Economic Impact of an Energy Downturn - Revisited

Posted by Gail the Actuary on February 11, 2009 - 10:18am

Last spring, I was asked to give a short talk about the expected economic impact of an energy downturn, as part of a public health program called "Converging Environmental Crises: A Teach-in on Energy, Climate Change, Water, Agriculture and Population." This is the text, which has been posted previously on The Oil Drum. These are the PowerPoint slides I show. This is a link to the recorded version of my talk.

Good afternoon. My name is Gail Tverberg. Some of you know me as "Gail the Actuary" on TheOilDrum.com web site. The Oil Drum is a web site about energy and our future.

Today, I will be talking to you about The Expected Economic Impact of an Energy Downturn. If, after this talk, you would like to learn more about peak oil and about resource depletion issues of all types, TheOilDrum.com is a good site to go to for more information.

Let's talk a bit first about the energy downturn. As everyone is aware, the price of gasoline and diesel has been rising recently. The reason the price is rising is because the world's supply of oil cannot keep up with demand.

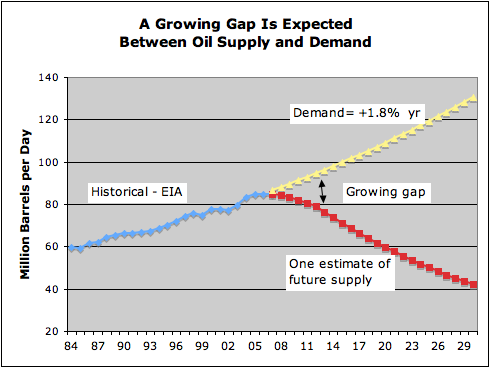

I have illustrated the situation we are facing in Figure 1. In this chart, I show demand increasing in the future at about the same rate that consumption has increased in the past. One reason for increasing demand is growth of economies of developing countries such as China and India.

The supply of oil has leveled off. Oil production for 2007 was about the same as it was in 2005 and 2006. Many people believe that sometime in the next few years, supply may actually begin to fall. Even if supply remains level, as it has in the past three years, there will be a growing gap between expected future demand and supply.

Why Does a Drop in Oil Production Make a Difference?

Why does a drop in the production of oil, or for that matter, any type of energy, make a difference? After all, oil doesn't cost a lot. We only pay about 4% of the US gross domestic product for it.

In many ways, oil is like food for your car, or food for the earthmover that makes our roads. Without food, we can't do anything. We would starve. Without oil, or the fuel made from oil, all of our big equipment won't work. Our electric power plants use other types of fuel, but if they don't have the fuel they need, we won't have the electric power we need either. Our houses will be dark.

We talk about substitutes, but in the real world they are still a very long way off. Think about plug-in battery-operated cars--that's the kind that use only electricity. First of all, we really don't have this kind of car perfected. Even if we did, it wouldn't solve our need for a whole lot of other kinds of vehicles, like semi-trucks and earth-moving equipment.

Suppose we did have the plug-in cars perfected. We still would have to figure out how to build the cars in quantity. Engineers are looking at the possibility of using lithium batteries, but the supply of lithium isn't necessarily sufficient for making millions of batteries for cars.

We also have to think about how people will pay for all the new cars. If there isn't a good supply of oil, the old cars suddenly are worth very little. How many people are going to be able to buy a new car, if they can't trade in their old car as a down payment on the new one?

Scientists have looked at a lot of other solutions as well, but they all seem to be a long way off. It is hard to get people to tell us the truth about the problem. Politicians don't want to admit there is a problem that they don't have a solution for. Even a publication like Scientific American won't admit there is a problem. They would like us to think that our scientists can fix any problem. No one wants to admit that the solutions they are looking at are a long way off.

Earth Is Finite

What is happening is that the earth is finite, and we are starting to reach some of its limitations. At this point, most of the "easy to extract" oil has already been removed. There is still oil in the ground, but what remains is becoming more and more difficult to remove.

When we try to find alternatives, we encounter limitations of other types. In some situations, natural gas might be a substitute, but in North America it is also in relatively short supply. Coal is in better supply, but it has serious climate change issues.

We hear a lot about ethanol from corn. Growing corn for ethanol requires huge amounts of agricultural land and fresh water. Both agricultural land and fresh water are in limited supply. About 25% of the corn we grow in the United States is now being used to produce ethanol. Even using this huge amount of corn, we don't produce very much ethanol. The energy content of the ethanol produced is equal to only about 1% of energy of the oil we use. Clearly, there is no way we can scale up this process, to cover any reasonable shortfall of oil.

Even the minerals that we might use in batteries, and the uranium we might use in nuclear reactors, are becoming increasingly difficult to extract. We have already removed most of the high quality ores of many minerals. What is left is ores of lower concentration. These ores can still be extracted, but it takes more energy resources to process this ore. The energy resources used for processing the ore are often oil and natural gas, and they themselves are in increasingly short supply.

Immediate Economic Impacts

We are all aware that the price of oil is rising. With the increase in price in oil, the price of things made from oil, such as gasoline, diesel fuel, and asphalt also rises. In some cases, it is possible to substitute one fuel for another. Because of this, prices for other fuels, like natural gas and coal, also tend to rise. Electricity is made from coal and natural gas, so its price tends to increase as well.

Food prices are also rising. This is partly because oil is used in growing crops and transporting them to market, and the cost of oil is higher. Higher food prices also reflect the fact that food production is not keeping up with demand, now that demand is so much higher because of biofuel use.

Impacts of Higher Food and Oil Prices

A major impact of higher food and oil prices is to squeeze out discretionary spending, such as eating out at restaurants and flying overseas on vacation. Some students may have to temporarily drop out of college, if their families can no longer afford to help with tuition. Families will cut back in many different ways to keep their budgets balanced.

Another impact of higher food and oil prices is more defaults on loans. We first heard about higher default rates on subprime mortgages. As prices of food and energy continue to rise, defaults can be expected to spread to other kinds of loans, such as credit card debt, auto loans, and student loans.

As families cut back on spending, financial difficulties can be expected to spread to businesses. Some types of businesses that are particularly vulnerable include restaurants, airlines, auto manufacturers, and homebuilders. Businesses with high levels of debt are especially vulnerable, since a drop in revenue is likely to make it difficult to make loan payments.

Financial institutions, such as banks, hedge funds, insurance companies, and pension funds are also likely to be affected by rising default rates. When individuals or businesses take out loans, these loans are often held by one of the various types of financial institutions. If there are defaults, it adversely affects these institutions. Banks and hedge funds often borrow money themselves, so they may find themselves squeezed in the middle if default rates rise. Insurance companies and pension funds may find themselves unable to meet their obligations, if defaults become a serious problem.

Finally, recession is an important impact of higher food and oil prices. Higher energy prices in the past have lead to recessions, including the very severe recession that took place in 1973 to 1975. It is likely that higher energy prices are one of the causes of the current recession.

Longer Term Impacts

The graph I showed earlier suggested that the gap between oil supply and demand is likely to get wider, as time goes on. If the shortfall in oil continues to get worse, and it is not possible to offset this shortfall in other ways, this recession may become permanent. The recession may get worse with time, turning into what we would think of as a long-term depression.

We are now reaching limits of many kinds. One way of representing the economy at various points in time is as disks of various sizes. Each year, society has various resources available to it, in terms of oil, natural gas, fresh water, soil productivity, minerals of various types, good climate, and people available to work with these resources. Based on the investments we have made over the years, society is able to produce a collection of goods and services using these resources. The amount of these goods and services has been growing. Let us look at this graphically.

In the recent past, the economy has been growing:

With a long-term recession, it may change to a no-growth economy:

More likely, the economy will decline as resources deplete:

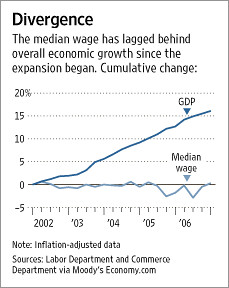

(TOD readers: In the article The financial crash has a simple cause and a simple solution, Jerome a Paris discusses the fact that since 2002, the US median wage has stagnated. Thus, for a large share of the population, we have already reached the "no growth" scenario. This lack of growth in median wages is likely the reason that the financial services industry developed new forms of loans that made home-buying look more affordable than it really was. The lack of growth in median wage is also a likely reason that those same schemes are now falling apart. To the right is the graph Jerome showed.)

With a declining resource base, the median wage, adjusted for inflation, is likely to decline. This decline in median wage means that default rates on loans are likely to increase, and that discretionary spending will continue to decline.

Future Promises

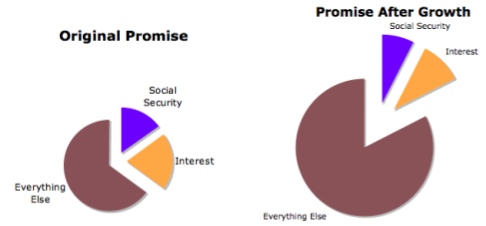

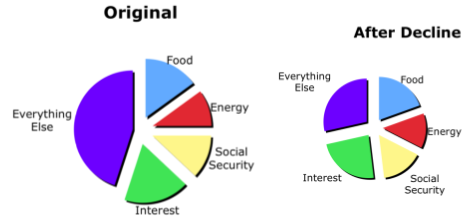

It is not very obvious just looking at an array of discs, but a change from a growing economy, to a flat or declining economy, is really a major change. With a growing economy, future promises are relatively easy to fund:

The reason promises like interest payments and social security payments are relatively easy to fund in a growing economy is because these payments are generally not growing as fast as the economy as a whole. When promises such as these are made, the expectation is that the payments will be less of a burden in the future, because the economy will have grown. With this growth, there should be plenty of funds left over for other things.

With a flat or declining economy, funding for promises becomes almost impossibly difficult. Food and energy costs become a bigger share of the economy, over time, because of energy shortages. Future promises like interest, social security, and Medicare payments also become bigger, relative to the total. I have illustrated this in another graph. The combination of the two types of increases, that is the food and energy costs plus the cost of future promises, becomes a huge problem. There is not enough left over for "everything else".

Lenders Will Soon Catch on to Decline

If the economy is in long-term decline, it will not be very long before lenders start to catch on. Some creditors may actually figure out that the economy is not growing, and that it is not likely to grow in the future, because of energy shortages and other limits. Other lenders may only figure out that the default rate is very high, and, because of the way the economy is headed, it can only go higher. Regardless of their reasoning, many lenders are likely to come to the same conclusion, namely, that it no longer makes sense to offer loans.

For the United States, the balance of payments deficit is very much like debt. For years, the United States has been importing nearly twice as many goods as it exports. Once trading partners realize that the US economy is in long-term decline, they will realize that it will be almost impossible for the United States to make up for its export shortfall in the future. They are also likely to realize that buying US treasury bonds is not a good substitute for an even trade balance, since the Treasury bonds are likely to decline in value in the future, in terms of the goods they can buy. These issues could lead to a crisis in US imports of all kinds.

World Is Headed for a Credit Unwind

It seems likely that the world is now headed for a major unwind of credit. There has recently been a crisis in the financial markets. This crisis looks very much like the beginning of a major shift toward reduced credit availability. As energy supplies get tighter, economic conditions are likely to get even worse. People will be spending more for food and gasoline, so will be more likely to default on loan payments. If people are out of work, they are more likely to share living spaces. This will reduce demand for houses, and further depress prices.

I expect that the shift toward reduced credit availability will expand in the future. This may even be the "great unwind", in which debt and financial instruments of all types, including derivatives, become very much less common. The real question now is what form the unwind will take. How major will it be? Will it take place in steps, or will large sections of it occur all at once?

The impact of a credit unwind is very much like cutting up a person's credit cards. The person (or business or government) still owes as much debt as in the past, but the organization has no way of obtaining new credit. The debtor must now repay the loans out of current income, in addition to paying current expenses out of income. For many, this will not be possible. Bankruptcy seems likely for many, including a large number of businesses and some governments.

It is possible that a correction to the balance of payments situation, mentioned previously, could be part of the unwind. If this happens, imports of all kinds could drop by as much as half, very quickly.

Looking Ahead 20 or 30 Years

If we look ahead 20 or 30 years, it seems likely that the world will be very much poorer. Personal autos may be rare. Electricity may be unreliable. It is likely that we will have much less in the way of goods and services than we have today. A growing population may add to our problems. If the smaller supply of goods and services is divided among more people, living standards are likely to be much lower than they are today.

If the world becomes much poorer, I would expect social security and Medicare to be drastically scaled back or even eliminated. There will be so little goods and services in total that society cannot afford to set aside much for the disabled and elderly.

I expect that in 20 or 30 years, many business and governments will have failed. Bonds of these businesses and governments will have little value. Stocks of companies that remain in business will continue to have value, but this value may not be high compared to the cost of available goods. Inflation rates are likely to be high, reflecting the lack of goods and services for people to actually buy if they do have money.

Insurance companies and pension plans own stocks and bonds of other companies. When these other companies fail, the insurance companies and pension plans are likely to encounter financial difficulty as well. People who were counting on insurance companies and pension plans for benefits are likely to get nothing, or to receive benefits that are worth very little, because of hyperinflation. I expect most people will choose to continue to work as long as they are physically able to work, because of the poor retirement and pension benefits available.

My expectation is that over the next 20 or 30 years, globalization is likely to be scaled back. A decline in air travel will make it more difficult to manage international businesses. There will be less trust for other countries, because of all the defaults. Countries expecting to import goods are likely to need a corresponding amount of goods to export.

Nature of the Transition

The exact timing and shape of transition from our current economic system to the one that will be in place twenty or thirty years from now is not yet clear. Ideally, the transition will be a slow one, planned by governments. Even if it is slow, it will not look all that slow to people who are laid off, or to people who can no longer afford to drive a car.

It seems at least equally likely that the transition will not be smooth. Many people talk about the possibility of some type of implosion, if our current debt situation cannot be straightened out, or if rising food and gasoline prices make the debt situation worse.

We would like to think that our current financial system can handle multiple failures by banks, money markets, hedge funds, and insurance companies. It is possible, though, that failures will cascade through the system, because each institution owes money to multiple other institutions. If too many institutions fail at once, it is possible that the safety nets in place for the financial system will not work. A lot of people could lose a lot of money, overnight, from multiple failures of institutions holding our money.

There is a second way cascading failures of financial institutions could work out badly. Suppose multiple failures cascade through the financial system, and regulators actually succeed in keeping financial institutions propped up. It is possible that all of the extra cash added to the system may cause rapid inflation, or hyperinflation. If this should happen, we might all find that our money will purchase very little, almost overnight. Our bank accounts would still be full; we just wouldn't be able to buy much of anything.

Unfortunately, the current safety net in case of cascading failures is fairly limited. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson has proposed a new regulatory structure that would be wider ranging, and presumably provide a better safety net. Getting agreement on what this new regulatory structure should be is likely to take months. In addition, once a new structure is agreed upon, it is likely to take at least another year or two to fully implement the new plan.

Meanwhile, the problem with failing financial institutions is a very current one. If recent trends continue, it is possible that several large financial institutions may fail within the next few weeks or months. If failures occur this quickly, it is doubtful any new structure will yet be in place. We can only hope that ad hoc methods, such as those used by the Federal Reserve so far, will be successful in keeping things patched together.

Health Care Services

Since this talk is part of a series of talks related to public health, I will close by making a few comments about changes I expect in the healthcare field.

I expect that over the next 20 or 30 years, health care services are likely to be drastically scaled back. In a poorer world, I expect that services of all kinds are likely to become less important relative to actual physical goods, and medical services will not be an exception. Fees paid to physicians are likely to be scaled back even more than health care services in general, because few will be able to afford the high fees physicians currently charge.

Public health may become more important, rather than less. If people are poorer, they may look to the government to provide some basic level of service. We might do well to look at how some of the poorer countries are handling healthcare now, for some ideas as to what we might do in the future.

If there is a shortage of oil, transportation is likely to be an issue, for both healthcare employees and for patients. Smaller facilities, within walking distance of patients, may become more important.

Because we are running into limits in so many ways, I expect that electrical interruptions will become more common in the next 20 or 30 years. These may even become a problem early on, for a whole host of reasons, including lack of water for cooling, lack of fuel for power generation, and poor upkeep of the electrical grid. Healthcare providers would be wise to plan for the day when elevators and electronic records may not be available.

Conclusion

I am sorry all of these predictions are very downbeat. As the world reaches it limits, it is clear that the growth paradigm that we are used to will have to end. Decline is in fact quite likely. The financial world does not deal well with economic decline, so economic problems are likely to be among the more severe ones facing the nation and the world, in the years ahead.

Thank you.

Hello everyone,

i'm relatively new here and i would like to know what are your toughts about carbon capture and sequestration. I've been reading about that and i've gotten some mixed ideas. Do you consider it to be a tecnologie that is worth investing our time and money or is one of those that will only be avaible in 20-30 years time and therefore too late to create an impact. And even more so if during that period of time we can put all our resources into something that can avoid the constrution of any more coal and gas power plants and ensuring, at the same time, a very much significant reduction of the CO2 emissions?

Please see if desired DLR news: http://www.dlr.de/en/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-13/135_read-13869/ and

report: http://www.greenpeace.org/raw/content/international/press/reports/energy...

Rui Cruz

I went to a public lecture on carbon sequestration at Princeton University in 2006. Besides Prof. Socolow I can't remember the name of other researcher who did most of the lecture. The concept sounds fine IF the geological formations that can hold the CO2 are available. Other than that, I can't say much.

Euan Mearns is working on an analysis on CCS and it should be posted soon. The bigger question that few seem to be asking is that although there is plenty of 'energy' around us: fossil fuels, solar, wind, etc. the amount that is AFFORDABLE by a population who has spent themselves into a corner in a fiat currency regime is a monumentally different question than the geology itself.

IF we had lots of energy resources out there: coal, wind, oil, gas, solar that cost $10 per barrel of oil equivalent to procure and deliver, then this economic depression would be shortlived as the 'gain' from energy would ripple through the economy. As such, once oil and gas depletion catch up to the drop in demand we are going to be faced with energy that can only be afforded by the richest countries and top echelons within those countries. Historically, this drop in living standards (from whatever they were previously) has led to resource wars. So to use 30% or so of the energy content in coal to sequester it might be something that adds to unaffordability.

Lower consumption is only answer. The more we try to heal the economic growth business-as-usual engine the less affordable future energy is going to be for all.

I hope Euan and others can more specifically address your CCS question in detail - but people need to be shouting from the rafters that it is not how much energy we have access to, it is how much we can afford. Matt Simmons suggested $100 trillion to upgrade the rusted oil/gas/etc energy delivery systems worldwide- where is that money going to come from? We are having fits on $800 billion bailout packages....

Thank you all for your reply. I'll be looking forward to hearing from Euan Mearns then.

Concerning the topic posted I really also think that you should advocate energy restrains, improving efficicies everywhere and understand the concept of finite resources...i would like to believe that there is still time...

Rui Cruz

PS Thanks to everyone that make TOD possible! ;)

Everything I have seen written about CCS is that the technology is many years away, at best. It is not clear we will ever be able to do it on scale.

If we are able to do it, the big issue is that we will have to burn vastly more coal that we would otherwise, in order to power the process. If CCS doesn't work perfectly we may still end up with as much CO2 as ever, and will end up burning our coal a whole lot faster.

We also don't know what the secondary impacts of CCS would be. We have seen that the Three Gorges dam in China seems to be causing earthquakes. The amount of CO2 to be sequestered is vastly larger than the amount of coal removed. How would it really work out?

Pumping a huge amount of CO2 into the ground and hoping that nothing catastrophic happens to suddenly and unexpectedly release it all at once into the surrounding area sounds to me like a very bad idea. I remember what happened to those people in Africa a couple of decades ago when a lake suddenly belched out a bunch of CO2, and suffocated an entire village. This just sounds like another one of those big technofixes that come with future huge unintended consequences that no one thought about at the time.

Exactly. Same with proposals to inject SO2 aerosols into the stratosphere to increase albedo, or fertilize the oceans with Fe to increase productivity & sequester carbon when phytoplankton dies & sinks, etc. All represent desperate attempts at a technofix that may or may not work and are certain to have unpredicted (& unpredictable) consequences. Remember: "First, do no harm."

Sequestering Co2 is just another example of the techno freaks expecting technological ingenuity to cure the problems brought about by technology and engineering in the first place.

Always trying to find a way for technology to further growth and BAU, which will create new problems requiring new techno fixes.

Why do we continually fall into that trap?

If I wanted to be cynical I would guess some people will benefit.....bankers, corporate CEO's, politician's, Wall street................

Why is it when new technology comes along we always end up needing more resources, needing more energy and create more pollution.

If technology allows for more efficient vehicles, we just build more of them, if it allows us to use ground beef more efficiently we build more McDonalds, if it cures a disease we create more people, if we build a cheaper bridge, we build more of them, if we can build a taller skyscraper we do so.......always more.

It wasn't CO2 . I believe it was SO2, common in volcanic regions.

It was in fact CO2. Lake Nyos, Cameroon.

Carbon sequestering information for those who do not want to wait. It is happening now at several tens of millions of tons/year worldwide. Civilization is generating abut 25 billion tons of CO2. But the amount of CO2 offset by solar power is on the same scale. Nuclear power worldwide offsets 2 billion tons of CO2 per year. Plus when CO2 is used to get more oil then it is not a net reduction depending on how it accounted. Of course getting towards CO2 neutrality by storing as you use and getting more oil is better than using oil/coal and not storing. Plus enhanced oil recovery also helps with Peak Oil, which I think some here recognize as a good or necessary thing.

In 2007, Jason Burnett, EPA associate deputy administrator, told USINFO. "Currently, about 35 million tons of CO2 are sequestered in the United States," Burnett added, "primarily for enhanced oil recovery. We expect that to increase, by some estimates, by 400-fold by 2100."

http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/WO0710/S00788.htm

The Japanese government is targeting an annual reduction of 100 million tons in carbon dioxide emissions through CCS technologies by 2020.

http://www.carboncapturejournal.com/displaynews.php?NewsID=238&PHPSESSID...

There is also the potential to store CO2 in biochar [grow plants and then bury them as charcoal, 1/2 to 1 wedge by 2025.

http://www.ehponline.org/members/2009/117-2/innovations.html

Carbon can also be placed into new kinds of cement.

The MIT Future of Coal 2007 report estimated that capturing all of the roughly 1.5 billion tons per year of CO2 generated by coal-burning power plants in the United States would generate a CO2 flow with just one-third of the volume of the natural gas flowing in the U.S. gas pipeline system.

The technology is expected to use between 10 and 40% of the energy produced by a power station.

Industrial-scale storage projects are in operation.

Sleipner is the oldest project (1996) and is located in the North Sea

where Norway's StatoilHydro strips carbon dioxide from natural gas

with amine solvents and disposes of this carbon dioxide in a deep

saline aquifer. The carbon dioxide is a waste product of the field's

natural gas production and the gas contains more (9% CO2) than is

allowed into the natural gas distribution network. Storing it

underground avoids this problem and saves Statoil hundreds of millions

of euro in avoided carbon taxes. Since 1996, Sleipner has stored about

one million tonnes CO2 a year.

A second project in the Snøhvit gas field in the Barents Sea stores

700,000 tonnes per year.

The Weyburn project is currently the world's largest carbon capture

and storage project. Started in 2000, Weyburn is located on an oil

reservoir discovered in 1954 in Weyburn, southeastern Saskatchewan,

Canada. The CO2 for this project is captured at the Great Plains Coal

Gasification plant in Beulah, North Dakota which has produced methane

from coal for more than 30 years. At Weyburn, the CO2 will also be

used for enhanced oil recovery with an injection rate of about 1.5

million tonnes per year. The first phase finished in 2004, and

demonstrated that CO2 can be stored underground at the site safely and

indefinitely. The second phase, expected to last until 2009, is

investigating how the technology can be expanded on a larger scale.

The fourth site is In Salah, which like Sleipner and Snøhvit is a

natural gas reservoir located in In Salah, Algeria. The CO2 will be

separated from the natural gas and re-injected into the subsurface at

a rate of about 1.2 million tonnes per year

Australian project to store 3 million tons per year starting in 2009

The Gordon project, an add-on to an off-shore Western Australian Natural Gas extraction project, is the largest CO2 storage project in the world. It will attempt to capture and store 3 million tonnes of CO2 per year for 40 years in a saline aquifer, commencing in 2009. It will cost ~$840 million.

http://nextbigfuture.com/2009/01/mit-writes-positively-about-scaling.html

CO2 capture from the air

http://nextbigfuture.com/2009/01/co2-capture-from-air-for-fuel-or.html

Wide plan proposes €1.25bn for carbon capture at coal-fired power plants; €1.75bn earmarked for better international energy links

The European commission today proposed earmarking €1.25bn to kickstart carbon capture and storage (CCS) at 11 coal-fired plants across Europe, including four in Britain.

The four British power stations – the controversial Kingsnorth plant in Kent, Longannet in Fife, Tilbury in Essex and Hatfield in Yorkshire – would share €250m under the two-year scheme.

http://209.85.173.132/search?q=cache:fL4VtwqL1kQJ:www.gassnova.no/gassno...

The governments of Japan and China have agreed to cooperate in carrying out a project to inject carbon dioxide (CO2) emitted from a thermal power plant in China into an oil field. The project will cost 20 to 30 billion yen and will involve the participation of the Japanese public and private sectors, including JGC Corp. and Toyota Motor Corp. The two countries plan to bring the project into action in 2009.

Under the plan, more than one million tons of CO2 annually from the Harbin Thermal Power Plant in Heilungkiang Province will be transferred to the Daqing Oilfield, about 100 km from the plant, and will be injected and stored in the oilfield

Hi Ruibonga,

The main issue with CO2 capture is the same with all other potential solutions to the loss of oil and global warming: scale and the return on marginal energy production. The U.S. produces about 1 to 1 1/2 cubic km of CO2 each year. So say you want to capture the CO2 produced by all of the NG and Coal power plants and store it somewhere. You first would need to build the following facilities on a national scale: filtration & capture, compress/liquification, piping, intermediate storage facilities, storage wells, injection pumps, & monitoring facilities. By the time your all done with that, you discover that the same or less energy and materials would be consumed by building solar & wind farms, biofuel plants, etc.

Because we’ve harvested just about all of the low hanging fruit (oil), the cost, material and energy required to get the higher up fruit (deep sea oil, deep tar sands, etc.) is more than building sustainable alternatives. This is why many crude oil projections that show lots of tar sand or shale oil production enabling oil supply to keep increasing past 2030 are just nonsense. They don’t take into account the consumption of natural gas & water, and the CO2 production and what we could be building instead. As an example, mining all of Canada’s 1.3 trillion barrels of tar sand oil would take 4 times their currently quoted natural gas reserves. And the EROEI for easy to get tar sands (less than 250' deep) is around 2 to 7, which is not good. Current oil is 15 to 30:1 and new wind turbines are above 30:1. Another example is the National Renewable Energy Lab's (NREL) 20% by 2030 wind power proposal. In it, they found that the cost of building wind turibnes instead of coal and NG power plants was only 2% or 3% more over the next 22 years.

http://www1.eere.energy.gov/windandhydro/pdfs/41869.pdf (pg 38 of PDF, 19 of doc.)

After the next 20 years or so of energy consumption, if we don’t have a significant portion of our sustainable energy infrastructure in place, its only going to happen with lots of pain. All that said, if a coal power plant is near the requisite geological strata, and we need the energy, carbon capture might be used, but it will be only a small portion of whatever we use to achieve energy sustainability.

Check out Pamela Tomski’s presentation at the Sacramento Peak Oil conference (Sep 21-23, 2008). She said during Q&A after her presentation that any significant CCS was at least 10 years away. Her's is 9th up from the bottom.

http://www.aspo-usa.org/aspousa4/proceedings/

Is it worth investing in?

Depends on how seriously you think Global Warming is and how addicted we are to grid electricity.

85% of all GW potential in the US comes from CO2.

Almost 50% of all US CO2 comes from buring coal for electricity.

About 36% of all US CO2 comes from burning

oil in transport.

So the biggest single thing we can do is to

eliminate CO2 emissions from coal.

The US is highly addicted to grid electricity which uses 40% of our fuel.

Our whole cushy society is based on cheap power; our houses waste energy, our computers waste energy, we need energy instantaneously at our finger tips, etc.

And the US has enough coal to last hundreds of years at current rates of consumption(longer than even uranium in LWR reactors). Therefore CCS is definitely

a technology worth investing in.

CCS is not 100% capture but runs around 90% capture.

There are three methods of extracting CO2.

One is by removing CO2 from synthetic natural gas produced by the gasification of coal this method requires the least amount of electricity but requires new gas turbine plants instead of steam boilers. So it makes sense for new coal plants that don't emit much CO2. 'Liquifying' CO2 to a supercritical fluid take about <15% of the output electricity.

The second method is amine exchange that removes CO2 from boiler exhaust gases, which can be retrofit to many existing steam plants. 'Liquifying' CO2 here takes <25% of the output electricity.

A third method is oxycombustion( burning carbon with pure oxygen(which requires electricity) which produces a pure CO2 exhaust which must be compressed and

buried.

All these methods produce less electricity

than current coal plants, so nobody likes them.

To this you must add the energy and cost to transport the CO2 to a place for burial.

A 500 Mw coal plant requires 50 rail cars of coal per day, if it were responsible for removing the CO2 might require as many as 250 liquid CO2 tank cars per day to remove it. This is a strong argument for building new generation coal plants at carbon sequestration sites but that also requires a grid capable of transmitting power over large distances.

Another method of carbon capture and sequestration is to gasify coal into synthetic natural gas and pipe that over existing gas pipelines while burying 2/3 of the CO2 at the sequestration site.

Natural gas emits 50% the CO2 per BTU as coal. Gasification is about 65% efficient

and some electricity would be required for 'liquification'. So overall a ton of coal would turn into 1.5 tons of liquid CO2 and 10000 scf of 'clean(er)'natural gas. If that 10000 scf were then burned

in a local gas turbine, it would produce about 1 Mwh(50% of what you get in a normal electric power plant burning coal.

The advantage is that natural gas allows you to use more irregular wind energy and you can recover lots of heat from gas cogen in the form of hot water.

There are 90 billion tons of CO2 storage in old oil/gas fields, another 150 billion tons of CO2 storage in unmineable coal seams and 600 billion tons of CO2 storage potential in deep saline aquifers. These places are well over 2000 feet below the surface and the idea that they will leak all over the places makes as much sense as that natural gas is simply leaking all over the place. The US produces 5.5 billion tons of Co2 per year. We will run out of hydrocarbons before we run out of places to bury them on land.

We can absolutely do carbon capture and sequestration.

To do this we need to either work very hard to rebuild our energy infrastructure or reduce our addiction to wasteful electricity. We will have to do both.

James Hanson gave some testimony about the value of CCS. As I recall he thought it would take 10 years to develop but thought it main use would be for bio-fuel plants.

podcast http://www.ecoshock.org/DNclimate08.html

Hansen wants to burn plants and use CCS to take CO2 out of the atmosphere---a carbon negative process.

Man, he's really worried about carbon dioxide!

Biochar Soil Technology.....Husbandry of whole new orders of life

Biotic Carbon, the carbon transformed by life, should never be combusted, oxidized and destroyed. It deserves more respect, reverence even, and understanding to use it back to the soil where 2/3 of excess atmospheric carbon originally came from.

We all know we are carbon-centered life, we seldom think about the complex web of recycled bio-carbon which is the true center of life. A cradle to cradle, mutually co-evolved biosphere reaching into every crack and crevice on Earth.

It's hard for most to revere microbes and fungus, but from our toes to our gums (onward), their balanced ecology is our health. The greater earth and soils are just as dependent, at much longer time scales. Our farming for over 10,000 years has been responsible for 2/3rds of our excess greenhouse gases. This soil carbon, converted to carbon dioxide, Methane & Nitrous oxide began a slow stable warming that now accelerates with burning of fossil fuel.

Wise Land management; Organic farming and afforestation can build back our soil carbon,

Biochar allows the soil food web to build much more recalcitrant organic carbon, ( living biomass & Glomalins) in addition to the carbon in the biochar.

Biochar, the modern version of an ancient Amazonian agricultural practice called Terra Preta (black earth), is gaining widespread credibility as a way to address world hunger, climate change, rural poverty, deforestation, and energy shortages… SIMULTANEOUSLY!

Biochar viewed as soil Infrastructure; The old saw, "Feed the Soil Not the Plants" becomes "Feed, Cloth and House the Soil, utilities included !". Free Carbon Condominiums, build it and they will come.

As one microbologist said on the list; "Microbes like to sit down when they eat". By setting this table we expand husbandry to whole new orders of life.

Senator / Secretary of Interior Ken Salazar has done the most to nurse this biofuels system in his Biochar provisions in the 07 & 08 farm bill,

http://www.biochar-international.org/newinformationevents/newlegislation...

Charles Mann ("1491") in the Sept. National Geographic has a wonderful soils article which places Terra Preta / Biochar soils center stage.

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2008/09/soil/mann-text

It's what Mann hasn't covered that I thought should interest any writer as a follow up article;

Biochar data base;

http://terrapreta.bioenergylists.org/?q=node

NASA's Dr. James Hansen Global warming solutions paper and letter to the G-8 conference, placing Biochar / Land management the central technology for carbon negative energy systems.

http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/0804/0804.1126.pdf

The many new university programs & field studies, in temperate soils; Cornell, ISU, U of H, U of GA, Virginia Tech, JMU, New Zealand and Australia.

Glomalin's role in soil tilth, fertility & basis for the soil food web in Terra Preta soils.

Given the current "Crisis" atmosphere concerning energy, soil sustainability, food vs. Biofuels, and Climate Change what other subject addresses them all?

This is a Nano technology for the soil that represents the most comprehensive, low cost, and productive approach to long term stewardship and sustainability.

Carbon to the Soil, the only ubiquitous and economic place to put it.

Cheers,

Erich J. Knight

Shenandoah Gardens

540 289 9750

I agree that we're in a big mess, that the credit situation will not ease, and that the future is very uncertain, even threatening. However, I think that declining oil is actually helping us (will help us) on a path more compatible with a livable future.

As long as oil is abundant, any new energy source or carrier will just add to the existing sources (as was found for wind-energy). A gradual decline of oil availability will finally allow other energy carriers or means of transportation to take over, based on cost, availability, and motivation.

That there's a lot of slack in the system is clear: Europeans use four times less gasoline per head of the population than Americans, and they're not exactly frugal either.

Much of our gasoline use is for unnecessary transports anyway: carting live animals a 1000 miles to cheaper slaughterhouses, production in England, packaging in Poland, and sales in Southern Europe. On a smaller scale: driving an SUV to the gym is plain silly.

My guess is that use of gasoline can be reduced by 50% just by organizing the economy a bit different, using strong incentives on fuel economy, creating more room for pedestrians and cyclist, promoting public transportation, etc.

Anyway, poorer is a matter of definition: I like an additional hour of free time per day much more than a new car and a flatscreen television, and I prefer a smaller apartment with 15 minutes cycling to work over a big house with a 1 hour cardrive to work.

If we can make a smooth transition downward, like you are suggesting, then everything is well and good.

The problem is that we are working in a networked system. If we suddenly lose a major share of imports, we could find major changes that seem vastly out of proportion to the decrease in oil availability. Also, the oil availability, could vastly decrease, just because we are unable to import it.

I worry about a loss of electric power to significant portions of the country. If this happens, we will have difficulty transporting oil by pipeline and operating our gasoline stations. We take a lot for granted. If things start falling apart, the smooth transition may not be there.

Gail is correct in that oil is the keystone that holds up the arch of our society. Remove the keystone and the arch tumbles down.

Perhaps a more nuanced analogy would be a tower or iron, much like the Eiffel Tower, held together with bolts. You can lose many bolts in a well-networked tower where each bolt shares the load between many other bolts. The oil economy is like a tower held together with millions of bolts throughout its structure except that the tower is turned on its head. Imagine the Eiffel Tower turned upside down. At the bottom, you have a tiny base with two, three, or four bolts which support the entire weight of the tower. (Imagine the creaking as the wind blows it about!) If bolts higher up the well-networked tower fail, nothing happens, relatively speaking. Some people point to those failures and the concurrent lack of cascading disaster and note how resilient our system is. But, let's say that one of those bottom bolts snaps on a fine spring day in Paris. Hmmm. Not so resilient now.

I am looking forward to transitioning along with many other people who have no trouble realizing that one free hour per day is worth more than a new car. My concern is that this view is not shared by the vast majority of people, who have chosen, over the years, the additional work and the commute, in order to have more consumer goods and a larger house (arguably, a large proportion have also been "running faster to stay in place" as real wages have stagnated or dropped).

So the way I see to a reasonable transition is rationing and planning, and reverse advertising. But how do we generate the will to go there?

For those who are not yet aware, I would recommend looking into the Transition Movement (http://www.transitiontowns.org). It may be an antidote to despair for people who find themselves convinced by analyses such as Gail's, and at the very least, would keep us engaged in a worthwhile pursuit, whether the planet burns or not.

You may end up getting much more than just one free hour a day if your job is in anyway linked to the economy. What job isn't? Smooth transition at his late stage is looking more unlikely by the day.

Great piece Gail. As usual I'm amazed how you can take a series of complex issues and present them in a common language those without an MBA can understand. And then do so without adding a patronizing tone.

Like most here I can foresee the difficult times in general terms. But as you lay it out so well and compact it does come across as overwhelming and unavoidable. Though I've never though of myself as a doomer it's difficult to accept your presentation without expecting a very dark world ahead of us. The time for solutions which might have lessened this sad future have passed long ago IMO. And the current efforts to "fix the system" seem to have the potential to push us towards those very sad times even faster. Your changing growth model is truly sobering. And I woke up this morning feeling so good too.

Sorry I have a hard time being more upbeat. As long a one has an infinite growth model in his/her head, recessions are a temporary phenomenon, and we go through temporary dips as the economy continues to expand.

One a person understands resource limitations, that model goes away. There may still be cycles, but it is hard to see them around a continually expanding economy. A big piece of our problem is that so many promises have been made that depend on growth. If that growth goes away, somehow these promises have to go away also.

I don't have an MBA. Nate does, and I suspect Jeff Vail either has an MBA, or has courses in that direction. Not having the "proper" indoctrination can be helpful.

I DO have an earned MBA, although very old and out of date now, and certainly not of the "Masters of the Universe" [COUGH! COUGH!] variety. Being pretty much a non-comformist, I never did go in for whatever corporatist indoctrination they tried to serve up at my old B-school. Maybe that's why I've spent my career in state & local government and higher ed instead of the corporate world. I have learned quite a bit about economics, though. I think that Gail is pretty much spot on - at least as much as anyone can be when trying to get a handle on the future.

I think those graphics illustrating the difference between growing, stagnant, and declining economies are as good as anything you've done, Gail.

Unfortunately, there is apparently nobody inside the beltway that thinks that those stagnation or decline scenarios are even a possibility. Obama was pretty clearly asked about this first thing at his press conference a couple of days ago, and very clearly rejected even the possibility of long term decline. He made it clear that he is totally committed to trying to return to the growth paradigm, however impossible that may be. That is actually very bad news, because that suggests to me that Washington is going to continue doing the wrong, counterproductive things rather than trying to make the best of a bad situation, therefore guaranteeing that things are going to end up playing out much worse than they would really have to.

I think that one thing that has influenced my thinking is some of the articles I have read about Social Security and future forecasts about how it and Medicare would work. The models take into account what the world is expected to look like in the future. Tax rates depend very much on how many people one has to support the retired population, and what the total funds available will be.

When you start thinking in those terms, the standard automatic percentage increases from "growth" make a lot less sense.

Bingo! Give the man a cigar!

Irrational killer apes will continue to do what they believe worked for them in the past, even in the face of massive evidence to the contrary that such actions will work this time.

Don't be sorry Gail. Life is as it is. Countless millions will deny reality right to the edge of the cliff they'll likely be pushed off.

Odd how TOD has added to my reference frames. I've been aware of PO since the mid 80's. But what I've learned from you and others at TOD about the current economic situation has recently relegated PO concerns to lower tier.

Hey Gail,

I have an MBA that I earned in the late 90's. I initially worked in banking for about 14 months before I just couldn't take it anymore. At the time, I couldn't put my finger on what was really going on. I just knew that something was out of place. In a nutshell, all the "analysis" I performed didn't factor into any decision making processes at all. The decisions for who was going to get loans were made long before I ever got the request to analyze the company. When I would find problems with the company and their ability to pay back the loans, I was frequently ordered to change my reports. If I stuck to my guns and refused, the analysis request was given to another financial analyst and I started getting written up for stupid things like not wearing my suit jacket to the office (I carried it in over my arm) on 90° days. It was uncomfortable enough that I just found work in an entirely different industry.

I also struggled in economics classes when I was earning my MBA. I'd always seem to fall into some sort of circular logic loop when I was trying to follow the the different economic arguments. The more I pressed for explanation, the lower my grade went. The more I spouted off the verbatim answer, the higher it went. The rest of my courses weren't difficult at all. Most relied on mathematics. Economics doesn't, it relies instead on smoke and mirrors.

It took about 4 years of independent studying on the topic of Peak Oil, and our monetary system to unlearn all the BS that I was fed by the MBA program at Penn State. About the only thing that my MBA was good for was opening some doors to the various places that I applied to. It helped me to get interviews. Aside from that, the "educational knowledge" that I supposedly obtained was more of a obstacle than an asset. So your statement that, "Not having the "proper" indoctrination can be helpful" is very accurate.

TS

Hence MBA being a Masters in Bullshit Artistry - aka Con Artist. It sure as hell seems that behind every really brilliant idea (sarcasm alert) there was an MBA. I had suspicions why, but you've made it quite clear.

ToucanSanctuary, my fondlingest memory of banking was being seduced in the ledger closet. Seduced isn't quite right, because I knew perfectly well what was going on. Balancing the books, I guess. And, of course, the fact that it paid my way through college at about $100/night, 3 nights a week, in the late 70s. Can't get that now.

Changing reports, integrity. Obstacles vs assets. THAT is a whole thread. Yo Editors!

Good to hear your comments on C-Realm.

Touche Gail! Okay doomer Rockman. I think the best outcome of the enforced industrial civilisation powerdown will be the opportunity for humanity finding some humility again.

All this anthropocentric verbal brine about US, US, US! Well, I would like to serve a reminder that we are just one species in a biosphere of millions. Turn it around and look at the powerdown from, say, a whale's view. There will be less ships to collide with. Less ships looking for scientific subjects to hide from. A cleaner sea to swim in.

Seeing this to be an opportunity for our species to come into some sort of balance with the rest of the natural world brings a smile to my face.

I live in a very rural area in a third world country in South America. I live on my owned-outright nearly three acres in a straw bale house that makes it possible for me to have no heating system (a fireplace and two little woodstoves to heat 2700 sq. ft) nor even ceiling fans in a foothills location in which the temperature is in the nineties for most of the summer; winter is mild here. I grow much of my own food, drive to the nearby (12 miles or so)market town once every two weeks or so, trade produce for locally slaughtered meat and "store-bought" cheese, sometimes paying cash. Milk comes from a neighbor's cow, and eggs from the chicken coop.

Once upon a time I was a money manager in New York, an eighth-scalper in the stock market. I now live on what was the monthly condo community charge 15 years ago. The raspberries I grow here are excellent and just look at those flowers! (n.b. it's summer here) I have broadband internet (a week now), hot and cold running water, electricity and cook with gas, though sometimes with wood which comes from scrub trees on my property. I am the only English-speaker for many, many miles around, but I'm bilingual, so...

I think the above article is spot on, thought what's expressed therein when I left the US in 1998. God willing, the US will recover the sort of society it had in the 50s, when I was a boy. Less is more, small IS beautiful and the fullest satisfactions are drawn from the non-material.

It is time to Atlas-shrug off the debt and consumption society, the sooner the better, because otherwise those enmeshed in it will have to do so by default.

Chile, Argentina? No seas timido, queremos saber mas!

If we look ahead 20 or 30 years, it seems likely that the world will be very much poorer. Personal autos may be rare. Electricity may be unreliable.

Sounds like you are describing a standard of living better than the Roaring 20s, when everyone was upbeat and on top of the world.

I am sorry all of these predictions are very downbeat.

People in the past (and people like the Amish today) have been relatively happy and content with less than 1/4 of our possessions. It's all a matter of perspective; people would do well to read, "As A Man Thinketh". I realize that people who are out of work shouldn't be expected to run around laughing, but what is it that really makes a person content?

“Who is rich? He who is content with what he has." -- Talmud, Ethics of the Fathers

Hold on, this isn't correct.

The above picture (the top one) doesn't make sense.

Supply and demand are always in line. Can't be any different. What is indicated in this picture is that demand will grow at 1.8% per year, if oil stays at current price level. Well: it won't. Price of oil will go up, demand will slow.

Is that a problem? Maybe, probably not. High oil prices will force uneconomical behaviour to change. Is that good or bad?

Same people that tell me that 'there is an oil problem' also tell me that an increase in gas tax will be part of the solution. Do you see the disconnect?

It's a pity that *still* oildrum posters don't understand the basic economics. It's a real pity because as long as we keep on sending this disinformation, nothing gets solved.

For comparison: Gas is somewhere around $8/gallon in the Netherlands and no: our society still did not crash. Not even close. No tiny little collaps in a remote area either. Last summer gas wa over $10/gallon and it wasn't even mentioned on the news. Neither at the watercooler or in the newspaper. It really didn't matter much.

Lessons learned: you can live perfectly happy when gas is $8/gallon and I strongly believe that even if gas goes to $20/gallon (which it never will, because by then we would pay all our GDP to oil), life will be just fine.

Buy a bike, and a smaller car. Relocate closer to work, walk your kids to school.

Live your life, stop worrying.

Perhaps I should say quantity demanded at a constant price.

Is this even quantity demanded at current price? The historical series is based on usage at the prices that prevailed, isn't it? Isn't the series just extrapolated use based on historical trends in usage, without any adjustment for price effects?

What you are doing is merely demonstrating the disconnect between normal English and economic jargon.

No one except an enconomist would have any trouble figuring out what Gail meant. Similarly, I'm tired of being lectured that "demand is not rising, the demand curve is shifting to the right," in a situation where more people are willing to cough up more bucks for a constant supply of something. Crap. Demand is rising in that situation.

Frank, Gail,

Sorry that you are tired of being lectured about economics.

However, by being sorry, you miss the point. This is not about who speaks english an who speacs economics.

Can you do me a favor?

Please draw the demand curve over time if oil is $150 a barrel. Just like the picture above. You will see that there is an oil-glut. We will be drowning in oil. Nobody wants to buy it. If you think about it: Magically the peak oil question has disappeared by then.

I am not well-versed in economics, but I think I have pretty good common sense, and can follow an argument based on graphs.

I have a hunch that a traditional economics view that with increased price, "demand" will decrease, results in the same end-scenario that Gail describes, unless it is sprinkled generously with the fairy dust of "trust in the infinite power of technology", a belief which she effectively discredits, IMHO.

"Buy a bike and relocate close to work" is great advice. However, can the economy still grow in that manner? (It could in the 1920's but now that we are here, can we grow that way?) A bike costs, what, $100-400, to a car's several thousand dollars. Our family of 5 already possesses 8 bicycles. Trust me once I ride a bike instead of drive a car (which I did for about 20 years, BTW), I will not be going to the mall shopping for fun. I will not be buying a large variety of foods that simply are too heavy - juice, soda come to mind. My spouse or I may have to stop working, as maybe it would be hard for both of us to find appropriate work close to home.

My point is the US would be a different place, that may not grow economically - not a bad thing per se, but closer to Gail's outlook than BAU.

And as for Peak Oil, unfortunately with decreased demand, eventually we will have decreased extraction, right? The whole thing will eventually slow down to an expensive trickle. And if we can't buy ANY, because we are beat to the punch by India and China, it will be peaking for us at the rate of what we have in house.

Despite being somewhat abrasive, you have succeeded in generating a lot of interesting comments. However, it seems that you are tone-deaf in regard to US culture.

My biking friends and I frequently fantasize about the improved quality of life we could enjoy if the dominant Car-Culture of the US was dramatically reduced in favor of biking-walking, mass transit, tiny little electric cars, eco-friendly buildings, alternative energy, etc. But, it is just that – a fantasy.

The US culture is so seriously addicted to large cars that it has taken the form of a massive delusion. We will take big cars only from their “cold dead fingers”. There is simply no way for the average citizen to imagine a different culture based on a primarily non-motorized existence. Easter Island is a better analog for our culture than a Scandinavian life style.

Admonishing US citizens to emulate your lifestyle is just an exercise in self congratulation – and perhaps you deserve it – but it will have no effect here until some critical mass of people are able to see beyond their delusion. I suspect that will require much pain.

As world oil supplies decline, and especially as we see an accelerating long term decline in net oil exports, we will see a pattern of fewer consumers paying a higher unit price for a smaller volume of petroleum. For example, consumption in the Netherlands is down somewhat from 2005, but still up at about+2%/year from 1997 to 2007. About 90% of your liquids consumption is imported, so net oil imports grew at about +2.7%/year from 1997 to 2007 (EIA).

So, how does the fact that the Netherlands has so far been able to outbid some poorer consumers make the Peak Oil question go away?

Our middle case is that 10 years hence, the top five net oil exporters will have already shipped about 80% of their post-2005 cumulative net oil exports. What happens to the Netherlands economy at that point if we are correct?

Regarding supply versus price, note that the initial declines for both Texas and the North Sea corresponded to rising oil prices, i.e., falling supply in response to a higher price signal:

Supply and demand are always in line. Can't be any different. What is indicated in this picture is that demand will grow at 1.8% per year, if oil stays at current price level.

The demand curve is for EIA BAU projected demand. Anything under that curve not met by oil production is demand destruction WRT said projected demand.

Is that a problem? Maybe, probably not. High oil prices will force uneconomical behaviour to change. Is that good or bad? Same people that tell me that 'there is an oil problem' also tell me that an increase in gas tax will be part of the solution. Do you see the disconnect?

It seems clearly connected to me. Ensure high oil prices with gas tax to modify behavior.

Buy a bike, and a smaller car. Relocate closer to work, walk your kids to school.

Absolutely.

Live your life, stop worrying.

I'd say there is some need to understand the 'red sky in morning' consequences so that people don't 'set out to sea' in a BAU craft, instead charting their course with some insights about the upcoming 'weather'. And yes, live life to the fullest without assuming that consumption makes one happy.

99% of human history didn't include petroleum, but still all sorts of great philosophers, scientists, artists, poets, etc. thrived. No doubt, we can live on a much smaller energy budget.

What's harder to see is how we can manage a rapid transition without a lot of suffering. Like somebody up in a tree sawing off the limb they are sitting on - the way down can be so damaging that even the life one was leading before the climb up, that life may be difficult to recover.

Here is a simple economic model for supply and demand of a resource like petroleum:

http://peakoil.com/forums/viewtopic.php?p=608751#p608751

How could this be improved?

Why is someone who appears to claim a basic understanding of economics relying on a canard like the price of gasoline in a high taxation country to make a point?

European economies pay approximately the same price for oil and oil products as everyone else. The fuel taxes collected and distributed by governments are another matter.

Subsequent to an enormous runup in oil prices the world economy is in deep shite. It is a familiar pattern that demands analysis, expecially since there is little evidence that we can expect anything other than another run-up in oil prices if the masters of the universe manage to 'get the economy moving again'.

I am going to venture to guess that people who think increased oil prices are no problem believe that it is OK for other people to drive a lot less, but that they personally will be continuing BAU, because they can afford higher prices. I understand that some folks have already made their own transition and are living off grid, etc...

Last summer I was having a hypothetical conversation with my husband, who prefers to commute 60 miles a day to get additional training even though he is already a subspecialist, and is already employed profitably and pleasantly close to home. My question was, at what price of gasoline would this additional training become something he chooses not to do? We are well-off. We do have the illusion that we can keep our nice house, nice vacations, and endless interesting additional schooling in most "reasonable" scenarios. And it is not entirely clear (given the fact that no matter what we do, the poor "are always with us") at what point chaos among an increasing percentage of American citizens need concern us.

John Michael Greer says that even those who believe "change" is good for the Earth have a tendency to see themselves as being among the survivors. My other analogy is that of the guy who falls off a tall building, and as he passes floor after floor on his way down, he is thinking to himself "It's not that bad, so far, so good..."

Sorry Richard...an apples to oranges comparison. We don't live in the Dutch society. If gasoline goes to $8/gallon in the US and stays there it would represent a period of unprecedented unemployment in our country. Not just because driving would be expensive but it would represent a true price shock to all of our energy driven economy. Many ten's of millions with no income and a gov't so underfunded by taxes it could do little to help. Our economy has been fueled by cheap energy. Countless companies here thrive on our excessive consumption. Your country does not. Lucky for you and your countrymen. This is, of course, our own fault. We willingly allowed our hard industries to be relocated overseas so our stock holdings would grow on the back of cheap labor. Much of our economy is based upon the service industry. And these folks are much closer to the bottom of the income pyramid then most. These folks won’t be retrained as environmental engineers and solar panel designers. These are the folks who become destitute if they miss more than a couple of paychecks.

Rockman makes some good points. For generations now, we have designed our society and trillions of dollars of infrastruture around cheap oil. We are much larger geographically making it more difficult and expensive to get to work, etc. with higher oil prices. We have underinvested in local public transit, efficient rail service and compact walkable communities. We are now experiencing and will be for a while the impacts of just a brief period of higher oil prices and it has disrupted our entire society. I could go on and on about the differences between our two societies and they are significant.

I just wanted to give kudos to ROCKMAN for pointing out that $8/gallon in US is not the same as $8/gallon in another context like EU. The structure of the economy, where the industry is, all that matters. $8/gallon in EU is maybe lifestyle equivalent to $4/gallon in U.S. A few parked tankers away.

cfm in Gray, ME

Not true. A perfect example was the Southeast USA following the hurricanes last fall. The supply of gasoline in many areas (Tennessee, Geogia) was significantly lower. The demand was significantly higher -people drove as far as 50 miles to wait in line and get gas yet were often unable to find any. Because of fear of retribution from angry customers many gas station owners requested smaller or no shipments of gas and just covered their pumps so as to avoid the risk. In this and similar situations, supply equals product sold, but is much less than demand because there is not one clearing price - the decision to 'play' the game reduced supply.

In a broader sense there are MANY things that you cannot put a pricetag on. Im sure you can see how supply and demand might not apply to ecosystems, old growth forests, or love, etc.

Nate,

Your comment about supply and demand is valid short term. Probably the best example is an electricity demand spike exceeding the grid capacity. The result is rolling blackouts. Longer term( 5-10years) this can be corrected by building more generating capacity or improving the grid.

The difference with oil is that adding more capacity(oil wells) doesn't give more supply because of declining reserve quality. In this sense oil is different from most other energy resources, and nearly all mineral resources. Long term, this is going to lead to direct forced demand reduction( destruction) for oil.

Where Gail's post is going overboard is to extrapolate "declining oil" to "no oil" or worse "no energy", because other energy resources use oil to some extent. If we are facing NO OIL within decades, what Gail is saying; massive collapse in economic activity would be expected. If we are facing 10%-50% of today's oil supply in 20-30years energy supply can be maintained by resource substitution.

The only long term secondary impact that I can see from greatly reduced oil will be greatly reduced air travel. Declining natural gas will have wider impacts, especially chemical feed-stocks for plastics, although many of these can be generated from coal, providing we stop burning it.

Weird, that makes no sense for me.

Richard, there is currently a strong correlation between oil consumption and the world economy:

The above data comes from "Mitigation of Maximum World Oil Production:Shortage Scenarios, Hirsch, 2008."

I have a brief write-up here:

Estimating the Economic Impacts of Oil

http://www.postpeakliving.com/blog/aangel/estimating-economic-impacts-pe...

Since it would take years for us to move off of oil in any substantial way (see http://www.energybulletin.net/node/4638), we can expect the world economy to decline as oil availability declines. Thus, a likely scenario for our economic future looks like a staircase in which we descend a step each time oil increases in price like it did last summer:

I expect the next price increase will kill the auto and airline companies, which are zombies right now.

-André

http://www.energybulletin.net/node/22775

Archived Nov 23 2006

As Fuel Prices Soar, A Country Unravels

Gail,

An I haven't got much time, and in fact, have not read but maybe 1/5th of the article. 2 boys and a wife have my ADD head in a hurry. But more important than reading the rest at this moment is thanking you for another excellent, well thought out argument. You are truly "fight[ing] the good fight".

"You go girl!"

strav

Does anyone else have "preview" in the box where "post" should be? It actually kept me from sending my last post, cuz I was confused. and thanks to the folx working on the new EROEI oil drum page (westexas is it all your work? I can't remember). I am looking forward to learning more about EROEI. I think this particular part is going to make all the difference in this case (it is the only part of the equation that is left for mechanics to dictate... the only other part is the statistics of the Hubbard's curve, and lets hope we get lucky on this one.......).

Not, for you grammarethtarians, said as that one, as it is still left to be decided.

Nothing is set in stone,

stravasso? (picasso's portrait of igor stravinsky set live and in living action by a hyperactive imagination?)

(really i truly appreciate it)

peace.

strav,

I'm not involved at all in the EROEI work. One obsession at a time is enough for me (net oil exports).

When we try to find alternatives, we encounter limitations of other types. In some situations, natural gas might be a substitute, but in North America it is also in relatively short supply. Coal is in better supply, but it has serious climate change issues.

I agree with this, but climate change issues won't stop the displacement of oil (and gas) to coal. The people who control the coal are not Bangladeshis or Maldeve Islanders, and will give this concern short shrift. Here in the UK most people have not changed their behaviour - CC is still perceived as a theoretical, or someone else's, problem. When oil reaches $200 the economy won't stop, it will keep on trying to grow until the last blade of grass turns brown. In my opinion, in 20 years time the 'first world' will be financially richer but the environment will be a mess.

Andrew

Nice job Gail. I commend your willingness to stick your neck out and predict consequences which are closely congruent with our world 12 months later. Your ability to express yourself clearly is a gift and it is a pleasure to read about economics and energy from someone who is so knowledgeable in both fields who has no specialized professional training in either. The current global economic depression will be changing the discussion at TOD. It appears that that the back side of the curve will ease for a while. If this steep economic delamination continues for a decade or two, the world will need less and consume less and I think from a peak oil standpoint, the collapse may be gradual and despite increasing world poverty we will have more time to adapt to our finite world. If by some Deus Ex Machina event the world economy recovers and demand spurts, volatility will return and we will be repeating all the fun and of the past 9 months.

Glad you like my post!

While I don't have the standard MBA background, I do have an actuarial background. This is more of a math / finance background, particularly focused on insurance companies. I have been working with financial statements of insurance companies for years, and making projections of various kinds, so I am familiar with a lot of the financial world, if not all of the popular theories being promulgated in business schools. I also have had first-hand experience on what goes wrong with projections, and how companies can get into financial trouble. One of my prior employers went bankrupt after the oil price spike in 1974, and another one almost did.

I read Benoit Mandelbrot's "Misbehavior of Markets" back when it first came out in hardcover several years ago (2005?). More recently, others seem to be getting on the bandwagon with Taleb's "The Black Swan" and "Fooled by Randomness".

After people have been trained in the MBA way of thinking, I am not certain they are as aware of what the real problems are.

Some Questions:

We only pay about 4% of the US gross domestic product for it(OIL).

How much of GDP goes for all energy?

Can 1/(fraction of GDP spent on energy) be used to approximate the EROEI of our economy?

Of course.

It's called energy intensity, EI.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_energy_intensity

First you have to guesstimate what the cost of energy.

In the US almost all energy comes in the form of mainly oil 39% or electricity 41%. Coal, natural gas, nuke etc. are mainly indirect inputs to consumers. Oil costs maybe $50 per boe while electricity costs about $150. Assuming 50-50 split, an average cost would be ~$100 per boe.

EROI= $1000000 of GDP/($100 x EI x 7.33)

=eo/einv

For the US at 220 toe per $1M of GDP

you get an EROI of 6.2.

For Japan at 154 toe per $1M you get an EROI of 8.9

For Canada at 293 you get an EROI of 4.65

For Russia at 519 you get an EROI of 2.62.

Very interesting number majorian. Mucho thanks. Especially how low Russia appears to be. I knew there was a good reason why I continued to read your usually weird comments.

XOXOX

All energy producers look highly inefficient.It's probably due to the large investments required to make energy.

It is unlikely that any energy producer, which feeds energy consumers

will have a low level of energy intensity.

Given FF depletion it seems that energy investment will fall and reduce the worlds energy intensity.

It is likely that there is some minimum energy intensity level. Bangladesh which seems always on the edge of dissolving has an energy intensity of 97 toe per $1M.

Overall the world needs ~200 toe per $1000000 on average but energy production is limited to only a few countries.