Sustainability, Energy, and Health

Posted by Gail the Actuary on December 7, 2008 - 10:50am

This is a guest post by Hank Weiss of the University of Pittsburgh. Hank is an affiliate of Dan Bednarz, and was instrumental in setting up Health After Oil, where this article was previously published.

The U.S. presently spends an estimated 16 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health care, compared with 8 to 10 percent in most other major industrialized nations. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) projects that growth in health spending should continue to outpace GDP over the next 10 years [The Commonwealth Fund, January 2007]. But can this really happen in an era of energy and resource limitations? What are the ramifications to health care and sustainability if it cannot?

From an energy perspective, health care buildings account for 11 percent of all commercial energy consumption, using a total of 561 trillion Btu’s of combined site electricity, natural gas, fuel oil, and steam or hot water.[EIA] Health care facilities are the fourth highest consumer of total energy of all building types and have an energy intensity (Btu/square foot) that is the second highest among all commercial building types.[EIA] Many medical products, few of which are designed to be recycled, are petroleum based; including gloves, syringes, IV and dialysis tubing, tablets, gels, ointments, antihistamines, and many antibiotics and antibacterial medications. None of these energy estimates accounts for the huge energy and material costs for the manufacture and transportation of goods, services, personnel and patients that enable these energy intensive facilities to perform their myriad and complex functions.

In the United Kingdom it has been estimated that as much as 5% of all transport need is generated by the National Health Service.[1] In 2001 the U.S. National Household Transportation survey reported that on average, each U.S. household makes about one trip a week for medical or dental visits and that each trip is about 10 miles in length [personal communication, Center for Transportation Analysis, Oak Ridge National Laboratory]. While this represents only 1.2% of all vehicle miles traveled it does not include the miles traveled by medical staff to work nor doctor related travel by public vehicles, nor travel by the staff, support services and vendors that keep modern medical systems functioning.

With healthcare costs already growing exponentially from the demand for more and more complex services and drugs, compounded by; 1) inflationary increases due to the sectors heavy use of energy and transportation, 2) a rapidly aging population needing greatly increased services, 3) a falling proportion of workers to support the retired population, 4) 45.7 million uninsured and increasing poverty [Income Poverty and Health Insurance in the US: 2007], 5) increases in lifestyle caused diseases, 6) decreasing public health expenditures as a proportion of federal health dollars (see figure 1), 7) a growing reverse “brain drain” to oil wealthy countries, then throw in energy and economic declines - we face an almost unimaginable crisis in health care funding and delivery that will make today’s debate over who pays for the uninsured quite moot. It is very difficult to foresee how the current U.S. health care system can survive the confluence of all these pressures for increasing services at increasing costs at a time of decreasing resources. We must soon decide, even more so than is done today (either implicitly or explicitly), who will get what kinds of services and who will not.

Figure 1. Source: University of Illinois.

The challenge is how do we construct a much lower energy health system without major negative impacts on health status? The “Peak Health” crisis will likely bring government deeper into paying and managing this large sector of the economy as many private health care providers fail to adopt or go broke trying. It may even be the driving force that eventually leads to a true universal health system; a model many other industrial democracies have used for a long time. But it is not yet clear what that future U.S. health system will look like in different phases of the transition; though there are many examples of less energy intensive medical care systems to choose from (see below).

While some observers have suggested alternative health care modalities may come to the fore or that a much greater focus on prevention and community level primary care will be necessary[2], in all likelihood what will emerge will be something different from anything we see today. Parts may be familiar though; borrowing and melding what can work from many traditions while building upon elements of modern medicine that can make the transition. It is hoped that whatever form(s) of health care do emerge are built upon a perspective of evidence-based preventive measures and treatment so that we don’t move to something novel or trendy just because we hope it will work. But clearly, believing that all of the best available disease care can be affordably provided to every person is a pipe dream policy doomed to failure in an era of resource and energy limitations and one that we can already begin to see in the failures of growing costs, large numbers of uninsured, and pockets of increased health disparities between rich and poor.

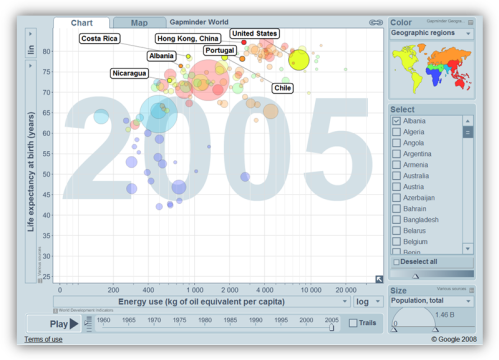

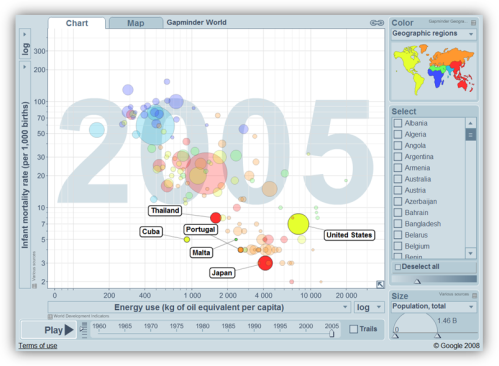

The fundamental positive relationship between energy use and health status is not well appreciated; overshadowed usually by a focus on the direct and positive wealth and health relationships (Wealth = Health) discussed recently by Hanlon and McCarteny and many others.[3] But from an energy perspective, we know that Energy = Wealth; therefore to a great extent, Energy = Health. This is demonstrated by plotting per capita energy use against the key public health indicators of longevity and infant mortality.

Striking associations are evident for each (see figures 2 and 3 below). Yet there are nation specific exceptions along these continuums that may offer insights as to how positive public health indicators can be maintained at very favorable levels with considerably less energy input. This opens up the vital need to define how this is done and which of these may be imported to the U.S. in part or in whole to reduce health energy and resource expenditures while maintaining high public health indicators.

Figure 2. Selected countries with life expectancy at or above US levels with much lower national energy use (source, Gapminder).

Figure 3. Selected countries with infant mortality rates at or below US levels with much lower national energy use (source, Gapminder).

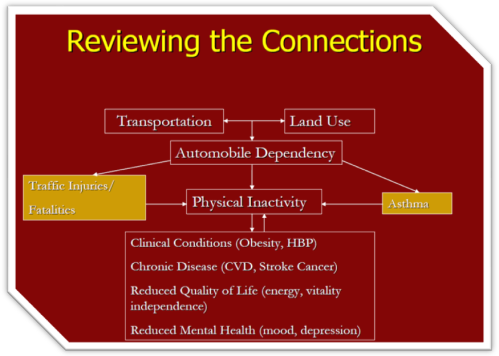

The relationship between sustainability and health can also be explored through the interaction of the built environment and land use on health. Looking at the picture this way suggests areas of potential gains in preventing injuries and many “lifestyle” diseases (see Fig 4 below). But there remain potential risks to health from sustainability lifestyles that are not often considered. Transitioning to sustainable living requires changes in lifestyles with attendant increased and decreased health risks.

Figure 4. Original source: Active Living by Design, University of North Carolina.

Planning for and managing these risks will be a critical aspect of moving to sustainable economies and environments. Examples of increased or potential risks already of concern with increased energy costs include pedestrian and bicycle injury, scooter and motorcycle injuries, as well as things like gardening injuries (as people grow their own), wood chopping related injuries (as people in NE switch from fuel oil), and fires (due to gas hoarding, emergency use of space heaters and wood stoves). Also there are concerns (documented in some similar economically distressed settings) over increased violence and suicides due to job losses and increasingly difficult economic circumstances, especially for those already living on the economic edge. Mental and behavioral health issues will be important concerns in the transition to sustainable communities.

All too often, sustainability plans and efforts do not include health expertise or health planning input, components and considerations, yet health status is consistently among peoples most important concerns. If we cannot ensure and document adequate health status and care in the emerging efforts at sustainable environments, communities and lifestyles, we will lose a fundamentally important incentive for individuals and governments to adopt them.

[1] Material Health: A mass balance and ecological footprint analysis of the NHS in England and Wales, Best Foot Forward Ltd, 2004.

[2] Jeffery, Stuart. How peak oil will affect health care. Published Jun 16, 2008, The International Journal of Cuban Studies.

[3] Hanlon, P. and G. McCartney, Peak oil: Will it be public health’s greatest challenge? Public Health, 2008. 122(7): p. 647-52.

Hi TODers! Check out my latest video! http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zv_UMzqgehE

Excellent video Kriscan.

You "get it" - exactly.

Doktor_Nik2

here is a nifty site for getting historical heating degree days. you can find a weather station near you, and plug in any temperature(thermostat setting). they ask users to spread the word:

http://www.degreedays.net/#generate

i have found the doe and noaa sites to be cumbersome.

Our basic health in some ways might actually improve if our high-energy health care system collapsed and had to be reformulated as a consequence of peak oil. There are some aspects of our high-energy society which actually make health worse. I don't want to argue that things will be better after the collapse of our high-energy civilization, because I don't know and can't imagine all the details of how a future health-care system would work. But what I would argue is that it will not necessarily be as bad as it seems at first glance, and that there is a potential for it actually being better. I'd like to see this explored.

There are two prominent examples of health improving in the face of a declining standard of living: Denmark in World War I, and Norway in the World War II. Denmark (though neutral) was subjected to the Allied blockade of the continent. The entire country was put on a lacto-vegetarian diet. Death rates dropped by 30%. Norway, occupied by the Nazis, also saw its deaths due to circulatory diseases drop dramatically. In both cases, when the war ended, people resumed eating their normal diet and the death rate went back up.

Health care is heavily commoditized, and in such an economy things that relate to health that can be turned into commodities (e. g. pills) receive a lot of public and private attention and lots of money and research. But things that are less easily commoditizable, such as relationships, information, good nutrition, exercise, etc., receive less public and private attention or none at all. Other industries, such as the food industry, may actually be selling commodities that are bad for health. In this connection the book by "Privileged Goods" by Jack Manno, an ecological economist, is very helpful.

Even if a magic wand were to eliminate both peak oil and global warming and other natural resource constraints on our economy, we'd still face a health care crisis because of the above problems. I'd suggest that this is because the health care system is oriented towards selling products and not on diagnosing relationships (e. g. between food and health).

If we are going to look realistically at what will or could happen to health care in the face of peak oil, we need to say something about what is making people sick and what we can do about it. I don't see any analysis of this. Why are people in the U. S. having heart disease, cancer, diabetes, obesity, kidney disease, etc.? These are "diseases of civilization" which are not present in the "less developed" nations of the world to nearly the same extent -- and much of this is because they don't have our "civilized" diet.

There are also the new deadly infectious diseases, such as antibiotic resistant tuberculosis, mad cow, avian flu, etc. -- where did these come from? A lot of the health problems we have stem precisely from our commodity-oriented food and health care system. Modern factory farms have become breeding grounds for many of these diseases -- most antibiotics are being administered to animals in the U. S., for example, making factory farms breeding grounds for antibiotic-resistant disease. Both the 1918 flu epidemic and the H5N1 avian flu virus came from birds.

In order to realistically assess what problems we will have with health after peak oil, we need to look at the actual health problems that we face. Most of our heavy, heavy medical expenses in the U. S. go to problems that our civilization is actually creating (high-fat diets, factory farms, antibiotic resistant bacteria). We need to look at what health is before we can assess what health care should be, rather than just accepting such problems as antibiotic-resistant tuberculosis and heart bypass surgery as givens.

Keith

vtpeaknk started this related thread in yesterday's Drumbeat. Yet Heinberg in his discussion with Caldicott (toplinked in that Drumbeat) talked about the need to keep fuel for emergency vehicles. How that would work when the roads and bridges are a mess is beyond me.

One of the biggest policy disasters of past 70 years or so has been the defunding of public health. Tainter points out how the bulk of health improvements came from public health. Now all the money is going into private health. But public health, conceived broadly, is clean water, clean fish, clean air, everything from environment to economic injustice.

In our current economic crisis, Main Street businesses and local and state governments are crashing. They are going to take out the health care system when they go. PEBO's current response is endless money for the bankers and - to save a few billion dollars - digitizing health care records. [Not only is it unlikely to save any money, but there are all the questions about increasing complexity - bad, bad, bad idea.] Rather than bailing out all the banks, businesses and states and leaving the rotten structure in place a better idea would be to take over the disease care industry/insurance and reshape it into community based public health. We used to have something a little like that, BTW, the old Blues; they had special, community based non-profit charters. [And as such could not compete profitably in Reagan world.] We need to go well beyond the old Blue Cross model.

I'd think that moving to a public health model - with minimum "police" costs, in the terms Peter Drucker would have used - would be much better. Monitoring everything increases transaction costs and creates all sorts of barriers on class and income lines - just when we want to emphasize "we're all in this together". My biggest take-away from "Power of Community" was how Cuba (apparently) framed their "Special Period" as a public health crisis. "Penicillin not paint" was the slogan if my memory is correct.

Contrast that to US, where the public health slogan is "Guns before penicillin". NOLA. How many state EMAs are under military control? Tell me that the planned response to an epidemic is not a roadblock at the corner? That's what it is here in Maine, according to a MEMA mucky-muck I cornered on the topic. I don't call that public health.

HT for most of my thinking on this to Peter Montague of Rachel's.

cfm in Gray, ME

Excellent points Keith. Much of the food we eat is not food but food stuffs. It's prepared in a factory & shipped across the country to us. Few people actually have the skills to even cook now. Higher energy costs will force people to return to a more simple diet made by them, not made by Kraft.

I lived for 6 years without a car & during that time my health was better than it's ever been. Part of the reason was because I had to walk places, the other reason was that fast food is built around car access. No car, limited access = better health.

Norway under the nazis was effectively put on an "anti-Atkins" diet: Very little fat, but enough carbohydrates. "Fat hunger" is a phenomenon known to many old people, and whatever temporary advantages you'd get from turnip steak, you'd probably lose from the craving for fatty foods you aquired when they were scarce.

A far more important factor was that tobacco was in short supply, and alcohol consumption at an all-time low. A prominent alcohol researcher in Norway has commented that today, we pay ourselves out of our alcohol problems with expensive treatment facilities and social services to take care of injuries, neglected children, traffic accidents and all the other unpleasant side-effects. A hundred years ago, that was not an affordable option, so there was a strong social movement to resist and restrict alcohol instead (Teetotalism).

I think that in the current depression/long emergency, how our societies deal with alcohol will matter a lot. Will we do as countless tribal people have done when encountering new, unpleasant realities - try to drink ourselves out of our sorrows? Or will we do as the Sami did after Læstadius, harden ourselves against destructive influences, and purge our culture of the traditions which we don't see a use for in the new reality?

There's no question in my mind that alcohol is a significant health problem. However, it appears that in terms of what was studied in Norway (circulatory diseases, as I recall), alcohol may actually have had a slightly beneficial effect, because alcohol would presumably make heart attacks less likely and produces a mild elevation in HDL. On the other hand, excessive drinking raises the risk of strokes and non-circulatory diseases such as breast cancer. I'm not prepared to argue that the effect of alcohol on circulatory disease in Norway was a "wash," but I think alcohol was at least likely not the only factor. There are enough other problems with alcohol to justify minimizing or eliminating alcohol in one's diet.

There are a lot of complicated interactions here because the "civilized diet" typically has a lot of things wrong with it and it's often hard to tease out what exactly is causing the problems. So I'd be happy to just say that refined carbohydrates, meat consumption, and alcohol are all significant health problems. The important point is that diet has important effects on disease, and post-peak the decline of this "industrialized" diet may have significant health benefits.

There is also the point that factory farms have significant negative public health effects independent of actually eating the stuff they produce. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and avian flu, are being promoted largely through the excess use of antibiotics in factory farms in the U. S. and elsewhere. I understand the EU now prohibits the routine use of antibiotics to promote growth, I'm not sure how this is working or how much it has resulted in a decline in the use of antibiotics (are they just getting around this by justifying antibiotics for disease control, for example?). If H5N1 virus were to become contagious among humans, you might have to go back to the 14th century to find a historical precedent. So if post-peak the factory farming system were to collapse, you'd see less meat eating anyway, but that would probably have a beneficial health effect overall.

Keith

Nonsense! Avian flu has absolutely nothing to do with antibiotic use (or abuse). I was in agreement with you until you said that.

Agreed. I should have said something like, "antibiotic-resistant bacteria and avian flu are being promoted largely through the excess use of antibiotics in factory farms on the one hand, and by factory-farmed birds generally on the other." Flu is a virus, not a bacterium.

Very sensible comments,Keith.Same problems here in Australia although we do have a universal health care system which is well over the limits of it's capacity.There is a parallel private system which costs.

I can't see the present system surviving intact the downsizing of the economy.That may,in fact,be a good thing as there may be more effort put into preventative measures,such as diet(more vegetarian).

The public health issues remain - clean water,clean food,clean air,protection from epidemic disease etc.

But most of the money spent on the health care system could be gradually reduced by social change and that is always difficult to do voluntarily.

I suspect that circumstances will force many changes,hopefully in the right direction.

Despite the odd blunder (above) about abuse of anti-biotics the tenor of comments on this useful post (thanks Gail) concerning public health and dietary and exercise and other social patterns, are all in the right direction.

The 'advanced' urban world has done well enough with vaccination and infectious disease control, infant mortality and malnutrition and death during child-birth, and very badly compared with some traditional agrarian cultures for chronic disease in mid to late life. The huge 'hi-tec' health care burden is largely a result of these chronic diseases in 'western' and OECD countries and their recent epidemic increase in 'transition' economies. (Try google 'diseases of transition'.)

However:

1. Recent smoking cessation among middle aged is calculated to have contributed half (50%) of the halving of age-weighted incidence of cardiac deaths in UK over a 20 year period. (Parts of UK still show world record incidence of cardiac morbidity.)

2. Massive difference exists in age-weighted incidence in important cancers between OECD countries and for example Bangladesh or Sri Lanka. Colerectal and prostate cancer for example are order of magnitude more prevalent in OECD. Do not want to frighten any Australians, but check out definitive database GLOBOCAN for prostate cancer.

3. Recent large meta-study seems not only to confirm that the degree of compliance with a defined version of so-called Mediterranean Diet is cardio-protective, but higher compliance makes a surprisingly favorable difference to onset of both Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

4. I personally have reduced weight and kept it low (mild calories restriction) using a 'traditional' Med Diet, heavily skewed to 'non-dairy' vegetarian, with daily exercise for two decades following heart attacks at a relatively young age. Apparently my 'markers' and general fitness reflect the benefits - can still do half-marathons. Hope though that my low dose statin (only widely available in UK for last decade) will still be available - but generic versions are very low cost and adequate if quality control procedures are tight enough.

One on-going study of interest in this context may be the work of calerie, a "Comprehensive Assessment of Long-term Effects of Reducing Intake of Energy," or (moderate) calorie restriction. My own decision to participate in the study came by way of my reading on energy and the environment. Being a guinea pig hasn't been the easiest thing to do -- in my experience, recording the data consistently has been a bigger challenge than the carlorie restriction itself -- but it's been interesting at a personal level and in any event satisfying to know that the data will contribute to a better understanding of the long-term effects of diet / calorie restriction on health.

The December 11th episode of David Suzuki's The Nature of Things looks to Europe for evidence of sustainable development. You can view the entire show at:

http://www.cbc.ca/documentaries/natureofthings/2008/suzukidiaries/

Cheers,

Paul

I'm not sure how much credibility Suzuki has when talking about sustainable development given his stubborn opposition to nuclear power. The end result of such policy promotion has allways served to increase the capacity of coal.

http://www.davidsuzuki.org/Climate_Change/Energy/Nuclear.asp

One of the core tenets of sustainability is to not produce long lived toxic substances that build up over decades faster than they can be converted into non-toxic substances. So there is no contradiction in his position.

He is arguing we use wind and natural gas instead (not coal).

One of the core tenets of sustainability is to not produce long lived toxic substances that build up over decades faster than they can be converted into non-toxic substances. So there is no contradiction in his position.

The core tenet of sustainability is no opulation growth. What has Suzuki proposed to stop population growth in Canada?

Canada's fertility rate of 1.7 births per woman is already well below replacemnt.

First, for a country like Canada that has immigration, just giving a figure for birth rate, is obviously incorrect. Second, per this info,

http://geography.about.com/od/populationgeography/a/populationgrow.htm

Canada is not even at replacement level regarding birth rate. It says the growth rate is .3% internally, and .6 from immigration, given a total population growth rate of .9%. Now the population pollyannas will say - "But that means Canada won't double in population for 77 years". But however much you want to ignore or poo poo population growth, it is not sustainable. So if sustainability is coming out of one side of your mouth, population control better be coming out of the other. But even more shocking, it brings no benefits to the majority. It's major benefit is to landowners and developers (and the politicians they choose to bribe) who get to reap the gains that population growth brings to land prices and the demand it creates for new construction. Yet the negatives of population growth fall on everyone. The overcrowding, traffic congestion, pollution, wage depression, resource depletion, resource price increases and others. It continues to amaze me how everywhere - save some rich enclaves - they let population growth continue to ruin things, and yet the people in all these places all shrug and sigh and say "well, that's progress. you can't do anything about it."

Until governments begin to remove it, CO2 from natural gas burning is indeed building up faster than it is being converted into relatively non-toxic substances such as bicarbonate.

The noted shill has recently said,

... as if continuing to rely on nuclear fuels, in which his behaviour would suggest he has no financial interest, were not entirely different in all the mentioned respects from continuing to rely on much more costly, much more tax-lucrative fossil fuels, tax lucre that he lives off.

--- G.R.L. Cowan (How fire can be tamed)

Hi Dezakin,

Personally, I don't consider Dr. Suzuki's credibility to be diminished in any way because of this, and in the context of Canada's somewhat chequered experience with its CANDU reactors, one might reasonably look to other alternatives such as industrial co-generation, district heating, wind, small hydro, biomass and so on. In addition, we Canadians waste enormous amounts of electricity and have done relatively little to address this; let's at least try to make better use of what we already have before embarking on an expensive campaign to add new capacity.

Cheers,

Paul

Please people, when discussion wind generation, stop comparing 1 kw installed wind capacity to 1 kw installed capacity of any other source. They are NOT equivalent, and if you don't know what the actual equivalence ration for useful estimating is, you're not qualified to be in the discussion.

Hi lengould,

Did I make such a claim?

Cheers,

Paul

Implied.

Then, with all due respect, you read more into my statement than intended. Each of the alternatives I noted will have their individual availability and capacity factors. Of Ontario's twenty nuclear reactors, sixteen are currently operational, two will not return to service due to their poor economic performance (Pickering A's Units 2 and 3) and two more will be offline until 2009/2010 due to multi-billion dollar refurbishments (Bruce A's Units 1 and 2). Note that Pickering A and Bruce A's capacity factors for the period spanning 1997 to 2003 is as follows:

Pickering A

Unit 1 - 87.97%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%

Unit 2 - 64.23%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%

Unit 3 - 65.34%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%

Unit 4 - 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 18.88%

Bruce A

Unit 1 - 20.57%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%

Unit 2 - 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%

Unit 3 - 57.24%, 85.6%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%

Unit 4 - 39.9%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 0%, 13.83%

Cheers,

Paul

Interesting article. Thank you.

Do you mean adapt?

Clearly, more walking improves health and reduces weight. One of the best things we could do to improve health would be to reduce dependence upon the auto. In addition, the decreased air pollution and all the other negative effects of fossil fuel production would be reduced. While I would prefer auto use be decreased in general, even electric autos would at least decrease pollution at the point of use.

Living in the city, getting rid of my car caused me to change my lifestyle in such a way that my health dramatically improved.

And what about the stress, not to mention potential death, of not having health insurance? Even with health insurance, there is also the stress of paying the premiums, the copays, and the deductibles, not to mention the stress of having to hassle with the health insurance companies.

Moving to a government run single payer system could potentially have positive impacts on sustainability and the toxicity of facilities. The government could not only have an influence of the prices charged but the energy efficiency of the facilities themselves.

Building future health facilities to high LEED standards will improve the health of those working in and visiting the facilities. Currently, visiting most health facilities by the chemically sensitive is a dangerous activity.

Absolutely. I'm just short of 68. I have a car, parked 4 or 5 blocks away. Sometimes the battery discharges because I haven't turned it over in a week or more. I think nothing of walking 5 miles. 10 miles and my legs are a little stiff the next day. I live in Jersey City, polluted. While pollution is not good, even worse, I would say much worse, is not walking.

And yes, it's absolutely nuts not to have national health insurance, single payer system for every one. Basic care, not cosmetics. And it should be localized as much as possible, not centralized except for that which must be. And it should focus on prevention, healthy life styles, starting in schools.

And of course, the biggest thing is to have basic economic security for everyone -- you may not have an SUV and HD tv, but you have a job, a roof, meals, school for your kids. And you have to stop wanting all the crap beyond that. Then the worry is gone, the stress is gone. But this will take a gigantic transformation in our whole way of life, value system, and social system -- a revolution.

And we might have to be willing to learn from others -- like Cuba even, not that things are anywhere near ideal there (or anywhere else). But they seem to know how to do a lot more with a lot less, at least in the health care area.

Paradoxically, if it were handled right, and it won't be, retrenchment could lead to a lot healthier society.

Yet another issue is extreme specialization. The localized care has to be supplied by GPs. The GPs should have access to specialist advisers, but they should not be sending one off to these guys except in the extreme cases. Same thing with PAs. More use could be made, house visits where needed, but with supervising MDs.

Liability system is totally nuts. Should be shut down. If a doctor is grossly negligent, then their license should be suspended or revoked. It should not be converted into a money issue. Reasonable errors cannot be punished.

Could go on and on, but won't.

Excellent post. Deserves widest possible repetition.

I think that one of the first health care services to suffer during a period of increasingly scarce and expensive energy will be those related to home care, such as visiting nurses for invalids, hospice programs, and the like. Visiting registered nurses and nurses aids put a tremendous amount of mileage on their cars, and the mileage reimbursements have not (until the recent sharp drop in gasoline prices) been keeping up with costs.

If there are outright gas shortages, many bed-ridden people under home care may find themselves stranded for days at a time, though one would hope there would be emergency gas allocations for home-care providers. It still could get sticky, though.

I wouldn't worry too much about the production of pharmaceuticals, largely because the raw material input is typically a very small fraction of the production cost and final selling price.

"If there are outright gas shortages, many bed-ridden people under home care may find themselves stranded for days at a time, though one would hope there would be emergency gas allocations for home-care providers. It still could get sticky, though"

In Canada (in AB - the land of 'Health Care bliss' .. ) we have similar problems - but with very different proximate causes.

So far (not energy related yet) our 'exemplary' socialized health care system - is arguably good and very economical (despite the waiting times), .. but only just.

(It's difficult to fathom the American system of Health Care, except maybe thru the County Hospital system).

The intent of our paymaster (the AB Provincial Government in this case) is what now, counts.

In this jurisdiction, and, in many others in Canada; AB (ie the AB government) seems to 'lead the way'.

Sure enough, what was once a good thing for doctor and more specifically for _any_ patient some 18 to 20 yrs ago, no longer seems to apply. Thanks be to the Provincial governing powers that have existed in the recent past - and that currently exist.

Now, any Provincial Government has (almost) complete control over fees payable to Docs and to Hospitals. And, very significantly, they also now have the power to grant a license to (-any-) physician to Practice Medicine within various jurisdictions in Canada.

This latter government 'power grab' is of particular concern to those physicians who have trained in Canada and written qualifying exams of the country or of the province. (similar to American exams & qualification to practice in a State)

This power was previously the jurisdiction (only) of the 'College of Physicians and Surgeons' of the various provinces in Canada, not so very long ago. These 'colleges' were invariably staffed by Physicians .. with a world of experience behind them. - Now they are legally under the jurisdiction of the various provincial governments.

I would wager gas shortages and even the concept of Peak Oil are not even on the radar screen for the vast majority of Canadian docs, and the various provincial governments. - And especially the Federal government of Canada.

RE the post WWII examples of Denmark & Norway.

It would be interesting to see if there is data taking a closer look at the dietary changes that actually correlated with the rise in mortality. Most people would make the assumption that an increase in meat consumption was the culprit. It may well be that it was an increase in sugar and refined carbs that was the problem.

Altogether, the diet issue looms very large in the future of health care and it is important that we find out if indeed the low fat/high carb paradigm is seriously flawed as recent reviews suggest.

If you're interested, the original article on the case in Denmark by Mikkel Hindhede can be found in the Journal of the American Medical Association, 7 February 1920, "The Effect of Food Restriction During War on Mortality in Copenhagen."

It's clear to me that sugar and refined carbohydrates are part of the problem. However, meat and animal products are also implicated, as has been made clear by the numerous problems with the Atkins diet (a high-protein, typically high-meat, diet which corrects the refined carbs problem but not the meat). Briefly, the Atkins diet seems to help people lose weight by becoming sicker. I'd be interested in any studies showing that the "low fat/high carb paradigm is seriously flawed." While I haven't followed this issue closely, my impression is that there have been repeated and usually ideological attempts to dismiss the low fat/high carb diet, and so far I haven't been impressed. E. g. they present diets that are 30% fat as "low-fat," or high sugar diets as typical of high carbohydrate diets, etc.

There are some issues that haven't been resolved here. Some fats, like trans fats, seem to be worse than others, and sometimes people have specific problems with carbohydrates in wheat, corn, or dairy. But overall I think it would be really hard, after impartially looking at all the evidence, to make a case on health grounds for more than very limited meat consumption.

Keith

The Atkins diet is very healthy if you avoid the beef and pork (stick to chicken and fish).

And this must also assume similar avoidance/reduction of other saturated fats from animals, such as cheese, etc. Has anyone seen anything substantive (i.e., medical peer-reviewed paper) on this?

Support for the Atkins diet relies exclusively, as far as I can see, on anecdotal evidence, and the scientific studies are rather unanimous that it is ineffective. This diet is condemned by almost all the experts who've looked into it, and the people who have spoken out against it are virtually a who's who of nutrition science: the American Medical Association, the chair of the Harvard's Nutrition Dept. in 1973 (Frederick Stare), former surgeon general Everett Koop, etc. etc. etc. I would recommend the book "Carbophobia" by Dr. Michael Greger, or check out http://www.atkinsexposed.org/.

There is short-term weight loss, but the induced ketosis is dangerous and it is almost impossible to keep the weight off in the long term. One long-term study comparing the Zone, Weight Watchers, Ornish, and Atkins diet showed the Atkins diet in last place. The low-fat, low or no-sugar, high-complex-carbohydrate Ornish diet appeared most effective. [ Dansinger, M.L., Gleason, J. L., Griffith, J.L., et al., "One Year Effectiveness of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone Diets in Decreasing Body Weight and Heart Disease Risk," Presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions November 12, 2003 in Orlando, Florida, as cited on AtkinsExposed.org.]

The Atkins diet has killed at least one teenage girl trying to lose weight, Rachel Huskey, who experimented with the diet because among other things boys were teasing her for being fat. Although her heart was otherwise healthy, evidently an electrolyte imbalance led to an irregular heartbeat and a collapse. If you are very careful you may be able to do Atkins safely, but I believe that impartial examination of all the evidence will show that it is both dangerous and ineffective. I would urge everyone to avoid the Atkins diet and consider the other alternatives.

Keith

I've dropped about 15 pounds on an Atkins-like diet in the last month or so. I've also gotten rid of a problem with falling asleep during the afternoon, which I can reproduce reliably by eating carbs.

I'm adding unrefined grains and veggies, but I'm still protein-heavy and achieving good results.

Britain had a similar phenomenon during the war. Food was severely restricted and the general health of the population improved. I don't know about how alcohol figured in but I expect that they didn't have a whole lot to drink either.

Yes, I believe there are very good studies on this. Reduction in meat, dairy and alcohol and increases in walking improved health dramatically over during the war. During this time Brits also reduced domestic consumption of gasoline by over 90%!

So in this case a drastic reduction in energy (and specifically in petrol use) corresponded with a dramatic _increase_ in health.

The US uses about 40% of the worlds gasoline, yet it has the poorest health of any industrialized nation, by many measures, and does worse than many 'developing' nation in particular areas (infant mortality...).

Keith,

you should really read Gary Taubes' 'Good Calories, Bad Calories.' In fact anyone who is seriously interested in nutrition should read this. I think it is a brilliantly put together piece of work and quite comprehensive in its review of nutritional research. The biggest problem, as Taubes points out, is the lack of good research that controls for the various dietary components. Most research purporting to demonstrate the harmfulness of a high fat/protein diet does not control adequately, if at all, for refined carbs and sugars.

I have become quite convinced of the health benefits of a high protein diet and have resumed eating more meat, both red meat as well as fish and fowl, and am more strict in limiting sugars and refined carbs. Since I changed my diet back from semi-vegetarian, my blood components have all shown a marked improvement from what was a worrisome trend.

I agree that issues haven't been resolved. What I think has been resolved is that we, in the US at least, have been held in thrall to a grossly faulty dietary paradigm for the past 50 years. This clearly needs to change.

Humans do not gain any benefits, health or otherwise, from eating beef or pork that cannot be gained from chicken and fish. If you are concerned about muscle building aspects, realize that the strongest men on the planet gorge on fish and/or chicken (along with roids and groho).

No thank you, I won't be reading Gary Taubes' book "Good Calories, Bad Calories." While having some additional ammunition and credibility to shoot down this pro-Atkins writer on TOD discussion boards wouldn't hurt, wading through this book is still almost certainly a waste of time.

Gary Taubes is the the author of the infamous article "What if it's all been just a big fat lie?" in the New York Times magazine, which attempted to prop up the Atkins diet with pseudo-scientific documentation. This viewpoint is completely without support within the scientific community and is just another example of the distortion of science for private profit.

Before his article could be debunked, there had been unashamed "followup" stories on NBC, ABC, and CBS, and the Atkins book had gone to #1 on the New York Times bestseller list. Often Taubes misquoted experts who disagreed with him and twisted their words to make it sound like they in fact supported his ideas. Then he got a $700,000 advance to write another book, probably "Good Calories, Bad Calories."

Scientists are outraged that their position has been deliberately and as far as I can tell, mendaciously distorted by Mr. Taubes. Bonnie Liebman at the Center for Science in the Public Interest has a point-by-point refutation of the article's claims.

http://www.atkinsexposed.org/atkins/105/Center_for_Science_in_the_Public...

And in "Big Fat Fake" Michael Fumento has this elaboration:

http://www.atkinsexposed.org/atkins/62/Hopeless_Fad:_br_Sorry,_the_Atkin...

Best wishes for healthful eating and intelligent analysis,

Keith

I read the rebuttal you posted and found that it indulges in exactly the same faults it accuses Taubes of; cherry picking and arm waving and it lacks specific references to specific research on the subjects at hand.

Really, I suppose there is no reconciling our viewpoints. I find Taubes' work well researched. In his book he hardly mentions Atkins at all and concentrates on what the research shows, which is what I consider to be intelligent analysis with an open mind.

My basic concern with Taubes' book is not that he indulges in "cherry picking" and "arm waving" -- it's about Taubes' intellectual dishonesty. I wouldn't mind reading a book that I disagreed with if at least I could assume that the quotations reflected the source material. Given the evidence here, I'd have to check every single last footnote Taubes has, in order to establish what the source material actually said. And given the overwhelming scientific consensus against not just Atkins or Taubes but against the high-protein diet they advocate, this is just not worth it.

Keith

What is your evidence for such a consensus?

PubMed has a range of articles comparing low-carb and traditional high-carb diets:

Those are the first three papers I found on a PubMed search for high-protein/low-carb diets, and all three support that diet as viable or superior to the standard high-carb diet. This would strongly suggest that there does not exist an "overwhelming scientific consensus" against such diets, and it is misguided and misleading to continually insist otherwise.

The lesson I have learned from this interchange is "think twice about pointing out the obvious." Here's a list of institutions condemning the Atkins diet: The National Academy of Sciences, the American Medical Association, the American Dietetic Association, the American Cancer Society, The Cleveland Clinic, The American Kidney Fund, The American College of Sports Medicine, and the National Institutes of Health. [See AtkinsExposed.org for citations and further rather damning evidence.]

Keith

The bottom line is, what does the research support? My own reading indicates support for the high protein/low carb diet.

You can go online and find any number of blogs with the raging debate, rebuttals, rebuttals of rebuttals, etc. etc.

Go to the original research. Good Calories, Bad Calories has an extensive bibliography.

Last week, the Energy and Environmental Study Institute held a briefing on the "Hidden Health Costs of Transportation Policy."

Presentations with references and other useful links can be found here:

http://www.eesi.org/120308_health_transporation

Everything you need to know about "active transportation!"

The crux of the question is whether or not medical care as we know it impacts "health status" and at what cost. I submit that it does not do so significantly, based on a quote from the Surgeon General (this is an old quote, I used to include in my public health papers in the 1990's) to the effect that medical care accounts for 10% of the impact on health status.

What we will have is increased suffering, from unavailability of pain meds for advanced cancer, and surgery for limited conditions such as appendicitis. Therefore we would do well to look at the list developed by Oregon in the 1990's prioritizing medical interventions for their cost-benefit ratios. This is difficult to do, and imprecise, and may not include my relative's needed procedure, but I think we should dust it off in case we need it soon.

And we should publicize loud and clear the findings that link income inequality to mortality rates, unemployment to alcoholism and domestic violence, preterm birth to substance use by mothers (and the underlying determinants of such substance use (hint: not a question of "moral fiber") and television use to attention deficit disorder and obesity. So far we are relatively quiet on these because they step on the toes of powerful lobbying groups.

How I (would like to) see medical care in an energy-constrained future: much more self-knowledge, more responses at the local level, and universal health insurance with explicit rationing (which, by the way, is more egalitarian than rationing by ability to pay).

The biggest bang is not in medical care, which is basically illness care and which serves an essential purpose and which will be affected profoundly as a consequence of peak oil. If you want to maintain and promote health, promote education, clean water, good food, and shelter. Much bigger bang for the buck. One of your own recently reported on the benefits of education. Here is the citation, it says it better than I can.:

Woolf et al, Am. J. Pub Health 2007;97:(4) 679-683 "Giving everyone the health of the educated: an examination of whether social change would save more lives than medical advances."

Summary of Results: Medical advances averted a maximum of 178193 deaths during the study period. Correcting disparities in education-associated mortality rates would have saved 1369335 lives during the same period, a ratio of 8:1. Formidable efforts at social change would be necessary to eliminate disparities, but the changes would save more lives than would society's current heavy investment in medical advances. Spending large sums of money on such advances at the expense of social change may be jeopardizing public health.

We cannot ignore health (illness) care, but it is clear that you get more for your money if you work towards reducing inequality in society. Idealistic, calling for 'extreme' measures: yes. But the whole mess we are in is going to call for extreme measures. Fewer guns, more spades to till the ground and more schoolbooks to till the mind.

Don

This gets into the idea of rationing health care services by age. For instance my 86 year old step-father recently had cataract surgery 100% paid for by the taxpayer. Having been a hard working carpenter most of his life he is very good physical condition for the most part. I wonder if that money would have been better used providing good prenatal care (or contraceptives) to uninsured poor women?

The problem is that the health care system is totally unsustainable to begin with; we can't build our way out of the health care hole. If the current US health care system were spread among every US household it would cost $11000 per year per household so we ration healthcare by price and probably at least a third of that in un- or under-insured so complete coverage would be even more expensive under the 'best-healthcare-in-the-World'.

First, any system that doesn't attempt to cover all citizens is basically 'reverse Robin Hood' with tax payers subsidizing rich who can afford high deductibles or the poor/elderly/children get charity under morally questionable 'handouts'.

For any health care system to offer real services to every citizen will force 'rationing' of care. I think around 50% of medical treatment is 'elective' and this is being subsidized by the taxpayers; so we need to drastically reduce or eliminate that.

Prevention and lifestyle changes of course are essential but would require intervention in the freemarket, banning

excessive sugar, trans-fats, stimulants in foods, ban smoking, reckless behavior, etc. Of course, libertarians will be outraged but costs will come down over time.

It's doubtful that the insurance industry will be profitable enough to pay for health care in the future and they should be removed from the equation. The government should allow people to save toward old age medical expenses through tax-free medical savings accounts. The rest of the medical system would be

non-profit charity work.

One way to reduce energy is to decentralize medical care, closing large hospitals and localizing medicine. This would also increase the level of preventative medicine.

Absolutely. Universal health care MUST be fee-less and equal access to avoid this problem. Every discussion needs to start at this point, else it is wrong on the face.

At that point, rationing is the issue. How and why? The best system would apply rationing criteria to the quantity of specific services available, with services designed to aleviate deliberately self-inflicted diseases at the lowest priority, and stong public education on how to avoid.

THE ENERGY SIDE

The united states has been sucking it's oil mostly from OPEC and SA for fifty plus years, and no small daily amount at current levels, these supply output levels are forecast to decline very rapidly as is already true concerning the north sea oil production and Mexico's oil production. What this means is cheap oil is unsustainable.

TIME is what we need as we continue to try and address our energy supply concerns. since the recession is forecast to last some few years if ever to recover, the living standard we now have, has already declined severely for many,

Nuclear is the best answer for affordable electricity but yet not enough people realize what it will be like to live in a world without this critical utility. it really doesn't matter to me any more becouse the """ green lobby""" is set to put many in the dark as they can, by my study at the current rate of supply loss, the grid must fail simply BECOUSE it is losing supply, so I quit. later, freezingtoes.

As a neurosurgeon, I can concur with the thought that our system is completely unsustainable.

My group has five neurologists and four neurosurgeons in it. In October of 2007 I had our office manager calculate what our income would be if we received Medicare rates for all of our patients. Two of the nine would have had viable practices. The rest of us simply would be unable to pay our overhead and malpractice, and stay in business.

Most of the discussion above relates to lifestyle changes that affect the health of the population. A few minor factors that keep me in the emergency room late at night would be easy to alter if the population wanted to. Not driving drunk, wearing a safety belt, wearing a helmet are a few that come to mind. I suspect the population in general will only alter their behavior when healthcare is no longer available.

I seriously doubt that neurosurgery will continue to be practiced in a similar fashion in ten years. My specialty is extremely dependent on high-technology being readily available, such as MRI scanner's, linear accelerator's, microscopes, high-speed drills, and non-reusable sterile equipment. Somewhere along the way, our society will have to figure out that demanding surgery for malignant brain tumors in 85-year-olds does not have sufficient societal benefit, and should not be offered. The mere suggestion to a family at this time, that there loved one has lived a long life, and maybe we should not spend $100,000 to prolong their life another 4 months is usually greeted with a great deal of hostility.

There was a time when it appeared that there might not be sufficient silver to coat all of the xray films needed for modern medical care. Digital photography and radiography largely solved this problem. Now one can wonder if there will be sufficient helium to keep all of the MRI units functioning??

http://www.praxair.com/praxair.nsf/7a1106cc7ce1c54e85256a9c005accd7/9354...

http://www.metrowestdailynews.com/archive/x471274468

Agree completely, pinealone. You'd like the book How We Die by surgeon Sherwin Nuland.

Should surgery be performed on a 97 year old male with an aortic dissection?

http://www.asahq.org/Newsletters/2007/02-07/crowsNest02_07.html

It bought him 2 years....

http://www.cnn.com/2008/HEALTH/07/12/debakey.obit.ap/index.html

But would the resources be best used on a teenager who might have 5 decades left?

Or a 55 year old who is still supporting the teenager?

Tough questions indeed.

The mere suggestion to a family at this time, that there loved one has lived a long life, and maybe we should not spend $100,000 to prolong their life another 4 months is usually greeted with a great deal of hostility.

My wife is in primary care and manages her patients in the hospital too. The stories she relates about fantastical end of life expenses are truly astonishing. I keep telling her to be patient, the future will be more about good old fashioned triage and hospice.

I think the elderly and terminally ill would feel less unease about being triaged out of costly heroic/futile interventions if they could be assured of getting effective pain management (i.e., narcotics). Because of our "war on drugs", our government has forced our health care industry to be far too stingy with the narcotics. I suspect that some health care providers are even reluctant to use what they actually are allowed to, just because they are afraid to risk getting hassled by the DEA goons. Adjusting laws and attitudes with regard to this could be an easy way to reduce those end-of-life medical expenditures.

Actually, equality of wealth is a huge factor in life span and health. Just look at the US, with it's huge discrepancies, and the population getting shorter, fatter, and losing the longevity benefits with the rest of the First World Democracies.

Libertarian, free market skeptics Take a look!

It's all "public health".

cfm in Gray, ME

I am always hopeful when I see the word sustainability, thinking it might mention population growth. But alas, no, some stuff about an aging population but nothing about the fact that we go up by millions each year in population. Perhaps my thinking is wrong and that is sustainable. Or maybe sustainability only covers a finite period like "till my kids die".

As one who has been interested in population and resources since the 50's, was once active in the former ZPG (Zero Population Growth), and has contributed to Planned Parenthood and Republicans for Choice; I consider population problems - including those noted by Garrett Hardin - a given. It would be exceedingly tiresome to insert the word "population" in every post dealing with energy and related matters.

I don't mind referring every problem to population growth PROVIDED global equality is first granted. Bring the entire world to an equal level of wealth and GINI index first, then discuss what measures may be necessary to control population.

GINI?

--- G.R.L. Cowan (How fire can be tamed)

I don't mind referring every problem to population growth PROVIDED global equality is first granted. Bring the entire world to an equal level of wealth and GINI index first, then discuss what measures may be necessary to control population.

Which do you think is a more likely scenario in terms of wealth equalization - the whole world lives at China and India's level, or the whole world lives at Western Europe's level?

Would you agree that (at least implicitly) you are saying that the population growth that Canada and the United States experience from immigration makes things worse in those countries, but that you favor it because it makes things better for the immigrants coming from their homelands of China, India, Mexico, etc.

It would be exceedingly tiresome to insert the word "population" in every post dealing with energy and related matters.

I find the excuses that people come up with as to why they don't/can't/won't mention population growth when proposing the same partial-solutions to fossil fuel depletion over and over again, both tiresome and alarming. To paraphrase Tad Patzek - "It's like talking about mopping and drainage techniques while ignoring the leaking pipe." And to imply that it is an unstated part of the majority (I would say all but someone would claim they once saw it mentioned) of partial solutions offered here is either naive or disingenuous.

The Gapminder site is so cool!

I would encourage everyone to meditate on figures 2 and 3 above, particularly noting the difference between Costa Rica and the US in figure 2, and between Cuba and the US in figure 3.

It is clear that countries like Costa Rica and Cuba get far more "bang for the buck" than the US. To put it another way, we in the US are getting a very, very bad deal. It is clearly evident that we COULD do much better - that we could preserve a very high quality of life (wrt to health) with far fewer resources devoted to health care than at present.

One way of looking at our present troubles is that it is releasing vast quantities of resources which are not currently productively employed.

A grossly inefficient health service, which consumes much of the US GNP, but provides low general health levels for the populace, as it is fighting a loosing battle with the health issues arising from gross inequality, is on it's last legs.

Much of the troubles of GM and the car industry can be attributed to their having to stand in stead of the State in the provisions of very expensive health care and pensions.

On the main subject of this site, it is clear that the rule of the private automobile is grossly wasteful, and that other transport arrangements are far more efficient.

In a similar manner, much of the brightest and best in the labour force is fiddling around (literally!)by slicing up and repackaging debt and insurance.

On a resource basis, a fraction of present output could provide rail and energy alternatives, whilst the intelligentsia could actually create some value.

We are in a severe situation - as Chuchill said:

"The time for procrastination and delays and excuses is over, we are into a period of consequences."

At least we are now starting to deal with reality, not fantasy.