition has a point.

In our language the term mature may be interpreted in several ways that are capable of mis application ,misinterpretation, and the deliberate confusion of the issue.

Just look at the amount of smoke the creationists are able to generate out of the various valid definitions of "theory" by pretending there is only one definition of the word.

In biology a mature (young ) woman or man is one old enough to leave the family household and start thier own family-putting them at the young end of thier productive life.A person exhibiting mature judgement and opinions is not implicated as being in his dotage-just the opposite.

We might use the words "aging " or rapidly aging" or "middle aged "in describing oil fields in non technical discussions to good effect."Middle aged" is a term that is on the minds of many tens of millions of people and it carries just the right faintly doomerish tone-things are ok FOR THE MOMENT but tomorrow may bring anything from the death of an older friend or relative to our own heart attack or stroke.We need not harp on the inevitable decline that follows middle age- the Harleys and plastic surgeons are proof enough that the word hits home hard and low.

And if some cornucopian wishes to take issue with the "rapid ageing " of some particular field that is in obvious and documented decline he will win only the audience is composed of real fools- not just the public, which is not really so much foolish as uninformed and complacent.

We really are "designed" to live in small bands or troops and to let a few alpha individuals run things for us.We want to listen to the message coming down from the top.Listening to the dissidents is dangerous-always has been , always will be.We recognize this truth in our bones.

The alphas have morphed into the "they" who the common man speaks of , meaning the govt and uber powerful unseen individuals and cliques of such individuals-and the large majority of us are satisfied that this is exactly as the way things should be-this is the normal state of affairs for our species.

Don't bother me boss I'm just another little ape doing my own little ape thing.I don't want to stand out-I want to stand in -just so long as I am standing in a high status clique.

If ever we find ourselves living under the thumb of a Stalin or a Hitler -something that cannot be absolutely ruled out-we rabble rousing agitator types will be in a slave labor camp in very short order.

And I'd have to agree with the two of you in concept but completely disagree on the terms you've settled on. For most of us outside your field, "depletion" means nothing. The only "deplete" most of us have heard of is "depleted uranium" - those are the big bullets that the military uses when they really want to mess up a bad guy's tank.

And "mature" runs into similar problems. For you folks in the field, it means the field is slowly headed toward being shut down. For most people, mature means that you've finally grown up, and are now better in just about every way than you were when you were younger. The baby boomers are also playing an Orwellian game with the term, so now mature also applies to seniors, and in *no way* implies that you're in decline *in any way*! So if you tell J6P that a field is mature, that means that it's doing the best it has ever done!

I'm not sure there are good terms to use for this. Most people don't accept the concept of slowly declining performance. For most things, they expect something to run mostly like new and trash it when it stops doing that. Cue one of Nate's articles on how our perception of aging causes cognitive dissonance here...

Mature and aging are physiological terms. How about just saying the field is "at peak" or "post peak?"

Excellent point clark. We do tend to not hear ourselves as outsiders do. I recall a story from 30 years ago when a educated fellow could see a problem with storing 100's of millions of barrels of oil underground at the SPR. Eventually those barrels would rust and the oil would leak out. When I see the word "barrel" it's automaticly a volume...not a steel drum. I'm no sure with all the different interests competeing for the attention of Joe6Pack we'll ever have a useful nomunclature to work with.

I wouldn't worry so much about the terminology, guys. Peak Oil is a complicated subject. There are a lot of people who can not understand it no matter what, there are plenty of others who WILL not understand it no matter what. One is either willing/capable of putting in the work and study necessary to understand the subject or one is not. There is little point IMO to walk on eggshells around those who are hostile to taking a sincere and open minded look at the issues. And in the meantime, all you do is tie yourself in knots with self doubt about your own ability to explain the message. And at the same time, you run the risk of fogging your own thinking regarding those actions necessary for securing your own future moving forward.

Jabberwock

True, a lot of people can't understand peak oil and others are so biased they won't consider it. However, it is not because Peak Oil is complicated. Gail does a good job of simplifying Peak Oil in this article. Although, the economics part is secondary. I say secondary because most people who have yet to agree with Peak Oil can't, or won't, follow the economic part. Fortunately, I don't think it is even needed to convince others that Peak Oil exists.

I have a challenge to all TOD readers. Surely there is enough talent here to design a physical model of Peak Oil. Something that would fit on a card table and could be easily transported. It could be an flat model or a sphere representing the earth with oil fields, wells, and pipelines to a refinery. The system would contain a fluid representing oil. Small pumps move the oil through the system. The idea is to show what Peak Oil is, not define it with graphs.

The pumps would be programmed to move the oil from each well to the refinery to demonstrate how we reached peak oil. Some oil fields would be huge, others medium and small. The rate that oil is pumped would vary by field to represent what happens in real life. New fields, representing new discoveries, would come on line at different times. You can see the oil level in the fields going down. You could even have an oil field contain a substance that represents unrecoverable oil. The entire process night take about fifteen minutes. Just long enough for a speaker to tell the observers what is going on and how this model represents Peak Oil.

During the presentation the refinery on the table will be draining into a large container on the floor. That container represents oil consumed to date (not really important for this demo, but the oil has to go somewhere). The refinery is really a graduated container so people can see the how the daily production grows, peaks and then declines as the various oil wells come on line, production increases, peaks, and declines.

Has this been done? I bet it would be a fun project. Set up a few thousand of these in shopping malls across the country and watch the converts roll in;) Better yet, get it into our schools so our kids will ask their parents what the hell they are doing about the future.

Okay, I can already hear some of the problems with this, such as Peak Oil critics claiming this model underestimates the remaining reserves. That is not a big deal. What is a big deal is the point at which the oil level in the refinery container starts to drop. That will have a huge impact on the general public who this model is designed for. To counter the other arguments and misinformation, and the estimated reserve question, simply put together a brochure that, in layman's terms, debunks them. That brochure is also where the graphs go:)

And a second brochure can contain Gail's excellent thoughts on the financial aspects of Peak Oil. You just won't have to print as many of those:)

http://mobjectivist.blogspot.com/2005/06/part-i-micro-peak-oil-model.html

In terms of computations, most of these transitions are relatively quick so that you end up using the big hitter transitions of "fallow", "construction", "maturation", and "extraction". This is the diagram to the right.

1. Someone makes a discovery and provides an estimate of the quantity extractable.

2. The oil sits in the fallow state until an oil guy makes a decision or negotiates what to do with it. Claims must be made, legal decisions made, etc. This time constant we call t1, and we assume this constitutes an average time with standard deviation equal to the average. This becomes a maximum entropy estimate, made with the minimal knowledge available.

3. A stochastic fraction of the discovery flows out of this fallow state with rate 1/t1. Once out of this state, it becomes ready for the next stage (and state).

4. The oil next sits in the build state as the necessary rigs and platforms get constructed. This time constant we call t2, and has once again an average time with standard deviation equal to the average.

5. A stochastic fraction of the fallow oil flows out of the build state with rate 1/t2. Once out of this state, it becomes ready for the next stage.

6. The oil sits in the maturation state once the rigs get completed. We cannot achieve the maximum flow instantaneously as the necessary transport, pipelines, and other logistics are likely not 100% ready. We also do not know the reserve accurately so we plan proportionally to reserve. This time constant we call t3.

7. A stochastic fraction of the built rig's virtual oil flows out of the maturation state with rate 1/t3. Once out of this virtual state, it becomes ready for the next stage of sustained extraction.

8. The oil sits in the ready-to-extract state once the oil well becomes mature.

9. The oil starts getting pumped with stochastic extraction rate 1/t4. The amount extracted per unit time scales proportionally to the amount in the previous maturation state.

The nice thing about this model is that you can easily simulate it using state transition equations.

http://mobjectivist.blogspot.com/2006/01/great-curve.html

re: PLEASE, could peak oilers start using the phrase 'oil extraction' rather than the misleading and inaccurate term 'oil production'.

You're quibbling over semantics. Among the numerous meanings of production are: the act of bringing forth, presenting to view, bringing onto the market. It doesn't necessarily mean manufacturing.

Some oil companies I worked for used the word "exploitation" instead. If the shoe fits...

Thanks for beating me to the punch, Rocky.

It does seem to me that each and every one of the comments above indicate that the writer knew exactly what the term meant.

I would further suggest that unless you have greased, oiled, checked fluids, and started a flywheel engine, you might think the production end of the business is an easy process. And, sometimes it is. Other times, you have to keep working only to find that the points on the mag were burned but would still give you a bright blue spark when tested. And you find it after chunking a spark plug that cost you $8 out into the brush. Good thing those are big spark plugs.

Sometimes, I don't think "produce" says enough about the effort required.

Oh well, anyone want to help me wrench rods so I can "extract" some more oil ????

You may be mixing up cause and effect and oversimplifying. Yes GDP is correlated with oil price but that's partly because in a boom more oil is used and in a recession there is a cutback. While I'd accept that a price spike causes a cutback too, the short-term price spikes of 2007 were really caused by over-buying of futures contracts which then corrected the same year. But the reason everyone was buying into oil was because the debt level became unsustainable, the recession was coming, the stock market was diving and the pension fund managers stupidly thought that commodities were a safe haven. Inevitably the speculation corrected and the oil price dropped. The initial price rise from 2001 had of course been caused by the Iraq war and fears of supply.

Of course, we also have the reality that cheap oil allowed globalization by reducing shipping costs which then caused a slump in Western manufacture, so the Western GDP was then propped up only by rising house prices which were in turn based on cheap debt. And of course an economy that depends on house prices to continually rise is doomed to collapse, which is what happened. So it's all a bit more complex than your simple analysis allows for. In other words, correlation is not causation.

Indeed a higher price may actually be better for western economies because:

a) It makes cheap imports more expensive and allows local economies to redevelop their own manufacturing base, which gives real GDP growth from added value, rather than artificial growth from debt.

b) It encourages investments in extraction or gasification of shale oil and extraction of heavy oil, which are both hugely abundant - as even Hubbert noted - and which in turn ensures a future supply of oil.

Also perhaps a more important correlation is between the price of gold and the number of barrels it buys, which has hovered around 14 barrels per ounce for a century. So it's likely the variance in the price is more indicative of the value of the dollar than anything else.

Lastly, oil is largely used for transportation and plastics so a reduction in oil would not reduce electrical energy output hence it's not quite as drastic as you suggest. There is plenty of coal and gas to keep the lights on and there are also alternatives to plastics which could be used if plastics became expensive. So it's not all doom and gloom! It really depends on how you want to view things!

I was going to post a comment along these lines, I think there is a certain element of conflating cause and effect in this argument. How do you prove oil prices caused the recession rather than the recessions(s) caused a falling oil price? The answer is you cannot, it is pure conjecture.

It may not ALL be doom and gloom, but your counterpoints carry a recurring omission.

Regardless of the dollar's health, or the Gold price ratio to oil, or the amount of coal we can fall back on, is the central point that all of these things float on a system driven (almost entirely) by oil. Price will be a downstream effect of an oil downslope. This will hit prices of shipped goods across the boards, so this will hit utility prices as well, and food, of course, and people's rates for service, owing to their increased travel costs, or the increased cost of their supplies brought through the Petroleum transport system.

It does depend on how you want to view things, and it's really not all bad.. but don't turn a blind eye to the quick succession of causations that can cascade around the entire system with fairly benign-seeming hiccups.

Or in other words, what happens with a lowering tide? What out there do you really propose is immune from that, what is actually grounded already, and not floating on the Cheap-Oil Sea?

I think the issue is really Liebig's Law of the Minimum as applied to oil. Without alternate infrastructure, and with reduced oil availability, things stop working very well. It becomes difficult to, say, ship coal long distances, and its use declines as well.

I think the other issue is that if/when a decline in oil availability results in a credit unwind, the credit unwind results in a drop in demand for practically all goods and services. Prices of commodities drop, so it makes less economic sense to extract natural gas or uranium.

All of these things are likely to work together to bring about a cascading impact, but there may be occasional stops along the way, where things look better for a while.

I (more than) suspect that we will get some number of stair steps down but the system is much more fragile and brittle than many people believed before September 2008. Thus we are (in my view) likely to see what I'm calling the Early Staircase Model:

Any number of items could bring the whole system down:

Once the economy fails to the degree I expect, the systems that run our civilization begin to fail. That's because sometimes people think the financial system (which I'm using to represent currency, debt, monetary transactions, etc.) sits much higher on the dependency stack than it actually does:

I think we lose sight of how much we depend on the financial system. Even if "just" the international piece of it stopped working, we would find ourselves in a few years with many fewer goods to trade. Parts would wear out for cars, and we wouldn't be able to replace them. Computers would wear out, and we wouldn't be able to get new ones. Oil would be very much less available--and because of this, food would become in short supply. Even US oil would stop being available, if some necessary part in the supply chain were missing. Ditto electricity.

I think we're of the same mind.

The interesting question is whether we might be able to ever achieve even half the economic throughput we have at this point. At first glance it should be possible since we will still have many resources left even if not as much compared to when we started.

My guess is that, just as you point out below with the problem of leaving oil in the ground for our descendants (use it or it will become stranded), it's entirely possible that many, many other resources will become inaccessible at their current diffuse levels unless we have the astonishing amount of energy available now for the entire infrastructure.

Perhaps a good metaphor to use is that right now the resources are within arm's reach, roughly a bit above eye level. But in a collapsed economy, the resources will effectively become out of reach for us — simply too high to get even on our tippee toes.

I suppose that's why some science fiction stories often have us looking for metals at the dumps.

But what is the minimum?

You say without alternate infrastrucutre... but why can't we have alternative infrastructure?

Also, what about simple infrastrucutre changes? I live near Dallas. They are talking about implementing a street car system downtown. This is a matter of building trolleys and laying rails in the existing roads. How hard is that?

Then there is the switch from guzzlers to small cars, hybrids, EVs where nothing else will do, motor assisted bikes, etc. Dropping speed limits so that these options are safe. Using electric bikes.

What about moving closer to work? I work a part time job 80 miles away because it gives me future prospects. When I cannot afford this (which will be when my car breaks down) I will take a closer job, or move to the city.

What about converting those empty houses everyone wants to tear down into local stores for making subdivisions more walkable? Then, for necessary commuting, a park and ride bus system until we build more rail out for a park/bike and ride rail system?

These are things people will do when they can no longer afford to do otherwise.

My point is, who says the Leibig's Minimum is current production? I really believe that with a reasonable amount of electric power (coal and gas now... later more nukes and renewables and probably coal for a while) and plenty of places to extract syn crudes for plastic, plus the remaining half of oil reserves, we can maintain a very modern society for a while.

The question is, will we? I think so, once we must (soon). I see no reason for your absolute pessimism on this point.

The answer to how all of this works out depends on which constraints become important first. If it is lack of availability of imports, electricity is likely to become unavailable at virtually the same time as oil. If the constraint is price of oil, then electricity may be a viable alternative.

I think a lot of people assumed price of oil would be the #1 constraint, and built their mental models around it.

Now that we see firsthand the interaction with credit, it is not at all clear that oil price will be the big constraint.

Hi Gail,

re: "If the constraint is price of oil, then electricity may be a viable alternative."

Are you saying electricity may be a viable alternative because the price of NG would be lower than the "constraint" price of oil? Or, are you saying that other means of production of electricity could be put in place even with a high price of oil?

Anyway, one problem with electricity being available (or inexpensive) and oil not being available (or expensive) is the dependence of electricity production upon oil availability: People getting to work, roads being maintained, grid being maintained. And so forth. (Wouldn't you say?)

Aniya,

Quite frankly, I have a hard time seeing electricity not being a problem when oil is a problem.

I suppose there might be some scenario that could arise--say a breakthrough in natural gas, that would allow things to go along well, even though oil production was down, and prices high. But even this is iffy. As you point out, people have to get to work.

Perhaps I was being too generous in my response to Andrew in Texas. Since I can't see all possible outcome, I was trying to leave the door open a crack.

What is so generous about considering a poster's serious comment on your work? Was anything I said outlandish? It's not like I was suggesting we beam solar power from space to power intergalactic flight and PHASE II society or something. I think my comment was pretty down to earth, and you never really addressed it (either in the original post or in your response to me...). Is it just that I don't always agree with the prevailing ideology here that makes you think my comments don't deserve consideration?

Leaving the crack in the door would do us all some good... especially if it were more than a token gesture. I'm not trying to be confrontational (at least not personally so in an ad hominem), but you've posted several similar articles about Peak Oil and its interaction with the financial markets, and I always feel like you don't try to address your opponents viewpoints the next time around. Not that you have to be swayed, but the fact that you often don't address counter arguments makes me wonder how open your door really is. (Again, not trying to attack you, just the ongoing argument.)

Finally: Japan. Stagnating oil use. Increasing nat gas use. Been going on for a while, as documented on TOD. There might be an argument for energy use having to grow to maintain society, but certainly not oil use. I don't buy your minimum argument.

Andrew, re Japan. The fact that Japan is a very crowded small island in contrast to spacious US may have a lot to do with it.

Yes, it does make a difference. But don't forget, most of the spacious US is rather empty. It's really a collection of cities and suburbs.

The main difference is, our cities (most of them) are spread out. I don't think that's as irreversible as some people suggest. That was the point of my comments on light rail, park and ride, electric cars, bikes, etc. (I don't think we are all going to be driving electric cars. But maybe some. I don't think we'll have many hydrogen cars, but hydrogen buses? Hydrogen bulldozers and tractors? Maybe.)

That Japan is an island explains why it has crowded cities and is thus better situated, laregly by accident, to deal with peak oil. But we can centralize here too. Yes, the late start doesn't help, but there are things we can do (park and ride) to make the best use of our sunk costs.

My point with Japan was that there is no law that says: we need X amount of oil for civilization to do Y... unless you narrowly define Y (as an ICE individual transport society). But I am far less interested in the future of the Mustang than I am in the future in general.

Everything is so networked, that if oil goes, so does electricity--probably because oil takes down the financial system first through problems with credit. The fact the Japan imports its oil isn't really relevant. Oil is now available in the marketplace, and Japan can buy it, and a mix of other fuels.

If problems with the financial system don't take out electricity, problem with oil availability are likely to take out the electrical system, perhaps a little later. Oil is used in all electrical systems--by repairmen, driving trucks and using helicopters; for lubrication; in transporting nuclear energy; in maintaining wind turbines; by workers getting to work. Japan will have trouble with electricity, like everyone else.

Hi Andrew,

These are interesting ideas.

re: "Also, what about simple infrastrucutre changes? I live near Dallas. They are talking about implementing a street car system downtown. This is a matter of building trolleys and laying rails in the existing roads. How hard is that?"

While I don't mean to be flippant - the question is yes, how hard is it? (Are you going to do it?) How much does it cost to do? Where do the funds come from? What is "not done" in order to be able to do this? Who makes the decisions?

I'm all for simple infrastructure changes. The question is: How? Who is responsible? In other words, who is the "they" who is "doing the talking"?

re: "These are things people will do when they can no longer afford to do otherwise."

When they can no longer afford to do otherwise, how is it they will be able to afford to do the wise thing?

With what funds? With what oil? (Take a look again at the graphs.)

That is a mouthful. Okay.

"While I don't mean to be flippant - the question is yes, how hard is it? (Are you going to do it?) How much does it cost to do? Where do the funds come from? What is "not done" in order to be able to do this? Who makes the decisions?"

Not hard. Again, it's a matter of laying rail in asphault. This is simply not that big a construction project (nowhere near the size of the other projects on the table, namely the commuter DART railline be extended from Dallas all the way to Lewisville or Denton... sorry if those names mean nothing to you... this is a LONG way up the I-35E interstate). I don't know the price, but I can guarantee you it is not that much or it wouldn't be on the table in a place like Dallas.

Will I build it? (Yeah, that one sounds flippant.) No, obviously construction workers will build it. What will not get done in its place? How about more highway construction. I don't really care what doesn't get done in its place, because this is more important. And the net effect on the local economy by this spending would be the same, or really better, because it would be restoring the downtown area to economic viability.