Angola : A not so short history

Posted by Luis de Sousa on June 30, 2008 - 2:16pm in The Oil Drum: Europe

Foreword

Angola is being awarded with the first number of WOE. I intend to start each number with a short history of the country assessed, in order to build some perspective of its present day socio-economic environment. As I started writing this introductory words it became clear that Angola's History wouldn't be that short.

When I was a child the war in Angola was the finished example of a cold war conflict that entered my house through the TV. It certainly helped shaping the way I see the world and I still can't watch the country without some emotions from that time.

The following text contains some information found on the internet mingled with some of my memoires from high school text books and the many reports I followed throughout the years on the radio and TV.

| ____________________________ |

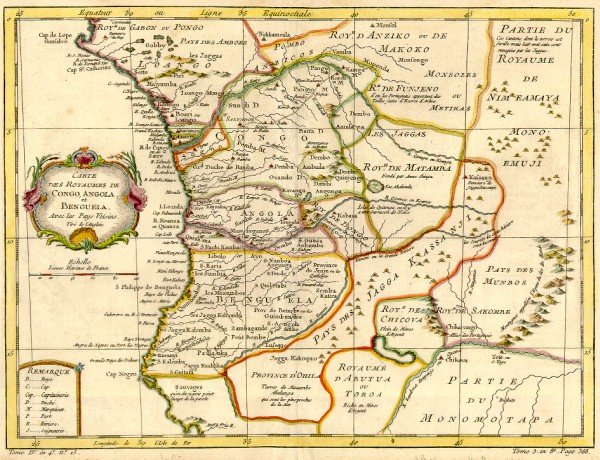

The presence of man in what is now Angola goes back to at least the Palaeolithic, from which time archaeological evidence has remained. Migrations from the north brought iron working to the region around the Congo River by 500 A.D.

In 1482 King John II of Portugal sent an expedition to cartograph the western coast of Africa beyond the Equator. Lead by Diogo Cão, the expedition reached the Congo River in the summer of that year and proceeded south to what is now Angola.

At the time the region was dominated by the Kingdom of Congo that went from what is now southern Gabon to northern Angola, encompassing what are today the countries of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Cabinda enclave. Early in the XVI century the Manikongo (the king of Congo) converted to Catholicism and become a vassal of the King of Portugal. The Portuguese started settling trade posts in the southern shores of the kingdom, eventually founding the city that is now Angola's capital, Luanda.

Unlike other trading regions in Africa where gold and silver were the most sought goods by the Portuguese, in the Kingdom of Congo slavery soon became the main trading activity, thus erecting the Sugar Triangle.

During the early decades of the XVII century, with Portugal and Spain under the same ruler, the Dutch managed to take over much of the region, deviating the slave trade from Brasil. With the return to independence and with the help of Brasilian settlers, Portugal regained control of Congo's shores by the mid of the century. Up to the end of the XIX century the Europeans would stay confined to littoral areas.

By the late XIX century the European powers started disputing control over the vast unexplored territories of Africa, which triggered a new exploration effort, this time directed to the interior of the region. Portugal pretended to claim a vast territory that connected Angola to Mozambique, but at the Berlin conference in 1885 that objective was not achieved. The present borders of Angola were set then, with Portugal loosing access to the northern margin of the Congo river (hence Cabinda's separation from the rest of the territory).

True development of the region only took place after the fall of the Portuguese monarchy in 1910, that gave place to a Republic. Schools were built in the interior and an Agricultural development programme was put in place. Sugar cane, coffee, maize and sisal where the main cultures developed and exported. During the II World War sisal became especially important, supplying a resource thirst Europe. After the war high coffee prices fostered in its turn the region's economic activity.

With the end of the war the main European countries abandoned the colonial rule, but the Fascist regime ruling in Portugal refused to do so. Officially there was no segregation and indigenous folk weren't badly treated, but a huge gap was arising between blacks and whites. Blacks had to pay a fee to attend school, that was out of reach for most working class families. In the improbable case of a black child entering school and later reaching an administrative job, the salary paid would be a third or a fourth of that paid to a white. Society became divided between a white elite that ran services and public administration and a black working class. During the 1950s politic movements for independence started organizing; in 1961 the first armed actions took place.

While the war for independence strived so did oil production. Oil was struck onshore in the littoral of Cabinda during the 1950s, with production offshore starting during the next decade. This oil cycle, that has already entered its terminal decline, would be the main fuel of conflict in Angola.

|

| Jonas Savimbi |

In 1974, in large measure due to the tiring war in the colonies, a military coup d'état took place in Portugal, deposing the Fascist regime and re-instating a plural democratic Republic. Peace treatments were struck with all fighting parties in Angola and a swift transition process to independence was put in practice. At this time three organizations, broadly based on different ethnic groups, where fighting for independence, FNLA (supported by the USA), UNITA (also pro-NATO) and MPLA (a marxist party supported by the USSR that was the first pro-independence organization in Angola).

Angola became an independent country in 1975, just to dive into a civil war between pro-NATO and pro-USSR forces. It was a typical cold-war conflict, UNITA (that soon after merged with FNLA) controlled the city of Huambo and the south of the country, trading diamonds for weapons; MPLA controlled Luanda, the north of the country and oil production. Cuba sent the first troops to support MPLA still in 1975 and South Africa would undertake almost regular invasions of the country in support of UNITA.

The country merged into chaos, with many people simply fleeing; between 1975 and 1977 800 000 refuges arrived in Portugal, most of them from the former elite, many possessing simply the clothes they wore at the time. Although white, most of them had no connection to Portugal, being descendent of several generations of settlers.

With the collapse of the USSR and the demise of the cold war the country entered a phase of negotiations that ended in an peace agreement in 1991. MPLA legalized politic parties and elections were set for the next year. Both parties laid down their weapons and embarked on a heated campaign. MPLA would gain the majority of seats at Parliament, but their leader, José Eduardo dos Santos, failed to secure the presidential race. A final vote was set between him and UNITA's leader Jonas Savimbi, that would never take place.

|

| José Eduardo dos Santos |

UNITA didn't recognized immediately the electoral results and events precipitated into a blood shed. The political arm of UNITA, now seeded at Luanda, was beheaded, with the reminder separating itself from the armed outfit, still headed by Savimbi. The country divided into the worst period of war in its history, where the highest number of victims was claimed. MPLA would advance into the interior of country and capture Huambu, leaving UNITA squandered against the boarders of the country and without any support from the outside world, which by now was recognizing Eduardo dos Santos as the de facto ruler.

A new peace agreement was struck in 1994, that endured up to 1998 when the conflict resumed. The final chapter of the war would be written in 2002 when Savimbi was ambushed and killed in action. Angola had been at war for fourty years.

Immediately after, the deep water prospects found earlier by Petrobras started to be developed prompting the country to an unprecedented period of economic growth. After 16 years, elections will be held again in Angola next September, finalizing the transition from an agonizing war to a stable Democracy, that ironically started with the death of its major responsible.

Luanda today

Oil is bringing wealth to Angola, with many international companies settling in Luanda. This has led to the tightening of economic ties with Europe, attracting many foreign workers looking for higher salaries. The stories they bring back in many ways portrait what the country is today.

Corruption is rampant, encompassing all sectors of the administration, down to police and customs officers. Armed robbery is also becoming an immense problem, making it difficult for foreigners to walk on the street without body guards.

Housing prices are incredibly high, making Luanda one of the most expensive cities in the world; renting a flat can cost easily north of 1000$ per month. Utilities work poorly, 3 to 4 hour black outs are common and water supply is erratic, forcing many homes and buildings to install water tanks.

Most streets are car jammed throughout the day, making progress as slow as 1 km/h. Erratic fuel supplies to filling stations exacerbate the problem. Since walking on the streets is dangerous, foreign workers have to use a car, which leads most of them to take extended work hours, arriving early and leaving late to avoid traffic.

Construction is booming, with literally dozens, if not hundreds, of buildings being built. This infrastructure promises to alleviate Luanda from the slums where most of its population lives, hopefully improving the general quality of life.

The city of Luanda. Click for more.

Luís de Sousa

The Oil Drum : Europe

Luis - Luanda looks a beautiful city - but I'm sure things are a little different on the ground.

We can but hope, but realistically given this country's and this continent's historic record the prospects cannot be that good. Its hard to find countries where oil wealth has translated to real wealth - Canada, Norway, Kuwait and UAE? And they're all characterised by low population.

Who knows? Angola is a special case, the population is not that big, and shouldn't get imense like in Nigeria. Resources are plentifull as so is arable land, Oil could just be the kick starter.

They need to build some sort of welfare state, that's the hardest part.