Where Is Oil Production Headed?: An Adverse Scenario

Posted by Gail the Actuary on March 4, 2009 - 10:22am

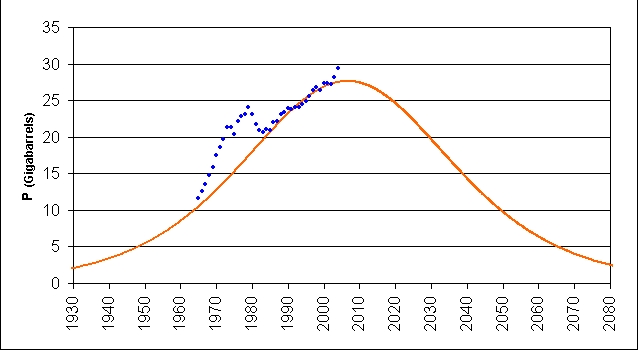

A lot of us have an image in the back of our mind of Hubbert's peak. Based on this peak, we assume that oil production will decline in much the same pattern as it rose. For example, in an analysis performed several years ago, Luis de Sousa shows this graph, based on the application of Hubbert's model to crude oil data available through 2004. Based on this analysis, he concluded that oil production was expected to peak around the Summer Solstice of 2006.

This graph is kind of scary, but it is also somewhat comforting. A person gets the idea that while there will be a decline, production will not go down too rapidly. Because of the apparently slow decline rate, it looks like we should be able to get along pretty well with a little adaptation--perhaps some electric cars.

I am concerned that the actual downside of the curve may look very different from the shape envisioned by Hubbert. The problem is that the limiting factor is likely not geology, but the failure of complex networked systems, particularly the financial system. Below the fold I show one view of what future oil production could look like, assuming the current unwind in world debt destabilizes the world financial system, and it becomes necessary to rebuild the system almost from scratch.

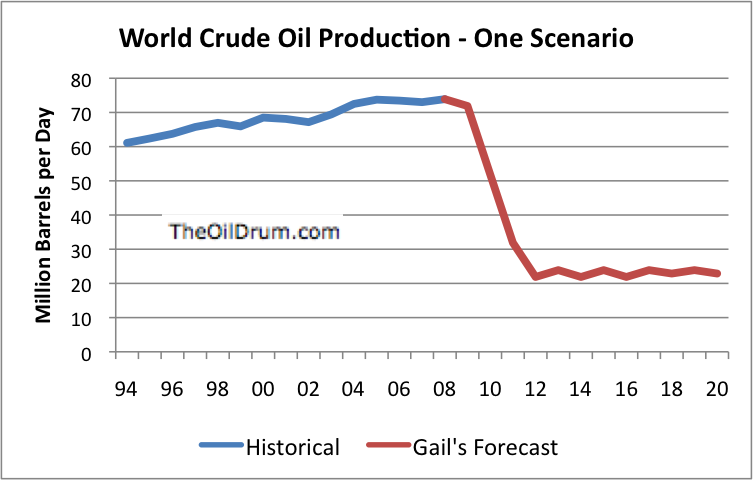

I obviously don't know precisely what would happen to world crude oil production if the world's financial system crashes, but here is one possibility:

Hubbert's curve gives us an idea of what maximum oil production might be, given geologic constraints. My forecast is more at the opposite end of the range--what the worst case might look like, if the current debt unwind results in a major world-wide financial collapse. It is impossible to assign a probability to this type of event happening, but even if the probability is very low--say 1%--it would affect planning models that consider a range of outcomes.

Background

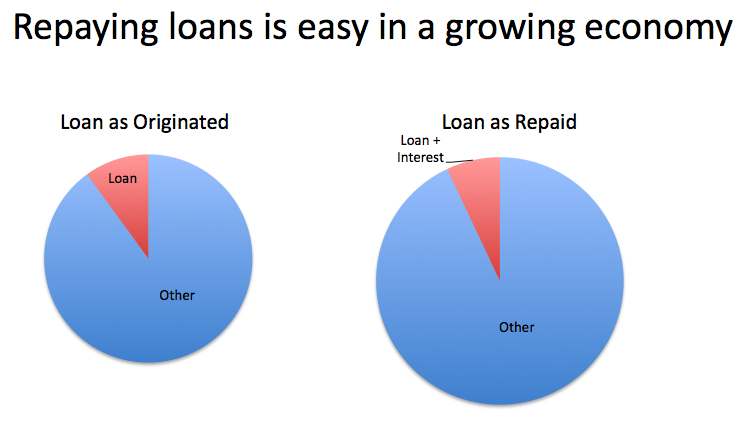

Our financial system is debt based. Since 1971, the financial system has no tie to gold or any other physical standard. Instead, in our fractional reserve banking system, money is formed through the issuance of debt. The more debt that is issued, the more money there is, and the more demand there is for goods and services. As long as the system is growing, the system works well, because paying back debts with interest does not put too great a strain on the system.

When the economic system is growing, it is possible to pay back debt with interest, because even after paying interest, there is enough money left for other things. For a business or government rolling over debt, cash flow continues to increase.

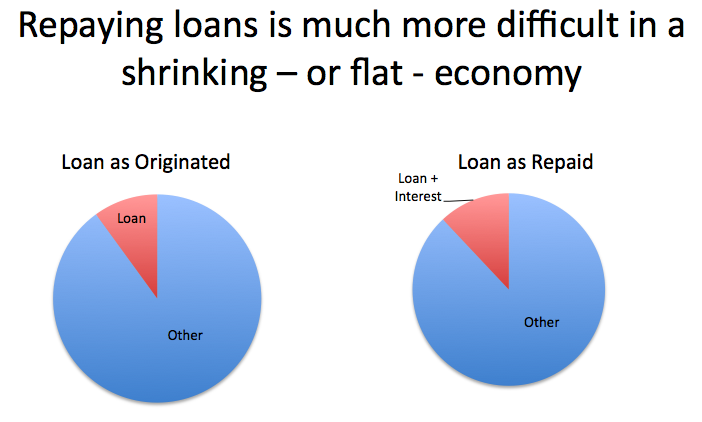

When the economy hits limits, such as an oil supply that cannot grow fast enough to support the growth needed to keep the treadmill going, repaying the debt with interest becomes a huge burden. We have been reaching that point in the last few years, as oil production remained approximately flat and oil prices rose. Food prices rose as well, but real wages did not rise fast enough to keep the treadmill going. Soon defaults on debts started.

Once defaults started on debts, we suddenly shifted into a new cycle:

Peak oil -> higher oil prices, but little additional production-> stagnant wages -> defaults on debt -> banks not in a position to lend as much because of losses on loans -> debt harder to obtain -> lower demand -> lower prices on oil -> layoffs and less investment.

If it were only the oil industry with problems, one would think the problem would be self correcting, since less investment should lead to less production, and eventually prices would go back up, and at least part of the cycle would be fixed.

The problems caused by peak oil and resource limits are much more widespread than just with respect to oil. Besides the above cycle, we also have a more general cycle:

Peak oil -> higher oil prices, but little additional production-> stagnant wages -> little discretionary income -> cutbacks in buying many discretionary items -> layoffs (restaurants, newspapers, many businesses)-> more loan defaults -> banks not in a position to lend as much because of losses on loans -> debt harder to obtain -> lower demand -> lower prices on other commodities, like food -> more defaults and layoffs -> banks in even worse shape -> etc.

These cycles are leading to a huge unwind of debt that has barely begun. There are also a large number of derivative contracts outstanding, and some of these may generate huge payments (as has already happened at AIG). These also have barely begun to unwind.

It is not too hard to envision a situation where the worldwide banking system collapses, and it is necessary to start over, perhaps almost from scratch, with new currencies and new international treaties. As the result of such changes, there is at least the possibility that the world's financial system may function at only a minimal level, and world oil production will take place at only a very low level.

Some Thoughts on What May be Ahead

At this time, there is vastly more debt than there are assets to pay back the debts. Many times, two or three or four people or organizations think they have claims on the same assets. Think of a house. An investor buys the house, and rents it out. The renter pays his rent, and has a claim on the house. The investor is the "owner", so he has a claim on the place. The mortgage on the property is likely added to a package of other mortgages, and sliced and diced and resold to other investors. Each of them indirectly believes that they have some sort of claim to the property. There also may be an insurer guaranteeing the debt that also has some type of claim. The Federal government, through one of its loan or debt guarantee programs may also depend on the underlying assets. In addition, if the owner doesn't pay his taxes, the local government may also feel it has a claim to the property.

With all of the debt defaults, and the inability to settle all of the debts equitably, some sort of debt jubilee may be necessary. This may start with some small countries, like Iceland and perhaps the Ukraine defaulting on their debts. Gradually more and more countries will default, and their currencies will sink lower and lower.

After a certain point, it may become clear that virtually every economy in the world is in this mess together. There will be no way that more debt can be issued as "stimulus" to get the world out of this problem. The only thing that can be done is to start canceling debt, in some sort of debt jubilee, and to start over.

The problem with a debt jubilee is that there would be many too many claimants for many of the world's assets. If a wind turbine owner's debt is cancelled through a debt jubilee, who then "owns" the turbine--the original owner, or the lender whose debt was cancelled? If the debt of a factory making replacement parts for a wind turbine is cancelled, who runs the factory--the original owner of the factory, or the investor whose debt was cancelled?

The debts that are cancelled are likely to cross country borders, making for international disputes. Furthermore, countries may want to retaliate for a loss of one of their overseas investments by grabbing a business located in its own country that has overseas owners. In not very long, relationships among countries are likely to sink to deteriorate, and international trade will be at much lower levels than in the past. War may even break out, or border disputes.

"Demand" will be at new low levels, because there is likely to be very little cross-border trade, except with a few trusted partners. Without this trade, it will not be possible to manufacture goods, other than those using only local products. In this kind of scenario, prices (to the extent the monetary system continues to function) would continue to be very low, because of the low demand. (A factory that is not operating doesn't need raw materials!)

The credit market would be close to non-existent, because creditors will expect that any debt that is issued could easily be cancelled. New investment would be limited to what can be financed by cash flow. With low prices, this cash flow would be very low, further limiting investment.

It is possible that in some parts of the world, the monetary system will cease to function all together, and barter would become necessary. Because barter is so cumbersome, this is likely to have a further limiting impact on trade.

In such a scenario, I would expect that oil production would be significantly lower than the physical resource available. If nothing else, it will be difficult for the whole chain from local production to pipeline to refinery to distribution pipeline to consumer to function properly. Countries that previously exported oil overseas will see that their chances of getting paid are less than 100%, and may reduce their production to match what they can sell through arrangements with trusted parties.

Production of many other goods may decline as well, as the lack of an adequately functioning monetary system limits the ability of long supply lines to function properly. Natural gas and coal production may decline, as well as oil production. Food through mechanized farming may decline, as Liebig's Law of the Minimum makes itself known.

On Figure 2, I show only a slight decline in production in 2009, but then large decreases in 2010, 2011, and 2012 to a level not much above 20 million barrels a day. If it reaches such a low level, due to a widespread failure of the financial system, I would expect electricity to be affected in many locations, and because of electricity, water and sewer systems. Some large cities may become uninhabitable.

Under such a scenario, I expect all of this would take a while to get sorted out. If there is a widespread failure of the monetary system, it is possible that many governments would be replaced. Some countries may fall to pieces, in the manner of the Soviet Union after its collapse in 1991. Governments may not have much faith in other governments--except perhaps with a few trusted trade /strategic partners. New monetary systems will likely be put in place, but many will not be any better than the previous ones, so bubbles and further collapses may occur.

In such an environment, international businesses will find it virtually impossible to survive. Businesses are likely become much smaller and more local. As I have shown on Figure 2, it may be many years before oil production begins to rise again. In fact, it may never rise again, if international trade stays at a low level.

I would expect that the renaissance, when it comes, would begin with basic human needs, in local communities and local agriculture. People will grow their own food, and trade with others in their community. There will be small shops that make shoes and clothing and cooking utensils. People may begin to raise animals for transportation.

People will still need energy for heating their homes and for cooking. The initial impulse will be to cut down trees for these purposes, but with the world's large population, this will tend to produce deforestation. Neo-environmentalists may urge people to use other products for this purpose--such as coal or oil, if these can be obtained. There may be some local electricity produced, particularly water generated, if transmission systems can be kept in good enough repair.

If this scenario happens, it is difficult for me to see much of a future for large complex systems that require specialized parts from around the world. Thus, I would expect large wind turbines to fall into disrepair in a few years, and solar PV panels to be very difficult to obtain, after such a crash scenario. Smaller windmills, similar to what a person sees on old farms, may come back into popular use, as may coal operated steam engines (at least in the US, where coal is still plentiful).

If you have been following the interconnected threads of what is occurring in our system, you are aware that the above scenario is at least a possibility. Due to the complexities involved, it is impossible to estimate a percentage likelihood of this particular trajectory, but the odds are increasing of something like it.

If such a scenario should happen, it could result in our world becoming a very different place in a very short time. If the odds of this happening are more than very slight, what should our response be? Should we be devoting all of our efforts towards avoiding this scenario, or allocating some resources towards adapting to it?

I want to thank Nate for his assistance on this post.

I also circulated my Figure 2 graph to Oil Drum staff earlier, and got some feedback from them on the subject. I am sure that if a survey were done among Oil Drum staff, there would be a wide range of opinions on the likelihood of a scenario such as I show, with some believing the probability to be 0.00%.

This is one fundamental flaw in economics - it parses stochastic events, (with imperfect information) at their mean, and doesn't remotely give appropriate signals for shortfall scenarios. (See Taleb). It is clear that there is less oil available for the future than there was a year ago, yet prices are 1/3 of what they were, so we know that the market prices at the marginal unit balancing short term supply and demand, not anticipating the future. Economics tells us we needn't worry about future and oil and gas supplies - maybe it is right after all. Would economics/finance predict it's own demise via price signals?

Whatever the odds of Gail's above scenario are, they are higher than the below scenario, which would be some sort of globally reinforcing nuclear exchange. In my opinion this is what has to be avoided at all costs. Diplomacy right now is measured and civil. If we do have a full blown currency crisis something like the below graph would have a low but non-zero possibility.

It would have been interesting to ask oil traders, at the end of 1998, when the average 1998 spot crude oil price was $14, what the average annual oil price would be 10 years later, in 2008. In any case, in early 1999, the Economist Magazine published their $5 Oil cover story, predicting low oil prices in the $5 to $10 range for the foreseeable future.

Average Annual US Spot Prices:

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/dnav/pet/hist_chart/RWTCa.jpg

And my usual Great Depression reminder. It appears that after 1930, worldwide oil consumption rose throughout the Thirties, and here is a constant dollar (2008 dollars) oil price chart from Carpe Diem:

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_otfwl2zc6Qc/SR7wlGrkytI/AAAAAAAAHvE/aOVvsxq_fP...

My outlook for the Greater Depression is a long term accelerating decline in net oil exports versus the expanding volume of world oil supplies that we saw in the Thirties. And of course we can show actual case histories of net export crashes. Indonesia for example:

The worst imaginable scenario is World War III, but production would perhaps only be cut in half.

For a world wide financial collapse scenario look to the Former Soviet Union's experience. (Perhaps you can post the USSR production graph?)

Discretionary oil use can reduced, but essential needs will be met. People will still eat and heat their homes and buses will still run. Police, fire and utilities will still function, although in the Soviet Union they often were not paid.

World wide economic collapse is happening, but the developing economies will recover quickly because they have unexploited potential in the form of basic industry and infrastructure needs.

The diagram above shows the development of oil, natural and electricity consumption for the Russian Federation for the years 1990 through 2007. During the five years post the disintegration of the Soviet Union, oil consumption were roughly halved, natural gas consumption fell with approximately 20 % and electricity consumption with roughly 25 %.

NOTE both y-axis’s are not zero scaled.

What preliminary data now suggests is that during this financial crisis oil, natural gas and electricity consumption falls.

That was certainly true for the Russian Federation, but as noted down the thread it also resulted in a huge drop in production, contributing to a large drop in net oil exports.

That's a very optimistic "worst imaginable" nuclear world war if I ever saw one!

From Mazmascience's energy browser (based on BP data)

[Edit: deleted graph as its creator Jonathan Callahan has posted the info below]

I just wish the fools try to maintain "status-quo" until they realize they don't have enough oil for wars. I wish, things unfold like its mentioned in the Long Emergency. But I'm scared to think of what the various nations will do given their latent nuclear weapons. They don't need (much) oil for firing these, anyway.

A self-destructing pakistan is good enough to start WWIII.

Paul,

The Former Soviet Union provides an excellent example of how any analysis based solely on past production rates can fail to predict future production.

The following graphs from the Energy Export Databrowser show production and consumption histories for the Former Soviet Union and for the Russian Federation. The data come from the 2008 BP Statistical Review.

Anyone looking at the FSU time series in the mid 80's would have surmised (or calculated with Hubbert linearization) that they were on their bumpy plateau and that their production (and exports) were about to suffer a decline.

Production did in fact drop significantly starting in 1990 but it was due to political rather than geologic factors. And consumption dropped almost as fast but with a slight lag. By the year 2000, FSU exports were at the same level they were in 1980 and they were significantly higher last year.

The bottom line is that political/economic factors are hugely important and less amenable to the kind of analysis that science and engineering types are comfortable with.

Techniques like Hubbert linearization, when applied to politically stable zones like US or North Sea production, let us know the outlines of possible production. But future production, consumption and price levels, especially in periods of political and economic chaos, remain very difficult to predict.

-- Jon

The HL method gives us a plausible estimate of the area under a production rate versus time curve, i.e., URR for a region. As such, it is far more accurate at predicting cumulative production than at predicting the production rate at a specific point in time.

In the comments section on my original post on the top net oil exporters, in January, 2006, after some discussion with Khebab based on HL modeling, I concluded that Russia would probably resume its production decline within one to two years. My premise was the ongoing rebound in Russian production was largely just making up for what was not produced immediately after the fall of the Soviet Union. I outlined the theory in this article:

http://graphoilogy.blogspot.com/2007/06/in-defense-of-hubbert-linearizat...

In Defense of the Hubbert Linearization Method (June, 2007)

I should add that all of this was based on using Russian production data through about 1984 to predict future cumulative production.

I have read articles suggesting that the decline in production (due to failure to adopt new technology) may have also been a cause in the failure. I haven't really looked at the situation in the Soviet Union, but all one needs is a flattening in oil available for domestic use, or a small dip, to start cause widespread debt defaults, and to begin a downward cascade.

Okay, I'm a little confused by this. What would have been analogous to "widespread debt defaults" in the Soviets' Marxist system?

Good question.

Simple answer:

____________________________

Widespread default of your Comrades' Promises.

The "promise" is a fundamental element (think H in periodic table) in all economic systems.

I do X for you to today in exchange for your "promise"

to do Y for me tomorrow,

where value of doing X today (as far as I'm concerned) =< value of getting Y tomorrow (as far as I'm concerned)

AND where I "trust" you to live up to your promise.

-----------------------------------------

Now in a capitalist system, "the promise" (basic element) is replaced by money (a complex compound) and the equation becomes something like this:

I do X for you to today in exchange for Money's "promise" (M amount of Money)

to do Y for me tomorrow,

where value of doing X today (as far as I'm concerned) =< value of getting Y tomorrow (as far as I'm concerned) based on having M amount of Money then,

AND where I "trust" society to live up to its promise that it will give me Y tomorrow in exchange for the M amount of Money I receive today.

---------------------------------------

You can see where this is going by substituting for Y, my expectation to receive Z barrels of oil for that M amount of Money I received today and where society is no longer able to deliver on its implied "promise".

When society can no longer deliver on its promises (be they capitalist money promises or commie comrade's promise to give to each according to his needs) you have default.

That is a good point. Even in this country, a lot of the promises that are going to be defaulted on are the implied promises that have been made. States have all kinds of programs - schools, universities, roads, medicaid, unemployment insurance. In the months and years ahead, states are going to find themselves unable to fund all of these promises.

The federal government has also made promises: Social Security; Medicare; war in Iraq and Afghanistan; keeping banks from failing; pay back its loans; money will hold its value.

It is pretty clear that not all of these promises can be honored. So far, there have not been major defaults on any of them, but they will be coming, as the amount of resources available decline.

That's the point Nate Hagens has been hammering, that we depend on real capital resources and that money is only a marker. Money doesn't even specify who owns the resources, but only the promise - the alleged promise. In a declining musical chair economy where there is more money than real resources, continual default will be the rule until that "excess money" collapses in debt and default. This implies to me a "flight to real resources" - not to cash, but to wheelbarrows, chainsaws and chainsaw parts.

cfm in Gray, ME

Paul Krugman in today's New York Times has an editorial that hammers in the point about folk not being able to live up to their "promises".

In this case he's talking about AIG, the insurance company that "promised" to cover the defaults of defaulting bankers but then itself turned into a "zombie" institution.

The insurance game is the ultimate in the making of promises, because they don't have to perform until after it is too late, and then what are you going to do about it? Sue them? Sue their ghosts?

But, but, but ... I've got it all here on paper, in the, in the contract. It says pigs "must" fly.

Some may wonder why "Gail the Actuary" would get into the oil business. Actuaries work in the insurance business and make all kinds of forecasts about claim experience, investment income, and most anything else that goes into insurance company operations. It was pretty clear from my early reading and thinking about the situation that peak oil would wipe out the financial system and with it the insurance system.

Insurance companies collect premiums, invest the proceeds until it becomes time to pay claims or benefits, and then pay out the claims or benefits. If everyone else is losing money on their investments, insurance companies are likely to lose money as well. Some actuaries work with pension plans, and the idea is the same --collect funding, invest it for a period or time, and then pay out benefits. Same problem.

Life insurance companies seem to be getting into trouble already because they promised more (on annuities and other products) than investments in real life are going to deliver.

Pension plans are likely already getting into trouble, but they can often hide the situation for a while. As I understand it, there is some flexibility in when a pension plan recognizes an investment downturn. Their payments are very long term in nature, so they likely have enough cash on hand for now, even if their investments aren't doing well.

Property casualty insurers (workers compensation, auto, homeowners, medical malpractice, etc) are doing a little better. They tend to invest in high-grade bonds, with much less exposure to stocks. Insurance regulations allow P/C companies to carry the bonds at amortized value on their books, unless there is a clear problem with the bond. With this accounting, unless there is really a default, the companies' financial statements still look reasonably OK. Also, if there is less driving, auto claims are likely down. I would expect homeowners' experience to get worse, with all of the vacant houses sitting around.

Gail, interesting perspective. Thanks.

I guess actuaries use a slightly different language. They don't call it a "promise" but rather a prediction or an actuarial projection with an assigned confidence level. But its all kind of the same thing. We are each trusting that somebody else in society will live up their end of what we believe they promised.

A key to understanding what happened to the USSR and their oil production is that oil prices crashed in the mid 1980's from the high levels of the 1970's and USSR lost its main source of external income. With low oil prices there was no incentive to invest in or even maintain their oil industry, nor was there money to pay for imports or their military, police, etc.

No doubt some of this is taking place today, not just with oil but also with mining and manufacturing.

I used to think that an economic collapse leading to social disintegration was something that was unlikely to happen, at least in my lifetime; however, when I read accounts of USSR and Argentina I see that it clearly is possibe.

We are living in dangerous times.

The Energy Export Databrowser allows you to convert to monetary units of constant US dollars (inflation adjusted to 2007). For the Former Soviet Untion this tells a particularly interesting story.

Just as Soviet exports were increasing during the 1970's:

the price spikes due to the 1973 Arab Oil Embargo and the 1979 Iranian Revolution brought hitherto untold riches to the USSR:

(Before this year, a billion dollars a day was considered a lot of money.)

What had been an economically tottering system was kept alive throughout the 1970's. By 1980 they were swimming in new money from the outside.

However, the price spikes of the 70's led to economic contraction and conservation in the West as well as new production in OECD friendly areas like the North Sea, Canada and Mexico. (Check the databrowser yourself.)

Together these brought the price back down to where the USSR had to rely on its own internal economy which, by that point, was no longer sustainable.

Then came the collapse.

True, this is an overly simplified story overly focussed on the economic rather than the human dimension. But I believe it is at least a large component of what the history

booksblogs will eventually say.-- Jon

Russia had the advantage of the rest of the world being in good shape, and an economy that in many respects continued to function (people had homes, public transportation, their own gardens). I think it is a better situation than we could hope for here.

The most troubling feature of the FSU collapse was the lack of law and order that Dmitri Orlov told of in "Reinventing Collapse".

I remember in 1996 being on a business trip to Norway, just across the border from St. Petersburg. When I told my hosts that I wanted to go to St. Petersburg they where emphatic that I not do so and that I would most certainly be mugged and possibly killed, as several people they knew had.

Uh, perhaps you meant Finland, not Norway?

You are correct, I was in Karhula, Finland.

Paul-the-Engineer "World wide economic collapse is happening, but the developing economies will recover quickly because they have unexploited potential in the form of basic industry and infrastructure needs".

Could you expand more on this line of thinking? I am living in a developing country in Asia.

I disagree with your assessment and my background includes many years of work with nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons, along with the forecasting and scenarios associated with them. A full scale nuclear war could cut oil and gas production by far more than half depending on targeting choices, strategic goals pursued, and weapon configurations used.

The USSR was held up from the full impact of collapse by the surrounding nations. A global collapse that effects everyone has no one left to hold the rest up.

I suggest that your scenario is excessively optimistic, especially for one involving the exchange of several thousand strategic warheads.

Hello Greyzone,

I would also imagine the nuke targets would include the P & K mines and processing facilities, the H-B natgas into ammonia & urea factories, plus the huge sulfur stockpiles. In short, ICBM-targeting existing I-NPKS infrastructure would guarantee full-on O-NPK recycling for any survivors!

"Diplomacy right now is measured and civil."

This is not universally the case even among "civilised" countries. e.g. Israel and the Palestinians.

the old turkey farm thing eh...

what gets me in hindsight is how strong the correlation is between peak and the melt down of wall street was. Lehmans bros is right on the nose.. why should it be so tight i don't know, I always thought the lags in the system would take way longer to play out and be more hidden. PO turned out to be an actual event.

odd that

The role of complex networked systems currently under threat is indeed vital, as is the recognition that a credit bubble creates excess claims to underlying real wealth. In contrast to currency inflation, which merely carves the real wealth pie into ever smaller pieces, credit expansion creates multiple and mutually exclusive claims to the same pieces of pie. Everyone feels wealthy, but that wealth is largely illusory. Once an inherently self-limiting credit expansion can proceed no further, it implodes, and excess claims are extinguished. This is the deleveraging we are currently seeing worldwide.

The effect of the on-going destruction of credit, which constitutes in excess of 90% of the effective money supply, will cause a global crisis of epic proportions. Money is the lubricant in the economic engine, and with an insufficient supply of it, the economy will seize up as it did in the 1930s.

For my take on the interaction between energy and finance, see Energy, Finance and Hegemonic Power.

Agreed! You say it very well.

Good thing you agree as her view contradicts yours.

You posit that "when the economy hits limits, such as an oil supply that cannot grow fast enough to support the growth needed to keep the treadmill going, repaying the debt with interest becomes a huge burden." And you argue from this that the current financial crises is a consequence of crisis in oil supply.

Stoneleigh argues that "once an inherently self-limiting credit expansion can proceed no further, it implodes, and excess claims are extinguished. This is the deleveraging we are currently seeing worldwide."

No mention of oil supply as a factor. You need to decide what you think is true and stop confusing yourself.

Here's are a couple of articles expanding on my view, which is essentially that credit bubbles have their own internal dynamics that are far older than the fossil fuel era. They are thoroughly grounded in human nature. I would argue that energy subsidy has driven this one to unprecedented heights, and a lack of energy will be a very significant factor in the severity of its aftermath, but I do not believe that lack of energy is a proximate cause of the great deleveraging.

On the nature of credit bubbles: From the Top of the Great Pyramid

On the fate of credit bubbles: Inflation Deflated

On the genesis of this particular credit bubble: The Resurgence of Risk - A Primer on the Developing Credit Crunch (August 2007)

I thought it was interesting that in the paper This Time is Different: A Panoramic View of Eight Centuries of Financial Crises, the authors Carmen M. Reinhart, University of Maryland and NBER and Kenneth S. Rogoff, Harvard University and NBER found makes this observation (page 15):

The authors of the aforementioned study did not make the connection to fossil fuels either. I would argue that fossil fuels have allowed the US growth bubble, and in fact the current world growth bubble to go one much longer than would be the case without fossil fuels. Once the fossil fuels, and particularly oil, growth stops, the ability to keep the economy expanding stops, and the defaults become much more likely.

The authors of the paper didn't see that connection, but if one thinks about the situation from a cash flow point of view, it is all too clear. Without growth, interest takes too big a bite out of future cash flow, and defaults become inevitable.

So then. if I understand correctly, without having read all these links (though I would love to, sometime soon...), Stoneleigh and Gail are saying that there were credit bubbles, which we have had previously, that got perhaps even bigger than they might have, facilitated by cheap oil, that would have popped anyway, but Peak Oil made that additionally inevitable, and is making the recovery unlikely. So this time, it will be different.

From a bird's eye view - it is sometimes comical that we humans seem to require a perfect 'explanation' for the causal events that brought us to this moment, almost so we can sigh 'ahhhh' and feel content about it, instead of just looking at the facts of this precise moment and what are we going to do about it. Some pervasive blindspot in our wiring perhaps.

Hey, I can't help it - I used to be an academic ;)

Seriously though, having a good model helps when it comes to having a view of where one is going and therefore how much preparation is required. If you look at the credit bubble as a Ponzi scheme, albeit an unintentional one, then it sheds light on why government bailouts will be ineffective, and leads one to prepare for a much deeper collapse than might other wise be the case.

Rest assured that anthropogenic "collapse" will be at least as deep and broad as the end-Cretaceous event. The extinction of vertebrates much larger than a rat is virtually certain. How does one "prepare" for such a thing? What distinction can be made between adequate & inadequate preparation? Do you really think that financial bubbles & Ponzi schemes & government bailouts are even relevant to the situation we or our children face? Could it be that fascination with such things serves as an avoidance mechanism, distracting attention from the gravity of the real issues - which are ecological & biogeochemical, not cultural or sociopolitical at all?

Damn straight. A certain paralyzing effect, deer in head lights feeling but the train is so seemingly large that I will just watch it come but staying in the middle of the tracks to insure that when it does come the blow will be effective. No reason to be maimed and if it is a large collapse only luck with the preparations in place will "save" me and those that adapt to the new paradigm.

Ron,

Whilst I agree with your somewhat sobering conclusions about where the future is heading, collapse is likely to follow a number of distinct phases the first being economic collapse and if attempted survival is our goal then a deep understanding of each stage is required. I’m thinking along the lines of:

(1) Transfering wealth to the most stable currency. Norweigian Kronas anybody?

(2) Exchanging currency for presious metals. Whilst there is still a functioning economy.

(3) Exchanging presious metals for beans & bullets. Tthe final barter stage.

Of course survival in the face of population overshoot will as much a matter of luck as preperation & nature will be playing with loaded dice.

Of course we feel content (and sigh 'Ahhhh' about it).

It validates our inner predictive models.

We rely on our inner predictive models for survival. Validation of the model --with a good sounding story-- implies increased likelihood of survival. That makes one say, 'Ahhhh'. Evolution would have it no other way.

Stoneleigh and Gail, I'm not so sure there isn't another way for things to play out. Debt can be repudiated, cancelled, written off or whatever you call it, but it can also be inflated away. "Quantitative easing", i.e. printing money seems to be the answer they are coming up with. Yes, credit collapse can eat up a lot of this, but at a certain point inflation, severe inflation may break out in some commodities, e.g. food and energy. I'm not sure food inflation isn't taking hold now.

I certainly don't dispute collapse, but I think it can happen more than one way. Inflation allows some debts to be paid off, and TPTB (try to) protect themselves by accumulating hard assets like land, energy, farms, etc. The mountain of debt is huge and can never be repaid, that's for sure. But there are two ways out, not just one.

There is ultimately a floor, not everything goes to zero. Now it is extremely unlikely that we'll reach the floor without massive chaos, so it could be purely hypothetical floor. What is for sure is that the middle class as we know it is going, going, gone here and around the globe.

There remains a distinction between money and credit: money doesn't have to be paid back, even in principle. You can hand it out, and they are handing it out, and they will destroy the currency. You can exchange money, but how much of what you can exchange it for is completely outside of any contract.

I also have a problem with attributing everything problematic to complex, networked systems. Our bodies are complex networked systems, as is the web of life on the planet. It doesn't improve things to cut off fingers or simplify the biota by killing off species. But this is a whole other issue to debate -- not now.

I personally resent complexity, being a pure mathematician by early training -- it's only very late in life that I've come to accept both its reality and necessity, but like I said -- not now.

Of course, I do agree that we do face a drastic simplification as the underground resources become less and less accessible. But that's simply because the resource base for the complexity will no longer support as much complexity. The moon is simple for that reason, sort of. But, like I said -- not now.

And ...

It is possible the collapse will come through widespread hyperinflation. Not only will it do away with current debt, it is likely to put an end to future borrowing. It seems like trading with other countries will not work very well either. We still end up with the system not working, and the economic system likely collapsing at some point.

Hyperinflation? Not any time soon.

I don't think it's necessary to figure out how exactly Americans are going to go broke. Most will get there the old- fashioned way, they'll lose their jobs. No jobs, no money. No money, no borrowing. No borrowing, no spending. No spending and the businesses that depend on spending fail. The circle is closed when these businesses fire their workers.

Any debt held by any of the above is more or less uncollectible. Bankruptcy clears the accounts.

Here are foreclosures:

Here are personal bankruptcies:

Unemployment:

If anyone thinks demand is going to pick up anytime soon, they are totally insane. Few are creditworthy and those that are treat credit like it is a contageous disease.

Inflation takes place/causes and is caused by credit expansion. A 'virtuous' cycle causes GDP to expand. This is what the government and the Fed are trying to revive.

Hyperinflation takes place when money velocity increases and GDP declines. It might happen yet, but money velocity is in the toilet:

You can get the sense that available cash to fuel demand is falling faster than the depletion rates for just about everything else. No 'Mon' no 'Fun'.

Soon, probably not -- I agree. But the basis is being laid for it. Productive capacity is being destroyed by a host of factors, disinvestment for one, and it will hit certain sectors first. There is part of the food demand that will not be readily given up, or given up only after everything else is. I think inflation is not dead there yet, nor will it be. Amazingly enough, the MTA in NY is preparing to raise fares and cutting service! Local taxes are certainly rising. There is deflation in many commodities, especially discretionary items, and there is certainly asset deflation (housing, real estate, etc.)

I haven't researched it yet, but was this true of the Weimar Republic?

I agree, the groundwork is there for hyperinflation in the future, after a long - and confidence crushing - episode of deflation. Deflation is customers getting out of assets and into cash money (not credit). When assets are priced @ zero, and the people uncertain whether the cash money will be next to lose value, the mad stampede to get back into some other asset or some other currency will begin. This stampede is the hyperinflation.

Hyperinflation is usually the result of war or defeat or a government under siege. A long depression could trigger it.

Ordinary inflation is a large (if not the largest) component of what we Americans call, 'growth'. The supply of money in circulation increases - in this case by increased 'fractional lending' by banks as well as the increasing numbers of transcations taking place repeatedly with that borrowed money. Some money is held as profits but a large part of the surplus of credit is captured or sunk into all the different goods and services.

A car might cost $25,000; $3,000 of that might represent the materials and the actual hourly and management time and effort spent to build and sell the car ... the rest is debt that has been assigned against the car and must be recaptured by its sale: the factory which was built with borrowed money, the equipment built with borrowed money, the mortgages and credit cards of the workers that have to be serviced by their wages, the loans to suppliers, dealers, transporters, etc. etc. etc.

Just like there is 'sunk energy' (usually in the form of burned hydroarbons) in every service and good sold, there is 'Sunk Debt' in the same products. This debt is responsible for the increase in price; petroleum is responsible for production effiencies which reduce costs; the sunk credit has the effect of increasing costs. The higher prices of goods include the debt incurred by their making; this isn't a problem since the same credit conditions increase the purchasing power of consumers of the goods. The pie - both supply and demand - gets larger and larger.

There are perceived benefits to inflation all around. A low, equilibrium level of inflation is unnoticeable; that rate will cancel out the interest or borrowing cost while reducing the value of the principal over time; these are the benefits to borrowers. The government gains the benefit of an invisible tax that cannot be evaded, a taz that ironically increases the government's economic leverage by its exercise. The lenders gain transactional benefits they would not have otherwise; inflation creates customers that would otherwise not exist. This is why a desperately poor, third world country, China, lends the USA and its wealty citizens money - it's vender financing. Even if they 'lose' by lending, they gain in profits on the sales themselves.

Hyperinflation is different; the money supply expands but - there is no equilibrium, the pricing cycle increases and becomes self- reinforcing.

This is a good explanation of hyperinflation.

Another, more technical explanation is here.

:)

I would add that even with inflation, the lenders have to have the impression that they are getting more back in interest than the inflation rate--that is, that the "real" interest rate is greater than 0%.

Steve,

Thanks for the nice charts!

I agree that deflation is our problem today, and it is hard to see a way around it.

I don't think hyperinflation will save the day either, assuming the government could figure out a way to get there.

The counter-point to a deflationary boom, of the kind that we enjoyed in the late 1990's, is an inflationary bust.

Standard recessions tend to be disinflationary because spare capacity grows and demand falls but each of these occur outside of a catastrophic framework. Production shuts down more slowly, and more reluctantly. Credit carries onward, and the anchors of the banking system remain intact. Much of the work done in a standard recession is preparation for recovery. Much of that work is intentional.

In a collapse of the kind we are experiencing now, however, the future is canceled as the system both behaviorally and structurally can no longer make plans for it. Production is closed immediately. Labor is let go at an uber-fast rate. The collapse has started out in textbook fashion with a demand crash, and the result has been what I call a petite deflation. The petite deflation feels strong, because of the rate of change. However, I expect it to be short in duration.

While I don't "expect" it with certitude, I would say the highest risk now is that we move next into the heart of this bust--which will be an inflationary depression. In its nastiest form, it won't matter one whit that entrepreneurs want to raise more cattle when beef prices skyrocket, pump more oil when goo goes back up, deliver more fruit when juice demand rises, or innovate. When the future's been canceled there will be no credit for any of these business propositions and lenders will say "I don't care that X is rising and that your plan to more efficiently deliver X looks profitable now."

This monster of a crisis is unfolding much faster than other debt-deflations. I anticipate we are already in the last stages of the petite deflation which started in July 2008. My view now is of an inflationary depression brought about first by the destruction of credit, and then a destruction of money, that will run roughly from July 2008 to say July 2011. The first 9 months of that 3 year period being felt as "deflation" with reflation coming next, and they eventually strong inflation and then hyper-inflation.

The return of inflation this time will be a marriage of the cascading shuttering of productive capacity (which leads to the current de-stocking) and then the destruction of money/government bonds as faith in governments fall in the midst of gargantuan government bond supply. While it's true that velocity of money is dead, it's also true that all the hoarded capital in government bond markets will be called upon to live (consumption), just as capital in equity markets will be called up on for consumption. For those who think there's an unstoppable deflationary trend that is set to run here for several years, well, it just can't. If it does not run into my inflationary depression first, it will run into war.

Deflationary depression is not sustainable as a long, chronic condition.

Best,

G

Dave, I absolutely agree that inflation is an alternative over the long haul, and I think that was the thought of the previous administration. Perhaps that was the reason for a weak candidate running against Obama, and after a round of unbelievable inflation, the thought was then to try to get repubs back into power. If the dollar loses 30% of its value and then we have some semblance of a recovery, the debt may well be reduced, mathmatically, to a reasonable % of GDP. If our government could be convinced to exercise fiscal restraint, even austerity, there could be an end game with nonviolent consequences. That, however, will also require the same kind(s) of measures across the globe. The chance of that are slim to none.

Nate, I would like to think that the "worst case" prediction to reflect something in the neighborhood of say 3-5 MMBO/D worldwide. Some isolated pockets will continue to produce, even in the case of war. Not all production will require all of the nicities we have today, like transportation, gathering, pipelines, etc. and many wells can be produced with gas engines vs. electric. The oil industry was once only local, and could be again, and could be more efficient. If I had to construct a micro refinery, I think I could, although it would not produce sophisticated products, and I could sell everything locally, except maybe the cosmetic grade parafins. Thus, my otherwise meaningless production could continue, along with countless others. I know, that is effectively zero production, but should be accounted for in some small way.

Thank you Gail! As always a clear and thought provoking article.

I am certainly with you in thinking that the chances of such a scenario are more than 0%. Indeed, it may be much more than that.

I'm especially interested in jubilee as a means of correcting some of the problems with our current economic system. For jubilee to work, a few things need to happen;

1) It needs to be explicitly a one shot deal

2) It has to remove all lenders claims on the debtor, not just the debt.

3) It has to be the prerequisite to significant limitations on the creation of debt post jubilee.

This last item is critical. Our economic system as developed into a bizarre twisted system where debt equals wealth. This must come to an end.

There is a decent blog site dedicated to jubilee that is worth checking out for anyone interested in the idea.

http://cancelourdebt.blogspot.com/

The good news is that I personally don't think that lower wages (the real cause of the current crash) were caused by peak oil, but rather by policy choices to change income distribution. If we can solve that item (admittedly a big if, but a question of macro economic policies, not a physical impossibility) then your scenario becomes more remote.

Otherwise, as I wrote to you, your scenario is both pessimistic (fast decline) and very optimistic (quick stabilisation thereafter)...

Choices to change income distribution are certainly part of the problem. It seems to me that these choices are very much tied to a world view that a few large corporations, and a few top people at these corporations, can control a large portion of the wealth. This can only happen in a debt based system, which is dependent on growth.

If one goes to a less debt dependent system, we are likely to have a world where the smaller players are more valued, and thus receive a larger share of the wealth.

Interesting you bring this up. When I was in Indonesia I realized there are really two monetary cycles or flows.

The first flow we could call the primitive flow. Farmer->crops->worker->farmer->>>

I simplified it but basically all the money circulates within the local economy it never becomes concentrated its simply passed around in a fairly small circle paying for local goods and services.

A bit larger but similar is regional trade using regionally local goods.

On top of this we have layered our global trade and mega corporations this is a quite different form of trade in the sense that on a fraction of the money goes back into the local economy in the form of wages the rest is concentrated in the hands of the wealthy scattered all over the world.

The key for the ability to concentrate wealth is not even in the means of manufacture but control of ownership and economies of scale. The problem of course is that it has basically no mechanism to recycle the wealth instead for all intents and purposes the wealth is effectively destroyed at the top as its converted into ever larger ownership slices or over priced luxury goods. A large part of the wealth at the top is thus concentrated into taking control of ever larger slices of the means of production. Periodically of course these companies perform poorly or loose money and the wealth is simply destroyed. Obviously a lot of it went into ever more aggressive leveraging and we are losing vast amounts of this sort of wealth as our global economy contracts.

In the ends it becomes obvious to me that the problem is our economy is very efficient at generating the means to concentrate wealth but very inefficient at redistributing this concentrated wealth so that the poorer classes can actually buy the produced goods. This was hidden till recently by the use of consumer debt in the western countries thus China and India produced a myriad of goods that their own populations could not afford and these goods where exchanged for debt.

Despite the immense wealth of the global corporations it seems to me at least that they are intrinsically unstable the cycle becomes to extended and the wealth can no longer flow back towards the poor. Effectively no matter how hard they labor they can no longer accumulate any wealth and eventually more and more can no longer service the debt loads they take on in exchange for their weekly paychecks.

In fact we can look back into the past at companies such as the Dutch East India Company.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_East_India_Company

Just reading the history of this country should cause you to realize we have almost exactly the same problems today.

These large multi-national corporations that in the end depend on effective slavery eventually fail because in my opinion they subvert the natural flow of wealth and deprive producers of their returns. With many things their seems to be intrinsic limits and economies has to become circular or eventually they fail. The real rate of accumulation of wealth is actually very small say 0.1% or 1% or something like that. I wish I could fined older texts and determine the real rate of wealth accumulation say while Rome was a republic I suspect that wealth concentration was a very slow long process.

You make some good points. The bigger the company, the easier to divert money to the top of the pyramid, and the less likely income will get back to those producing the goods. Oil and fossil fuels have enabled these huge companies, both directly (transportation) and indirectly, through permitting the economy to grow rapidly enough to support a lot of debt.

Very good point about cheap transportation.

The original mega corps first trans-continental shipping empires then canals and railroads where critical to forming the first mega-corps additional ones where leverage on top of these transportation networks. Sears for example.

This suggest that once cheap transportation disappears the mega-corp will crumble.

This also suggest that most middle class jobs are probably not long for this world since few large corporations will survive.

In my own area telecommunications.

Offhand I'd guess that computer chip manufactures because of the expense of the facilites would survive ( at least technically ). Board manufactures and assembly may move regionally.

So I could see expensive components esp small volume ones continue to move but stuff thats easier to make probably will move to local manufacture. Drugs are another area which probably will continue to have large corporations involved.

Paradoxically I'd not be surprised to see lower value goods that are regionally scarce but stable continue to be shipped. Things like grain and wood and of course oil. A lot of this could move to cheaper sail based transport.

Regardless trade will happen for good reasons not simply because of wage arbitrage and of course as the middle class collapses the global wage differential will also collapse along with economies of scale.

Yet again expensive oil practically seal the fate of our current system as they are forced into collapse.

This bring you back to the case that we seem to have hit peak oil and peak debt at the same time. Even though its really hard to prove the combination it just can't be a coincidence.

For me at least this just confirms that our final collapse must take place in a expensive energy regime. As long as cheap energy remains available we can struggle along. This does not mean we won't see a depression level economy even with cheap oil as Nate often points out but it does mean real collapse is not imminent. Expensive energy is a critical part of collapsing the large corporations and thus most of our complex global trade and associated mega corps.

Depends on what you mean by 'imminent.' Not a day goes by I wish something had clicked for me back in 2005 when someone gave me a peak oil presentation but for whatever reason I just sailed into the night afterward thinking, "Well, that was certainly interesting." Then I forgot completely about it until 2007 when I started to investigate the likely impacts of oil depletion on CO2 emissions. My everyday experience now is that it is imminent.

But moving emotions out of the way for the moment and assuming some degree of steady degradation, when are the rich countries of the world more like what we now call third-world countries?

a) starting now, very clear by 2011

b) starting now, very clear by 2013

c) starting now, very clear by 2015

Not tomorrow, to be sure. But then there is that whole Black Swan catastrophic collapse event that could happen at any moment...

I think Jerome has it backwards. Income distribution changed because of resource limits. The petri dish was filling up, and that dried up the wealth that was flowing to the middle levels of the pyramid.

Don't forget the thousands (millions?) of "super-commuters" who drove until they qualified for their 3000 sq ft balloon frame insta-houses. Their commutes became a lot less super at $4+ per gallon, and drained a bit of wealth off these would-be exurban barons. Suburban land values are inversely related to commuting costs. It was fun while it lasted.

Good point!

"It was fun while it lasted."

No it wasn't.

I am reading "Deep Economy" right now. The most interesting thing about it is he shows that not only was the exurban/SUV explosion hugely wasteful, but it didn't make us any happier.

"Suburban land values are inversely related to commuting costs"

or is it commuting time? if it was costs, suburban fringe prices would have risen again with gasoline price declines.

Not if everyone thinks gas will go back up. This seems to be the prevailing attitude of almost everyone I talk to, and not just TODers, but most of the everyday, GOP-voting Dallas-ites I know too.

Commuting costs are a function of both the resource requirements (depreciation on vehicles, gasoline, oil, etc.) and time.

My statement above was simplified; commuting costs are one component of suburban land prices. All things equal, yes, land prices would rebound with declining commuting costs. But, another factor in land prices is aggregate regional demand, itself a function of population and income. Incomes are declining, and as noted, their is a more widespread appreciation of gasoline price volatility that may be influencing buyers' willingness to lock in to distant residential sites.

Incomes will be redistributed alright, albeit somewhere so low compared to current scales that it's hard to imagine today. The redistribution process will involve pitchforks, that much is certain.

Other than that, you're right that peak oil has nothing to do with lower wages; nor does it with any other aspect of the financial crisis. It's a tiresome shame that that is so hard to understand for those focused on energy prices and supplies. Down the line, no matter what the price for oil becomes, you won't be able to afford it anyway. Did I mention that it won't be transported any longer either, at least for personal consumption? Just look at how the shipping sector is tanking already.

Financial institutions need to write down debts and cut their loan portfolio's in far higher amounts and percentages than they have so far, a process that will kill off the majority of businesses, of production, manufacturing, transport, you name it. It will all be made much worse by governments saddling their nations with trillions of dollars in additional debt through rescues and stimuli that have zero percent chance of accomplishing anything other than delaying downfall by a few weeks or months, instead of using that new-found debt to supply basic needs for their citizens.

Debt levels throughout society dwarf any and all measure of accumulated wealth. hence there is no wealth left. None. The blind belief that this is somehow related to peak oil keeps people from recognizing what is truly happening all around them. Well, be prepared to be unpleasantly surprised.

Ilargi, personally I think the credit implosion is the first (and quite possibly fatal) blow. Peak oil will inflict the next blow (if the financial system is still alive, this will surely kill it). Then, for variety, climate change will reduce crop yields and promote mass migration and possibly wars, if they haven't started by then already. No wonder why I don't get invited to too many cocktail parties... ;-)

Ha! Classic. My life, once I became a DINK, was one long cocktail party, with stuff. Once I re discovered Peak Oil and Peak Housing (ex - was a mortgage broker) out of the house and now only cocktails! It is a disease, but the consequences are so dire...OH well!

Only by current standards.

Imagine if all money, credit and debt went away. Imagine further that the IDEA of debt and credit went away as well. Then what we'd be left with is remaining natural capital (significant but declining), built capital (significant but needing a large energy surplus to keep it going), human capital (huge, but a large % rendered obsolete, but can be regenerated) and social capital (potentially huge if we can get used to lower living standards and have a different carrot).

All wealth is not gone, only as measured by current system. It remains to be seen if this is the same thing.

Hey yeah,

Let's all imagine we don't have to pay off our debts, that we can throw out the system when it doesn't please us anymore. The world's accumulated debt, meanwhile, is much bigger than the world's accumulated wealth. The debtor may dream of discarding the current system, but the creditor would have to comply, and why would (s)he want to "imagine" that (s)he's not owed anything?

And what would the creditor be able to do to collect on the debt if the debtor can't pay and doesn't plan on giving up the collateral. Creditors are much more reliant on the good faith of the debtor than the other way around.

Nice fantasy. Now you go tell that to the guy who comes to evict you from your home.

Ilargi, I'm not sure I fully understand you ... IMO money and debt are not wealth, they are a support system, a tool to make bartering of wealth easier ... take all the money/debt away and all the world's accumulated wealth remains ... it's just that the ownership of the wealth may have changed in the process and the money is no longer worth what people thought it was.

Also, IMO, the way the world works is very complex and interconnected ... it is a world of completely abnormal growth, nobody understands how it works (especially experts and politicians!) ... any growth is typically exponential and unsustainable.

IMO what we have at the moment is a cluster of linked failure modes all feeding off each other ... hence the difference of opinion on the proximate cause(s).

We are now post peak oil, post peak 'net exports' of oil, post peak energy per person, in systemic world economic failure, in a systemic banking failure, the ecosystem is failing around the globe etc. etc, all caused by an unsustainable exponentially increasing human population striving for a better life through economic growth.

The cause of the exponential growth of population and all it's support structures is the exponentially increasing consumption of fossil fuels.

My point is it depends how you define 'wealth'.

You are wealthy in insight in knowledge and insight. I am wealthy in potatoes (or I was). Society HAS measured weathth in financial marker terms, (and continues to do so based on the Reuters news story I just read 'Is There Life Below Dow Jones 7,000?'.

If you only meant paper wealth then I mostly agree with you. But after paper system is over, and the casualties be what they may, there will still be a great deal of wealth existing. For one thing, we get 10^16 W of annual insolation from the automatic sun:

So we're not broke, just in hock.

Nate,

While I agree with the spirit of what you are saying,

the graph you have used appears to have come from this source:

http://www.oecdobserver.org/news/fullstory.php/aid/2083/

While the numbers for wind(100TW) and FF(10TW) seem to be about correct, the statement about wind energy:

"annual load factors of wind generation in countries with relatively large capacities, such as Denmark, Germany and Spain, are just 20-25%: large wind turbines are thus idle for an equivalent of 270-290 days a year!"

suggests no understanding of wind power, even a turbine that has an average capacity factor of 20%, generates some electricity >90% of the time, but rarely ever at full capacity.

The value of stream runoff of 1TW(1000GW),( if this implies hydro electric generation) is a gross underestimation, the US and Canada with 8% of worlds land area, have a potential of 500GW.

Not sure what happened to nuclear?

Smil's graph see seems to be used a lot without critical evaluation.

A couple of comments..

First, I fully agree that the current financial crisis is not related to peak oil in any significant way. The curves that track wealth distribution, credit outstanding, etc, mimic those of the Great Depression, except current ones exaggerated compared to the late 20's. We've been heading to this collapse for a while.

To Nate's point on capital one the debt unwind progresses.

The difference between the 1930's and now is resource availability (and, to some degree, human capital). In the '30's, we had vast, relatively untapped sources of raw materials (oils, metals, much of the raw material needed for a growing industrial society. We also had a workforce that had far more experience in agriculture and small scale basic manufacturing than we do today.

Now, while more people are learning small scale farming as a skill, it's far rarer than it was 80 years ago. Too many of us are service or 'knowledge' workers. I'm a systems analyst. I can swing a hammer and use a hand-saw, but I don't have the skills of even an apprentice carpenter. My wife and I are just starting to try and figure out how to supplement our food with backyard gardens, and, if last growing season was an indication, we're a long ways away from being good at it.

As the debt unwind progresses to the point where whatever society is left starts to recover(in 3, or 5, or 15 years), that society will face the issues of lack of resources, climate change, food availability, and perhaps a lack of the right kind of human capital.

I think any significant recovery from the financial crisis will be short-circuited by human overshoot. The time of a growing economy is over. Sharon Astyk thinks that the most likely future for the US, and the world, is poverty. I think it's poverty, and fewer people.

I don't think the current unwind this year is peak oil driven, I do think peak oil, and other issue will dominate when we start to recover from the financial unwind.

Michael

I simply don't believe that

getting into the mess may or may not be independent of the actual amount of stuff you burn but the actual point at which it breaks is linked to "peak net bonfire day".. basically a "rob peter too pay Paul tomorrow" economy is fine as long as the rate at which you create new wealth is enough to pay the "net global interest rate"(can't think of a good term go with me I'm a bit thick) and creating new wealth means making things and services..and making things and services is basically a consequence of how much stuff you can burn..

so that the rate at which you need to de-leverage has to be matched in some broad sense by the rate at which you can increase the rate of burning stuff...

if the banking system becomes stressed then the answer was to increase wealth creation to pay it back.. and duly off "they" went (they being the human race, the market, whatever..insert political bias here) ....to try and make the bonfire bigger

at $157 dollars a barrel the flames still grew no higher game over... how much lag is in the system too absorb differences between the required de-leveraging rate and the rate at which the the bonfire must grow is complex and debatable but in the broad analysis is actually pretty obviously not infinitely stretchable..

in hindsight the elastic snapped almost immediately! surprised me a bit that..

The perception issue of "what happened" arises because spectators dissect the problem into components and analyse part of the problem as though it was the whole thing.. which doesn't work.

you need to look at the whole thing...

think of the counter-factual.. there is another 10 trillion barrels of easy oil in the ground.. the bonfire could have expanded for some time and the problem would never have occurred this decade. Even if we all concede the issues concerning the regulatory failings of the financial system are the same.

an over simplification? perhaps but my point is many observers over complicate the issue and take too detailed a look at some specific part. which in this instance is going to throw up the wrong answer

The credit bubble was going to burst anyway, it just needed a proximate cause. $147 oil was as good as any. Plus, people forget that after every oil shock there has been a recession in the past 100 years...when each $10 increase in the price of oil per barrel takes $70B of money out of the U.S. economy, it's no wonder.

A $100 increase per barrel over a one year period is equal to the entire stimulus plan. Which is why the stimulus plan will be almost completely negated once oil increases in price.

It is strange how quite a few of us were talking about the likely impact of peak oil on the financial system for years before it hit. I know I mentioned it way back in 2007, when I wrote an article for actuaries about the it, and when I wrote a guest post for The Oil Drum (before I was on the staff).

I don't have a link to the original, but commenter MicroHydro reports that Hubbert's writings include the following, which was the subject of a seminar he taught, or participated in, at MIT Energy Laboratory on Sept 30, 1981:

It is impossible to have a monetary system that needs to grow exponentially, when resources do not!

"We've been heading to this collapse for a while."

And we've been heading up the slope toward peak oil for a while.

I wonder what angel thinks inflated the credit bubble if not the expectation of ever more growth based on ever more access to ever more oil (fostered by an insane ideology that eternal economic growth was possible, desirable, and essentially inevitable).

Blind belief somehow?

All our money is a claim on resources and energy in the present and in the future. All our energy and resources generation and extraction are all tied to the current infrastructure we use. All our current infrastructure is tied to petroleum production.

This is not a one-theory-fits-all argument. It is merely stating the obvious that our financial problems are, in fact, driven by our energy and resource problems.

If you want to truly realize what's happening to the world around you, you can't be tied down to the broken abstraction of money. Tied to that abstraction, one cannot see the real yet declining wealth still available, as Nate alluded to.

It is most certainly not. To understand that, you have to look at the specifics of money itself, as used in a fractional reserve system. 99% of our money is a claim on nothing at all.

Actually, Ilargi, he's right. That 99% that you are worried about really is a claim on present and future energy and resources, even in a fractional reserve monetary system. Of course, that claim may not be satisfied or the real value of the claim may drop. But it seems like you both agree on the bigger picture.

No, only the remaining 1% is. That is the essence of the problem here.

No, the essence of the problem is that you already understand that money, as a tool invented by humans, is about to break because in the future when people actually try to spend the currency, then the realization will hit that there aren't the resources to back 99% of those dollars.

The tool has not broken yet, and as such, each person out there still has the valid idea that their bills and coins will be useful in making claims on resources and energy.

And for each individual person out there, they are right. Each dollar out there is still a valid claim on energy and resources, as long as not too many of those dollars start making claims at the same time.

We are on the same page as far as the big picture is concerned, it's just a dangerous idea that our monetary problems are somehow self-contained within the realm of finance and not connected to the real world. This abstraction, the confusing of the map for the territory, is also part of the problem.

Correlation is not the same thing as causation. However, it may very well suggest that the two things that are correlated share a common cause.

You are right that peaking of oil (and all non-renewable resources, really) may not have directly caused the festival of over-leveraging and the catastrophic de-leveraging that is now following. However, I would suggest that the two phenomena might both be sequillae of a common pathogen: a pervasive, ideologically-driven, delusional structuring of an entire society (world, really) around the patently irrational and unsustainable idea and ideal of infinite exponential growth. When you have an entire economy structured on this idea, then what you get is an economy that burns through its non-renewable resources as rapidly as it can, rather than trying to conserve them as the priceless irreplaceable things they really are. When you have an entire structured on this idea, then what you get is an economy that piles debt upon debt and risk upon risk until the entire edifice must inevitably fail massively and collapse in a ruin.

Our thinking has been wrong for decades, centuries really. It has misled us, and now we get to see the inevitable, catastrophic consequences.

+5

Every increasing resource extraction and a highly leveraged financial system both assume the same thing: growth is good/desirable and possible for many more generations.

an analogy: it all seems to me a sort of old fashioned spring run geared clock. The clock can be of any size and have a bigger or smaller spring but when the mechanism is fried it doesn't matter about the size of the spring or how wound up it was the whole thing is toast.

From the dedication issue of the Hubbert Center Newsletter. According to Ivanhoe:

"Hubbert wrote virtually nothing about details of the “decline side” of his Hubbert Curve, except to mention that the ultimate shape of the decline side would depend upon the facts and not on any assumptions or formulae. The decline side does not have to be symmetrical to the ascending side of the curve - it is just easier to draw it as such, but no rules apply. The ascending curve depends on the skill/luck of the explorationists while the descending side may fall off more rapidly due to the public’s acquired taste for petroleum products - or more slowly due to government controls to reduce consumption."

http://www.hubbertpeak.com/Ivanhoe/HubbertCenter_97-1_Ivanhoe.pdf

I believe he also wrote some about the likely financial implications of peak oil. I would need to do a little looking to find the references.

Very sobering Gail. And a nice logic flow IMO. As you say, even though the probability can’t be quantified, the pieces of this potential puzzle appear as though they could readily fall into place as you describe. I’m sure others here can detail it better but the little bit of pre-WWII Germany history I do recall reminds me of the position many countries may find themselves in under your model. Perhaps even the USA to some degree. The one aspect of your offering I find difficult to accept is the possibility (let alone probability) that most of our 300 million population could adjust (read: survive) the type of transformation you offer. Such as you say: “I would expect that the renaissance, when it comes, would begin with basic human needs, in local communities and local agriculture. People will grow their own food, and trade with others in their community.” If only 20% of the population cannot function in such a system we would have 60 million folks with no method of supporting themselves. And as I look around I feel the 20% figure is grossly optimistic.

From this starting point we can each paint our own worse case scenario. But let the historians correct me: there have never been a people who willingly accepted such a fate without striking out violently against those who have the necessities of life. Such force could be applied domestically but, if history is any model to adhere to, governments have commonly turned such angst against other countries.

I suppose one could write an article on these issues alone. I am not sure I want to do it--it would be a depressing and worrisome thought exercise.

It does seem likely that if an adverse scenario such as Figure 2 happens, population will fall, with some parts of the world affected more than others.

The big problem with the 'loan repayment problem' is that you basically assume that the amount of money existing is related to the size of the economy.