Death Rates and Food Prices

Posted by Stuart Staniford on January 14, 2008 - 11:32am

Ratio of crude food/feed producer price index to all US consumer prices, Jan 1969-Dec 2007. Source: St Louis Fed.

- The total biofuel equivalent of the entire world food supply is a small fraction of the world liquid fuel supply,

- Biofuel production is taking a rapidly expanding share of the (potential) food supply. The share in the US is higher than globally, but in both cases production is growing at around 25%/year.

- In the US, biofuel production has become highly profitable at times in the last few years, and would have been profitable even without subsidies part of the time; the profits are what have fueled the growth.

- If biofuel growth continues at the present rate for even a few more years, it will sharply affect the food supply (it already has had material effects).

- Demand for fuel in developed countries appears to be much less elastic than demand for food in poor counties, raising the specter of a significant fraction of the world's population being unable to afford a minimal diet in the face of competition from the world's drivers.

However, I found my conclusions of last week very depressing and so I have been doing my best to falsify them. I have found at least some good news ("good" by the abysmal standards of last week's post, at any rate). The portion of that post that I was most uncertain of was the connection between food prices and the impact on the global poor. I made a very simple argument based on the global income distribution, and the elasticity of demand for both food (in poor countries) versus fuel (in rich countries).

However, there are several complicating factors here - many people in poor countries are subsistence farmers, and some poor economies are not really connected to the global commodity markets. So this raises the question - how do death rates in poor countries really respond to global commodity markets? One way to explore this is to look at the global food crisis of the early 1970s. This was a major crisis, triggered by high commodity prices, where there were fears of mass starvation. As Time Magazine put it in a 1974 article:

Nearly half a billion people are suffering from some form of hunger; 10,000 of them die of starvation each week in Africa, Asia and Latin America. There are all too familiar severe shortages of food in the sub-Saharan Sahelian countries of Chad, Gambia, Mali, Mauritania, Senegal, Upper Volta and Niger; also in Ethiopia, northeastern Brazil, India and Bangladesh. India alone needs 8 to 10 million tons of food this year from outside sources, or else as many as 30 million people might starve.The causes of the food crisis are discussed in The Word Food Crisis, Periodic or Perpetual, by Dale Hathaway of the International Food Policy Research Institute.Only slightly less serious are the situations in Honduras, Burma, Burundi, Rwanda, the Sudan and Yemen. Additionally, poor harvests threaten food supplies in Nepal, Somalia, Tanzania, Zambia and even the Philippines and Mexico. In Haiti, because of disregard for soil conservation, hundreds of thousands of subsistence farmers face starvation. Whole families are often so hungry that they do not wait for mangoes to ripen; they boil the green fruit and eat it.

Some of the broader dangers were cited recently by Norman Borlaug, winner of the 1970 Nobel Peace Prize for his development of wheat strains essential for the famed Green Revolution. "You cannot have political stability based on empty stomachs and poverty," he warned. "When I see food lines in developing countries, I know that those governments are under pressure and are in danger of falling." Shortages or high prices of food have already contributed to the toppling of governments in Ethiopia, Niger and Thailand.

Food riots have become commonplace in vast sections of Bangladesh and India. "In the worst-affected areas, gruel kitchens have been opened that provide a watery mess of broken wheat, fragments of pumpkin and lentils," reports TIME New Delhi Correspondent James Shepherd. "Queues of several hundred emaciated people at each kitchen get what is often no more than a quarter-pound of the gruel, and sometimes that is shared among six people. In one village, a shame faced elder confessed that Hindus were violating the ban on eating cows and were consuming dead cattle and buffaloes. 'What else can we do?' he implored pathetically."

Even the beggars of Calcutta are better off than the estimated 15 million people now starving in West Bengal. "In the Kutch district of drought-stricken Gujarat," adds Shepherd, "peasants patiently wait for dogs and vultures to finish picking at the carcasses of dead cattle. The hungry gather up the bones and sell them to mills where they are made into bone dust, a kind of fertilizer."

In Bangladesh, there are barely rations to provide even gruel for the starving in Dacca's crowded refugee camps. Children are so emaciated—their flesh clinging to their brittle bones—that they almost look like deformed infants. Shortages of vitamin A, iron and iodine in India and Bangladesh are increasing the incidence—especially among the young—of goiter, blindness and cretinism.

In general, the world did not do badly in keeping up with the increase in demand from 1950 to 1970. World food output increased 0.75 percent per capita per year, and in the developed countries about 1.5 percent. But, this was not enough. The FAO estimated that in 1974 at least 400 million persons were suffering from malnutrition, if not starvation.Ok - enough words. How much did food prices go up, and how many people died as a result?But, though not good enough to prevent widespread malnutrition in some developing countries, world production growth kept pace with world consumption increases until 1970. The first trouble started with the corn blight in the United States in 1970, but the United States had huge stocks of grain to meet the deficit between production and consumption.

In 1972, the weather was adverse simultaneously in the Soviet Union, Asia, and Africa, and world grain production dropped nearly 40 million metric tons, compared to an increase of 85 million tons the previous year and an average increase of 28 million tons per year over the previous decade. As a result of this decline, and the Russian decision to purchase from U.S. markets-a decision abetted by our unsound export subsidies and lack of export monitoring, world stocks, which had largely been held by the United States, plummeted. By the beginning of 1973, grain stocks were down to 10 percent of annual consumption, and prices began to rise, sharply in the United States and wildly in some of the food-deficit developing countries.

In 1973, world production recovered, with over half the increase in the United States and the USSR; but still output did not exceed consumption, and stocks were not rebuilt. Then, in 1974, world output declined again, by over 50 million tons, with the decline largely in the United States and the USSR. By the time of the World Food Conference, grain prices were at record levels. The United States had de facto export controls, and there were no significant reserve stocks in the non-Communist world.

The developing countries, buffeted by high fuel prices, fertilizer shortages, and inadequate grain supplies, were frightened and rightfully so. Some, like India and Bangladesh, faced severe shortages, if not starvation. India and several other countries used precious foreign exchange to buy high-priced food grains, thereby setting back their development plans for years. Concessionary food aid, which had been ample when food was available and low-priced, was sharply reduced, and the largest source of such aid -the United States-refused to commit itself to increasing its food aid in late 1974 when it appeared most needed.

I had some trouble finding long-term price series for agricultural commodities (the USDA numbers online don't seem to go back before 1975). However, I did find at the St Louis Fed, the producer price index for crude food/feed quantities, which ought to give us some kind of reasonable cross section of agricultural commodities. I took the ratio of it to the CPI-U (consumer price index for all items consumed by urban consumers) to look at how food prices were changing relative to just general price inflation. That graph looks like this:

Ratio of crude food/feed producer price index to all US consumer prices, Jan 1969-Dec 2007. Source: St Louis Fed.

As you can see, in 1973 food commodity prices increased by over 60% in a very short time. The initial spike only lasted a month or two, before prices began coming down, remaining at 10-20% above the level of 1972 prices for nine years. (Clearly duration of the spike matters a lot, since the longer someone goes with inadequate food, the more perilous their condition is going to become). Since that time, food commodity prices have been generally getting cheaper, bottoming out in the early 2000s at only 50% of the 1972 levels. This presumably explains much of why the global population has been getting better fed, as well as why farmers have been suffering in recent decades.

In the last few years, this average has started to rise again, but has not risen anywhere near as much as cereal prices (at least, not yet).

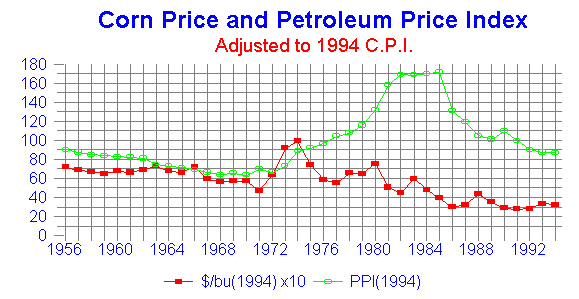

For another viewpoint, I found this graph of long-term corn prices.

Annual price of corn in 1994 dollars, 1956-1994 (red). Source: Ontario Corn Producers Association.

This suggests a somewhat longer shock in corn prices than average food/feed prices - again about a 60% increase, but lasting through 1973 and 1974.

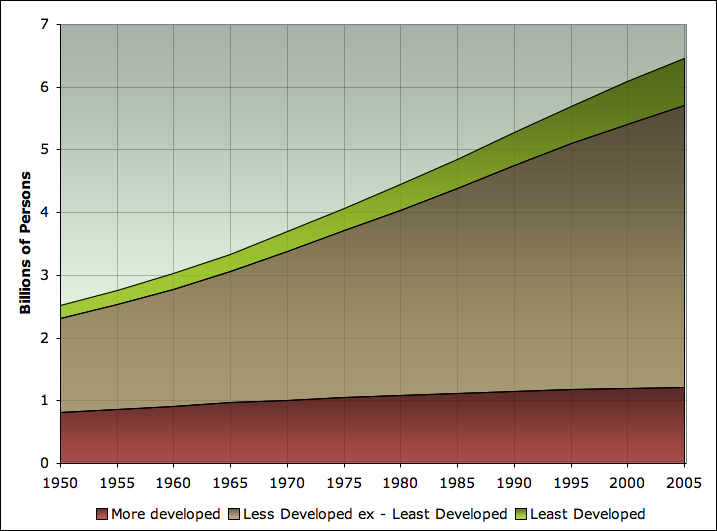

So, now that we understand the order of magnitude of the food price shock, what impact did this have on global death rates? I'm going to use UN population statistics to assess that. The UN divides countries into "More Developed", "Less Developed", and then "Least Developed". The "Least Developed" are a subset of the "Less Developed". This next graph shows the population in each category.

United Nations population split between more developed, less developed, and least developed regions 1950-2005. Source: United Nations: World Population Prospects, the 2004 Revision.

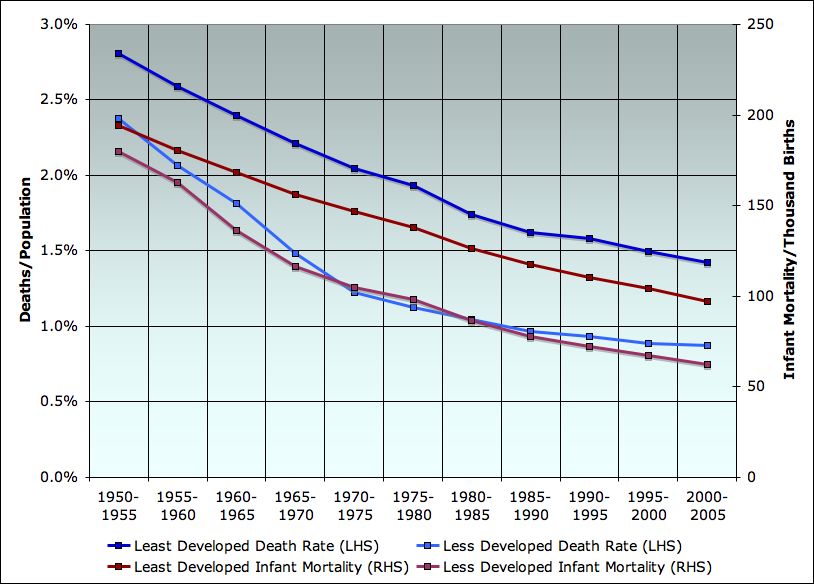

Next, I've plotted the death rates in the least developed countries, and all the less developed countries, as well as the infant mortality rates.

United Nations estimates of death rates per population (left scale), and infant mortality per thousand births (right scale) for less developed, and least developed regions 1950-2005. Less developed includes least developed. Source: United Nations: World Population Prospects, the 2004 Revision.

The big picture is that death rates have been dropping steadily for the last fifty years, and do not correlate closely with commodity food prices. They have dropped by half or more. The main effect is presumably the advent of western medicine gradually reaching the poorest countries (vaccination, antibiotics etc). Clearly, lack of food has not been the main control on the human population over this 55 year period.

However, a more careful inspection reveals a little bump in the seventies when the death rate stops dropping as quickly, as well as another in the 1990s. It's clearer if we look at the change from each five year period to the next in the death rate. Here is is for the least developed countries (it's roughly similar for the less developed, but the graph is too busy with all of them on):

Change in United Nations estimates of death rates and infant mortality rate for least developed regions over prior five year period 1950-2005. Source: United Nations: World Population Prospects, the 2004 Revision.

There are two obvious spikes where the death rate dropped more slowly. My assignments of the likely causes are shown - the one in the 1970s being presumably due to the food crisis, and the one in the 1990s being due to the AIDS crisis (note how the latter affects the infant mortality less than the overall death rate).

This gives us a basis to estimate the order of magnitude of the deaths due to the food crisis and price spikes. If we attribute about 2% of the death rate in forestalled changes, for about five years, and noting that the death rate for less developed is 1 1/4% of around 4 billion people at the time, then the excess deaths are of the order of 5 million people. (Just to stress, I only consider this to be an order of magnitude estimate - it could easily have been 2 million or 10 million, but there was not much chance it was only 500,000 or 50 million).

While I don't wish to trivialize the deaths of 5 million people - it's the same order of magnitude in deaths as the Holocaust - it's a lot less than the elasticity argument from last week suggested. Recall that the USDA estimates the price elasticity of food in poor countries as about -0.7. So a 60% increase in food prices might be expected to result in a 40% reduction in calorie intake, which with much of the developing world either at or under minimal calorific requirements, might have been expected to result in a lot more starvation than it did (hundreds of millions rather than single millions).

I've identified two effects that seem likely to be important. One is the briefness of the worst of the spike (only a few months in the PPI food/feed series). Assuming the series really captures a reasonable cross-section of food prices, this may explain much of the effect, since a few months is not too long to hold on with reduced rations. This is not an encouraging reason, since the causes of the 1970s crises (primarily weather and disease) were inherently transitory, while biofuel induced food price increases might be expected to be long-lasting.

However, the other cause is the fact that a lot of the world's poorest people are (or at least were) relatively divorced from the money economy, being subsistence farmers who grow all or most of their own food on smallholdings, and thus are relatively insulated from commodity price shocks in global markets. Let's explore the trends in that.

Subsistence farmed landscape in Kenya. Source: Michican State University.

We might expect that the urban poor, who must buy food somehow, are more likely affected. Folks living in houses like these, which surround and invade most third world cities, are not in a position to grow much food:

Shantytown in Capetown, South Africa. Source: Capetown.dj.

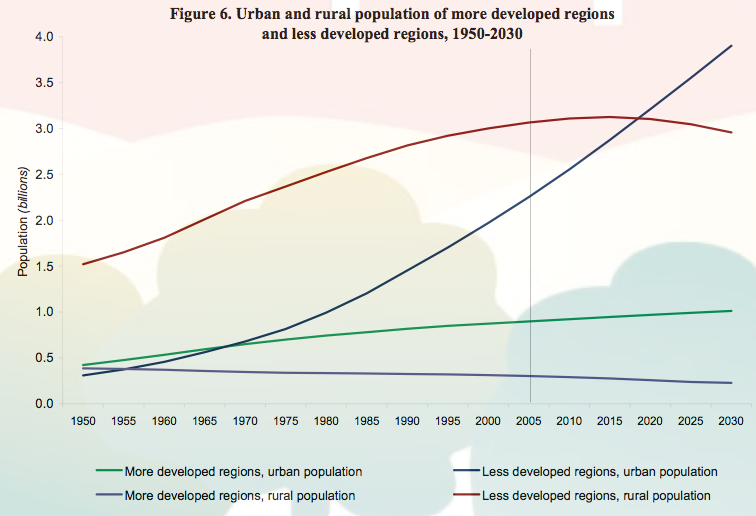

So, what fraction of the developing world is urban versus rural? Another UN population report has this data:

United Nations estimates of urban and rural populations for more and less developed regions 1950-2030. Source: United Nations: World Urbanization Prospects, the 2005 Revision.

The urban population of less developed countries has roughly tripled since 1970, while the population of rural regions in those countries has increased about 50%. In 1970, it used to be that the developing countries were about 75% rural, but now they are on average a little under 60% rural. Clearly the vulnerable urban population is much larger than it was. However, it's still the case that more than half the population of developing countries is rural. Are they mostly net food producers who are insulated from global commodity price increases?

This question, as well as a number of other relevant ones, is addressed in a very useful World Bank report, World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development. In chapter 1, we find:

An estimated 2.5 billion of the 3 billion rural inhabitants are involved in agriculture: 1.5 billion of them living in smallholder households and 800 million of them working in smallholder households.So the vast majority of the developing rural population is living or working on small farms, and thus is somewhat insulated from global commodity prices:

Even with globalization, the staple crop sector remains largely nontradable in substantial parts of the agriculture-based countries for two reasons. First, locally grown staples such as cassava, yams, sorghum, millet, and teff, which are not internationally traded (although sometimes regionally traded), often predominate in the local diets. Second, the domestic food economy remains insulated from global markets by high transport and marketing costs, especially in the rural hinterlands and in land-locked countries. In Ethiopia the price of maize can fluctuate from around $75 per ton (the export parity price) to $225 per ton (the import parity price) without triggering international trade. This nontradable staple crop sector represents 60 percent of agricultural production in Malawi and 70 percent in Zambia and Kenya.In many developing countries, most of the poor are in the rural areas:

More than 2 billion people, about three- quarters of the rural population in developing countries, reside in the rural areas of transforming economies, encompassing most of South and East Asia, North Africa and the Middle East, and some of Europe and Central Asia. Although agriculture contributed only 7 percent to growth during 1993–2005, it still makes up about 13 percent of the economy and employs 57 percent of the labor force. Despite rapid growth and declining poverty rates in many of these countries, poverty remains widespread and largely rural—more than 80 percent of the poor live in rural areas.In rural sections, food price increases may help some households, by improving their incomes, even while other households suffer because they still have to buy a fraction of their food:

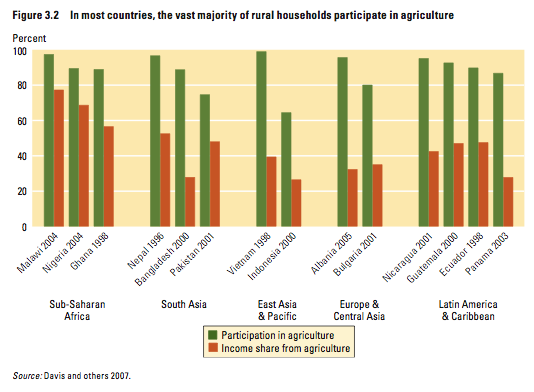

From 1981–2003, 1 percent GDP growth originating in agriculture increased the expenditures of the three poorest deciles at least 2.5 times as much as growth originating in the rest of the economy.Unfortunately, although most rural households participate in agriculture to some degree, over half are net food buyers, since only a portion of their income comes from agriculture:Similarly, Bravo-Ortega and Lederman (2005) find that an increase in overall GDP coming from agricultural labor productivity is on average 2.9 times more effective in raising the incomes of the poorest quintile in developing countries and 2.5 times more effective for countries in Latin America than an equivalent increase in GDP coming from nonagricultural labor productivity. Focusing on absolute poverty instead, and based on observations from 80 countries during 1980–2001, Christiaensen and Demery (2007) report that the comparative advantage of agriculture declined from being 2.7 times more effective in reducing $1-a-day poverty incidence in the poorest quarter of countries in their sample to 2 times more effective in the richest quarter of countries.

World Bank estimates of participation and income shares for rural households in various developing countries. Source: World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development.

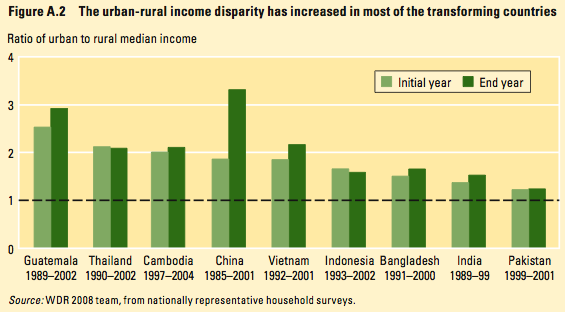

Moreover, it's not the case that urban incomes are in general massively larger than rural incomes - in most cases, the median urban income is less than twice as much as the median rural income:

World Bank estimates of urban and rural income ratios for various developing countries. Source: World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development.

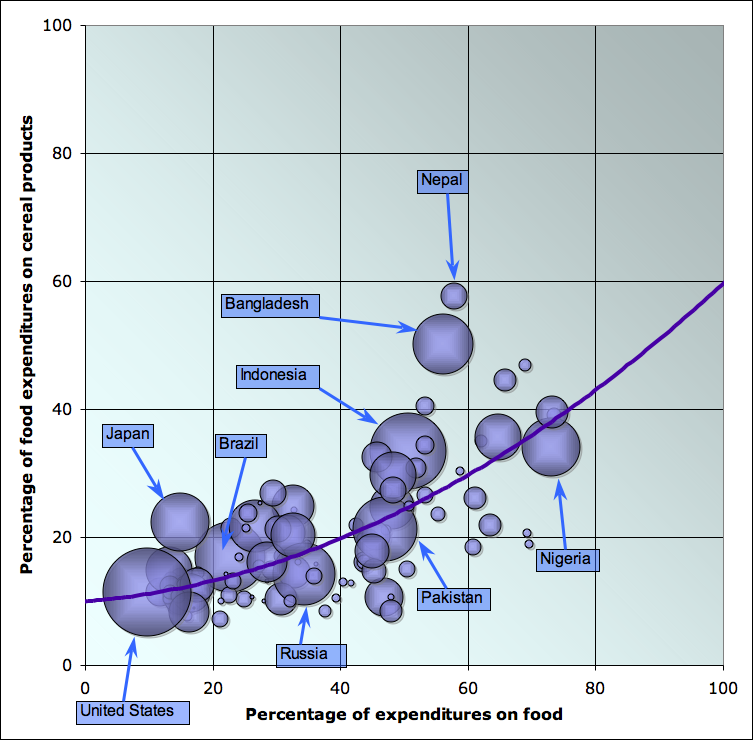

And if we look at the share of income going on food in poor countries, that too suggests vulnerability. This next graph shows the share of food expenditures going on grain products, versus the share of all expenditures going on food for a sample of countries. Bubble area is population. Note that some important countries are missing, including India and China.

Share of food expenditures going on bread/cereal products, versus share of all expenditures going on food for a sample of 114 countries. Bubble area is proportional to country population. Trendline is a quadratic fit. Source: USDA Economic Research Service: International Food Consumption Patterns.

It's worth noting that much of the developing world spends half or more of its income on food. Also, given that cereal products are generally the cheapest food, and this graph shows expenditure fractions, the dependency on cereal products for calories is very high at the poorer end of the scale.

In summary, it still seems to me that a sustained increase in food prices by factors of several fold, and that lasts for years, has the potential to deprive a material fraction of the global poor of enough food to live. This would be a much worse food crisis than the 1970s food crisis. Whether biofuels have the potential to bring that on depends on the future trajectory of oil prices, a subject that will have to await a future post. I'm keen to understand this issue as quickly as possible, as we do seem to be entering another food crisis of some scale. Here's an excerpt from a recent warning by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

17 December 2007, Rome – FAO is urging governments and the international community to implement immediate measures in support of poor countries hit hard by dramatic food price increases.If we weren't converting over 5% of the global food supply to biofuels already, would this be happening?Currently 37 countries worldwide are facing food crises due to conflict and disasters. In addition, food security is being adversely affected by unprecedented price hikes for basic food, driven by historically low food stocks, droughts and floods linked to climate change, high oil prices and growing demand for bio-fuels. High international cereal prices have already sparked food riots in several countries.

In its November issue of Food Outlook, FAO estimated that the total cost of imported foodstuffs for Low Income Food Deficit Countries (LIFDCs) in 2007 would be some 25 percent higher than the previous year, surpassing US$ 107 billion.

SS - you are a machine

I haven't read this yet, but wanted to reiterate that since your Fermenting the Food Supply piece last week, which pointed out the disparity on the elasticities of driving/eating, grain prices are up OVER 10%. Today at noon EST , and the same on Friday, all 3 grains are limit up, ( beans 50c a bushel, corn 20c and wheat 30 c). Irrespective of whether this is due to commodity hedge funds piling on board, we may see your food/fuel hypotheses unfold in real time, and quickly.

The sliced lite wheat bread I love to get at Krogers, has been $1.00 per 16oz loaves for years; however, this week it shifted to 4 for $5.00.

A 25% hike in price that actually hits home.

I suspect I have purchased my last dollar loaf of bread...

If you keep track of the retail price of wheat flour, you'll see that you've had a delay in the increase in price. I make my own bread and flour has been around $0.50/lb since Thanksgiving. You could usually find it on sale for $0.20/lb before that. Ho hum.... At least I don't feel so bad about stretching it with organic rye flour....

I notice that Europe is moving quickly to ban imports of some biofuels. I mentioned this on the prior article but it looks as though they have worked out their draft. The main concern is with preserving forests and grasslands but I expect that they'll move against displacing food soon, probably by going after nitrogen inputs. It is amazing what contortions the WTO puts us through.

Chris

http://science.reddit.com/info/65g32/comments/

http://politics.reddit.com/info/65g39/comments/

http://www.digg.com/world_news/Death_Rates_and_Food_Prices

We thank you for helping us spread the work of The Oil Drum around to interested parties.

One other item to factor into the food supply equation is the new strain of wheat stem rust that is hurting crops in parts of Africa and the middle east. No resistant strain has yet been developed, therefore, it is likely there will be greater demand for imported grains in these countries.

With little grain stock carry-over, it appears we are approaching JIT food production.

Todd

Stuart,

great two pieces

I think the factor which will sway US government is the food prices in the US, and the increasing percentage that this takes out of the average budget

I was looking for numbers on this. I belive the percentage was 16% of average income spent on food (and they say 4% spent on fuel today)

If this 16 goes to 20 or 25%, there will be howls - in an election year.

This may make the govt change course

Here's a perverse idea:

As we know, there is good evidence that the energetic gain on biofuels from food crops is rather crappy. And they affect world food supply.

But maybe there is a silver lining. i.e. The biofuels effort is bringing closer to the present the day of reckoning, but at the same time supplying a cushion. The high prices send a signal around the world and presumably ring everybody's bell. Obviously, the 'cushion' is logistically not nearly as good as grain supplies for a number of reasons. But it would seem not completely crazy to think that biofuel production could fairly rapidly cease without massive economic damage because it doesn't contribute that much anyway.

These price signals are very important. If the world is near the brink, it's better it knows before the real brink appears.

It's not something the Oil Drum would necessarily like to crow to the media about, but I think it likely that the site did the world a huge favour in contributing to the rise in distant future oil contracts. If hedge funds made money on Stuart's

adviceresearch then there's a good chance the price was affected.Greenspan who has always watched distant future oil very closely recently said in the WSJ that "oil is going to peak earlier and lower than previously expected".

Shows how uncovering the facts can give you an audience with the powerful (indirectly). Perhaps Stuart rang Greenspan's bell.

I guess another way to present this admittedly bizarre idea is say maybe it would be good if the world had a large food cushion but that it was hard to access. Sorry for the flippant analogy but it could be sort of like knowing you can always get money from Dad but at the cost of a 3 hour lecture and being reminded about it for the rest of your life.

Speaking of bio-fuels and peak oil... If one believes in man-made global warming then bio-fuels (CO2 Absorbing) are a really good idea and CTL and GTL (Lots of CO2) are really awful ideas. If one believes in peak oil and not man-made global warming then bio-fuels are a bad idea (Bad EROEI, Misuse of arable land and limited fertilizer) and CTL and GTL are good ideas (Scalable, Good EROEI, Produces Fertilizer). If one believes in both then negative EROEI bio-fuels are a bad idea and one's opinion of CTL/GTL really depends on whether your more afraid of peak oil or global warming.

Thank you again for the research, Stuart. I think your analysis is excellent.

It is worth noting that "urban" does not inevitably mean "without the capacity to raise food" either. The substantial percentages of urban agriculture in poor world nations (the last figures I saw for Lagos, for example, suggest that 1/3 of all meat and egg products, and 1/4 of all vegetables - including staple vegetables - are grown within the city limits.) In Lusaka in Zambia (which has the highest rates of malnutrition in Africa, unless Zimbabwe has recently beaten it out), more than half the population gardens, either in the rainy season or year 'round, and those who garden have rates of malnutrition 64% lower than those who do not, even adjusted for the differences in wealth created by property ownership. Dmitry Orlov notes that "survival" gardens in the former Soviet Union after the collapse were typically 100 square feet (in Moscow, by the height of the collapse 65% of the population was involved in agriculture and this is widely considered to be the reason that virtually no one starved), Roberta Baer notes that in small cities in the Mexican Sonora, the agricultural difference between life and death for most urbanites is about 150 square feet, and there are plenty of other examples. One comes here - this took place in the US and not in a city, but is fairly easily duplicable in many places with a comparatively small economic investment - you don't even actually have to have soil:

http://casaubonsbook.blogspot.com/2007/11/my-friend-pat-can-feed-world.html. I personally have seen similar "pot in a pot" container gardens in poor world nations, made out of old food pots.

I don't have your gift for numbers, but it seems as though the intersection of higher urban salaries *COMBINED WITH* gardening may be the potential salvation of poor urban dwellers. That is, relying entirely on purchased food is probably inadequate - but purchased food plus wild gathered foods plus gardening/microfarming offers some measure of insulation. You might consider taking up the merits of the gardens you are softening on among your next analyses ;-).

I say none of this to minimize your concern about the apocalyptic potential of biofuel production, which I share, but to observe that the potential for mitigation may be greater than expected, but that the *kind* of mitigation we advocate (although with an attempt to stop the rush to biofuels) matters as much as the fact that it is possible - that is, it may never be possible to raise prices and provide adequate food aid - the UN for example is already widly overstretched. But it may be possible to facilitate and enable urban gardens. This is not as useful as not starving people in the first place, but it is always wise to have a backup plan.

Note, btw, a UN agency recently made the argument that cities must do more urban gardening for other reasons - in response to climate change and rising population: http://www.reuters.com/article/environmentNews/idUSL1951495520071219.

Cheers,

Sharon

Yes, and it's important to remember that swelling urban populations in much of the developing world consist of recently arrived, if not first generation peasants streaming in from the countryside. Not only are cultivation practices remembered and even sustained (home gardens are big in Peru and much of Latin America, for example), but people go to great lengths to maintain ties to their home communities, such as fulfilling cargo duties to local community feast day celebrations. Remittances from the city (or even from the US back to Mexico, for example) are as much about validating one's membership in the rural community - "just in case", as supporting family there. Investing in social capital as insurance.

I don't even think you have to go that far. Most of the recent rural to urban migration in poor countries is really family members, that will, without a doubt, move back home to the family farm in the event of a crisis. It's not really that they are investing in social capital. They have transiently moved to where they can make better money. In the event of a famine, this tide will reverse, and the urban poor will quickly migrate back to the countryside.

Once back on the farm, they will quickly reintegrate with the village because they never really left in the first place.

Also, in the real event of a famine, the idea of mono cropping cereals for cash will be ditched quickly. These people may be poor, but they aren't so stupid they will accept death. The cereal crops they raise will be abandoned for integrated gardening just as quick as they can manage it. This will put further pressure on grain prices, but will allow much of the poor to live out a crisis. Most rural families who import food do so because it is relatively easier to grow a single crop, sell it and buy what you need than managing a complete garden, especially when several family members are earning money in the city and sending it home.

No, the 3rd world poor will quickly adapt during food scarcity. They are only a decade or two removed from it, and the knowledge hasn't been lost.

It's the first world non immigrant poor who will starve. That's where the crisis will be.

How many people in the first world died of hunger in the seventies food crisis?

Hi Sharon,

I am in full support of urban gardening and do believe that it can prevent malnutrition and perhaps keep starvation at bay in crises. I do wonder how significant small-scale gardening is calorie-wise, however.

For example, potatoes or sweet potatoes are foods that yield a lot of calories per unit area cultivated. A decent yield would be 1 lb of potatoes per square foot. Since potatoes are 350 calories per pound, this is 350 calories per square foot. A 100 sq ft garden might then yield 35000 calories. Most people would want to eat about 2500 calories per day, but can get by with less in emergencies, so let's say 1900 calories per day. That potato patch would supply the calorie needs of 1 person for 18 days under rationing conditions.

That's why I don't see urban gardens as significant for calories, but I do see them as significant for vitamins, minerals, food diversity and saving the poor $ that could be spent on staple foods and health care.

A diversity of vegetables might only have ca. 200 calories per pound, but it is rich in other ways. Vegetables are also best eaten fresh, so best to be eaten soon after harvest, which is difficult to accomplish in cities. A person may want to consume 500 lbs of fruits and veggies per year, which in a garden setting may require only 500 square feet. This would be about 100,000 calories from fruits and veggies for a year.

So yes, urban gardening is doable, valuable, and should be encouraged. But fields of grain are needed to supply enough calories to support the energy needs of a person, which is about 850,000 calories per year. And the grains need to be grown in areas that are beyond the scope of urban gardens. For example, in an intensively managed garden setting one might yield 10 lbs of grain per 100 sq ft. A person might need 300 lbs of grains per year at 1600 calories per pound to yield nearly 500,000 calories, but this would require 30 x 100 sq ft = 3000 sq ft per person, or six times the veggie area.

With heroic assumptions, including great soil, plenty of water, inputs of fertilizer, and highly skilled labor, it might be reasonable to grow enough food for a person in ca. 6000 sq ft, when paths between beds are included. That's about 1/7 th of an acre. A household would need 1/2 an acre.

I just try to keep these figures in mind because I don't want people to get the idea that they can feed themselves, and the poor can feed themselves, without access to good land, in adequate amounts, and fresh water. At the same time, I don't want to throw cold water on the necessary enthusiasm behind urban gardening/farming.

In the U.S. of course there's something like 1 acre of paving dedicated to each automobile, and there are nearly as many cars and light trucks as there are people. Room for improvement.

Apologies if I wasn't being clear - I am not claiming that urban areas can be self-sufficient in food, or that calorie crops produced on a larger scale are not essential - merely that, for example, those 18 days worth of calories can make the difference between starving to death and mere malnutrition - or between malnutrition and a barely adequate diet. My mention of staple vegetables was simply to observe that the idea that vegetables provide minimal calories is not always correct. Let's imagine a 200 square foot plot for a family of four, for example. Such a plot, intensively managed, could produce enough dense calories for, say four or five full days of additional survival, or more likely, 10 or 12 days of marginal survival. That's a big contribution to the yearly diet for a person suffering from malnutrition. Then add flavorings, nutritious greens, some leguminous protein crops a couple of chickens running around for eggs, fat and proteins, fed mostly on weeds, scraps and garden wastes. There are probably two full weeks of survival no one has to pay for (amortized over the course of the year) plus supplemental nutrition. Given that the majority of the world's poor spend 70% or more of their income on food, 2 weeks of not buying food is an enormous difference in their lives - think about how large a percentage of your income 2 weeks salary that can now be applied directly to future food purchases would (not a perfect analogy, I know).

Again, it isn't my claim that people can live on 100 or 150 square feet - far from it. But gardens in fairly small spaces can make a critical difference in diets, providing a margin for survival. Nor am I claiming that this will keep billions people who are being systematically starved alive - far from it. Merely that any analysis of the mitigating factors might wish to include the nutritional and caloric content of garden production.

It is also useful to think about the aggregate effects of such gardens - for example, Michael Hamm and Monique Baron have calculated that 3 million 200 square foot gardens in the state of New Jersey, *plus* existing farmland* would be sufficient to feed the state - if the gardens were planted into appropriately nutritious crops. That is, such a 200 square foot garden won't feed a person for a year, but the supplemental value does dramatically reduce the total amount of arable land required to feed a given region. Does this make sense? That is, gardens do not function as simply "supplemental, uncounted" calories - they produce some tiny percentage of needed calories, which added up on large enough scale, makes a huge dent in the practicalities of needed farmland.

There are number of fascinating analyses of this data in Koc, McRae et als _For Hunger Proof Cities_. But your larger point stands - no one is going to be producing all their food on a rooftop, and we will all need calorie crop production. Cuba kept importing rice, and Russia kept growing and importing wheat during the worst of their crises. But I think there's at least as great a tendency to underestimate the potential of small scale food production as there is to overestimate it.

Sharon

I am in agreement with you. Thanks for the leads on other studies. Much appreciated.

Ironically, that same analysis would indicate that a lot of the residents in U.S. cities are screwed. Most residents do not have access to a 10x10 plot much less the wherewithall to garden it.

In a pinch people will be quick studies. I know crap about gardening but I know people who do and in a pinch I can count of them.

we could have community gardens on roofs, gardens on porches and in abandoned lots. parks could be converted.

John15 - Nice thoughts but totally unrealistic. Both gardening and farming are learned skills. Plus...you need appropriate species and cultivars, a good growing medium, water and fertilizer. I grow a lot of stuff but I don't have enough seed for the other people in my immediate rural area (about 8 of them) much less enough seed for a community garden.

And, as Bob Shaw has so often posted, there isn't going to be enough fertilizer. Heck, I stock about 300# of 20-20-20 soluble for fertigation plus, maybe, 500# of 15-15-15 prilled fertilizer plus some rock phosphate and I can tell you these won't go far.

Anyone who thinks they're going to grow any significant quantity of food sort of on the spur of the moment is going to starve.

Todd

Well, historically, in the West, we used to provide allotments for new developments, particularly government housing for low socio-groups. I visited a back-to-back scheme (mid-industrial revolution) in north England, where each house got a place to have a pig!.

Maybe we should have new planning standards that require a given allotment area per population. (well its much better than all that stupid space put to road verges! I know they are popular (in walkable neighbourhoods) here in the UK, because most of the good ones have waiting lists and are visibly well used. Even wealthy westerners could save a good lot of money growing their own food given today's stupid prices.

The area your talking about was called a "sowcka"{sp?}and is 100 sq meters not ft

There are 3 elephants in the room:

1)population

2)perpetual economic growth

3)equality

To delve too far into these 3 subjects has become almost politically unacceptable compared to just a generation ago, when it was just uncomfortable.

So here we are, discussing that allowing people to starve at the expense of allowing others to drive is the moral hazard. To follow this path of reasoning is to suggest greater global equity is needed.

But would that solve anything? I believe the IPAT equation (Impact = Population X Affluence X Technology) is flawed, because it doesnt take into account WHY we consume and WHAT energy and resources culture makes available. I would change the "A" to 'Aspiration' and the 'T' to 'Trinkets'. This would be more fundamentally consistent with a)our evolved penchant to compete and acquire status in whatever currencies culture signals us to and b)our neural reward pathways that are hijacked and quickly habituate to novelty items that use more and more energy in a culture of energy abundance (at least at the top).

So if somehow we do keep all these less and least developed nation people supplied with food, at some cost to our cheap liquid fuels, then there will be even more people around that 'aspire' to the goals of economic growth, and living a high energy lifestyle. e.g. we are distributing wheat in a truck with a big Green Carrot advertisement.

Thanks Stuart for delving deeper into these issues. They are uncomfortable but need to be addressed. The problems of resource depletion cannot ultimately be solved unless we address a)population, b)infinite economic growth simultaneously with c)equity. Perhaps instead of Al Gore winning the Nobel Peace Prize it should have gone to the guy in China who instituted the one-child per family policy...

I agree with the three elephants, although I would label the last as INequality. Population has to go down (either under our -- human -- control, or nature will take care of it). Economic growth has to reverse, will reverse -- again -- one way or another.

Which brings me to the last point: a new kind of efficiency is going to be required of mankind: we are going to return to the soil. But the soil (and much else) is not what it was prior to agriculture, it's not what it was after the fall of the Roman Empire where small holders could eke out a living where slave-based latifundia could no longer work. It is going to require a re-direction of human intelligence and human creativity to rebuild our relationship with the natural world and reintegrate ourselves into it. This work (centering on the soil) cannot be done by slaves, by serfs, nor wage (or salary) slaves.

Great as our science has been, there's crudeness to it, based on digging and sucking resources out of the ground, tearing things into pieces and wondering why they don't work anymore, and slapping things together that, when you really look at them, are absolutely nothing compared to even a bacterium. Our greatest resource (ultimately, our ONLY resource) is the pulsating web of life that is the surface of the planet, the web that we have been tearing up as we might that of a spider, of this we are barely at the earliest stages of knowledge.

Marx envisaged exploitation ending by the people taking over, expropriating the machinery and technology of advanced capitalism. Wrong about that. The issue now is not shared abundance, but survival. The struggle for human survival, might, I think, require the abolition of (or better, have no room for) vast disparities in wealth , and that everyone get his hands dirty (although I hope we are not forced to work as hard as Stuart :) ).

Since I expect I'm not the only one who had to look up latifundia

I suspect that economic inequality is a bigger issue than most people think. One doesn't have women's rights, gay rights, civil rights, human rights, reproductive rights or rights of any kind unless one has economic rights and economic power. Because vast chunks of the global population have been so disempowered, they will continue to suffer. The easy solution for the powerful will be to maintain the lifestyle of the rich and powerful at the expense of the increasingly poor and powerless and to make a larger and larger share of the overall population poor and powerless. The nation states will lose all legitimacy when they can no longer supply enough bread and circus and general well-being. It can fall apart for any number of reasons.

China was able to implement one-child policy. I wonder if that could have been done by a government widely perceived as totally illegitimate. That would be only one example of how a perception of sharing the burden is going to be necessary to addressing any of the other Big Issues: toxic planet, climate change, unbounded growth and resource depletion. That's why I talk about economic inequality along with those; it's a necessary part of the fix - at least as far as we humans are concerned.

cfm in Gray, ME

Thanks again Stuart. I think you are correct in emphasizing that a short-term food crisis is different than the likely long-term rise in prices we now face.

I had a question about this:

"Unfortunately, although most rural households participate in agriculture to some degree, over half are net food buyers, since only a portion of their income comes from agriculture"

I have heard this before, i.e., that even subsistence farmers often don't grow enough food for themselves in some places, but I don't understand this sentence or the importance of the associated graphic. First it is pointed out that much of what is grown by subsistence farmers is outside of the commodities market (that's why they are subsistence!) and so wouldn't it never show up on their "income" estimates? Or, do I not understand how the statistics are put together. Do the economists take the food grown by subsistence farmers for themselves and estimate the monetary value of it, thereby giving them a pseudo-income? Then do they estimate how much food this represents, see that it falls short of what they need, and then estimate how much they need to buy?

I mean, so what if only a portion of their income comes from agriculture. None of it could come from agriculture and they could theoretically be feeding themselves plus surplus. I summary, I need some better understanding of how the "half are net food buyers" is figured out and why this has anything to do with their income from agriculture.

My point in including it was to note that, just because a household has some involvement in agriculture, does not mean food price rises benefit it - most households in rural areas grow some food, but nonetheless most are net food importers.Thank you, that answers my question perfectly, confirms that even many subsistence farmers are not growing enough for themselves, and that indeed monetary valuation was used to quantify this for comparison purposes. Your point is valid and well taken.

"even many subsistence farmers are not growing enough for themselves" I wonder how much rural population growth is the cause of this, and whether it was true in 1970?

It occurs to me that what we might expect under these circumstances is for land to concentrate, at least wherever there is enough infrastructure to provide access to markets. Households with larger and/or better-managed landholdings will benefit from price rises, since they can sell their surplus in the market. Households with smaller and/or poorly managed landholdings will suffer as they have to buy food at rising costs. A short-term solution (actually strategy of desperation) for the poor households is to sell their land to the wealthier households.

I wonder how much globalization is the cause of it.

I think this is probably exactly right. For example, in Bangladesh, where a typical extended family of 7 might have two plots of land, both well under an acre, and considerable crop loss to intermittent difficulties - as well as calorie consumption too low to support intensive farm labor, this is a deeply losing prospect. On the other hand, urban dwellers who might have access to rural land or urban gardening might find that they are able to partially mitigate some of the harm by supplementing a primary monetary income with food they don't have to buy - that's not to say that their prospects are good, just that historically speaking, the very worst poverty is often in rural areas, followed then by the urban poor, and then everyone else.

I'll be interested to see how this plays out in the US as well - US consumers have few rural ties, and little experience growing food. In the very near term, gardening is unlikely to be rapidly profitable for them. As food *and* gas prices rise, the number of people unable to buy adequate food will also likely rise, along with the cost of nearly everything else. In the US, many people are now or soon will be spending approximately the same percentage of their income on housing as they are on food - and if the market remains very soft, are unlikely to be able to unload that debt. Nor are the working poor likely to be able to dramatically reduce the gas they use to get to work, to get the kids to daycare, etc.... They could turn off the power, but many suffer intermittent utility failures anyway, and since no electricity or running water is often grounds for CPS to come and tak your kids away, most of them won't dare. So while the current percentage of American income spent on food is quite small, it isn't clear to me how practically flexible (as opposed to technical flexibility) the budgets of the American poor. Right now only about 3% of all children who experience food insecurity and 6% of all adults who fall into that category actually regularly go hungry. That is, while there is a fair bit of intermittent hunger in the US, we don't see pictures of large numbers of children suffering from acute malnutrition and hunger - but we might yet. This year the Boston Globe reported rising numbers of children who experience heating season malnutrition - their parents have to spend money they would normally spend on food on heat, and the children go hungry, which leaves the children unable to keep their bodies warm enough, which creates a viscious cycle of hunger and cold-related illness and other consequences - including death, periodically. The results you anticipate may not be so very distant in all cases.

Sharon

I feel that most of those that we consider to be poor in the USA do not understand that they can substitute rice and beans for instant macaroni and cheese. The foodstamp system in place can provide the necessary calories, even if the appeal of those calories is much lower.

This conversation has some biases, but having lived on foodstamps once, I feel that there is no reason for us to see hunger IF those people can retain housing. The bigger problem then becomes affordable housing for the population that will become unemployed as the workforce contracts due to much higher energy prices. Displaced people will be a much bigger issue in the USA as we move past peak.

You are very right to note IF they can retain housing. Rice and beans is not a real option unless you have a good kitchen. When I was a college student in the late 70s, many of us had food stamps and we cooked massive dinners in a large communal kitchen with multiple stoves and refrigerators. [12 of us hippy types in that one house.] We spent those food stamps at the Cambridge Food Coop on bulk grains and produce. We ate far better than the students in the dorms with cafeteria meals.

If one is homeless, that extra work preparing inexpensive but good food is not an option. One can't exactly carry around 50# bags of rice.

cfm in Gray, ME

That is indeed a short-term solution often chosen. Unfortunately it leads to famine and conflict.

In the densely-populated valleys of Rwanda in the 1980s onwards, the average farmland per person became 0.2 hectares, the average farm size less than a hectare. A study after the conflict noted that even in almost entirely Hutu or entirely Tutsi areas, about 10% of the population was still killed by their neighbours. The people killed were commonly those with a couple of hectares to their name. If your 0.2ha is providing you with almost enough to get by, the guy with 0.3ha all to himself looks obscenely rich.

Now, whether the genocide was fundamentally an ethnic-motivated one and some hungry and envious people just took the opportunity to wipe out annoyingly rich neighbours in the general chaos, or whether it was fundamentally economic and the ethnic stuff was just cosmetic, doesn't matter here. What's important is that when people were so close to the starvation line, a few hundred square metres here or there meant a lot, and as well as the food problems, created or exarcerbated social problems.

My sense is that as long as small-scale farmers have access to decent tools and sufficient land area to provide for their own needs, they are often the most efficient managers. However, when short-term profit motives are combined with access to high energy capital, that's when to watch out! And of course there are a lot of people with inadequate land holdings and inadequate capital who damage their lands, enter a vicious downward spiral and end up squatting in urban slums.

That's iffy because it presupposes a continued well-organized and socially supported market. The concentration of resources in the FSU was not due to what one normally considers a well-organized market. Yeltsin decided to privatize (loot) and - much to the chagrin of the WTO clique - he decided to keep ownership largely national. Hence the russian oligarchs and the capture of the Russian parliament. In Iraq, the Bremer rules made sure that mistake (letting the Iraqis plunder themselves) would not happen. In neither case does the transfer of ownership have anything to do with "better management" in any "usual" sense.

cfm in Gray, ME

I wonder why our legislators can't make the connection between the farm bill, corn ethanol subsidies and illegal immigration. Where do they think a Mexican corn farmer will go once he is forced off his land by the "solution" stated above?

Which brings up the topic of migration as it relates to all of this. I suspect unregulated consolidation of land could force even more people into cities at a time when what we need, to a certain extent, is a bit of reruralization.

Another question Stuart. I am wondering if you had looked into changes in how the CPI is calculated.

See: http://globalpublicmedia.com/ron_cooke_cpi_sophisticated_economic_theory...

Some are arguing that without the politically motivated methodological changes to the CPI made in the past 10 years or so that the official inflation numbers for food would be much higher. I don't know how difficult this would be, but I would like to see your food inflation graph using the previous methods.

Not that I am asking you to do more work. This is what Nate should spend his time on. ;)

very funny. ha. ha....:)

Nate,

Here's something to file in your neural-pleasure notebook. It seems that the same wine excites the brain more when the consumer is told it costs more...

http://www.news.com/8301-13580_3-9849949-39.html?tag=newsmap

Thanks. Though I doubt the same mechanism applies to ethanol...;) (a post for this type of discussion coming later this week)

That work has already been done, multiple times, by other people. Some of them go so far as to make their living selling corrected CPI data to Fortune 500 companies. I won't bother to list them all because after having done so in the past, those posts are attacked here by those whose heads are buried deeply in the sand.

Oh, man, I haven't seen your previous posts on this topic. Care to indulge me? I already don't trust the numbers and won't attack.

John Williams is the most famous practitioner of reality-based CPI adjustments . . .

http://www.shadowstats.com/

p://www.thestreet.com/video/index.html?clipId=10398519&channel=Cramer+On+Demand&cm_ven=YAHOO&cm_cat=&cm_ite=#10398519

ag prices soaring on scarcity - Cramer

getting very mainstream.as nate said 2 days

10% limit up. he connects price increase to oil too.

thanks for continued focus stuart.

The subject is complicated even more by the demographic transition(s). The 'wealth effect' can, in some ways, be graphed by the amount of food/capita available. This has been going up fairly steadily since ~1950 (green revolution) and world-wide birth rates and fertility rates have been trending downward in the same time frame. As we well know, trends aren't forever and it looks like we are going to have a crunch between about now, when food production appears to be peaking, and about 2050 when the population trend supposedly will level off actual population growth. Add to that a net downward pressure on food supplies because of conversion to biofuels as well as waning fossil fuel supplies and we end up with a volatile mix. It doesn't look good to me and I can understand why Norman Borlaug is speaking up now about the issue. It looks to be getting worse even ignoring the biofuel issue.

Norman Borlaug was speaking up in 1974 :-)

Another issue here with the whole food and fuel thing is that the US is a massive net exporter of food calories.

With the biofuels push, those net exports are falling. More of them are being consumed at home partly analogous to the situation in many oil producing nations.

Yet, the world is a little hungrier, as grains stocks erode. The bargaining position of US in an oil-scarce world may not be as bad as one might think. (as long as they are willing to screw the ethanol producers)

Food production is a function of land, water, fertilizer/pesticides, sunlight, technology, and labor. The US has a (relative) abundance of most of those inputs. But the technology of our food production is heavily dependent on liquid fuels (and natural gas). So in the fuel/food equation, once accelerated decline rates and increased imports of liquid fuels are considered, we may not be as big of 'net food exporter' as we think.

But, I thought we wuz in the outs. :)

I agree, a detailed look at the whole equation is needed.

However, you can't eat oil. And the food weapon can be quite powerful. I believe the US used it to help Egypt come to terms with Israel's existence.

It certainly provides additional incentive for the US to take a close look at farming practices. i.e. it's long-term status in the world.

yes. you can - in extreme case. synthetic food can be made from oil or other hydrocarbons. as argued by Lovelock, when the extreme of CC happens, you can forget about farming in most places and synthetic food will be one out of very few other choices. in that sense, we've been burning our future food on a far greater scale than we've realized.

It may occur to oil producers that perhaps they should sell us some oil so they can get vitally needed food. And it may occur to us that perhaps we should sell them some food so that they will give us some oil. Somehow a "net export crisis" in oil, and a "net export crisis" in food can only go a certain distance before they cancel each other out...

One can hope. Except your post last week suggested that price elasticities of eating are far higher than that of driving....

And in case one of these weekends you are bored and don't have enough volunteer material or environmental/energy puzzles to crack, I wonder what the top 10 oil exporting nations look like in terms of food import/export? And the top 10 food exporting nations in terms of oil import/export. I would bet that the countries that REALLY need the food, have neither oil nor food...

The common theme in the two following articles is that countries are looking after the home team regarding food & energy supplies. I suppose the worst position to be in would be a large net food and energy importer. It would be interesting to look at the total current dollar value of food exports versus energy--especially oil--exports.

In reality, this is the problem that a lot of us are going to face. If you are not a food or energy producer, the key question to ask is what essential goods and/or services do you have to trade for food and energy?

ELM in Action: Keeping the home team supplied with energy

http://www.tehrantimes.com/index_View.asp?code=160987

Oil Ministry ready to weather frost

http://www.voanews.com/english/2008-01-11-voa10.cfm

Low Supplies, High Prices Cause Concern Among Asian Wheat Importers

By Naomi Martig

Hong Kong

11 January 2008

I think the new Russian and esp Chinese tariffs on grain exports are going to really affect the market this year. Chinese exports in particular were important to Korea and Japan. Bloomberg also notes it today, in a piece that implicates biofuels.

"Jan. 14 (Bloomberg) -- Corn rose to the highest ever in Chicago on speculation that global demand for feed and biofuel will exceed production for the seventh time in the past eight years."

"China, the biggest consumer of grain and oilseeds, on Jan. 1 implemented a 5 percent tax on corn, rice and soybean exports and a 20 percent levy on wheat. The government last month sought to slow price increases by selling grain from stockpiles and canceling tax rebates. The yuan rose to the highest since a peg to the dollar ended in July 2005.

``Overseas buyers are looking to source grain outside of China,'' Beal said. ``Only U.S. supplies are available until South America starts harvesting'' in March, Beal said."

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20602013&sid=alkz._RTuYLI&refer=c...

Early this year, soft white winter wheat, usually the cheapest of wheats, hit $13.05 a bu in Portland. Portland is a major terminal for Pacific Rim exports. Unfortunately, the story is now behind a paywall and I am quoting from a saved copy.

""It's about 95 percent sold in the Pacific Northwest," said Jon Sperl, grain division manager at Pendleton Grain Growers. "There's a few people holding onto some small quantities, just playing the game."

"It's an inelastic demand at this point," he said. "They just pay the price because they have to have the commodity."

Some exporters are having hard time, Sperl added, because they're selling wheat they haven't bought, then find out they can't buy it. Raleigh Curtis, general manager of Mid Columbia Producers Inc., a Sherman County cooperative, looked back a year ago. Soft white wheat was selling for $5 per bushel delivered to Portland.

"Today, we're at $13.05," he said.

With prices what they are and stocks in such short supply, Curtis said he wouldn't be surprised to see hoarding begin. Some people around the world may begin hanging onto their wheat for their own fundamental uses.

In this vast wheat-growing region, he said, it's hard to imagine but most of the world wheat producers farm about two acres and store their crop in buckets instead of silos.

"If some of those acres become unavailable, then this market could go," he said. "We could see $18-$20 wheat before we get into a new crop.

Curtis agreed with Sperl that 95 percent of the wheat in the Northwest has been sold."

The relationship becomes something like:

"If you want us to grow your food, you'd better make certain we have an adequate supply of oil..."

More succinctly

regards

As I said in previous posts, the rush to biofuels is not a US-only phenomenon. And I've just found a very good and up-to-date source of information on the global picture:

The Future of Biofuels: A Global Perspective

http://www.ers.usda.gov/AmberWaves/November07/Features/Biofuels.htm

Stuart,

I think the point that subsistance farming has an insulating effect is very important, but I also think that geopolitical considerations are even more important. Many of the places that are poor have large resources that are exploited through corruption. It is thought to be bad form to use food as a weapon, but the world seems perfectly happy to see it used as a bribe. I would expect that in a high grain price environment, we'll see governments willing to sign long term resource extraction contracts with countries that provide enough food aid to keep those governments from toppling. That will mean even higher food prices and the place where there is flexiblity is the ratio of pounds of livestock-to-pounds of people which is large in the US (about 6). The path of least resistance therefore would seem to be putting a large fraction of feedlots out of business. I think we will see China with many more resources locked in with the US shutout and US beef badly hurting, but not much in the way of starvation. Regulatory limits on the amount of ethanol produced from corn in the US is also a likely outcome though not soon enough to avoid the geopolitical shift this will cause. I once heard Bill Mollison make the very astute point that if you wanted to overcome the US, the cheapest way would be to buy our grain. He was thinking of loss of topsoil, but I expect that the present situation makes it even easier. If the price is right, we'll be willing to sell.

Chris

Hello SS,

Thxs again for your hard work. I think it would be interesting to know the prevalence of soil testing worldwide, and if it is low [as I suspect], how much NPK is being wasted to atmospheric outgassing and runoff into the oceans. The opposite corollary to this lack of soil testing would be reduced-from-optimal harvest yields due to Liebig Minimums; for example: a poor farmer may have overapplied N, but insufficient P--it is the overall balance that determines optimal harvest yields.

http://www.natchezdemocrat.com/news/2008/jan/13/area-farmers-feeling-inc...

---------------------------------

The public may be noticing that prices for many products seem to be on the rise, but many farmers are feeling the pinch when it comes to the cost of production.

Because the U.S. imports a lot of fertilizers, international incidents can also bring about an increase in prices.

“There was an incident in October where train derailed in Russia and that caused a disruption in Mississippi,” Oldham said. “We’re at the mercy of all these market forces that are happening in the bigger world.”

---------------------------------

The financial forces driving JIT agro-trends for seeds, NPK, pesticides & herbicides, and diesel is making us all walk the knife's edge on food supplies. I have posted earlier many links where farmers are on NPK allocation or having problems getting timely delivery of sufficient NPK quantities to synchronize with the seasonal planting cycles.

I echo Sharon's upthread comment that small garden plots may be a useful buffer to this trend, but only as long as the gardeners go mostly organic with composting. Having lots of people suddenly buying and hoarding industrial-NPK could instantly make the distribution problems much worse. It would not take much of a First World retail NPK purchase shift to instantly price a lot of Third World subsistence farmers out of the industrial NPK market.

Bob Shaw in Phx,Az Are Humans Smarter than Yeast?

I see that corn hit it's trading maximum allowable change today on news of less production and yield than initially reported AND increased demand next year.

I've simplified the values of corn (bushel) equivalent(from the price) to barrel of oil equivalent. Another way of expressing it is how many acres has to "produce" to buy a barrel of oil. Using the WTI spot price average for the calendar year (I've been lazy and haven't converted the oil cost to the corn seasonal year), we get the following comparisons:

No.of Bushels required for a barrel of oil: 23.7 bu/bbl

No.of acres required for a barrel of oil (figures in yield): 0.157 acres/bbl.

For comparison, in the late 1980's and through the 1990's it took between 5-8 bushels/bbl of oil. And although yields were lower, it took between 0.04 and 0.08 acres/bbl of oil during that same period.

It's one way to compare food for oil.

I'm thinking we need to switch cows to grass so we might at least eat some of our corn.

What's the difference between feeding corn to the chickens or feeding mash to the chickens?

Is it always fuel OR food or maybe fuel AND food.

BTW (and at risk of sounding extremely callous) does anyone know anything about the net efficiency of humans as a converter of food to physical work? Eg, if you have a certain quantity of corn or sugar cane, and you convert it to ethanol (with around 50% loss of the calories), and then burn the ethanol in an internal combustion engine, or in the alternative you feed the food to an unskilled human and then have them carry a load or a pull a rope, which gets more work done?

Stuart,

I think you can avoid callousness by asking about horse power. Looks like a horse, when it is working, gets about the same efficeincy as an ICE. So, with 8 hour days, you'd get about the same amount of work. I bet there is more recent data around somewhere. A resting horse burns 682 calories/hour, and a working horse about 4 times that.

Chris

Chris,

you might be wrong on this one. there are many reasons why LaoZi stated: 虚其心,强其骨,实其腹 - roughly translated - empty their minds, strengthen their bones and fill their stomachs. too much energy is wasted in the mostly useless or, often worse, trouble making brainpower of the mankind. and one might want to add: ware a hat! in average 60W is dissipated per head in cold climate.

Hay,

I actually meant horse power. My Amish neighbors use blinders to keep their horses' minds empty.

"We'll raise up our glasses against evil forces

Singing whiskey for my men, beer for my horses." --Toby Keith

Chris

Ahh.... the Matrix. The ultimate destiny of our species! ;-)

Very close call there stuart. Human efficiency is 40% at best. Usually less than that. Depends on the task of course. For example riding a well oiled bike is way more efficient than pulling a blcok of wood with a rope tied around it.

Average efficiency should be around 25% or so. Increases with fitness level.

On the other hand Gasoline burning engines are about 30% or so efficient. So 50% energy lost -when converting to ethanol and then 30% of that so we are talking about Humans doing better with 25% to 15%.

I searched the internet for some reasonable methodology to compute human efficiency relative to an internal combustion engine (ICE), however, I found nothing useful. So I'm going to invent my own comparison. See if you like it or not. I'm going to compare a tour de france (TdF) cyclist versus a car. (I'm intimately familiar with the energy inputs and outputs of a TdF cyclist, so that's why I'll pick it.)

So the typical cyclist will ride 200 km in roughly 5 hours and put out an average of roughly 250 - 300 W as measured by a hub-mounted powermeter. (Note, freewheeling is factored in there.) He needs to consume about 8000kcal a day to maintain his body mass, although it is common to loose a few kg's as the race progresses. It's really hard to factor in that loss with any accuracy, so I'll ignore it.

Our TdF cyclist's comparison is a sedentary human driving in a car, covering the same route as the TdF cyclist, and who consumes about 2000kcal per day to maintain his basic bodily functions. Thus the valid comparison involves the difference in energy intake (this is the energy going into useful work, not brain and organ function etc...). So our total energy input is 6000kcal.

Energy intake for the TdF cyclist = 6000kcal x 4 J/cal = 2.4x107J.

Useful work performed by TdF cyclist = 300W x 3600 sec/hour x 5 hours = 5.4x106J.

Efficiency e = W/Qin = 5.4x106J/2.4x107J = 0.225, or about 22.5%. This is about as good as the very best ICE.

Note, this has ignored the fact that a car drags around a ton of useless sheet metal in addition to the human occupant, but since you want a direct comparison of the engines, not the effectiveness of car transportation, this seems like a valid way to go. Conclusion: ICEs and humans are about equally matched.

I couldn't find anything useful either, which was why I asked. Your calculation is helpful. Let me alter it a bit for my purposes - I'm trying to figure out sort of the bottom line for unskilled labor versus machines in an energy/food constrained world. Is it going to make sense to (rapacious) business owners to replace unskilled labor with machines if either alternative has to be run from the food supply. So we have to include the basal metabolism since we can't get any work out of the human unless he/she is alive. And, the total power output will be lower for the average laborer than for an elite athlete. So perhaps we'd be looking at somewhere around 10%-15% efficiency.

Looks like ICE's are 20% efficient, but we also have to drop a factor of two for initial conversion of the food into ethanol. So we end up at 10% - about the same ballpark.

So it does look like energy efficiency of doing work is roughly comparable either way. Of course many other factors come into it - higher capital costs of the engine, but much higher power/weight, and power/volume.

Stuart, this doesn't address your question specifically, but perhaps gets at the point.

Are you familiar with the book Food, Energy and Society that was primarily edited and contributed by David Pimental? It basically examines different food production systems, from totally manual, to animal powered, to fully mechanized with oil, and the resulting calorie input:output ratios are.

The basic gist was that human-powered systems tended to have higher energetic profits than the animal-powered, which was higher still than the oil-powered.

Steve Moore is a farmer at a university in Virginia I believe and is going to publish a net energy study on manual cultivation soon. (It is in press or review in some journal). So you might want to check on his work.

Then there is the energy quality issue. A thousand gallons of refined gasoline probably has an order of magnitude higher quality than an equivalent throng of strapping, sweating workers, IF the fixed infrastructure is one that runs on gasoline.

If there is no fixed infrastructure, then the definition of quality changes, and gasoline wouldn't inherently be good for much more than fires or explosives. Its value is that the vast majority of our current fixed infrastructure runs on liquid fuels.

If you include basic bodily functions, 15% is probably about right. Just remember, power output != efficiency. I suspect the difference in efficiency between a well-trained amateur cyclist (e.g., myself) and a TdF cyclist is not actually that much, even though I lag somewhere between 50W - 100W behind in terms of my peak power output. It just takes me a lot longer to complete the same course.

As I recall, this very topic - how efficient humans are at converting energy - was discussed on TOD about summer 2006. I searched TOD but "human energy efficiency" or combinations thereof turn up too many hits.

It's pretty simple - when the machine can be fuelled more cheaply than the human for the same amount of work done, the machine will replace the human, and vice versa.

Because machines can do so much, fuel has to be pretty expensive before you shut down machines and replace them with people.

There's a reason that work like shipbreaking is done in low-wage countries like India and Bangladesh. It takes less people to do it in Belgium, but heaps more wages.

There are also many many jobs that take complex actions within which a human along with a relatively simple machine can outperform, economically at least, complex roboticized equipment. Look at all the sweatshops with vast banks of [relatively simple] sewing machines, each operated by a laborer paid pennies for wages. It is perfectly conceivable that equipment could be designed to automate most of this work. I suspect it isn't done mainly because of capital expenditure and, more importantly, lack of skilled labor to maintain the more complex machinery.

It's another one of those situations with a sigmoid curve. An optimal point is reached between use of human labor and the complexity of the equipment, skill of the labor, wage arbitrage, social conditions, etc. etc.

Trying to break the complexity of this difference down to joules per human vs joules per machine is IMO rather silly.

Agreed, maybe silly when you realize all the things that are being ignored. However, in order to make order of magnitude estimates and/or simple workable models of complex systems, it is necessary to make these silly assumptions and ignore the finer details. Those get added in as necessary.

Stuart, thanks for this incredibly important work.

A few comments on subsistence farming.

First, I think that there are a few places which will remain unscathed by these developments. Very few communties are divorced enough from the global money economy to be protected.

Here you have been trying to assess the globabl magnitude of the problem, but I feel that a closer look at specific countries and regions is necessary. Some may be more vulenerable than others. I will talk about the Middle East, which is my region and also I have been researching and writing about. In Egypt, for example, wheat is staple cereal, and Egypt imports 38% of its supply (see here). Somewhat sketchy data on poverty that I could find points to %25 urban poverty (under the 2$-a-day poverty line). This does not spell good. The Government and World Bank have been advocating a switch from cereals (wheat, rice) to cash crops as grapes, tomatoes, melons, and strawberries, for exports to Europe. This makes sense because these require less water (a big problem) but farmers have been reluctant, because they do not want to give up subsistence crops. For good reason...

Another factor, not easily calculable but important, is mutual support. In more traditional societes the networks of families/neighbourhood are much stronger and they allow them to endure hardship to a much greater extent. This, for example, is one of the reasons for why there is no famine in Gaza, despite almost two years of effective embargo (the only food imports are UN relief). However, one cannot generalise this phenomenon and it varies with culture, economic situation etc.