More natural gas controversy

Posted by Gail the Actuary on November 4, 2009 - 10:14am

Monday, November 2, Arthur Berman wrote in his blog:

Pressure from Petrohawk helps cancel World Oil column

In an act of extraordinary courage, a top Petrohawk executive threatened to cancel his free subscription to World Oil if the magazine continued to publish my column. Today, John Royall, President and CEO for Gulf Publishing, cancelled my November column.

I have accordingly resigned as contributing editor.

Heading Out (Dave Summers) and I have been talking about the issues Arthur Berman raises for quite a while now. Most recently, Dave wrote a post called Shale Gas Estimates Perhaps Optimistic - An Interesting and Worrying Talk at ASPO.

So what are the issues involved?

What Arthur Berman is saying is that natural gas companies that extract shale are mis-estimating how quickly natural gas production will decline in the future--they are assuming gas production will decline more slowly than evidence indicates it will. As a result of their optimistic assumptions about decline rates, they are assuming that shale gas can profitably be extracted for as long as 50 years, when Berman believes the average well life is only about 8 years.

Part of the controversy revolves about what price is needed for shale gas to be profitable. The gas companies are saying that natural gas is already profitable, or near profitable, at today's low prices. As Heading Out notes, Chesapeake testified before congress that the company could operate with a price of $4 per thousand cubic feet. Arthur Berman is saying that prices need to be much higher.

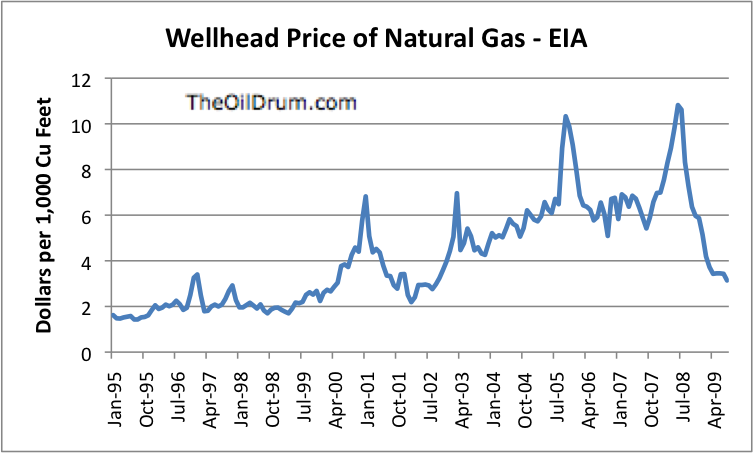

Berman puts the necessary price for operators to earn a reasonable profit at about $9 a thousand cubic foot. One can see from the graph that in the past, prices have rarely hit this level. If the quality of resources goes down over time, the necessary price could rise from this point.

Based on the analysis of Dave Murphy, we have seen recently that it is difficult for the price of oil to go much over $80 without it causing a recession. Natural gas is a smaller part of the economy, but I suspect it still has issues with too high a price being recessionary.

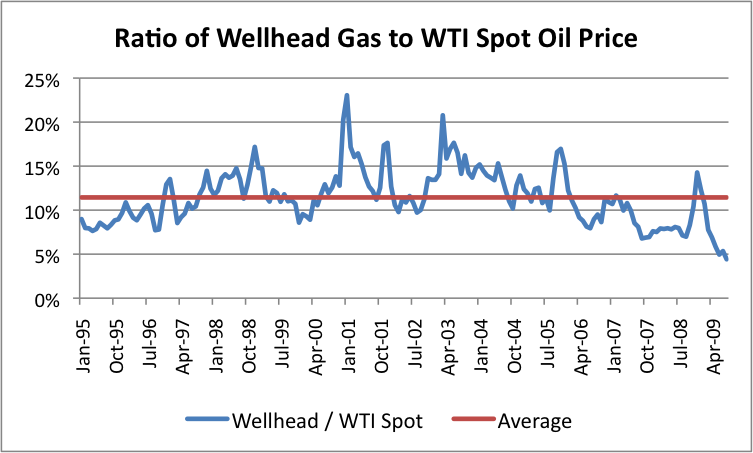

Historically, natural gas wellhead prices have averaged about 11.4% of West Texas Intermediate oil prices. If this ratio holds, one would expect the threshold at which the economy starts reacting negatively to high natural gas prices would be about (11.4% x $80) = $9.12, which is uncomfortably close to what Arthur Berman says is the necessary price for profitability of shale gas. Arguably, the average ratio could be distorted by the high ratios during the periods when there were natural gas shortages, but oil prices were quite low (2001, 2003). But if we choose a lower ratio excluding these points, say 10%, the threshold for gas comes out to (10% x $80) = $8.00 per 1,000 cubic feet.

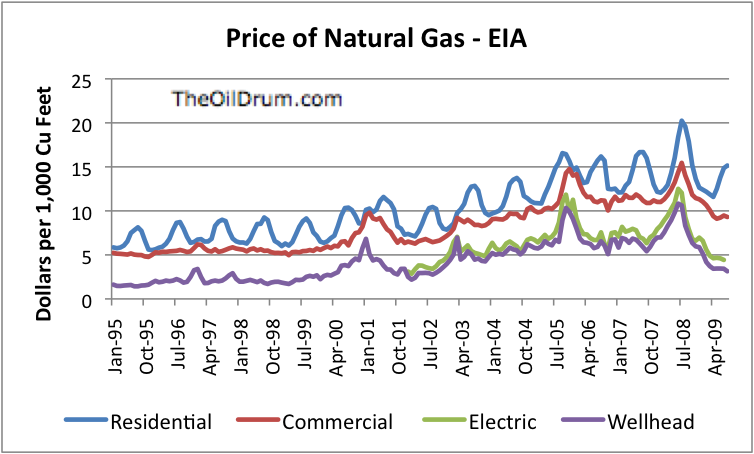

Arguably, the maximum price for gas should be about 1/6 of the price for oil, because its energy content is about 1/6 that of a barrel of oil. But transport and distribution costs for natural gas are higher than for oil, so perhaps the lower empirically derived ratios are reasonable. (The high residential prices during summer reflect the fact that little gas is sold during the summer, but overhead for the companies selling the gas continues. Also, many homeowners opt for level billing all year, to smooth out differences in the amount of fuel used in the summer and winter, and this distorts monthly price per BTU indications.)

There is a second problem with natural gas price. If one ramps up natural gas production, one has to simultaneously ramp up infrastructure for end uses (for example, natural gas busses and fueling stations) plus pipelines and storage to enable the new end uses. If one doesn't do this, the extra natural gas has nowhere to go, and prices drop precipitously. This is what has happened recently. Adding new infrastructure is slow and expensive, so this may mean that natural gas prices may languish for many years before production and infrastructure finally match (especially if the country is in a recession, and this holds back demand).

At this point, North America really needs to know how much natural gas is producible, and at what price, in order to make good decisions on infrastructure. It doesn't make sense to add a lot of natural gas infrastructure unless enough natural gas will be available, over a long enough period, to make the investment a reasonable one. If Berman's calculations are right, not only is quite a high price is needed, but the amount that can be produced is quite a bit lower than other estimates suggest. One really needs to know the right answer.

Obviously, there are individual company issues as well. If long term natural gas production from existing and new wells is expected to be very good, the value of a gas company's land is much higher. Natural gas companies can borrow more money against the higher value of the land, enabling new investment. The value of the stock is also likely to be higher.

Fortunately, whether or not Berman is writing about the issue, he has raised enough questions that one might expect auditors to be somewhat diligent about the issue this year end.

What are the some of the arguments against Berman's approach?

Berman, in his blog, quotes a rebuttal by Tudor, Pickering and Holt. This is an excerpts:

Technical credentials. In any technical discussion, one must establish technical credibility. The TPH equity research team is staffed with engineers that have worked at Shell, Tenneco, Arco, Exxon Mobil, reservoir consultant Holditch & Associates and reserve auditor Netherland & Sewell. Dave Pursell has taught petroleum engineering courses at Texas A&M. Not only do our guys know words like non-linear flow and pseudo-steady-state..they actually understand what they mean. We’ve done decline curve work for 10-20 years. Our A&D team on the ibanking side has another group of engineering talent just like us – and they make technical assessments of reserves for a living. We know how to do this type of work.

Depth of analysis on this topic. Within the past six months, we’ve looked at 32 subsegments of US production, including individual analyses of various historical shale results (Barnett, Fayetteville, etc). The culmination of the analysis was our US Natural Gas Supply Study. We’ve got data coming out of our ears…we haven’t published it all (and won’t), but it confirms the technical work being done by literally hundreds of industry folks.

10 Reasons Why Skeptics Are Wrong:

1. Technical stuff matters – The skeptics claim Estimated Ultimate Recovery (EUR) in shales is much lower than stated by industry, analysts and reserve engineers. This is because their decline method is technically flawed and is biased to under-estimate recovery. They suggest that it is appropriate to assume Barnett Shale wells exhibit exponential decline after one year (and not apparent hyperbolic behavior). Reality – it takes many years for a very tight (low permeability) gas reservoirs to exhibit exponential decline behavior. Thus, hyperbolic decline can and should be used to approximate/extrapolate EUR’s. Whew – got through that explanation without a mind numbing discourse of transient vs. pseudo-steady-state flow.

2. Type Curves work – Skeptics further suggest that it is inappropriate to use type curves because it makes the data look smoother than it really is…and suggest that all wells should be analyzed individually. This is wrong for multiple reasons: (1) It is accurate/widely accepted to use normalized curves as long as there is a relatively stable well count and vintage/area effects are accounted for. (2) Projecting individual wells without checking the type curve trends will lead to overly pessimistic projections (see Reason #4). Type curves actually normalize for a negative bias that might be driven by individual well declines. (3) Reserve auditors project EUR’s on a by-well base…supplemented with type curves. Their by-well analysis is consistent with the type curve methods reported by companies. The answer is generally the same either way if the work is done correctly!

3. High Terminal Decline Rate is wrong – Skeptics state that terminal declines will be high in shale plays (>15%). Without 10-20 years of Barnett history (the oldest shale play), this cannot be disproved. However, there are literally thousands of data points (actual well production) that show low terminal decline rates in tight gas reservoirs. Read the technical papers. Look at the data. Enough said.

4. Reality bites - We loaded the skeptics Barnett ~1bcf EUR type curve (which are called optimistic) into our Barnett Shale model. We applied their type curve to the ~3,000 wells drilled in 2008. During 2008, actual Barnett production grew by 1.2bcf.day. The skeptics “optimistic” EUR curve estimated growth of only 0.7bcf.day – which says it underpredicted actual incremental production by 0.5bcf/day or 70%. This is only for one year. If we went back to 2005/2006 and applied the type curve to all Barnett wells drilled, there is NO WAY this low type curve would match actual Barnett production of 5bcf/d. Scoreboard!

Berman also quoted some comments by Chesapeake Energy:

"We do feel like we have the No. 1 resource base in the nation,” said Steve Dixon, Chesapeake’s chief operating officer.

Dixon said Chesapeake’s shale holdings will continue producing for years to come, despite "misguided” predictions from an analyst at an industry conference in Denver earlier this week.

"We’re very confident that these types of rocks will continue to bleed gas for decades and decades,” he said.

Jeff Fisher, the company’s senior vice president of production, said the unique size of Chesapeake’s assets will allow the company to develop new technology to maximize production.

"We’ve achieved great results to date, and we’re just getting started,” Fisher said.

I found an analysis of Berman's approach by Drilling Info Inc., Energy Strategy Partners, which seems to be better. One of their big concerns is that Berman takes results from the earliest period, and projects them forward. Natural gas companies refine their techniques over time, but this is not really reflected in the analysis.

This post also suggests that the initial wells drilled likely included more marginal producers. These are less likely to continue:

MARGINAL PRODUCER- Unlike conventional reservoirs, the economics of shale plays highly favor operators that invest in engineering and ongoing experimentation in optimizing their drilling, completion, and stimulation practices. The saying “One Man’s Gold is another Man’s Garbage” is especially true for these plays. For an equivalent grade of acreage, the best operators statistically produce 40% or more than the average operator, and up to 4 or 5 times more than an inefficient operator. Learning curves and operator comparisons are real and quantifiable throughout. As acreage expires, and the “land rush” acreages are released, the optimal operators will successfully step into “another man’s garbage”.

THE VOLUMES OF COMMERCIALLY RECOVERABLE RESERVES ARE GREATLY OVERESTIMATED - This is a very definitive statement for which the jury is still out. Mr. Berman is absolutely correct at current drilling and completion costs combined with $2.50 MCFG wellhead price. However, resource turns into undeveloped reserves fairly quickly as wellhead product price goes up or costs come down. Reducing the cost of drilling and completing a well by 50% is the economic equivalent of doubling the lifetime wellhead price. It helps to think of breakthroughs in reducing drill, complete, and stimulation costs as “permanent hedges”. One cannot address any play on wellhead cost alone. We know that there is a 80 to 100 x differential in play reserves between static D,C,&S costs and $7/MCFG at the wellhead and $2.50/MCFG at the wellhead.

HYPERBOLIC PREDICTIONS OVERESTIMATE RESERVES - Mr. Berman is absolutely correct here. This is also usually the case for conventional reserves. Hyperbolic predictions typically provide a ceiling estimate.

CONCLUSIONS - As we discovered when we began analyzing the Barnett, analyzing shale plays is like peeling onions. Once a layer is exposed, another presents itself. Many factors need to be normalized to really address the economics and behaviors of these plays in a predictive sense. Good acreage grade alone is not a recipe for success. Decent acreage grade needs to be combined with strong, holistic drilling, completion, and stimulation practices that are constantly tested for optimization to create a real repeatable recipe for success and large economic reserve accumulation. Great operations equate to better recoverable resources/reserves for these plays, not more operators or even more wells.

Raw data combines good operations with bad, early parts of the learning curve results with later, and good acreage with bad. Making forward-looking predictions of behavior from this soup assumes that every bad habit is propagated forward, and that no operator is better than another. Expanding that conclusion to other plays based on this assumption misses the big picture. What the Barnett is capable of producing is different from what it is producing now. How it can be optimized can only be determined by identifying who is optimizing it and by how much.

Conclusions

To me, the jury is still out on whether Berman's answer is right. I think the review pointing out that there are likely gains in efficiency between the earliest wells drilled and later wells drilled likely has a point. But this may be mostly reflected in the cost per well, which is being reflected in costs that are easily measurable, and not in the long-term decline curve. It is difficult to know what the impact of large amounts of fracing will be on future production.

The TPH review mentions that long term production of tight gas (such as what I observed at Wamsutter, Wyoming). But this is not really comparable--it is a different rock structure, and did not receive anywhere near the level of fracking that shale gas resources have. Also, as the reviewer from Drilling Info says, the hyperbolic decline estimates provide "ceiling estimates". So at least that part of the estimate is likely overstated, no matter how much technology improves.

I think it is likely that Berman is fairly close to right, but it would be good to have confirmation from others looking at the question in different ways. Hopefully, with greater diligence by auditors, there will be some convergence with company indications in the not too distant future.

Natural gas is one substance where there really does seems to be a lot of resource available, if the price is high enough. But for the price to be high enough, there needs to be a huge amount of debt based financing available, for all of the players involved: the natural gas companies obtaining the land and doing the drilling; the companies building pipelines and storage; and the companies building infrastructure for end use (adapting busses and cars to natural gas use; building fueling stations; installing natural gas home heating where oil was previously used). It may turn out that inability to obtain debt financing will be a big obstacle to development.

Natural gas policy is one where one really would like to have good information on how much resource is available at what price. One also needs to know what costs would be involved in new infrastructure development, and how many years these need to be amortized over to make the infrastructure worthwhile. There are other issues too--what should we really be using this resource for--chemical uses, fertilizer, commercial vehicle fuel, private passenger auto fuel? Or should we be saving it for use for balancing electrical power, when the wind is not blowing. At this point, I don't think we really know enough to make good decisions.

If cap and trade legislation is passed, it will encourage use of natural gas over coal for electricity generation. This is yet another possible use for natural gas. But the amount of natural gas we have is likely to not go very far, if this is the use chosen for it. If this use is chosen for natural gas, the amount available for use in other areas (including long-term wind balancing) is likely to be greatly reduced. So this decision needs to be considered with other alternatives, and with total natural gas resource availability.

Thanks for the summary, Gail, and pulling together those other sources.

The size of the resource even at a higher price is what's most interesting to me. If we can keep credit flowing (a big if, and I have big doubts about that, I think investment horizons are shrinking but perhaps energy might become favored), we may have an easier time on the other side of the oil depletion curve.

I'm also concerned that the fracking will harm our water supplies.

For convenience, here is a link to the ProPublica article on fracking and water:

http://www.propublica.org/feature/new-york-drilling-study-a-big-step-for...

And here is a link to a partial list (only 260 of them) of chemicals in the fracking fluid:

ftp://ftp.dec.state.ny.us/dmn/download/OGdSGEISFull.pdf

I understand the pressure to obtain that energy will be immense. However, it's not a very good tradeoff if we get all that natural gas and in exchange we lose clean water, in my view.

Edit: From ProPublica's article:

"In New Mexico, oil and gas drilling using waste pits comparable to those planned for New York has caused toxic chemicals to leach into the water table at more than 800 sites. Colorado has reported more than 300 spills affecting its ground water. And in Wyoming, an Environmental Protection Agency report found the cancer-causing compound Benzene in more than a third of the groundwater samples it tested from one of the state's largest gas fields."

Very interesting that an executive finds it neccesary to publicly state that because of one man's opinion he finds it neccesary to give up his FREE subscription. Obviously he was trying to make a change, otherwise he'd simply stop reading the publication.

If Berman were completely off his rocker he would just be ignored. He is not ignored, but hung out to dry. Perhaps he has some points in his analysis which are a bit too close for comfort.

Rgds

WeekendPeak

you have covered most of the issues wrt well economics. however, imo, what is not addressed is the bigger picture of how many wells can be drilled in any of these plays and what will the eur be ?

chk recently posted the following well spacing assumptions:

haynesville 80 ac

marcelius 80 ac

barnett 60 ac

fayetteville 80 ac

nearly all public traded companies seem to be using similar assumptions.

for the haynesville at least, many of these wells are probably economical even at todays prices (on 640 acre spacing). the haynesville is drilled on 640 and 320 acre spacing. so what happens if there are 7 or 6 more wells are drilled in each section ?

available performance data indicates that 320 ac spacing universally results in reduced eur/well on 320's vs 640's. the jury is still out as to whether 320 ac wells can be drilled economically.

so, imo, multiplying 6.5 bcf/well times 8 wells per section is insane. this is where the 100 yr supply fantacy comes from.

berman's data showing receeding eurs vs time for the barnett could indicate that wells are being drilled too close together.

Spacing was not an issue I tried to look at.

I know when I visited Wamsutter, they were looking into closer spacing, but the conclusion seemed to be that in order to be economic, it had to be restricted to areas with the greatest resource density. It seems like the situation with shale gas would be similar. The amount that can done will really depend on the cost of extraction--unless one can get adequate recovery per well compared to the cost of extraction with the selected spacing, it doesn't make sense to drill wells closer together. If Berman is right about the long term recovery being less than expected, this result would argue against close spacing.

yes, i believe wamsutter is technically called a tight gas reservoir which is similar to but not the same animal as the shale gas reservoirs. i am not that familiar with wamsutter, but the jonah field consists of a whole column of sand and silt lenses and the lenses are small in areal extent. these are being drilled, apparently successfully, on 10 ac spacing. that is probably the only way to access these small lenses.

I thought the comment about Wamsutter not being fracked like the shale plays was interesting. In the Pinedale Tight Gas play they are running about 8-12 fracks per well and I have seen as high as 18. Overall though, the shale and tight gas plays are different animals. The decline curves and cumulative recoveries in Pinedale have been very good.

My comment is based on the impression that they weren't doing all that much fracking back years ago. So it is hard to infer tail declines now, based on the patterns of wells that had had less fracking in the beginning.

I wonder to what extent fracking really increases the total amount available, and to what extent it moves it forward in production? It seems like if it really works well, it could result in less being recoverable during the tail period.

I think you meant "total amount recoverable" and not "total amount available" as the amount available is essentially the capacity and is what it is. Not criticizing, just pointing it out.

However, the amount recoverable during the tail period, which might be defined as Y2 thru P&A, is THE CRUX of the entire debate and no one wants to talk about this. As Rockman says, URR means nothing in the decision to drill and that is absolutely true. But, URR means something in terms of U.S. Energy Policy. If these operators are running us down a dead end street, then I think they should be called out like what Berman is doing.

IMO, Nat Gas could be a top priority of U.S. Energy Policy and the shale plays are the linchpin. If we are getting bogus estimates of the potential, then that is a problem......a big problem.

McClendon, Nichols, Wilson and the other E&P CEO's cheerleading the shale plays have a duty to provide accurate estimates. The rebuttals to Berman's analysis, save for Drilling Info, have been a joke, especially TPH. Now is the time to quit grandstanding and be honest. Debate the issue and at least come close to agreeing on the results. I really want the E&P's estimates to be right, but..........

This is not a rant directed at Gail or anyone. It is a question that needs to be analyzed with great care and answered very soon. If not, then U.S. Energy Policy could turn down a road of promoting energy sources that have not been proved economically. Unfortunately, we might already be there

You said it better than I did. It is hard to get people excited about a technical issue, but it makes a difference for our natural gas strategy how much natural gas is really recoverable at a price the economy can afford. The amount of infrastructure needed for a big gas ramp-up is huge. There is no point on working on a big natural gas ramp-up, unless the gas is really there.

"McClendon, Nichols, Wilson and the other E&P CEO's cheerleading the shale plays"

Well, isn't that usually the job of a CEO trying to gain investors? It's just like most of the Renewable technologies that are going to save the world. Only "erring" in over-exuberence by 100% is within bounds.

It makes a good story...

Here's a biased and very opinionated view of the subject matter. I've done the type of analysis under discussion for over 34 years. Doesn't make me an expert but I do know exactly how the process works.

First, the ultimate recovery debate is a straw man. I can tell you emphatically that URR is of little importance in drill decisions for every operator. In the basic economic models that number shows up as a cum at the bottom of the yearly production column. And almost no one even looks at it. Economic analysis of an oil/NG investment is extremely time sensitive. It doesn't matter if the URR is 10 bcf if it takes you 40 years to recover it. The cash flow is discounted...typically by a 10 to 15% rate. If you do the math you'll discover that the revenue stream beyond 7 or 8 years makes very little contribution to the Net Present Value of the project. And NPV is one of the key factors in the decision process...not URR. There are SG wells that have been producing for over 50 years. Even at 40 mcf per day (less than $100 net at today's prices) that would add up to 3/4 of a bcf = almost $3 million. But in a NPV calculation that $3 million would be reduced to almost nothing and thus add a relatively small to the value of the project as they are judged by industry standards. And NPV is one of the key metrics in evaluating a publicly traded company...and not URR. But throwing out big URR by a public company is a good way to hype unsophisticated investors.

I'll offer an easy way to look at this numbers game: You loan me $100 and I agree to pay you back $500. A good deal for you? Depends: if I pay you back $0.25 per week then it takes about 40 years to get your $500. Wanna loan me $100?

The second, the type curve argument is BS. These are pressure depletion reservoirs. They are the easiest to estimate URR on a PER WELL BASIS. Mother Nature has kind to reservoir engineers in this regard. Simply plot the flow rate on a log-normal scale and it's very easy to project AFTER you pass through the initial high decline rate period. Granted, the model during the first 2 or 3 years is subject to interpretation. Type curves is one way to make an estimate. But you do that on an individual well basis. Regardless of what the industry talking heads might seem to be implying they have all done this on their individual wells. That's what they pay their engineers for. If they toss out regional or area projections based on clumping X number of wells and then applying type curves they have a very good reason IMO: it because it offers a bigger URR then what they've calculated doing the wells individually and then adding the numbers. I've done this trick more times than I can remember in an effort to blow smoke up some banker's butt.

Terminal decline rates: same deal as described above with Net Present Value.

As far as what the skeptics are offering I don't know if they are being too pessimistic. If they are taking a minimalistic approach that's fine but that also makes them more vunerable to arguments from the SG players. Currently I understand my former client, one of the big SG players, is ramping back up. I suspect this is due to the big drop in drilling/completion costs. Even before the NG price collapse last year the margin on SG wells was getting slim due to the ever escalating rise in costs. This feed back loop will continue IMO. More SG ops and costs begin to rise again. If NG prices don't improve the increased cap costs will surpress additional drilling efforts. You're basic chicken and egg scenerio.

I suspect that Berman is primarily doing the latter exercise, the optimists the former. But in any case, this is why I asked if there were data available for Bakken Shale wells on leases where no new wells were being added. And it seems to me that this is the also way to make some progress in the SG debate. Why don't we look at the production performance from leases where no new wells are being added?

Also, isn't one contributor to rapid exponential declines the tendency for the fractures to close as reservoir pressure drops?

WT -- From what little details I understand about the Barnett it's the fracture close factor which has led to refracs efforts. Not sure how common refarcs are but if significant it should only cloud the discussion.

I guess we are back to the same issue--let's look at some leases where new wells are not being added.

In any case, I wonder about the sheer scale of the effort needed to keep steadily increasing the annual number of wells drilled and completed, even if prices were high enough.

yes, permeability is lost from the natural fractures and micro-fractures when pressure depletes. these fractures were apparently induced when the volume change in the conversion from kerogen to hydrocarbons caused a pressure increase which induced these micro-fractures. keep in mind that this is ultra low permeability (matrix) rock. initial reservoir pressure in the thermally mature area is at a normal frac gradient (~ 0.7 psi/ft depth)

dan stright, etal did a study(spe 24320) of these hz bakken wells way back when hydraulic fractures werent in the picture.

refrac's apparently do have a benifitial effect, at least temporarily, but the economics are far from proven.

you asked about decline from leases/fields where drilling has stopped and i will find you a good example. it will take some time.

yes, i would loan you $100. $0.25/week is a lot better return than from my fat lazy brother-in-law.

I know what you mean elwood...I have a couple too. But I also have a policy: I don't loan money to folks who still owe me money. A couple of loans to my brothers more then 20 years ago and they haven't asked again. A good investment a I see it.

BTW --You can use Paypal to send me that $100...thanks

I thought you wanted a quarter. ;) It'll be a really shiny quarter, too.

Thanks for your insights.

Without seeing what is really going on from a company's perspective, it is hard to interpret what is happening. I do not really know enough about what is going on to understand the situation, but it seems to me that long term loans likely play a big role in these calculations. These long term loans are at least in part available because of the high ultimate recovery estimates that are being put forth, so there seems to be some connection between what Berman is saying and NPV calculations.

I think the last point you made is a key one. Natural gas is dominated by a huge number of small players. They all tend to be on the optimistic side. So they will all drill wells when the economics aren't quite "there," because they think this well will be better, or technology is improving, or because their investors expect them to and the money is available. The result is likely to be a lot of barely profitable companies, and many that are out-and-out losing money. This is not a formula for long term success.

I would feel more confident of the long-term availability of natural gas if there some agency looking out for the American public in charge of setting prices and mandating maximum production. This is not likely to happen, without government take-over of the industry (and maybe not even then.)

Gail -- Sort of a sweet and sour proposition for the bankers. Once the wells hit the low decline rate you can't find a more secure borrowing base in the oil patch (ignoring price fluctuations of course). OTOH, so much of the cash flow/NPV is predicated on the first couple of years production the bankers get nervous. But a large solid base of older production gives them courage which can be misinterpreted as their lending credence to the hype.

"some agency looking out for the American public": scary thought gal. Kinda like asking the mountain lion to protect the sheep from the wolves.

These shale gas wells produce for about 4 years according to the USGS. An average Marcellus well will produce 2.5 Gcfe over that short time NPV is not an issue at all.

At the breakeven point,

Fixed cost of well/(Sale price of gas - Variable cost)= EUR

So if the price of gas is $3 per mcf and the variable cost is $1(USGS) per mcfh and the well costs $3 million then the EUR needs to be

>1.5 bcf; $3000000/($3-$1) per thousand = 1.5 Gcf.

Berman is very pessimistic on costs as he says $7 per mcf is needed to get to even a 1.5 bcf breakeven or fixed costs would be

($7-$1)*1.5 Gcf/mcf = $9 million fixed cost(well).

On useful life of a well, Berman is all over the place from 2 years to 56 years from maximum to 1%. If Berman is right shale gas will fade away in 2-4 years when operators go broke otherwise shale gas is real.

Right now shale gas is getting big in Europe where prices are much higher--so I would guess that Berman is wrong.

http://aspo-usa.com/2009proceedings/Art_Berman_12_October_2009.pdf

http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2009/3032/pdf/FS2009-3032.pdf

maj -- NPV is always an issue. I meant what I said although it may sound odd: URR, by and large, is not a determining factor in any company's drilling considerations. For most comapnies if the NPV doesn't exceed the total well cost they don't drill. Also, I not necessarily supporting Berman's position. I'm just explaining how the process works.

A lot of "ifs' in your analysis. The last time I saw cost numbers a SG well would run between $4 million and $9 million. Depends on the trend and the completion design. There is no such thing as an average or typical cost...too many variables.

On your "Fixed cost of well/(Sale price of gas - Variable cost)= EUR" you've lost me. Are you implying how much NG a well will produced can be predicted by your formula? And with respect to "These shale gas wells produce for about 4 years according to the USGS" I'll assume you're misstating. The great majority of SG wells will produce commercially for decades. As I said earlier, there are New Albany SG wells still producing commercially today after 40+ years.

As far as SG fading away in a few years that's certainly wrong. The SG play has already faded away to a fair degree. Check the rig count. I mentioned before my former client dropped 14 of the 18 drilling rigs it had working in the Texas SG plays earlier this year. And paid a $40 million penalty to do so. That has to tell you something about what the players in the trend (the folks who know all the real numbers) think about the current economics of the SG play. I do think we might see an uptick in activity in the next few months. I suspect the main reason is the drop in drilling/completion costs. There are sweet spots in every trend that outperform the average. With lower cost these sweet spot can become attractive even at low NG prices.

Again, I'm not saying Bergman is correct. But I understand very clearly where the press releases from the operators are coming from and their motivation.

Does anyone have shale gas drilling rig count comparisons recently? I know I saw some earlier this year, and that natural gas rigs in total are in decline a lot. A big decline in drilling rigs suggests things aren't all that rosy.

Gail -- It's difficult to sort out without researching individual drilling permits. Some reports offer "vertical" rig count vs. "horizontal" rig count. Worthless...there are no horizontal rigs...just rigs that can drill horizontal wells which can also drill vertical wells. Even a drilling permit search doesn't help. In Texas you can get a permit to drill a horizontal well even if you don't check "horizontal" on the permit application. If you search "horizontal permits" in the data base you'll see far fewer then there actually are. Gas well permits are an easier search but it doesn't distinguish between vert and hz.

But the gas well permit count has been rising. But were still less then half (760) the max of 9/08 (1600). There does appear to be an increase in TX SG drilling in the wings from some inside reports I've gotten. Instead of 1 of the dropped rigs coming back from the 14 rigs this operator dropped earlier this year they are planning on 4 in the next few months. As I guessed elsewhere this might be driven by lower costs. But a significant surge in drilling might start running the costs back up in time.

There's NPV and then there's Break-even.

They are totally separate.

NPV is used to choose between investments, break-even is if you can cover your costs. If your costs are higher than your revenue your just plain out of business.

Most everyone in business knows about break-even.

(Are you putting me on?)

Total fixed cost/(Sales-variable cost)= minimum EUR/URR.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Break-even

My point is that the shale gas resource though perhaps not as huge as Chesapeake is saying is still large enough to supply the US with gas for +70 years(1400 TCF, mainly unconventional) rather than 20 years of conventional gas(390 TCF). After a few years shale gas wells will be stripper wells.

As long as the wells pay for themselves with a small profit, they'll be dug and gas prices will rise sooner or later.

maj -- We don't call it "break even". We call it "pay out" but same thing. That metric is given in years. A 24 month PO indicates the time it takes to recover capex costs and operating expenses from the net revenue stream. PO is considered almost as important as NPV and is obviously related. No...they are not totally separate: can't have a well with an attractive NPV and a 5 year PO. As a general rule most operators start losing interest in a drilling project when PO exceeds 2 years. Today most prudent operators want at least a 4+ to 1 ratio of NPV to capex.

As Chesapeake say, SG could supply us 70+ years. Or for 10 years. As I keep saying, it depends on your price assumption. And I can equally say conventional NG will supply us for 70+ years...if the price is high enough. There is a huge volume of proven and technically recoverable NG reserves in the gas shales. How much will be recovered is completely dependent upon the price of NG.

But you are exactly right: after a SG well reaches PO it can continue producing commercially for decades even at relatively low NG prices. Stripper SG wells are about as cheap a production operation there is. As I said earlier, there are 40+ year old SG wells still producing today profitably even at the current low price. But again, whether you choose to believe or understand it, the industry does not assign value to those late produced volumes. If I were buying a stripper SG field today I would contribute almost no value to reserves produced beyond the first 10 years even if it's proven the wells will last 40 years and produce twice as much NG in the last 30 years as it will in the first 10 years. More importantly, the seller wouldn't expect any value pricing for those reserves either. But that doesn't change the fact: very few SG wells will be drilled by Chesapeake or anyone else if the projects don't meet fairly standard PO and NPV metrics. Many of the wells drilled during the SG boom last year barely met these criteria. That's why the operators ran like scalded dogs when prices collapsed. Chesapeake et al can blow all the smoke they want but their actions when the price fell tells you exactly what they truly think about SG: there's very little reserve potential at those prices compared to the in place volume. They all but stopped drilling for a very good reason. But public companies have an addition metric they must meet to satisfy the stock market: reserve replacement. I've told the story before: I've drilled wells for public companies even when the company didn't expect to make a profit from the project. In other words, no PO and a NPV less than the capex. An absolute money losing proposition anyway you measure it. And regardless they insisted I drill the wells because they had to meet the market expectations or their stock options would be worthless. As was once said, watching sausage being made can ruin your appetite for it. Same thing in the oil patch: you just hold your nose, do the job and submit your invoice.

I don't think we're really looking at matters that differently. I'm just saying that when Chesapeake or anyone else says there are X TCF of SG that can be produced but don't offer a price assumption to go along with that they number they are lying scumbags. Lying by omission is still a lie in my book. Especially when you know exactly how that omission will lead folks astray in their thinking.

The fact rig count dropped so dramatically makes it clear that producers really don't think $4 natural gas is profitable--regardless of what testimony to congress said.

One thing about the long lifetime--which may not be important to investors, but which makes a difference to people who think they will be using the natural gas--is the dependency of this natural gas production on oil availability. Out in Wamsutter WY, the dependency on the oil infrastructure was very clear--all the servicing is done in trucks powered with oil; the facility is in a remote area, so all food has to be trucked from great distances; workers who live nearby have to drive 80 miles to get to the closest physician or Walmart.

It may not be as bad with the some of the shale gas, but the issue is still there. Perhaps vehicles powered with natural gas can be used to get around from plant to plant. But there will still be a need to keep the roads in some sort of passable condition. And heavy equipment that comes in for refracking and the like will likely require diesel fuel. Liebig's Law of the minimum will determine when production stops. Even if "most" functions can be handled without oil, when some critical function cannot be, the operation must cease.

Can these low volume NG wells be operated by individuals, like the oil stripper wells? Don't know why not, but thought I'd ask, and see if there are any caveats.

KLR -- Sure. In fact the vast majority of stripper oil and NG wells are operated by individuals. Big companies just can't justify the overhead associated with such low revenue operations. SG wells are even easier to operate then oil strippers. These wells flow very low volumes of NG at very low pressures. In fact, it's not to different to residential NG distribution. As long as the equipment doesn't break down all the operator does is cash his check ever month from the buyer. The biggest aspect of operating can be compressing the NG. It's produced at such a low pressure the operator has to raise the pressure to get it to flow into a sales pipeline. This equipment is expensive and not so easy to maintain. But typically the compressors are NG fueled and thus use part of the production stream to operate. This is free fuel and THE only reason most of these wells produce for so long. They might burn half the produced NG to run the compressors. But it's free. The compressors are often used on a rental basis. Thus as long as there's enough cash flow to pay the rental and maintenance you just keep producing and cashing those check.

I can promise you that when the current SG wells get down to stripper rates they will be sold off by the big players today. A large company does not function well at those low volumes. Too much over head. They'll be sold to small and very small companies where the income will go directly into someone's personal checking account.

ROCK you have shed a lot of light on stripper wells here through the months. You might recall I have a bit of an AK angle on 'one or two' of my posts, which brings me to my question. Will remote giants like those on the north slope have any way to still produce profitably when they get to the 'stripper stage?' I'm talking oil wells here now but someday the gas will be produced as well. No doubt BP, Conoco and Exxon (biggest gas lease holder) will need big volumes but do you see anyway that stuff could still get to market after the big boys lose interest?

Would owners of stripper SG wells have to live physically close by? Don't these well need to be checked on fairly often (either by radio signals or directly)? Would a company typically own a few dozen (or a few hundred) wells, or what?

do you have a reference?

that is not at all what public traded companies are saying, in fact 50 - 65 yr life is often cited and older(vertical) marcellus wells are pointed to as an example.

exxon mobil and falcon oil and gas recently plugged their shale gas test in hungary.

Arthur Berman reference--Berman say 4.5 years with 'hyperbolic declines'(exponential I think).

http://aspo-usa.com/2009proceedings/Art_Berman_12_October_2009.pdf

USGS references an average producer well pumping out 4 mmcf per day or 1.4 Gcf/a which I take to be over the first year with an EUR of 2.5 Gb. I forgot where I saw 4 yrs with USGS.

http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2009/3032/pdf/FS2009-3032.pdf

At any rate the URR of US shale gas is very large and so at the right price it will be available.

Estimate is 510 TCF of gas from shales in Western Europe.

http://www.searchanddiscovery.com/abstracts/html/2009/annual/abstracts/s...

According to may reading of the Berman ASPO presentation, he is talking about an average well life of 8 years. He says "4.5 years to abandonment". I take that to mean that the wells we has looking at were 3.5 years old, so on average, they had 4.5 years to abandonment.

Gail -- Perhaps Berman is being sloppy in his context. SG wells, for the great part, will produce for decades before abandonment. As I've said elsewhere, there are many still producing today after 40+ years. Maybe he's trying to say they'll produce a relatively insignificant volume after X number of years. But if means exactly what's written then he's lost all credibility and proves he has virtually no understanding of NG production.

Here is is reasoning regarding the Barnett Shale. It is interesting that 15% of the wells in their control group have already reached their economic limit, five to six years into their production life cycle.

http://www.aspousa.org/index.php/2009/08/lessons-from-the-barnett-shale-...

Berman: Lessons from the Barnett Shale suggest caution in other shale plays

Clearly the cutoff depends on the netback gas price.

As I mention above, I think oil availability long term is likely a limiting factor in long term production. While most functions can at least theoretically be handled with natural gas (natural gas powered servicing trucks, for example), Liebig's Law of the Minimum holds. If some critical function cannot be handled (for example, worker's getting to work; roads being kept in passable condition; maintenance on pipelines), the whole system is likely to grind to a halt.

Gail -- What is "netback gas price"? Not familiar with that term.

I'm assuming that Arthur means the net price at the wellhead.

http://www.investopedia.com/terms/n/netback.asp

those whacky canadians use that term a lot.

Note the cutoff volume he is using is only 70 MCFPD.

Rockman,

Perhaps you should write our articles! You have clearly made the most important points that arise from the work that Lynn Pittinger and I have done. Thank you.

When asked by people why there is such a disparity between our conclusions and those of critics, I say:

1. Reserve estimates based on type curves or models of any sort will always be wrong.

2. Hyperbolic models will over-estimate shale gas reserves based on production history in the Barnett and Fayetteville shale plays.

3. Hyperbolic models have not been demonstrated to apply to the current shale plays. These models derive from fractured Appalachian basin shales with 1000 times more permeability than the Barnett, etc. They are further based as you say on "tight" sandstone reservoirs that are also not comparable. In a recent Simmons & Company report (I doubt that Matt had anything to do with this propaganda since it contradicts most of what he has said publicly about shale gas), it is revealed that hyperbolic advocates even invoke over-pressured limestones in the Anadarko basin as analogues!

4. None of this really matters because, as you point out, there is very little present value after 5-10 years, depending on initial rates and decline rates.

5. Costs are not stated accurately by operators and many financial analysts. I have studied the 10-K and 10-Q SEC filings of all of the major shale players. According to their stated costs, an Mcf of gas costs about $7-8 on average to find and produce for most companies. Whenever, someone says that profits can be made at sub-$5/Mcf gas, I ask, "What costs are you not including?"

6. The other sleight-of-hand on costs is to inflate the reserves claimed. The bigger the denominator, the smaller the $/Mcf appears. If we are anywhere close to correct about reserves, true costs could be 100% higher or more.

7. Back to decline rates, almost everyone on the other side of this debate has re-invented the rules of decline-curve analysis as defined by a body of peer-reviewed SPE papers. They incorrectly model the steep initial "transient-transitional flow regime" resulting in preposterously flat decline rates. When I mentioned this recently to an exceptionally reasonable and sane employee of a reserve auditor, he said they account for that by imposing a terminal decline. Now we have to argue about how to determine terminal decline, and shale proponents will go back to the examples cited above that are not comparable to find an absurdly low rate. Why not just do it right to begin with? Why would you use any part of the decline history that does not best predict future decline rates?

As a footnote, I want to express my appreciation of and respect for the informed and penetrating posts that I find on The Oil Drum. I had a nice note from Nate Hagen today saying that since leaving World Oil, The Oil Drum would be pleased to host our articles. Thanks to all!

wrt the haynesville, my take on it is that they are basing their reserves on volumetric calculations and force fitting the reserves to shaky to begin with calculations and applying a completely arbiterary recovery factor to arrive at this eur. i arrived at this conclusion from studying the various prs and presentations of chk.

p.s., i still think you should take a look at an analysis based upon rate -vs- cummulative.

Thanks Berman but I'd rather take my shots from the cheap seats. I'm not completely hostile to the hype put out by Petrohawk et al. I've had to shine up more than one pig in my career. Blowing smoke up the stock market's butt is an honorable position IMO. As they say: let the buyer beware. But what troubles me is when the hype filters out to the general public and they use this information to influence the political system. I've got nothing against screwing with a market analysist...been my job more then once. But screwing with the public and their perceptions about PO is a whole different matter. That can lead, at best, to a slow reaction to reality. At worse, it can lead to more body bags coming through Dover. And that is very unacceptable to me.

Our problem is that there are too many who are willing to believe hype without questioning it. One would think that the government would want a "straight" set of facts, but especially on the oil side of things, they have been the worst to put out propaganda about lots of oil being available in the future. Newspapers for the most part don't question what they are told. They like to put out a "happy story", whether or not it is true.

Wow.

This is why I love the "Oil Drum".

This kind of discussion and analysis is unavailable anywhere else.

The other week, Jim Cramer (CNBC) was extolling the wonderful future of the unconventional natural gas plays; how they will solve all our energy problems, etc... IIRC he had a guest gas company CEO on to help him out with the pep talk. I'm sure a good number of people have piled their money into these investments. (I have nothing against Jim Cramer. He seems to be a sincere guy and I suspect he has even helped people to make some money here and there. But Jim! You claim to be a "fundamentalist" when it comes to investing. Let's do some real research on the fundamentals of energy production for a change!)

Cramer is always a good barometer...of where NOT to invest. Hard to believe that anyone would keep him on the air.

CNBC has to keep promoting cheerleaders for the economy. They already chased off Dylan Ratigan, who was the lone voice of reason on that whole channel, to MSNBC...

My one Cramer story. In 2003 I was sitting in my brokers office discussing investments when Cramer came on the little office TV with a fist pounding rant about McDonalds stock, which had just dropped all the way to $18. He was basically shouting that all of you who think it is now a good buy are out of your mind because the MacDonald business model was broken and it would continue to tank. Since Cramer always struck me as an idiot I promptly told my broker to buy 300 shares. My broker was shocked and said "Didn't you hear what he just said?". So I told him that Cramer is such a blowhard and usually wrong I want 300 shares now. So he registered the trade. Frankly I had paid no attention to MacDonalds so it was just an emotional reaction. I think it went down another dollar to $17 the next day but I sold it 6 months later for $29. Probably should have kept it.

I also dropped my broker right after that.

i think you captured the essence of cramer.....claims to be a fundamentalist and tries to catch the latest wave.

we have seen recently that it is difficult for the price of oil to go much over $80 without it causing a recession. Natural gas is a smaller part of the economy, but I suspect it still has issues with too high a price being recessionary.

NG is very different from oil: we only import 15% of NG.

It's the outflow of money for oil imports (and Asian goods) that hurts the US economy.

That's far too broad a statement. A high oil price also makes a difference even if the oil were bought domestically — that money doesn't go into other productive uses, like wages, for instance.

that money doesn't go into other productive uses, like wages, for instance.

Sure it does. We're talking about wages for all the people doing the drilling.

The important thing is the money stay circulating in the US. That's what causes oil-shock recessions - the money leaving the US. That's why the US weathered the first several years of oil-prices just fine: petrodollars were being recycled. Then the RE bubble burst, CDO collateral evaporated, and petrodollars stopped recycling. That's also why T-bills (sovereign borrowing) are being substituted for toxic CDO's.

Now, the human value of the activities that make up GDP - that's another question. But, GDP will be relatively unaffected by higher NG prices.

The three of you are all quite off. First, you buy oil because you feel it is most beneficial to you, otherwise you'd use the money for something else. Second, the money paid IS used for "wages", i.e. for buying American goods which you need labour to produce. (If it isn't used for this, you guys got the oil for free and could just print some more money to adjust for any money-supply shortfall!) Third, money should not circulate in the US only - that's mercantilist nonsense.

You do get poorer when import prices rise (because others can get to more of your production), but you need not get recessions, nor unemployment, because of it. And you'd get even poorer if you restricted international trade. Please do take an Economics 101.

Economics 101 is for morons. Let's assume a level playing field, let's assume no taxation of any kind, let's assume zero government corruption, let's assume a meritocracy, let's assume blah blah blah blah. Tariffs (taxes on international trade) do not magically cause poverty any more than any other type of taxation. Tariffs are bad because they can tend to shift power to workers, and like you say, power needs to stay in the club.

Then take a more advanced course, if you feel 101 is to simplified. I just noted that your knowledge of basic economics seems very limited, but I don't really know how thorough American courses are.

Tariffs do shift power from the general consumer to (a few) workers. (Just look at the Obama tariffs on low-cost tires.) "The club" however, often doesn't mind - capitalists have an easier time and may increase profits if they are protected from competition.

Tariffs do cause poverty and moreso than general taxes, because tariffs are used to curb competition, while most taxes are constructed to be more neutral.

International trade-when it is reasonably balanced and conducted under free enterprise -is a fine thing.

International trade as we have it these days with near monopoly capitalism and tremoundous inmbalances long perpetuated is a sure fire recipe for disaster.

The international corporations are playng both ends against the middle and both ends lose-except for management and stockholders.

The typical consumer may win for a while-it depends on whether his job is exported.

After awhile , the typical consumer finds himself in a squeeze from two directions-first , his own job in an industry selling to the job dispossessed may be lost or business may be slow enough that opportunities for promotion are few and far between.

Second he finds himself surrounded after a while with former workers living at his expense on food stamps , rent subsidies, and medicaid.If he does lose his job, he will be competing with many applicants when he looks for a new one, and wages will be depressed.Meanwhile crime is probably rising and the classrooms at the local schools are getting crowded.

But the folks collecting management salaries at the job exporters and selling thier stocks and raking in the big capital gains are doing just fine.

Somehow even after the system crashes , they still rake it in by the millions.

It's enough to turn you into a democrat-except for the fact that they were in on the party all along as co conspirators and enablers.Guilty-but not quite AS guilty.

What you present is ignorant and dangerously so, as the policies your thoughts may shape would make Americans and everybody else quite a bit poorer and more prone to international conflict. Much of the Great Depression and what came after was caused by such thinking. I do agree that what you write is a conspiracy theory, though, and that insight of yours should be useful to you if you ever decide to read up on this or think for a bit.

Edit:

Sorry, moved comment upstream.

Cheers, Dominic

Second, the money paid IS used for "wages", i.e. for buying American goods which you need labour to produce. (If it isn't used for this, you guys got the oil for free and could just print some more money to adjust for any money-supply shortfall!)

That's the whole point of what China, Japan and oil exporting countries have been doing for decades: they're hoarding money (in the form of T-bills), instead of buying from the US.

It's very similar to what China did in the 1800's, when they were willing to accept gold, but not buy anything from the US. That sparked an invasion of China.

A high price for a key item like oil means less money for other things I might want to buy.

It's no different than the U.S. paying 13% of its GDP for health care, sure some of the money goes to wages, but that high ratio is widely acknowledged to be a drag on the economy for good reason: where else could all that money have been deployed instead? Same thing with the money spent on wars and the military machine. I don't know about Econ 101 but this isn't rocket science I'm pointing out.

Well, the US privately funded healthcare absorbs 13% of GDP (almost all goes to wages). In Europe, states' near-monopolies on healthcare funding cuts that spending almost in half. I'm not sure why the latter would be better. Is healthcare spending really so bad that it should be rationed?

If you guys feel that some spending is excessive, why don't you consider curbing that government spending and government regulations that drives costs and consumption in the sector? For instance, why not abolish tax-deductions on employer-organized health insurance?

Can't possibly think of how 6 1/2% of the U.S. GDP could be spent better (U.S./Europe differential you give). Those wages could go into sectors that would give us a much better long term outcome (of course they could go into worse sectors or disappear entirely, but that is a whole book's worth of discussion). The U.S. system is broken. Anecdotally, I have watched many simple little couple/several hundred dollar invoices bounce back and forth between my wife's and my tripple coverage carriers for 18 months to two years repeatedly. Every time that invoice is handled (some bounce just about every month but fade to every two or three months after about a year) it costs money. The health care service providers not getting paid for up to two years means they have to add the cost of borrowing money for that length of time to their bills.

What is in the works now won't be worse than what we have, but there will be winners and losers. Whether whatever reform we get will start us toward a sustainable health care system or whether it is even possible to do that this late in the game remains to be seen.

I would suggest that the answer lies less with "spending" but more with "consumption". You pay someone to work or give you a resource. The money, on the other hand just changes hands - who cares about the name of the activity.

On the other hand, the macroeconomic question should be: Does the seller create a value through his work? What value is actually added? Or are resources being depleted?

Again, money circulation is a worth-less activity. Is the activity on the other hand creating or destroying "value"? Cheap junk from China is surely destroying value while insulating your house is (usually) creating value...

Whether this happens on an international basis or not is secondary. That's only the question to whether the money circulates in large circles or small ones...

Cheers, Dom

Hello Nick,

Your Quote: "NG is very different from oil: we only import 15% of NG."

Yep, as discussed in detail in my many earlier postings: NG is Very, VERY Different from oil when the [N]itrogen is Haber-Bosch transformed in quality and utility into I-NPKS ferts.

Have you hugged your bag of I-NPKS or O-NPK today? There are No Substitutes to these Elements to leverage photosynthesis above a Liebig Minimum, and I know we all like to eat...and O-NPK recycling certainly is not being ramped like I would wish to see it...

http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/nitrogen/mcs-2009-nitro...

--------------------

USA Net import reliance as a percentage of apparent consumption = 48%

Import Sources (2004-07): Trinidad and Tobago, 56%; Canada, 15%; Russia, 12%; Ukraine, 10%; and other, 7%.

--------------------

IMO, our national security and the very survival of local I-NPKS mfgs. depends upon a definitive answer to economic viability of SG versus Conventional NG. My guess is that nearly 100% of USA local I-NPKS plus the 48% import portion is all derived from conventional NG [not SG] as one just cannot easily plunk down a massive, multi-billion buck, multi-decade use, Haber-Bosch facility just anywhere on a whim.

Thus, from applying the Precautionary Principle: you would expect the I-fert companies to be screaming here on TOD, and/or in the Halls of Power, for a totally exhaustive data-analysis of SG long-term prospects, for subsequent comparison against conventional NG.

I would sure hate to see conventional NG peter out, thus 48% of our I-NPKS imports goes poof--imagine what food prices would be--then watch SG peter out at an even faster decline rate [if Berman is correct] so that local sources of I-NPKS ferts go poof, too.

Again, recall my Ft Knox scenario if we don't plan ahead. Strategic Reserves anyone? Damn hard to convince people of building real-asset 'Federal Reserve Banks of I-NPKS' when most are focused on the dead presidents of fiat currencies... too bad, too sad that they cannot shift their focus just a few generations ahead; "She comes down from Yellow Mountain..".

Of course, the Grim Reaper is constantly & supremely focused; he must be laughing as we Frac-away to wreck local aquifers and stream flows...

EDIT: if one understands cascading blowbacks and Fractals: the pressure release off an Amazon butterfly's wings could eventually cause a hurricane... what are the potential Fractals to globally erupt from the millions [future billions?] of underground Fracing pressure releases and top-surface chem-releases?

Bob Shaw in Phx,Az Are Humans Smarter than Yeast?

Don't worry we still have a little conventional NG up this way, 35 trillion cubic feet proven reserves just in the central Alaska North Slope region, the area we have pumped over 15 billion barrels of oil out of so far. The total technically recoverable NG in AK is more like a couple/few hundred trillion cubic feet. Look at the wage scales of the I-NPK exporters, I'd bet Florida wages are better than Trinidad/Tobaggo's. That couldn't possibly have any bearing on where the manufacturing plants are 'plopped down', it doesn't in any other industry, righttttt. But you are right, the world burns NG at a hell of a clip, better than a hundred trillion cubic feet annually worldwide. Once burnt it don't make fertilizer no more. The big picture needs to brought into focus.

Historically, quite a lot of the oil money has ended up recycled into US treasuries. The impact has tended to keep rates down, and has led to less impact on the US economy than one might expect. But long term, it is hard to see how perpetuating our balance of payments problems can end well.

People who spend more for heating and electricity because of high natural gas prices will have less to spend on discretionary goods and even mortgages. At some point, the higher payments contribute to recessionary impacts and debt defaults, just as high oil prices do.

Gail,

This has to do with money circulation. If money leaves the country and doesn't come back, US purchasing power declines. If money leaves the country and comes back in the form of debt, income & employment levels stay the same, at the cost of debt. If money leaves the country and comes back in the form of purchases/exports, income & employment levels stay the same, and our level of wealth stays the same, at the cost of consumption that leaves the country.

Of the 3 choices, the 3rd is by far the best. People don't lose their jobs, or go into debt, they just consume a little less: keep their car longer, buy fewer ipods, etc, which is far less painful.

New costs in the US, like higher drilling costs, are very similar to choice #3: some people work in the gas industry rather than in another industry - that other industry (say, cars) is a bit smaller, but that's not very painful or disruptive.

This discussion parallels the debate in Australia over huge LNG export deals. Some say Australia has 500 years of natgas and coal seam gas reserves, others say 65 years. The optimists are pushing for both gas baseload electrical plants and gas backed renewables. The big unknown is gas powered transport. My suspicion is that motorists will look at PHEVs like the GM Volt and conclude they are too pricey and the all electric range is too short. NGVs then look appealing despite the heavy tank and lack of zip. I note even the popular Toyota Camry now has an NGV prototype http://www.greencarcongress.com/2009/11/toyota-sema-20091103.html#more

I suggest that known gas reserves be allocated as follows

high priority ammonia based fertiliser, industrial process heat, domestic gas, transport

medium priority gas backup of wind and solar, gas-to-liquids, combined heat and power

low priority heating of tar sands, gas fired baseload, export via pipeline or LNG.

With adjustments for location, prescribed percentages of gas output should be set aside for the higher priority uses. It would be stupid to increase gas fired electrical generation the same time it was needed for transport. Use nukes for even lower CO2 electricity and save the NG for cars and trucks.

There's going to be enough natural gas for the emerging Plutonomy. After all, when 99% of the world's population stops mattering as "non-rich" consumers who have only minimal statistical impact on overall consumption, the remaining 1% can consume like there's an endless party.

By the way, that is Citigroup who is claiming the world is becoming a Plutonomy, not some obscure tin foil hat conspiracy nuts.

Plutonomy: n. An economy that is driven by or that disproportionately benefits wealthy people. Have fun in the Brave New World of Tomorrow, all you egalitarians. Your dreams are being eaten alive by Wall Street.

After all they have been involved with, why would anyone think anything Citi says is more credible than pronouncements from the most obsure tin foil hat? That pathetic firm wouldn't even exist without bushels of money from you guys.

That's precisely the point. Citi, GS, JPM, and all the rest of the top feeders are government sanctioned entities. It's like Citi raising interest rates on 2 million people to 29.99% yet being under government control. That means Obama and his henchmen are directly allowing such theft.

Hell, GS doesn't even try to hide the crime anymore. Look at Another View At Goldman's Trading Perfection And Statistical Improbabilities and tell me that this would be normal in any real market. The rich no longer care and are flaunting it in everyone's faces. And the bulk of the rest of humanity apparently plan to passively accept their new roles as eternal debt slaves to their new masters.

Yes, we needed to get rid of Bush and the Republicans but anyone who thinks Obama and the Democrats are the answer has rocks in their head.

Well, as lenin so acutely observed:

They can't help it, the dollar signs will blind them.

Of course, some political literacy will be needed, but the sheeeple are learning everyday.

Good Grief! At least they are being honest.

The 99%/1% is nonsense. In fact GINI world-wide doesn't have any clear trend. Also, the super-rich earning so-and-so many percent of total income doesn't mean they consume as much. Mostly, they invest the bulk of their income.

That isn't Citigroup who is claiming anything - it's a few analysts that may have been paid or employed by Citigroup.

It's published under Citigroup's name. If they wanted to disavow it, they could have done so yet they never did. The document is from 2005 yet there are numerous additional documents, again with Citi's name on them, from the following years also discussing "plutonomy". If Citi didn't want their name used like that, they had an easy remedy yet they never chose to use it and instead continued the discussion.

Thanks for an interesting post.

There is one thing I have wondered about shale gas or UNG (Unconventional Natural Gas) in general, and that is if these wells also yields NGL's (Natural Gas Liquids)?

And if so, is NGL yields comparable to "conventional" gas fields?

I do not know of a shale gas play that produces wet gas.

The Horn River play in NE BC produces dry gas.

It would be an interesting intellectual exercise to determine when and how ....

Rememeber, oil and natural gas liquids are found in the minds of men, but NGL's are found when you discover wet gas.

Enterra has an unconventional carbonate play in the Hunton Fm in the Anadarko Basin in Arkansas which produces gas and NGL's. Not totally sure how it works.

the barnett shale yields an array of gas composition. the deeper part of the reservoir contains wet gas and still deeper, at least one company (eog) refers to as the "combination" (gas and condensate)area.

the haynesville shale yields dry gas only, as far as i know.

Petrohawk Announces Third Quarter 2009 Financial and Operating Results

http://finance.yahoo.com/news/Petrohawk-Announces-Third-prnews-326543564...

about the haynesville:

Another aspect of this I'd like to know more about is the potential shortage of manpower/materiel if we wish to displace coal with more NG in electrical production, or petroleum in transport. This is reportedly an issue in the petroleum industry, with engineers retiring and so forth; is it also an issue with domestic NG production?

A very broad and general answer KLR: don't worry too much about manpower and equipment. Not that the concern doesn't have merit but there are more critical issue: capital availability and market stability are amongst the biggest. if the money/incentive is there the smaller problems can be handled.

Well, Scientific American has another piece in the November issue postulating a totally renewable future - cheaper than what FFs deliver, too - no doubt this will make it to the front page. It's big picture time again. So the question of whether we have enough qualified engineers will come up once more, I'm sure. You need someone to make sure those 50k+ holes we're punching every year are worth it - right?

"Petrohawk Energy Corp. Q3 2009 Earnings Conference Call"

http://seekingalpha.com/article/171655-petrohawk-energy-corp-q3-2009-ear...

Dick Stoneburner

and later...

Ben Dell - Bernstein

and later...

Ben Dell - Bernstein

Interesting! Sounds like they are having some second thoughts about trying to pump up production beyond natural limits.

this gets curiouser and curiouser.

http://petroleumtruthreport.blogspot.com/

You ought to post this on the 11/7 Drumbeat thread. It's a prime example of the pressures that media companies are under from advertisers.

yeah, did you get the excel file i sent you ndbakken ?