Oil Demand Destruction & Brittle Systems

Posted by jeffvail on August 20, 2008 - 11:08am

I've seen a number of comments, both at TheOilDrum and elsewhere, suggesting that the US is now less susceptible to supply disruptions because we have reduced our demand for oil by several hundred thousand barrels per day over the past year. In general, I get the sense that people think we can insulate ourselves from supply disruptions, from our dependence on potentially unreliable foreign sources of oil, by improving our efficiency and eliminating "unnecessary" oil consumption. In my opinion, this is backward. In this post, I will argue that, because the demand that is destroyed first in a free market is the demand that is easiest to eliminate, the resulting consumptive system is more inelastic, more brittle, and more susceptible to systemic shock from supply disruption. I will approach this argument by outlining what makes a system either resilient or brittle and why market-driven demand destruction creates a more brittle system. I will conclude with a few thoughts on how we can increase the resiliency of our energy-driven economy in a future environment of declining energy supplies.

Figure 1: A hypothetical model of market-driven demand destruction illustrates the theory that the highest elasticity demand is destroyed first. This results in the remaining demand being, in aggregate, more inelastic. "E" figures are meant only as relative measures of demand elasticity and are not meant as actual values for price elasticity of demand.

What Makes Systems Resilient or Brittle?

A system is brittle if it is unable to effectively absorb shock. Consider a plate glass window in comparison to a trampoline net. The plate glass window can take a significant shock without budging, but at some point it can no longer absorb an impact and fractures. It is brittle. The trampoline net, on the other hand, will be moved by even a minor impact, but because of its ability to deform and stretch, it will not fracture (or tear) until far greater stress is applied then is needed to break the glass window. The trampoline is resilient. These same qualities of "brittle" and "resilient" apply to economies and financial markets.

The Problem with Brittle Systems

When an economic or financial system is brittle, it is less able to absorb the impact of a shock or ongoing stress--say, a geopolitical disruption to oil supplies, or the ongoing, grinding problem of geological peak oil. When a system is resilient it tends to be able to absorb such impacts, giving the underlying system time to reorganize to eliminate or mitigate the stress event. When a system is brittle, however, it is more likely to shatter, after which point it can no longer bounce back to its original shape. When an economic system shatters, we call it "collapse"--the system enters a downward spiral into depression and dissolution. This is one of the "worst case scenarios" for the impact of peak oil--that it will overstress a brittle global economic system and act as the catalyst for economic, even societal collapse.

For this reason, it is important to understand what makes our economic system brittle or resilient, and how our personal economic choices and political/policy choices can influence the character of the system. In this post, I will look specifically at the how crude oil demand destruction changes the systemic elasticity of demand for oil, and how this makes our economic system more brittle.

Why Demand Destruction Makes a System More Brittle

The basic mechanism underlying this theory is that, when forced to eliminate consumption of oil, individuals, and the market in aggregate, will eliminate the most discretionary consumption first. As a result, the remaining consumption will be more valuable to the individual, firm, or economy in terms of GDP or quality of life produced per barrel of oil consumed. This remaining demand is more inelastic. When the oil demand--whether it is for a family, industry, or nation--becomes more inelastic there is greater exposure to supply disruptions.

For example, the US economy that consumed roughly 20 million barrels of oil per day in 2007 was less vulnerable to a theoretical geopolitical disruption removing 5 million barrels of oil per day from the world market (say, war with Iran) than a future US economy that only consumes 10 million barrels per day due to market-driven demand destruction. The reason is that, presumably, that future US economy cut the least valuable, most discretionary 10 million barrels per day of consumption, and the remaining 10 million barrels per day of demand is far more inelastic.

Is Market-Driven Demand Destruction an Example of a Market Failure?

The tendency of a free market to cut the most elastic demand first seems to be an example of market failure--that is, where the market action produces a long-term result that runs counter to the goals of the market mechanism. One of the classic causes of market failure is where the market acts to optimize short-term benefit, but in the process creates significant long-term problems that aren't adequately accounted for due to inability to incorporate these long term costs in the analysis of present decisions.

We saw exactly this in the rush to extend credit to increasingly low income home buyers resulting in today's "credit crunch," and I predict that we are currently seeing a similar market failure in the market's destruction of the most elastic demand first. The result will be an increasing vulnerability to future supply disruptions--unfortunately, this will come exactly as the likelihood of more severe supply disruptions increases, as I discussed in my recent article on Geopolitical Feedback Loops.

Measuring Inelasticity: Is it Purely a Price Issue?

The standard measure of demand elasticity is as a function of price. Unfortunately, this is not necessarily a good measure of the impact on systemic resiliency. Even if prices are going down, demand inelasticity can be increasing if the cause for the price drop is that high prices have caused an economic downturn that is eliminating the most elastic oil demand. There are indications that this is exactly what is happening at present--high prices are creating demand destruction, at least in the US, but the demand that is being eliminated appears to be the most elastic consumption. A better measure of the impact of demand inelasticity on systemic resiliency may be price as a percentage of median disposable income.

Comparing the Credit Default Swap system to Demand Destruction

It is useful to compare the process of increasing inelasticity of demand due to market-driven demand destruction with the systemic brittleness created by the mushrooming market for credit default swaps. I've written a brief explanation of this shadowy corner of the financial world in Financial Wizardry & Collapse. In brief, by spreading the risk of default on corporate bonds very thinly and widely, the global financial system becomes superficially more resilient as it is better able to absorb a handful of major failures. However, because the system is so interconnected, at some tipping point of numerous defaults, the entire system would crash at once. The result is a system that is actually far more brittle.

The credit default swap (CDS) system is in some ways useful in understanding how to reduce the brittleness caused by market-driven oil demand destruction. In the CDS system, individual corporations or issuers essentially bet on the viability of corporate bonds--they have the power to choose their level of exposure. Of course, in seeking to maximize profits, there is a trend to maximizing revenues by maximizing exposure to systemic default. Participants can, however, participate in the system while maintaining a safe, low level of overall exposure--a level where they could absorb the impact of simultaneous default of every position they hold. The lesson, roughly applied to energy demand inelasticity, seems to be to minimize the exposure to supply disruptions of the most inelastic sources of consumption.

For example, if winter heating by heating oil is a very "important" (and thereby inelastic), source of consumption, it would make sense to move that use to a more reliable source of energy (say, passive solar design and added insulation) before converting gas-powered commuter cars to plug-in electric. This also applies to electricity and natural gas use--for example, the electricity used to pump water out of aquifers for a farmhouse is likely a very inelastic source of demand; replacing this source of energy consumption with rainwater harvesting would improve the aggregate elasticity of demand.

This seems to run counter to what the market and non-market incentives (subsidies & R&D funding) are pushing for--one reason why I think this process demonstrates a market failure--and may be a good candidate for a centrally-planned policy push. This is just one example of how the US could actually increase systemic resiliency by substituting renewable, domestic, alternative energy sources and conservation measures for the most inelastic sources of oil demand (the red section of the Figure 1, above), while retaining the more elastic and discretionary sources of oil consumption to buffer supply shocks.

What About Efficiency?

Do improvements in efficiency have the same effect as involuntary, market-driven demand destruction? Maybe. If the pace of efficiency measures decreases the scarcity of oil, then the result will be a less brittle system. However, this tends to act as a negative feedback loop, as the exact stimulus that drives investment in efficiency (high prices & scarcity) will also be eliminated by efficiency gains rapid enough to decrease the overall scarcity of oil.

Conclusion

As a result of recent demand destruction, the US economy is becoming increasingly susceptible to shocks caused by supply disruptions. The global economy appears to be following suit to some degree, though the process of demand destruction in the growing economies of China, India, Russia, and elsewhere in the developing world is currently less clear than the picture in the US. It appears that the process of demand destruction in the US is a classic example of market failure--not that it is a failure to reduce apparently "unnecessary" or frivolous consumption, but rather that by relying on market signals alone we are increasing the inelasticity of remaining demand and setting ourselves up for catastrophic system failure. While anathema to the orthodoxy (though certainly not orthopraxy) of American capitalism, it is time to consider how we must use non-market mechanisms to plan for increasing our systemic resiliency.

While this may be unlikely to happen at a national level, the need to increase resiliency is scale-free: individuals, communities, bioregions, and nations can all benefit by the increase of resiliency at any level. I have previously addressed one way to increase resiliency--by addressing the Problem of Growth that tends to "eat up" systemic resiliency. In this post I also recommended policy programs that would first transition our most inelastic demand to reliable, domestic, and renewable sources of energy.

If there is a "so what?" point to this post, that is it: rather than work to create viable, stable, renewable substitutes to the more elastic components of oil demand, we would be better served by focusing subsidies and research grants on replacing our most inelastic demand first. Implement policy and subsidy as necessary to replace or eliminate the most inelastic sources of demand first--the exact opposite of what the market would do, but the best way to increase systemic resiliency.

Nice work Jeff. The irony of the Washington Consensus trajectory of removing import substitution policies around the world is that US is as or more vulnerable than many countries. We certainly grow alot of food, make good steel, and other high necessity items, but are the required inputs to these themselves mostly imported? At what price of oil are the benefits of comparative advantage completely offset? $200? $300? I wrote here about oil, trade and basic necessity hierarchies.

Recommend evaluating global demand elasticity as a sum of first, second, and third world contributions. These have orders of magnitude different incomes and consequently very different demand elasticities. e.g., nominal incomes of $30,000, $3,000 and $300/year. Oil's 1500% price increase from 1998 to 2008 has the greatest impact on the poorest in the developing world. Use of first world SUV's drop very little compared to fuel use among the 3rd world poor.

Great post Jeff!

I personally think that gasoline demand can be dropped more than heavy fuel oil demand. Simply because diesel and heavy fuel oils are more "necessary". In other words, most of us could walk to the grocery store, but the grocery store needs deliveries from thousands of miles away.

I personally think gasoline will be much more elastic than the other fuels. This is why I believe heavy fuel oils will stay more expensive than gasoline.

Most options on the market (hybrids or soon electric and plug in hybrids) for being green reduce gasoline demand, not heavy fuel oil demand.

Proof of this is the narrowing of the price gap between gasoline and diesel in Europe. Diesel has "always" been substantially cheaper; this summer we have achieved parity, at a time when cars are consuming something like 5% to 10% less fuel than the same month last year. Personal transport is becoming prohibitively expensive; goods transport is still very cheap.

Freight by truck in Europe still seems to be growing apace; ever-greater economic integration and rationalisation, the delocalising of manufacturing to central and eastern Europe...

Growth in freight by truck in Europe might at least partly come from a relocation of manufacturing from Asia to central and eastern Europe. I've read some numbers on that, but can't recall where. It must have been written in German anyway.

Them big rigs are a rolling

diesel fuel is what they need

If you want to keep them rolling

and groceries on the shelves

best you think about tomorrow

and just slow that Hummer down

From "The end of oil is coming, won't you slow that hummer down"

I see it the other way around. The heavy fuel oil demand is more concentrated on industrial uses. Many of the uses have the potential for fuel switching, or for significant fuel savings, by the substitution of human labor. Take the example of your long distance trucking. At highway speeds roughly 65% of drag is allegedly due to aerodynamic drag. This means the fuel demand, per freight mile is a rapidly increasing function of speed. So the trucker can slow down, substituting his time behind the wheel for lower fuel costs. The automobile driver can do likewise, but his fuel cost savings, measured by his expenditure of time is much lower. Exactly the same thing applies to shipping by water, lower speeds mean higher labor costs, but greatly decreased fuel costs. And this is before technological tweaks. In the case of interstate trucking, trucks could be made more aerodynamic, and a switch from single trailers to double trailers would significantly reduce fuel usage per ton mile. I would think that much of the lowest hanging fruit is in the heavy fuel sector, not the gasoline sector. How many hybrid cars would it take to save as much oil, as a single hybrid garbage truck?

EOS,

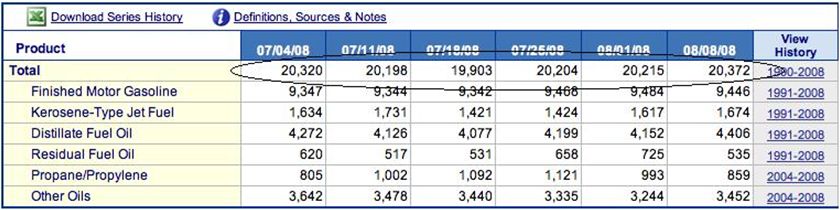

A bit of supporting data for your post.

One of my best friends operates a long haul trucking company. He told me about 6 weeks ago that at 65 average mph his trucks were burning about $12,000 of diesel per month. He decided to limit some to 55 mph and they were burning $10,000 of diesel per month over the same routes. Time to delivery, and other costs, were obviously impacted, but you can see the effect that could be achieved in terms of fuel savings should it be required.

Wyo

I thought a lot about reducing truck energy usage. The basic problem is for any real reduction (greater than 10%) of trucking fuel demand, it would take a long time to happen.

The problem is they have already tried a lot of energy reduction. When a 300 gallon tank costs $1200, they think of what they can to reduce that price. Speaking with truck drivers, they don't have options when it comes to reducing fuel use. The best one is driving slower, which will move some of them from 6.5 mpg to 7 mpg. However, it would reduce the amount of freight a trucker could deliver and thus the profit. It is not a very good option for them. Even if it did happen, it would only drop highway truck consumption by ~5% (going from 75 to 55) and less freight would be delivered.

When it comes to replacing trucks with hybrid versions, there are a few problems. Hybrid trucks are really expensive ( 100k or more than a same model diesel ), don't save much fuel (0% highway, 10-20% city) so they are not cost effective. Also, there really aren't many on the market. Full battery electrics are not feasible with todays technology, not an option.

On the flip side, nearly 50% more of us could take a bus/subway or ride a bike to work 3 out of 5 days a week. 10% more of us could telecommute 3 out of 5 days a week. 75% of the SUV's and trucks on the road could be replaced by economy cars (yes I know, this would take a long time, and is unlikely). We could be moved to the 4 day work week. On top of that, there are many (15+ models from major manufactures) PHEV and EV's coming onto the market within the next 5 years (and yes I drove one, they are good commuters).

Bottom line, within 5 Years, I believe that gasoline demand could drop by 25%, easily. However, diesel demand would be struggling to drop by 10%. There are just way more alternative to gasoline than there are to diesel.

Five percent seems way too low for the speed change. Got any actual data?

This article says going from 65 to 75mpg raised fuel consumption

by 27%!

http://www.greencarcongress.com/2008/05/us-trucking-ind.html

That's probably true in general. Air resistance increases roughly as the square of speed, and so is 33% higher at 75mph than 65mph.

Wyoming, above, suggested a 20% reduction in consumption from the 30% lower wind resistance at 55mph vs. 65mph, which also seems reasonable, as one would expect non-wind factors to be larger at lower speeds.

Either way, though, there are quite substantial fuel savings to be had from reducing speed a modest amount.

Market-driven efficiency can be either more or less brittle than existing systems.

For example:

1) Riding a bicycle or insulating a house makes an individual more resilient in the face of energy price increases or shortages.

2) But turning the thermostat down to 40 F in a poorly insulated house is less resilient because any energy supply interruption will result in pipes freezing and other systemic damage.

Not sure how one could determine what percentage of adaptation is increasing or decreasing resiliency.

Been thinking along those same lines - what adds to resilience and what subtracts from it?

Hi redcoltken

IMO the biggest contributor that adds to it is complexity. Our 'global' civilization is hideously complex and vulnerable to disruption, either of oil supplies or the grid. I've just read Alex Scarrows book 'Last Light' which, although a fictional novel, does bring home just how many days we would be from anarchy if the power went down. Even individual self-sufficiency would be no good if the hungry mob turned up at your allotment. Scary!

tw

I'd add one other point Jeff, on the matter of brittle vs resilient and in particular the difference between 'break' and 'shatter'. How a system breaks is critical to how it can recover and its level of resilience.

Now the electricity system can break quite spectacularly - cascade failures, etc. However its a break rather than a true shatter because bringing it back up again is a well practiced operation that can be achieved relatively quickly, with local resets etc. We can be up and running again fully within a week or two.

However something like the gas supply is a different matter. If gas stops then pilot lights go out, etc. and you can't just restart the system since its a recipe for gas explosions. As Euan has pointed out previously, restarting the gas system from a break is something people don't really know how to do. When it goes its not coming back in the same form, ever. That cascades to those dependent on it, fast and hard.

That's a system that's shattered.

In practice if a failure as cascading effects that feedback to prevent restart and feed forward to have other bigger impacts, its a shatter event and its orders of magnitude more critical than a simple break.

Most civil contingency work doesn't recognise the difference.

I was thinking of "break" and "shatter" on a civilizational level, but I think you raise an important point that applies across scale--the ability to reconstitute (break) vs. irreparability (shatter). Ultimately, it may be an accumulation (or coincidence) of multiple systems shattering that leads to civilizational failure in the energy arena.

While, generally, the electric grid may be easier to restart than the gas grid (and other examples), there are important exceptions to this as well. Hydropower, especially in some regions, represent a critical "black start" capability because they require no (or very little) electricity supplied to them in order to start generating. This is not the case with most other generation options to one degree or another, nuclear being the worst after a prolonged shutdown. Under certain types of grid failure, black start capability is a real problem...

Thanks.

The concept comes out of thoughts on terrorism and black swans, but it applies to the systems of a post peak world - which is something I've been considering.

Of course we could suffer through the slow collapse of those systems we've built up in the peak peak world. However the reality is the transition into the world we here tend to expect is likely to happen through one or more of these shatter events. Sudden catastrophic failure, rather than slow decline - on a civilisation level.

Oil, I feel, is not likely to be at the centre. Rather something that oil maintains that shatters is likely to be highlighted as the cause. Probably electrical power in some form - so much of what we call civilisation has that at its heart.

Any thoughts on what systems can shatter would be welcomed.

Yes, interesting stuff. What about road/rail/air traffic signaling? Could the mass failure of this be catastrophic to our just-in-time delivery systems, or would it be manageable?

I think the theft of electrical cable for sale as scrap seems like one of the scariest tendencies. This is happening increasingly now.

Another worrying thing is that I've heard reports of people following oil/diesel delivery trucks in order to identify where there are storage tanks that are worth stealing from, and are inadequetly protected. Many of the targets are small farms, who then often then need to pay for the clearup costs (where oil has leaked), as well as the repairs to the tanks, and the oil itself.

I'm only familiar with the UK environment by the way.

Garyp:

You said:

Unless you can provide a citation from a utility to support this assertion I would disagree.

Gas equipment with standing pilots is increasingly rare, most now uses electronic ignition. In those with pilots there is a safety on the gas valve of the equipment, If the pilot goes out it cools, and when that happens the gas is shut off, to relight you need to hold a button in by hand to allow gas to flow while relighting the pilot until the safety rewarms, this is a DIY job for most people.

The gas on our street was shut off last year due to a house fire down the block a ways, the Gas Co. just put a flier in our mailbox explaining how to relight, and to call them if we needed help with that.

There might be very old, or broken, equipment still in service with no working safety on the gas valve, in such cases it would take a very long time, probably forever in most houses given that you are likely to get more than 1 air exchange per hour just from drafts even if the windows are closed, for the tiny amount of gas from a pilot to build up to explosive levels (5% of the air volume is the minimum)

Might a house or 2 explode? Highly unlikely, but possible, but this is not a "system that's shattered".

There is an article by Euan on the UK gas supply under TOD:Europe that mentions this issue. Its not just the pilot light issue (of which my mother has one) that contribute to the collapse of the system.

One street is one thing. An entire country is another. If you just reconnect the gas and somewhere blows up, who do you think will be liable? Whatever most may have, it's what some might have that drives the problem.

As for it not being an issue, we regularly have 'gas explosions' most winters as some malfunctioning item causes just this effect and a couple of houses end up a smoking ruin (so much for air exchanges). That's with the status quo.

And if the gas is off for a few days during the winter, as it would be given the various issues, it IS a shatter event, since the feed forward effects are so severe (bring out your dead).

Garyp:

You are moving the goalposts.

Your assertion was, as I read it, that if the gas network goes down it will stay down because we don't know how to restart it, if that is your contention please provide evidence, or clarify what you meant to say.

Yes, malfunctions of equipment, and stupid contractors or owners, sometimes cause explosions (at the rate of 1 in many millions) but this was / is, I would suggest not caused by a systemic supply network failure but by individual equipment failure or human error, and is a "given" regardless of a network failure, its also I think you will find not due to pilot light issues in the vast majority of cases but from things that cause much larger rates of leakage...

Who would be liable? well, who would be liable if the Gas Company failed to restore service to customers who had contracted with them to provide it and preventable property damage or death were to result? Liability exposure cuts both ways. My expectation would be that in such an emergency gov't would backstop the risk. (I'm not American, those folks might be in a bigger difficulty in such a situation I don't know...)

Could a long winter outage cause great losses? Yes, but would that mean that the gas distribution network had been "shattered"? No, the survivors could restart the network, the network being down for some time would not, in and of itself destroy the network (again, if you can point to evidence to the contrary please do so, it's your burden of proof as the one advancing the proposition yes?).

Nice essay Jeff!

One thing your brittle/elastic analogy is missing, it seems to me, is time. As you consider price shocks, each shock (economic stressor) is a discrete event, essentially with time=0. The system must either react elastically, inelastically or with some combination of both; that makes this thought exercise a comparison of the difference between brittle and elastic behavior.

If you insert time into the equation, we get a third type of response: ductile/plastic. Window glass can undergo deformation similar to a trampoline (as long as the force operating on the window glass is modest, steady and of a very long duration), but there is no significant elasticity, because the window will remain deformed once the stress is removed. Perhaps we should attempt to model the ongoing plastic deformation of the economy?

And perhaps I am taking your analogy too far, hence deforming it!

Yes, I like the plastic deformation analogy.

For example, what we see as elasticity in gasoline demand (reduction of relatively discretionary travel etc) might, in theory, rebound like a trampoline (if prices dropped or incomes improved), but it is in fact reshaping the economy and society : giving people strong incentives to move closer to their place of work, to transport hubs, etc, and in a thousand other ways.

Various countries subsidise fossil fuel prices, and are incurring unsustainable costs in doing so. This is (take your pick) foolish, because the market would allocate resources more efficiently, or wise, because it cushions the economic and social systems from the impact that could break them.

I don't think you're deforming it, just adding in realistic complexity that also makes it less clear--funny how the real world works like that! Especially when we start modeling civilization-level resiliency, the system quickly gets so complex that there is little meaningful that we can say about it...

While I agree that as crude oil price increases, and thus product prices increase as well, that the economy becomes more and more strapped, I disagree with your conclusion. However, I disagree with your theory that demand become more inelastic with higher and higher crude oil/product prices.

As gasoline/diesel prices has risen, the use of gasoline has been very inelastic. This is because people can conveniently drive their car to work and offset the higher gasoline prices by spending less in areas which are more discretionary (i.e., change vacation plans, go to movies or go out to eat less often). However, as gasoline prices increase further, they don't have as many opportunities to save as easily to offset the higher fuel costs (for example, they don't want to loose their house), so they have to begin to save by directly lowering their fuel cost bill. They can do this by going to a 4-day work week, commuting by mass transit instead of my car, carpooling... This would result in a more elastic response to fuel price increases than their initial response.

The elasticity of demand data supports my case. Back in the early 80's when fuel costs comprised a larger portion of people's budgets and we then experienced the fuel price shocks, the price elasticity of demand was on the order of 0.2 (many studies supported this). However, more recently (the year 2000 I believe), the price elasticity of demand was estimated to be 0.07. Since the early 80s, fuel costs have comprised a lower and lower portion of their household budgets. As the crude oil price increases, though (above the $150/bbl range), I would expect to see the elasticity of demand increase and demand destruction accelerate, not diminish.

Retsel

The existing elasticity (as demonstrated by your data) is irrelevant--what matters is how demand destruction changes that elasticity. My basic argument holds here--market driven demand destruction destroys the most elastic demand first (as demand is not uniformly elastic). The resulting demand is, by definition, less elastic in aggregate.

Imagine if you have a $1 bill, a $5 bill, a $10 bill, and a $20 bill in your wallet. The average bill value is $9. If you tell your kid they can have any one bill out of the wallet, they'll most likely choose the $20. Now the average value is only 5.33. Demand elasticity works the same way. When faced with high prices, we're more likely to cut Summer road trips than ambulance miles, and the resulting demand is more inelastic.

I agree with your conclusion, that demand destruction makes the system more brittle. However, I don't think the government can respond appropriately. Given time, the market will adapt and become more elastic. Walmart has no interest in having their warehouse-on-wheels vulnerable.

On thing I wanted to point out is I've kept a budget for years, and my gasoline consumption has rarely been more than 1% of my net salary. Gasoline would have to go up pretty significantly before I felt any pinch.

You must either have a much higher income than average, or drive much less than average, or you stopped that calculation back when gasoline was around $1/gallon. For the average American, it's now something like this: 14000 miles at 20 mpg = 700 gallons, at $4/gal that's $2800 - more than 5% of a typical salary.

But "your mileage may vary". E.g., for me it's more like 200 gallons (fewer miles, more economical car). On the other hand, I need to keep a house warm through the Vermont winter...

I agree vtpeaknik,

And a rise in the price of crude oil ripples through the price structure of the entire economy, not just gasoline prices or fuel oil. :(

Given time, the market will adapt and become more elastic.

You are assigning to "the market" a quality that it definitely does not have : intelligence and foresight.

As long as the worst has not happened, "the market" does not know how to price it, and will take no adaptive measures.

But individual actors can. You are right that "Walmart has no interest in having their warehouse-on-wheels vulnerable" : it is precisely such major actors who can take adaptive action. They might evaluate a risk of a catastrophic failure of their business model at some future unknown date, and insure against it by moving to a lower-energy logistical model. But this would be more costly, therefore they will only do it if they are confident in their evaluation of risk.

They could, for example, build warehouses at rail freight locations and re-tool their truck fleet to deliver from these. This would not, in fact, increase elasticity (that would require that they maintain two alternative freight distribution methods, which they wouldn't do) but it would lower diesel demand.

However, Walmart, and other entities of their order of magnitude, are the exception : they carry as much weight as most state governments, and are capable of foresight and wisdom, if they want. The rest of businesses, and the mass of individuals, can't and won't plan for disaster.

Bottom line, Fred : the market will evolve under gradual pressure, but will absolutely not plan for catastrophic failure (and I suspect that the insurance sector is as decadent as the banking sector has proved to be! i.e. incapable of assuming its basic function of risk analysis and hedging).

Ergo, government action (regulation and taxation) is all you've got.

If we get to the point where we are debating whether or not to drive ambulances, then elasticity won't matter, as the world economy will be kaput. We have a long, long way to go in terms of demand destruction before we get to that point.

If the U.S. reduced our oil demand to be the same as Europe's, our gasoline demand would be half that of today's, and yet Europe is fine at its level of fuel use. We have a lot, a very lot, of elasticity to go before we get to that brittle point. In the extreme case, the country will go into a recession or a depression, and the elasticity numbers will be huge (the fuel demand is not so inelastic when we have a recession, as the portion of people out of work don't use much fuel).

I agree that times are different compared to the 1980s. One very important difference between how people will react to higher oil prices today versus 28 years ago is that peak oil is better understood. Many people understand now that they cannot simply go out and replace their SUV with a newer SUV with slightly better fuel economy (a V6 instead of a V8), because oil prices are likely to continue to increase. They, instead, will go out and purchase a compact or a hybrid.

In our case, my wife and I replaced our thirty eight year old 60% efficient natural gas furnace with a 400% efficient ground-sourced heat pump, at the tune of $23,000. If we thought that natural gas prices were only going to increse to $8/mmbtu, we would have put in a 90% natural gas furnace. The payout is poor at $6 or even $8/mmbtu, but at $20/mmbtu we will look like geniuses!

Retsel

But there is no constituency in the US for such action. The market is defined by existing corporate interests which see no need to "make space" for a competitor. This structural inertia is a significant aspect of the problem.

garyp brings up another important point and that is the degree of coupling between elements of the system. If there is a tight couple then a failure at point A will cause subsequent failure at point B and this will cascade through the system resulting in catastrophic failure.

Most engineered systems (my experience is with offshore drilling units - the Military and NASA employ similar methodology) will be designed to "fail safe." This ensures that any single critical component failure cannot propagate through the system. Or the system will have built in redundancies (think RAID or multiple power plants on fixed wing) or will be designed to avoid a tight couple between components (lots of small independent economic units rather than a single integrated global economy with a high degree of interdependency). And if all else fails there will be some form of lifeboat capacity. Hard to supply that for 9 billion souls.

Exactly because there is no constituency in the US for such action is why I think this is a classic market failure. I'm generally hesitant to advocate centrally-planned solutions. I guess I appease my concern for central planning in general by suggesting that we resort to "scale-free central planning." What I mean by that is that it isn't only the Federal government that should look to substitute the most inelastic demand first--individuals, communities, and businesses should do the same, and will likely have more success doing so.

I think your comment on systems engineered to be fail-safe is important. As you point out, the systems most likely to be engineered to a relatively fail-safe standard are those in the military, NASA, high-consequence engineering projects (e.g. dams), etc. Especially where we see our infrastructure privatized, but also where it is the product of constrained government spending (e.g. outside DoD), the result is far from fail-safe as corporations and government agencies are forced to show short-term improvements in services delivered and profits gained. This leads to cutting corners on long-term fail safety measures, etc...

I think you are highlighting the difference between Keynesian and Friedman style capitalism/governing systems. Both believe in free markets and price signals but are polar opposite about how best to use those signals.

Keynes approach forgoes driving for optimum efficiency of the system in the present to maintain a structural integrity (efficiency) of the system itself. Friedman and "pure Capitalists" are all about maximizing efficiency now without regard for future conditions.

As you and others have posted the most efficient (from simplicity and cost) systems will by definition have no redundancy built in. Great if your only worried about profit or an I-pod, not so good if you are at 30,000 feet in a plane or totally reliant on one energy source for your survival. There is more than one kind of efficiency depending on your frame of reference.

Hi Jeff,

I appreciate your choice of topics.

I'm wondering how you see what we might call the "military function" and/or sector. I have the impression (and stopped trying to find links for lack of time - you probably know much more than I on this topic) - the "military-industrial-(insert additional)-complex" is one driven by a kind of corporate interest in looking for new "needs" for new "products" (this would constitute the classic "arms race" argument in brief) - as opposed to functions.

I mean, if this were not the case, we'd have a lot more effort (and energy and money) devoted to things like "Peace brigades international", human rights accompaniment, humans rights orgs, "mediators without borders" and so forth.

Under the guise (or rationale) of a military function being one that fits into the category of "inelastic demand", we actually end up with what actually appears to be the opposite of demand-driven production. (If this makes sense.)

So, that's one question.

Thank you again, Jeff,

"Exactly because there is no constituency in the US for such action is why I think this is a classic market failure."

1) What do you see as the cause of the lack of constituency?

Do you think it's because people are unaware of the infrastructure and energy relationship, say, WRT food or water? (Plus lack information about "peak" and what it means.) And thus, there is no mandate to create something like distributed-energy-supplied or other means of helping promote resilience?

One place where we might find something we could label a "constituency" is WRT food - farmer's markets and the "purchase local" movement. (Not a large constituency, still...something).

2) Even WRT corporations. It seems to me that if we restrict our set to "nationals" as opposed to multi-nationals, then it seems like it would become easier to make the case to shareholders that higher (initial) costs to introduce lower FF usage is a good idea because it prevents collapse down the road. (If it does.)

Anyway, all to say...it seems to me there's a logical way to go, namely, a sector, say, healthcare delivery...starts to think about what kinds of "structural changes" or "structural adjustments" (shorten supply chains, try to set up regional manufacturing of most used supplies, etc.) (just trying to find an example)- make sense in view of declining FF availability.

If it is only a matter of information...? Then, what stands in the way of people having the information they need?

3) "...will likely have more success doing so."

What are the tools and means available to "communities"? Do you mean local governments? How can individuals and communities find capital in order to either make "structural adjustments" or put in place "alternative energy sources", since these require doing something other than continuing with their present growth BAU assumptions?

In other words, how do you figure they would have more success? I like the sentiment, but wonder how it might actually play out. (Also, since my personal efforts in this direction have met what looks to me to be exactly zero success to date.)

One centre of "fail-safe" planning excellence which should be tapped : Data center management.

They are, in general, these days (hedging here!) pretty damn good, and pretty cost-effective because it's a very competitive business (whereas, for example, the nuclear sector is pretty damn good but very expensive, and NASA has been awful because cash-strapped).

So perhaps the govt should hire some high-powered data center systems gurus to do some contingency planning against crash-and-burn of Civilization As We Know It.

Good point about data centres. I make my living writing large business software, and one of the most critical semi-annual events we deal with is the "Disaster Recovery Plan testing" exercises. This year its complicated by the fact that the actual site of the backup equipments physical installation is no longer on any maps, including Google or Mapquest, so participants need to be given hand-drawn maps of the location they need to go to, not just an address out in the country.

Perhaps local governments should start doing "Disaster Recovery Plan Testing" for serious disruptions such as transportation failures, electric and gas grid outages, etc. Would at minimum be a very good way to publicise the reasons and needs for such planning. Local media interest, schools etc.

My homespun way of thinking of demand destruction is that conservation eventually transforms into deprivation and deprivation eventually leads to death.

As far as flexibility of dealing with energy shortages, freedom (of which free markets are a part) gives the greatest number of people a chance of survival. Freedom is the opposite of rigid, bureaucratic, centrally controlled systems. This is why my personal steam safety valve whistles every time I see proposals here and elsewhere for solutions which government must undertake to save us.

If you want to make the system less rigid, get government out of economic planning and control completely, and eliminate all the special privilege laws granted by government to special interests, which privileges just rig the markets in favor of the few at the expense of the many. This will not eliminate the underlying problem of finite resources, but will mitigate the damage as we face a world with progressively less available energy.

Henry,surely by now you should have seen the disasters inherant in laissez faire systems.

When it comes to building a workable,sustainable nation it should not be a choice between "rigid,bureaucratic,centrally controlled" or a free for all.This is what I call the ideological trap.The old USSR fell into the former version and the USA the latter.Blind faith in communism or capitalism is akin to religious faith - irrational.

Markets and industry have to be regulated because,if allowed to operate without a guiding hand,they will self destruct and take the innocent along with them.Human nature is at the bottom of this.There is a happy medium between that and the command economy.

An analogy-A sail boat with vane self steering can be set up to sail without a hand on the tiller.However,once conditions change then the crew must adjust the vane,sails or course.If conditions worsen then the self steering must be disconnected and the boat steered by hand.

The US is a blend of plenty of economic fascism (government control of private property), plenty of socialism (government operated enterprises) mixed with the remains of a once free economy.

Freedom is a value which serves life, in many minds second only to life itself. Your advocacy of government control instead of freedom in economic matters is the path that I am warning against. We suffer daily from the plunder of the majority by the few as a result of government interference in free trade, giving advantage to some and disadvantage to others.

You analogy of a sailing boat is laughable, simply because in a free market there is control. Individuals making decisions about what they want control what is produced by revealing their desires through their spending.

I find it quite strange that anyone would advocate bureaucrat and politicians making the decision about what is best for himself. It never happens the fairy tale book way. What they do is make decisions about what is best for themselves and those who support them. This is the repeated lesson of history.

I have no doubt that as things fall apart that there will be plenty of begging for government to do something, and they will gladly oblige. The collective solutions will be disaster, just as has been mandated ethanol or the government rescue of New Orleans. The collective solutions will crowd out individual solutions because resources are limited, and the overall result will be to maximize the human suffering from the end of the industrial age.

I smell a false dichotomy!

It sounds to me like you are arguing from and an a priori assumption that government action is always negative and that the actions of the(so called) free market is always positive.

Is that actually your position?

It does appear that way, doesn't it?

Flexibility I think is a form of resiliency, and what Henry seems to be advocating is that there is a set of actions (those performed by so-called independent actors) that are always good and a set performed by government that are, if not always bad, at least misguided.

A flexible stance would be to accept something along the lines of what thirra wrote. A rigid (and thus less resilient) stance would be to advocate all-government action or all free-market action. In the former creativity is stifled and in the latter no businessperson will internalize any cost it isn't forced to, which leads to the gross mistreatment of workers, the environment, etc.

Good? What is that?

The principle upon which freedom is based is nonaggression. What is lawful is free association and actions which do not directly harm others. Any private activity is legal as long as one party is not forced against his will to do or not do something not involving aggression. The purpose of government in a free society is to facilitate defense against aggression of foreign governments and to punish acts of aggression domestically by one individual against another. Hence the need for an air force, a navy and a militia. Hence the need for courts and prisons. Any part that can be privately done is better than the lumbering inefficiency of government, hence private police and insurance are preferable to government police and prosecutors, and private arbitration is preferable to government courts, for example.

Government should punish those who pass on costs such as dumping pollution into the commons because this is an act of aggression, but instead government authorized certain levels of pollution and prevents private citizens from seeking damage from those polluting. As far as the mistreatment of workers you mention, this is bogus. The relationship between workers and business is a private matter and either is free to terminate the relationship if it is unsatisfactory. Of course committing acts of aggression by employees or employers is the business of government, say should workers burn the plant or business hire thugs to beat strikers. Setting the terms between employer and employee by government involves force by government, which is aggression by government, a prohibited act. If we created this government, it cannot legitimately do something that we as individuals cannot legally do.

So acts of aggression by individuals are bad and all other acts are legitimate. Some of the legitimate acts are good and some are misguided. All legitimate acts are none of anyone else's business.

Limited acts of government to defend against foreign and domestic aggression are legitimate, and while often inefficient are necessary. We each have a right to defend ourselves, hence we can authorize other groups including government to act on our behalf. Government involvement in economic matters are not legitimate because they involve aggression (force) in free association and contract which force we as individuals would not be permitted to initiate.

I should know better than to get into an argument with a die hard libertarian, but here goes.

This is just silly. Freedom as a concept includes the freedom to be aggressive. All this indicates is that freedom cannot be the sole basis for a society.

That is one of the reasons to have government, another reason is to facilitate trade. Yet another is to provide security to the populace, not just against aggression, but also against mischance and deterioration.

Absurd. The court system works only because it is an independent arbiter that can be called upon by anyone. Any private system of arbitration must be paid for and the one doing the paying will have an advantage in that system.

Without a strong central government there are no commons. Are you implying that it is ok to dump on your own property? If someone buys up all the water rights in Colorado does that give them the right to pollute that water?

The business is free to find a worker more willing to enslave themselves and the worker is free to starve to death. Do these freedoms seem equivalent to you?

This is the second time I've heard this drivel in a week. The entire reason for the existance of a government is to do things that we as individuals cannot do. These things include the ability to coerce the population to move in the same direction. And yes, I said that the government can coerce the citizens.

Goverments are given a monopoly on force within the society because that is required to make them effective. In order for large groups of people to live together there must be a fair arbiter of disputes that can enforce its decrees.

You want to limit the government to dealing with things that you define as aggression. However, your definition of aggression is both inconsistent and arbitrary. If I steal from you that's aggression, if I defraud you is that aggression? If I take advantage of your ignorance is that aggression? Is it legitimate for companies to conspire to blacklist people from employment? Is price fixing aggression? What about price dumping to force out competitors?

Now you can go through that list of questions and say yes or no to each of them, but the issue is that we can all come up with different answers for the list (or in fact, different lists).

--

JimFive

Hi Henry,

re: "economic fascism (government control of private property)"

How about corporate control of private property - and of government, to a large extent?

re: "The collective solutions will be disaster, just as has been mandated ethanol or the government rescue of New Orleans."

Good examples.

Here's my question. How do you find capital for solutions, other than via the government? The current oil infrastructure (including the financial infrastructure, but let's just take something easier for me to talk about, like, say, roads...) was put in place via government's ability to garner capital.

Do you have examples of "solutions" that you see? What are those?

re: "revealing their desires through their spending."

Well, yes and no. It's about impossible, as far as I can tell, to find a pair of running shoes (or most any kind of lower to mid-priced shoe) that is not manufactured in China, for example. So, if one wants to express an opinion ("support regional manufacturing") - it is simply not possible, because the range of items (selection) of purchase is limited.

Or, you can not buy running shoes. So, I don't think it's really possible to argue that spending is the same as exercising exact control or choice. it sounds like a good argument, and it's true in a way, for some things (food example is the best one), where "selection according to desires" exists. However...the opposite cases are also true.

And where, again, is that choice to refrain from high-tech (or even low-tech) export of weaponry? I mean, how, exactly, can one exercise the "choice"? The taxpayer, unwittingly (is my guess) funds this type of corporate "foreign aid". I think this would make the argument that actually supports your "no gov" statement. Which is not exactly the same thing as saying "collective" solutions. (Since we might categorize a collection of individual solutions - eg. garden - as a collective solution.)

Corporations are a good example of government interference in free markets. Government creates these artificial entities. Historically they were created as the recipients of monopoly grant. So had government not interfered in the free market there would be no corporations. Even without corporations, however, individuals would lobby government for special privilege just as many people believe their pet "solution" to the energy problem should receive government largesse; this is however an improper function of government in a free society, i.e., to take wealth from one man and spend it for another. It is immoral; nothing more than theft by a gang instead of theft by an individual. And such a system eliminates competition in the free market and creates competition for government largesse.

The issue you raise about capital only being available from government, I don't understand. Were government and their spawn, corporations, not plundering us to the great extent they do, there would be adequate private capital. To fix this problem you do not plunder more to fund the peak oiler's view of where stolen capital should be directed; you cease the plunder. It would take a lengthy dissertation to address the fraudulent money and banking system that government has imposed upon us in violation of the Constitution, but this is yet another of the interferences of government into the free market that transfers wealth out of the hands of the many into the hands of the few and gives rise to massive economic disequilibrium such as is unfolding in the current financial crisis as it did before in 1929.

As far as solutions, if you mean something that will sustain our current way of living, I think there are none. I am not competent to engineer energy out of thin air, and politicians and bureaucrats are certainly not even close to understanding anything but plunder and control. There may be individuals who might have the genius to timely overturn the laws of physics as they are now understood and keep the shell game going, but I doubt it.

The solutions I see are personal; do what you can to save yourself. Some of us have sufficient capital to relocate and adopt an agrarian lifestyle in a human sized community where the necessities of life are closer at hand. Others might not and may not survive. I think that those who call the loudest for government to save them perhaps do so out of a sense of desperation arising from facing the reality of being unable or unwilling to save themselves. Again I put forth the idea that it is government and friends who have destroyed free markets and the solution is to promptly return to freedom; the solution is not more destruction of freedom by government.

On the issue of production having been shifted away from the US, again a dissertation is required, but essentially after WWII the US imposed the dollar on the rest of the world as the means to buy oil. This created artificial demand for the dollar, artificially raising its value against other currencies. This made foreign goods cheaper and drove manufacturing out of the US. We manufacture dollars and the rest of the world in need of oil manufactures goods to trade for dollars. Honest money, gold and silver were abandoned in violation of the Constitution in order to create this fraudulent money system. The purpose was to allow bankers to create money out of thin air and loan it into existence, both to earn interest on the loans and to give government a ready means to take purchasing power from producers (inflation) when they could not openly tax.

Don't you see the black hand of government every where you look, involving itself in economic matters? Government is force and force is inappropriate except to punish real crime. Instead government has become the criminal and calls for government to solve the energy problem are in reality calls for more crime.

Personally, I see people making choices and electing and supporting politicians who enact those choices. Sometimes we (the people) make poor choices out of ignorance.

The system is far from perfect, on that you'll have my full agreement, but it certainly does look to me like you are attached to your points of view. This strikes me as the opposite of being resilient.

Dogmatism like that is something I hope we can avoid, but am concerned we will not when emotions run high and people react out of fear.

Well people are making choices to elect politicians, but that is entirely different than making choices in a free economy. The system is one of plunder and control by politicians, bureaucrats and privileged interests. By voting for a particular politician what you generally are voting for is who controls the system, essentially a system of fraud, theft, ignorance and economic dislocation and imbalance.

Free people and free economic systems are much more resilient and flexible than one where people vote for rulers who then make choices involving force. No you can't build nuclear power plants; then we must build 100 over the next 20 years. No you can't drill for oil but now you must. Wind power looks like a good idea to T. Boone Pickens so lets take funds out of individual pockets and pony up $1 trillion to subsidize him. Everyone must use ethanol; whoops, forget about eating corn.

My view is that is insanity to look to government to make these decisions. I cannot imagine how anyone can conclude that our economy will be resilient and flexible when it is directed by the inmates in the asylum. Private individuals risking their own capital or the worst of us risking capital they plunder from us seems to be an easy choice.

But again, I think that desperate people who see no future for themselves but likely disaster and a high probability of death, will in fact choose to abandon freedom in return for the illusion of safety. Of course this will just result in being a slave with an illusion. This is not a condemnation of those who seek safety in the collective fold; it is just an observation of how human nature works.

Henry: Your whole thesis depends on the a priori grant of the statement "governments can do no good", which is wrong. Your quaint anarchist ideal of a survival enclave out in the boonies will either be too short of troops to survive when Mad Max comes knocking, or need a government. Going from there to Canadian single-payer universal medicare is simple straightforward logic.

I might also point out that your (and many others) constant argument that currency must all revert to a "gold standard" can be demonstrated completely flawed simply by asking the simple question "Why should the world's currency in circulation be restricted to only that which can be matched by stored accumulations of some yellow metal which is increasingly being more properly used (up and often lost) in industrial processes as a thermal and electrical conductor, and as a catalyst for chemical processes?". Supplies of gold can also be randomly increased by lucky miners. In that case, should its value as a currency standard be proportionately reduced? Ridiculous.

Present monetary systems work fine IF governments can be persuaded to not allow continuous inflation to happen. If voters would simply turf out any government which operated a deficit budget OR allowed net inflation to occur (eg. inflation in any year should be matched by equivalent deflation the following). But voters haven't caught on to that scam yet. Reverting to some silly arbitrary metal currency won't fix that however.

BTW, how many oz. of gold were required to purchase a milk cow 100 years ago? Today?

You disdain for stores of yellow metal as money flies in the face of the history of money and banking.

First of all, most of the gold ever mined is still above ground. Very little of it has been used up for industrial purposes. Additions to the gold supply come from mining which is expensive and requires work. In a free economy with honest money, mining only takes place if there is demand for more money so that mining is profitable. As soon as the demand for money allows the value of gold relative to other things to go below the cost of production, mining ceases. You say that "reverting to some silly arbitrary metal currency" won't fix inflation. If gold were to be used as money, how could it's supply be inflated by any significant amount relative to the existing supply other than by mining? It could not be inflated by other than a very small fraction, and that would be limited by demand for money and the requirement that gold takes work to mine. I am confused that you also argue at the same time that gold is disappearing? So which is it? Is the supply increasing or decreasing? The definition of inflation is increase in the money supply, by the way.

I don't think you understand what money is today. Our money supply is all bank debt except for the small amount of circulating coinage withs is base metal. It is simple to expand bank debt. It requires no work to speak. It comes into existence by bookkeeping entry. The banks create checking accounts out of thin air in exchange for either the government or some private person or business signing a note payable to the bank for an equal amount. This is why in the 1930's the money supply was about 50 billion and today it is more than 25 times that amount. The supply of debt money has grown significantly driving down the value of the debt money so that today it costs dollars to buy what pennies bought before.

So as to your question of cows, in 1909 in Nebraska, a 1000 pound steer brought a farmer $47. Today that same steer would bring a Nebraska farmer $998, or 21+ times more in dollar terms. In 1909 I believe one oz. of gold equaled $20.67 and today it equals $835. In gold terms then, a steer cost 2.27 ounces in 1909 and costs 1.195 ounces today. So today an ounce of gold buys a lot more, but a paper dollar buys a lot, lot less. This is what one would expect because the supply of goods and services has increased faster than the supply of gold. Even thought the supply of goods and services has increased, the supply of debt money has increased even faster.

So you can see that the money we are forced to use by government command "This Note is Legal Tender for All Debts, Public and Private" is in reality a fraud. "Note" means note payable (debt). These notes are "bills of credit". And of course your checking accounts and savings accounts are debts of your bank, payable to you, except the only thing that they are payable in is alternative debt instruments. And you wonder why the banks are near insolvent and the house of cards looks to be about to take a tumble.

So those of you who argue against honest money (gold and silver) I think deserve having your wealth transferred out of your hands through debasement of your preferred fiat. What are you, a masochist?

One final point is that gold is a yellow metal, but its use as money was an invention that made it valuable. It is the characteristics of gold that make it the best money known to mankind (durability, scarcity, high value relative to weight, easy divisibility, difficult to inflate). Every time in history that gold has been abandoned as money, financial disaster has followed. So do you want money you can rely upon (gold) or money that facilitates theft through inflation and promotes wild financial swings and financial instability (debt based fiat)? I think only a fool or the uninformed would reject the former in favor of the latter.

Ask the Spanish, circa 1500.

All currencies are fiat, including gold. The benefit of gold, when it was chosen, is that it:

1. Doesn't corrode.

2. Is dense and therefore doesn't take up a lot of space.

3. Had no value.

Read #3 again. Gold was too soft to be useful for anything. Now we use it as a conductor, but for the most part it is still useless. That is why it makes a good medium of exchange. No one is going to melt it down to make a coffee pot out of it.

The difficulty of procurement of gold tends to encourage a less inflationary economy but it also means that only gold miners can increase wealth. Everyone else is just shuffling money around. In a non-backed economy anyone who can create a product can create wealth by getting the government (or their agents--the banks) to loan them money.

There are several problems inherent in a commodity backed currency, such as the fact that a sufficiently resourceful third party can control the money supply of your country. As well as population increases leading to de facto inflation if demand grows faster than efficiency.

--

JimFive

It is not an argument against gold to point out that once in history there was a windfall of new gold as a result of discovery of the New World. Unless you think we will go to Mars and find gold littering the landscape, I think reason indicates that mining will be the only new supply. Like with oil, gold and silver are limited resources and the easiest to acquire deposits have been found and are being depleted. If a once in history inflation of the gold supply is an argument against gold as money, then what about the constant easy and potentially unlimited inflation of fiat money as an argument against fiat. It is unbelievable that one would chose fiat over gold based on your Spanish argument.

You misunderstand money. If as you claim, gold only has marginal value other than as money, then it is not wealth. Paper money is not wealth either. Any money is just a claim on wealth, the true wealth being the assets we use and consume like houses, machines, oil wells, medical services, etc. Increasing the money supply does not increase wealth, it just diminishes the value of money as compared to wealth.

"In a non-backed economy anyone who can create a product can create wealth by getting the government (or their agents--the banks) to loan them money." ---- It is true that productive effort creates wealth, but getting a loan of newly created money did not produce that wealth, the productive effort did. In either a real money gold system or a fiat money system if capital is not possessed and needs to be borrowed for production, then lenders are available. The difference is that in a real money gold system a loan does not create new money, but in our current debt/fiat system a loan does create new money, thus inflating the money supply and debasing the value of existing money; the former is not destructive or fraudulent issue of counterfeit money, while the latter is. And there is the added benefit that a more or less constant money supply results in lower and lower prices for goods and services as production increases, thus encouraging savings.

I think you need to ponder your final paragraph as it it totally illogical. Even if the impossible happened and someone cornered to gold supply, then such a corner would diminish the supply of circulating gold money, not inflate the supply, and prices of goods and services would go down, not up. As far as population increases or increases or decreases in production efficiency, these are independent of the money system and could not logically be used as an argument for or against a particular system.

No, it's an argument against the idea that gold is inflation proof. Finding a large untapped source of gold will cause inflation.

I agree with everything except the first and last sentence. Increasing the money supply only diminishes the value of money if the productive output of the society has not grown. In an ideal economy the amount of money available would equal the amount of goods and services produced. If production goes up then the amount of money needs to increase so that the new production can be distributed (bought).

Ask yourself how those lenders are going to be compensated for the use of their money in a system where no money can be created to pay them back.

Gold is no more "real money" than paper. It has value because a sufficient group of vendors has declared that they will accept it. It has value by fiat (declaration) just like paper currency. As above, the increase in money supply created by the loan should be offset by the wealth created by the production. It should also be mentioned that the increase in money is not due to using unbacked currency but by fractional reserve banking.

Read it again. There are two separate consequences of a commodity based money presented. The first is the danger that a third party can influence your money supply to your detriment. Another consequence is that an increase population leads to both an increased demand for goods and a decrease in the amount of money available per capita which has the effect of making goods more expensive to the consumer (de facto price inflation). This price increase can only be ameliorated in a commodity based money system if there are sufficient efficiency gains in production to offset them. In a non-backed system altering the supply of money can ameliorate the effect of this price increase.

Prove that assumption, please. Or retract it.

Do you want me to prove that government and privileged corporations plunder us, or do you want me to prove that a free market provides adequate private capital?

I think both are axiomatic. Government came into existence to replace the random plunder that fell upon early agriculturalist who gave up hunting and gathering for a sedentary existence. Deals were made with the more powerful plunderers for protection in return for regular tribute (tax). This was the origin of government as we know it, and is and will always be the nature of government. As for corporations, artificial creations of government, it should be obvious that government created laws give them advantage in economic transactions to the detriment of those not granted advantage.

On the issue of adequate private capital, first look at what the fascists economic system has done. The saving rate in the USA is abysmal. This is because we have a fiat money system that encourages debt and discourages saving. Couple that with huge tax rates and the shifting of wealth out of hands of the many into the hands of the few, and the result is inadequate savings, hence inadequate capital. To obtain funds for investment projects new money is created out of thin air plus the interest rate is managed by the government. When new money is created the value of old money is debased, hence money for capital goods is stolen from existing holders of money.

In a free market with honest money (gold and silver) and without interference in interest rates by government, the interest rate fluctuates to provide adequate capital. Whenever there is insufficient capital to fund projects, the interest rate increases to encourage savings and discourage marginal projects. A balance is maintained based on demand and supply.

In other words, you cannot prove that there would be adequate capital. It simply becomes an assumption by which you wave away any counter argument because the counter argument defies your basic assumption.

You have just demonstrated that you are arguing from religious faith, not from a position of rationality or science.

GreyZone,

I don't quite get your argument.

I think I have adequately shown that there is a balance between private capital and the need for investment, interrupted by our (your) masters manipulation. Do you not understand the system of exploitation and slavery of which you are pawn?

I am not religious, so I doubt that I am making some sort of religious leap of faith. Thank you anyway for the illogical conclusion and condemnation as me as a religious "believer". I suggest that alternatively that you somehow are part of the "mama, come wipe me" group wanting to be taken care of, but not understanding the reality of adult responsibility for one's self and the inevitability of depleted resources. You can want and wait all you want, but the people you see as leading you to salvation are in fact taking advantage of you, and the result is you are swimming in ice water while they are rowing the Titanic lifeboats.

I really do get hacked off by those in society, apparently such as yourself, who are manipulated by those in power and who effectively buy into the slave system. I keep thinking that people should be rational and understand what is happening to them, but the response I get is that they depend upon their masters to protect them. So rely on and on, and I will take care of myself, and we shall see who navigates the Darwinian ocean.

Oh, you don't know me at all, Henry. You simply made an unprovable assertion, I caught you in it, and now you are throwing ad hominems around trying to hide the fact that you can NEVER prove your assumption. Ergo, your conclusion is bullcrap.

I don't buy into the slave system at all, Henry. Those around here who know me know this. In fact, I think your entire civilization is trying to commit suicide, precisely because it is built on untenable assumptions such as yours. At the very worst, we will be rid of people like you who are nothing but shills for the failed existing political system.

Finally, Henry, I am not the one waiting on anyone to do anything. I've been one of those telling people to get out of the existing system for a long time. Nate Hagens knows where I am coming from and why. You are arguing in circles about abstract human concepts that are based upon 17th century ideas intended to keep the wealthy as wealthy as possible and fool the rest of everyone into accepting the status quo. I am arguing from positions based on biology, anthropology, geology, physics, and ecology.

P.S. You have PROVEN nothing and demonstrated nothing. You are arguing a tautology. All you have done is made assertions unsubstantiated by facts. All I did was ask you to prove one of your key assertions. You have failed.

I read this at http://theautomaticearth.blogspot.com/ a while ago. Seems topical.

Ilargi: Talking about free markets: I have said many times before that if you leave the provision of basic human needs in the hands of companies set up for profit, you inevitably end up in a situation where human lives are discounted and people become dispensable.

We see this these days in other parts of the world when it comes to the basic need 'food', for which the world’s poor are prized out of the market. In the US, the reality of the food situation can still be disguised through cheap fat burgers and pop, though that’s only a thin veil, about to be lifted.

Off topic, but New Balance makes shoes in the US. You have to look at the shoe itself to determine where it was made. I can't wear their running shoes but I wear them for walking around shoes.

--

JimFive

Completely false, Henry.

"Free market" systems excel at precisely one thing - maximizing profit. Maximizing profit is often desirable but not always. But as has been demonstrated with the deregulation of northeastern US electric markets, the "free market" has reduced resiliency and redundancy.

So you have to talk about goals. What are our goals? Well, very much of the time, we want to maximize profit, so the "free market" should be used in such cases. But what about when we have other goals, such as wanting a reliable electric grid (not the most profitable electric grid)? In those cases, we have to adopt different rules and different structures. The regulated utility is an example of such a structure with non-free market rules driven by goals other than maximizing profit.

You have to start by defining goals. If maximizing profit is your primary goal, then capitalism gives the appropriate answer. But if you have other goals, then capitalism is not necessarily the right answer. This, in turn, leads to hybrid real economies as opposed to ivory tower theoretical economies which don't work.

"As a result of recent demand destruction, the US economy is becoming increasingly susceptible to shocks caused by supply disruptions"