Peak Demand or Peak Consumption? A Look at OECD Oil Demand

Posted by Sam Foucher on November 11, 2009 - 10:19am

Standard economic principles have demonstrated that price is a function of supply and demand. The same is true for the recent oil prices fluctuations we have witnessed over the last few years, namely the equilibrium between supply and demand. However, the following conundrum has not been resolved: are oil prices high due to greater demand or too little supply? This ambiguity allows for vastly divergent interpretations of the same data and depending on the agenda you are trying to push, will easily support either.

Lately, the concept of "Peak demand" has been suggested in a multitude of recent articles that unfortunately do not qualify their analysis of the status quo. Some suggest that we are willing to and capable of moving away from oil. Are we?

A few years ago, some analysts lectured us about the effect of oil prices on the creation of new oil supply. Now that this argument has clearly failed, they have decided over night that we don't need oil anymore. In this debate, it is important to distinguish between demand (what you want or need) and consumption (what you get based on your ability to buy). Following this logic, consumption is "satisfied demand". Conversly, we can define the "unsatisfied demand" or "excess demand" that has been suppressed. Below the fold, I'll show that the key driver behind the price increase since 2002 has been excess demand combined with unresponsive supply.

OECD Demand

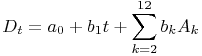

In this analysis, I follow an approach similar to the one proposed by Ye et al. (pdf) using a model defining a desired inventory level. The consumption trend observed between 1990 and 2001, when the market was well supplied, can be easily and accurately modeled by a linear trend taking into account monthly fluctuations:

The fit result is shown as the magenta line illustrated on Figure 1 below. The above model will define normal demand levels assuming low oil prices. The OECD consumption has strongly reacted to higher oil prices and is now almost 10 mbpd the level expected by my nominal demand model.

Figure 2. Observed OECD consumption and nominal demand model (monthly, total petroleum products), volumes in million barrels per day (mbpd). data from the EIA.

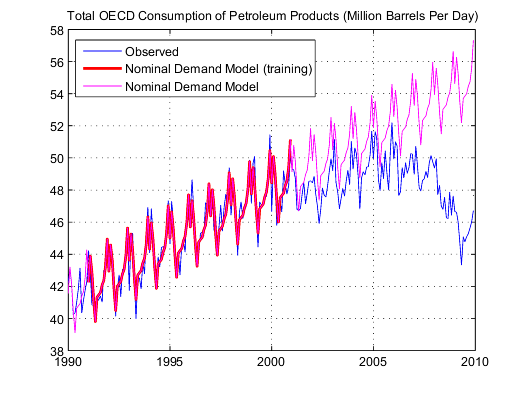

Looking at the residuals Ct-Dt, the fall in consumption from the desired level is even more telling:

Figure 3. Difference between the nominal demand models and the observed consumption (monthly, total petroleum products), volumes in million barrels per day (mbpd). Data from the EIA.

I make the

following assumptions:

- because oil prices were so low during the 1992-2001 period (i.e. virtually no excess demand), I will call "nominal demand model" the linear model defined above.

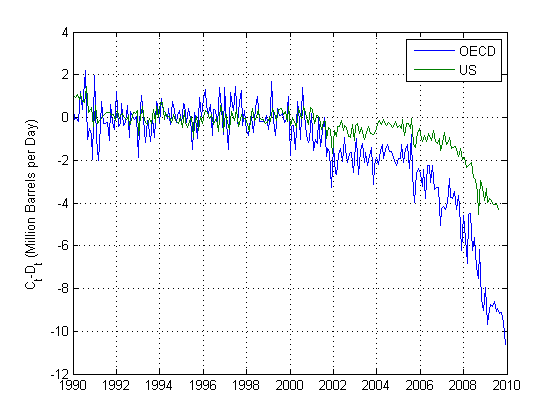

- The difference between nominal demand and observed consumption is an estimate of the excess demand: EDt=Dt-Ct

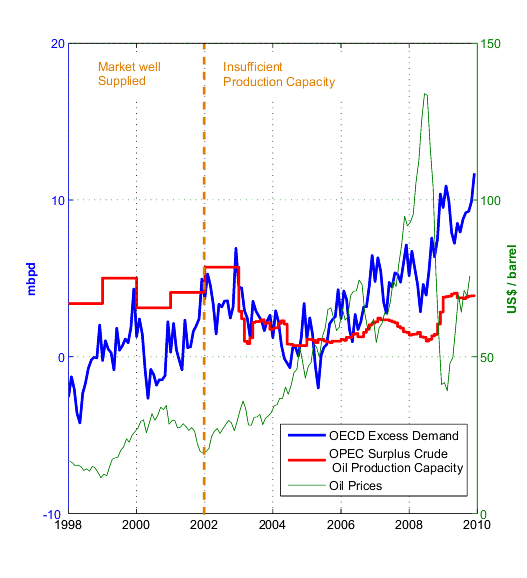

Plotting the excess demand against oil prices clearly shows why prices rose until the financial collapse last year. Before 2002, prices and excess demand were contained within a tight cluster around 20$/barrel - evidence that the market was well supplied and at equilibrium. The red line shows that prices increased by $20 per 1 million barrels per day of excess demand between 2004 and 2008.

Figure 4. OECD Excess demand versus oil prices (WTI).

One could argue that the nominal demand model defined above is not stationary and has been affected by structural changes in demand. Unfortunately, the only way structural changes in demand could be estimated is if the oil prices of tomorrow would go back to $20 a barrel for a few years within a pro-growth and healthy business environment. Only then could a new nominal demand model be estimated; those conditions won't be satisfied anytime soon.

Peak demand would suggest that the demand model would change over time, but then the level of unsatisfied demand would go down, bringing down prices with it. Actually, the severe recession we are currently in since the fall of 2008 has destroyed demand as a result of high unemployment rates and reduced credit availability. Looking at the price model on Figure 3, a return to the $70-80 range is equivalent of a demand destruction of around 3 mbpd for all of the OECD.

What about Spare Capacity?

Spare capacity, mainly provided by OPEC, is the amount of oil that can be made available within 30 days and sustained for at least 90 days (EIA definition). Looking at the available spare capacity and the excess demand estimate, it is obvious that OPEC spare capacity has become deficient since 2002, and that the surge in excess demand coincides with the increase in oil prices as shown on Figure 5.

Figure 5. Oil prices (right axis) and estimated excess demand along with EIA estimate for OPEC spare capacity (left axis).

So What is Causing High Oil Prices?

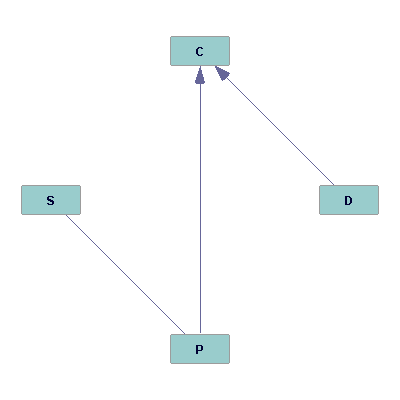

As an interesting exercise, I looked at the causation between oil prices and demand/supply indicators. Causal search algorithms systematically investigate patterns of conditional dependence and apply the Causal Markov Condition to reconstruct the graph of the data generating process (A good overview is available here). I define the following quantities:

- P: Monthly oil prices

- S: Monthly oil supply

- C: OPEC spare capacity (EIA)

- D: Excess demand

I used the remarkable TETRAD IV software (family of software for causal modeling originating with Peter Spirtes, Clark Glymour, and Richard Scheines at CarnegieMellon University) available online. I split the dataset in two periods: 1998-2002 period when prices where relatively low and 2003-2008.

1998-2002 period:

Figure 6. Graphical causal model for the period 1998-2002

Spare capacity is dependent on prices and excess demand. Prices and excess demand are independent unconditionally; but are dependent conditional on spare capacity. In short, OPEC spare capacity was playing a buffer role in order to absorb excess demand.

2003-2008 period:

Figure 7. Graphical causal model for the period 2003-2008

Prices is dependent on supply and excess demand. Supply and excess demand are independent unconditionally; but are dependent conditional on prices. Spare capacity is independent of all the other variables at 5% significance.

Conclusions

- Recession induced demand destruction (e.g. business going bankrupt, rising unemployment, etc.), or

- Long-term structural changes in demand (e.g. increase in the average car mileage, increase efficiency, etc.)

We have enough data from the OECD to draw the following conclusions:

- Sluggish supply growth is the main driver behind the 2002-2008 oil price increase. OPEC spare capacity has become irrelevant or at least unresponsive.

- Nominal demand is between 3 and 5 million barrels per day above production capacity.

- Prices are increasing by $20 for every million barrels per day of excess demand.

- OECD consumption is very elastic to oil prices.

- Non recession induced peak demand is not supported by the data.

- The financial collapse and the current economic recession has at least reduced demand by 3 million barrels per day for the OECD.

Thanks, Sam! This is really a nice post. Explains a piece of the puzzle that all of us have been wondering about.

Sam -- I'm sure all appreciate your effort. Took some time no doubt. A question that perhaps you can only answer qualitatively: China has been acquiring rights (via contracts and direct ownership) of oil production around the globe for some time. The volume is difficult to estimate but the amount would seem to represent a reduction in the supply side of your model at least for the rest of the consumers out there. Of course, it also represents a volume that China wouldn't have to acquire on the open market. Can you offer any hint to the potential magnitude of this situation with respect to your model?

I was supposed to look at it in this post but that was way too long for a single post, part 2 will be posted tomorrow and will look at the Non-OECD demand. I think the Non-OECD is effectively outbidding oil through various mechanisms (not open market mechanisms).

Great Sam. Looking forward to it.

Great article, keep up the good work. Could I also request in the future that parameters in formulas have a little one liner explanation?

Great post - it has clarified a few points I was wondering about.

"Some suggest that we are willing to and capable of moving away from oil" - I can see that those who are into wishful-thinking would like to interpret the recession induced reduction in demand as a signal we are safe from our dependence on oil. It is just that: wishful thinking.

(Now everyone can see why Sam does the mathematical heavy lifting on our joint papers.)

It probably helps to show some specific examples, especially in regard to the export market. Saudi Arabia, at least based on annual data through 2008, is world's largest net oil exporter; the US is the largest OECD net oil importer and China is the largest non-OECD net oil importer.

I think that the Saudis tried--as best they could--to restrain the price of oil from 2002-2008, and they significantly increased net exports from 2002-2005, but then from 2006-2008 their net exports fell below the 2005 rate, with 2008 (when oil prices averaged $100) actually falling below their 2004 net export rate (when oil prices averaged $42).

As one would expect, US consumption and net imports fell, in response to higher oil prices, but then we have China (their most recent data show monthly net imports of about 4.5 mbpd).

Saudi Net Oil Exports (EIA):

US Net Oil Imports:

Chinese Net Oil Imports:

Jeff,

I agree with your analysis, the part 2 (hopefully tomorrow) will look at the interaction between OECD and the Non-OECD (and it's not pretty)

Jeff,

I'm a bit confused concerning your chart that shows steadily dropping US net oil imports over the last 2 decades - What am I missing?

Check the vertical scale.

Net imports are positive. Net exports are negative. IMO, either those graphs to be labeled differently (ie. net export) or be positive.

You will have to talk to the EIA. In any case, they label Net Oil Exports as positive, Net Oil Imports as negative.

1. Higher prices have resulted in new supply. All that oil sands production and Brazilian ultra deep oil would not be produced if prices were $20 per barrel. Maybe you mean that the new supply resulting from higher oil prices has not been as abundant as analysts predicted?

2. Aren't consumption and demand the same thing. Demand (consumption) is a function of (a) oil prices and (b) available infrastructure to burn oil, among other factors. For every price there will be a different level of demand. In 2008, prices rose to levels which reduced demand (consumption).

Perhaps your definition of demand is different in that it ignores price and you define it as infrastructure available to burn X barrels per day of oil, which is not being run at full capacity. Therefore, because of idled oil burning infrastructure (such as airlines being stored in Arizona), your definition of demand is not being met. This is a non-standard definition of demand as it is more of a definition of infrastructure capacity to consume oil - which is vastly higher than 100 million barrels per day, compared to current consumption of around 85.

"Peak Demand" is the same as "Peak Oil" Supply, with the two linked via price.

Nope!

Demand, I'm really thirsty and need to drink four quarts of water.

Consumption, I've gone to the well brought up the water and drunk it.

Reality, there isn't enough water for all those have a need to be able to actually consume what they need.

/sarcanol

In your descripton, demand is the actual transaction (drinking the water), not the "need" to drink water, which is different from demand.

I guess despite the sarcanol tag my comment is still being over analyzed...

In economics, demand is the desire to own anything and the ability to pay for it and willigness to pay. (from Wikipedia)

If I'm very thirsty I desire water (need it) and if I have to drink and I'm able to, I will pay a premium for it!

Consumption is is the actual amount of water over time that ends up going down my throat. This actual quantity can be used to predict future demand.

If there is not enough water (not enough supply) to meet future demand,regardless of willingness and ability to pay, at some point you are actually going to die of thirst. You can't consume what is not available regardless of how much you might be willing to pay.

At least that's how I understand it but I'm *NOT* an economist.

A tidbit on the difference between Consumption and Demand from

http://www.sunysb.edu/sustainability/energy/facts/demand.shtml

Consumption vs. Demand

When speaking about electrical energy, there are two related, yet different, measurement parameters that need to be understood: consumption and demand.

Consumption is a more familiar concept for most people. Simply put, it is the total amount of energy used. Demand is the immediate rate of that consumption.

A simple analogy is a pile of rocks of various sizes and weights. Let's say that you were moving the pile. The total weight of the rocks is similar to the consumption because it represents the total energy you would expend. The weight of the largest rock is similar to the demand because it represents how much power you would need to have "available" to move that one rock at that instant in time.

Mathematically, energy consumed is represented by kilowatt hours (kWh). These are what the electric meter records as the dials turn. The rate of consumption would be kilowatt hours per hour or just kilowatts (kW). Typically electric demand is not measured for residential customers. However, commercial customers are charged for both the energy used and how fast they use it. The faster the collective customer base uses energy the more the utility must be able to supply.

How much energy the system must be able to generate to meet the instantaneous load (even if it's only for a short duration) is called its capacity. This concept is also used when designing a system or building so that electrical distribution equipment is properly sized. The capacity of a utility must be able to meet the demand so no customers are deprived of their electricity.

Everyone probably knows somebody who can't turn on their toaster and microwave at the same time without blowing a fuse. This example demonstrates a circuit that does not have the capacity to meet the demand. However, if these devices are operated one after the other, the energy would be readily available.

Rgds

WeekendPeak

Sp the problem with the electrical power analogy is that the electricity supplied "clamps" at the maximum power distributed. So you can only tell that people are requesting the maximum allowable; yet you can never tell how much they would use if they clamp was not there. I suppose there are ways to infer this based on how fast the requests increase (say in times of a heat wave) but the asymptote will never be known unless it stays below the clamp.

~

Unless the ground rules have been changed since the late sixties demand was defined as a FUNCTION of price ceretus parabus (sp?).

In plain language everything else held equal or staying the same, consumers might "demand" eighty five million barrells per day at eighty dollars a barrell .

At one hundred dollars a barrell they would use and "demand" considerably less, perhaps only eighty two million barrels.

If the supply is readily available the same consumers might "demand" one hundred million barrells at fifty dollars per barrell.(All these numbers are thin air numbers)

Obviously such models don't correlate very well with the real world but they do illuminate things well in a "snapshot " fashion.

"Things" cannot stay the "same " for very long of course.There are uncountable random and systematic changes taking place constantly and any big change in such an important part of the economy as oil supply is sure to set numerous feedback loops in motion.

In the theoritical world suppliers are numerous and have the resources to expand production as prices rise.It is recognized that increased production will come at increased cost so as prices rise more and more marginal producers come into the market.A "marginal" producer is one whose costs are high and who can only survive in a high price market.

The producer or supply side of the model is also a snapshot model rather than a movie model.

Things cannot stay the same very long on the producer side of the supply demand model any more than they can on the demand side.

In the real world the APPETITE (I use this word for clarity) for oil is continiously increasing as we get wealthier and more numerous-we would all (enough of us, anyway) like to own a big house, a large fast comfortable car, eat strawberries and grapes in the winter , and fly to the sun or the snow as the whim strikes us.

We buy as much oil as we can afford.

Most wordsmiths are such clumsy workmen that the world is thorughly confused concerning these simple definitions in much the same way as inflation is differently defined by the man on the street, financial specialists/writers, and non specialist writers-run of the mill reporters,bloggers, commentators,etc.

Suppliers are in a more complicated situation.

In a "snapshot" description oil prices do correlate theoritically with price-on any given day, there is some shut in production or jusy about ready to go production that can come to market , or be withdrawn from the market, as the price goes up or down,making it either profitable or unprofitable as the case may be, to produce these last few marginal barrels.

But the world is a movie, not a snapshot.

And while the pastors of the Church of Progress and Perpetual Growth assures us that supply can grow forever the folks who study such worldly subjects as biology and geology are pointing out that since the earth is not infinitely large, then the supply of oil must necessarily be limited, excepting the possibility (zero or close enough) of abiotic oil.

Any serious recreational fisherman knows how this game plays out-the big fish near home are the first to become scarce.Then you burn a little more gas in bith the truck and the boat to fish a second class lake. getting less fish per hour and per dollar invested.Third class lakes pay an even poorer return on the fishing hour and fishing dollar invested.

I go to the trouble of putting this up not to insult the regulars who post comments but for the unknown number of ordinary people , many of them well educated, who can make little or no sense of arguments using technical language with which they are unacquainted.I estimate the number of these people at somewhere above eighty five percent of the population of the US.

The easy oil is gone.The tough oil is obviously too expensive to produce to come to market at todays prices, else it would be on the market, allowing for the necessary time lag.The old fields are rapidly running dry.The population is growing , not shrinking.

Substitutes for oil , or near substitutes, such as the electric automobile , will take years of "movies" to have any real effect, if they ever do.

Conservation efforts will at best slow the arrival of the worst effects of continually declining production and continually rising prices.

TSIS in TF.

It may take the public another year or two to realize it.But in historical terms a year or two is but the blink of an eye.

This is as near to plain language as I can get.

Sam has done a fine job without a doubt.But the last time I had to solve a calculas problem was around 1970.I could , with the help of a text book or two, and maybe a few minutes tutoring here and there really follow his arguments SPECIFICALLY, rather than generally.

I expect that even most of the regulars here are in the same boat, excepting the engineers who are numerous , in relation to the number of folks who post comments.

damn mac, that was beautiful. your existential bend gets more direct daily. reminds me of camus's the Stranger story, you empty us of hope, which is something we all need to do, and open our hearts to "the benign indifference of the universe." the "howls of execration", by the masses is assured.

OFM, that was a lot clearer than how I was trying to say it!

Economical demand is being able and willing to pay for the goods.

Those who can not pay becomes irrelevant for the running part of the economy.

And conversely, also.

Regarding Canada and Brazil, at least in regard to 2008 data when US oil prices averaged $100, Canadian net oil exports fell, relative to 2007, and Brazil was still a net oil importer.

Supply needs more than a few months, and often years, to react to prices. This does not mean that the link between higher prices and increased supply is broken.

Prices are just part of it-higher costs are just as important.

Texas & the North Sea accounted for about 9% of total cumulative oil production through 2005, and their respective peaks are lined up with each other (1972 for Texas and 1999 for the North Sea). The initial nine year production declines in both cases corresponded to roughly ten-fold increases in oil prices. Based on the logistic models, mathematically Saudi Arabia in 2005 was approximately at the same stage of deletion at which the prior swing producer, Texas, peaked in 1972 (and like Texas showed lower production in response to higher oil prices), and world conventional production in 2005 was at about the same stage of depletion at which the North Sea peaked in 1999.

Incidentally, some preliminary work that Sam has done shows that if we look at the North Sea oil fields whose first full year of production was 1999 or later, i.e., just coming on line, these 1999 and later oil fields showed peak production of one mbpd in 2005 (as total North Sea production fell from about 6 mbpd in 1999 to about 4 mbpd in 2008). So, you are technically correct that there was a supply response to the rise in oil price, but was there a net increase in supply?

And as I have pointed out, once or twice now, Texas & the North Sea were developed by private companies, using the best available technology, with virtually no restrictions on drilling.

One argument I've come across is that cheaper overseas oil led to a lack of investment in the US, hastening the peak. This does nothing to explain why the madcap drilling of the 1980s did little to raise lower 48 production much. Here's a telling quote from a 1972 news clipping as well:

The Bulletin - Mar 17, 1972 The cornucopians would tell you this was indicative of that lack of investment as well - OK, how much difference would it have made, with that groovy out of sight skyrocketing late 60s demand? Are these Lynchs and Hubers seriously suggesting the US should be producing 10 mb/d today if only these detestable command economy types would have let things well alone? And how would they have dealt with the glut coming East Texas in the 30s that led to the TRC stepping in in the first place? Free markets weren't working at all in that atmosphere.

For that matter shouldn't have all that prorationing stretched things out further than normal in the first place? Funny how they use that as an argument for continued OPEC production but somehow it doesn't apply to Texas.

Texas had its biggest drilling boom in state history in the latter half of the Seventies, into 1980, with a fairly high rig utilization rate until the big price drop in 1986.

KLR -- I can tell you from firsthand experience what that "madcap drilling" of the late 70's+ drilling boom accomplished. I started working in 1975 so I was there for the build up to the collapse. Those high oil prices and skyrocketing drilling rig count did more to damage the oil industry then any event in my 34 year career. The rig count topped out at 4600. And I promise you at least half those rigs were drilling crap with little or no chance of success. Countless companies and drilling funds went out of business when the bubble burst. There may have been some improvements in production rates, especially NG since such plays had been grossly underdeveloped in previous decades due to extreme low prices. But for the money spent (actually wasted) the results were pathetic. And if you look at where most of the big gains originated it was in the Federal offshore plays in the GOM. Offshore drilling was just getting big in the early 70's due to technological advances. Those days are now long past. In recent times the Deep Water plays are mimicking that profile. I believe DW GOM accounts for 40% of offshore oil production these days. There's more to drill out there but their day will pass just as it did for the shallow water trends.

IMHO anyone who harbors great expectations that a spike in oil/NG prices will generate a cornucopian boom in production will be just as disappointed as all those folks who lost big time back in the 70's boom. In fact, I'm a little surprised that the boom of the last few years didn't draw in a lot more "stupid money" (that's is actually the technical term we use for those types of investors). Perhaps the boom didn't last long enough. Or maybe the memory of that last slaughter still lingers.

Yeah, I've graphed out US lower 48 production and imports and you can see how all those holes led to a very minor uptick, nothing to write home about at all. Here's an outstanding analysis of that era: Relationship of Oil Drilling and Oil Production. Maybe the Lynch mob will then say that tech has advanced to the point where we can make real gains this time, via 4D seismic, horizontals, etc. Think there's any validity to that? It hasn't done much for all the workovers in the interim, US production declines something like 145 kb/d every year average. Although the onshore average is gentler I'd imagine. The Obama administration's hostility to O&G won't help that, though.

It really strikes me as if the current administration is kicking the spurs to get to the next energy crisis that much quicker. Are they trying to stave off the worst of AGW? Or figuring that the sooner we get it over with the better? People talk about the financial crisis in those terms, after all, or dealing with the flu for that matter. It's not surprising at all that we don't get flat out pronouncements about their intentions.

I think its just that their recruitment pool is heavily dominated by the crowd that thinks all Oil and Gas companies are evil. And clearly, politically these companies have largely been helping their opposition, so it is only natural that their biases tend in the anti

direction. Then they have their base of supporters, who are vehemently against offshore.

Secondarily, compared to the drill-drill-drill party, even a well balanced approach to the subject would create a lot of selfserving whining by the industry. So at least a part of what you are picking up on probably comes from that dynamic.

The dispersive discovery model assumes an exponential advance in technology leading to an exponential advance in search rates. It doesn't help because the role of diminishing returns more than cancels that effect out. It is striking on how the math works out on this.

Excellent observation, and one that is well supported by the geologic evidence:

From "Environment, Power, and Society for The Twenty First Century: The Hierarchy of Energy" by Howard T. Odum

Cheers,

Jerry

+1

Good link KLR...thanks. Actually there have been significant advances but I don't think those cornucopians would like the second part of my answer. Hold your breath and hear me out: oil/Ng has NEVER been easier to find or more efficiently produced then today. On the exploration side 3d seismic has been truly magical. But 3d seismic has killed more potential drilling projects then it has aided. This technology is so powerful today that most operators, especially in the offshore arena, won't even look at a deal let alone drill it if there isn't 3d control. But being so much more efficient in the exploration process doesn't mean you'll find that much more oil/NG. Just means you'll be more efficient at it. You can't find wasn't isn't there. But we can find/produce what is there with much fewer wells. That's one reason I doubt we'll ever see the stupidity of the 70's drilling boom repeated to the same degree. Then a lack of concrete evidence allowed rampant speculation. Not very easy to do now with the new exploration tools.

Same goes for the production side. Horizontal wells have been another magic trick. Such wells can increase the ult recovery in many reservoirs but they do so at such a high production rates they give the illusion we've found much more then there really is there. Some secondary recovery applications for sure but the cream has already been produced. A little, but often very profitable, bump.

A far as hostility towards the oil patch from DC or the general public that's pretty much a non-issue for us. We've been those "evil greedy bastards" since at least 1975 when I started. We don't even hear the verbiage anymore. And to be brutally honest, the last thing the oil patch needs is for the gov't to "help" us. Just look at how well they've helped the rest of the economy.

That is a very good paper because it shows the phantom effects of cutting up pieces of the pie, in regards to production per rig. There might be more slices but each slice is smaller.

I commented on it here before:

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/5811#comment-543959

The price of oil produced in USA from around late 1971 to about 1974 was 'capped' -

"...whatever the effects of the Vietnam War on the national consensus in the 1960s, confidence had risen in the ability of government to manage the economy and to reach out to solve big social problems through such programs as the War on Poverty. Nixon shared in these beliefs, at least in part. "Now I am a Keynesian," he declared in January 1971...He introduced a Keynesian "full employment" budget, which provided for deficit spending to reduce unemployment....

"He attributed his defeat in the 1960 election largely to the recession of that year," wrote economist and Nixon advisor Herbert Stein, "and he attributed the recession, or at least its depth and duration, to economic officials, 'financial types,' who put curbing inflation ahead of cutting unemployment."

Looking toward his 1972 reelection campaign, Nixon was not going to let that happen again.

So the central economic issue became how to manage the inflation-unemployment trade-offs in a way that was not politically self-destructive; in other words, how to bring down inflation without slowing the economy and raising unemployment. One approach increasingly seemed to provide the answer -- an income policy whereby the government intervened to set and control wages...

in May 1970..Arthur Burns, whom Nixon had appointed to be chairman of the Federal Reserve....declared ...The economy was no longer operating as it used to, owing to the now much more powerful position of corporations and labor unions, which together were driving up both wages and prices.... fiscal and monetary policies were seen as inadequate. His solution: a wage-price review board,...who would pass judgment on major wage and price increases.

A second issue was also now at the fore -- the dollar. The price of gold had been fixed at $35 an ounce since the Roosevelt administration. But the growing U.S. balance-of-payments deficit meant that foreign governments were accumulating large amounts of dollars -- in aggregate volume far exceeding the U.S. government's stock of gold. These governments...could show up at any time at the "gold window" of the U.S. Treasury and insist on trading in their dollars for gold, which would precipitate a run.

The issue was not theoretical. In the second week of August 1971, the British ambassador turned up at the Treasury Department to request that $3 billion be converted into gold.

...Out of this conclave [Camp David retreat, 13-15 August 1971, present Nixon plus 15 advisors] came the New Economic Policy, which would ...freeze wages and prices [for a 90-day period] to check inflation. That would...solve the inflation-employment dilemma, for such controls would allow the administration to pursue a more expansive fiscal policy -- stimulating employment in time for the 1972 presidential election without stoking inflation.

The gold window was to be closed...But this would accentuate the need to fight inflation; for shutting the gold window would weaken the dollar against other currencies, thus adding to inflation by driving up the price of imported goods.

...After the initial ninety days, the controls were gradually relaxed...

Nixon won reelection in 1972. In the months that followed, inflation began to pick up again in response to a variety of forces - domestic wage-and-price pressures, a synchronized international economic boom, crop failures in the Soviet Union, and increases in the price of oil, even prior to the Arab oil embargo.

Nixon...reluctantly reimposed a freeze in June 1973. Government officials were now in the business of setting prices and wages. This time,... the control system was not working. Ranchers stopped shipping their cattle to the market, farmers drowned their chickens, and consumers emptied the shelves of supermarkets.

...Only one segment of the wage-and-price control system was not abolished -- price controls over oil and natural gas. Owing in part to the deep and dark suspicions about conspiracy and monopoly in the energy sector, they were maintained for another several years....

The oil-price-control system established several tiers of oil prices. The prices for domestic production were also held down, in effect forcing domestic producers to subsidize imported oil and providing additional incentives to import oil into the United States."

snipped from 'The Commanding Heights' by Daniel Yergin and Joseph Stanislaw, 1997 ed., pp. 60-64.

But the price of imported oil wasn't.

When the domestic price cap was lifted, USA oil operators were 'dropped back into' an environment where previously uneconomic oil plays were now economic, due to the sudden 100% exposure to market rates for oil.

Lower 48 as a group(excluding Alaska, Prudhoe Bay) peaked about 1970.

High international oil prices were a boon. Yet pickens were slim as production continued to fall...

Lorenzo

Canadian National Energy Board data, crude oil exports, millions of barrels per day:

2006: 1.80

2007: 1.79

2008: 1.79

2009: 1.80 (to date)

See: http://www.neb.gc.ca/clf-nsi/rnrgynfmtn/sttstc/crdlndptrlmprdct/ttlcrdlx...

Generally pretty flat.

Suncor had a major maintenance shutdown and an upgrader fire at its oil sands facilities in 2008, so it couldn't step up production to meet demand. The thing is that oil sands production cannot be ramped up on short notice. It takes years to start up a new operation.

Re: Higher prices have resulted in new supply.

Yes it did but by far too little to match excess demand, looking at the EIA production capacity estiamte, it has increased by 0.610 mbpd per year between 2007 and 2009.

Re: Aren't consumption and demand the same thing

No, they are different concepts in economy but they are very often used interchangeably, Demand signifies the ability or the willingness to buy a particular commodity at a given point of time. For instance, kids have a high demand for candies, however candies are not available all the time and consumption is low most of the time but when available, stocks disappear almost immediatly :).

Re: Perhaps your definition of demand is different in that you define it as infrastructure available to burn X barrels per day of oil

Yes, you can see it that way, imagine that oil will go back to $20 a barrel tomorrow for the next 6 months, the resulting surge in consumption would give you an indication of the level of demand that was suppressed (assuming that other exogenous factors stay constant).

Unfortunately, demand is not a truly measurable parameter and does not have any absolute scale associated with it. It is at best inferred. This has always been my problem with economics. I deal with this in my oil depletion modeling by saying that demand is some monotonically increasing stimulus, essentially equivalent to a "greedy" algorithm, and watching perturbations on the output to detect shocks to the system.

If you can get info on demand from rank estimators (qualitative high, medium, low demand, etc) or from proxy quantities then you can include this in the model I would think. The proxy for demand for candy would be how loud the kid screams for candy (measured in decibels), for example.

The fact that we only have this one great unknown of demand makes it the carrot on the stick for us modelers. Hey, its only one unknown, how hard can that be? Never mind all the game theory, Nash equilibrium, and other psychological factors that play into demand.

True enough. In the "real world", demand often has to be created. For a while, there was a large "demand" for whalebone corset stays. That has largely collapsed.

The other thing that is not included in these models is "need" -- which obviously (intuitively, I guess) is not the same thing as "demand", but can often be confused and conflated.

Clearly, we don't "need" as much petroleum as we "demand", but there is some lower limit below which civilization as we know it can not continue.

"Demand" seems to have more to do with making money, while "need" can probably be calculated, but has to do with survival. OTH, most people don't just want to survive, they want to make money.

Recently I was fascinated to learn that the "Austrian School" of economic thought (von Mises, Hayek, et al.) holds the belief that it is foolish to try and mathematically model something as complex and un-quantifiable as human behavior. They eschew econometrics in favor of theories based on deduction:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Austrian_School

Cheers,

Jerry

Very interesting Jerry. The thought got me thinking about the "future unknown/yet to be discovered" oil/NG reserves some folks "model". Until the latest revelation about the influence others have had on IEA estimates perhaps many thought this was a process that wasn't dominated by the "human behavior" to which you refer. I can offer that any estimates of reserves (past, current and future) is very much dominated by human nature even without outside forces coming to bear.

There are some very skilled analytical thinkers here at TOD who offer great insights. But they generally start with some base numbers offered by geologists and reservoir engineers. But some of our most critical assumptions utilized to initiate the analysis are completely arbitrary. That doesn't mean we should dismiss such modeling out of hand but realize that there exists a huge range of initial condition assumptions.

A very simple but completely accurate example of how we scientists come up with the "facts". There is the drilling prospect A. What's the probability of success? Virtually all such technical analysis begins with such a risk analysis be it drilling or the probability of some undiscovered oil accumulation existing in the world. And how do we scientifically come up with that number? We don't. We just pull a number out of our butt. Yes...we have an experience factor that plays heavily into the process. But that can just as often lead to a very biased and faulty decision. Prospect A looks like 2 similar wells I drilled but didn't work so I give it a low Ps. But another geologist who's drilled two similar prospects that did work gives it a high Ps. Both risk assessments are valid: they are based upon an honest analysis utilizing one's experience. But the both can't be correct. Or can they? Each geologist can present you his reasoning with equal support. Which one would you accept?

Then you get to the less tasteful situation. Geologist B doesn't think Prospect A isn't very good but he hasn't presented a drillable deal to management in two years and feels his job is in jeopardy. So he assigns a high Ps. Why not? If it works he saves his job. If it doesn't he's out the door (or not...geologic failure is often more readily forgiven then the failure to generate). Consider the choice an IEA analyst might face: provide his manger with a number he knows he really can't generate accurately or tell the boss there is no answer to his question. And this doesn't take into account any additional pressure he might feel if he knows his boss already has an answer he wants to see. This is the main reason I try to avoid debating the outcomes (at least on a quantitative basis)of all the different resource models presented on TOD. While we do have a good number of great analysts here their conclusions often hang upon the validity of the initial conditions presented by geoscientists. I've watched honest and smart geoscientist generate vastly different answers to the same data set. We are not mathematicians. Geology is basically an observational science. And what any person observes is very much dominated by their humanity. Ask anyone wrongly convicted of a crime based upon the honest(in their minds) testimony of a eye witness.

Thanks Rockman,

That is a very insightful comment, thanks for taking the time to share your experience. The dependence on initial assumptions is spot on. In my readings on system dynamics modeling much the same point is often stressed, namely that a model is really only as good as the assumptions that go into the design of it.

The authors of "The Limits to Growth" took great pains to explicitly state their assumptions for that very reason, and they challenged anyone who disagreed with their analysis to present an alternative model with all initial assumptions also made explicit. Unfortunately that never happened, and they were attacked largely for ideological reasons instead. I think it was Paul Krugman who recently admitted that economists in particular were miffed because the team from MIT didn't ask them first.

I wonder now what an analysis of energy discovery and production based on logical deduction would look like.

Cheers,

Jerry

Krugman's comments can be found here:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/04/22/limits-to-growth-and-related...

Krugman states:

Where "Limits to Growth" was criticized was for how it treated price-feedbacks. As I understand it, the equations underlying LTG weren't made available until two years after the original publication.

I also heard that no one else was able to duplicate the LTG results as the model was complex in its connectivity. One of the hallmarks of good science is reproducibility and openness, but I would say that the original LTG team was too inscrutable.

Hello WHT,

If anyone is an expert on inscrutable it would most certainly be you!

Cheers,

Jerry

No offense taken, but I at least keep my models concise and post all the code. I know enough not to create a monstrosity like the world dynamics model.

Of course it takes some work to achieve a degree of conciseness and to understand it, but that is never easy, otherwise someone probably would have already done it.

Yep, that's it, thanks for the link.

That's probably a common misconception. The book "Limits to Growth" was just one of three reports to the Club of Rome, and only ever intended to be a summary of the research project. The 630 page volume titled "Dynamics of Growth in a Finite World" is the extensive report that contains the detailed description of the mathematical model and the research behind it.

For those who didn't want to wait for that third report it was certainly no secret, as Krugman points out, that the model used was based in no small part on the equations published in Jay Forrester's book "World Dynamics".

Cheers,

Jerry

WHT ...

You could measure investment in infrastructure as a factor. The analogy is someone paying $50,000 for a car will tend to drive it. Chances are the vehicle in question won't be driven 24 hours a day, like a taxi, but it will be driven frequently and persistently- the process is multiplied. Add the cars plus highways, trains, roads, bridges, airports, etc. (quantities) and there is an envelope for fuel use. From the factor, parameters can be set.

I don't know if the exercise is worthwhile. Can a good model be created? Probably, but it's safe to say that from here on in, demand will outstrip the available supply regardless.

Any chance this post could be sent to Energy Secretary Chu and the members of The Obama administration who are tasked with national economic policy. I'd like to send it to members of my local city council but my recent experience with them is that they are too stupid to understand what is so plainly obvious from this post.

My experience with the local City Council, and my suspicion about Sec. Chu, etc., is that they are far from stupid or ignorant about these matters-- they know perfectly well what is going on, and they know that if the bubble isn't kept inflated we are all doomed.

It appears that their hope is to reduce expectations faster than credit and energy supplies evaporate so that a "soft landing" can be achieved, and general social chaos avoided.

It looks to me like they are succeeding pretty well. The "stock market" is up, the Bear Stearns guys got off by a jury of their peers, people are driving to work if they have jobs, or are staying home watching TV if they don't. No sign of unrest out there.

I think we can both safely agree the Secretary Chu, is neither stupid, nor ignorant about reality.

However while your city council members may be highly intelligent and knowledgeable, as far as mine are concerned, I beg to differ. Unless they surprise me by winning Oscars for their acting... ;-)

Thank you for this work. "Peak Demand" by the OECD as maintained by CERA et.al. seems to be a smokescreen to avoid coming to grips with anemic supply - e.g., global peak.

Regarding the "Long-term structural changes in demand (e.g. increase in the average car mileage, increase efficiency, etc.)," I would emphasize SUFFICIENCY as the ultimate

aim of demand side efforts.

Sam, great post.

However, now you are getting the economists in a tizzy and there will be a flood of arguments over definitions of terms, and trying to expand the model.

Question:

is not supply also a function of marginal cost of production

i.e. there are fixed and variable costs. If the price is below variable cost, they shut down.

My point is that the current $75-80 price is partially a function of the US dollar decline, and the distortions it causes.

One of the presenters at ASPO was the Scottish investment banker (oil futures trader) who described current market oversupply conditions, which are persisting, yet we have 75-80 price, despite many analysts saying the price should logically crash to 20 to clear the market.

I suggest we have good supply/demand balance now, as reflected in stable price.

I suggest we have only had imbalance (that is greater demand than can be met by immediate supply) very rarely in the past 50 years. Once was in 1973, and once was at the end of 2007 - mid 2008. The incline of the price curve changes dramatically at those times.

Re: now you are getting the economists in a tizzy

You're probably right, I'm not an economist and I don't pretend to be one, most of them would probably pull their hair reading this post. However, I could have used more "neutral" technical terms (like X and Y) to describe what I'm doing but it would have not change the analysis that much, it does not take a Nobel prize in economy to see that the residuals from the nominal models is a good explanatory factor for the oil price increase.

Re: My point is that the current $75-80 price is partially a function of the US dollar decline, and the distortions it causes.

I think it is overstated as a long term factor (it may affects small time scale fluctuations however) and at least not a contributing factor of the same order of magnitude as excess demand.

Re: I suggest we have good supply/demand balance now, as reflected in stable price.

I tend to agree with that, the model above does not take into account GDP contraction which means less business, more unemployment, etc. therefore lesser oil demand. However, you'll see in part 2 that the Non-OECD demand is the elephant in the room.

I would be happy to get the economists in a tizzy. They are the ones that have screwed the pooch by not including resource constraints in their models all these years. What was that theory of substitutability the economists claimed would always save us from the resource problem?

I was recently talking to a well-regarded economist who specializes in econometrics recently and the "big finds" off Brazil was the rationale for ignoring oil depletion as a problem. All the major league economists will eventually have to face up to the fact that all their models are sunk-cost and they will have to come up with something new. They invented the idea of "sunk cost" dog food and now they will have to eat it.

As the noted philosopher Spinoza said "The concept of dog does not bark"

"I would be happy to get the economists in a tizzy. They are the ones that have screwed the pooch by not including resource constraints in their models all these years. What was that theory of substitutability the economists claimed would always save us from the resource problem?"

Thanks for providing such a clear example of the tendency for some people online to paint with an insanely broad brush, and therefore make ridiculous statements.

As I've pointed out many times online, I am an economist, and I've been on the "right" side of energy and environmental debates since day one. So don't stick me in the same pigeonhole with the myopic fools who got it wrong.

And let me fill everyone here in on a little secret: Economists are as upset with you (plural) as you are with them. The endless confusion between "demand", "quantity demanded" (yes, those two are different), and "consumption", are enough to make me break out my bottle of cheap red wine.

And when the talk starts about "is it supply or demand", I want to scream. It's both! Demand alone doesn't dictate prices, nor does supply alone. It's the interaction between the two forces. For a very crude mental model, consider a parachutist. The air resistance and gravity (among other factors) balance to result in a rate of descent. Changing just the force of gravity or just the effective resistance of the parachute will only have a predictable effect if you make the dreaded ceteris paribus ("all other things being equal") assumption. This is where so many people, particularly the doomers, go so wildly wrong: They have no apparent appreciation for the complexity and dynamic nature of markets. That's NOT code for "higher prices will always create the desired supply", but a simple recognition of reality. When market conditions change it kicks off a cascade of changes, including some new supply, some demand destruction, some technological change that creates new substitutes, and so on, that will ultimately result in the market reaching a new equilibrium, if it's left undisturbed by further shocks for long enough. In practice, we never reach a true equilibrium, but tend to orbit around one (think of an electron cloud), with the state of the market constantly jostled by minor changes.

I can't tell you all how many times I'm practically screaming at my monitor over the way many people make ridiculous, linear extrapolations and reach absurd conclusions. There's a term in computer science for that syndrome: GIGO (garbage in, garbage out).

I think I understand, or at least empathize with, your outrage. I feel the same frustration when non-medical people tell me what my job should be.

However, I think it is unhelpful to scream at your monitor.

Writing posts on the OilDrum is more helpful. Even more helpful is to get out and talk to people, protest on street corners, write to the editor of the local paper, maybe even run for City Council.

Fundamentally, the knowledge that professionals of practically all disciplines have worked so hard to obtain is being trivialized and commodified by a giant marketing machine - think "Global Warming" for an example. This is no way to run a democracy. Thinking people -- those who want to solve problems together, rather than merely eliminate the competition -- need to take back the machinery of the state.

The whole rationale behind these economic equilibrium arguments is hotly discussed, not only in economic circles but in computer science circles. I mentioned the idea of game theory in another comment on this thread. These researchers claim that the equilibrium for price wars (and other human processes) may be intractable.

http://www.physorg.com/news176978473.html "What computer science can teach economics"

So you essentially have to blame Computer Scientists for usurping the economists' research.

Causal modeling of which Sam is attempting a little bit in this post is also prone to the explosion in states. Say that we had 70 parameters each with a possible outcomes of (low,nominal,high). Trying to find a maximum subject to some constraints in this space would require more calculations than the number of atoms in the universe (i.e. 703).

That is also elementary computer science and it explains why we often times concentrate on toy problems -- those are the only tractable ones. Of course there are other ways to make problems tractable, and those come under the umbrella of statistical mechanics and complexity theory. I have written up a TOD post on that subject and it is in the queue.

Game theory is a curious area. I was talking to an economist that uses game theory in his research about the article you mentioned and he suggested that game theory is normative rather than descriptive (i.e. "this is the way people should behave" rather than "this is the way people actually behave").

One of the "positive" aspects of the "economic crisis" is that critiques of mainstream economics that were dismissed quietly as heresy a few years ago are being aired again (see Mark Thoma's blog). These come from both theoretical perspectives (arcane issues around "aggregation" and whether economies are ever in "equilibrium") and recent findings within experimental/behavioral economics that contradict the rational agent model. Whether these discussions have any long term implications for either the discipline or the curriculum for freshmen economics courses remains to be seen.

Interesting. Normative is also the province of software languages, where you are restricted in what you can accomplish. So what happens if in the future all price wars are settled by computers, which are limited by algorithms written by this same set of normative rules? It makes you wonder how the rational arguments will change. If they used the same software, say the Bloomberg machines, then a true equilibrium can be predicted just by understanding how the software works.

The problem is that some equilibrium may exist whereas one person has all the money :)

BTW, in my comment above that should be 370 not 703 combinations.

But I would not expect that particular equilibrium to be very long lasting due to the fact that there would be a lot of external forces acting to push it past a tipping point.

Actually, feudalism, where an extremely small set of the population own absolutely everything including everyone else, has had longer periods of stability in history than the relatively short periods in western history where income was (by all historical standards) fairly evenly distributed.

If there is one area where modern economics certainly fails in the application, it is in the interaction between economic and political power, where economic advantage is used to secure political advantage, which further entrenches economic advantage. Usually economists seem to simply ignore this,.

True enough but that was before the cat got out of the bag. We may even eventually revert to such a stable system, however I don't think it would fly right now that all the serfs have grown accustomed to their comforts.

Lou,

Good to see you are still reading TOD. I appreciate your nuanced statements in defense of economics despite the real worries of a depleting, finite resource such as oil. My mindset has always been to "embrace the complexity" as a way to understand the world. Many people don't seem capable of that approach - not a slam we are all just wired differently.

So were you screaming at your monitor about Sam's post or did he do a pretty good job of describing the drivers of supply, consumption and price of oil for us lay people?

I have a post in the TOD queue that includes that same phrase "embrace the complexity". I guess it is a bit of a catch-phrase, yet the whole philosophy behind coming up with a concept such as entropy is as a way of dealing with complexity and uncertainty. As a way of understanding the world, I would certainly agree with you.

For example, many of the Black Swan "fat-tail" models that are currently displacing the "Normal" statistics models derive from entropic considerations. I can usually detect the entropy in certain graphs based on what the underlying mechanisms are, whether it be dispersion or some other randomized phenomena.

OK. Here is the equation from the Ye paper that Sam references:

Does anyone else see the circular definitions in these equations?

What else to conclude other than demand is totally inferred from the other measured variables.

The reality is that your terminal velocity analogy is pretty bad. All those physics parameters have measurable properties and nothing is inferred.

So we got the economists in a tizzy :)

As a physical scientist, ridiculous statements such as this make me want to break out my bottle of the good stuff. Back away from the physical analogies and nobody gets hurt.

Given that EIA and IEA have essentially been "linearly extrapolating" GDP growth to predict future energy demand, Sam's approach appears reasonable. Would you be willing to recast Sam's observations in Figure 2 in the words of an economist?

Not only physical scientists would question this, but statisticians as well.

The "orbiting around a cloud" analogy is essentially the old Normal statistics with a narrow standard deviation approach that people like Taleb are discrediting. Dig deeper and you find lots of phenomena that don't follow Normal statistics.

The obvious one in my mind is what happens if multiple economies start to appear due to ELM considerations. All these economies will take on more dispersed trajectories depending on their own individual resource constraints. There is no true equilibrium here in the sense of a global economic picture, only an aggregate of paths.

LouGrinzo,If I had seen your post before I put mine up I would have left the clarifications of misinterpreted basics up to you.

Sometimes I am suprised that we are ONLY as confused as we are.

I will bet a hundred bucks that if you stop a hundred college students at random on thier way to a football game at any really large university that not over fifty percent of them can define "function "in the mathematical sense.

Yours was clearer and, frankly, more accurate, if not overly concise.

Cheers

The Jay Hanson articles that are posted here typically include ridiculous claims about what economists supposedly believe. I'm convinced that he is being intentionally inflammatory and no longer bother reading his writings. If he can't get that much right, what reason do I have to believe he gets anything else right either?

Beyond that, I have mixed feelings about the public treatment of economists. I would prefer to see more humility on the part of practitioners of the discipline, given that the much of the theory consists of a series of conjectures without substantial empirical support. Having said that, there have been instances of articles on these boards where non-economists have used economic concepts (e.g. GDP) without understanding these concepts sufficiently to do coherent analysis.

I would suggest that commenting broadly on conventional economics does not (and should not) hurt credibility too much. Its all a bit of a confidence game as you have little idea of whether the person pushing some idea or data doesn't have a hidden agenda. Theory is irrelevant if their goal is to make money (perhaps at your expense). There is so much of this going on now, and with the realization that it boils down to game theory, means that we shouldn't take it too seriously. That's why we can slam economists -- and financial quants -- hard. They should know how to take it.

In contrast, if I were to get something as fundamentally simple as resource depletion wrong, I would have to question my own credibility.

BTW, I don't read Jay Hanson either.

Lou, if the shoe don't fit then don't wear it. Anyway look on the bright side at least you're not a lawyer ;-)

BTW there is someone in my extended family who has a PhD in economics and works for the IMF, unfortunately he also happens to fit the stereotype. Ces't la vie.

"This is where so many people, particularly the doomers, go so wildly wrong: They have no apparent appreciation for the complexity and dynamic nature of markets. That's NOT code for "higher prices will always create the desired supply", but a simple recognition of reality. When market conditions change it kicks off a cascade of changes, including some new supply, some demand destruction, some technological change that creates new substitutes, and so on, that will ultimately result in the market reaching a new equilibrium, if it's left undisturbed by further shocks for long enough."

This sounds good until you come to the word "if" in the last sentence. That is one hell of a big "if" given what we are facing. At some level of stress, the "cascade of changes" model has to break down.

I think many doomers do appreciate the complexity and dynamic nature of markets. They have evaluated the future stresses (peak oil, climate change, greed) and concluded the markets won't survive.

Agreed. What many economists seem to define away is the possibility that there is a set of circumstances and forces that the system can't handle.

We had a simple example here in the Bay Area when a truck driver drove off the Bay Bridge this week and died.

The set of circumstances that caused the accident was that he was turning at too great a speed with a load of pears that may have shifted during the turn.

Had he driven more slowly or the load was smaller or the corner not as sharp or perhaps a little less of all the variables and the accident would not have occurred.

In our case, we have an economic system that demands growth on a finite planet (a sharp curve coming up when the system becomes even more strained) and a population that is demanding that growth returns (a driver stepping on the gas).

Given this set of circumstances, is there any way for this to end other than collapse?

I think we may have some analogs, which have happened during wartime. Sometimes a city or country is blockaded or cut off from supplies. How many of these (not directly involved in hostilities) have broken down into a mad max freeforall? I think the answer is very few. A lot of societies have faced declines more severe than I think post PO declines are going to be, and remained mostly intact. The only thing going against us, is they has an external enemy to blame, so the tendency was to work together to thwart the intentions of some evil enemy. In our case, the thing to fear is the blame game trying to find internal enemies to blame. In societies where that doesn't become an important part of the social/political dynamic, I think the transition will go OK.

"The only thing going against us, is they has an external enemy to blame, so the tendency was to work together to thwart the intentions of some evil enemy." Posted by Enemy of State

They also would have the advantage of being aware that the situation would likely persist for a relatively short duration. Within a few years at most, the embargoer/invader will either be repulsed, and the embargo lifted, or he will capture and occupy the place, after which at least basic supplies would again be available, even if at a reduced level. Resource depletion, however marches on relentlessly and permanently, only ending when there is finally no more of a particular resource that is available to be "depleted."

Antoinetta III

Oh, is that what is meant by "Tipping Point"? Which Then leads to a "Pear Shaped Collapse" Followed by a vertical plunge off a

cliffbridge?I, for one, would not mind if you repeatedly defined demand, consumption, supply, etc. every time they were misused, much as Jeffrey does about ELM every time there is a comment about production estimates.

If the way economists talk about supply and demand were accurate, thus useful, you'd be making a great suggestion.

Cheers

Well, great! There's an economist who actually includes reality in their thinking rather than believing blindly in the ever-supplying invisible hand. Thus, we should trust economics!

I think not. Few disciplines have done as much to mislead the global "we" than economics.

Most are idiots of their own construction. I will stand by that statement without even a hint of humility. Thank god a few Austrian School people are out there - though even they get it wrong with their love of markets.

You'd think someone would point out models created to model a period of unprecedented plenty don't reflect reality. How can so many people be so damned blind?

At the end of the day, I will (relatively) trust any field in aggregate. Geologists, physicists, physicians, etc. - at least at the theoretical level, if not the practice of their arts.

But economists? They are absurd until proven rational. This is known as being hung on one's own petard.

Cheers

Well, as far as I can tell, it's some combination of substitution and technological improvement that the economists think will save us. The premise of substitution itself is simply that at some point, there will be a price at which it will make sense to switch to a "backstop" technology. The added assumption is that research and development will eventually make that technology affordable.

I'm not sure that the economists are alone in this belief. My undergraduate degree was in physics. From what I gather in the limited conversations I've had about oil depletion with former classmates from that period, they don't seem to be particularly concerned, apparently mostly believing that some alternative energy source will allow a cleaner version of BAU.

I think there are two halves to this post.

The first half illustrates that the supply/demand divergence appears real. The monthly model was parametrically fit to demonstrate that the divergence from extrapolated trends could not be due to noise. You could almost see this from the underlying periodicity but it does show up clearly when a model is applied.

The second half of the post discusses what relationships are key to the high prices. The approach taken is to (naively and unbiased) assume that each indicator has some causal connection to every other indicator. Then the Tetrad software is able to reduce the interconnections to only those edges that show a high correlation. (The big if in all this is that correlation implies causation, but that is OK for experimentation) My question is whether the time delays between the various quantities is taken into account. In other words is this a transient kind of analysis or is it set up as an equilibrium model? This separates out causation as a temporal phenomenon or as pure feedback between the elements leading to an equilibrium.

I ask this because the first half of your post has a very sophisticated temporal model (down to the month) while the second half does not discuss the time aspects.

It also occurred to me that this kind of approach could be used to interpret the causality between CO2 and temperatures in climate change studies. Economics unfortunately has all the psychological factors associated with it, while physics should have only concrete physical causal relationships.

I quickly looked at the Tetrad site and found no example case studies. Impressive that you were able to figure out this software w/o the benefit of any concrete example or demos.

I'm still in my learning curve with the Tetrad software, I encourage you to play with it, the interface is very intuitive and it's launched as a neat remote java application. It implements various causal search algorithms that are reffering to a fairly large litterature, the one I used here is the Markov Blanket Search algorithm akin to an unsupervised Bayesian network construction using price as the target variable. I'm not 100% sure this particular algorithm is performing a preliminary vectorial AR analysis (VAR). I initially used a Granger-causation analysis based on a VAR analysis of the data over various times lags, the issue here is the short sample size (only 50 months) which makes the VAR estimation very noisy in particular when the proper model order is established with a BIC criterion.

So in translation, it appears that temporal causation is the key, otherwise the time lags would not need to be varied in the VAR analysis.

I will continue to plug away at Tetrad.

Here's the digg, reddit and SU links for this post (we appreciate your helping us spread our work around, both in this post and any of our other work--if you want to submit something yourself to another site, etc., that isn't already here--feel free, just leave it as a reply to this comment, please so folks can find it.):

http://digg.com/d319jMc

http://www.reddit.com/r/energy/comments/a3ad2/peak_demand_or_peak_consum...

http://www.reddit.com/r/Economics/comments/a3ad6/peak_demand_or_peak_con...

http://www.reddit.com/r/environment/comments/a3adc/peak_demand_or_peak_c...

http://www.reddit.com/r/worldnews/comments/a3adf/peak_demand_or_peak_con...

http://www.reddit.com/r/reddit.com/comments/a3ajw/are_oil_prices_high_du...

http://www.stumbleupon.com/submit?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.theoildrum.com%2F...

Find us on twitter:

http://twitter.com/theoildrum

http://friendfeed.com/theoildrum

Find us on facebook and linkedin as well:

http://www.facebook.com/group.php?gid=14778313964

http://www.linkedin.com/groups?gid=138274&trk=hb_side_g

Thanks again. Feel free to submit things yourself using the share this button on our articles as well to places like stumbleupon, metafilter, or other link farms yourself--we appreciate it!

Thank you for this post! The Tetrad IV link alone was worth the price of admission (reading), not to mention the other stuf:

Quickly:

- A(k) in your sum series is... ?

- 2001 as cut-off point was derived from D(t) trend break-down ?

- Fig 5. Why 2002? Why not 2003/2004 when the excess capacity and prices broke away from their previous levels (i.e. what is your criteria)?

- Conclusion 1.2: OPEC spare capacity. Unresponsive for now. Just as there was a trend between 2002-2008, there could be a new trend emerging. at least that's how many energy economists view the markets (e.g. OIES): trend equilibrium, disequilibrium, trend-formation, new equilibrium, repeat.

- Based on 1.2. one would want to ask the question: Why? Does 'artificial demand' (i.e. speculation) contribute to this at all? If so, the move from WTI to Argus ASCI might show something come next year)

- Conclusion 3: can the marginal cost growth really be roughly linear? This doesn't play well against the upstream cost curves I've seen thrown around by CERA and Goldman. What was your fit for the linear regression?

- Conclusion 6: Where does the -3Mbpd demand reduction come from? I can eyeball roughly a drop of that magnitude in consumption from Fig 2, but demand drop? Is it the Jun-08 to end of recovery (yellow dotted line) diff in Fig 4? How do you differentiate between price related demand adjustment (ongoing since 2002 till ? in your graph) from financial crises induced demand adjustment? Is it just based on falling vs rising prices trend? Or some price level cut-off? Maybe I'm thick, but I can't deduce this with certainty.

And now somewhat off-topic:

As for the argument "Unfortunately, the only way structural changes in demand could be estimated is if the oil prices of tomorrow would go back to $20 a barrel for a few years within a pro-growth and healthy business environment". I think the 'peak demand' argument from economists is an exercise in über-hubris.

What we might see then is new demand adjustment (or demand creation) that would mask any possible level of earlier demand destruction or negative demand adjustment (temporal).

In short, what I'm trying to argue - and I could be wrong - is that there is *no way* to know. It's just economical philosophizing : maybe destruction, maybe adjustment, maybe peak, maybe not.

In the end, it hardly matters, if it rebounds and whether we call it demand creation, demand re-adjustment or whatnot. It rebounded, demand went up. Price went up. Elasticity might be slightly different this time around, but probably not by much. Time would tell. I assume we agree on this last bit (that it doesn't matter that much).

I fully agree on the idea that if a true demand peak would happen, your test would be the arbiter on the demand peaking. However, it's a fairly unprovable argument from economists, as oil surely would come back in vogue if the price fell low enough comparative to alternatives. Money goes where the best opportunities lie - it's all relative to the price.

The whole demand peaking is a function of relative costs. To say demand has peaked for good includes the assumption that the forecaster knows the relative price levels of oil and it's substitutes from here to eternity. A bold claim, I might say (hence the claim about overconfidence).

Again, this is not against your model - I find the demand peaking a total diversion in the discussion. We'll know for sure in maybe 20-30 years. Not today. Forecasting it is even more futile than trying to predict the oil price alone to 2040, which is difficult enough as it is.

There might not be enough information to reconstruct the scenario, but the temporary demand destruction periods from the 1970's and 1980's might benefit from a historical revisiting using this approach. The contractions were of that same order back then.

Depends on your time format, but in my case A(k)=(k-1)/12

prices were fairly stable before 2001 and significant deviations from the model after 2001.

Depends on your criterion, start of the first ramping-up in prices was mine.

Possible but after almost 5 years of sustained high oil prices, no significant increase in production capacity makes you wonder.

With no data about speculative activities it is hard to give a definitive answer, studies about the future market are showing that speculators are trend followers (i.e. they change positions after price changes).

It's a rough approximation, an exponential fit would have been an overkill here I think.

That's very speculative at that point I think that business slowdown due to poor credit availability and rising unemployment has temporarily reduced demand by a significant amount (probably around 6 mbpd), meanwhile consumption has risen for a few mbpd for the last few months (seasonal fluctuation).

Thanks for the clarifications. I'm getting your flow of reasoning better now (yes, I'm slow).

Just for comparison, here's a couple of rough comparisons about production costs as a function of production rates or time:

CERA - upstream cost vs time

CERA - supply costs vs production rate

Booz Allen / IEA - cost of supply - marginal production

Goldman Sachs partial cost - time

Of course, I have no idea how they pulled the data together, so TIFWIW.

Now that I look at them again, it's difficult to say anything certain about the cost escalation trend, just by looking at the above graphs. It could well be linear increase for now and perhaps levelling off when a big enough resource base is utilized for long enough and costs get sunk.

Really looking forward to the non-OECD analysis!

Interesting stuff, although I think most of the readers (myself included) are a bit lost with the mathematical jargon.

I think a useful concept regarding the question of attribution (demand or supply) would be to estimate the elasticity of each separately, i.e. as a function of price, how does demand vary. And as a function of price, how does supply vary. Ignoring for now the time lags involved any imbalance should be met by some of each factor, and clearly the more elastic variable will change the most. I suspect that the price has changed (and probably will change enough), that using the log of the price rather than price would work better.

Then we have the issue for a given step function change in price (or log price) how does demand vary with time. Presumably there is a small amount of instantaneous elasticity, as people do things like drive slower and consoladate trips. Other adjustments such as moving closer to work, finding car pool partners, purchasing a more efficient vehicle take longer. Still other adjustment mechanisms might have even longer time delays -demand for electric cars is there (say), but won't satisfied until first battery research creates good batteries, then production can be built, then inventrory accumulates. So I suspect that the temporal elasticity of demand probably has some important time varying characteristics. And a similar argument could be made for supply.

Great post, Sam!

The "Peak Demand" argument has needed an analysis and an intelligent response for a while.