Fire and Rain: The Consequences of Changing Climate on Rainfall, Wildfire and Agriculture

Posted by nate hagens on February 21, 2008 - 11:00am

The following is a guest post by TOD reader Doug Fir. 'Doug' graduated in the 70's with a BS and a MS in Fisheries, Forestry, and Agriculture. Presently, he and his family work a small hay, timber and livestock operation. The policies impacting climate change legislation are linked in complicated ways to energy depletion. If anthropogenic induced climate change ends up being real and urgent, it will have direct impacts on energy and food production. For these reasons we periodically post thoughtful analysis on the topic of climate change here on theoildrum.com.

The consequences of climate change are often presented in the media as coastal flooding after the melt of Greenland or Antarctic ice. That is the headline most often seen, however the real problems will be much more extensive. I'd like to look at some of those problems, in particular those of wildfire and agriculture, and provide a little background to better illustrate their severity.

Wildfire

One of the more dramatic effects will be the increase in the number, size and severity of wildland fires, of which we recently had a taste in California. "I think we can demonstrate higher severity, larger fires and certainly over the last seven to eight years, more frequent fires and a longer fire season," noted Abigail Kimbell, chief of the U.S. Forest Service. Fire is a natural process, releasing carbon compounds and bound nutrients, usually contributing to the health of an ecosystem in the less intense fires. Ponderosa pine, a major species in much of the west, is classed as fire tolerant, needing light fire to open the seed cones. However, climate change, compounded by years of fire suppression leaving elevated fuel loads, has set the stage for megafires. Steven Pyne, in his book Worldfire, notes four items in his prescription for large fires-abundant fuel and ignition, drought, and wind. Climate change, by changing precipitation pattern intensity and temporal distributions, will provide these.

Looking back at the worst wildland fires of the US, drought created the overall fire danger, the fuel situation and wind determined their size and severity. The Wisconsin Pestigo fire, October 8,1871, burned 1.2 million acres and killed over 1200 people, including the over 400 buried in a mass grave from the town of Pestigo. It was one of 3 major fires that day in the the Lake States, including the Great Chicago Fire and the Port Huron fire, the latter killing over 200. In common, the wildland fires had abundant fuel from leftover slash in the logging and agricultural activities of the North Woods.

The largest fire within the United States broke out in 1910. Known as the 1910 Burn, it consumed over 3 million acres in Idaho and Montana. Straddling the northern Rocky Mountains, it raced from near Washington, over the Bitterroot Mountains and down through Montana, killing 86 people. Nearly 100 years later, vast areas of this fire are still nearly bare of regrowth. Intense fires such as this, as opposed to less fuel-heavy natural fire, degrade the soil. The hot burns can cause extreme depletion of nutrients and organic material, leaving a nutrient poor soil that retards forest regeneration and is very susceptible to further loss via erosion. In 1910, the prescription of abundant fuel had been met in the prior years of discarded logging slash, and was ignited in a droughty, dry summer. Similar fires raced through eastern Washington and north Idaho a decade later, again spurred by abundant logging slash. A collection of stories from the 1910 Burn are here.

We often fixate on what started the fire. In the examples above, debate continues over a meteor shower in 1871, railroads spewing sparks, campfires left unattended; even milking a cow has created controversy. I've fought range fires caused by railroads, campfires, accidental fires, or not so accidental ones. It can be in the early spring, or seemingly wet summer before haying, or in the fall when conditions are ripe. Give it a little wind, and it will jump roads and rivers. Studies from Yellowstone National Park show that while man-made fires account for an average of 6-10 fires, lightning will have caused 35 a year. It doesn't matter the cause, fires have always cropped up.

Climate Change Consequences

Current climate change predictions for much of the West show increased precipitation in the winter or spring, along with earlier and drier summers. The IPCC and Hadley Centre's climate model predict warmer temperatures and their trends indicate increased winter precipitation for the western states. See figures below. The Climate Impact Group of the Pacific Northwest predict "Temperature increases occur across all seasons with the largest increases in summer. Most of the models analyzed by CIG project decreases in summer precipitation and increases in winter precipitation with little change in the annual mean." Long term, 2100, vegetation models show varying woody potential of the west but all cite the greatly elevated fire risks as the vegetation responds to the changing climate. The Climate Change Center of California predicts that "Although climate model results are inconclusive as to whether California's precipitation will change over the next century, all climate models show increases in temperature."

It is difficult to predict site specifics for the region, as so much is also determined by a particular site's elevation and aspect. Should these predictions come to pass, it is a perfect recipe for wildland fires. The west in general already has this overall precipitation distribution, and the vegetation has been selected to survive this moisture regime of little rainfall until autumn. Growth is concentrated in the spring, by summer, tree survival is predicated in large part by tapping deep soil moisture. Longer and more intense summertime droughts will overcome this ability, killing the trees outright or initiating disease mortality. Little snowpack for insulation in the late fall coinciding with a cold snap is very stressful for many trees and has been implicated in climate change mortality for western larch, itself a species with a relatively wide climatic amplitude and hence believed more resistant to change.

The wetter spring will encourage excessive grass and forb growth, only to quickly turn to tinder in the upcoming summer. With an arid climate, these fuels accumulate, and are of the most dangerous variety. Fire managers today prescribe piling and burning slash during the winter after a timber sale. Their primary concern is with material under 3 inches thick, just the size range likely to accumulate with wetter springs. The accumulation of the smaller fuels was part of the case in California fires this past autumn. Additionally here, a more intense fire quickly develops in part due to the density and higher oil content of much of the vegetation. The exotics cheatgrass and red brome, invading much of the west, have already been linked to faster fire cycles, and are cited as instrumental in elimination (by fire) of sage-bunchgrass communities. Although not specifically cited, I wonder about the role of knapweed, a very high oil content exotic which also is infesting the west.

Climate change, by altering precipitation patterns, changes the species composition in the forest. In interior western coniferous forests, the more water-loving firs are replaced by pines or Douglas fir during summertime heat and drought. As drought intolerant species are replaced, they are left to dry, providing fuel and awaiting the next conflagration. Disease outbreaks, as presently occurring with the pine beetle in the northern forests, leave wide swaths of fuel. Forest pathogens are showing a broader ability to infect multiple hosts when the trees are stressed. This is being seen in the west not only with the mountain pine beetle, but also with the spruce budworm shifting to Douglas fir and even hemlock, and with other pathogens. It won't be a peaceful succession to the next vegetation type. Fire will intervene to guide the process, and it will have abundant fuel.

Disease

outbreak in western montane forest

Disease outbreaks present a two sided coin, a distinction noted by researchers at the Fire Science Laboratory in Missoula, Montana. Initially, in their weakened, often dessicated disease state and shortly thereafter, these stands pose the greatest risk for major, swift crown fires. As the needles and smaller limbs drop from the tree, the danger for rapid crown fire lessens, but this fuel is not removed. It is added to the ground, where it's potential for soil debilitating fire magnifies.

A Washington Post series in response to the recent California outbreak highlights a new facet of fire problems. Exurban development is a scene that "bloats with inflammable structures amid an overgrown biota.", according to Pyne. He states that in the new age, fires "rush out of the reserves and into the exurbs." The firefighting response changes, from fighting the fire's advance to saving lives and structures. With climate change, as the author Fitch notes, the problems will only intensify. The solutions offered appear dubious to me. Prescription burning will not fly within such a concentration of wealth. Moving out of the environment is suggested, but even the fire researchers are shown to to have a predilection for the exurban environment.

The problem is not confined to the west, and as the eastern droughts continue, these concerns will ignite there. Ron Neilson, a bioclimatologist at Oregon State and a member of the IPCC, states "The Southeastern United States appears to be among the most sensitive regions in the world to increasing temperatures. It could convert from forest to savanna or grassland through drought, insect infestation, and massive fire." The east, with its higher rainfall and humidity levels, has relied in the past more on microbial decomposition to recycle excess vegetation. Drought and fire will help that change.

The fire situation is summed up by Thomas Swetnam, director of the Tree Ring Research Laboratory at the University of Arizona. "I see this as one of the first big indicators of climate change impacts in the continental United States. We're showing warming and earlier springs tying in with large forest fire frequencies. Lots of people think climate change and the ecological responses are 50 to 100 years away. But it's not 50 to 100 years away--it's happening now in forest ecosystems through fire."

Agriculture

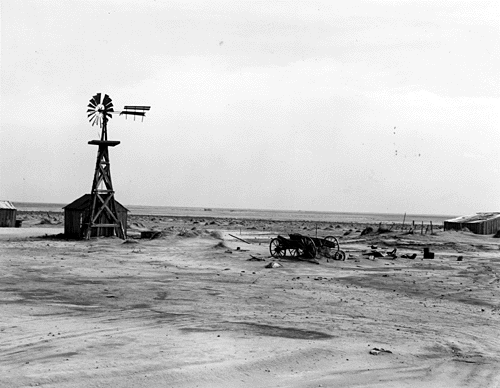

Climate change induced shifts in precipitation will have their greatest effects in agriculture and our food supply. It is difficult to underestimate just how tied agriculture is to moisture regimes. We ignored this earlier in our original cultivation of the plains in comparably wet years, which led to subsequent disaster. We also find it today in reliance on depleting aquifers for irrigation or shifting production. We are teetering on the edge of food supply, and the solutions are not near as easy as the response rolls off your tongue.

Worldwide, people obtain around 70% of their daily calories from grains, specifically corn, wheat, rice, millet, and sorghum. We are down to the the lowest grain stockpiles, around 57 days of consumption, according to Lester Brown of WorldWatch Institute. Any rainfall changes can quickly eliminate the surplus. Skeptics may cite increased yields from elevated CO2 levels, but no amount of additional production from higher CO2 can compensate for drought. In addition, corn is what is termed a C-4 plant, and is less responsive to increased CO2. Preliminary research by Gill, Evans and others also indicate an upper, rather close limit to increased photosynthetic ability. They stress the flora has evolved at an average 220 ppm CO2 over the last 10,000 years and that as CO2 concentrations increase, "we see lots of changes in the way plants photosynthesize, the rate at which they lose water, how they use the nitrogen, and the microbial community in the soil." In part, the limit involves, at least in range and pasture, what is termed progressive nitrogen limitation, as the increased uptake ties up available nitrogen. As this proceeds, there can be a shift from microbial to fungal decomposition. The limitation presents many new problems for livestock grazing and carbon sequestration through biomass, although probably not important to fertilized agriculture.

A quick look at North America. Dryland agriculture is demarcated around 30 inches of yearly precipitation. Higher amounts allow the cultivation of corn and soybeans, less than this and yields drop precipitously. This relation between rainfall and yield should be underscored. From Iowa eastward we reap the bounty, farther west means either a shift to wheat or supplemental irrigation. Wheat dominates as you continue west, but the rainfall and yield decrease. Finally, there is strip farming, where it takes 2 years to grow a crop. Alternate strips, often a mile in length, are planted one year, while the adjoining strip is left fallow to accumulate moisture. This practice starts at about 15 inches precipitation, below around 10 inches and farming is not worth it. Rangeland, already interspersed, begins in earnest.

Montana

strip farming. Half of the land is left unplanted to accumulate

moisture for the following year.

Present mitigation efforts center around earlier planting to take advantage of increased temps and hopefully avoid withering midsummer extremes, crop species changes, shift of crops to more northern areas and finally additional irrigation. These mostly address the increased temperature aspect of climate change, not so much the drought or moisture deficits in major grain growing areas. Development of drought tolerant varieties is in its infancy. With only 5 grains supplying the bulk of our calories, the consequences of this agricultural loss are major..

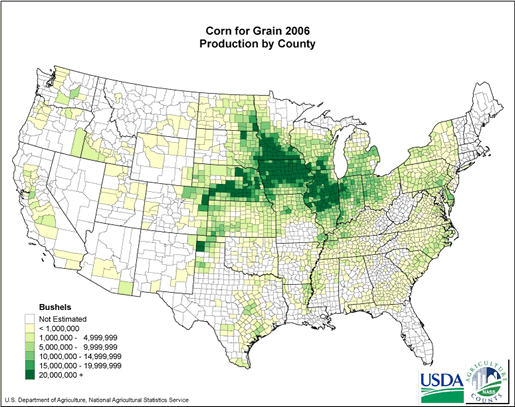

The image of corn yields below highlights the problem of shifting grain production. Western counties, essentially along the state lines from Minnesota/North Dakota south to the Gulf, range from partial to complete irrigation. In the cornbelt of the midwest, high yields and total production are due to rain, but also to the amazing fertility of the soil. Irrigated production in the west such as along the Yellowstone River in Montana or the Snake in Idaho is evident, but these yields are well below those of Iowa. As we move production, we are unlikely to encounter such productive soils. The soils of the north are podzols, derived under coniferous forest and not near as bountiful.

With irrigation left to keep up our production, it seems analogous to oil if you will. Farming enters a sort of enhanced recovery, because we are unable to find significant additional arable land. Worldwide arable land per capita has decreased from 0.38 hectares per person to 0.28 hectares from 1970 to 1990, according to FAOSTAT, 1999. This difference has been made up primarily by irrigation. The irrigable land per capita has remained stable around 0.045, again according to FAOSTAT, 1999. We have been feeding the population increase in part by expanding irrigation acreage and to some extent increasing water use efficiency. Worldwide, we find 15% of farm land is irrigated.

There is a world of difference between irrigation practices in Asia and much of the rest of the world, and how the water is allocated. Asia accounts for 2/3 of the world's irrigated land. Nearly 70% of the grain in China, and almost 50% of India's grain come from irrigated land. In Asia there is mainly paddy irrigation of rice from surface water. To some extent, China and India have incorporated raised beds for corn and wheat within the paddy. However, the main crop remains rice in a traditional paddy system. While new varieties of rice from the Green Revolution have helped to triple yields, in both this and many other crop variety improvements, it often comes at the expense of root development. This makes the plant more susceptible to moisture stress. Reduced yields are becoming more common in dry season paddies due to insufficient irrigation water. These irrigation water supplies are dependent on rainfall to replenish either lowland streams and reservoirs, or mountain snow pack.

Most importantly, agriculture in the US is largely dryland, with irrigated land representing only a little over 15% of farmed land acreage. As might be expected due to its cost, it is concentrated in high value crops. The fact that irrigation represents represents a little less than 50% of the total US farm value is misleading, for the statistic is derived from the dollar value, not food or caloric value.

Percentage of United States Cropland Acreage Under Irrigation, 2002*

| Rice | 100 |

| Orchard | 82 |

| Potato | 82 |

| Vegetables | 69 |

| Dry Beans | 34 |

| Alfalfa | 30 |

| All Hay and Silage** | 16 |

| Sorghum | 10 |

| Corn for grain | 16.6 |

| Soybeans | 7 |

| Wheat | 6 |

| Oats | 5 |

*Computed values from USDA 2002 Census of Agriculture, Farm and Ranch Irrigation Survey

**Includes alfalfa, chop, silage, tame and wild hay.

Excluding rice, in itself a small US crop, grains are largely not irrigated in the US. Our farm grain productivity relies on rainfall, in spite of the extensive irrigation infrastructure. This is not likely to change with present water conditions. Although the thrust of irrigation technology and research is for increased efficiency, I doubt it can compensate for regional droughts. In addition, there are louder and louder voices clamoring for a piece of irrigation water, the largest recipient of water in the US and worldwide. Irrigation practices also have many other drawbacks, including climate change concerns heightened from rice production and the salinization of cropland. Irrigation appears woefully inadequate to address the agricultural concerns of climate change.

Excellent overview of global warming related drought issues in the U.S. Note that other countries are also exhibiting the same problems, such as Australia, and Russia, to name a couple.

General:

- http://ag.arizona.edu/OALS/ALN/aln55/ednote55.html

Russia:

- http://research.uwb.edu/jaffegroup/publications/Siberia.pdf

- http://fire.cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/research/climate_change/activites/firebear_e...

- http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2005/may/31/environment.russia

Australia:

- http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G1-89023209.html

Last year, 60 Minutes did a good story on mega-fires in the western US:

There's some amazing footage of forests turning into deserts: blackened tree trunks rising from the new desert floor.

Very bad news.

Anyone remember the mega fires in the amazon rainforest last year?

"South America chokes as Amazon burns"

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/south-america-chokes-as...

"Roberto Smeraldi, head of Friends of the Earth Brazil, said the situation was out of control: "We have a strong concentration of fires, corresponding to more than 10,000 points of fire across a large area of about two million sq km in the southern Brazilian Amazon and Bolivia."

Thanks for your support.

http://reddit.com/info/69if5/comments/ (env)

http://digg.com/environment/The_Effects_of_Climate_Change_on_Rainfall_Wi...

http://reddit.com/info/69ih2/comments/ (business)

Nice article, thanks Doug Fir.

Climate change effect on agriculture is the most under-appreciated, significant and potentially catastrophic aspect of AGW we're facing. Our food system is dependent upon and adapted to specific climatic parameters. When everyday weather steps out of those bounds, yields will plunge, it will take years to adapt, and never again will we produce the same foods in such quantity.

Backyard gardens and highly diversified operations will have some immunity, but not the big industrial ag. producers. A false Spring followed by a late freeze or a mid Summer hailstorm and there goes that years crop. Late freezing in the spring has devastated crops in the Pac NW in recent years.

ELPF: P is for produce some of your own food, F is for fireproof your residence.

So what do you all suggest for those us us with wood siding? What's the most cost-effective option? Hardi-Plank is one thing that comes to mind, but are there better options?

Assuming your roof is ok, I would take care of your flammable vegetation within 30 foot minimum, 100 feet when you can, and spend the money on other things. Maybe get a galvanized stock watering trough or other water storage device, and a Mark II or similar portable pump if your fire department is not really close. I'm in the same situation, but the fire station is only a mile away.

We have fruit and nut trees on drip irrigation as our 'edible landscaping', so that's how we take care of vegetation within 100 feet of the house. The rest is open pasture out to around 1000'. And we are in the northern tip of Virginia, so we are not as hard pressed (yet) for precipitation as the US West. It's another story entirely, however, south of us; most of the rest of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida are in various categories of drought (or at least unusually dry), even in the middle of winter. See the Drought Monitor for details.

FD is < 1mi away here too, I'm not worried about their responding if it is just my place. The scenario that worries me is a forest fire sweeping through the mountains and into town - they would just be overwhelmed with that. We're not near the periphery of town, so we'll probably be OK. Still, I am hoping to be able to afford to do some remodeling in a few years, and I might want to go ahead and replace the siding anyway (and use that as an opportunity to beef up the insulation while it is accessible).

WNCO,

First, get rid of composition ngle or shake roofs and go to metal.

Second, clear around your house and buildings. The California Dept. of Forestry used to recommend 30'; they now recommend 100'.

Third, have sufficent water stored (or in a pond) to be able to start initial fire control or to provide water to fire tankers. I live beyond the "exburbs" and in the boondocks. We have had fires around us and it always scares the crap out of us. But, it is great to see a helicopter dipping out water from a pond on the corner of our property and know that that water could be used to save our place.

Lastly, I'd worry about the siding.

BTW, we also have a written evacuation plan so we won't have to waste time deciding what to take or do.

Todd

Thanks for the advice. No shake roof, I'm not insane! I would like to replace the shingles with a metal roof, hope to be able to do that in a few years.

I've got a few trees too close to the house that will need to go eventually. I hate to do that though, we do benefit from the shade. Since we're not so arid out here compared to CA, I think we're safe with 30', and I might even take my chances with less with a few of the really important shade trees.

hardi plank is the way to go

As for your shade trees, I put two impact sprinklers on the roof of my house during fire season and they take care of my shade trees. well I hope they do, as I haven't had the opportunity to load test this contraption.

Northern California is great but can be stressful during fire season

Hi Earl,

Ain't that the truth. In fact, it can get downright surreal. There was a fire on a ridge a few miles south of us a few years ago. We got out lawn chairs to watch to be sure it stayed going west to east and not north toward us. It was wild watching the insane four engine water bomber pilots come in at a 45 degree glide path and fly down toward the valley. Those people have more guts than I'll ever have. At the end of their run, they had to do a quick pull-up or crash into the ridge on the other side of the valley.

There have been lots of other fires over the years but you never get used to it.

Todd

Defensible space. Depends on one's surroundings. Non-flammable horizontal surfaces. Beware of flammable underpinnings - i.e. decks, porches, carports. Here's a controversial one: DO NOT EVACUATE - STAY AND DEFEND YOUR HOUSE! Have the ability to maintain water pressure when the grid goes down. Sprinkler on the roof is a great idea. Get to know the local firefighters - make sure they know where your house is. Have a clear and accessible driveway. Do not have evergreen shrubs near your house - they become incredibly powerful blowtorches when aflame. Also no woodpiles, gas tanks, lumber or any other piles of flammables. This includes automobiles.

Imagine every single plant and object around your house on fire at the same time - could you stop that from catching your house on fire?

Hi G2S,

A controversial view, as you say. I can appreciate the strong desire to remain with your property and do whatever you can to protect it, but you're really putting your life at great risk and at the end of the day, your life is worth far more than any worldly possession. Collect up the photos and any other cherished belongings to take with you if you can (but only if time permits), close the door and let your insurance company worry about the rest.

CNN interviewed three guys who stayed behind to protect their adjoining properties in one of the recent California fires and although they were well equipped to fight the fire and executed their game plan flawlessly and thankfully came through it OK, even they admitted it was foolish to have remained behind. So, I agree, do whatever you can to minimize the risk to your home, but if authorities are calling for your evacuation, I would suggest to you the only sensible option is to leave.

Cheers,

Paul

I found this post most informative and well written. Thank you!

Good article. A big factor that it seems you did not cover is the early spring rains at altitude in regions that depend on snowmelt for irrigation.

One of the most catastrophic events in these regions is a warm spring with rain in the mountains that melts the snow. This leads to devastating floods followed by drought later in the summer. It seems to me looking at your graphs that these events may become the norm not the exception over time.

Thanks. You are correct about warm spring rains on snow producing floods. With irrigation directly from streams, mid summer flow is dependent on contributions from above around 5000 ft, depending on latitude, if I recall correctly. Irrigation from reservoirs can fill and capture some of the flow, but it is much better to "store" that water on the ground, rather than having to pass it through the system.

I've also heard that both less snowpack accumulation overall and earlier melt from higher than normal temperatures (before irrigation season) are also other aspects to this problem;

http://www.news.cornell.edu/releases/Jan97/water.hrs.html

http://www.usatoday.com/weather/climate/globalwarming/2008-02-01-water-c...

http://ccc.atmos.colostate.edu/newsapr1.php

The essay models above predict precipitation, they don't specify form. I don't think we'll see near the pack in the future either.

We've been very fortunate this year, after years of precipitation deficits, to get the snow we have. For lower elevations, the form difference has been often just a few degrees. The storms come in from the Pacific, moist and relatively warm.

Sea levels get all the attention, but rainfall changes are the real threat of climate change. Africa is going to be at severe risk, with about 95% of their agriculture being rain-fed. A study from Stanford estimates that rainfall disruptions triggered by climate change may reduce the yield of crops like maize by as much as 30% in Southern Africa over the next two decades.

Excellent article, Doug, thanks.... and GliderGuider has just made the comment I was going to; precipitation changes are going to be HUGE compared to sea-level rising. It won't be a matter of people getting their feet wet, it'll be famines.... and here I include the loss of glacier-fed river water in some of the world's most populous areas.

Every time some idiot asks "what if a warmer world will be better?" I cringe; we, the rainforests, the coral reefs, and our economies are all evolved for a fairly narrow range of conditions. We won't simply see productive farmland moving north, we'll see what we're starting to see: significant contextual change. Everything we're used to is well-tuned for the conditions which have been 'normal' over millenia. Yes, the world, life, and even humans will try to adapt, but it won't be pretty.

One thing. In the article he says that trees in West survive in the Summer by tapping groundwater, and that in the future this will become more difficult. surely if that graph is right and rainfall in Fall, Winter and Spring is considerably higher there should be a more water in the ground for trees to tap come Summer, and they should survive.

I believe it comes down to the tree species, their density, and the fact that summers are predicted to be both drier and warmer than normal. Well spaced Ponderosa pines will fare much better than tight stands of fir.

Which is behind much of the current push for forest thinning. The thinned stand is much better able to survive, and produce higher yields, while lessening fire danger. Additionally, thinning can allow more snow to reach the forest floor and reduce interception losses, yet still provide shade to regulate melting.

What is an 'interception loss' and how does it reduce moisture levels?

Interception loss refers to the amount of precipitation, both rain and snow, that is captured by the forest canopy and evaporates. It varies with respect to tree species, and storm amount/intensity.

Speaking from experience in the NE, rather than the west - in a dense coniferous forest, much of the snow ends up on the tree limbs, not on the ground. Imagine those pretty Currier and Ives pictures. Of a 12 inch snowfall, as little a 3-4 inches, depending on temp/wind/humidity, will accumulate under dense evergreens. This snow largely sublimates - goes directly from solid to gas into the air. Never has an opportunity to recharge groundwater.

RE tapping groundwater. In the eastern deciduous forests, if there is a wetter than normal spring, the trees will put on more foliage than normal and this will potentially exacerbate any summer drought conditions (see Atlanta 2007) because the trees are sucking out the ground water at a greater rate than normal lowering the water table and drying up the lakes. If the wetter springs/drier summers situation holds for the east, this might bring about more megafires in areas that are not accustomed to this type of disaster.

In southwestern BC, where I live, we're starting to see failures of mature balsam fir, with the moisture stress of dry summers seen as the cause.

It seems to me that an answer to some of these problems is in the making. The advances in cellulosic ethanol mean that, quite possibly, we can afford to start pruning the dead trees, and most of the flammable foliage out of our forests. By using fast pyrolysis methods we will, also, produce biochar which aids in moisture retention, and allows for the utilization of much less fertilizers.

Oh; Great Article. I feel like I learned a lot.

with biomass yes it just may be profitable for loggers to clear out the underbrush when they log. that would greatly cut down on the fuel.

Biomass to ethanol is a possibly feasible future technology, but biomass to electricity is an existing technology with two plants currently selling power to the grid in my part of northern California. A third plant in Weed, Ca. is going through CEQA.

Yes, taking out dead trees would reduce the fire danger and provide feedstock for gasification. However, the forest service put out a contract bid a while back to take out dead trees and there were no takers. Maybe the situation has changed economically, but you have to have a cost effective way of removing the trees.

Of course, you're right, Calguy; it's all about the economics.

The economics (and, the technologies) ARE, however, changing. Maybe, Next Year, there will be a Taker.

It's not just about the economics. The quantity of dead wood in some places has overwhelmed the industry's ability to take it out.

The current outbreak of the mountain pine beetle (MPB) in British Columbia is an example of the effects of climate change on forests. The warmer winters and longer growing seasons of recent years are the proximate cause of the extended outbreak. MPB larvae overwinter under the bark of pine trees. In the early stage, the larvae are vulnerable to cold winter temperatures, but late-stage larvae can withstand temperatures close to –40ºC. With a longer growing season, more larvae reach the cold-hardy stage before winter sets in, and with fewer cold winters, more survive through to the following year.

Huge areas in the centre of B.C. have close to 100% kill of lodgepole pine, the favoured host of this beetle. Over 4 million hectares, about 10% of the province’s total land area, have been classified as moderate to severe kill for lodgepole pine, a species used for decades in replanting interior forests. B.C.'s forest service estimates that about 80% of the province’s mature lodgepole pine will be dead by 2018. Almost any flight over the southern part of the province where the ground is visible shows masses of red, dying trees and brown dead ones. By 2005, over 400 million cubic metres of wood had been affected. That's just too much to take out over a few seasons.

As Doug Fir suggests, the risk of fire in beetle-killed forest is increasing. I'm glad I don't have to fight these fires for a living, because the signs point to worsening conditions. When these forests burn, the wildlife are lost and decades worth of carbon sequestration goes up into the atmosphere in a few days.

In speaking with state foresters for the preparation, BC and the mountain pine beetle was cited time and again. Thanks for your discussion.

I don't see how it will ever be economical to put roads into the forest, selectively cut dead trees, gather underbrush - haul it out of there to some (as yet non-existent) cellulosic ethanol plant - make your ethanol (with hopefully SOME positive return on energy - and netting a product that has less btu's than the fuel you've expending doing all this cutting and hauling) - and then truck (since ethanol doesn't do so well with pipelines) the ethanol to blenders AND take the biochar out to farmers

Doubt very much the numbers will add up

and your point about no takers on the contracts for dead tree removal is spot on - it isn't economical unless they can clear cut - so it's essentially a non-starter on a commercial scale

Might be a good make-work project in a Depression.

we don't need roads in many instances and they can cut new trees, dead trees and truck the underbrush out for biomass. alot of times I beat they don't cut the underbrush and what is needed to be cut just stays in a pile sitting there.

Taking trees out of the forest depletes the soil

At some point we just need to give up on the whole cars-and-consumer-culture thing. It's way past time for a major change in how we live. There's no way around it. Liquid fuels are not the solution, they are part of the problem.

The zeroth commandment:

Thou shalt not exceed the carrying capacity of thy ecosystem.

Very interesting reading. Thank-you!

I worry about the effects of climate change on smaller scale urban agriculture. For example, when your rain barrels don't fill up enough, or when the summer night temperatures don't sufficiently drop that's a problem. I am hoping the latter just means a shift in the growing season dates.....

It is informative to look at crop modeling for climate change and the difference between scenarios "with adaptation" and "no adaptation." Of course yield losses are less with adaptation, but the assumptions in adaptation models are not credible in my view.

For example, let's say temperature rises at 0.3 C per decade, with various implications for rainfall patterns, etc. The adaptation models go like this: teams of agronomist take account of predictions for climate change in various regions of the world and develop new strains of crops for the future climate ahead of the impacts. They then are able to deploy these to the world's farmers, who are able to continually incorporate new seed varieties and cultivation practices as the climate changes unfold.

Then, year after year, they must do it again, non-stop, for hundreds of years.

And yet, even with all these rosy assumptions, yields are expected to decline.

I recently conducted this interview, heavy on the cryosphere, but we get into rate of change and ecosystems too:

http://www.energybulletin.net/40619.html

I think it will be more than just running harder to keep up.

New varieties have been developed for incremental changes, and will fail in the face of hard drought.

Other problems include loss of yield with the newer reduced moisture varieties, and having to predict what the seasonal moisture regime will be before planting, whether to go for gusto and plant a high yield variety, or play it safe and sacrifice yield . In fairness, there is work to varieties who will produce in both normal and reduced moisture conditions, such as the current test of Espanda wheat in Australia.

But it highlights that up until recently, work has centered on yield at the expense of root systems. New varieties have taken from 7 to 15 years to be deve1oped, if I recall correctly. Worldwide drought and declining grain stocks are pushing for the adaptation quicker.

Gee, I thought that President Bush solved the forest fire problem with his "Healthy Forests Initiative":

http://www.sierraclub.org/forests/fires/healthyforests_initiative.asp

Ronald Reagan, America's greatest president since Herbert Hoover, has also made major contributions to protecting the world's forests:

"If you've seen one redwood, you've seen them all."

- 1979

"Trees cause more pollution than automobiles do."

- 1981

"A tree is a tree. How many more do you have to look at?"

- 1966, while opposing expansion of Redwood National Park

And let us not forget James G. Watt, Reagan's Secretary of the Interior:

"We will mine more, drill more, cut more timber."

- James G. Watt

More memorable quotes from Saint Ronnie:

http://dkosopedia.com/wiki/Quotes/Ronald_Reagan

This scattergun ad hominem attack isn't shedding any light on the issue, and the Sierra Club isn't the most unbiased source for forest thinning issues. It is a physiological fact that trees develop thicker, fire resistant bark more quickly when they are given room to grow. A harvest operation designed to maximize profit shouldn't be brought up to debunk the results of a thinning designed to improve fire resistance.

I think that I shall never see

A billboard lovely as a tree.

Perhaps, unless the billboards fall,

I'll never see a tree at all

That KiOR project that was talked about in Robert Rapier's last ethanol post (At last, Vinod Khosla, and I see eye to eye) seems as if it would be aiming in this direction.

How many tons of biomass (per acre) could you get by a good scientific "Pruning" of these forests. How many acres are we talking about?

"good scientific Pruning"? From what I've seen out here in the West - that is code for allowing big timber to get in and cut down everything ("it's too expensive to do selective cutting" they whine)

"Healthy Forests Initiative" means "Free Pass To Go Cut Down Public Forests" - and the taxpayers get to pay to build the roads in

I can't IMAGINE a scenario where your biochar scheme has a positive return on energy for a minute - how much fuel does it take to harvest, transport etc. the trees, turn them into biochar, and finally transport that product to the fields?

The point is: with 100 gal/ton returns selective pruning IS financially viable. I'm clueless about the KiOR technology, but some of these proposals would return a certain amount of biochar as a coproduct. It would just be a welcome bonus.

The problem as I see it comes back to collection and transport costs. The forest is undeveloped, often poor roads or skid trails with long distances involved. Collection of the slash is labor intensive on steep slopes.

The best source of forest biomass is at the mill, but increasingly I've found mill wastes are already contracted for waste to energy plants. Even here they run up against transport maximums of 50 to 100 miles on good roads, depending on the premium the mill wishes to pay to get rid of the waste.

I would also add that taking biochar out of the forest decreases soil fertility, which the trees need to remain healthy and reproduce. The production of biochar could result in speeding up desertification.

Then leave some of it IN the forest.

Look, if we can figure out how to drill down 7,000 ft beneath a storm-ravaged Sea, we can figure out how to trim some dead/diseased trees, and ground foliage out of a forest.

The reward is much different

doug fir -

You've touched upon what I think will turn out to be the fatal flaw in many of these waste biomass-to-energy schemes: simple material handling, transport, and processing constraints. No rocket science here, just some very stubborn facts of life associated with trying to 'harvest' a highly dispersed and difficult material from relatively remote locations.

Take a high-yield crop like corn. It is grown at extremely high density in nice neat rows that are easy to harvest on a conveniently located farm using highly developed mechanical techniques. The corn gets transported over paved roads to conveniently located storage silos. Piece of cake.

Now take something like trying to harvest dead trees, underbrush, etc. One will have to travel to relatively remote areas, bring heavy equipment off-road, and will have to use far more tedious and labor-intensive collection techniques (assuming one doesn't want to also destroy the good trees). Then one has to transport that material all the way back to some receiving station, where the material will have to be processed (probably first chipped in a large tub grinder) and then finally sent from there to the cellulosic ethanol plant. Not such a piece of cake.

By observation: which of the above two harvesting scenarios is likely to cost more in terms of dollars per ton of usable material?

Technically, there is no doubt that it can be done, but the questions become: is it worth it from an economic standpoint? How much energy will be consumed to extract a final unit of usable energy?, and how badly will it impact the environment?

I have some doubts as to whether the big forest product companies are even half-seriously contemplating such forest waste-to-ethanol schemes. And trust me .. they have many highly competent people trying to figure out how to get as much value out of an acre of forest land as possible.

"And trust me .. they have many highly competent people trying to figure out how to get as much value out of an acre of forest land as possible."

Agreed. Whether it's plywood, chipboard,(OSB), or the new company R2 is going to that increases the durability of softwood lumber, they are looking. The U of ID, with a prominent forestry school, heats some of the campus via steam tunnels from rail-delivered lumber mill waste.

If the climate scientists want some of the skeptics to take their models seriously they should use them to make some predictions that are testable in the short term.

Instead of pointing out the occasional drought or other unusual weather after the fact as evidence of climate change how about doing something useful like predicting them ahead of time.

I'm sure the farmers in the southeast would have appreciated knowing an extended drought was on the way before they decided what to plant last year.

Knowing that this winter would have heavier snowfall that usual would have allowed cities to stockpile extra salt before the prices skyrocketed.

So climate science will be beliveable when it can predict the weather this month? You are confusing short term weather and long term climate trends. But feel free to ignore all that has been learned about what is happening - it really doesn't matter if you believe it or not.

An excellent point for all the AGW deniers - it's happening and will affect the planet whether they choose to believe or not

and from just the small sample here, they will certainly choose most vigorously NOT to believe the evidence....

"but...but...SUNSPOTS! but...but...it was COLD in North Dakota this year! How do you explain THOSE facts hmmmmmm?"

tiresome really - but a few seem to me to have to be paid efforts, we know Exxon Mobile engages in this sort of thing and there were those military staff who were paid to go online and spread disinformation about Gitmo - so it's not really tinfoil hats all the time...

Umm, weather channel? 15 day forcast anyone, lol.

It's been done already, IPCC reports from years ago have said climate change will lead to more drought and extreme weather events, aka climate variability. What type of weather have we had lately the past few years.. ummm...

it seems to me like most CC deniers haven't even looked at the evidence against their views, very open minded people. They just stick their hands in the sands and point to the sun and volcanoes like tribal creatures.

CC deniers are essentially scientific vandals just throwing stones and tagging buildings.

Umm, weather channel? 15 day forecast anyone, lol.

It's been done already, IPCC reports from years ago have said climate change will lead to more drought and extreme weather events, aka climate variability. What type of weather have we had lately the past few years.. ummm...

it seems to me like most CC deniers haven't even looked at the evidence against their views, very open minded people. They just stick their heads in the sands and point to the sun and volcanoes like tribal creatures.

The average climatologist probably has an IQ of 149 and lives to incorporate as many variables as possible into their models--sunspots, orbital cycles, urbanization...etc. What amazes me is folks who read a few web sites and think they have stumbled upon some obscure but powerful factor that thousands of highly intelligent and dedicated people who above all else are paid to sort out how the world works have never thought of.

A year long drought can hardly be called a short term weather event. I don't see how expecting some practical predictions from their models is too much to ask. You don't even to need to be a climate scientist to see how the ice caps melting in the arctic could lead to colder and snowier weather in eastern and central Asia.

Is it intuitively obvious to everyone that a warmer climate in eastern Ontario will lead to greater winter snowfalls? I don't think so.

Sorry, a one year drought is a short little blip to us climatologists, just weather as far as we're concerned. A proper drought is 50-100 years long in Western North America. Europeans haven't see what this continent can produce (except for the Spanish in the SW USA), Native Americans have. Specially the Anasazi, farmers of the Upper Missouri Valley and probably the Mississippians at Cahokia. It's the 50-year droughts that we climatologists worry about, they break civilizations.

See:

Woodhouse, C.A., Overpeck, J.T., 1998. 2000 years of drought variability in the central United States. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 79, 2693-2714.

Stahle, D. W., Cook, E.R., Cleaveland, M.K., Therrell, M.D., Meko, D.M., Grissino-Mayer, H.D., Watson, E., Luckman, B.H., 2000. Tree-ring data document 16th century megadrought over North America. EOS 81, 121-123.

North American drought: Reconstructions, causes, and consequences

Edward R. Cook a,⁎, Richard Seager a, Mark A. Cane a, David W. Stahle Earth-Science Reviews 81 (2007) 93–134.

St. Jacques, J.M., B.F. Cumming and J.P. Smol. (2008) A 900-year pollen-inferred temperature and effective moisture record from varved Lake Mina, in west-central Minnesota, USA. Quaternary Science Reviews, doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2008.01.005.

> Instead of pointing out the occasional drought or other unusual weather after the fact as evidence of climate change how about doing something useful like predicting them ahead of time.

From the 1995 IPCC Summary for Policymakers;

From the 2001 IPCC Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: North American Region

The problem is that predicting a chaotic system such a weather is like predicting which number a roulette wheel will give. If you can observe until the ball has almost landed, you might be able to make a usable prediction (i.e. win often enough to cause the casino to go bankrupt). The climate models give results like the mathaticians who can estimate the casinos monthly profits, but can't tell you which customers will be lucky.

There are agencies involved with moderate range climate prediction. Look up NCEP (National Center for Evironmental Prediction). They make probablistic forcasts for a month to perhaps 18 months. They don't run weather models, like the climate folks, they look at conditions like observed sea surface temperatures, and soil moisture etc. But these can only produce moderate statistical predictions, like this coming July there is a 45% chance of it being

among the hottest third of recent years. This is still useful information to the farmer, and hydrological manager -but it only slightly improves the odds of getting the planting decision right.

This was forecast by climate scientists.

NASA GISS 2007

Really, the introduction to this story by Nate is scary, "if climate change ends up being real and urgent." Nate when does it become real and urgent?

Great article, Doug.

I don't know. I have my hands full focusing on addiction and the problems with economics....;-)

Clearly the climate is changing. I believe this is at least partially and possibly largely due to human influence. I just don't have the breadth of reading experience on the topic as others and have chosen to spend my time in other areas. Based on the vitriol whenever this topic is posted on TOD, I just wanted to point out that climate change, human caused or not, will impact energy and food production. If climate change standard deviations accelerate already then the impacts will be even greater. Tangentially, I am co-writing a paper on the standard deviation of biofuels, which climate variations can/will certainly exacerbate.

If we are seeing increased intra-seasonal variations, such as wide temperature or precipitation fluctuations in northern climates during the winter, that's strong evidence that the climate is becoming more chaotic.

Which would mean it's becoming more "real".

As to how urgent it is ... we'll see how crops, competitors, and assistants (like bees) behave during 2008 and 2009 in response to changing weather patterns.

How do bees respond to changing weather? I thought the problem with bees was CCD/mites...? Has that been shown to be linked to climate volatility?

I don't know. That's why I said we'll have to see.

But I can guess that bees do respond to changing temperatures. The British Beekeepers Assn FAQ says that bees (1) over-winter through the heat generated by their bodies and (2) that colony populations can be as high as 35,000 in the summer, and as low as 5,000 in the winter.

I would imagine that bees are accustomed to adjusting their behavior patterns according to changes in temperature, like many species. There would be biological cues that say, "Getting warmer, no need for us to generate excess warmth anymore", only to find that the warmth was short-lived and the temperature drops below zero again ... which can't be good for the hive's operations as a whole.

Also, increased environmental variation is a Darwinian process.

I know that during a recent spat of warmth last December, the Japanese ladybeetles and Box Elder bugs around me became active again. Then it got colder and they disappeared again.

But like I said, we'll see. But the forecast looks dicey just from a natural selection standpoint.

Some folks have pointed out that bumble bees are also dying. Last year, we had an early warm spell here in the mountains, then a hard freeze. After things warmed for summer, I spent some time looking for bumble bees. They used to be everywhere on the clover and wild flowers. Not last summer. Was it CCD or was it weather? I wish I knew, but bumble bees are pollinators too, just like the honey bees which are trucked around to pollinate various crops, only the bumble bees do it for free. The bees emerge from hibernation timed to feed on the flowers. If the timing gets mixed up, the bees starve. Or, around here, they have only the Laurel and Rhododendron to feast on, which happen to be mildly toxic to bees. I watched a few that were wandering around on the ground, unable to fly. I found very few in all..

E. Swanson

As to how urgent it is ... we'll see how crops, competitors, and assistants (like bees) behave during 2008 and 2009 in response to changing weather patterns.

It's not just bees dying of mites and CCD, now it Bats.

Mass bat deaths in NY and Vermont baffling experts

http://www.boston.com/news/local/vermont/articles/2008/01/30/mass_bat_de...

Which Sign Number are we at now? Have we hit the 7th?

NOAA issues seasonal outlooks. You can get them here .

Hello Doug Fir,

Well done! It would be interesting to know current aquifer depletion rates plus the addition of even more wells with even deeper, ever longer pumping periods trying to offset ag and population demand growth for food. We might expect to find a HL H20-downslope even more precipitious than the C+C HL downslope; a massive superstraw sucking effect trying to fight against climate change perturbations.

It is an opposite strategy when compared to crude extraction; the last oilwells are drilled at the anticline peak [see Ain Dar for example] vs H20 pumping wells have to go ever deeper and outward to the aquifer geoboundaries to extract the last drops.

For example, take the massive mid-US Ogalala Aquifer: what are the pumping projections going forward with rising energy costs? How will this effect irrigation costs and harvest yields? At what point will the aquifer be so deeply depleted that pumping water from the Great Lakes south be the cheaper alternative?

Bob Shaw in Phx,Az Are Humans Smarter than Yeast?

Bob,

I can't answer your questions on the Ogalala Aquifer, but the fight for water is sure at boiling point. There just doesn't appear to be any new sources, and existing rights are coveted. In the 1984 irrigation survey, approximately 44.7 million acres were irrigated, having fallen in the late seventies, presumably due to the inflating energy costs. The 2002 survey shows we are over 55 million. I don't think we will that significant an increase again.

Proponents cite the increasing value of grain will shift more irrigation to grain, but it gets more expensive each year. Another example of receding horizons, IMO. Theoretically, there is room for increase, in that 49% of US present irrigation water is currently used in the more inefficient gravity furrow and flooding systems. But the cost to switch is substantial. In the 2002 survey, unable to finance, landlord won't share costs, or improvements don't justify cost are the major barriers cited for not making improvements to reduce water or conserve energy.

Thxs for the reply, Doug, mucho appreciated.

The two classic quotes for water are: whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting over, and water flows uphill to money. I suspect the legal problems and power grabs over 'liquid gold' are just beginning [example: the Tennessee-Georgia border dispute for river water].

I didn't catch any mention in the article on the feedback loop between rainfall variability and runoff. With year round gradual precipitation (as opposed to dry spells and storms) more water gets in to rivers and dams, hence more water is available for irrigation. Like the solar powered flashlight it works best when it's not needed so much. Clearly dryland farming will have to get more resilient, for example going back to primitive cereals or grazing goats instead of sheep. With oil depletion and irrigation cutbacks intensive farming may not be able to make up the yield shortfall. Instead of chicken and fries expect barley and goat on the menu.

Somebody should do a trial of forest thinning as a biofuel feedstock. The portable rendering plant already exists but so far I haven't seen any portable mini-refinery that can make fuel suitable for modern machinery.

Hi,

Back in about 1996, I went to a talk by ecologist W. Schindler on fire and boreal forests. He was the scientist who did the whole ecosystem studies on phosphate eutrophication in lakes and acid rain in lakes. He suggested that there were going to be some nasty consequences to global warming that we weren't cognizent. He also suggested that the positive fallout of moving agriculture north wasn't going to happen.

Here is a passage from Globe and Mail.

"Unfortunately, Dr. Schindler's case is strong and getting stronger. Take global warning. Scientists have long forecast that warmer temperatures could literally dry up and undo the boreal faster than any other ecosystem in Canada. Dr. Schindler, of course, has already documented its beginnings in Northern Ontario.

In the last decade, warmer temperatures and drought raised air temperatures by 1.6 degrees near Kenora and accelerated water loss by 50 per cent. A drier landscape invited massive forest fires that scorched the same land twice during a 10-year period.

As a consequence, a mature boreal forest of jack pine and black spruce was wiped out and failed to recover. Now bare bedrock lies exposed in an area once covered with mossy mats 20 to 50 centimetres deep. Much of the area around Kenora no longer looks boreal at all but now resembles aspen parkland.

His take on climate change remains pragmatic. "Look, it doesn't matter if a 20-year warming trend is caused by greenhouse gases or a natural cycle. But the warming is pushing the boreal system to the edge with burning forests and by amplifying the effects of acid rain and ozone holes and logging. We have to adapt our management schemes to give it enough slack to adapt."

http://www.carc.org/whatsnew/writings/anick.html

Now, during the last glaciation, most of the top soil in northern Canada was pushed into the northern states of the USA. So the top soil is REALLY thin. If you have too many hot fires, you end up with bare rock. And that may be one of the major consequences of global warming. Our Agricultural zones will move towards the poles but there may be either no soil or really crappy plotzes. Thus agricultural output has a real potential to fall.

Not to frighten you.

Charles

During a warm, dry period about 4,000 years ago, the prairie extended as far east as International Falls/Fort Frances and the Kabetogama Peninsula was scrub steppe. The Sheyenne Delta in southeast North Dakota blew up into huge sand dunes. One of the fears after the 1999 500,000 acre Boundary Waters Canoe Area blowdown was that dried out trees on the ground would catch fire and sterilize the thin soils.

Our permanent home is in the southern extremity of the boreal forest, near Orr, Minnesota. I've been watching the vegetation closely. A few years ago spruce budworm took out almost all the balsam fir in our area. White pine blister rust infestation rate has been increasing. I'm seeing more burr oaks, a rare tree here. Every winter that it doesn't get to at least 40 below, and we've had a few of them now, makes me worried. I keep telling people, cold is good, cold is good. I came across some 5 foot tall switchgrass growing near Pelican Lake. That's a C4 plant that likes heat.

When it comes to moisture, it isn't the absolute value that counts but the "water budget," which is the ratio of total expected moisture accumulation divided by potential evaporation. That's why 30 inches in Texas is the equivalent of 18 inches straight north on the Canadian border.

When people talk about the corn belt moving north because of global warming, they are not taking into account the importance of the water budget. I tell people it's not the corn belt but the milo (grain sorghum) belt that will move north. And, like you point out, the soils are very different. It's hard to grow corn on podsols.

Fighting Western wildfires are very fuel intensive operations. If you think they're bad now wait until there are spot diesel shortages.

You just made the case for hybrid trucks.

Without parents planning to have smaller families, it is hard to imagine a world where people would not have to cope with a desire to increase energy production. They will utilize the resources near them to make their lives more comfortable. I do not believe the sea has risen a foot since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, yet continental ice sheets melted and the sea level rose many feet without industrial use of hydrocarbons over the course of thousands of years. According to these theories of global warming if you warm the atmosphere the ice caps melt and the sea level rises. Was there increased water vapor in the atmosphere at higher temperatures that does not result in global flooding? What is the consequence of pumping aquifers until they are dry for domestic and industrial use? Has this not resulted in coastal flooding? What is the impact of damming rivers on coastal flooding? If you can show me half a foot of sea level rise in the past 50 years I might not panic. My generation will be gone, others might adopt the one child rule and move to higher ground.

You know, as well as I do, that the sea level increase between 1900 and 1999 was about 6 inches, and that large short-term variations make this increase difficult to spot in the raw data. See, for example, this 1999 analysis of sea levels at Fort Point.

It is a tough sell to get the whole world to negative population growth. The Europeans have been going that route, importing labour because of the work age population decline, and if current trends continue their culture will be replaced by that of the immigrant population. Given those sorts of implications most ethnic identities would choose against that route.

I think twentieth century sea level rise was about 8inches 20cm IIRC. It is currently running about double that rate, and the rate of rise will increase substantially during the coming decades. Atmospheric moisture isn't really significant; on the order of a cm (.4inches) or so. It is increasing due to GW, as warmer atmosphere can hold more water. The question about pumping out groundwater is an interesting one. I (or you) will have to pose that one the realclimate, i.e. how is the manmade change of nonfrozen terrestrial water storage (groundwater and lakes) affecting sea level?

I really don't think I'd be that hard to get a European country at 0% population growth, through planned families, birth control, good education and tax incentives/penalties.. I mean whats the alternative, overshoot with famine, starvation ect?

Yeah firefighting nowadays is literally fighting fire with fossil fuels. Big fires mean more crews and longer fire lines. GW is adding more forest fuel with a higher energy release component. That takes more water to bring fuels into a moisure range that's suppresive. The truck or aircraft to bring that water is more expensive per trip. Chances are water sources are tougher so the trip is farther. If resources get overwhelmed it's simply evacuate or disengage and protect the exposures in many cases.

One of the major problems with irrigated land is sodicity. The salts in well and river water accumulate in the land and render it less productive. There is pretty much no substitute for nice rain water. If much of our land in the U.S. is dependent on rain fall, climate change would be a very important topic to me.

Insects are going to adapt quicker having much shorter life times and higher numbers.

Theres that troublesome vector borne disease thing too.

There is a significant amount of energy involved in hygiene and health care

It depends also on how the competitors, predators, and food supplies for insects adapt as well.

Won't the warmer winters in the mountains mean that there will be less storage of winter precipitation in the form of snow? Surely this implies that more man made storaqge of water is needed.

WRT to species mix in drought areas; Trees aren't passive! In Portugal they grow a lot of Eucalyptus stands; the Eucalyptus not only has a lot of volatile oils in the leaf litter and trunks, its ability to recover from fire both through vegetative regeneration and post-fire germination exceeds that of the native and N. American imported pine species. In effect, the plant uses creative destruction through fire to alter the habitat to its benefit.

It is likely that the species mix in the Western US will be demonstrating the same thing; the more small fires are retarded, the larger eventual fires will see a faster change in species mix in favour of the drought-tolerant species colonising heavily burnt nutrient-depleted soil.

The success of the eucalypt is resented in places like India where they demonise it, claiming it lowers water tables more than well pumping. So far as I can tell nobody has been able to make a cheap fuel from essential oils (terpenes) in flammable plants. A pity since that way they could be harvested rather than deliberately burned.

Down Under there is a lot of conflict between rural fringe dwellers and the parks service over burnoffs. Even healthy people suffer respiratory distress from sub 5 micron smoke after several days. I sent an email to the EPA but was told to get lost. One day a successful lawsuit could remove the burnoff option. That's another reason to mechanically thin forest rather than burn. I guess that would favour the non-target species.

I'm not sure any tree or seed-pod could survive one of these mega-fires. They're not like the usual forest fires that clear understory and facilitate tree growth -- they incinerate everything.

The Earth is unique in our solar system in that it has maintained a very narrow average global temperture over several billion years. The other nearest planets, Venus and Mars, have not.

They have acted like mechanical systems, ones that ran out of control towards either a permanent hothouse or the other, running out of control towards a permanent icehouse.

Both states are now static and as permanent a state of affairs as any planet could be in, barring some collision with an external body to knock them into another condition.

The Earth is alive. This is what has protected Her all these billions of years. Her biologically dynamic relationships have compensated and regulated Her temperature low these many eons. Mars and Venus are Deaf, Dumb and Blind by comparison. They were forsaken to their respective states many, many Moons ago. The Earth was blessed with the Axis Mundi: the Economy of Ecology.

Humans are undoing this gift as we speak. They probably won't destroy the entire system dymanic, but it looks like they will set it back to a far more primitive state for many milleniums. Enough, hopefully, to wipeout any trace of their current folly. Humanity deserves little more for it's inherent hyper-individualist greed and short sightedness. The real template of all economic 'theory' is Ecology. An ultimately aesthetic and intricate web of feedback loops, developed over many years of trial and error in Living Systems, not static mechanics.

Ah, but humans are so smart, they stole fire from the Gods, once upon a Time. Nothing can stop them from their Manifest Destiny to become Masters of the Universe. The Force (i.e. 'The Market Place' guides their Every Step) and is Infallible.

Fantasia had the metaphor dead on.

Mickey will save the day by having a Broom haul his Water.

Life is Good.

Robert Frost:

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To know that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

Excellent article, interesting to read the problems of fire on forests in the US. As an Australian I am well aware of forest fires and their threat. I am interested in the potential for eucalypts to take over from your native trees.

I understand that eucalypts are commonly planted in the USA and elsewhere in the world.

Eucalypts are also very fire tolerant either surviving a fire and then shooting from the stem or dieing but producing substantial number of seedlings. Either way they have a good strategy for survival.

Is there any indication that eucalypts are invading your native forests particularly those that have been burnt?

Hey C3827,

check out this: http://www.columbiauniversity.org/itc/cerc/danoff-burg/invasion_bio/inv_...

Climate Change related, dunno, but I'm sure Climate Change will certainly continue the trend...

Australia has had a long history of disasters due to introducing foreign species into its environment. I hope you're not suggesting that anyone follow the same disastrous policies.

I seem to remember reading somewhere that eucalyptus was used to drain swamps, similar to willow, so I assume it would also accentuate the effect of drought in any area where it is introduced. And while I'm at it I'll add that science and scientists are part of the problem, not part of the solution. We are smart enough to destabilise systems, but not smart enough to fix them, our attempts are likely to just make things worse.

Maybe we should get out of Nature's way and simply adapt to Nature's changes rather than trying to change Nature.

Nah, I was just showing a study how non-native eucalyptus in the US have caused lots of problems and are out-performing their fellow trees.

Burgundy

I was certainly NOT promoting the planting of foreign plants in the US. I am well aware of the problems of exotic weeds in native forests. In fact on Sunday we have our monthly weeding day in a local park near where I live. Its a never ending job.

In Australian many of our weed species are of African origin, similar climate, etc.

They'd really be clutching at straws with that one, because the 'increased yields' have been shown to be nutritionally poorer on a weight-for-weight basis ... you (you being an insect in the study in question) have to eat more of the stuff anyway. The plants grow more but give less useful food. So that argument's a complete non-starter.

I had a great observation with a rural farm (not forested) house fire a few years ago - the 'tin' shed 10 m away just lost some paint while the old wooden barn ~ 20 m away did an impressive flashover. Once the car tires caught on fire - well, there was a whole new experience.

The car gets put in the back yard & I'll be using fashionable tin on my house, thanks...

Thank you, Doug Fir for a great article and one of the best examples of nominative determinism I've ever seen.

Good article.

More forest / wild / other fires? France - not so, though newspapers, since a few years, regularly report summer fires as influenced by ‘global warming’ or climate change, and as being ‘very frequent’ or ‘more frequent than last year’ (this will almost always be true for some delimited region.)

See simple chart of burnt surfaces, from 76 here from this link (french) and for later years descriptions from here (french) showing that 02 (less than 6 000 ha.), 04, 05 and 06 (only 17 000 ha, lowest ever) were all low. 2003 was a disaster, with 62 000 ha - still less than some past years, such as 76, 89, 90.

Fire fighting organization has come under public attack. Under funding and defunding, particularly at a local level. Lack of fire breaks, violation of building codes, territorial management rules; forest, scrub maintenance, etc. Firefighters too distant - if they need to travel to the fire and take 10 hours...

I find it impossible to relate the damage done, the various firefighting plans (they appear to have worked quite well in the recent past) and climatic conditions. With the possible exception of the *recent* outlier 2003? There are probably ‘tipping points’ involved; the fire(s) runs because of a small lack of men and equipment.

For the US, eyeballing wildland acres from the National agency fire center, we see first high variation (from 1.1 million in 84 to 9.8 in 06.) Second, a trend, which I describe here so as to make it stand out: From 1960 to 1999, in only one year, 1963, were 7 million acres burnt (my word, a definition is not given) and only two years saw burnt areas of 6 million acres. For the last seven years (00-06) we see: 7, 3, 7, 3, 8, 8, 9. Like many such runs... a question of wait-n-see or scratch your head? (see France.) table 1960-06

What I find appaling in this thread is not the content, the detailed info it has, nor the message, nor anything, but the THEME. I recall a controversy in TOD Canada where some contributors were put down because they were putting an economic theme and that didn't contribute to the "energy discussion", so they were closed down.

Typical. The readers were only left with a closed down heated discussion and almost no clarification. They were effectively shut down and shut up.

But now, it seems that threads discussing themes other than energy is okay, as long as it is written by some specific contributors.

Where's the logic after all?

What a shame. What a lack of coherence and respect. For the contributors. For the readers. For transparency and diversity. I will continue to read TOD, but these past few months have been very bad for your rep. as far as I'm concerned. No longer I advise people to go to this site, as I did.

Is the doomer stress already hittin' on the editors of this page?

I consider anthropogenic forcing of climate change the front and center issue of energy. To discuss only energy supply while ignoring the consequences is foolish.

If you're worried about fires consider joining the local volunteer fire company and if you can't do that make a donation to the local vol fire and rescue dept/company.

Doug Fir,

I want to pick up on the short discussion of interception. It made a lot of sense to me that snow on the ground will add more moisture to soil than snow in the crown that will add more moisture to the atmosphere.

You said:

[I believe it comes down to the tree species, their density, and the fact that summers are predicted to be both drier and warmer than normal. Well spaced Ponderosa pines will fare much better than tight stands of fir. ]

I have no relationship to forests other than I love to walk in them. But, I have felt for most of my years that America's forests are managed by politicians and not silviculturalists.

Environmentalists have opinions about healthy forests and their thinking begins and ends with absense of human presence. Thinning forests and managing a healthy forest ecosystem is the work of experts who should have spoken up loud and clear that the environmentalist approach to protecting forests may lead to the demise of the forests they want to protect.

It is time for America to have an extensive and expert discussion about the threat our forests are under from climate change and misguided over-protection.

Certainly, the nation's academic community is best equipped to start and steer that discussion and it is time to get vocal.

Thank you, Doug Fir for your contribution.

John McCormick

>Environmentalists have opinions about healthy forests and their thinking begins and ends with absense of human presence. Thinning forests and managing a healthy forest ecosystem is the work of experts who should have spoken up loud and clear that the environmentalist approach to protecting forests may lead to the demise of the forests they want to protect.

I believe this is a tad oversimiplified. If anything, some sought to protect the forests by stopping forest fires, which allowed an accumulation of fuel. On top of that, global warming has led to drier and hotter conditions in the US West, also exacerbating hotter fires. Building roads into forests is in no manner the best means to manage said forests.