Four Billion Cars in 2050?

Posted by Stuart Staniford on February 18, 2008 - 10:00am

The Tata Nano will sell for about $2500 (US) in the base model, and get about 51 mpg (US). Source: Wikipedia.

This post is the start of an attempt to sketch out what an integrated solution to the world's food, energy, land, climate, and economy problems might look like. My basic goal is to get to a somewhat defensible story of how civilization could get to 2050 in reasonable shape, despite the problems of climate change, peak oil, global population growth, etc.and some of the requirements I saw as necessary in order to consider a solution viable:Since it's not possible for me to entirely solve this problem in a week of part-time work, I put this out as a hasty straw-man. Feel free to point out the parts of this that don't work, or where my ignorance of some of the relevant issues shows particularly badly. Of course, I don't make the claim that I can predict what will happen forty years ahead. Nor do I expect the global population to pay much attention to what I think they should do. Instead, the value of a scenario is to try to think through the general issues that society faces, and the value of an integrated scenario is that we can think about how all the parts fit together holistically, whereas usually they get projected separately by specialists, and even the obvious interconnections get missed by decision-makers (if we try to solve our fuel problems by converting food to fuel, perhaps the price of food might go up).

With that said, for the remainder of the piece I'm arrogating to myself sole authorship of all relevant international treaties and implementing legislation at the national level. Here's how I'd go about it. In this first piece, I've analyzed the overall requirements for the problem, but only fleshed out any detail on the population, economy, and energy sectors; I did not have time to write up my analysis of transportation and agriculture/land issues. I will do so in a future piece.

Then I looked at the energy sector and we saw that there are several potentially feasible ways to power civilization. They aren't cheap or easy, but solar, wind, and nuclear all have good to excellent EROEI and a fairly large resource that could be exploited. Solar in particular has the best learning curve historically (the rate at which price falls for each doubling of the installed base of the technology) and the highest growth curve and fewest barriers to early adoption (except cost). However, the renewable options are growing from a tiny base, and nuclear faces ongoing political resistance, so in the short term conservation and efficiency are critical requirements if we are to make it to the long term.

- Population: The global population is able to grow and go through its demographic transition with death rates continuing to go down. No die-offs.

- Economy: The world economy is able to grow on average over the period - modestly in developed countries, faster in developing countries.

- Carbon emissions: The global energy infrastructure will be mainly replaced with non-carbon-emitting energy sources by the end of the period, and residual emissions will be rapidly diminishing.

- Fossil fuels: I assume that peak oil is here about now but that declines will be governed by the Hubbert model (and thus will be gradual). I assume natural gas and coal are globally plentiful enough that climate policy is required to prevent their full use.

- Technology: I do not assume any massive breakthroughs - no technological miracles that solve problems in ways completely unknown or untested today. However, where technological sectors have long established rates of progress in key metrics, I extrapolate the metric to continue improving at the historic rate (eg the economics of solar power, or the yields/acre of agriculture are assumed to keep improving on the historical trajectory).

Still, if as a society we were serious and determined about solving our energy/climate problems, and we made the right investments, there seems to me little doubt that there are a number of feasible technical paths to a non-fossil-fuel energy infrastructure for civilization. Indeed, I argued that energy would likely become cheap again after a couple of decades of being expensive, once a renewable civilization was over the hump (the hump having been caused in part by failing to make more progress in the 1980s and 1990s).

However, there are many other resource constraints that we might hit along the way. So I want to continue surveying the terrain at a very high level and look at the automobile sector under the rough assumptions I outlined in Powering Civilization to 2050. In particular, how many cars might we expect by 2050, and how can we possibly power them, given that there will be less oil, not more, by that time. I think most readers would intuit that if society was wealthier in 2050, as I postulated, then if they possibly could, the planet's citizens would tend to drive more, not less.

But how much more? In my earlier scenario, I postulated a world GDP of about $350 trillion in 2006 dollars by 2050 (on a purchasing power parity - PPP - basis) which arose by assuming reduced economic growth in the near term due to problems of recession and energy constraints, but then renewed growth as those ultimately lift. Given the UN's medium population projection of 9 billion people, that gives a world GDP/capita in 2050 of about $28,000 (versus about $11,000 recently).

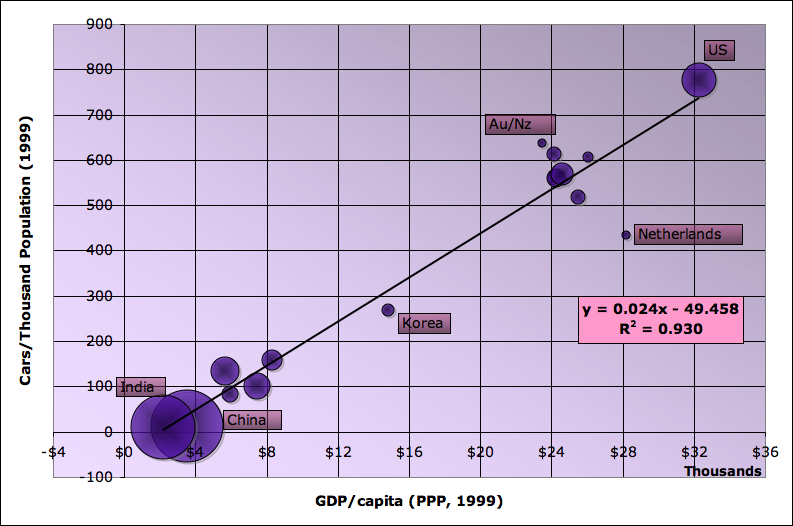

Now, global figures on auto ownership have proven hard to find. The best I've been able to get is some data from the EIA for a small selection of countries, and the world as a whole, for 1990 and 1999. However, it's probably enough. I combined that data with GDP data from the IMF, and UN population data to come up with the following graph:

Cars per thousand population versus GDP/capita for selected countries in 1999 (using 1999 PPP dollars). Bubble area is proportional to population. Sources: Auto ownership from the EIA, GDP data from the IMF, and population data from the UN.

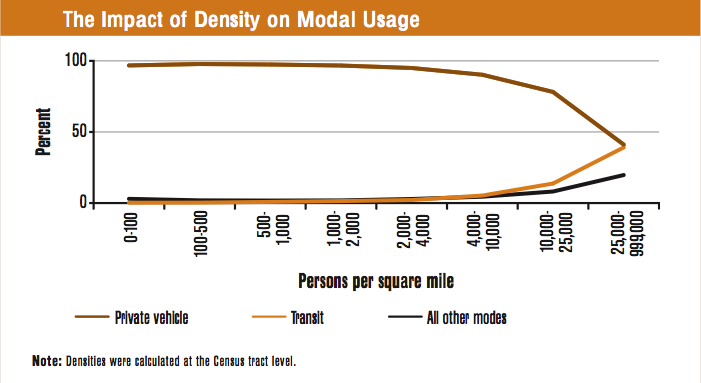

Both travel budgets are of very rough nature only. However, since they apply to virtually all people, independent of income, space, and time, strong regularities in aggregate travel patterns are observed when we compare cross-sectional and longitudinal data of all travel surveys, including those from the developing world. The travel money budget along with country-specific characteristics of the transportation system (land-use, prices, etc.) translates disposable income into daily distance traveled. All other patterns can be largely explained by the travel time budget. Using this approach, travel patterns of countries with very different characteristics at first glance evolve on nearly uniform trajectories. Thus, despite their only rough stability, the travel budgets offer a simple, elegant framework on the basis of which average travel behavior characteristics can be approximated on aggregate levels.While there isn't enough data above to prove this statistically, it rather looks like the major secondary variable controlling car ownership would be population density. The country with the lowest car ownership for their income level is the Netherlands, which is one of the most densely populated countries in the world, and the region with highest car ownership for income level is Australia/New Zealand, which is one of the most sparsely populated parts of the world. This matches the intuition one would get from US data, where public transportation ride share is highly correlated with population density, and auto usage inversely so:

There's a similar pattern in vehicle ownership - households in areas with the highest population density (over 10,000 persons/mile) are much more likely to have no car, and much less likely to have lots of cars:

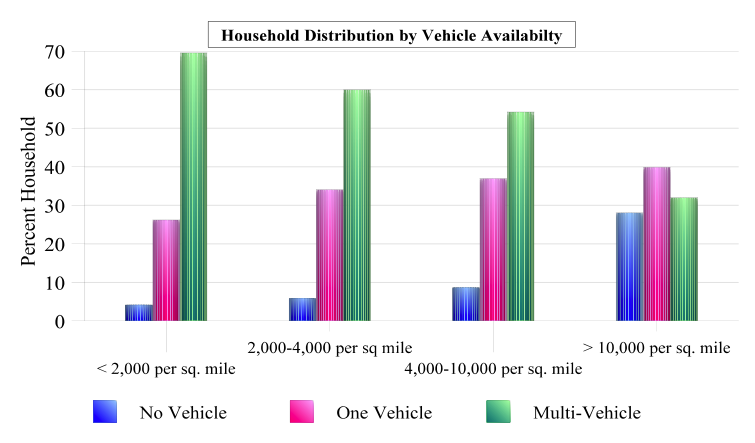

This is somewhat encouraging for keeping the car count down, since the average world citizen in 2050 is likely to live in a very dense city in what we today call the developing countries (a lot of them will be pretty developed by 2050 under my assumptions). However, the discouraging thing is that those countries are growing the fastest economically, and that means rapid growth in car ownership also:

Annual growth rate in cars per thousand population versus annual growth rate in GDP/capita between 1990 and 1999 (using current PPP dollars). Bubble area is proportional to population. Sources: Auto ownership from the EIA, GDP data from the IMF, and population data from the UN.

So let's try to roughly guesstimate the number of cars people might buy if they weren't resource constrained under this scenario, and then look at the resource constraints that might prevent them from having that many cars. I'll do the guesstimation three different ways which should give us a rough sense of the ballpark.

The first method is to note that the $28k/person/yr GDP in 2050 (expressed in 2006 dollars) would be about $23k in 1999 dollars. On the straight line in the ownership versus GDP graph above, that would place us at around the 500 cars/person mark. However, if we figure the average citizen is at Netherlands densities, we might knock 200 cars/person off that total to come out around 300 (give or take). With 9 billion people, that's about 3 billion cars in round numbers.

Another way to get to it is to notice that in the growth rate comparison, the average elasticity is a little more than 1 (ie 1% growth in income/capita leads to 1% growth in car ownership/capita). The EIA says that global car ownership in 1999 was 122 per 1000 people, which was 730 million cars. This source says there were a little less than 1 billion cars in 2006, so let's figure 1 billion in 2007. So car ownership grew 4%/year, and the global economy averaged 4.3% growth over the same period. Close enough to an elasticity of 1. So if we extrapolate that out to 2050, we go from 150 cars/person and $75 trillion today to $350 trillion and thus about 700 cars/person in 2050. If we again knock a couple of hundred off for high density city effects, we would get down to around 500 cars/1000 people, or about 4.5 billion cars. This is effectively to say that another 40 years of economic growth at something like current rates would place the world average roughly at current European levels of car ownership, which sounds reasonable if only we can find some way to power that many cars.

The third method is to use some data from here which show production of autos (rather than ownership). Production from 1997 to 2005 grew at an average rate of 2.43%. If we apply that growth rate to ownership and extrapolate to 2050, we get 2.8 billion vehicles on the road at that time.

So all three methods come out somewhere in the range of a few billion vehicles on the road in 2050. Whether it's 3, 4, or 5 we can't know, but clearly it would take something on the order of a major economic collapse somewhere along the way for there to still only be 1 billion cars on the road then. (For example, Soviet car ownership declined from 357 per thousand people in 1990 to 134 per thousand people in 1999, so that's what a major economic collapse can do). Let's take 4 billion as a reasonable working number, with the understanding that this is ± 25% (at least). Is there any way that many cars could be built and powered? Let's first look at powering them, and then building them.

Running Four Billion Cars

The Tata Nano will sell for about $2500 (US) in the base model, and get about 51 mpg (US). Source: Wikipedia.

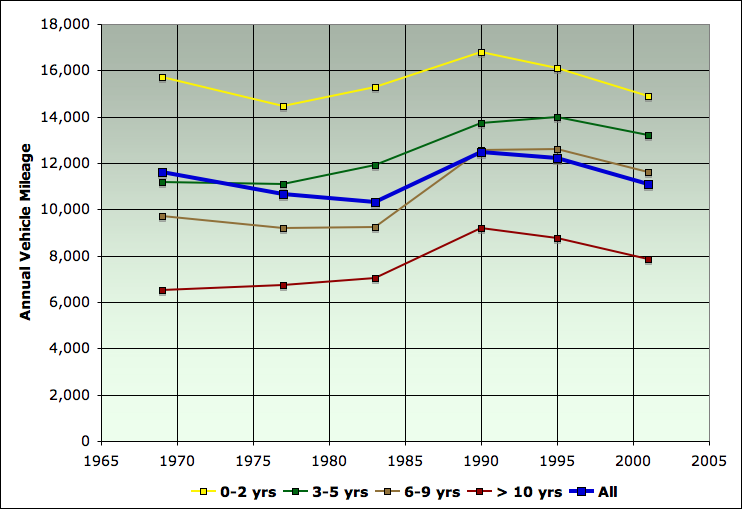

US annual vehicle mileage for vehicles of varying age grades. Source: 2001 NHTS Summary of Travel Trends .

I don't really see doing too much supplementation of this with biofuels. Even the 1mbd of biofuels the world is already producing is causing a lot of problems, and it has the potential to get much worse quickly. Although cellulosic ethanol in theory could help, in reality most of the good agricultural land on the planet is already in use, and expansions onto the remaining land will tend to create far more carbon emissions than they save. (See two recent Science papers by Fargione et al, and Searchinger et al which are pretty convincing on this point).

So to run 4 billion cars, we should be looking at more like an average fleet economy of 200mpg to 250mpg, to keep the fuel bill down around 10mbd. That makes it likely that most of the energy would have to be coming from something other than liquid fuel.

There are two basic possibilities. The first is the hydrogen economy, in which renewable/nuclear power is used to produce hydrogen via electrolysis. The hydrogen is then used to power vehicles (and other things). I'm deeply sceptical about this whole idea. My objections are not primarily technical (though there are technical concerns) but rather based on the market diffusion problems.

Generally, diffusion of a new technology requires that there be early adopters who see value in it, then a larger group of less early adopters who are willing to do it once the worst bugs have been worked out, then the bulk of customers who only convert once the technology is really well established and their friends are starting to do it, and then finally the holdouts who cling to the old way of doing things until it becomes really not viable. This is the mult-stage diffusion process that has to occur.

Hydrogen has the huge problem of requiring a new infrastructure. So there need to be both early adopters on the infrastructure side (investors willing to fund hydrogen pipelines, gas stations owners willing to put in a hydrogen pump, etc), and early adopters on the consumer side (people willing to buy hydrogen cars). And in the early stages, both of these kinds of early adopters are going to have a miserable time because there won't be enough of the other kind close by. (I buy a hydrogen car, but have to drive 100 miles to buy hydrogen, or I open a hydrogen station and I lose my shirt because there are only three hydrogen car owners in my city).

Now, if hydrogen cars were the only way to get around at a decent speed, people would find a way to get over these hurdles (after all, cars succeeded in displacing horses). But hydrogen cars will have the problem that there are already lots of gasoline cars on the road. Gasoline of course is expensive and likely to get more so over time. But hydrogen is even more expensive and, even in my scenario, is not likely to get cheap for decades. In the meantime, a hydrogen car is at a serious disadvantage to a gasoline car. Therefore, they won't get adopted any time soon.

The other story, which I think is a lot more appealing, is that the present trend to hybrid gasoline/electric cars moves onto a plugin-hybrid stage in which the car has a larger battery and motor and gets plugged in to the electric grid at night or during the day at work. This has a far less serious adoption barrier. We already have distribution infrastructures for electricity and liquid fuel, so the only early adopter needed is the buyer of the plug-in hybrid. To the extent the grid needs to get expanded over time due to increased electricity usage by plug-ins, this will be done on the basis of clearly proven demand trends and can be a relatively low-risk decision. The speed of adoption of plugins will essentially be controlled by the relative prices of electricity and liquid fuels (including any carbon emission surcharges and governmental incentives).

In this scenario, power for cars will be predominantly coming from electricity by 2050, which I have already argued could be plentiful if we make the necessary infrastructure investments. So then the issues become whether it might be feasible to build that many plug-in hybrids.

Building Four Billion Plugin Hybrids

I stress of course that I'm not proposing that we make any crash program to build plugins. I'm simply proposing that as the economy grows and people, particularly in developing countries, get wealthier and want more cars, we create incentives to shift the car population gradually to hybrids and then plugin hybrids. Such incentives are already in place in a number of countries (eg the hybrid tax credit in the US). If this is done sufficiently, we would end up with a few billion plugin-ins by 2050. Market forces will do a lot of the work, since electricity is already cheaper per unit energy than liquid fuel, and the gap is likely to widen over time.So then the question is what other resource constraints might we run into along the way, given that energy is not one in my scenario (at least not in the long term). Some things are fairly clearly not problems. The bulk of the car is made from steel, perhaps aluminum in future (lighter), and plastics. Iron and aluminum are the two most common metals in the earth's crust and are unlikely to be serious resource constraints this century. Plastics will be available from oil as long as we can mostly stop burning the oil in automobiles. The necessary roads can be made from concrete, and we are very unlikely to run out of limestone to make the cement, or sand and gravel.

Two issues seem to me to be potentially pressing - lithium for batteries and copper for motor wiring. I will examine lithium in detail now, but defer copper, which is a more general concern, to a future piece. (Roughly speaking, those familiar with the copper issue can imagine that it comes down to an argument about how much copper usage can be substituted by much more plentiful aluminum).

Lithium

The best battery chemistries known for future automobiles all appear to involve lithium. Lithium-based rechargeable batteries have more energy density per unit weight, as well as carrying more energy per unit volume:

Energy density (weight and volume) for various battery technologies. Source: Wikipedia.

The concerns raised in Trouble With Lithium are two-fold. One is that the best and cheapest sources of lithium are limited to a few geographic regions (principally certain high desert regions of South America and Tibet) and that therefore the world would be as vulnerable to political problems with these regions as it is now with oil and the Middle East. The second is that the expansion of lithium mining required to support a plug-in hybrid world would be enormous relative to present day production. There is some validity to both these concerns, but let's first look at the total amount of lithium available, see if that's enough, and then come back to the potential bumps along the way.

The best estimates available are these (expressed as thousands of tonnes of elemental lithium).

| Variable | Quantity (KT Li) |

|---|---|

| Reserves | 6,200 |

| Reserve Base | 13,400 |

| 2005 Production | 21.4 |

| 2006 Production | 23.5 |

| 2007 Production | 25 |

As you can see, there is not an urgent lithium problem - reserves/production is currently about 250. (As far as I know, no-one has raised a serious question about the validity of lithium reserve numbers). However, this is with hardly any cars containing lithium batteries. How does four billion of them change the picture?

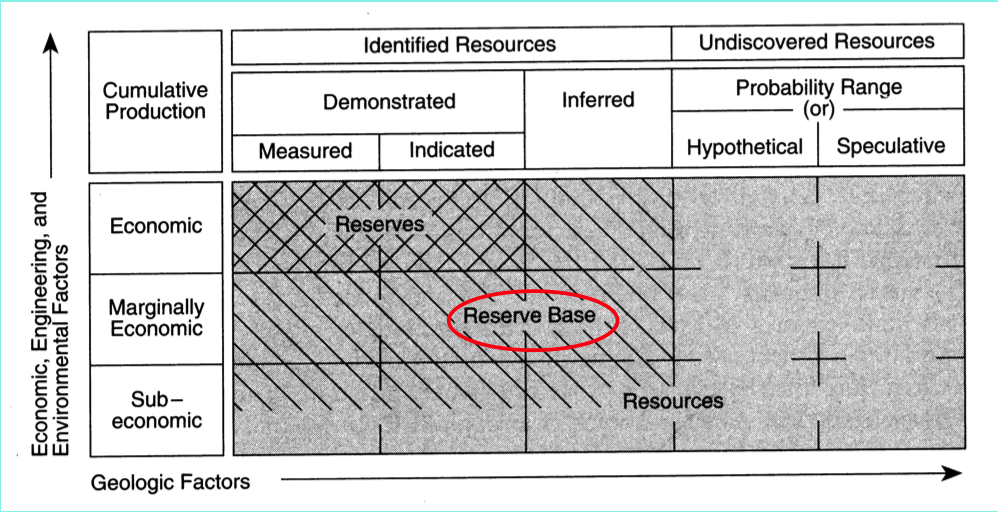

Let's take a moment to look at the definition of reserves and reserve base:

Schematic of various categories of reserves and resources. Source: Resource Limitations on Earth.

Thinking about 2050, it seems to me that the reserve-base is the best guesstimate of how much lithium might be available if really needed (ie if we haven't figured out a better idea in the meantime). This allows for improvements in extraction technology and/or higher prices (manageable by a wealthier society), but we aren't getting out into "lithium from seawater" territory - the "reserve base" is lithium in known deposits.

Furthermore, since cars are 95% recycled even now, it seem reasonable to assume that long before 2050 we can pretty much be recycling all or nearly all of the lithium. So the calculation I'm going to assume (and I freely admit this is just a rough back-of-the-envelope sort of exercise) is to just divide the 13.4 MT of lithium reserve base by the 4 billion cars, which gets us an average of 3.3kg of lithium per car. Now, currently, it takes 0.3kg of lithium to get 1 kWhr of battery capacity, so that 3.3kg of lithium represents about 11 KWhr of electricity storage.

A reasonable assumption is that a plugin would require about 0.2 kWhr/mile. Thus the 11 KwHr average battery is 55 miles of all-electric range, or about 90 km. Now if we assume that they all get charged at night (figuring that the extra charging during the day for some cars is cancelled by others that can't or don't charge at night) then we can basically treat this as the maximum amount of daily mileage that can be covered by electricity, rather than liquid fuel.

Which allows us to make use of this data on the cumulative distribution of daily miles:

Cumulative distribution of personal daily travel distance in the US, UK, and an estimate for developing countries. Source: The Geography of Transport Systems, summarizing data from Regularities in Travel Demand: An International Perspective.

(Obviously, powering even more cars after 2050 would require at some point that we find more lithium, figure out how to extract it from seawater profitably, discover some better battery technology, or somehow otherwise work around the problem. I'm willing to live with this - who knows what 40 years of innovation will come up with. We wouldn't be worried about peak oil if it was 40 years off, and so I'm not going to worry about running out of lithium then -- we have to leave our children something to do...).

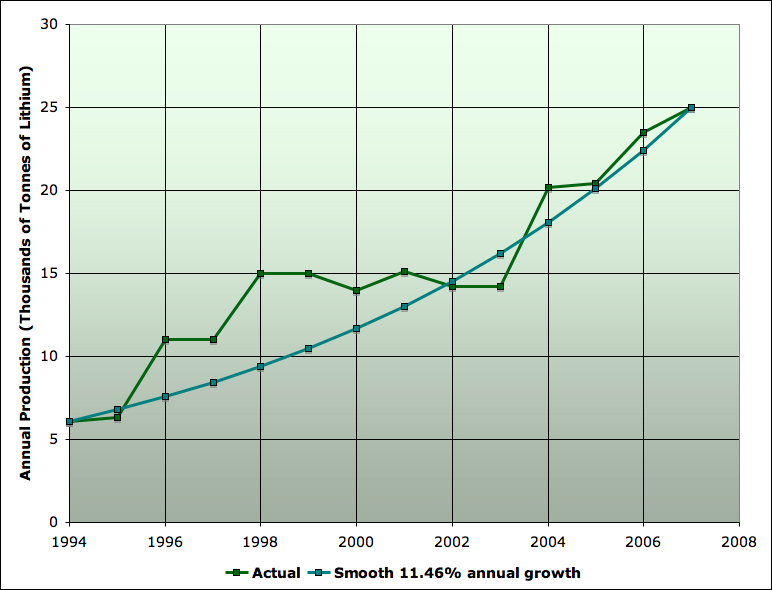

Now, let me go back to the other concerns raised in Trouble with Lithium. The author, William Tahil, spends a lot of time concerned about the disconnect between the current production of lithium and the amount required to turn out all of today's car production with lithium batteries, or convert all of today's cars on the road to lithium. But these are not reasonable models for the time path of lithium/plugin adoption occurring. Instead, the right way to frame the question is to assume that the market for lithium-ion batteries in plugins grows gradually over time, and then look at the required growth rate in lithium production and see if it looks outrageous. In my case, for a first quick calculation, I'm just going to look at what constant growth rate is required to produce a cumulative 13.4MT of lithium by 2050, and then compare that to recent history. Here is the recent history:

Recent history of global lithium production (exclusive of the US). Source: USGS. Note that the USGS doesn't publish US production because there is only a single US producer. The US will not be a major factor in lithium production going forward.

The second major objection Tahil raises is the geographic concentration of lithium that will thus give some countries a lot of leverage over global supplies. He is undoubtedly right, but this will be only one of many such world problems, and far from the most serious. The world is going to be ever more dependent on the Middle East for oil in coming decades. The world will be critically dependent on Asia for a lot of manufactured goods. Asia and the Middle East will be critically dependent on big food exporters like the US and Brazll to eat. If we don't trade, we are all going to be in a world of hurt. In this context, concentration of lithium exports doesn't seem like the worst problem (at least if lithium exports stop, it only hurts the ability to build new cars, not run the existing ones).

In conclusion, these stylized facts seem to be roughly true:

- With the existing known reserve base of 13.4 million tonnes of lithium and less than 10 mbd of oil, we could run 4 billion cars in 2050.

- If we assume most residents of the planet are living in dense cities in the third world with degrees of public transportation comparable to dense western cities today, then 3-5 billion cars should be enough to satisfy people's aspiration for automobile transport by that time.

In the next 5 years we'll face a completely different problem: how to mass produce 4 billion components for renewable energy systems. This is because in that time the Arctic summer sea ice will disappear, with incalculable consequences for the weather and climate of the Northern hemisphere, including the destiny of the Greenland ice sheet to which Stuart has alerted us 2-3 years ago.

Causes of Changes in Arctic Sea Ice; by Wieslaw Maslowski (Naval Postgraduate School)

http://www.ametsoc.org/atmospolicy/documents/May032006_Dr.WieslawMaslows...

In the meantime, NASA climatologist James Hansen is moving the goal posts from 450 ppm CO2 to 350 ppm as the threshold for dangerous climate change.

http://www.columbia.edu/~jeh1/RoyalCollPhyscns_Jan08.pdf

So what should be discussed here is how we can re-tool all those car plants which will inevitably close down as a result of peak oil, into manufacturing plants of wind generators, solar panels, solar water heaters etc.

We should also discuss what needs to be done to get all that CO2 out of the atmosphere again because we are now already above 383 ppm. Time is now critical. For 50 years planet Earth is out of energy balance with space. We see now increased heat exchange between the equator and the poles.

4 bn cars is the last thing we need. A planning horizon up to 2050 is completely academic. We can consider ourselves lucky if we have good plans for the next 10 years. For the Australian context I have calculated that - if we want all essential transports sustaining our present life (food, basic consumer products etc.) and all traffic in rural areas to continue at present levels capital city motorists will have only 1/5th of current fuel supplies by 2020 (assume 30% reduction of oil supplies according to the EWG report). By that time, therefore, long distance commuting in urban areas by private car will be history. Mandatory car pooling will help while we build up electric urban rail on all freeways as has been done in Perth.

http://www.sustainability.dpc.wa.gov.au/CaseStudies/trains/trains.htm

I am sorry to say this very clearly: our unrealistic car dreams will kill this planet.

matt, i agree with you. the next 5-10 years will be critical. but i believe it's wrong to assume that we will convert the factories by assuming the current economic situation. most likely, they will postpone the investments, and only in the final hour will we rush to a green frenzy. but by that time, most of the money that could be used to get a head start will be used for building smaller (petrol) cars, hybrids, biofuels, and so on. When the governments will realize that they need rail, there will be little money to do the task in a big way, because much of the income will be lost due to the citizen's eroded buying power and increased government costs.

long story short, i believe we'll just keep digging deeper hoping for some miracle, and one day we'll realize it takes a tremendous effort to climb back up. we're not "hoping for the best, preparing for the worst". we're just hoping for the best and expecting for it to happen.

All this effort to move around when we could be building places that have almost everything we needed within walking distance.

I call it the transportation illusion: the illusion that solving the problem of how you get to the people and things you need is more important than solving the problem of how to ensure that the people and things that you need are already living and existing where you are.

Matt,

Chris Vernon circulated this latest offering from Hansen a couple of weeks ago - its the same you have but with the voice over. I gotta say I thought this was off the bad end of the scale and not worth the time of day.

https://admin.emea.acrobat.com/_a45839050/p89418435/

You make an astute observation:

So would you care to say which of the laws of physics have changed to cause such a dramatic revision of this theory. Or is that Hansen and colleagues have just been plain wrong in their understanding of the natural world? So if they were wrong then why should anyone believe them to be right now?

The latest temperature anomaly map from GISS is indeed worrying:

All that anomalous warm in the arctic region. And all that anomalous cold in central Asia, Africa, Greenland, The Pacific and Antarctica. We need to remember that these maps compare today with the mean datum period of 1951 to 1980. There is absolutely no reason to believe that this datum period is normal.

If Hansen is right you may as well kiss your ass goodbye - cos we're already passed 350 ppm and heading north at break neck speed. There is nothing on this earth going to stop China, India, the ME and others having a C based binge - that is until FF run out - the peak year is 2020.

I share your concern about the loss of Arctic sea ice and I also share your concern about the additional forcing caused by CO2 and other GHGs. The main worry here is that no one seems to understand the consequences of these phenomena on Earth's climate. The sighting of a blue parrot in a Norwegian Fjord I dare say will send panic through the international GW community.

4 Billion electric cars are of course part of the remedy - of reducing uncertainty about what we are doing.

"If Hansen is right you may as well kiss your ass goodbye"

Been there, done that.

I think concerning ourselves with how to build so many cars is a total distraction.

Please don't be so dismissive with comments like "which of the laws of physics has changed." It helps to understand the social context in which climate change science occurs (much like the denial around peak oil), and to understand how the the dynamics of ice sheet collapse have been misrepresented by models.

Please read:

www.climatecodered.net

I basically concur with Climate Code Red: In a few years we either go into an "emergency mode" and dispel with "normalcy" to deal with the problem or we let that window slip away and be faced with the existential crisis of being alive for a short while as it all goes to hell.

Jason, it wasn't like this in Nansen's day - too much f*ing ice back then:

The first voyage of Fram proved that the Arctic Ice pack rolls on a conveyor belt of ocean currents and is renewed every 3 to 4 years? So when I hear folks talking about irreversible loss of Arctic Sea ice I really gotta laugh out loud. Do you think the IPCC are aware of this?

Climatecodered does reference the fact that ocean currents have warmed the water the Arctic ice pack sits on. So this comes back to the critical question:

Is our climate controlled to a large extent by ocean currents or is it vice versa? Off course there is a bit of both - but I always learned the former to be dominant.

Any physical scientist who has been out in Alpine snow conditions in Spring is aware of the power of albedo in melting snow - as a patch of soil expands exponentially in spring sunshine - at the expense of snow pack. If the IPCC and Hansen et al have failed to model this correctly it leaves me with a feeling of dismay.

So what exactly is the evidence that anrthopogenic climate forcing is the cause of the current decline in Arctic Sea Ice summer minima?

http://www.fram.museum.no/en/

Trends in perennial sea ice extent:

Source: Nghiem et al., Rapid reduction of Arctic perennial sea ice

And the pattern of arctic ice circulation:

Note gyre in center. Source: NSIDC.

Yes, NSIDC shows it best.

http://www.nsidc.org/news/press/2007_seaiceminimum/20070810_index.html

Animated table 4 on the above link is showing constantly moving, thickening and thinning sea ice. It was once in color, now in less informative B/W. Can someone follow up on this to change it back to what it was?

Just now it displayed in color for me. It did seem like a slow server but worth the wait. Thanks.

Thanks for the charts Stuart - I learn something every day. The general idea of water flowing in through the Bering straights and out through Baffin straights and E Greenland holds though. And the water coming in the top is warm.

The main point I wanted to make here is that the Arctic Sea Ice is on average very young - a handful of years old - and is renewed on an "annual" basis. Its not like the Greenland and E Antarctic ice sheets which have taken hundreds of thousands of years to millions of years to form. If we lose these then I'm prepared to accept that they are lost "forever" to all intents and purposes for Homo Sapiens. All we need is one (or a series of 2 or 3) really cold Arctic winter to restore the Arctic Sea Ice to its former glory in terms of volume. Whether or not that happens soon is another issue.

Your first chart showing perennial sea ice extent is extremely interesting. Would you agree that the 1957 to 1971 we have some form plateau and that the current trend of accelerating loss began in 1972? 1972 looks like a really dramatic year in the Arctic. What happened?

To my eye what we are experiencing now, started then. So is this anthropogenic GW or is it something else? My chart up the thread has 126,053 million tonnes oil equivalent (mmtoe) burned 1900 to 1972 and 251,166 mmtoe burned 1973 to 2007. So we have burned more than twice as much in the last 34 years than in the preceding 72 years.

If the onset of Arctic Sea ice loss in 1972 was due to human activity then we are well and truly screwed. The thermal and kinetic inertia of the ocean atmosphere system will ensure on-going highly unpredictable climate change for decades - and there is absolutely nothing man kind will be able to do to prevent this. At best we can mitigate effects by building coastal defenses and prepare to cultivate Greenland - like the Vikings did 1000 years ago!!

If on the other hand the onset of sea ice loss in 1972 is due to a natural cycle then is it not the case that what we are experiencing now is a continuation of that same cycle that has presumably happened many times before? And Planet Earth and all its species survived.

Where my position differs I believe from your own and certainly from the GW advocates is that I am uncertain which of these options is true. I actually lean quite strongly towards the latter - that is perhaps down to denial - but also down to the fact that we know The Vikings cultivated Greenland as I already mentioned. I would see some danger that anthropogenic GW may amplify the natural cycle - unquantifiable and unstopable.

If it is the case that we have jumped off a GW cliff then we had best prepare our parachute. Flapping around hysterically trying to regain the cliff edge just ain't going to get us anywhere. If we have jumped we can't go back.

Euan,

it's all a matter of rate of change (as is so often the case!).

If warming comes too quickly, we are toast.

If it comes slowly, we can adapt. We human beings could possibly adapt even to quicker climate change, but nature can't. In former times, when there was climate change, it usually took hundreds to thousands of years to manifest itself.

This time, the exploding CO2 emissions could do it really fast - too fast for slugs, bugs and cheetas.

Cheers,

Davidyson

Davidyson - I should know more about past mass extinctions, but don't, other than they probably were not instantaneous.

Are there any examples to date of species lost to global warming? This is a straight question - I don't know the answer.

I am aware that we are losing vast numbers of species from rain forests and other habitats - and this is a true and avoidable tragedy. It brings us back to what I believe we need to focus on which is population reduction some how - and that of course will ultimately lead to lower CO2 emissions.

I'm also aware that fish stocks are moving around as are birds and insects in response to the rapid warming we have experienced this past 20 years or so. The structure of food webs and ecosystems are changing - as they always have done so. But are species getting wiped out?

Indonesia provides a very interesting case history where vast tracts of rain forest have been burned to grow bio fuels - and this has been in response to declining oil production in Indonesia.

Euan

The American Pika is thought to be headed for extinction. They live at altitude and can die if the temperature goes over 23o C for an hour. The species extinction rate is about 50,000/yr. Presumably some of these lost their last members as a result of climate change but many other human activities, particularly related to land use and fishing lead to this high rate. The normal rate is about 50 to 500/yr. http://news.minnesota.publicradio.org/features/2005/01/31_olsond_biodive...

Other species considered affected by climate change are the Polar Bear, Moose, Florida Panther, Canada Lynx, Brook Trout, Salmon, Mallard Duck, American Gold Finch, Sage Grouse and Coral.

http://www.usatoday.com/weather/climate/2006-05-30-critters-warming_x.htm

Chris

"The main point I wanted to make here is that the Arctic Sea Ice is on average very young - a handful of years old - and is renewed on an "annual" basis. Its not like the Greenland and E Antarctic ice sheets which have taken hundreds of thousands of years to millions of years to form".

Oh, certainly. But still, there is a distinction between the stuff that's five or ten years old, and thinner ice. Once the perrenial ice is gone, it's harder to recreate it because the thin stuff melts faster every summer and lets more heat into the ocean.

The reason why it's probably irreversible are heat stored in the ocean, and basic physics suggesting that global temperature can only go up from here (bumpily but basically up). The reason people think this is almost certainly due to anthropogenic GW is because climate models pretty much all predict a much warmer Arctic, and lo and behold we have a much warmer Arctic (albeit that the sea ice melt is going much faster than they predicted). The climate models are fairly well able to explain the 20th century temperature history by now, and able to distinguish natural variability from forcing in general. However, it's certainly possible that some kind of natural fluctuation is accelerating the anthropogenic trend here. I suggest reading something like this GISS E paper (PDF) on the model data fit. Incidentally, I think you'll regret criticizing Hansen in public like this - he really is first rate, and I don't think you've done the spadework yet to understand the issues, let alone be criticizing leading thinkers on it.

Here's a speculation: it almost appears that climatologists are much better at modeling the atmosphere than they are at modeling the ocean, and better at the ocean than the cryosphere. Would that seem accurate to others?

Stuart said:

Which seems a shame considering the oceans are so important, and is one of the reasons why it seems to me to be premature to be too certain of the future course of events, although the probabilities are clear.

The Navy has been running subs under the Arctic for decades. Turns out Arctic sea ice loss is about 80% so far when thickness and not just extent is calculated.

Hansen has also proposed was to geoengineer a refreezing of the Arctic using injected atmospheric sulfates. The ice cover can be rebuilt quickly, which is important because if the Arctic opens up then Greenland could go quickly, which would then mean the loss of W. Antarctica and a runaway greenhouse effect from permafrost melt, etc. This could quickly lead to Lovelock's nightmare scenario, which I dismissed when it initially came out but the more I learn the more I am afraid he looks right.

While the Arctic is being artificially kept cold to buy us time the global economy needs to decarbonize over a 10-20 year period and carbon needs to be sequestered in soils and vegetation regrowth to bring us down to 300-320 ppm.

Forget about 450 ppm and peak fossil fuels saving us. I was giving talks while at UC Davis about peak fossil fuels making the SRES reports grossly wrong about emissions potentials, but at the same time the slow feedbacks of the climate system could take a 1-2 C initial warming into a positive feedback loop that gets out of hand. I never imagined it would happen so soon.

Jason - I gotta say I can at least respect your position on this. It is unequivocal. 300 - 320 ppm takes us almost back to pre-industrial concentrations and this tallies with my observation that the current cycle of sea ice loss (area) appears to have begun in 1970 when concentrations were about 325 ppm. I dare say volume losses will have started many decades before

And so what your saying is the time for 1/10th measures let alone half measures is over and we need to try and refreeze the Arctic, virtually shut down combustion of FF and take drastic measures to reduce atmospheric CO2 form its current levels.

And so if your are right in your analysis of our situation I can respect this point of view. I must add that I sincerely hope that you are very wrong because you are aware that none of this is going to happen and proposing it will be seen as bat shit crazy by 90% of people on Earth - until they are gasping their last gasp in a parched (or drowned) land scape.

What I cannot respect then are those who hope half or 1/10th measures might work. If you lack total commitment then you are as well doing nothing at all.

So I conclude by repeating I hope you are wrong and I hope Hansen is wrong. I certainly lack the commitment to do what you would ask - if for no other reason that I find it very difficult to believe that 30 to 40 ppm above the historic baseline will be lethal for our climate - and the target for reductions seems to be shifting on a daily basis. And there seems to be so much of the climate - ocean - ice system that is still very poorly understood.

Euan,

Where I grew up, the only war memorial was a civil war memorial. Names from other wars have been added to it but a single statue of a soldier surrounded by four green cannons is the marker.

In 1783, a petition was brought to parlimement to abolish slavery in England. Quakers were also organizing in Philadelphia in 1775. Between 1861 and 1865 12% of the US population was freed from slavery and much of its real and paper wealth evaporated. That is about 90 years between conception that there was a problem and putting an end to the problem.

In 1903, Teddy Roosevelt established the first National Bird Preserve and in 1970 we had the first Earth Day. Slavery was abolished in England 50 years after the first petition. Environmentalism is a little slower. In 2006, the USGP called for an 80% cut in CO2 emissions within a decade (your bat shit crazy kind of thing). The GOP was established in 1854, seven years before the start of the Civil War. What is a little different is that no one running for president now thinks global warming is not a problem.

The US seems to go through spasms of about four years durations from time to time to fulfill a commitment to freedom that has built up over a period of 90 or so years. The transformation of industry in the 1940's, the emancipation of the slaves in the 1860's, Civil Rights in the 1960's, the Great Awakening of the 1730's or the Revolutionary War of the 1770's were all culminations of themes of freedom that had been brewing for generations. I think that global warming, or giving due consideration to the ecosystem, can be seen as a freedom issue. In deep ecology, it is a matter of respect for all life while in human terms it can be seen as securing the blessings of liberty to our posterity. This was one of four reasons given for establishing the Constitution so you could kind of say that it is part of our mission statement.

I would thus not be too surprised to see about four years of enourmous activity starting within a decade that leaves the US and the world quite transformed with global warming looking like it is well on the way to solution. That the challenge appears to be growing greater as we learn more about the situation is probably not something to worry about. It will only spur us to greater effort I think. Interesting times....

Chris

Chris - thanks for all your input here. But I remain skeptical. I accept that GHGs will lead to warming and climate change superimposed upon the natural cycle of the Earth. Warming superimposed a cooling phase may lead to stability and warming superimposed upon a warming phase may lead us into new and worrying territory.

I just read the link on Arctic Ocean currents posted by Matt:

http://www.ametsoc.org/atmospolicy/documents/May032006_Dr.WieslawMaslows...

It basically shows what I was trying to say - that warm water flowing in through the Bearing straights may account for 50+% of the recent sea ice loss. Now it is predictable that the GW crowd will jump up and down claiming this is further evidence of GW. I'd tend to want to know more about longer term ocean circulation cycles. You just need to look at a map of ice loss - and you see it is concentrated around the Bearing entry point.

Incidentally, the Maslowski presentation has charts of ice area, thickness and volume that present a totally different picture to that presented by Stuart with a sudden onset of change in 1997.

Looking at the moving target for CO2:

Kyoto about 350 ppm

Hansen initial target 350 ppm - but aiming at 300 to 350 ppm

Jason Bradford - 300 to 320 ppm

I'm afraid i just don't think there is a chance of meeting any of those. In fact I think the most likely out come is that CO2 marches up towards 450 ppm and will only start to decline when FF peaks - around 2020.

The difficulty in turning around the atmosphere is best illustrated by looking at the CFCs - hailed as a great success. Much easier to tackle - and yet stabalisation / small reduction is all that has been achieved to date. A major triumph yes. The methane chart here is interesting - not much sign of runaway melting of clathrates here. I wonder if this is pipeline repairs in Russia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Major_greenhouse_gas_trends.png

I remain concerned that a significant portion of what we see in the Arctic today has nothing to do with Man. We can sit back and hope that there is a corrective mechanism that is currently unknown - one of very many unknowns. If there is not, and Greenland begins to melt in earnest then we may well see a panic set in among global leaders - but then it will likely be too late.

You mentioned investment and IPCC scenarios down the thread. The big stumbling block here is the need to spend a fortune now to maybe prevent a catastrophe that might happen, as opposed to waiting to see if the catastrophe happens and then spending the money to mitigate the consequences when you know for sure what and where the problem lies.

Euan

Maybe relevant research paper linked at climate ark on historical flows of water into Arctic (15 million years):

http://www.earthtimes.org/articles/show/186402,german-scientists-warn-of...

Galactic - curiously i spent the greater part of my professional career analysing sediments for Nd isotopes (oil reservoir rocks). We also just had a long email exchange about looking at Arctic ocean floor sediments - I'b be particularly interested in paleo ecology indicators that might indicate the presence or absence of sea ice for the last 10,000 to 1,000,000 years. This I believe will become one of the biggest questions this decade.

The paper you reference i fear may have the cart before the horse - concluding that the disappearance of sea ice has caused ocean currents to change and not vice versa!

Euan,

I think you need to separate the emissions reductions from the response of the atmosphere which takes longer. The CFC emissions have been cut dramatically and the effect is now showing in the atmospheric abundance in your chart. The residence time of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is longer than for CFCs so emission cuts lead to stabilization rather than the reduction you see in the chart. In order to reduce the concentration of carbon dioxide, we need to remove it from the atmosphere. It turns out that this is fairly easy to do in the sense that removing carbon dioxide can multiply loaves and, possibly, fishes. Cutting emissions also looks as though it can be done in a way that makes energy less expensive.

In each of the American upheavals over freedom, prosperity has increased as a result. This was not the intention of those movements. My working hypothesis is that moves to increase freedom tend to broaden the pool of creative inputs. Buckminster Fuller points out that when the war to end fascism came to a close, automation had grown so much in four years that there wasn't any work for the demobilized soldiers. So, everyone when to college and this resulted in a huge rise in prosperity. Perhaps doing the right thing puts people in the mood to do more of it.

It is worth remembering that in the lead up to that war there were leading Americans like Senator Bush who greatly admired Germany and sought to assist its efforts. There are many now who feel that fossil fuels are worth fighting over. Perhaps oil depletion helps get past this kind of thinking since it is becoming clearer that we are going to have to make do without fossil fuels sometime while global warming sends us in a particularly productive direction. Regardless, it does feel as though things are coming to a head.

So, seeing the result of cuts in CFC emissions in the atmosphere is encouraging. It shows that we know what we are talking about. But, we also know that to reduce the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere will require efforts to remove it. This is an enormous challenge in scale and perhaps just the thing to cure the ennui that leads to such products of idleness as mortgage backed securities.

Chris

I agree completely about the urgency of the climate issue.

Your chance of selling the planet's population on a no-car, no-plane future are zero. Nada. Not going to happen. If that's the alternative, people will decide it's hopeless and take their chances on adapting to climate change. This kind of proposal is irrelevant at best and actively counterproductive at worst, in my opinion - allowing the perfect to be enemy of the good enough.

We need to propose something that can meet (most of) people's aspirations.

We need to propose something that has a prayer of working. The fact that a global supergrid and stock market growth until the end of the century can be 'sold' to gullible people does not mean that they sensible proposals. If physical reality and peoples aspirations are in conflict, guess who is going to win.

"People's aspirations"?

Really. A century ago who "aspired" to own a car? Car ownership is human nature? Because advertising con men have sold us a load of BS we are now all doomed?

You are right RK physical reality always wins.

And while the gang here at TOD spins pipe dreams some of them should figure out that social reality is constructed by us and could be rearranged by us.

Not that I expect that to happen

I think one could argue that there is a strong aspiration towards personal transportation, whatever is available at the time. Once individual wealth reaches the necessary level, a sizable fraction of people look to become independent of public transportation, with its schedules and/or sometimes limited availability. Technology and cheap fossil fuels have (temporarily, at least) greatly lowered the threshold for the amount of wealth needed to reach that point.

Whatever is, is the only way things can be. And we will create the tech and make the investments to make sure it stays that way.

Devise circular arguments and submit to Fate.

I'm not worried about 4,000,000,000 cars ever happening, I'm worried about the utter death of imagination.

Dunno bout dat, when I lived in the Big Apple I didn't own a car, got to work on time almost every day and I wasn't even poor. I personally knew well to do people who took the subway just like I did. Some of them were in advertising creating ads to sell cars, they laughed all the way to the bank.

I aspire to anti-gravity flying vehicles and space-timewarp travel to other planets and suspended animation and eventually uploding myself to the galactic wide web and living forever! Please can't I have my fantasy for just a little while longer? None of these things are dependent on fossil fuel - I promise. Not in my fantasy anyway.

So you need to identify which parts of what I'm proposing, specifically, are physically impossible (with numbers).

Yes, the supergrid is far fetched but we do have plenty of fission fuel. And it is pretty clear that we could build a primarily nuclear based grid fast enough to satisfy Stuart's model. It just might not happen the way he hopes.

You don't need a supergrid for nuclear, as you can put them where they are needed.

You don't really need one for renewables either, as long as you use them where they are most appropriate, fro instance solar in the South of the US, but not trying to power the North by that means- all you need then is overnight storage.

Limited extensions of the grid for wind would help to reduce variability.

It was clear from Stuart's earlier article on energy that costs are greatly reduced if you allow some nuclear energy in the mix, and alternatives would be very expensive, if indeed they can be done, as they relied on continued massive improvements in the costs of solar energy at the same rate as has happened in recent years - personally I feel that this rate of increase will level off to some degree before long, as maintenance and installation becomes a larger part of total cost, but solar should be good to provide at minimum peak load capacity and probably almost all capacity in sunny areas.

I prefer however to base proposals on what we can be sure we can do - we know that we can power society with nuclear energy,and only modest engineering development is required to get better burn of fuel and so on - we have thousands of operating years of experience, and one whole society, France already gets most of it's electricity from nuclear power.

If solar turns out to be economical I would be all over it though! - that is not going to happen without major breakthroughs for the cold and wintry north though.

I'm all for going in stages. The important thing now is to provide subsidies/mandates to ramp up solar/wind as fast as possible purely on a fuel displacement basis, while permitting nuclear plants wherever they can overcome local political opposition, and fighting coal plants tooth and nail. Fund R&D into anything and everything that even vaguely makes sense. Actual development of a super-grid can happen in stages - more continent grid structure to begin with, and then as the solar and wind costs continue to fall and we want to drive the penetration higher than intermittency will allow without wider averaging, more grid elements can be added.

I think care needs to be taken in providing subsidies for renewables.Feed-in tariffs and mandates can grossly distort the market and lead to missalocation of resources.

In my view the correct and most neutral way of doing things is by a carbon tax

Here in the UK conservation efforts have been pathetic or non-existent.

By putting money into that we get a lot more 'bang for the buck' in terms of carbon reduction than by building power sources.

Things are different in America, but here in Europe mandates and huge feed-in tariffs have lead to a lot of capacity and vast expense on wind power where the wind don't blow and solar power where the sun don't shine.

According to Deutsche Welle 30c/kwh and high taxes are leading a lot of the public to loose interest in efforts to mitigate carbon emissions.

They are leaders in conservation, but their efforts to generate power from wind where it isn't windy and solar at their latitude bemuse me.

Recent Government plans in the UK to develop 33GW nameplate of off-shore wind, actual hourly output of around 10-11GW from Government figures would cost around £40bn.

For the same money you could buy around 14 of the 1.6GW, some 1.44GW actual hourly output of Areva like that being built in Finland, allowing an additional $2bn on top of the present $4bn , total $6bn, £3bn pounds per reactor.

That is about 20GW of power to the grid, all of UK baseload. fuel costs in nuclear power are a minor part of the cost, and life expectancy of the plants is around 60 years, as opposed to 25 years for wind.

It should be noted though that in the UK wind power has excellent load-following characteristics.

Just the same it is clear that a conservation program in the interim before a nuclear build program would lead to much greater overall reductions in CO2 emissions, and more value per pound spent.

Current EU regulations though mean that the wind resource counts towards renewable targets, whilst a nuclear build or conservation don't.

This wouldn't matter if resources were infinite, but they are far from that- personally my guess as to what will actually happen is that some wind power will be built, but nothing like target as it just gets too pricey, and money which could have been used much more effectively will have been wasted.

None of this should be taken as a knock on wind in general, and it is clear that in the US, for instance, there is a lot of potential for on-shore wind power, and China with it's low costs has even better prospects.

As for opposition to nuclear power, a lot of moderate people are coming, however reluctantly, to support nuclear power in order to reduce CO2, whilst a lot more are still bamboozled by false claims of how much we can do with renewables at the moment.

In an engineering sense at any reasonable cost what we can now is conserve, and use our thousands of operating years in nuclear to build that up, with modest engineering advances in fuel burn and so on.

Wind also has a big part to play in many areas, and hopefully solar in suitable regions, and this is the realistic perspective.

The 'no nuclear whatever the cost' brigade - in economic terms or to the environment in CO2 emissions - will doubtless plan to stamp their feet, and scream and scream and scream until they're sick but my guess is that as a political force in the UK at least they will be finished as soon as the first power cut hits, which is probably not long given the dire state of power planning here.

Here is a costed perspective on conservation:

http://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/publications/Investing_Energy_Productivity/i...

Global warming aside, a lot of folk such as the Chinese are likely to take a close look at this as difficulties and the expense of supplies bite - for that country it would make an immense difference in purely economic terms.

I would put a lot of emphasis on conservation - expenditure there can build in cost savings.

With minor refurbishment and rebuilds, wind turbines should easily be kept operational for a hundred years.

And then with major rebuilds, should be as good as new.

Steel does not fatigue that fast, and there is no radioactive waste.

I hope that is so, but do you have data on that?

Certainly the wind companies only specify around 20-25 years, and due to sudden changes in wind speeds stresses are high. I believe in some instances they have even affected the foundations.

The sea is also a very challenging environment, and salt water does not much agree with much engineering.

I would have thought that experience in the North sea on oil rigs would have lead to relatively close estimates of life expectancy from the companies concerned, although I accept that rebuild would cost a lot less than the first build.

Maintenance costs on the nuclear alternative would not be cheap either, so I am not attempting special pleading.

And, in the USA, spend $135 billion to $175 billion on "on-the-shelf" Urban Rail projects that can start physical construction in 12 to 36 months

http://www.lightrailnow.org/features/f_lrt_2007-04a.htm

And start electrifying our freight railroads.

Best Hopes,

Alan

France already gets most of it's electricity from nuclear power.

Yes and no.

There is an irreducible 10% FF in French power generation (even with 10% hydro, which also helps meet peak demand).

All night long, France sells power to it's neighbors at very low prices, to displace their hydro (Swiss), FF (most of them) or fill their pumped storage (Luxembourg) and often buys back peak power at premium prices.

In isolation, modern nuke cannot supply much more than 50% to 60% of the power (without pumped storage).

Nuclear would also benefit from a super-grid. Texas nukes could sell power to Florida at dawn there and to Phoenix & So. CA after 10 PM CST, and pumped storage in the Rockies, Ozarks or Smokies late at night.

Best Hopes for HV DC transmission,

Alan

I can't really understand where you get the idea that there is an irreducible minimum of 10% of FF needed for nuclear, Alan.

At the moment it is not worth doing away with it financially, and energy storage is an issue, but if we do indeed turn to plug-in hybrids you have a built in energy store so you could run the nuclear plants all the time.

So prospectively at least it does not seem that it is irreducible.

And your idea of pumped storage would also reduce the irreducible! :-)

http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/cabs/France/Electricity.html

After the last four N4 nukes were built in France, the nuke building industry in France (large & influential) wanted to build more, but France had "too many nukes", despite the continued FF use.

The lack of expansion created a disruptive dead time between 1999 & 2003 (the last two French nukes completed) and 2007 (start) and 2012 when the first EPR is scheduled to be finished. Construction personnel were idled and found other employment during this idleness.

If a 5th and 6th N4 reactor could have displaced the carbon emissions (and imported fuel costs), they would surely (IMHO) have been built.

I also found out that

Alan

It seems it all depends on what is meant by 'irreducible' - I would go for impractical in this case, and at this time.

When someone asks 'why' the answer is usually 'money' and that seems to be the case here.

They are part of a wider grid and can easily get power form fossil fuel as needed, and pumped storage would presumably have been more expensive.

Overall though, if they had really wanted to they would have been able to do so at a relatively minor cost, as they have around 50 reactors do building another 2 would at most cost 1/25th more.

The impact on the bottom line would be much greater though, and it is not surprising that they chose not to.

A large fleet of electric cars would surely alter the equation though as they would mostly be charged overnight off-peak, as would rising fossil fuel prices or insecurity of supply.

Not sure I agree with that. An article on TOD some months back about new battery technology suggested that the ones in question (LiFe) could be charged in 5-10 minute with really high amperage. I think this would lead to a whole network of immediate charging stations just like today's gas stations. This has significant consequences for the architecture of the grid.

Nobody has cheap gasoline in their garage.

OTOH, most people could charge their car at home much more cheaply and quickly than at a "gas" station.

You are really killing me. I might as well weep, accept the loss of the whole planet then. Cause what you are saying is we should just give in to our perceived need/greed and not ask for anything other than the destruction of most life forms, Gods creation in some belief systems, instead of telling people the truth and asking for some self sacrifice for long-term survival.

If you want a 4 billion car future, run the numbers on how that gets us down to 320 ppm.

If you can't show that it can be done, than your proposal is most counter-productive and irrelevant because there won't be many people around by 2050. Your proposal seems to guarantee die-off, which is what you claim to want to avoid!

Everyone wants to be rich. That's not possible. So everyone is disappointed. Nothing about your plan is going to change that, so why even bother? I don't believe in "evil" in the spiritual sense, but a continuation of business as usual "lite" is about as close as it gets.

And I never said anything about a "no car future" or "perfection." I am much more nuanced and complex than that and so is Climate Code Red.

No way. We are so close to peak fossil fuels that there is really not anything we can do to avoid going to about 450 ppm but there is also not enough fossil fuel to go beyond that.

Stuart's scenario does not have a net carbon impact. It does not increase the amount of fossil fuel that will be consumed over the best case scenario. Other than possibly leaving perhaps 20% of the coal in the ground, consumption of all fossil fuels will peak in 10-15 year and then follow the same trend down no matter what we do.

The fact is that there are plentiful supplies of nuclear, wind and solar and none of these has to have serious negative environmental effects on the world. Once people realize this, life will go on. We will build a new energy infrastructure, a new fleet of vehicles. The world will grow and people on average will grow richer, as they have for the last hundreds of years. This is not evil.

People are inventive and ambitious. We find ways to make our lives better. Fossil fuels have been a blessing and a curse. They have cause tremendous growth of cities and population and are causing a climate crisis. I hope they will run out in time to prevent a major climate disaster. The climate crisis is largely out of our hands. But the end of fossil fuels does not have to mean the end of development and the reversion of society to some more primitive state. There would be no moral good in that.

I don't see that morality has anything to do with it. A supply crunch possibly coming in 2012:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/07/09/AR200707...

Is likely to reverse economic growth. Mr. Staniford appears to be leaving any cost analysis for a future article, but as he himself states a lot of the scenarios he is suggesting will depend on economic growth:

Is this likely ? The same thing worries me for Nuclear power. The cost is so prohibitive the British government wants to leave it all to private investors. How much of that nuclear infrastructure is likely to be in place before we start to see an "oil supply crunch" ? Relocalizing food distribution chains would appear to be a far more realistic solution in the short term.

I am not sure where you got the idea that the cost of nuclear power is prohibitive. The British government is doing it privately because that is the way the energy market works over here.

The only reason nuclear looked more expensive than fossil fuels was because it has internalised a lot of the costs which are born by the rest of society for coal and gas.

Any sort of emissions tax or carbon tax puts nuclear well ahead, and supply constraints are likely to mean that gas at least will rise a lot in the future.

As against renewables, the only one apart from hydro to give nuclear a run for it's money is wind, which on land in the US with their great wind resource may compete.

In the UK unfortunately most new turbines would have to go off-shore, that is the Goverment's plan, and the costs for that according to Government figures are around twice that from nuclear.

Nuclear plants also have a 60 year life expectancy, so after the first 20-25 years of a nuclear build you start to get power from the old plants at maintenance and fuel costs.

You will probably have to pay more for power than you do at the moment for power from gas and coal plants in the US, but not prohibitively so.

The only thing which looks likely to come in cheaper than nuclear is conservation!

You forgot to mention the VERY long time it takes to get enough nuclear power on-line in Britain to make up the retiring nukes, aand displace natural gas, not to mention coal.

By the time that 7.5 GW of new UK nukes are on-line (a minimal figure BTW, much more are needed even in a Rush to Wind scenario), the UK will be pawning the crown jewels for LNG. Coal appears to becoming scarce on the world markets ATM.

Wind can be built in some quantity quite quickly, more so if built on-shore.

Alan

Perhaps a compromise ? Say a British "Rush to Wind" until 7.5 GW of new UK nukes are on-line and another 6 GW under construction and at least 33% complete ? Then scale back subsidies if the market situation seems to warrant it and cut wind subsidies out all together when the UK has 25 GW of new nukes on-line (and 1 GW of old nuke).

As you know Alan, when I came across the excellent load following characteristics it altered my thoughts on wind power here.

However, if the Government is right on cost it still sounds darn expensive.

My preferred option is expenditure on conservation to reduce the gap, but the government policy has indeed dug a darn big hole and I am not sure if that alone will fill it.

So I would tend to agree that some build on off-shore turbines will be needed, but £40bn is a fair old chunk of change to fund after you have thrown away £100bn on Northern Rock, so perhaps a smaller build would be possible.

Perhaps costs might be held down by building rather more turbines on-shore - the good load following characteristics might make that a more worthwhile sacrifice, as my prime objection to land-based turbines was that if you were just generating a lot of power when it was least needed then it would not be worth it.

The objections of the Scots, Welsh and Irish to building more turbines, as they would see it to benefit the English, though are real and won't go away, and many of the best land sites in England are taken.

Your suggestion on getting the French to build a couple of reactors near the channel and buying all the output might be a good one too.

One way and another it is a real mess in England.

As you know EdF is building one 1.6 GW EPR on the French side of the approaches to the English Channel. A short underseas transmission line to England.

Building two more at the same site (I think that there is room) with the same work crew etc. is the best stop-gap on the supply side. They might be finished 12 to 18 months apart. Get a 35 year contract for all 3.

HV DC to Iceland and Norway also should be looked at.

On conservation, just translating the rules & regs & incentives for new and old buildings from German would be an excellent start. Your climates are not that dissimilar.

As for funds, yes that is a problem !!

Higher rates incentivize conservation at considerable pain. Higher taxes (perhaps on petrol ?) would be a good place to start there.

Best Hopes for the Brits,

Alan

You won't overcome the temptation of the British Government to fiddle with regulations rather than adopt them straight from another country, and in building regs they actually have a point.

The problem is that the British building industry has always been very cyclical, used by successive governments to regulate demand.

In contrast the German industry has been much more stable, and their workforce is very highly skilled.

So for instance British architects have proposed a different way of meeting Passivhaus insulation standards, as they did not think that the very tight standards for air-tightness and the use of mechanical ventilation was possible in Britain.

Instead they have proposed passive ventilation and large porches front and back, which unfortunately would eat into the already limited floor area of British homes.

You might have similar obstacles to just importing standards in America.

In other areas their insistence on British certification is just silly.

The Areva nuclear design has already been passed by the Fins and the French, and other potential designs have been certified in other countries which have very capable regulators.

What do they think they are going to add but more delay?

OTOH they probably feel they have to do this for political reasons.

Actually Alan, thinking about it further a shortfall of 7.5GW should be quite possible to cover with conservation, given the truly awful efficiencies at the moment.

This is about 10% of peak generating capacity. I have no access to information to estimate potential savings in the industrial and commercial sector, but given that they often leave their lights on all night for a start it is presumably of the same order as in the residential sector which comprises 40% of the market.

With 3 million houses out of a total stock of 24million in the lowest insulation band and a further 9 million in the band just above it is clear that massive savings are possible before you even consider other measures like air-heat pumps for the 5 million homes off the natural gas grid or upgrading the power standby specifications of electrical equipment.

Not that I think there is a cat's chance in hell of the Government actually putting a proper co-ordinated program together, but they could surely cover most of the gap if they did.

Jason:

Emotions can run high here. We both know that so much is at stake, we are both taking big personal risks, in different ways, because so much is at stake and we care deeply about the world. Let us honor that in each other. If I have misunderstood your position or ClimateCodeRed's, I apologize. Perhaps you could explain how many cars you do think would be appropriate and why. We have much to learn from one another, let us continue to dialogue and constructively criticize the various options put forward.

An analogy I often think of is that, as a civilization, we are lost in the mountains, and it has started to snow. Visibility is dropping fast. There are cliffs all around, and we are starting to feel a little cold. Things look pretty scary. We are starting to realize that we have made some big mistakes coming up this particular path on this particular day. We were warned, but we ignored the warnings - it looked pretty sunny up here to most of us when we were lower down on the mountain earlier in the day. Now that the blizzard is closing in, some of us are denying that there's any problem, shouting "Follow me, this is easy", and heading straight for one of the cliffs. Others of us are panicking, running about and shouting, "Oh my God, we're all going to die".

In a situation like that, what is needed is to get out the map and compass, huddle round, and with a nice balance of briskness and calm rationality figure out where on the map we are, what the various cliffs around us are, and what way offers the best chance to get the party down off the mountain to somewhere that is tolerably warm and safe. It will be best if we can build a clear enough understanding that the party can agree - it's a bad idea to split up when lost in the mountains.

We know that impulsive decisionmaking can get us in a lot of trouble. Many people thought biofuels a good direction, but instead we find a cliff yawning at our feet as we start to go down that direction. It is important when we look at a particular direction on the map that we ask "how steep is the slope that way?" "If we keep going in that direction, does the terrain get rougher or smoother?"

It is in that spirit that I offer my ideas, and also critique yours. I accept that our society is going to have to make changes, big changes. I accept that we are going to have to make sacrifices. At a minimum, we are going to have to build an awful lot of new infrastructure, which is going to be very expensive. So when you say "instead of telling people the truth and asking for some self sacrifice for long-term survival." I agree with you on the need for that.

But where I have a hard time is that I have found it very difficult to get you to tell me to tell me "the truth" of just how much "self sacrifice" you want us to make along your path. I'm not convinced you know. You won't answer questions about how much of a paycut you want people to take in a relocalized future. You won't present calculations of how many people the world can feed if we stop trading food globally. You want us to take a particular path down off the mountain, but I don't see that you've done the work of figuring out how steep that path is, or whether it comes down to a safe place. I think you need to do that.

It's true of course that climate change is an enormous danger. But it's hardly the only danger here. If we take actions that cause the world to get much less wealthy in a hurry, as I believe the kinds of proposals that you favor are likely to do, then those consequences will not be spread evenly. There will be people who will starve and there will be people who will revolt. Perhaps a lot of people. Social stability is a major concern here. I think you need to think that path through a lot more carefully than you have, and be in a position to convince other people of goodwill that you really have the best path to propose.

And you challenge me in the same way, and rightly so. I presented a scenario for energy use last time that should give you a general idea of the path of future carbon emissions I'm imagining. I believe I've argued pretty defensibly here that the 4 billion cars can be run on less than 10mbd of oil. In general, I propose to move to use renewable energy as the basis of civilization as fast as we can manage without wrecking our society. I will adjust the scenario as I go, and I will continue to try to flesh out more sectors - time limits me - I have a full time job, with mouths to feed and rent to pay. I do my utmost.

In my mind, my scenario is the about the best I can imagine being able to sell the world to do, and probably somewhat better than that really (the world is showing a huge propensity to stay in denial). Obviously, so far, the schemes that environmentalists have been proposing over the last couple of decades have not attracted enough support to have any discernible impact on the growth in global carbon emissions, so I suggest that thinking a lot harder about this question of public acceptability is very important. Splitting off and heading down the mountain alone is unlikely to help either you or the rest of us.