Oil, House Prices, Credit? Three parts of the same story

Posted by Phil Hart on October 27, 2008 - 9:50am in The Oil Drum: Australia/New Zealand

The long forgotten 'oil crisis' of just a few months ago has been replaced by a full blown 'credit crisis' - related events that represent the unravelling of half a century of unsustainable trends in oil consumption and debt. These two ingredients have been used in a special 'compound growth formula' to finance the construction of suburbia and fuel the (un)happy residents on their long journey to work and home again via the shopping mall, so they could spend more than their earnings on stuff to put beside the TV and inside the microwave oven.

Environmentalists have tried to teach economists a thing or two about sustainability over recent years, largely without success. However, even within the narrow world view of economists, the trends in credit growth could be clearly seen to be unsustainable (unless your name is Alan 'I made a mistake' Greenspan). That oil consumption could not grow forever comes as no surprise to a global community aware of 'peak oil', but the inevitability of oil depletion will remain hidden from economists; lost as it will be in a crisis of their own making.

The Growing Gap: Oil Imports

This is a global crisis, but the US dollar is our global currency, so the story centers on that country. Exhibit A is the growing gap since 1950 between domestic oil production in the United States and oil consumption.

Source: Energy Information Administration

Click to enlarge.

In theory of course, it is possible to produce many other 'real things' to export to the rest of the world to earn those oil imports. For three decades, the United States did that quite successfully. Oil was relatively cheap and booming domestic industries had lots to export. Eventually though, manufacturing moved overseas to developing nations where it could be done more 'efficiently'. Instead of developing other 'real things', the United States turned to credit and the power of its US dollar hegemony to keep the consumer economy ticking. Based on this next chart, I suggest that the descent into a 'fake things' economy began around 1990 when household net worth started to decline.

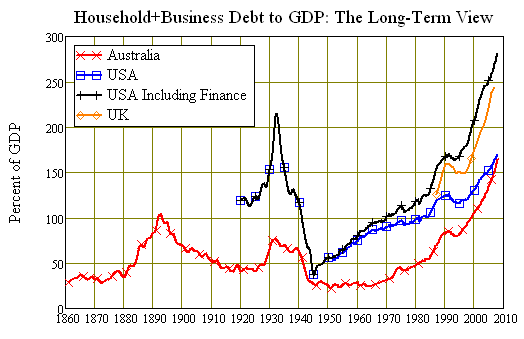

Credit: The Long Term View

Exhibit B is an even more remarkable and longer term view of the role of credit in the economy of the United States, Britain and Australia. The world has been on an incredible credit ride since as far back as 1950. The steep climb over the last ten years screams 'jump' and indeed that is what we have just done.

Source: Steve Keen at www.debtdeflation.com

For those of you asking the obvious question about what happened in Australia back in 1890, there is this paper from the Reserve Bank of Australia: Two Depressions, One Banking Collapse. The current crisis looks far more like the 1890's than the 1930's, although I find such distant historical parallels hard to comprehend at the best of times. The end of the gold standard in 1971 is also an important part of this story - a monetary system backed by gold could not have permitted such a rapid rise in fake wealth. An even more fundamental change to our system of currency may be needed to get us out of this mess and reach a true state of enlightenment and sustainability.

The link between Oil and Credit

The explanation below for how trends in oil consumption and credit are linked is taken from the ASPO USA Peak Oil Review: 20 October 2008. (You can subscribe to their weekly newsletter for free).

Commentary: Peak Oil and the Current Economic Opportunity

Richard E Vodra, CFPThe run-up to Peak Oil was a major factor in the current economic crisis, and the changes emerging from the crisis may help us deal better with the challenges of the coming decade.

The financial problems that emerged in the summer of 2007 led to the collapse of Bear Stearns in March, the nationalization of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and a cascade of subsequent events, policies, and impacts that continues as this is being written. The nature of the crisis started from the fact that the large financial institutions – banks, hedge funds, pension funds, and such – have created and used a lot of securities that are either mispriced or hard to value. They’ve taken a lot of home loans that are “sub-prime” (the borrowers had little income or wealth compared to the loan size; there was too much loan-to-value; future payments would be beyond the borrowers’ ability to pay, etc), put them together into large packages (mortgage-backed securities, or MBS), secured high ratings for the bonds (higher than the component loans justified), and sold them to domestic and foreign lenders/investors looking for high, secure yields.

At the same time, another industry was created selling “insurance” on whether these or other loans might default, and the resulting “credit default swaps” were unregulated. As long as the system worked, it worked well – as long as we kept clapping, Tinkerbell lived. The models used by the regulators, the rating agencies, and the borrowers and lenders assumed that the past records of defaults would continue. The old patterns failed, and now no one knows how much anything is worth or how big the losses will be.

I attempted to link high oil prices with the housing finance craze and early stockmarket wobbles back in August 2007. However, the links go back much further than just the last few years.

Yet while all these financial instruments were being created, there were plenty of voices pointing out that American home prices would peak in 2005 or so, and that the quality of loans was declining rapidly. According to the October 15, 2008, Washington Post, sub-prime mortgages made up 8.0 to 8.6% of all mortgages from 2001 to 2003, but 18.5 to 20.1% from 2004 to 2006. The dollar value of subprime MBS rose from $121 billion in 2002 to $401 billion in 2004 and about $500 billion in 2005 and 2006. Why the big jump in junk?

The US balance of payments deficit has grown rapidly during this decade, and one of the big drivers of that has been the rising cost of imported oil and other petroleum products. In 2002 we spent $102 billion importing oil, but that figure rose to $300 billion in 2006, and to $328 billion last year. Those imports (along with Jim Kunstler’s salad shooters and all the other things we buy) had to be financed, to the tune of $2 billion a day by last year. We convinced the Chinese, Japanese, and many others that our MBS were safe because they were sorta guaranteed (wink, wink) by Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae. We needed the oil, so we needed product to sell to finance our “addiction.” Our suppliers wanted bonds, the government deficit wasn’t large enough, so we created an endless supply of MBS to sell.

After reading this, I had to try and plot the relative scale of the growth in credit against the oil import bill (import volume times average price for each year). The resulting chart shows that the pace of credit growth has two broad periods which match the corresponding change in the oil import bill.

Source: Energy Information Administration

and Steve Keen at www.debtdeflation.com

Click to enlarge.

- Moderate credit growth in the 1950's and 60's matched the early days of slowly expanding oil imports into the United States.

- The twin oil crises of the 1970s made for a volatile oil import bill, but credit growth slowed as the economy was hit by the supply shock.

- After a recovery in the late 80's, both trends then declined during the recession of the early 1990's.

- Demonstrating the link that Richard describes above, both the U.S. oil import bill and debt (credit) have grown explosively over the last ten years.

There's little doubt that the credit curve is going to nosedive now, and for a short while at least the oil import bill may do the same.

Historically though, credit cycles change much more slowly than oil prices, the volatility of which shows up in the oil import bill particularly in the 1970's but also in the short price slump of 2000/2001. In that sense, credit growth is a heavily smoothed trend of the oil import bill - relatively steady for several decades but rising sharply over the last ten years to fund an increasing volume of increasingly expensive oil imports.

Credit growth is actually more closely correlated with the volume of oil imports, rather than the oil bill. This presumably reflects the fact that credit is expanding to match the growth in the total economy, rather than just oil prices. So oil imports are here a proxy for economic growth, which has been substantially funded by credit (debt). Both lines are zero scaled, so the proportional change in credit and oil imports has been very similar over the period since 1980.

Is the Economy Less Sensitive to an Oil Shock?

As the oil price hit $40 all the way back in 2004, warnings were sounded of economic trouble ahead. Instead, measures of GDP continued to increase leading Alan Greenspan and other 'enlightened' economists to the conclusion that our economies were less dependent on oil than they used to be and thus less vulnerable to another oil shock.

Stuart Staniford debated that point here on The Oil Drum back in 2005. His conclusion at the time was that "The only reason current events have had far less impact on the economy than the events of the 1970s is that there has been no reduction in supply!. By contrast, past oil shocks involved real 7%-10% reductions in oil supply. However, if the current tightness persists [..] the economy will be no more oil proof now than it was in the 70s".

Score 1 (of many) to Stuart. Score 0 (again) to Alan "I'm Shocked" Greenspan.

Far from being less dependent on oil now, the economy actually suffers the same disease affecting the rest of the financial sector - it is heavily leveraged. We can now turn 1 unit of oil into 2 units of economic growth, which is great on the way up. The trouble is that when oil production declines, the leverage unwinds and we get two units of economic pain for each unit of oil production decline.

Richard concludes..

Nobody – the government, the American people, the Wall Street crowd, mortgage brokers, home builders – wanted to take away the punch bowl, or look too closely at what was being produced. Rising oil import volumes multiplied by rising prices contributed to the crisis we are now experiencing.

So the housing bubble was being used to create securities (Collateralized Debt Obligations) which could be sold overseas to finance the oil import bill to keep building more houses. On the back of this, credit was expanding everywhere. The private equity boom pushing sharemarket prices further up was just another side effect of cheap credit. The risks were seen as low and just to be sure the losses were insured as well (with 'good as gold' AAA ratings to prove it).

It all worked fine until it didn't. Isn't that the economic definition of sustainable?

As oil prices started to bite, the new housing being built in distant suburbs and even more remote 'exurbs' became less viable for commuters. Once house prices started to unwind (who would have thought it could happen everywhere at once?) the game was up, but it was always only a matter of time. The United States (and now the rest of the world) could no longer find willing buyers for their 'assets' and so the global financial system could no longer expand credit to the world's consumers.

Source: US Department of Traffic: Traffic Volume Trends

and Case-Shiller Composite Housing Index.

Click to enlarge.

Global oil supplies have been all but flat for the last three years. With China and the oil producing countries still increasing their share of the pie, first the poorest and then even OECD nations were forced to reduce their consumption the only way the market knows - higher prices.

So consumers started driving less because global oil supply simply could not meet everyone's expectations. Next the value of their house fell. Finally they found the bank wouldn't (couldn't) lend them anymore money, so they stopped shopping as well. That was the last straw, as there is nothing that strikes fear into the heart of an economist more than the sight of a consumer who has stopped shopping.

Oil, House Prices, Credit? It's all part of the same story.

You can contact the author at www.philhart.com

Interesting post Phil.

For those inclined, please give this a vote on reddit :

http://www.reddit.com/r/Economics/comments/79g0b/oil_house_prices_credit...

Phil,

Thanks for the interesting article. I do not understand what you are trying to show in the last graph "Vehicle miles traveled versus house prices"?

I can accept that both have increased as debt expanded. People who live in the outer suburban regions are now stuck in these locations unless they can move in with family.Even if house prices have declined in inner city locations they have probably declined even more in the suburbs. Also new buyers will still find suburban houses more affordable even with rising fuel prices. Thus they will still need to commute if they have jobs, but may do so in a smaller less expensive vehicle and may drive less non-essential trips.

The argument that the 2008 economy was less sensitive to oil prices was based on the lower oil intensity of the economy than in 1980. That is still true, vehicles have higher fuel economy(25mpg versus 12mpg), but VMT has also doubled. I would suspect that more of to-days VMT are non-essential compared with 1980, so we should see a much larger reduction in gasoline consumption relative to overall GDP.

The conventional wisdom is that this financial crisis is a result of a housing bubble in the United States. While that is true, it is also a result of limits to oil supply being reached. So in this article, and particularly in the final graph, I'm showing that the decline in the availability of oil to drive vehicles is linked to the decline in house prices.

Phil,

I think a lot of TOD readers would agree with your hypothesis that high oil prices have contributed to financial stress and accelerated house foreclosures. If this is true we would expect a rebound in VMT( not necessarily gasoline consumption) and a rebound in house prices. If the financial crisis is unconnected with high oil prices, we may see a rebound in VMT but a continued decline in house prices, until effective(inflation adjusted) interest rates are negative. I think its too early to draw any correlations.

If the average family household income is $50,000, and that family has two vehicles each using 500 gallons, then a price rise from $2 to $4 a gallon is going to cost that household an extra $2,000. The other "transportation" costs are financing of vehicles, depreciation and repairs, and public transport which probably account for more than the cost of gasoline. A 4% interest rate rise on a $150,000 sub-prime mortgage would cost that household an extra $6,000. It could be that the two increases together tipped these households over the edge, but most households do not have sub-prime mortgages, but do drive, so the sub-prime rate rises are large and concentrated on only a small proportion of households. The fact that the US economy only started to decline in last few months, while housing has been in decline for a year indicates that the US is having a housing induced recession, that has spread the the rest of the economy, not an oil induced recession, but cannot say what would have happened if oil prices had declined last year instead of increasing.

Your statement; "The trouble is that when oil production declines, the leverage unwinds and we get two units of economic pain for each unit of oil production decline" doesn't make sense, a less oil intensive economy would not "unwind" to become more oil intensive with rising oil prices, but would become even more less oil intensive.

I definitely do not expect a rebound in vehicle miles anytime soon! Lower oil prices may help alleviate some of the pain, but they won't be anywhere near enough to help the economy recover in the short term.

The credit financing for the enormous 'fake wealth' economy has now collapsed. Oil prices may stay low but expanding credit which was driving the economy has vanished so there will be no quick recovery. I'm not so worried about what is correlation and what is cause over the last few years. The housing bubble was unsustainable in it's own right - the slope on the final graph should make that clear. High oil prices leading to reduced travel was the pin that popped the bubble, but it couldn't have gone on much longer anyway.

My point is more about the longer term. The expanding credit cycle has lasted fifty years and was related to oil imports. That cycle is now over. The United States and much of the OECD world is going to need to find a more sustainable way of paying for its oil supplies in future.

A clear and succinct analysis Phil. Oddly the current meltdown doesn’t feel so unique to me. I moved to Houston in 1978 at the beginning of the oil boom. Of course, this was a period of “oil shock” for the rest of the country. In retrospect that period locally has many similarities with the national trends of the last 10 to 15 years: rapid economic growth, low unemployment, very easy credit (all you had to do was put “Oil Industry” employment on the app and you got a $10,000 unsecured limit on any number of credit cards), rapidly escalating home values with easily obtained mortgages (even with mortgage rates hitting 16%), strong infrastructure growth and a tremendous rush towards the suburbs.

Then there was the local bust in the 80’s which mimicked many of the current negative trends. In the sense that you describe, Houston was highly leveraged by high oil prices as was the national economy leveraged by low energy costs. The huge drop in home valuations coupled with crushing high end unemployment (favorite joke at the time: home many geologist can you fit in the back of a pickup: two…you have to leave room for the lawn mowers) delivered just as bleak future as we now see for the nation as a whole. Houston did survive, of course, but it took every bit of 10+ years to recover to any significant degree. Excluding agriculture, Houston’s economic history could serve as a model for the nation’s current ills. Some big differences though: Houston didn’t have the Feds trying to bail it out (a double edged sword) nor was the world pushed into a recession. Just the opposite: $10 oil in 1986 can be defined as the beginning of this last national/global boom IMO. It’s difficult to imagine current ills being corrected any quicker than Houston recovered. In fact, a 15+ year time frame seems more reasonable.

And, true to the cyclic nature of commodities, Houston’s boom continues today. How long it will continue to do so will again depend on how long oil prices stay low.

The whole energy intensity measure is flawed mightily. It uses GDP in the denominator and that is the flaw. GDP is a horrible measure of the economy since it includes all dollar transactions as income. It does not correct for maintenance and defensive spending such as repairs from hurricane Katrina or the military budget. It is not a measure of the health of the economy; most economists know this, but argue we haven't got anything better.

Then consider that we now claim to have a service economy. If you take a hard look at what these so-called services entail you discover that most of them are just moving paper (or bits) around from one place to another. Or they involve fast food and broker services. Each of these kinds of jobs involves far less energy consumption than, say, automaking. These are the jobs that have accounted for most of the growth over the last twenty years or so. I'm betting that the growth of the service sector will go a long way to explain the reduction in energy intensity. Use a corrected GDP and I bet most of this so-called efficiency disappears. Actually I bet a lot of the so-called growth disappears as well.

Question Everything

George

George Mobus:

Energy efficiency is a tricky thing. Alone, it will not solve our problems. As our economy has grown more energy efficient, energy consumption has risen - contrary to what the New York Times continuously advocates. Look at this chart from the EIA:

www.eia.doe.gov/pub/international/iealf/tablee1g.xls

Our btu's per dollar gdp has dropped significantly, yet energy consumption is rising - the EIA expects these trends to continue. This situation is even more interesting in the automobile sector.

A recent study by the National Commission on Energy Policy examined the federal mandate for automakers to meet certain efficiency targets, the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFÉ) standard. The Commission found that even if Congress forced the U.S. auto fleet to raise its average fuel economy from 27.5 to 44 miles per gallon (a massive increase of 60%), fuel consumption would still jump by nearly 4 million barrels of oil per day by 2025. The Jevons Paradox at work.

Well understood in modern economics, the Jevons Paradox is a very important concept when it comes to energy efficiency. William Jevons first described the phenomena in his 1865 book, The Coal Question. Increasing the efficiency with which a resource is used tends to increase (not decrease) the rate of consumption of that particular resource.

Jevons first discovered the idea after observing England's consumption of coal soon soared after James Watt introduced his coal-fired steam engine, which greatly improved the efficiency of the previous design by Thomas Newcomen.

What this really means is we need "all of the above" approach that McCain discusses. We need more energy solutions such as clean coal, EOR, CCS, etc.

Which all assumes that demand reduction is impossible.

By which reasoning, Melbourne and Brisbane's reduction of water consumption which has happened over the last decade was impossible, and that we should still have most people being smokers, and the Chinese should still have a big opium problem.

Efficiency goes up -> cost goes down -> usage goes up

That can be attacked in the middle, with cost. Peak oil by itself could do some of that, the state of the economy could increase the relative cost vs. income, and carbon taxes could increase the cost (capturing what would otherwise go to an oil company windfall).

While there is obvious interconnections between the different markets, I don't think there is much of an energy component to the current credit problem, outside of the damage done to investors by the whipsawing prices in the oil and other commodity markets.

This is probably a greater problem than a reading of Mr. Hart's article would suggest.

I suspect that long term flat or declining real wages and long term suppressed yield are behind the credit mess. Declining comparative wages left workers unable to afford housing without resorting to exotic credit which was magnified up the credit distribution chain by poor underwriting and risk management - the willful suspension of disbelief. Low wages and low yields conspired to reduce savings which left credit as the most accessible and least responsible form of capital. Low yields and the accompanying flood of liquidity translated to cheap lending which had increased amounts of capital chasing fewer acceptable investments.

The result has been a capture by the credit system of both current wages and wages well into the future. (Savings being considered past wages, aggregated.) When it became clear a couple of years ago that the future wages available were inadequate to service the corresponding liabilities, the system broke down.

When it becomes apparant to our overseas creditors that future growth will be inadequate to service the corresponding liabilities, the international system of credit will also break down.

Since both problems are structural and driven in exactly the wrong direction by both prejudice and public policy, the likelihood of a 'quick fix' - less than several years - is exactly nil.

The implications are sobering because this suggests the full weight of energy supply difficiencies lie in the future, after the credit system's deconstruction has accelerated. With some credit availabile there would be the possibility that some number of petro- alternatives could be brought into service rapidly, paid for by captured future earnings. With the credit dislocating and the likelihood that the US government's credibility and competence will be questioned, the difficulties of gaining the trust of creditors in any financial marketplace will be large indeed.

Further weighing on credit are the derivative/swaps originations. The fallout from the credit malfunction has just begun to ripple through the swaps and counterparty markets. The potential liabilities are stupendous and the consequences ... applying to the central concepts of 'market management', 'government responsibility' and 'authority' ... are possibly severe.

... then, Antarctica melts and the Cubs win the World Series.

It's actually pretty amazing that our foreign creditors have not already caught on. Old flight-to-safety habits die much harder than I would have thought.

fat_tail_rider

I disagree with these assumptions - primarily that house prices and VMT must remain correlated. Given that house prices were totally artificially stimulated via central bank policies intended to do exactly that, a return of VMT may not mean a returning rise of house prices. House prices could remain severely depressed while workers return to work, choosing to rent as existing housing stock is absorbed back into the economy at distressed pricing.

Correlation does not imply causation. A rise in VMT may not cause a rise in house prices, even though the price of fuel is currently fairly low.

VMT are just a proxy statistics for consumer oil consumption. It is an indicator of how rising oil prices impacts the consumer.

The correct causation is similar to the pressure on a wooden stick that broke it. The inflation from high energy price is the pressure. The credit system collapse is the wooden stick breaking. Releasing the pressure does not glue the stick back. Broken it is, broken it remains. Oil prices, VMT and housing prices do not have to remain correlated because the collapse of the credit is a discontinuity in the economic system.

What I wonder is, since oil price has gone down so much, have we seen (or are we starting to see) any signs that the dip in driving (as proxy for oil consumption) is being reversed back into an uptrend now?

I believe some here on TOD have commented anecdotally that "SUV" are again in more demand. Other signs?

Memmel has a good and very elaborated post on VMT under this very article. He brings a convincing argument that we should be at the bottom of it. Search for Memmel's posts for details.

I posted a link to that.

Overall I think we will simply flatten out with VMT not going down nor going up.

It might trend slowly up with population growth but even thats debatable at least for a few years. Historically the VMT in depressed regions remains flat per capita.

Farther out as the Baby boomers retire assuming we have not collapsed I think that the combination of retiring boomers and oil prices finally reaching the point of real pain i.e 10-15% of income we will actually see declines.

A short rant. Its been assumed that high oil prices lead to the recent collapse in demand. The decline in VMT however follows closer to housing thus and I have tons of articles which show VMT is not correlated with the price of oil but with general recessions regardless of the price of oil. This does not mean that expensive oil does not spark the recession but actual decline only happen once the economy starts declining overall. For the housing lead bubble this started in 2005 and VMT increased the years before the bust of the housing bubble and oil prices continued to increase even as VMT decreased post housing bubble burst.

We did not actually hit the point that VMT was directly declining because of high Oil prices. Thus it seems to make sense that this is in the future and happens only after we have had a stagnant economy and flat VMT and reach the point that we don't have enough oil to support this and prices have risen to a onerous level. Thus the direct coupling is only after we have had my flat bubble.

Wrong VMT is not correlated with oil prices. This has been shown many times.

VMT is correlated with overall economic growth and so is housing.

The link between high oil prices and VMT is indirect. Our recent growth was in housing as oil prices roses and housing rose we had to drive but did not have to buy a new house

thus the consumer pulled back on spending for a new house. The housing bubble popped first oil prices kept increasing and VMT turned down in 2006.

Its a bit of a who's on first game but regardless the combination eventually resulted in the consumer unable to afford the rapid appreciation in house prices.

In any case the correlation is between VMT to growth and growth to housing construction. High oil prices are secondary and acted as part of the break on the housing bubble. As this article points out flow of funds and oil imports plays a bigger role over the long term irrespective of the actual price of oil.

The debt bubble is correlated to rising imports not price per barrel. Until recently we could always increase the amount of debt to cover either a per barrel increase in price or a increased need for imports. Serial bubble blowing in various asset classes hid the inflation as nominal growth. The reality was simply certain assets became overpriced for no fundamental reason injecting "wealth" into the economy and keeping the game going. Housing just happened to be the most recent bubble.

In one of my long posts on this thread I identify the effective move to socialism and direct capitol injections into companies as the next bubble that is forming to keep the game going.

Any day now the correlation will then jump off the popped housing bubble and on to the size of cash injections into the economy made by the Fed. The more money injected the more VMT will increase. Viola a new bubble and happy times again. This will reignite the commodities bubble.

But note this is the last bubble possible since once all the governments start printing and taking on failed debt your headed towards sovereign currency defaults.

So in the last bubble possible we will see nation after nation default on debt. Iceland is the first but won't be the last. Argentina looks ready to do it again.

Eventually of course the US will either hyperinflate or default.

In fact if we can get some good stats on the cash injections by the various government s we should be able to show VMT becoming uncorrelated with the moribund housing market and become correlated with the direct injections. They are using so many different ways to inject cash however that its almost impossible to track. My best guess as far is tracking it would be US Treasuries and VMT will become correlated in some fashion as Government Debt explodes.

The Bank of England is coming out with some estimates on the losses incurred so far:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/financetopics/recession/3269827/Toxic...

The UK authorities are to try to maintain borrowings at near the peak level in 2007 by capitalising the banks and enforcing lending - God knows how they imagine it will ever be paid back.

Thats my point they won't. I'd be surprised to see the Fed as forthcoming as the Bank of England with a grand total :)

Thats why this is the last of the bubbles. Fiat currencies always eventually die inflated away. We probably will continue to see asset deflation across a broad range of asset classes even with this last bubble. I think it will be like Japan in that sense esp for anything that requires long term debt.

My understanding is that Japanese wages have been flat despite the enormous amount of debt taken on by the Government.

http://www-econ.stanford.edu/faculty/workp/swp06009.pdf

For this and a host of other reasons we can expect wages to probably remain flat and thus tax revenue flat. Maybe at some point the US government will start setting high minimum wages for various occupations dunno.

In any case lets not forget peak oil since any actual inflation will probably result in higher oil prices so I think this great last bubble will end fairly quickly as the link between debt and oil imports becomes blatant and unavoidable.

Also as far as I know this will be the first time the entire world goes on a printing spree at the same time because of globalization.

Its one last grand experiment. My best guess is that this will be intertwined with attempts to decouple economies and strengthen internal demand as exports of goods become problematic. Asia for example probably will allow their currencies to appreciate vs others this would support running the printing presses.

So for the Yen for example I suspect we can see a reversal of policy and Japan start allowing the Yen to rise to allow it to print and spur further internal economic development.

The US has of course pulled of the big one with the recent strengthening of the dollar its in position to do some serious inflationary printing for free.

The key point is I think that the blocking point is how much debt our outright printing can be done before required imports like oil get to expensive in the local currency. I think we will finally eventually see all the fiat currencies finally come to the same value i.e zero.

In any case its hard to figure but right now the world has decided to allow the US to print trillions and still have its currency increase in value. And amazing feat and one that can't last forever.

I see why Don Sailorman is 50% deflation and 50% inflation for the future. I think its just a matter of how much each country can get away with before commodity prices stall the ability to print.

As this thread shows good chance that this played a key role in popping the last printing bubble so it stands to reason it will pop the next one.

But as you noticed this effectively means the worlds governments will default ala the Soviet Union.

Regardless given the existing debt loads from our last bubble I only give this socializing of debts a few years say four at most before it blows up.

For example its good to read about the last time we bubbled.

http://www.financialsense.com/stormwatch/oldupdates/2002/0412.html

We now know the housing bubble pulled us out.

Look like government debt pulls us out of this one.

However given that we will have less energy every year all that can happen is blowing one more bubble all this money can't go into anything useful since we simply don't have enough energy to expand any part of the economy that uses energy.

The final ruse of course has still yet to be done but its probably coming once everyon e starts printing and fiat currencies imploding as the government default the one last trick left is a world wide currency. Everyone converts to this erasing existing government debt and we have the real last blast.

I'm wondering how this will be pulled off sense its useless unless the debt is defaulted. I guess the trick will be the new currency is created then a Government defaults and is "switched" over each in turn until all are converted.

It makes sense then to concentrate all debt into the government first before switching so it can be defaulted on or hyper-inflated away. We have had hints that a new currency is already on the agenda.

I go along with a lot of what you say. However, I think that perhaps you are assuming links are very tight in some things when that may not be the case.

To enumerate:

Peak oil is not the same as peak energy.

Now your contention is that they are effectively the same thing, as ever-reducing EROI will increase all energy costs, not just oil. I would agree that there is a tendency for the EROI of many other energy sources to drop, but the timescales are unclear, and what is more they vary from region to region.

For instance, in the US it would appear that they will be able to continue their distressing practise of mountain top removal in West Virginia for some time to provide coal, and reserves of coal in many other regions, at admittedly lower EROI than is traditional are vast, and so some sort of plateau may occur in many regions of the world for many years.

Both advanced nuclear power and renewables display the opposite to the characteristics you describe, as they are likely to get more efficient in resource use over time, not less, and some sort of plateau in fossil fuel production might allow time to develop them.

In the case of wind, for instance, new 7.5MW turbines would be more efficient than the old.

In the case of nuclear, the barriers to building more efficient reactors have been primarily regulatory.

If not in the US, then in many regions of the world shortages and hardship are likely to result in some pretty drastic measures to ensure speedy authorisation.

Similarly I find your arguments for the inefficacy of energy conservation less than conclusive.

If one assume that you are correct, and to date energy conservation has done very little to improve the ratio of production to energy, that was in a very different context.

Energy has been a relatively cheap input for many years, and so the incentive to economise has been limited.

This can be seen in common experience.

Where energy is cheap, there is little incentive to insulate.

It would also appear to make a difference how some of these printed dollars, yen and so on are employed.

You are correct that Japan's roads to nowhere have done very little to turn the economy round.

But is we hypothesise that the public works programs are devoted to building rail, to building renewables and nuclear power, to insulating, and to altering the sewage and agricultural cycles to reclaim nutrients, then the least we can say is that the outcome from such policies would be preferable to if they were just frivolously thrown away.

Things are pretty bleak, and there is certainly no way of continuing BAU, but it seems to me that very different outcomes will obtain depending on how this last bubble is deployed.

Thanks for a fine analysis.

Well coal is not evenly distributed and not nearly as fungible as oil so its story is different and more complex. To look at and example of what I'm talking about you can look at Europe and the mass migration to America in the 1800's as the European debt/EROEI pyramid collapsed.

Next as far as renewables what people ignore is that not only would they have to replace our current energy sources but they would also have to pay off the immense debt pyramid we have created. Its a two part problem. You have to solve both to transform a society.

In retrospect its clear we would have had to make a concerted effort to move to renewable/alternative energy and not initiated the final debt bubble of the 1990's to effectively move to renewables without disrupting the status quo.

And this does not include the miss-allocation of resources issues from both suburban expansion and from the distorted global trade imbalances.

We have two problems to solve 30 years of piling on debt worldwide and ever less more expensive energy. Today in my opinion the debt problem has probably overshadowed the original reason for the debt declining EROEI. Furthermore given that we have even more distortions such as that the energy consumers print the money used to pay for energy i.e the petrodollar you have to deal with the intrinsic structure of the banking system thats unfavorable to renewable energy.

So in short you really have to show how renewable energy can beat the system and last but not least increase the flow of capitol to the wealthiest individuals no solution is viable if it interferes with the concentration of wealth even if it offers long term gains.

Obviously I feel that today the deck is heavily stacked against renewables and will remain so until we default on our impossible debt load. We probably will rebuild our economies using renwables and nuclear but we won't build a new economy on them.

Lower EROEI Oil can't even solve our problems so I don't see renewable's as useful for our current economy.

"the mass migration to America in the 1800's as the European debt/EROEI pyramid collapsed."

Could you elaborate on that? I haven't heard anything about that.

http://www.let.leidenuniv.nl/history/migration/chapter52.html

Enclosure or taking over the commons.

http://www.eh-resources.org/timeline/timeline_transformation.html

http://www.eh-resources.org/wood.html

Basically what happend in europe in general was a shortage of wood and charcoal and clearing of forest for farming and a shortage of food.

The old fashioned farming methods not all that different from the ones of the Middle ages. In general a Middle ages agricultural community was supporting the new industrialization not to mention numerous wars and a rapped expansion of population.

Although coal usage was certainly increasing esp in the cities 18'th century farming was in dire straits and starved for just about everything.

The mass migration to America is probably the only thing that prevented the outright collapse of 18'th century Europe. This coupled with the flow of resources back to Europe allowed it to industrialize.

The industrial revolution and switch to coal would have almost certainly failed without the resources of America and use of a America as a way to offload excess population.

A good lead up to the period.

http://www.econ.ubc.ca/dp9814.pdf

To a large extent this transition period has been glorified in the history books and the fact we barely pulled it off is ignored.

Whats really interesting is the argument is made that the transition from wood to coal was a transition from a lower value energy resource to a higher value one.

http://hypertextbook.com/physics/matter/energy-chemical/

But Charcoal is 29 MJ/kg vs

coal, bituminous > 23.9 and

coal, anthracite 31.4

The change in direct energy density is to close to be of consequence and worse coal production took dedicated labor and had its own EROEI.

Charcoal manufacture could readily be interleaved with other jobs or made by fairly low energy dedicated labors.

The move to coal from wood and charcoal was probably a net loss in EROEI !

A good article on this and previous wood shortages.

http://www.energybulletin.net/node/10128

Needless to say this is not the first time that civilization has hit the EROEI wall.

Well, thanks for the detailed answer - I don't have the time to digest it in detail right now, but I'll try to soon.

It's truly amazing to me how good some of these comments are. So many brains to pick, so little time. TOD is like a small version of cloud computing!! Every morning I get up well before dawn to see what shoe has dropped and how that particular shoe might link to this current discussion of VMT, PO supply/demand, deflation, inflation, fiat currencies etc. Today's shoe appears to be a recognition of worldwide credit and currency collapse and European bank losses from immense lending to emerging markets in Eastern Europe,Russia, Latin America and Asia. These losses may end up being several orders of magnitude worse than the sub prime CDO scam we foisted on the world. The BIS lists loans of $4.7 Trillion to these markets with European banks holding over 70%. If you look at the losses as a percentage of each country's GDP, make sure you are sitting down: 50% for Switzerland for example and roughly 25% for Germany, Spain, Sweden yet the good ole US of A is only 4% of GDP. We have other ways to lose money than loaning money to emerging economies apparently. The same BIS website has estimated numbers for the various derivatives which is almost beyond comprehension, in the hundreds of trillions. IMO, the level of worldwide debt and credit extended in the past decade will make it impossible for the recipients of this debt ever to repay it. This the Panic of 2008 will dwarf any of the panics of the last 200 years. And then along comes the consequences of PO......Growth will stagnate and then enter inexorable decline and we wont have laid track, or built reactors or rebuilt the grid. Darn.

"worldwide credit and currency collapse and European bank losses from immense lending to emerging markets in Eastern Europe,Russia, Latin America and Asia...may end up being several orders of magnitude worse than the sub prime CDO scam...The BIS lists loans of $4.7 Trillion to these markets with European banks holding over 70%...50% for Switzerland for example and roughly 25% for Germany, Spain, Sweden yet the good ole US of A is only 4% of GDP. "

Could you provide a source for this, or more information of some sort? I haven't seen this elsewhere...

It is from the Bank of International Settlement figures, which have been reported in a number of places:

http://www.finfacts.com/irishfinancenews/article_1015088.shtml

The exposure of the UK to Asian emerging markets is also notable.

You're right. The magnitude and complexity of the global debt created and flung into the works of everything make it impossible for it all ever to be rightly valued let alone all paid back with interest. That's why I suspect that at some point in the evolving mess, a global Jubilee will be declared - a nulling and voiding of all debts and currencies with a totally new money system.

You must have misread me. I never meant to correlate VMT with oil prices. I meant the very logical equation:

miles traveled * price per mile = cost of travel fuel

In other words I meant that when the price of oil increase, the cost of high VMT increase as well and people grow unable to pay for housing. As a result the bubble popped.

Reading back the thread, I think I must have misread Greyzone. I thought he argued that VMT and housing must remain correlated when he argued the opposite. My bad.

Thanks for the explanation anyway. It brought into light many details of your thinking that had otherwise escaped me.

Having read Mish Shedlock and others, I wonder if this particular bubble will be stillborn. The point of capital injection is to restart the credit bubble again but there is a shortage of solvent borrowers.

----------------

Edit

Memmel,

I went back to read the post where you describe the new bubble. It is different from the recapitalisation of banks that is going on. You think of sort of massive subsidies to all kind of companies to keep production going.

Where will be the buyers for this production? If there is a shortage of solvent borrowers for credit, won't there be a shortage of buyers of subsidized goods? Or will the government have to channel the funds through the buyers to ensure transactions occur?

In any event if government is to print money for company subsidies, they should subsidize a transition off oil. The economy may still go bust, but at least we get a chance to get out of the poor EROI vicious circle in the process.

True and as you noticed they are giving the money to banks not directly to people.

The Banks will use the money to but other banks not lend money. The money will go directly to businesses so layoffs will be low. AIG is just the tip of the iceberg.

My best guess is that as long as your not doing subsidized long term loans for houses and cars or even if you our the buyers are the employees of the companies and their wages are the subsidies so they continue to be able to purchase a lot of goods.

Maybe I should make this clear without intervention our economy would have collapsed completely over the last weeks. A big part of this bubble is like a iceberg mainly hidden the bubble is more a not collapsing then probably our last bubble.

Literally just being able to do BAU is a bubble these days !

But BAU will run smack into peak oil as the short term collapse of housing fades and depletion lowers oil production.

So I think our next bubble will be one of static to slightly growing GDP with continuous cash injections keeping all kinds of businesses going that should have collapsed and with Peak oil causing commodities to increase in cost necessitating even more case injections to keep these ever more useless businesses functioning.

Outside of commodities I see the price of most goods to be flat or falling as you note no one actually gets credit so they can afford them. Consumers are moving to cash.

This means guess what inputs will cost more than they make and the loss will need even more subsidies and cash injections !

The next bubble is like the .com bubble but on a larger scale. Everyone will be selling for a loss and making it up in Volume with the Gov acting like a mega hedge fund.

Will we get actual growth ?

I doubt it Japan could not and I don't see why the US will what we will get is a land full of dysfunctional companies with bloated payrolls. Also I'm sure the Government will soon be bailing out states and then local governments starting with California so you will keep a lot of the fat thats in State and local governments.

Mish is expecting the unemployment rate to soar I agree it will go up but doubt it will go over 10%. What you will see however is companies trying to make it without government assistance esp if they compete with those that are on the dole go out of business. As you have noticed so far this money is not being equably distributed as it starts to take over it will distort our economy into the traditional state run economies.

And last but not least all this has to happen with less and less oil.

Ohh and as far as supporting a transition off oil. One can only hope however I doubt it in the short term only once it becomes obvious that this last bubble is just resulting in high oil prices will they eventually figure out the obvious and try to support moving off of oil. However I'd be surprised if we last that long. I think the US government can easily pump trillions of dollars into the status quo and keep it moving along even as oil prices increase.

Also politically supporting moving off of oil or the car economy means job losses in existing industries so change under this sort of socialistic economy is even harder then it is today and today its close to impossible.

But again I just don't think we have the time left for all this to play out. I think that the pumping that just keeps the economy afloat coupled with China and India pumping to keep theirs slightly growing will be enough to send oil prices climbing if we are really now in actual decline in production not just a plateau.

Don't forget that under the covers population is still increasing many of the worlds economies are still actually growing the world probably still experienced overall growth this year. Supply will quickly not meet the demand of even what I'm describing.

Whats ironic is its actually the steady state economy that a lot of people talk about but done exactly the wrong way.

Memmel,

What you describe is a totally broken nightmare.

I can't imagine governments incompetent enough to pull this stunt without knowing it is doomed from the get go. Maybe they will be desperate enough to try it anyway, but I don't expect the media to let it happen without saying it is crazy. I also expect every opposition party to ridicule any government that dare doing this. I guess that should make it a political no go.

LOL

You must have missed the blank check congress gave Paulson recently.

Your a bit late but welcome to the party.

Mish

http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com/

And CR and Tanta

http://calculatedrisk.blogspot.com/

Are doing a good job documenting this.

Example

http://calculatedrisk.blogspot.com/2008/10/wsj-gm-may-get-5-billion-loan...

The problem at the moment is keeping track of all the money flowing out in bailouts

through all the numerous channels.

Don't forget that the Fed now accept stinky tennis shoes as collateral for short term loans you can roll these loans and a rolling loans gathers no defaults.

So some of the bailouts are hidden behind loans on worthless collateral.

Its not just obvious bailout money.

To be honest I've lost track esp with all the CB's getting into the bailout game.

I did not miss the blank check. Congress would rather have a root canal than grant one of those as we saw. This stunt won't be easy to repeat.

I visit Mish and CR a lot nowadays. I also visit Financial Sense. I see the printing press going on. They are running around with hand held fire extinguishers because they don't have a fire truck suited for the task. For the moment political oppositions let the governments do the running in hope that this somehow ends up working. But at some point the futility of it will be apparent to all. Then the ability of leaders to stay in charge will collapse.

This blank check given to Paulson has a cap on it. Even for the apparent target purpose of recapitalizing banks this blank check isn't barely enough. Even those hidden bailouts you refer to are not enough. All the monopoly money they are printing is disappearing into a black hole that serves only to erase the paper losses of toxic securities and fund the merge of dying corporations. I didn't count but my impression is they will need to increase these funds by an order of magnitude or two to complete that job. Then they will need at least to double that amount to do what you say they will do. This is just the US. More printed money will be needed globally.

Also what they promised Congress they would do and what they actually do are two different things. The cap on the blank check was there to ensure some accountability would occur at some point. By definition the political class is filled with clan divisions that are rivals for power. If those gaming the system can't produce results, something is bound to backfire... or worse. I think political unrest is much more likely than the scenario you described because such scenario is not politically sustainable.

I wouldn't hold your breath waiting for political unrest in the USA-Obama is marketed as a change and he works for Robert Rubin. There is no viable third party/political alternative.

It looks like I need to clarify myself.

The political class is divided into clans that vie for power. This competition is not on friendly terms. If one group makes himself vulnerable, the others will stab him in the back. I was arguing the next bubble envisioned by memmel is a political no go because because it is a conspicuous absurdity. Any politician trying this stunt would make himself an easy target for such backstabbing. I don't expect politicians to go for political suicide. This has nothing to do with bringing into office a viable alternative.

I think it is more likely that politicians fail to deliver any illusion of prosperity after trying something that superficially looks plausible but is ineffective in reality. This avoids immediate political suicide and has the dubious merit of buying the politicians some time. Therefore I think it is quite possible that after a bit of such ineffectual policies impoverished workers to start demonstrating or perhaps rioting. This is the political unrest I have in mind. Again this has nothing to do with bringing into office a viable alternative.

Actually, house prices climbed dramatically between 1998 and 2006 only because cheap and easy credit bridged the gap between real wages and escalating house prices. Assuming the days of easy credit are over, either disposable income must rise dramatically (not likely), or house prices must continue to fall until they are in balance with more traditional mortgage qualifying ratios (+/- 28% - 31% of Adjusted gross income). This graph suggests house prices still have a long way to fall.

Median New Home Prices vs Median Household Disposable Income

The situation requires even greater falls than that, as the initial fall will lead to greater job insecurity which will throw at least one of many households out of work, and so the reversion is likely to be to a multiple of 2.5-3 times main income winner, rather than joint incomes.

This in turn means that the bail-out of the banking system is not based on realistic figures, as the security behind most bank loans is far worse than allowed for even in the case of the proportionally much greater UK bail-out.

The only thing which might sustain house prices would be very fast inflation, but I doubt that in the UK almost certainly and in the US probably the authorities will be able to get away with issuing currency on the scale required without provoking a total collapse in the currency and credit rating of the country.

I see things happening a lot faster than some believe, on the scale of weeks or months rather than years, as dominoes are falling over at an accelerating rate.

Stock exchanges are still grossly overvalued, with 3000 more realistic for the DOW.

... and also because of, in a $13.3 trillion economy,

- US public debts of $9.3 trillion (prior to bailout)

- non-bank commercial debts of $10.1 trillion

- $2.6 trillion credit card debt (42% of Americans making minimum or no payments on their credit card debts)

- unfunded Medicare and Social Security liabilities of $42 trillion

... and of all this US debt, $13.7 trillion of it is owed to foreign companies or governments - possibly something to do with the $700 billion trade deficit.

And then there's the Defense Department spending of $515 billion, plus $23.4 billion for nuclear warheads (goes into the Dept of Energy budget), about another $250 billion in the wars in Iraq/Afghanistan and other discretionary spending which are not counted in the regular DoD budget... it costs a lot more to lose a war than it used to! Nor is the $74 billion of the Dept of Veteran's Affairs counted in the DoD budget... and we can expect this amount to rise a lot as the US cares for its maimed soldiers.

And then there is growing unemployment in the US, too, and a growing rich-poor gap, which inevitably leads to growing civil conflict - crime or guerilla warfare, or a bit of both, there are attacks on oil and gas pipelines in Canada so perhaps we'll see something like that spread south?

The situation is well-expressed by a Russian who like Dmitry Orlov is familiar with the signs of a Great Power's collapse.

If it weren't subprime mortgages or oil, it'd have been something else. Given how noisy and often hysterical Americans are, we forget just how tired and weak their country really has made itself - it has many fundamental strengths in its vast size and natural resources and many educated and hardworking people - but they've done their best to undermine them. The US is like some old old man who's been bed-ridden in a nursing home for thirty years. He has diabetes, heart disease, emphysema, renal failure, arthritis, glaucoma, and stomach cancer. Pointing to a definite cause of death will be difficult.

i would have uprated you if you hadnt bugged my room and peeked at my medical records.

If you believe the reasons for war given on TV, then yes they were lost. I do not believe the reasons for war given on TV. The wars are to establish and maintain a network of military bases in the Middle East, near where the oil is, before peak oil became too obvious. Afghanistan is also about the heroin trade. These objectives were met.

I don't think anyone in power seriously believed that the wars were about establishing peaceful pro-USA democracies, like post WWII Japan and Germany have been. If you read PNAC you will see no such plans.

In the beginning of the war on Iraq, when US troops guarded only Baghdad's Oil Ministry, everything else was looted by organized mobs. Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld explained:

I didn't say that the wars were to establish pro-US democracies. After all, those two things don't always go together - what if the people elect an anti-US government? Or not even anti-US, just a government telling the US to leave forever? "Thanks, we'll take it from here."

Obviously the war against Iraq was about oil. However, they're losing it because they don't control the oil. Lots get bunkered by the insurgents and criminal gangs (sometimes both, insurgents have to fund themselves somehow!), foreign contractors and Iraqis both corruptly siphon some away for themselves, and a good part of the rest is stopped by pipelines being blown up and the like. And then of course there's plain old rusting and other corrosion in pipelines and refineries since Iraq has been at war or under blockade since 1979, so things got worn down.

Thus, as an attempt to secure a reliable oil supply for the US, the war against Iraq has been a failure.

I don't hold to conspiracy theories about Afghanistan being a desire to control the heroin trade, or the two wars being a deliberate attempt at creating chaos in the world, etc. We shouldn't mistake incompetence for malice. If a man ploughs his car into a crowd waiting at a bus stop, it's not necessarily murder - usually he's just a really crappy driver.

Very fine and detailed post, Phil. Many superb comments but the winner is Kiashu for his detailed data filled thoughts. The huge total US debt is the big stunner and 13.7 trillion being held by foreigners is the fragile pillar holding up our happy motoring card house. Barrons carried a story of Taiwan moving to reduce agency and treasury debt ASAP. In July 2007 they held $55 Billion in agency debt and $43 billion in treasuries, a fraction of its bigger brother across the Taiwan Straits. An article in seekingalpha cites an article in the chinaspeople's daily calling for "banishing" the US dollar from direct trade relations:http://seekingalpha.com/author/edward-harrison.

I could not find that statement but if true , we could be in a world of pain very soon. But today's issue also states that Chinese baby formula is safe, so take it for what it's worth.. Most TOD ers "know" a few things: 1. Rapid US postwar economic growth was facilitated by cheap fossil energy, primarily oil. 2. PO hit here in 1970 and imports soared, consumption soared, debt soared. The buy now something-for-nothing Las Vegas mentality took hold, our domestic manufacturing capacity collapsed except for the medical sector and the suburban sh_t box sector. "Rebuilding" our economy the old way will depend on cheap oil and cheap money. What will we rebuild? We have little manufacturing, 18 million vacant houses in the suburbs, horrific debt, destroyed worldwide credibility and a congress that bailed out the companies most directly responsible for this debacle. PO has come and gone and world oil production falls off a cliff within the next 5 years. We can't afford cheap oil now. What happens when it really get's expensive? But these problems aren't the biggest issue. We humanoids rely on our limbic system and not our neocortex to plan and adapt. This has been widely reported as following a "hyperbolic discount function" curve. Excuse me a minute. The captain just came over the ships intercom saying we had hit something. I goota go and look for a life jacket.

Thirty years?

GDP per person Unemployment (2007)

US--$45,725 4.8%

Aus--$36,226 4.9%

Nz--$26,611 3.8%

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richest_country

Hmm..that sounds familiar.

- Yes, that's her.

- Lot of problems?

Multiple traumas, spleen,

liver, lung, flail chest...

...left neck of femur, renal shutdown.

Reads like a grocery list. She salvageable?

(To Johnny the Boy aka kiashu)

The chain in those handcuffs

is high-tensile steel.

It'd take you ten minutes

to hack through it with this.

Now, if you're lucky...

...you could hack through your ankle

in five minutes.

Go.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mad_Max

As most people know, unemployment figures are meaningless since they're counted in ways to minimise them; if a university student works they're counted towards employment figures, if they don't they're not counted towards unemployment figures, if a person works at least one hour in a week for money they're counted as "employed", which in a country with a rather low minimum wage does not exactly indicate great prosperity.

GDP per capita also doesn't mean much. How is it spread out? If I'm receiving a disabled pension of $10,000 and a $100,000 accountant moves in with me, the per capita income of the people in my flat went from $10,000 to $55,000, am I better off? Is the accountant worse off?

In the US in 2001, 10% of the population owned 71% of the wealth, and the top 1% controlled 38%. The bottom 40% owned less than 1% of the nation's wealth. If 40% of your body economic gets only 1% of the blood circulating to it, then your body economic is sick.

By comparison, in Australia in 1999-2000, the richest 20% of households received 48.5% per cent, and the poorest 20% of households 4% of total income. So we have terrible income inequality, but much less so than the US.

How many banks have collapsed in the US? How many of the country's mortgages foreclosed on as a fraction of the whole? What proportion of the population are homeless? What is the rate of murders, assaults, armed robberies and aggravated burglaries? Compare now to Australia or NZ.

It goes beyond per capita GDP. Me and the accountant's incomes do not reflect how happy and healthy we are. It's thinking that the only important thing is total money got the US into its current problems in the first place.

"In the US in 2001, 10% of the population owned 71% of the wealth...in Australia in 1999-2000, the richest 20% of households received 48.5% per cent"

That's comparing wealth distribution to income distribution - it's not apples to apples. How do they compare if you use income for both (income is more important for analyzing economic stability and day to day welfare, I think).

Another interesting fact: the graphs that show the current US housing decline coincide with the peak in CC.The extreme volatility in the world markets only reflect the fact the world is headed to unprecedented economic dislocation.In an economy based upon infinite growth for success - the decline in energy resources is a death knell.I believe our Scandinavian friend Kjell Aleklett predicted this type of volatility in the economy when the peak is being crested.Kudos to him....What is taking place as we write is ostensibly the consolidation of all the assets of the world into the hands of a very select few through fear and the over extension of credit via printing money on a scale unprecedented in contemporary history in an attempt to prevent the inevitable collapse; i.e. national socialism on a scale never seen before.

I fear that the next 'bubble' is going to be the USD itself.

Whether one call it communism, socialism, or capitalism it does not matter - they are merely semantics during this current paradigm.'Communist' China is more capitalist now than 'capitalist' America, which is perhaps the largest socialist economy in the world at this point in time, and it seems this trend in America is increasing with rapidity.

And just think, the vehicle of this socialistic consolidation of wealth is by means of a fiat currency that in reality has always been worthless...amazing what greed can do to some people.I guess the appellative 'masters of the universe' given to the elites of Wall Street is somewhat justified.Maybe we Americans should start calling ourselves 'the cattle of the masters of the universe'....CYA

Good post.

Re: measures of GDP continued to increase leading Alan Greenspan and other 'enlightened' economists to the conclusion that our economies were less dependent on oil than they used to be and thus less vulnerable to another oil shock.

I wonder how much of the GDP growth of the past decade is based on "growth" in the financial sector which now appears to be completely bogus.

It's clear that oil prices have been a trigger of the current crisis, as well as high commodity prices across the board (steel, cement, copper, etc.). Now, oil prices are crashing and may go below $40 for a while, putting at risk capital intensive new supply such as tar sand production and fragile new transportation alternatives (what will happen to the new GM electric car?).

The drama is that the time to develop a sustainable energy infrastructure is now but our capacity to invest will be compromised for a long period of time because of the financial meltdown.

Unfortunately I can't find the exact link right now, but somewhere in his 2005 series on what was driving the GDP, Stuart tried to answer that question and came to the (contentious) conclusion that almost all of the growth in GDP was down to consumer spending and not transactions in the financial world.

However, Steve Keen at debtdeflation.com did calculate that around 16% of recent GDP growth has come from the expansion of credit.

Phil,

Stuart had two articles on 21st Oct,2005 showing that VMT and GDP are constant. However, he also showed that that oil intensity had dropped by 50% from 1970-2003, a 2% annual reduction. Overall OECD countries have had a 1.3% annual reduction in energy intensity over last 50 years. Oil intensity would probably be higher than 2% reduction per year.

The interesting conclusion by Stuart in a linked article was that transport has been the slowest to reduce oil consumption but if we had zero GDP growth( and thus constant VMT) the economy could reduce oil consumption by up to 4% per year if all new vehicles had to meet much higher CAFE standards( equivalent to the Prius).

Its a cop-out to say that GDP increases are not real. Just compare the expansion of new residential housing, the renovation of older inner city housing, compare your life-style with your grandparents or parents. VMT is a lot more than just longer commutes to work.

Other economies have high living standards( high GDP) and much lower energy /and oil intensity than US, in fact most developed countries, with the exception of Australia and Canada that are large resource exporters.

Seems relevant to this topic:

A Desire Named Streetcars: Alan Drake to be Interviewed on “Think” at KERA.org at Noon Central Time (US, on Monday)

No, it's even simpler than the picture you paint, Phil. Oil prices rose steadily in the last 8 years, leading to a steady rise in inflation, and this led directly to interest rate hikes by central banks all over the world, which in turn led directly to the problems with mortgage repayments. A chain as easy as dominoes to follow.

Mamba,

EXCELLENT job in seeing a much more obvious chain of events. There are so many convoluted theories out in the peak oil press now attepting to connect peak oil to the financial crisis it boggles the mind.

If there is any connection (which I think is greatly debatable), it is at the price point, and you have shown the directness of it. I personally think there is virtually no connection between the current economic mess and peak oil, and even folks who try to make such a connection usually say somewhere near the end of a long and complex analysis, "but, even without oil price increases, it was coming undone anyway", thus pretty much undercutting their own complicated analysis.

Remember what a boom the world was on from about 1982 to 1999, with only a very brief "psuedo crash" in 1987...huge long run up=huge and potentially long downturn. Things are going exactly as they should, peak oil or not.

RC

If this is correct then why all the credit ?

Why not allow the economy to grow using real gains in wealth ?

How come we had to resort to a ever growing debt bubble to keep the GDP increasing ?

I disagree with your analysis. Sorry oil and fiat currencies and debt are interwoven.

You can look at it from different points of view but the bottom line is your dealing with a tightly coupled system changing your view points does not alter the reality.

Since oil is finite obviously if we continue to extract it production would increase then decrease over time regardless of the financial systems we use. The depletion of a natural resource does not change just because we deplete it using different monetary systems. In fact if you look Russia and China which where not based on capitalism have very similar production profiles to the US. However a peek under the covers shows mountains of debt and fiat principals at play. Different rules same intrinsic problem.

Its always been a petrodollar problem and will remain a petrodollar problem. Not a oil problem not a fiat dollar problem but both and tightly coupled. The fact that both also obviously have a natural or intrinsic peak and fall independently is irrelevant.

memmel,

Your first question "then why all the credit?" is a very good one, and it has amazed me that almost no businesses now seem to run on profit from ongoing operations! Even local little shops and restaurants seem to run on a constant stream of borrowed money, literally week to week, so when the credit lines dried up, the business fell on it's face. Where was the operating profit? Some of these little shops have been in business long enough they should have been able to buy and pay for the place 10 times over, but they were still running on borrowed money!

The "oil is finite" argument to explain the economic crisis to me is more problematic. Oil has always been finite. Did we suddenly just realize that? I do not disagree with the core concept of peak oil at some time, the problem is not if, but when? It could have happened last week or last year, or it could be happening today. On the other hand, we have to accept that our count could be wrong and it could happen sometime in the next 10, 20, or even 30 years. One day is as good as another, and we have no real way to know what day peak has or will occur. This is what makes peak oil so very dangerous, because all planning has to be done in the dark. But it is also what keeps peak oil from having a direct effect on the economy until well after oil production has dropped year on year for several years in a row, and even then, recession and changes in vehicle efficiency and driving habits along with fuel switching could also disguise peak oil. Peak oil will be almost impossible to prove, even a decade after the event. It can even be hard to define, much less prove!

On a slightly different note, but somewhat related, has anyone noticed that NOBODY seems to be hoarding oil? Instead they are hoarding so called "fiat" money! People who were talking oil hoarding at $147 per barrel now have no interest in hoarding it at the givaway price of $65 per barrel! Likewise propane and natural gas...fascinating.

I was the one who tried to warn people (and was usually very rudely dismissed) of a possible fast drop right here on TOD back when oil was $140 per barrel. I have also said that anything below $85 to $90 was insane, given the demand for oil from Asia and the price inflation of other major living expenses in the economy (at the price of $65 per barrel, oil is not even keeping up with college tuition, medical and insurance expenses, rent and house prices even after the recent home price collapse) Oil at the current price is essentially giving it away for at least a third off compared to real market value and barely above cost to produce for many nations, a cost that has to be rising. RIGHT NOW is the time to be hoarding oil, and especially propane, not when it is $150 per barrel! After we get the speculators and hedge fund idiots somewhat shaken out, I am long on oil at $55 to $65 per barrel, and think propane is a STEAL at these prices. Nat gas is harder to read, but must be nearing the floor price.

RC

Oil has always been finite. That has always been reality. That reality is only now starting to bite as we are approaching or are probably even already past the peek.

So sure, the supply has always been finite. But things change when you reach the point where growing demand "bumps into" the hard physical limits. Before you reach those limits, you have "frictionless growth" once you hit the limits, more and more friction gets added to the system, until the growth has to come to a stop and eventually reverse itself.

Think of it this way. You have a vast amount of stuff in the ground. Some of it is easier to get out, and some of it much harder. Initially, as we only start discovering how great this stuff is, we don't really use much of it. As we discovered how great it is, we continue to use more and more of it every year. Because there is so much of this stuff that is easy to do at first, since what we use is so small in comparison to what is in the ground. And of course we also start by extracting the easy to get to stuff first.

But with steady growth then there comes a point where our consumption is so enormous that the supply cannot keep this pace of growing at the same rate. This starts to put a brake on the system, which was close to "frictionless" before. Then we also start to run out of the easy to get stuff, and we have to go for increasingly harder to get stuff. So more fiction keeps getting added to the system as less of the easy stuff remains.

Eventually there must come a point where shrinking physical limits become the main driving force of the system and rather than an accellarating/growing econony we are transitioning into one that is decellarating/shrinking.

I guess you could argue (as you did) "why now?". Maybe the transition point is far into the future. But I guess most people here don't think so. And with all the stuff going on right now: crazy swings in oil prices, credit meltdown, etc. it sure looks like times are changing.

It looks like we passed peek-oil a while ago and serious economic fall-out from the brakes that are being put on the engine of the economy, because it is literally running out fuel, are starting to really show themselves in a number of different ways.