The 2008 IEA WEO - Oil Reserves and Resources

Posted by Phil Hart on November 20, 2008 - 11:28am in The Oil Drum: Australia/New Zealand

True to their word, the 2008 World Energy Outlook represents a significant development by the International Energy Agency (IEA) in the philosophy and methodology of their oil supply forecasts. The report attempts a bottom-up model of the world's oil production potential and even revises down estimates previously taken at face value from the United States Geological Survey (USGS). The tone of the report has also changed dramatically, with an urgent call for investment in additional oil projects to avoid production shortfalls by 2015.

Despite those significant changes, the report still relies on inflated estimates of reserves from OPEC countries, overplays the contribution of reserves growth due to technology and predicts the reversal of a decades long trend of declining oil discoveries. These are the real factors that will send oil production into decline, but at least now we have some numbers we can discuss and analyze instead of a decade of blind faith in oil market economics.

This article is part of a series of posts on the IEA 2008 World Energy Outlook, which includes other articles on issues more closely related to production. In this post, I review the IEA figures for conventional oil reserves and future resources, including natural gas liquids (NGLs). The chart above shows that the IEA's estimate for these resources amounts to 3,577 billion barrels, or approximately 3.6 trillion barrels. I will show that a better estimate is 2.5 trillion barrels, a reduction of 1.1 trillion barrels.

Resources relate to the total amount of oil and NGLs that can ultimately be produced, rather than the amount of production in any given year. However, even with 3.6 trillion barrels of resources, the IEA just barely manage to show oil production increasing to 2030 at an anemic annual rate of two hundred thousand barrels per day. According to the IEA:

Worldwide production of conventional crude oil alone increases only modestly from 70.2 mb/d to 75.2 mb/d over the period. (Page 250)

With 1.1 trillion barrels less resources, the result is likely to be much lower.

The first item on my initial slide (repeated below) is cumulative production - the amount of oil extracted to date. This is the only figure about which there is little to dispute. In the remainder of this article I will reassess the IEA's other figures for (1) Remaining Reserves, (2) Reserves Growth and (3) Undiscovered Resources.

Remaining Reserves

Companies producing oil make estimates of the amount of their 'proven' reserves remaining. These are generally published in financial statements, and are a matter of public record.

Despite the vagaries of financial reporting standards for oil reserves (which the IEA report comments extensively on), the estimates for reserves in Non-OPEC countries can be taken as a reasonable estimate. OPEC reserves on the other hand are the "toxic low-doc mortgage backed investments" of the oil world. At issue particularly are the large fraction of world reserves reported by National Oil Companies in the Middle East. The reserves of these companies are not audited, which the IEA recognises in the following statement:

Auditing reserves and publishing the results are far from universal practice. Many oil companies, including international oil companies, use external auditors and publish the results, but most National Oil Companies do not. (Page 199)

OPEC Reserves (Paper Barrels)

There are strong reasons to believe that OPEC reserves, particularly for Middle Eastern countries, are considerably overstated.

Stated Oil Reserves in Selected OPEC Countries

Source: OPEC 2006 Annual Report

When Kuwait raised its stated reserves in 1984 from 67 to 92.7 billion barrels, it had the effect of increasing their production quota at a time of low oil prices, thereby increasing their revenue at the expense of other OPEC members. Not surprisingly, the next year Venezuela doubled its reserve estimate. The United Arab Emirates, who previously had 33 billion barrels of oil, must have found an additional 60 billion barrels in a cellar cupboard which they subsequently put on the books in 1986.

Saddam Hussein in Iraq kept things simple with a revision to a clean 100.0 billion barrels in 1987. He then, like many of the others, reported exactly the same figure for a decade. Only by the late 1990's, when that reporting game became patently absurd, did they start reporting minor increases to make the figures look more sensible.

This is nonsense and the IEA even recognises it as such:

According to BP, which compiles published official figures, proven reserves worldwide have almost doubled since 1980 (Figure 9.3). Most of the changes result from increases in official figures from OPEC countries, mainly in the Middle East, as a result of large upward revisions in 1986-1987. They were driven by negotiations at that time over production quotas and have little to do with the discovery of new reserves or physical appraisal works on discovered fields. The official reserves of OPEC countries have hardly changed since then, despite ongoing production. (Page 202)

That is the first and last time the IEA report refers to this fundamental problem with stated OPEC oil reserves.

While $100,000 will buy you access to industry databases with information about oil fields throughout the rest of the world, the information relating to OPEC countries is not much better than guesswork. This year, however, the IEA paid to access such a commercial database from IHS: "a leading global source of critical information and insight, dedicated to providing the most complete and trusted data and expertise".

The IHS data for OECD countries is perhaps the best available, but because accurate reserve estimates for OPEC countries are closely guarded state secrets, their figures relating to OPEC oil fields are less accurate. Why have we become addicted to oil without demanding adequate disclosure from the countries holding the largest share of such an important commodity for the world economy?

While the reported figures are poor, we do have other sources of information about OPEC oil resources. International oil companies, including those based in the United States, operated in the Middle East for several decades before ownership was transferred to state-run National Oil Companies.

International Oil Companies in the Middle East

Oil exploration in the Middle East goes back a century or more and activity accelerated after the Second World War. Western oil companies were heavily involved in oil exploration and production for more than two decades, enough time to build up a considerable knowledge of the giant fields and remaining exploration potential, prior to nationalisation in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Since then, a myth has developed (in their own interest) that if only a western oil company could get back in there and drill more exploration wells then more oil would be found. The reality is that these are mature oil provinces that are quite thoroughly explored. The reason the industry made early discoveries there is because the majority of oil in the Middle East lies at shallow depths in large and easily identified structures. Future discoveries will be limited to smaller structures, or drilling into deeper formations which are more likely to contain gas than oil.

Exploration statistics in Saudi Arabia tell the story another way. 80% of Saudi Arabia's oil resources were discovered by the first 20 new field wildcat exploration wells between 1935 and 1965. The last 20 wildcat exploration wells have only found 1% of the resources (Laherrere, 2006). The reason exploration drilling has reduced is because there is not much more to be found: drilling wells cannot find oil that is not there.

One man who has first hand experience of reserves accounting in the Middle East is Jeremy Gilbert, who provided this quote:

Jeremy Gilbert, former BP Chief Petroleum Engineer

There were people from the International Oil Companies still working with virtually all the OPEC country National Oil Companies in the late 1970s. From talking to a cross-section of them we can be sure that the numbers quoted for OPEC reserves in the early 1980s (before the revisions) were reasonable.

I was more or less responsible for the Iran reserves compilation in 1977 and 1978 and I worked in Abu Dhabi and Kuwait in the early 1970s: I am quite confident that the numbers shown for these countries in the early 1980s are good; they are possibly a little conservative, because there was some reluctance by the western International Oil Companies to make big capital investments in improved secondary/tertiary recovery which might have led to slightly higher numbers, say 5% more at most.

Since we know from service company and other sources that there were no multi-billion barrel discoveries in these countries in the mid 1980s there can be no technical basis on which reserve estimates could have later increased as reported by the individual National Oil Companies.

It is probable that the archives of BP, Shell, ExxonMobil etc., contain reports from the period which would confirm all of this. These companies provided technical-expert teams which regularly reviewed field performance data and reserves estimates with the technical staff of the operating companies during the 1970s.

Jeremy Gilbert's quote indicates that the reserves stated in 1983 were relatively accurate, but that there is little justification for the big increases countries reported in the following years.

The International Oil Companies (such as BP, ExxonMobil, Shell and Total) are running out of good options elsewhere, so it is natural that they now want a piece of the action where most of the remaining resources are. This is the reason for their public agenda pushing for greater access to Middle Eastern resources. The problem is that their argument that the Middle East needs them is wearing thin. The International Oil Companies sold many of their specialist capabilities to oilfield service companies (such as Schlumberger, Halliburton and Transocean) long ago. Those service companies now operate in the Middle East just as they do anywhere else, as subcontractors to the National Oil Companies.

Despite their desperation, the International Oil Companies have very little to offer, and the IEA has accepted as much:

Higher oil prices and a growing conviction among political leaders that national companies serve the nation's interests better than private and foreign oil companies have boosted the confidence and aspirations of national companies, some of them rivaling the international companies in technical capability and efficiency. (Page 333)

National companies are becoming more technically proficient and better able to handle the challenging new developments with the help of the oilfield-service companies. (Page 334)

Saudi Aramco in particular could lay claim to being one of the most capable oil companies, and it is successfully executing some of the largest ever oil field megaprojects. That said, its disclosure standards do leave a lot to be desired.

Kuwait Comes Clean, UAE Downgraded

Kuwait oil reserves only half official estimate

19th January, 2006"Petroleum Intelligence Weekly learns from sources that Kuwait's actual oil reserves, which are officially stated at around 99 billion barrels, or close to 10 percent of the global total, are a good deal lower, according to internal Kuwaiti records," the weekly PIW reported on Friday. It said that according to data circulated in Kuwait Oil Co (KOC), the upstream arm of state Kuwait Petroleum Corp, Kuwait's remaining proven and non-proven oil reserves are about 48 billion barrels.

In a previous IEA report, World Energy Trends 2005 – Middle East and North Africa, the IEA have themselves downgraded reserves estimates for Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates. Kuwait was estimated to have 'proven plus probable' reserves of 54.9 billion barrels (slightly higher but similar to the leaked figure above) while the UAE was estimated to have 55.1 billion barrels.

These two revisions alone represent a reserves downgrade of almost 90 billion barrels. Yet there is no evidence that the IEA has used these lower figures in their 2008 World Energy Outlook. They have instead reverted to their reliance on OPEC and IHS.

Assessment of Saudi Arabia's Giant Oil Fields

While Saudi Aramco and the NOCs of other OPEC countries publish many technical papers, they consistently remove references to particular fields or locations to deter others from drawing conclusions about their overall reserves. However in May 2007, after months of painstaking forensic work piecing together charts and information from dozens of technical papers, Stuart Staniford and Euan Mearns prepared separate assessments of Ghawar, the world's largest oil field in Saudi Arabia.

Subsequently, JoulesBurn used satellite observations of drilling rig locations around Ghawar to provide independent confirmation for the findings and predictions from Stuart and Euan's investigations. (JoulesBurn has also already provided his more detailed critique of the IEA 2008 Saudi Arabia analysis).

Taken together, these two pieces of research above constitute an unprecedented challenge to the integrity of the IHS oil database, the blind acceptance of stated OPEC reserves by the IEA and the idea that the Middle East can easily meet the expanding future oil production needs of the world.

For comparison, the IEA published their estimate of Ghawar's size, based presumably on the IHS database:

All of the 20 largest producing fields are super-giants, of which Ghawar, with 140 billion barrels of initial reserves, is by far the largest. (Page 226)

The conclusion of Stuart Staniford's analysis was that the Ghawar field had initial reserves of 96 billion barrels (+/- 15 billion). In this one giant field alone, we therefore have 40 billion barrels of overstated oil reserves. The IHS data for OPEC fields and the IEA's reliance on it must be called into question.

Counting the Paper Barrels

The "quota wars" in 1984-1988 led to total upward revisions of 284 billion barrels. OPEC oil production since 1985 has been more than 170 billion barrels but this has not been subtracted from reserves estimates either. Adding these two figures gives a total of 454 billion barrels, although some allowance must be made for the real discoveries and field development work that has been made since then.

In a May 2008 article Oil Reserves: Where Ghawar goes, the rest of OPEC follows, I combined Stuart's work on Ghawar, Euan's additional analysis of the Abqaiq field, a 1979 report to a US Senate Subcommittee on "The Future of Saudi Arabian Oil Production" and the IEA revisions for Kuwait and UAE (above) to estimate that OPEC oil reserves in total are overstated by some 340 billion barrels.

With such secrecy around the real figures comes enormous uncertainty. However, a conclusion that OPEC oil reserves are overstated by between 250 and 450 billion barrels is robust.

Reserves Growth

The second figure that needs revision is that for "Reserves Growth", which the IEA sees as playing a very important role:

A growing share of the additions to reserves has been coming from revisions to estimates of the reserves in fields already in production or undergoing appraisal (reserves growth) rather than from new discoveries. (Page 203)

The IEA also discusses the different factors that can lead to reserves growth:

- Geological factors: The delineation of additional reserves through new seismic acquisition, appraisal drilling or the identification (using well-bore measurements), of reservoirs that had been previously bypassed.

- Technological factors: An increase in the share of oil in place that can be recovered through the application of new technologies, such as increased reservoir contact, improved secondary recovery and enhanced oil recovery.

- Definitional factors: Economic, logistical and political/regulatory/fiscal changes in the operating environment. (Page 210)

Geological factors can be summarised as increasing the estimate of the Oil Initially In Place in the reservoir (OIIP) or the recovery factor (ie. how much of the oil in place can be produced). At the time of discovery of a new oil field, there is large uncertainty in these estimates, but this reduces after a field has been producing for several years.

The technologies that most significantly increase recovery of oil from existing fields, particular secondary and tertiary recovery, have been standard industry practice for many decades. While there are further developments to be made, the largest and easiest gains have already been achieved. External factors such as high oil prices have not been as constant, but are the least significant of the three. An ageing workforce and other capacity constraints also limit the speed with which other measures can be implemented. The nature of the game is that these gains will be extracted slowly over a long period of time.

Reserves Growth Case Studies

There are a handful of celebrity oil fields that show a remarkable increase in reserves as a result of additional development work. The World Energy Outlook featured one of these, the Weyburn field in Canada:

But cherry-picking one example is not very helpful. The chart below shows the reserves estimates for a number of UK North Sea fields, demonstrating just how volatile and uncertain reserves estimates are.

Source: Harper (BP), ASPO Berlin, May 2004

There is a great deal of uncertainty with early estimates of an oil field's reserves but an oil company's best estimate of 'proven plus probable' reserves is just as likely to go down as up. Increases in reserves due to application of new technology or changing economic assumptions are small compared to the total variability.

From the above chart, it would be easy to pick one field with a dramatic story of reserves growth, but the average is one of only slow growth over an extended period of time. So it is inappropriate for the IEA to talk about the returns due to Enhanced Recovery using CO2 in the Weyburn field as though that same experience could be repeated everywhere. Generally such techniques are only economic where standard production practices are not effective due to poor characteristics of the particular oil field.

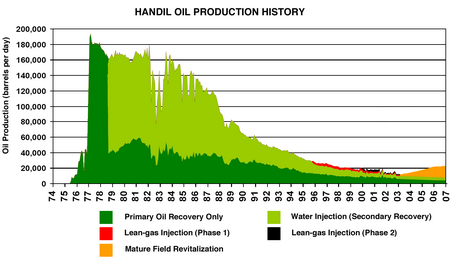

In How Technology Increases Oil Production, I analysed a more representative story about TOTAL's giant Handil field in Indonesia:

Adapted from Journal of Production Technology, January 2008

What is simply described as "Mature Field Revitalization" comprises many years of technically challenging study and modeling followed by intensive application in the field. For the engineers and geologists involved this was no doubt rewarding work.

Yet for a substantial investment of time, money and effort in this giant field, we gain just 10,000 barrels per day of oil production towards the end of its field life. Nevertheless, this was the most significant of several case studies featured in the Society of Petroleum Engineers' January 2008 Journal of Production Technology. While there will be isolated fields that perform better, there will be many more where such activity is economically marginal at best.

Why then, has the 'reserves growth' argument become so prominent?

A Happy Marriage: USGS and IHS

In their 2000 study, the United States Geological Survey estimated 730 billion barrels of reserve growth over the thirty year period from 1995-2025. This describes an annual reserves increase of 2.5% which is far greater than oil company's observations of their own fields. The primary reason for this is that the USGS looked at conservative 'proven' reserves rather than the best estimate of 'proven plus probable' reserves.

The story, however, seems to get more interesting. Since 1995, IHS has been revising up their field estimates, especially for giant fields in the Middle East. Former TOTAL petroleum engineer Jean Laherrere has roundly criticised this as "political pollution of technical databases". It has been suggested that these revisions help bring the IHS into favour with the OPEC National Oil Companies, perhaps earning them important new clients.

Curiously, since these type of revisions have been applied over the last decade to the giant OPEC fields (which contain a large fraction of total world oil reserves), it also means that when the USGS go back and look at the IHS data almost a decade after their original study, they find evidence that reserves are growing in line with their predictions - but the data that they are using to reach this conclusion may be almost completely arbitrary!

Taking just one example of these revisions, the recovery factor for Ghawar in 2001 in the IHS database was a reasonable 47%. By 2004 the recovery factor was increased to 60% and in 2006 increased again to an incredible 70% (Laherrere, Groningen, 2006). This compares to a recovery factor of around 55% determined by Stuart and Euan in their forensic study of Ghawar. A 70% recovery factor is unlikely even in the high quality northern sections of this field, but is wildly implausible across the field as a whole.

Re-assessing Reserves Growth

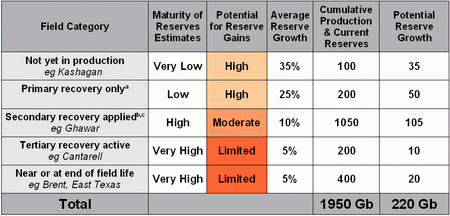

In Shedding Light on the Question of Reserves Growth, I suggested an alternative model for estimating the potential for reserves growth. A summary was also published in the June 2007 Journal of Petroluem Technology in response to an earlier opinion piece from CERA's Peter Jackson.

This model recognises that as fields get older the maturity of their reserves estimate improves and the scope for future reserves growth reduces. This reflects, amongst other factors, the field progressing through different development stages (see the original article for more detail).

The figures in this table are rough estimates at best, but they correctly describe the scale of what reserves growth could achieve. Since 90% of production now comes from fields more than 20 years old, our resource base is very mature. While oil field reserves may have 'grown' 10-20 per cent since the 1980s, we should not expect the next 20 years to deliver the same gain. Discovery of new fields has tapered off to low levels and the easy pickings for increased recovery have already been had.

Reserves Growth - Double Trouble

There is also a compound failure in the IEA approach to reserves growth. They are taking an optimistic assessment of how much reserves grow over time, and multiplying it by a clearly inflated figure for OPEC reserves. A moderate reduction in the assessment of reserves growth, multiplied by a figure corrected for OPEC overstatements yields a significantly lower total estimate for reserves growth.

The IEA are to be congratulated for a lower assessment of reserves growth this year (402 billion barrels total) than previous estimates from the USGS (730 billion barrels over 30 years). However, their arguments and the trends in IHS data are misleading and a figure that is lower still, around 200-250 billion barrels, is far more likely.

Undiscovered Resources

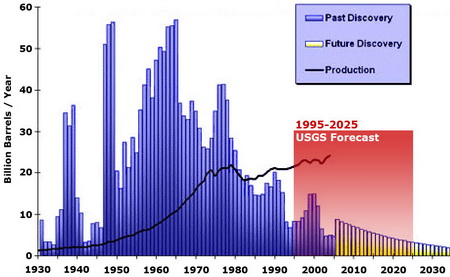

The third and final figure that needs revision is 'Undiscovered Resources'. The World Energy Outlook provides this graphical summary illustrating that oil discoveries have been declining since the 1960s and that production has exceeded discoveries since the 1980s:

The volume discovered has fallen well below the volume produced in the last two decades, though the volume of oil found on average since 2000 has exceeded the rate in the 1990's thanks to increased exploration activity (with higher oil prices) and improvements in technology. (Page 197)

The following chart tells a similar story but on an annual basis and over a longer time scale.

(Discovery Source Data: Longwell (ExxonMobil), World Energy, Vol 5 No3 2002)

The yellow bars are an extrapolation of the oil discovery trend, which sum to an estimate of around 200 billion barrels remaining to be discovered. In contrast, the red box shows the average amount estimated to be discovered by the USGS each year between 1995 and 2025 (totaling 939 billion barrels). More than ten years into their forecast period it is clearly implausible that their forecast could be met (as Rembrandt has also discussed). The IEA take a figure of 805 billion barrels as the ultimate resource yet-to-be-discovered. That still implies a radical departure from the discovery trend and appears hopelessly optimistic.

It could be argued that exploration in Iraq, extreme Arctic areas and possibly even deepwater offshore Brazil have been constrained by external factors and that discoveries in those regions could therefore represent a break from the prior discovery trend. There is only a limited basis for this claim though.

While the Arctic has some petroleum potential, the alternating presence of ice caps over geological timescales causes fractures in the underlying layers, making it unlikely that large petroleum accumulations have survived intact. Additionally, the Arctic is more likely to be gas rather than oil-prone. Recent Brazilian finds provide extreme technical challenges and it is not yet clear how much will ever be economic to recover. Discovery potential in Iraq is also highly speculative, although no doubt significant compared to limited potential elsewhere. In short, these provinces could increase future discovery above 200 billion barrels, but more than 300 billion barrels is highly unlikely.

World Oil Resources

Having reassessed the three categories of resources, it is now possible to present a more robust picture of the resources underpinning future production:

Rather than having produced 32% of a 3,577 billion barrel resource, we have more likely consumed 45% of a 2,500 billion barrel resource. The estimate is only slightly higher than recent publications by Laherrere & Wingert and Campbell, who estimate global ultimately recoverable conventional oil resources at 2,250 and 2,270 billion barrels respectively. Note that of the remaining 1,370 billion barrels in the Table above, some 200 billion barrels are Natural Gas Liquids which have only two-thirds the energy content of crude oil and cannot be used by much of the existing transport fleet and infrastructure.

In total, our remaining conventional oil and NGL resources are more likely only 55% of what the IEA concludes in its 2008 outlook. Conventional oil and NGL production in 2030 is therefore likely to be 50-60 million barrels per day, compared to the current level of just over 80 md/d. Even optimistic assessments of the potential for unconventional oil cannot close that gap. Oil production will therefore not be greater than 100 mb/d in 2030 as forecast by the IEA, even though that is a reduction of 10 mb/d from their last World Energy Outlook.

Summary

Previously the IEA has openly assumed that the growing gap between future demand and their forecast for non-OPEC production would be met by OPEC, with no quantification of whether OPEC resources were available to match that ambitious assumption. That the IEA has now attempted a resource based estimate for both non-OPEC and OPEC regions is a vital albeit obvious and overdue step forward. In another positive move, the IEA has also seen fit to independently revise down the USGS estimates for reserves growth and undiscovered resources.

The most obvious and fundamental flaw in the IEA report is that OPEC reserves have again been taken at face value. The laws of physics do not stop at the Middle East borders and there is not some mythical abundance of oil in OPEC countries. They do have the largest share of remaining resources but they cannot meet our expanding desire for oil forever.

Despite recognising the OPEC reserves issue, the IEA has avoided confronting it. The poor quality of data for these countries has consequential impacts on the assessment of reserves growth and real discovery trends. We cannot have a robust official forecast of future oil supply until we get transparent and audited information concerning oil reserves in OPEC countries.

The IEA has warned that massive levels of investment are required to bring oil resources to market in a timely manner, but the reality is that oil resources are insufficient to meet these forecasts regardless of investment. Oil production will be heading down hill well before 2030, constrained by a fundamental lack of oil resources and not simply a lack of investment.

You can Contact Phil or try these tags for other stories on similar topics:

iea, oil reserves, opec reserves, reserves growth, undiscovered resources, weo 2008, technology, oil discoveries

You know - with oil at $50 - I'm begining to think that old Daniel Yergin was right after all

you can't fight city hall

after all, he is the worlds leading authority

This $50 oil crock will guarantee a massive spike in the near future. We can have a surge of consumption even if the world is in a recession, if oil is cheap enough. The worries about demand in the market are insane, there will never be a shortage of demand but there will be a shortage of oil.

The Youtube video at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T7vGDwGLU7s gives a very excellent, visual explanation for what is happening to the oil prices now. Many have predicted it, and we are seeing it play out. Oil prices spike, causing a recession, which kills demand, lowering oil prices enough for a recovery, which causes demand to rise again and spike prices back up again.

Of course, there is more to this recession than oil (unsustainable amounts of debt), but I think the oil price spike caused this recession to start a few years earlier than it otherwise would have. Right now the primary blowback is the unsustainable credit bubble collapsing, amplifying the effect that high oil prices otherwise would have had. The above video is still instructive.

This is also the "ratcheting down" effect James Kunstler described in his book, "the Long Emergency." Good book.

Phil, your post is excellent and this data really allows us all to develop some insight into "what happens next".

I wonder how much of the oil price decline since the IEA released their report (Nov 12) is due to their own (unrealistic) optimism about future supplies and their (wishful) opinions about the dire impact of the global recession on oil demand?

Right about what exactly? Why is everyone surprised at $50 oil? Do you really think that Americans and Japanese could keep on paying for oil indefinitely with money they didn't have? Everything about our current financial situation points to the system correcting itself, sorting out all the financial imbalances of 2003 - 2008, that resulted from the price of oil going through the roof.

The sad part is nobody will learn anything. Eventually a semblance of normalcy will return. Everything will pick up again, growth will return, oil consumption will increase again, and in 5-10 years time it will hit a limit around maybe 80 mil. barrels per day this time (I'm making this figure up of course, but something slightly less than the current 86 mil. barrels per day peak). The oil price will go through the roof again. Economists will lament the underinvestment in oil fields that was a result of the last recession. "If only we had devoted more resources to develop and renew the infrastructure," they'll say. Another recession will follow. Reload and repeat ad nauseam with a lower oil output peak each time.

Hopefully the physicists will figure out how to harness controlled fusion, but speaking as one of them, don't count on anybody figuring out how to control a chaotic system in the near future.

I think there are a couple of different issues involved. One is that with our current high level of depletion, we may very well be at a point where there is rapid fluctuation in prices, up and down. Readers may have seen the example of whale oil becoming scarce, in the late 1800s. This is a version of the price chart for whale oil. The lines for averages have been added by Oil Drum reader "graywolffe" found here.

So part of our problem may be volatility in a constrained supply situation. This is not a very complete explanation, though, since it does not show a big drop in price.

I think the more basic issue that peak oil causes is ultimately causing the strange price situation we are seeing today. I have been saying that one of the big effects of peak oil would be to "crash" the financial system, so that we would need to start over again with a different financial system, one which is debt plays only a minor role. I have been writing about this since I started writing about peak oil. (See for example this and this).

From my perspective, the economic problems were are seeing today is exactly what I expected peak oil to look like, because once resources (such as oil production) stopped growing, people could not pay back their debt. There would be massive defaults on all types of debt, and the system would crash. (Also see my forecast for 2008.) We have started the financial crash now, and it is now happening in slow motion around us. This is scary to me, but people who only see the $1.80 gasoline don't see a problem.

After the crash, it is not clear exactly what will happen, but I expect oil consumption, and consumption of a lot of other goods, will be a lot lower. Thus, instead of having a nice smooth up and down pattern like US oil production, we will have much more of a drop off. It doesn't match what many people were looking for, but it is likely not far away. Exactly how this crash plays out is not clear--it is unlike anything any of us have experienced before. Low prices don't mean something good. They mean serious disruption of our economic system surrounds us.

That graph is instructive Gail - thanks.

I see it somewhat differently, though I agree with you that peak oil, especially peak in 'net energy' produced from oil (barring being replaced with similar scale energy gain, which it has not) means the end of growth. But that is not what has caused this meltdown in the credit markets, unless indirectly through lack of energy gain attempted to be replicated with increases in virtual wealth and easy money, easier regulations to maintain growth in weaker areas of society (Glass-Steagal).

The overextension of credit with no underlying fundamental backing and the proliferation of human agents trying to swing for fences in the arena where social power is most concentrated currently (paper and digital assets) overwhelmed any energy constraints-whether they were caused by them or not will never be known. Since I started writing here I have pointed out that small amounts of financial (abstract) capital could overwhelm the total size of real capital (partially represented by commodity markets, including but not limited to oil and gas). I don't have time to get the stats right now but if you aggregate the notional leverage allowed to investment banks and hedge funds at the peak this summer (which coincided with the oil peak and peaks in most other commodities and currencies), this aggregate dollar amount would have an order of magnitude greater than the sum total of real commodities consumed. This is THE classic example of Soros' reflexivity concept, as ironically the people who understand the energy future the best, are going broke the fastest (McClendon, Pickens, etc.) The deleveraging would have eventually happened irrespective of the energy situation, though high prices might have kicked it off.

The main difference between what we believe and what the public believes (and here is where my view converges with yours) is that once/if the economy rights itself with some new currency/SDR/Bretton woods arrangement, we will immediately be faced with energy limitations, both price and availability. Oil and other commodity prices give VERY correct signals about current supply demand imbalances but are awful long term predictors of scarcity. At least for things that have no ready substitutes. That is why your whale oil graph is instructive - price signals have ceased to be valid information for policymakers years ago!!!!

Irrespective of all that, whatever the reasons for arriving at our current long-term dire energy straits, the importance of explaining all this and spending so much time on this blog is so that we don't spend our few remaining bullets on wasteful choices that put out immediate fires at greater risk to future. And regarding debt financing, there is a HUGE difference between not being able to repay loans and the publics perception of not being able to repay loans - I suspect the former will happen a good many years before the latter. That's where we are at right now. Hard choices to make. Biophysical and biological constraints (and opportunities).

I'm impressed by your reasoning, but I wonder if "we will immediately be faced with energy limitations, both price and availability " is necessarily true. Now, the general decline in economic activity has brought down the demand for oil to the point that world producers are having no problem keeping up with demand. If the world financial system reconstruction can be accomplished while still keeping world population reasonably fed, we can expect at least a short period of operation under the new financial system before growth again brings oil demand up to available oil supply. There will be, I hope, a short window of opportunity to address energy supply towards the end of the financial turmoil.

Of course, if the financial collapse leads to a failure to plant sufficient crops, then there will be serious loss of life before we climb out of this mess. Such loss of life will decrease the demand for oil, IMHO, and keep oil prices at depressed levels. Maybe, serious loss of life will extend the period of depressed oil demand to the point that your predicted energy shortfall never happen. (Not a preferred scenario, just a different scenario.)

Your talking about this 2.3% decline ? Or about 500kbd ?

From Gail:

You know, understanding the problem has hardly helped me envision a "new system". Could anyone out there present us a system where money supply is not based on dept like ours is? One, where money is not "created" by a central bank writing a note of dept to the government? One that is also flexible, unlike one based on Gold, for instance?

How about basing it on a unit of energy - the Watt, for instance (as in Watt? Money? :-)

Nate, you know a lot about how "it works", do you have a proposal about how it *could* work? I've been waiting for this financial crisis aout four years now (debating with John Denver back then) but I've never come up with a serious proposal on how to change "the system" based on geometric interest-based growth..

Cheers, Dom

It's very complex. And the further we go down this path the less politically viable it will be, but there is a long history of an energy theory of value starting with the Technocrats in the 1930s (King Hubbert one of their founders). We would base our currency system not on trust, not on gold, but on energy stocks and flows. Countries without much indigenous energy would have to trade for it (labor, and other resources). Our annual spending budget would have to come down dramatically which would be the problem, and would be linked to some combination of extractable fossil fuels and renewable systems - over time the objective would be to have currency based entirely upon the renewable flow rates of 'sustainable' infrastructure.

The problem with such a forward looking, radical system is in the end it wouldnt be radical enough. Because once we aligned to our energy use, there would then pop up other limiting variables like water and soil...i.e. even if we were 'energy rich' in the future just as we are 'currency rich' right now, we might be decoupled from the reality of all the water used in energy production.

A multicriteria model of natural resources and ecosystem services would be the ultimate way to base a currency. But that is 5 steps beyond what current policymakers are thinking. By discussing these things in a forum like TOD, one hopes that such an idea or a related one becomes only 4 steps ahead. The rest is a leap of human faith.

It's always worth remembering that gold and silver represent energy indirectly. They embody the huge amounts of energy necessary to mine them. As oil becomes scarcer, the embodied energy value of these metals will only increase.

O.k., let's all go join the Technocrats (after reseaching Wikipedia:-). But Nate's right, it's all very one-sided. At first, when I came into the circles of thought where "everything" is based on energy, I immediately thought of the physiocrats of the 18th century:

I realize the role of (commercial!) energy at the present, and that understanding it might help us construct a new monetary system. But Nate's right, we still need something neutral to "price" all of the above.

Cheers, Dom

I really like the concept. It's very logical really. Almost everyone would agree that a currency could be based on gold, provided everyone on earth did the same, because it has been done in the past. All you're really suggesting, Nate, is that we should expand the list of resources used to back currency from just gold, to every sustainable resource used in society. Conceptually its not that large a leap. However, I haven't taken the time to think through the reality of it yet, suspect the devil may be in there somewhere.

Also that added criterion "sustainable" on resources could be a kicker at the outset. Would that mean that eg. remaining oil resources become worthless? Obviously not ideal in a transition period.

Very complex in detail.

With a gold-backed currency, the promise is that any note can be exchanged for equivalent gold at the local bank, on demand. No overhead compensation to the bank for providing the service.

With an "all-resources" backed currency, would the promise be that any note can be exchanged for equivalent resources of your choice at the local trading market, on demand? No overhead compensation to the market for providing the service?

Interesting effect is that it provides a viable way to establish how much currency any country may have in circulation at any time. No country may establish more currency than the total of their "sustainable resources" .... It at least intercepts this inflation scam we've been caught in. Becomes an issue when jurisdictions try to share a currency, eg. EU. Is a one-time audit of world "sustainable resources" taken, and tha becomes the world limit of ow much currency is allowed to exist?

One big advantage is it provides very solid and slow-to-change exchange rates among currencies, eliminating speculators.

gold, while more of a store of value than a fiat currency, has no real use in a future world where basic necessities are food, water, heat, shelter, etc. Historical civilizations had all of these things so gold became a concentrated store of value. But if I were hungry or cold, I would gladly give up a Krugerand for a multi-pack of heirloom seeds and some gardening tools, etc. I know there is a faction that thinks we should go back to gold standard, which effectively would send gold over $5,000 per ounce. For one thing, those folks are mostly talking their position (i.e. they are long gold, not long societies best interests) and second, backing currencies by gold and we quickly are right back where we started, as gold is not fundamental building block for any economy(other than being needed at the margin in catalytic converters, etc.)

I'm not advocating a gold-backed currency, but an "all-resources" backed currency.

There are some useful ideas out there about backing your currency with a basket of commodities. For example, the ancient Egyptians had farmers bring grain to stores and they'd get a receipt. That receipt could be turned in at any time to get the grain back, so it acted as a store of value and a medium of exchange - a currency.

With the Egyptians, they had the receipt drop in value to reflect losses due to rot and rats. If you brought in 100lbs of grain in March and then came back with your receipt in April, you'd get (say) 90lbs back. So it was a depreciating currency, which encouraged people to spend it quickly rather than hoard it. A classic Keynesian pump-priming, four thousand years before he thought of it.

By adjusting the rate of depreciation, the people controlling the store can have a tax on it, and get revenue for public works. For example, if the grain actually rots at the rate of (say) 2% a month, then you have the currency depreciate at 5%, and use the 3% difference to issue your own currency in payment for labourers building roads or whatever.

Nowadays we'd want to base it on a variety of stuff, grain and cheese and meat and cloth and iron and so on. You'd probably want quotas on some goods, since your purchase of them encourages their production - you don't really want everyone to only grow flax for linen, and have no food. But the basic principle is sound.

There are lots of other possible systems, more when you decide that the two functions of currency - as medium of exchange and as a store of value - are things which can be split from each-other, or one tinkered with a bit.

Now, such a system is never going to be put in place by a central government. Past experiments with currency by the people have been squashed if they threatened the central money supply. Success brings a crackdown, since central governments cannot exist for long if the money they offer isn't wanted.

But if we face a Depression or a stronger civilisation-shaking crisis then it's something which might come up locally. If the central governments are wiped out or simply not around - some years-long version of post-Katrina in the US - then such systems could be very successful. If you're a doomer then you should be investing in a printing press and warehouse rather than buying up gold.

I'm also concerned about how items like "intellectual capital" and "human labour potential" get valued. They should probably be part of the "sustainable resources" setting the currency cap allowed. But if the system of counting those two is at all affordable, the shortcuts required are very liable to give governments a large incentive to encourage population growth among their people, a bad idea.

Conversely, it gives countries a large incentive to increase the levels of skill and education among their populations, a good incentive.

Hello Lengould,

Your Quote:"I'm also concerned about how items like "intellectual capital" and "human labour potential" get valued."

Consider my earlier postings on I-NPK as currency and stored in my speculative 'Federal Reserve Banks of I-NPK':

1. Consider how much "intellectual capital" and "human labour potential" are embedded in the creation and subsequent utilization of I-NPK.

2. From prior posted weblinks: A high-potency I-NPK ratio fertilizer such as DAP might have energy-embedded 5 gallons of gasoline energy equivalent in the 'transformity & distributive' process.

3. A 100 lb sack of I-NPK is damn hard to easily steal [especially if you don't have a wheelbarrow], conceal, or hide. Compare to an equivalent $$$value of fiat cash or precious metal. A thief would rather steal food first.

4. If I-NPK sample testing & certification can be assured--impossible to counterfeit--> the Elements by chemistry & physics don't ever lie.

5. Recall my Ft. Knox posting series: gold bullion stacked outside in machine-gun bunker formation to protect the seeds & I-NPK safely stored inside the vaults.

6. Using RFID tech: each bag could be identified, serialized, inventoried easily, and tracked.

7. At an idealized Liebscher's Law of the Optimum: I/O-NPK combo results in an agro-ERoEI of 20:1. Gresham's Law doesn't apply because O-NPK as a 'substitute' for I-NPK has a high intrinsic value to improve topsoil mulchiness, water-rention for drought, and micro-organism growth. Liebig's Minimum assures a bottom pricing floor for NPK, same as a bag of junk silver coins has a legal tender value of the face value of the coin.

My feeble two cents: have you hugged your bag of NPK today?

Bob Shaw in Phx,Az Are Humans Smarter than Yeast?

Another issue to sort. How does the "sustainable resource" of a country like Iceland get established? A large proportion of their economy is based on harvesting of sea creatures in international waters. It seems unlikely that they would be assigned a "right to create currency" based on their ownership of fish off the continental shelf of the USA or Norway etc. It would need to come down to an evaluation of their population's ability and willingness to do the harvesting combined with regular evaluations of the sustainablity of the proposed rate of harvest, a very difficult item to count. Also gives them an incentive to try to falsly increase the "sustainable harvest rate", which is not a good incentive vector.

Needs a solution.

“How about basing it on a unit of energy - the Watt, for instance (as in Watt? Money? :-)”

I think you are absolutely right, there is nothing funny, or wrong or nonsensical in your suggestion.

It is a very sensible and viable thing to have money based on energy units, that’s what the “New Bretton Woods” should have: "Credits" backed by Energy Drawing Rights or whatever you call it, making, for example, 1 Credit= 1 BOE = 1680 kwh

Let's not forget that whale oil had ready replacements (e.g. kerosene). We are not in the same situation today with oil so the price transition will not be as mild as in the graph.

And in particular, if low oil prices continue because weak or recessionary economies can't afford a higher oil price, our oil reserves have suddenly shrunken because a lot of the incremental barrels may be more expensive than what the purchasing power of consumers can support.

It is now very important and urgent to establish what the production costs will be of the remaining reserve categories otherwise we have a lot of oil in the books but not enough money to get at it, on an annual basis.

See also my comment here:

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/4770/436088

The Graph: Large spike just after peak (23 units), back down to 15 units very soon after, then back up to 23 units, noticeible increase in volatility after "step"/peak. Looks pretty much the same as today except there is a lot more "leverage" with today/petroleum/population hence greater variance.

Is there any parallel with whale oils extreme production quantity volatility at peak to todays situation.

80 mb/d in 5-10 years? Is that because you expect supply to be 80 mb/d in 5-10 years? Because oil consumption today would be well above 90, probably closer to 95 mb/d today if prices had stayed at the level of a few years ago. In 5-10 years, the Chinese economy will be almost twice the size it is today with 8-9% growth (down from 11-12% in the last few years). There is no way that demand will fall in economies growing at the rate we see in Asia. The demand pressures coming from 3 billion Asians in the coming years will put incredible pressure on demand. And OPEC won't cut in their subsidies, it's about stability for them, so expect strong growth in consumption there too, especially on a per capita basis. There's way too much focus on the US and Japan. All the efficiency in the world can't make up for tens of millions of people moving to the cities each year in asia and taking part in the urbanized, industrialized way of living.

Uh...sorry for the ambiguity. I meant oil production, not consumption. BTW, I'm sucking that figure out of my thumb. But my point is that I would not be surprised if we see a sudden drop in production of oil over the next five years as the recession bites. Oil prices will not go up much if at all because oil consumption will be dropping as well. Remember, the Chinese economy is/was only growing because there are/were people with enough (fake) money to buy their goods. If the rich countries don't have any money (or credit lines) to buy Chinese widgets anymore, I don't see how China is going to keep growing. Anyway, as I was saying, oil production may sag in the next five years, not because of geological factors, but simply because of the sagging economic activity. Then it may pick up again as the economy recovers, but, as I originally said, the production of oil won't quite be able to match our current peak (this time, because of the obvious geological limits) which will result in another recession and so on and so forth. Of course this is all just crazy speculation.

It is not clear that the global oil consumption will drop enough to create a glut of supply. This is especially true given the underlying decline in production regardless of the nonsense predictions of enhanced recovery and magic discoveries from the IEA. In the last three years there has been a lot of demand destruction in the third world since they could not afford the price. Now we will have this demand returning even if the developed world is in recession. This needs to quantified but it seems to me that the consumption demand drops in the first world may be offset by price-driven demand increases in the rest of the world. There is just not that much slack in the first world demand. Does anyone expect the US to transition to using half of what it does today?

20% of shipyards in China are shut down. (source Tidewater conf call)

Also - the lower oil goes and the longer it stays the closer observed decline is going to be to natural decline. We (or someone) needs to do an analysis of what happens to oil production at different tranches of IEAs called for $26 trillion in needed energy investment. What happens if there is zero investment. We need to at least know worst case (well, WORST case would be a war, or something we cannot imagine), but worst case while current system functions. If there is zero investment, how soon before supply drop overtakes demand drop? I had originally thought we might have 2 or 3 of these cycles but now I think there will just be one, though it might take 2-3 years. Too many variables to predict with certainty.

Funny, I was thinking the same thing earlier. Seems like a perfect application of the old quip that "even a broken clock is correct twice a day".

Imagine a combined depression and post-peak scenario where demand is going down at the same rate as post-peak supply, the oil price signal will be useless in understanding that we have just past the peak.

I think we're in that scenario right now--except that the demand curve for oil is shifting downward and to the left faster than the supply curve is moving leftward and upward, hence the falling price of oil. In the short run, fluctuations (and especially expected fluctuations) in demand dominate long-run supply factors.

Eventually, of course, the rising cost of a marginal barrel of oil will be reflected in a higher price, but "eventually" could turn out to be a couple of years if the downturn in global GDP is long and severe.

The one thing about oil prices we can be sure of is increased volatility; we've already seen a lot of that, and we're going to see more.

Will there be a 1 Yergin party at 38$?

Just like the one when oil was $11 and forecasted to go to $5? Let me know if anyone shows up...

I really don't understand you. Yet another who thinks the melt down of the world's financial systems with all the horror and misery that entails, is a cause for gloating.

The price of oil has crashed because demand has crashed because people's homes, jobs, investment, future financial security and therefore purchasing power is being destroyed. I find it strange that the world teetering on the edge of a second great depression, a few years earlier than even most doomers predicted, makes you happy.

Who's gloating? Just making a point. Plus are you telling me the other side wasn't gloating when oil was heading in the other direction and folks were struggling with high energy cost? give me a break... how many double, triple, and quad yergin parties were there on the way up! C'mon guy!

On the more doomer side of the spectrum the humour, I would say, is "gallows humour". Better that that crying. Perhaps you genuinely don't understand that?

I genuinely hope we can find a way out of this. I just have difficulty seeing us do the right thing. If indeed there is a right thing.

Hypocrites are the first in line to call people hypocritical.

Kudos, Phil, this careful examination of the forces at work in reserve estimation and projection is top-notch TOD material. I've just now bookmarked this article, and it will be the impetus to an email to friends and relatives.

It's an excellent summary of our situation, we should add it to the Peak Oil overview section.

Thanks to all of the other Oil Drum contributors who provided feedback to Phil on this article. Phil was kind enough to put it together several days ahead of time, and let the other Oil Drum staff offer suggestions. This kind of teamwork pays off on an article like this.

Good work Phil Hart.

Should any Aramco people monitor this board, please release a couple of SPE papers preferably on Shedgum and North Uthmaniyah performance.

We will take care of your current price problem from there.

FF

In their own unique way, Saudi Aramco did a remarkable job of maintaining some semblance of control as oil prices went sky high and the world asked where all the oil was.

Logically, cutting production should be easier for a cartel, but perhaps the day of reckoning for OPEC is going to come with crashing oil consumption rather than having to admit they couldn't meet demand on the way up?

I'd love to be a fly on the wall at the next OPEC meeting..

Excellent work, Phil. Very accessible for even non-industry people like myself, but also very convincing. I agree with the downward movement of ME estimates, but am yet uncertain that proper consideration has been given to Canada. This article, from 2002, http://ffden-2.phys.uaf.edu/102spring2002_web_projects/m.sexton/ states

Given the relative ease of access to these resoures, and developing technology such as Toe-To-Heel, Shell's frostwall-electric-heat process, coke gassifier hydrogen generation for upgrading, etc., a 10% to 14% ultimate recovery seems, to me, overly pessimistic.

I also note this statement discussing Venezuela 2003 Bill Kovarik at http://www.runet.edu/~wkovarik/oil/3unconventional.html

Venezuela to the Falklands? three to four trillion barrels x .333 x (Area Venezuela to Falklands / Area Venezuela)

Also oil shale http://fossil.energy.gov/programs/reserves/publications/Pubs-NPR/40010-3...

I know, discussion is not popular, and there are some serious questions regarding economics but ignoring this stuff is no more responsible than OPEC jumping its numbers.

As Gail and I pointed out to some of the folks at the EIA back in April when they were touting how much oil is left to find and recover...if the net production rate is low, then it might as well not exist.

True Len...there are many billions of bbls of "technically recoverable" reserves out there. I know of over half a billion bbls of technically recoverable oil just a few hours from Houston. Unfortunately, it would require a sustained price of probably $200/bbl to do so. And one day that price threshold may be reached. But then in lies the problem: one can not toss out a number for recoverable oil in any play without stipulating a price platform. There are 10's of billions (perhaps even 100's) bbls of oil in the pre-salt play off of Brazil. This is an area I've just begun working. But not one bbl of oil will ever be produced from new wells out that as long as oil stays below $60. At $60/bbl = zero new oil. At $150/bbl = billions of bbls.

Now the Falklands may have trillions of bbls of heavy oil. How much will be recovered at $60? At $150? At $250? As I've said before, offering a figure for recoverable reserves in any play without including a price platform is, at best, meaningless, and at worst deceptive.

Seems fairly definitive to me. My point is, it is also an error to declare "Oil has peaked and the use of oil is ended" without also stateing your assumptions on what the maximum price of oil can be.

On tar/oil sands, Christain Science Monitor 2006 states

http://www.csmonitor.com/2006/0512/p04s01-woam.html

I note that these facilities went into overdrive expansion mode when crude went over $40 to $50 / bbl. Agreed costs went higher with the commodities bubble raising input materials costs, but those and oil prices should go up and down pretty much in step, slightly delayed.

So why is Brazil out drilling 2 km into salt domes under a km of ocean? Good question. Perhaps they'll need to wait until Kuwait's empty.

The report is based on official statistics.

http://business.maktoob.com/NewsDetails-20070423098206-Kuwait_seeks_prob...

I've also seen figures in reliable news media (Bloomburg I think) which placed the costs of each Mideast oil producer's production in a range from $50 to over $100 / bbl. Perhaps they were stating replacement discovery costs.

Very opaque.

Before that happens the economy is dead.

The world has just found by trial and error that high oil prices have led to bank failures, company collapses and all the rest of it.

I think you're optimistic in your hope for disaster.

You got it.

+

With rising prices alternatives (efficiency, renewables...) become more and more competitive.

+

As soon as investors realize all the costs and risks they'll become very vary of investing in this stuff.

=

So maybe the $250 oil will never be make it to the surface.

Hi Lengould,

Oil Shale is not oil, nor is it shale, and the EROEI for oil shale stinks and will always stink, even when oil hits $1,000 per barrel

The World Energy Council makes the following assessment about the potential of oil shale energy:

“If a technology can be developed to economically recover oil from oil shale, the potential is tantalisingly enormous. If the containing organic material could be converted to oil, the quantities would be far beyond all known conventional oil reserves. Oil shale in great quantities exists worldwide: including in Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Estonia, France, Russia, Scotland, South Africa, Spain, Sweden and the USA.

The term ‘oil shale’ is a misnomer. It does not contain oil nor is it commonly shale. The organic material is chiefly kerogen and the "shale" is usually a relatively hard rock, called marl. Properly processed, kerogen can be converted into a substance somewhat similar to petroleum. However, it has not gone through the ‘oil window’ of heat (nature’s way of producing oil) and therefore, to be changed into an oil-like substance, it must be heated to a high temperature. By this process the organic material is converted into a liquid, which must be further processed to produce an oil which is said to be better than the lowest grade of oil produced from conventional oil deposits, but of lower quality than the upper grades of conventional oil.

There are two conventional approaches to oil shale processing. In one, the shale is fractured in-situ and heated to obtain gases and liquids by wells. The second is by mining, transporting, and heating the shale to about 450oC, adding hydrogen to the resulting product, and disposing of and stabilising the waste. Both processes use considerable water. The total energy and water requirements together with environmental and monetary costs (to produce shale oil in significant quantities) have so far made production uneconomic. During and following the oil crisis of the 1970’s, major oil companies, working on some of the richest oil shale deposits in the world in western United States, spent several billion dollars in various unsuccessful attempts to commercially extract shale oil.

Oil shale has been burned directly as a very low grade, high ash-content fuel in a few countries such as Estonia, whose energy economy remains dominated by shale. Minor quantities of oil have been obtained from oil shale in several countries at times over many years.

With increasing numbers of countries experiencing declines in conventional oil production, shale oil production may again be pursued. One project is now being undertaken in north-eastern Australia, but it seems unlikely that shale oil recovery operations can be expanded to the point where they could make a major contribution toward replacing the daily consumption of oil worldwide.

Perhaps oil shale will eventually find a place in the world economy, but the energy demands of blasting, transport, crushing, heating and adding hydrogen, together with the safe disposal of huge quantities of waste material, are large. On a small scale, and with good geological and other favourable conditions, such as water supply, oil shale may make a modest contribution but so far shale oil remains the ‘elusive energy’.”

The 2007 GAO study concluded that, “it is possible that in 10 years from now, the oil shale resource could produce 0.5 million to 1.0 million barrels per day.” But the GAO noted that the development of oil shale faces key challenges, including: “(1) controlling and monitoring groundwater, (2) permitting and emissions concerns associated with new power generation facilities, (3) reducing overall operating costs, (4) water consumption, and (5) land disturbance and reclamation.”

Walter Youngquist of the Colorado School of Mines provides a detailed history and analysis of attempts to develop Colorado’s oil shale. After spending billions of dollars, industry has terminated oil shale operations due to a low net energy recovery and a lack of water resources.

It is obvious now that credit for oil shale development is evaporating.

Just a few days ago there was a discussion here on TOD of EROEI for oil: http://europe.theoildrum.com/node/4757 My application of this analysis to oil shale indicates that the real EROEI for oil shale will be negative. And that explains why there will never be any credit for oil shale development.

Finally, anyone with common sense who has seen oil shale can look at the little bit of dry carbon embedded in marl rock and see this oil shale stuff "ain't goin nowhere."

This is all nonsense.

First of all EROEI can't ever be negative.

EROEI=eo/einv+1

so if the amount of Eoutput is zero and Einv is infinity

the EROEI would still be 1.

The Chinese have been producing oil shale more or less continuously since 1930, they stopped after WW2 for a couple years, they slowed production in the 1960 when the Da Qing giant oil field was discovered and stopped for a couple years in the 1990s. They produced 300000 tons of shale oil in 2007.

According to the Chinese government the cost of production is $18 per barrel. The EROEI of oil shale is between assessed at 3-10 for newer technologies.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oil_shale_extraction

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oil_shale_in_China

When petroleum production starts to decline there will be a big move to oil shale IMO.

'.... produced 300000 tons of shale oil in 2007." ~ 5000 bpd.

The estonians have also been mining oil shale very successfully.

Then why aren't we producing milions of bbls today from the oil shales majorian? More than 90% of the oil shales leases are privately owned and can had for writting a check tomorrow. I assume you mean when oil reaches a high enough sustained price there will be a big move towards oil shale. What price would that be exactly? And I guess we'll assume the western states part with all those precious water resources needed for the process. Well...I'm sure they'll do what's right for the rest of the country.

Oil shale is NOT oil, neither are tar sands.

Oil shale is not competitive with oil.

When oil is around oil shale isn't there and visa versa.

It's a different animal, more like coal.

It's measured in tons not barrels.

I don't think the oil companies will ever have the right attitude toward this resource, which will require large amounts

of energy, large amounts of land, water and capital and plenty of patience. It's a learning curve issue and the Big Oil dinosaurs are too stupid to figure it out.

All unconventional oil began as quasi-governmental ventures(Suncor supported by subsidies in the 1980s, Sasol started by SA gov't, Fushun started as a coal mine by Japan, Nazi CTL, Estonian oil shale, etc. ). The Chinese report they are producing Fushun shale oil for $20 per barrel.

In the 1960s, 33% of Red China's petroleum came from Fushun shale oil.

Then they discovered the Daqing Giant field(1960) and their shale oil production crashed, though it never stopped.

Compare Ghawar at 5 mbpd, Cantarell at 1.8 mbpd,Burgan at 1.7 mbpd versus the Syncrude mine at .35 mbpd or even the Black Thunder the world's largest coal mine at .75mboepd. You'd need

a commitment lasting decades regardless of price.

If the government decides it wants a secure source of oil it will build it.

When Cantarell disappears and Mexico becomes a net oil importer(2015), a reliable supply of US domestic oil will become a national emergency.

It's not a matter of price.

http://www.chron.com/disp/story.mpl/headline/biz/6107671.html

CTL gets you 2 barrels of FT liquids per ton of coal;

6000 kwh of coal energy producing 2 barrel (3200 kwh) of oil.

It's too wasteful.

Tar sands gets you 1 barrel of syncrude for 1.2 tons of sand;

1/6 boe of natural gas to make a barrel of syncrude. It's in Canada.

Oil shale gets you 1 barrel of shale oil plus 1/2 boe of natural gas for 3 tons of shale;1/2 boe of natural gas to make a barrel of shale oil(the natural gas product covers the oil output). Shell's method produces a million barrels per acre.

Assuming 4 barrels of water per barrel

1.8 mbpd operation would be around 468 cubic feet per second.

The 1913 vintage Los Angeles Aquaduct has a capacity of 485 cfs

and the Snake River(Jackson Lake) is about 400 miles away from oil shale deposits.

http://wsoweb.ladwp.com/Aqueduct/historyoflaa/aqueductfacts.htm

Glen Canyon Dam receives 5760000 acre feet every 60 days where 7.2 mbpd of water is 341000 acre feet per year (1.5%).

http://www.usbr.gov/dataweb/dams/az10307.htm

I note that of the known 4 trillion bbl in place of unconventional oil, only 1 trillion is in shale anyway. Looks to me like the cheap unconventional is Orinocco Heavy, and the reliable is Athabaska sands. There's at least 4 S Arabias there.

thanks lengould..

i haven't ignored unconventional oil.. this was explicitly about analysing reserves/resources of conventional oil. the two are completely different and need to be analysed in different ways.

analysing resources of unconventional oil isn't beneficial.. everybody agrees the numbers are huge. the only way is to look at how much production can be brought online over a given period. hopefully there will be a post on that in this IEA series which can then be combined with my assessment of conventional oil.

Phil,

This stuff is a real contribution to knowledge. And I was particularly impressed by the deadpan way in which you demolished the USGS discovery predictions ("clearly implausible" --- the best nice-guy euphemism for "a load of total bullshit" I've read for ages. Beautiful!).

BTW What happened to the 'Digg' button?

Digg was not dugg so the Goose stopped its use...;-)

I try to be objective, rather than appealing just to those who are already convinced, but sometimes you have to call it as you see it :-)

A very lucid analysis Phil.

I've asked a contact of mine who will be hosting Dr. Birol, to politely ask why the IEA continues to use the paper barrels in their outlook despite the obvious and recognized inconsistencies.

Peak Oil is here now, regardless of the IEA WEO report and most recent U.S. Energy Information Agency data which show some possible recent minor increase.

Global oil production has been on plateau for 4 years. When oil production is the same after 4 years of trying hard to increase it, we are at Peak Oil. With such astronomically high prices of oil all producers were pumping at maximum effort.

Just on that note: given the retreats in energy investmenst seen recently, I would think that a lot more of the remaining reserves will remain forever in the ground than was thought - the 2500 gb isn't real in that sense. The energy industry is highly capital intensive. I don't know how many blows like the current one it can withstand. So maybe there will be a few more reruns of the present crisis on the downslope, but maybe very few and not so far in between.

Like everyone else, just guessing. But we know where we are and we know where we'll end up. Just don't know the shape of the downslope. Linear? Naw. Vertical drop? Naw. Exponential dacay? Naw. Sawtooth down? Has to be, of one sort another, having excluded all else. How many teeth? A lot is not that much different from linear. Not so many and then a downward plunge as the world's infrastructure no longer can support the energy industry's ability to get ever arder to get at stuff.

I agree Dave. I've worked in the oil patch for 33 years and have lived on that saw tooth ride everday of it. In the past, the aberations we're caused by excessive production, economic down turns and growth spurts and a combination of these components. It seems we are now entering a period were those factors are still effective but have now added a new dynamic: inability to supply demand (at sustainable prices) during periods of growth in the global economy. I think it's becoming apparent that even as we slide down the PO slope we'll still experience the saw teeth. And those teeth will exact even more damage to mankind's ability to sustain itself in an orderly fashion.

Hey Rockman and Dave,

I like your saw tooth theory. The big saw tooth comes when the high price or lack of oil reduces the ability of states to maintain the highways.

[Google: state highway government budget cuts]

Then the power grid goes out and nothing modern works, including heating systems and transportation (electricity power pumps diesel and gasoline).

This will reduce the population of many cities, which provide the organization and finance for extracting and distributing energy. There could be smaller of such saw teeth when there are power grid failures in sections of the U.S. for weeks or months, or for a short duration nationally.

Another saw tooth is when gas stations are closed and people can't get to work to do the jobs required for oil or gas extraction.

When your car runs out of gasoline it stops. When the industrial machine doesn't get enough oil, something stops, and then that stops something else, I call this the "grid lock effect."

Cliff Wirth

One more sawtooth: when the cost of transportation gets so high that it is no longer worth it for a minimum wage worker to go to work.

Yes - congrats Phil - even I can follow this plain-English explanation of the situation. Angela - Dr Graham Currie in Melbourne has developed a concept of 'transport poverty' through his research into the impacts of rising transport costs on various sections of Melbourne's population. His papers are worth chasing up. Using a somewhat different p.o.v, Dodson and Sipe from Griffith Uni have done extensive research across most of Australia's major cities and regional centres to develop their own tools for assessing 'oil and mortgage vulnerability'. I've been very impressed by both these studies. Adelaide, my own home town is a city of about 1.2M residents, 95km long and about 35 wide. I understand it is about half the size of Los Angeles with about 10% or less of LA's population and (I guess) revenue base! The question for me is 'how f***ed is this city really???

Sam.

Hello TODers,

You may recall that I found the weblink to the 2002 Aramco Ghawar oil-sat graphic that Stuart Staniford, Euan Mearns, F_F, and so many others had great fun discussing.

Recently, Ghawar was massively modeled again using 258 million cells on a much larger, next-gen supercomputer cluster. If we could find this simulation, it could prove instructive on the remaining reserves of Ghawar.

Here are two links with some great detail [PDF Warnings]:

http://www.vrgeo.org/fileadmin/VRGeo/Bilder/VRGeo_Papers/article.pdf

-----------------------

From Mega-Cell to Giga-Cell Reservoir Simulation

..In an effort to build a giga-cell simulator, recently Saudi

Aramco’s scientists completed a reservoir simulation model

run for the Ghawar Arab-D reservoir using 258 million active

cells.

------------------------

http://www.spe.org/atce/2008/technical/schedule/documents/116675.pdf

-----------------------

From Mega-Cell to Giga-Cell Reservoir Simulation SPE116675

------------------------

Be sure to see the vertical reservoir slices and the new enhanced model for Abquaiq.

Bob Shaw in Phx,Az Are Humans Smarter than Yeast?

Good analysis, and this doesn't even address the "aboveground factors" that will likely result in some of what still remains in the ground being permanently left in the ground. Does anyone really believe that geopolitical factors will stay out of the way enough to enable us to get EVERYTHING out? Does anyone really believe that we'll have the money necessary (which will be huge, as this is all very expensive stuff) to get EVERYTHING out?

I don't know what discount rate to apply to your figures to account for these aboveground risks. My gut tells me that something in the range of 25-33% might not be unreasonable, but I have nothing solid to back up that gut feeling. If it is in that range, then that is bad news, for it means that there is not much volume to put under the curve on the right side of the graph, and thus that the decline will be pretty steep. - which in turn reinforces the aboveground factors in a deadly spiral.

The IEA addressed this issue in its Oil Market Report of March 2008 on page 23 and 24. This is the text I had written at that time:

Therefore the IEA takes the approach of “adjusted decline rates: