The Fallacy of Reversibility

Posted by Stuart Staniford on January 22, 2008 - 11:00am

Why Peak Oil Actually Helps Industrial Agriculture

Claas (Caterpillar) Lexion 570 combine harvester in action. Image courtesy: Wikipedia.

This argument has never really made sense to me, but my recent explorations of food prices and biofuels have sharpened up my conviction that the thinking behind this position is mistaken. In this piece, I'm going to first document that some influential peak-oilers do in fact believe this, then try to discuss what I think the reasoning is -- it's not usually made very explicit but it depends on something I'm calling the Fallacy of Reversibility. Finally, I'm going to lay out why I don't think things are going to go the way the proponents of relocalization expect, at least not any time soon.

Relocalization Quotes

The idea that "peak oil" was something that society was going to have to reckon with began amongst scientists with backgrounds in the oil industry - most famously Hubbert himself, and then elaborated by Colin Campbell, Jean Laherrere, Ken Deffeyes, and others.These oil industry scientists - what I will call the first wave of peak oil thinkers and writers - were mainly interested in estimating when peak oil would be, and the likely supply side mitigations (or lack of them). The implications of peak oil for agriculture was not a major focus. However, a second wave of journalists, writers, and non-profits have been doing a lot to spread the word about peak oil - Richard Heinberg, James Kunstler, Julian Darley and the Post Carbon Institute, the staff of the Community Solution, and others have all written books, held conferences, and started non-profits to warn the world about the dangers of peak oil. Given that the world as a whole has been doing its best to stay in denial about peak oil these outreach efforts have been a valuable service -- certainly I have learned a lot from them. At the same time, these writers bought to the table an agenda about society in general, and agriculture in particular, that I believe lacks an empirical foundation.

Let me start with a quote from Jim Kunstler:

We have to produce food differently. The ADM / Monsanto / Cargill model of industrial agribusiness is heading toward its Waterloo. As oil and gas deplete, we will be left with sterile soils and farming organized at an unworkable scale. Many lives will depend on our ability to fix this. Farming will soon return much closer to the center of American economic life. It will necessarily have to be done more locally, at a smaller-and-finer scale, and will require more human labor. The value-added activities associated with farming -- e.g. making products like cheese, wine, oils -- will also have to be done much more locally. This situation presents excellent business and vocational opportunities for America's young people (if they can unplug their Ipods long enough to pay attention.) It also presents huge problems in land-use reform. Not to mention the fact that the knowledge and skill for doing these things has to be painstakingly retrieved from the dumpster of history.The Community Solution also believes that the current agricultural model cannot be sustained, though they are concerned about the ability to manage the transition:

Reliance on large-scale agribusiness, driven by vast energy consumption, has resulted in an agricultural monoculture that is simply not sustainable. But where are the tens of millions of small farmers who will be necessary if we are to return to locally grown food crops? And what about all the food that is being used for feed, and now, for fuel?The Post Carbon Institute is attempting to build model farms of the kind that they believe will be required post peak:

Using science, proven tools, and evolving methodologies the Energy Farm Initiative seeks to demonstrate systems of agriculture that can sustain both farms and communities in the face of climate change and peak oil. This program weaves threads of the Relocalization vision into a fabric of local currency, local food and biofuel systems, revitalization of local industry, and community cooperation.Another writer who has been very influential in getting the word out about peak oil is Richard Heinberg (including reportedly reaching former President Bill Clinton). I profiled Richard here. In December of last year, he wrote:Our aim is to build flexible systems that reduce dependence on high energy inputs and produce food and reliable renewable energy for local users. The steps in which this transition is manifest is the Local Energy Farm Initiative.

The aim of substantially or entirely removing fossil fuels from agriculture is implicit in organic farming in all its various forms and permutations - including ecological agriculture, Biodynamics, Permaculture, Biointensive farming, and Natural Farming. All also have in common a prescription for the reduction or elimination of tillage, and the reduction or elimination of reliance on mechanized farm equipment. Nearly all of these systems rely on increased amounts of human labor, and on greater application of place-specific knowledge of soils, microorganisms, weather, water, and interactions between plants, animals, and humans...I have to say that I really don't like the sound of "at a forced pace, backed by the full resources of national governments". As JD, of Peak OIl Debunked, noted recently there is a history of attempts to forcibly reallocate land to urbanites: it's mainly been attempted by dictators, and the results have made the countries in question bywords of disaster (Cambodia and Zimbabwe are examples in recent decades).Because ecological organic farming methods are often dramatically more labor- and knowledge-intensive than industrial agriculture, their adoption will require an economic transformation of societies. The transition to a non-fossil-fuel food system will take time. Nearly every aspect of the process by which we feed ourselves must be redesigned. And, given the likelihood that global oil peak will occur soon, this transition must occur at a forced pace, backed by the full resources of national governments.

The most thoughtful advocate of relocalization I know is Jason Bradford, who is quantitative enough to have investigated his own area, the rural Northern California county of Mendocino, and discovered that the county probably could not feed itself:

Out of 2,246,400 acres of land in Mendocino County, 94,039 acres or 4.19 percent is considered prime agricultural soils (NRCS-USDA figures). Of that amount, much is unavailable and covered by roads, highways, cities, parks, and other land uses. While growth is very slow in Mendocino County, settlement patterns have tended to occur in areas dominated by prime soils. Only one third, or approximately 35,000 acres, of prime farmland remain available for agricultural use. Besides the unavailability of prime farmland, changes in hydrology as a result of agricultural and other human uses have affected the quality and use of prime farmland.I think as Jason investigates further, he is going to find more reasons for pessimism about this path.The Caltrans EIR implies that in about a ca. 20 year span, Mendocino County went from 69,000 to 35,000 acres of prime farmland, down from and original endowment of 94,000 acres. This does seem like a remarkably high rate of loss, totaling 34,000 acres or about 1700 acres per year for 20 years. In either case, whether the real figure is closer to 69,000 or 35,000, both are far from the estimated need of ca. 95,000.

The Fallacy of Reversibility

So, the second wave peak oil writers see us as abandoning the combine harvester and returning to this kind of scene:

Raking hay by hand. Image courtesy: University of Minnesota.

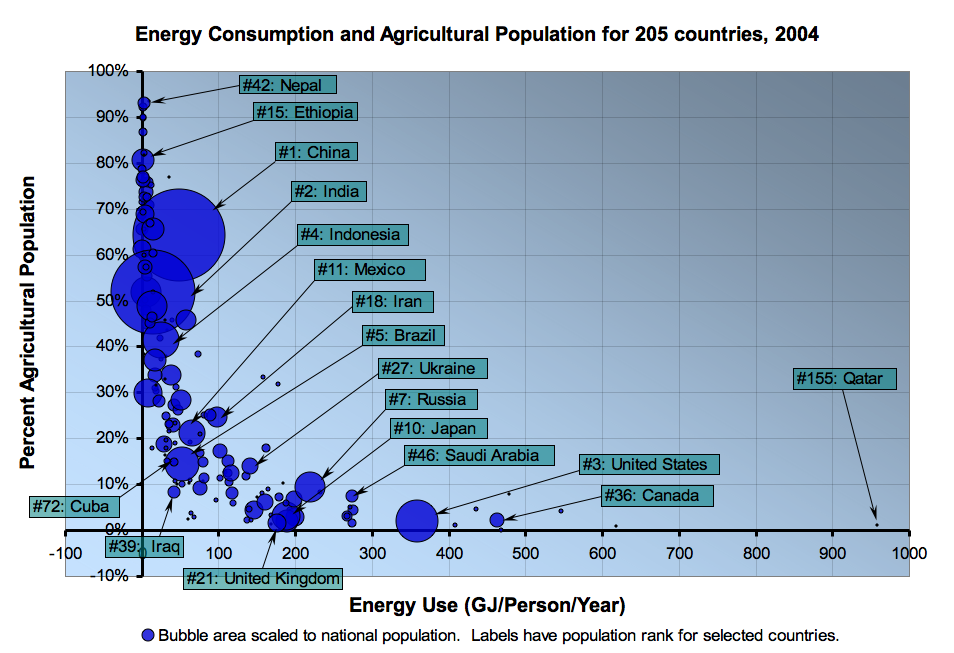

Let me try to summarize what I believe the underlying logic of their position is. What is certainly true is that pre-industrial societies generally use a lot less energy, and have a much larger share of their population involved in agriculture than industrialized societies do. Jason Bradford did a nice analysis a few weeks back, and I made this graph based on his analysis:

Clearly, as countries have gone through the process of industrialization and development (roughly moving down the curve to the right), they have come to use more energy in general, and their agriculture has become far more mechanized and involves a smaller fraction of the population.

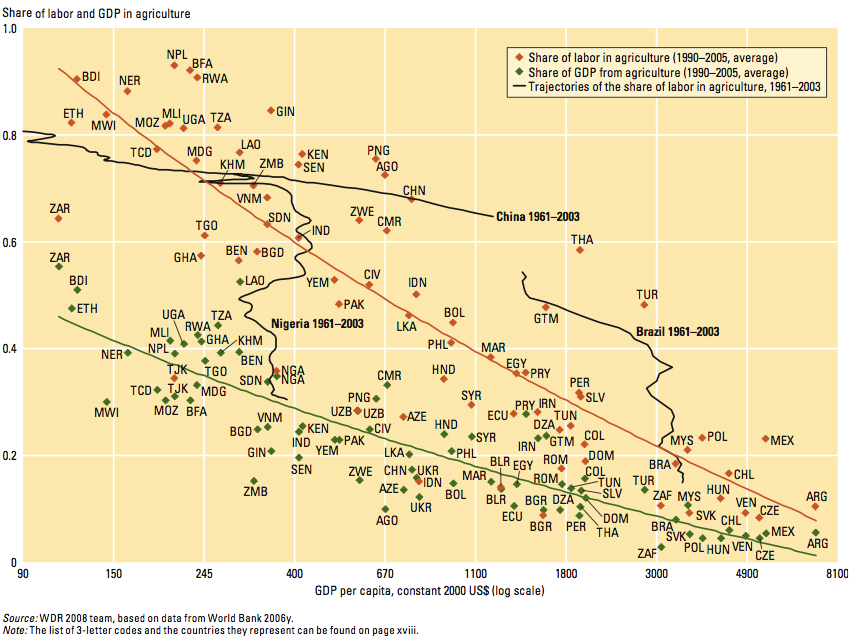

Another view of the same process can be seen in this World Bank graphic, which shows both the share of agriculture in the labor force and in gross domestic product, but this time plotted against GDP/capita:

This reminds us that countries that have far higher portions of the labor force in agriculture don't just use less energy, they are also far less wealthy. (Note that the scale in this graph is logarithmic and cuts off around Argentina - the full graph on a linear scale would have a sharply curved hyperbolic shape much like the energy versus agricultural population one from Jason's analysis).

So I think the argument of the relocalization advocates essentially is that, since we were using a lot less energy before we were industrialized, and our population was primarily agricultural then, and peak oil implies we will have less energy in the future, or at least less liquid fuel, then it must be the case that the agricultural population will grow again. In other words, having coming come down the curve in the graphs above from the top left to the lower right, our society will now start to retrace its steps back up the curve.

This implies that the process of industrialization and development is a reversible process. We in the developed world have evolved from low-energy high-agriculture societies into a high-energy low-agriculture society. So the thinking goes that we can/should/will reverse that process and go back to something like what we were 200 years ago (at least on these large macro-economic variables).

Now, coming from a background as a scientist, there are many reversible processes familiar in science (and indeed in everyday life), but there are also a lot of irreversible processes. Some examples of reversible processes - if you lift up a weight, you can set it back down again into the same position it was in before. If you blow up a balloon, then, up to a certain point, you can let the air out and get back more or less the uninflated balloon you had before you started. If you pump water from a lower reservoir to a higher reservoir, you can let it down again, and the lower reservoir will be in little different condition than if you hadn't bothered. If you freeze a liquid by cooling it, you can warm it up again and have the same liquid.

Here are some examples of irreversible processes. If you let grape juice ferment into wine, there's no way to get grape juice back. If you bake a cake in the oven, there's no way to turn it back into cake dough. If you ice and decorate the cake, but then accidentally drop it on the floor, there's no way to pick it up and have anything approaching the same cake as if you hadn't dropped it.

So when you industrialize a society, is that a reversible process? Can you take it on a backward path to a deindustrialized society that looks in the important ways like the society you had before the industrialization? As far as I can see, the "second wave" peak oil writers treat it as fairly obvious that this is both possible and desirable. It appears to me that it is neither possible or desirable, but at a minimum, someone arguing for it should seriously address the question. And it is this failure that I am calling the Fallacy of Reversibility. It is most pronounced in Kunstler, who in addition to believing we need a much higher level of involvement in agriculture also wants railways, canals, and sailing ships back, and is a strong proponent of nineteenth century urban forms.

I am going to christen this general faction of the peak oil community reversalists. This encompasses people advocating a return to earlier food growing or distribution practices (the local food movement), folks wanting to bring back the railways and tramcars, people believing that large scale corporations will all collapse, that the Internet will fail and we need to "make our own music and our own drama down the road. We're going to need playhouses and live performance halls. We're going to need violin and banjo players and playwrights and scenery-makers, and singers."

And before moving on, I stress that I'm not making an argument that our time is in all ways better than earlier times and that nostalgia for the past is entirely misplaced. Nor am I making an argument that peak oil does not pose a massive and important challenge to us. Instead, I'm making an argument that society is unlikely to reverse its trajectory of development, regardless of what we might like. Calls for it to do so are a distraction and get in the way of figuring out what we really need to be doing, and what the real options and dangers are.

Why it Won't Be So

Although the reversalist approach to peak oil covers many dimensions of society, I'm going to confine my attention in this piece to the proposition that agriculture is likely to revert to eighteenth or nineteenth century approaches in the face of a slowly contracting oil supply. My central tool for looking at the question is going to be the factors going into the profitability of industrial agriculture. If it's the case that agriculture is going to revert to a manual low-energy process in the face of peak oil, then that should show up in the profitability data. Here are some natural predictions we might make:- Industrial farming is less profitable at high oil prices than at low oil prices.

- Now that we are at, or close to, peak oil, industrial agriculture is beginning to show signs of strain, indicating it may break down in the future, allowing alternative approaches to take over.

- Industrial farmers use more labor in the face of high oil prices.

- Farms are starting to get smaller now that peak oil is nigh.

- In developing countries, where the farmers never unlocalized in the first place, the dynamics are changing to favor small subsistence farmers over larger mechanized operations.

Agricultural Profitability and Oil Prices

Most of my analysis is based on the data compiled by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) on the average costs of growing various kinds of crops. This data is based on national surveys of farmers and represent an average for all farmers (some will be doing better than the average, some worse). Let's start with corn:

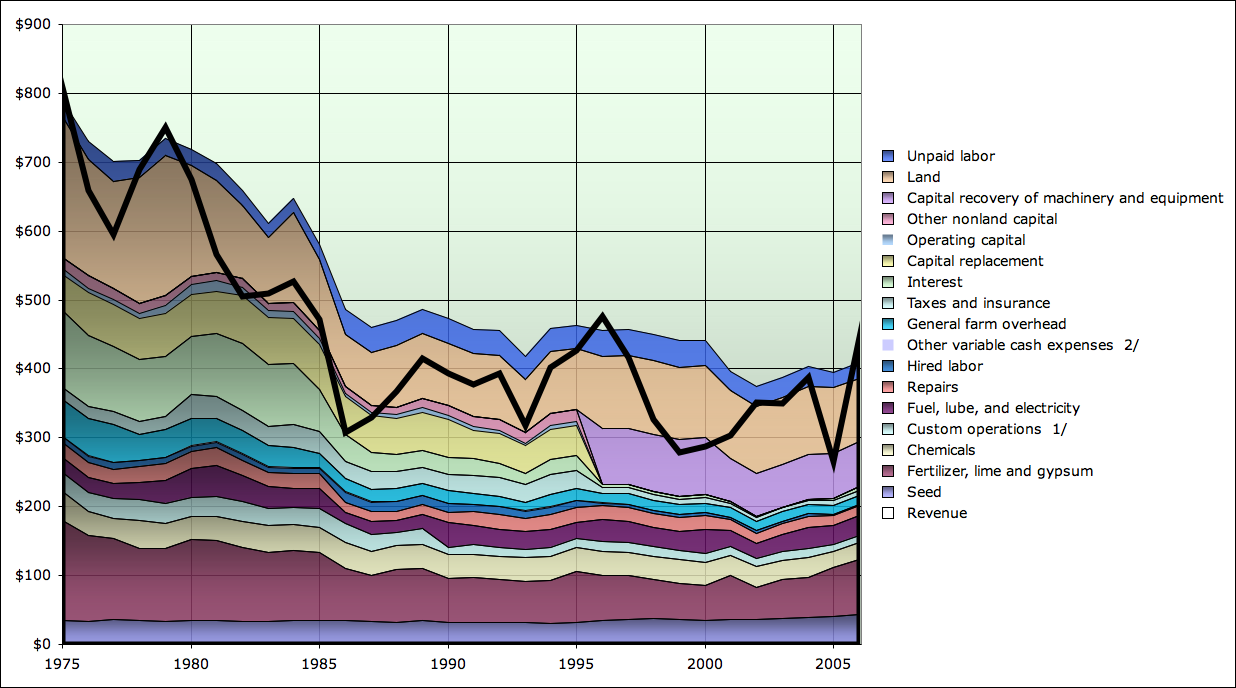

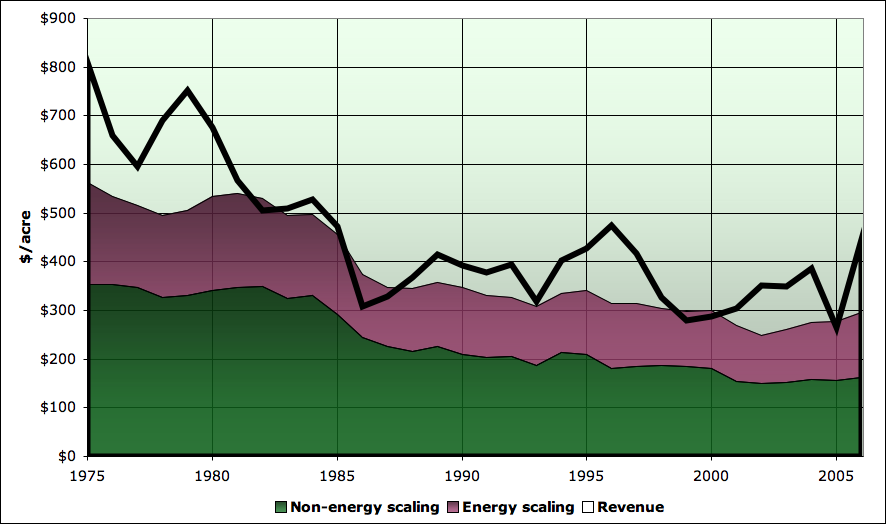

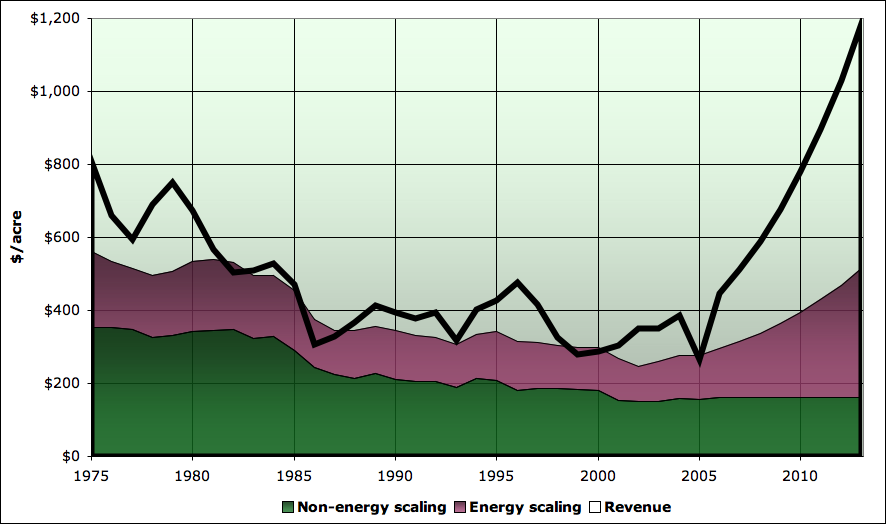

Average cost structure and revenue of US corn farmers, per acre, 1975-2006. Source: USDA. Costs have been adjusted to 2006 dollars via the BLS CPI-U.

Here, the various colored bands are the different costs of producing corn, expressed in 2006 US dollars per acre of land planted in corn. The heavy black line is the revenue per acre of selling the corn. The big picture is that very little money is spent on labor (indeed, agriculture in the US is highly industrialized), that costs have been coming down over time, and that farming in recent decades has been an activity with modest and unpredictable profits (that graph represents a business I would not want to be in). The cost reduction per acre is particularly striking given that yields per acre have been improving steadily over this period - farmers have obviously gotten enormously more productive over time (all that machinery and those fancy chemicals really do work as advertised, it seems).

It's worth quickly noting that most of the spikes of better profitability come at times of high oil prices (1975, 1979, and 2006). We will explore this more systematically in a moment.

Here is the same thing for wheat:

Average cost structure and revenue of US wheat farmers, per acre, 1975-2006. Source: USDA. Costs have been adjusted to 2006 dollars via the BLS CPI-U.

The story is similar, except that both costs and revenues per acre are lower, and profitability is even worse.

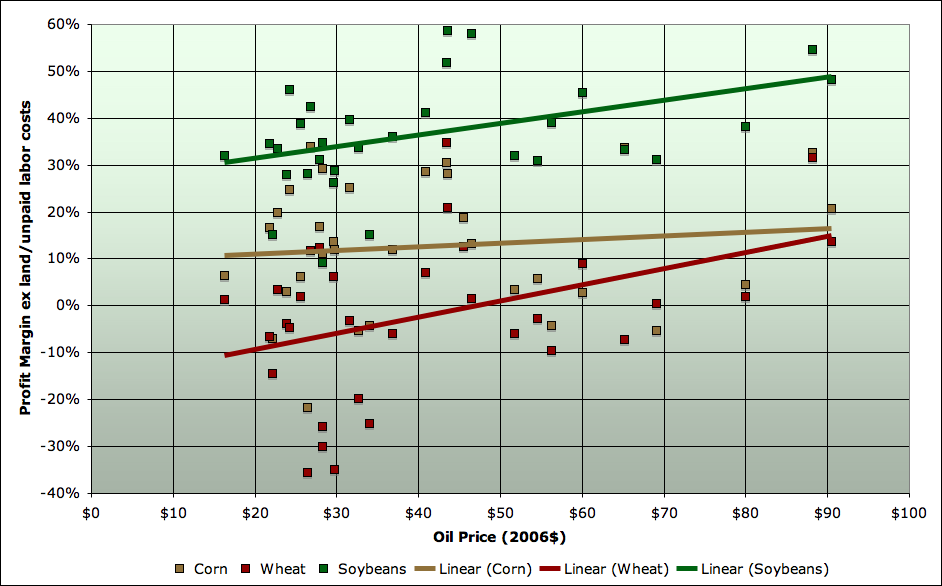

To look at the relationship between profitability and oil prices for the sectors as a whole, I took the profit margin (revenues - costs)/revenues, but excluded land and unpaid labor from the costs. The reason for excluding land is that I would expect land prices to mainly reflect the profits being made on the land, so including them in costs is confounding understanding the profitability of the sector (obviously, an individual farm has to worry about the land costs, but the land is only worth anything because people are farming it, so it's a confounding effect at at sector level). I excluded unpaid labor as owner's compensation which I consider more a form of profit than a cost. For that definition of profit margin, for the three main arable field crops, we get this graph:

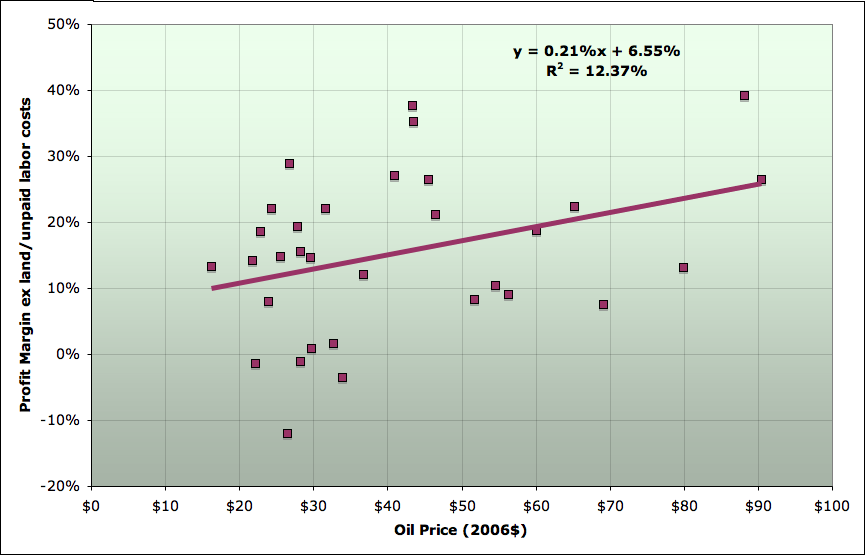

Average profit margin for US farmers on three main field crops, versus oil prices. Profit margin is computed without the land rent or unpaid labor cost components, 1975-2006. Source: USDA and author's calculations for profit margin, BP for oil prices in 2006 dollars.

There is a very weak upward slope to all three lines (ie in the direction of better profits at higher oil prices). In an effort to reduce the noise, I produced a weighted average according to the planted acreage of the three crops:

Acreage of three main field crops in the United States, 1975-2007. Source: USDA.

and thus got this graph:

Average profit margin for US farmers on acreage weighted average of three main field crops, versus oil prices. Profit margin is computed without the land rent or unpaid labor cost components, 1975-2006. Source: USDA and author's calculations for profit margin, BP for oil prices in 2006 dollars

The relationship is somewhat stronger - profits are a little likelier to be higher when oil is expensive, but oil prices explain only about 12% of the variance in profit margins. The relationship is just barely statistically significant (p = 4.9%), but I wouldn't set too much store in it, given that the regression is not controlled for any other factors that might be explanatory.

But certainly, there is no evidence for the idea that farms are less profitable at high oil prices - that inference is completely unsupported by the data since 1975.

The analysis does not include 2007, since the cost data are not available yet, but it is likely that 2007 had high profit margins (since crop prices were very high), and certainly it had fairly high oil prices. I will argue below that this is a harbinger of the game-changing role of biofuels, which will tend in the future to make industrial farming more profitable as oil prices rise.

Labor Usage in Arable Crop Production

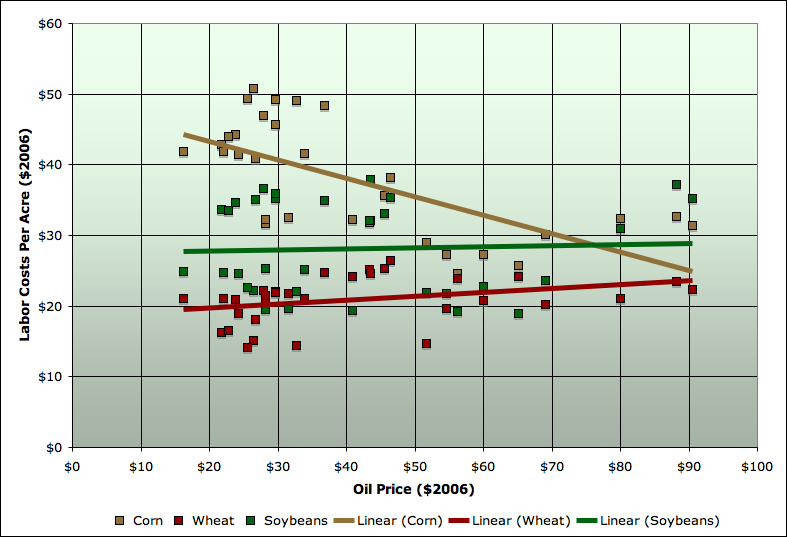

Let's turn for a moment to the use of labor in the farm system. If it was the case that peak oil was promoting a return to a more local, less industrialized, style of agriculture, we might expect to see usage of labor correlated with oil prices - when oil prices are high, farmers are differentially likely to prefer to do things manually and use less expensive fuel to get the job done. So I looked at the total labor input (both paid and unpaid) into the crop versus oil prices:

Average labor expended per acre by US farmers of corn, wheat, and soybeans, versus oil prices 1975-2006. Both are converted to 2006$. Source: USDA.

What we see is that wheat and soybeans show essentially no meaningful relationship between oil prices and the amount of labor per acre that farmers use. They use the same low amount regardless. Corn farmers actually spend less on labor when oil prices are high, for reasons that are unclear - however the relationship is quite strong (r2 of 43%) and very statistically significant (p = 0.005%).

So again, there is no evidence in the data for the reversalist idea that farmers might need more labor when oil prices get high on account of peak oil.

Biofuels and the Future of Industrial Agriculture

A possible objection to my argument thus far is that, although we may be at or near peak oil, nonetheless we haven't seen anything yet in terms of how high oil prices could go - $100/barrel is nothing, and when we see $200/barrel or $300/barrel, then the situation will change, industrial agriculture will fall apart, and the reversalist future (which is really the past) will start to play out.Now, I certainly would not discount the possibility that oil could get to $200/barrel. With an income elasticity near 1, we would expect to see oil usage expand by a few percent a year due to global economic growth if prices were constant. Since supply has not been increasing at all for the last couple of years, higher prices have been required to balance supply and demand. Since elasticity of oil demand is more like 0.05, it takes several tens of percent of price increases each year to balance the missing single percentage point increases in supply that aren't occuring. That's how we got to $100 oil. If supply continues to be flat, it's quite possible oil will get to $200 in a few years time. On the other hand, if the credit-collapse recession in the US turns severe, as it certainly could, oil prices could fall a lot instead. If we do manage to get a boost in supply from the 2008 megaprojects, that will moderate prices also, at least for a time.

But what I would argue is that if oil gets to $200/barrel, industrial agriculture is likely to do very well. I pointed out in Fermenting the Food Supply that corn-ethanol has been profitable even without subsidies at times in the last few years, and that whenever oil prices go up sharply, there is a huge spurt in the growth of the biofuel industry. This creates an arbitrage between food prices and fuel prices, and mean that the former must go up whenever the latter go up (since the biofuel industry can very easily use most of the global food supply without adding more than a modest fraction to the fuel supply). This next graphic summarized the key point:

Bottom panel: capacity of ethanol plants at year end, in production and under construction, as a percentage of total ethanol potential of the entire US corn crop in that year (left scale), together with year on year change in that percentage (right scale). Top panel: oil prices (annual average in $2006). Sources: USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service for corn production, National Corn Growers Association for conversion efficiencies, and Renewable Fuels Association for ethanol plant capacities. Oil prices are sourced from BP.

I suggested earlier that the growth rate has a lot to do with oil prices, and I've made that more explicit in the graph above with the green lines. When oil prices spike up, a year or so later we have a new burst of ethanol capacity under construction (which then comes on stream 1-2 years after that).This has had a lot to do with the high crop prices of the last two years. Thus, if we get $200 oil, I confidently expect a new burst of growth in crop prices and for farm revenues to go up a lot. If we look at the average costs over the last thirty years:

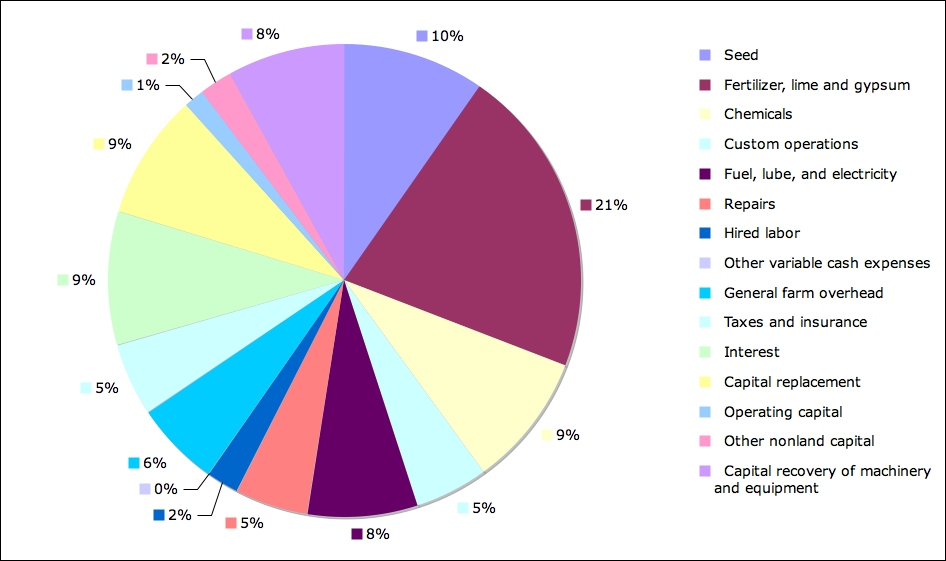

Average cost structure and revenue of US corn farmers, per acre, 1975-2006. Source: USDA.

we can see that some costs are of a kind that scale with energy prices. The "fuel" component is certainly that way, but fertilizer is almost entirely made from natural gas and will tend to go up in periods of high energy prices. And, for safety, I've also included chemicals, most of which have petroleum or natural gas as the feedstock (though I imagine most of the value is added in manufacturing, rather than in the raw fossil fuel input). However, the rest of the farm costs don't have a direct relationship to energy costs (the various forms of labor, cost of capital, etc). So with this decomposition, the history of corn farm costs and profits looks as follows:

Revenue of corn farmers, together with cost structure decomposed into hypothesized energy price scaling and energy price independent components . Costs exclude the land rent or unpaid labor cost components, 1975-2006. Source: USDA.

As you can see, the non-energy components have not increased much at all since 2002, but the energy-related portions have been increasing sharply. All costs were high in the 1970s and early 1980s (when not only were energy costs high but interest rates were extremely high too, so that capital costs were very great).

So going forward, I expect to see significant increases in food prices and farm profitability (with a significant caveat for the possibility of a credit-induced severe recession). The following hypothetical scenario for what happens to the corn curve if both energy and corn prices increase by 15%/year in real terms, while other farm costs (eg labor, cost of capital) stay flat in real terms. As you can see - industrial farmers do very well in that case:

Revenue of corn farmers, together with cost structure decomposed into hypothesized energy price scaling and energy price independent components . Costs exclude the land rent or unpaid labor cost components. Actuals for 1975-2006, and scenario (not forecast) for 2007-2013 based on 15% annual increases in energy-scaling costs and corn prices, with flat other costs. Source: USDA.

Clearly, farmers making money like that will not be selling out to hordes of the urban poor trying to go back to the land, nor will they need to employ them. Instead, the farmers will simply outbid the urban poor for the energy required to operate the farms (and in the US, the farm sector only uses 2.2% of all petroleum in the country).

Farm Size Trends

Farms in the US have been getting steadily bigger for a long time. The reasons are very simple: there are substantial economies of scale in industrial farming - it's desirable to keep the expensive machinery and administrative labor working at maximum capacity, which means spreading it out over as much land as possible. That leads to this kind of graph:

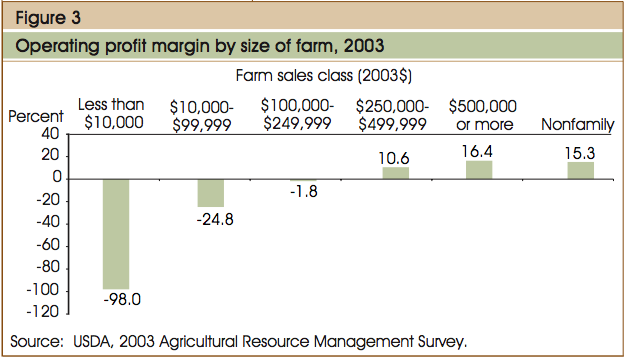

Operating profit as a function of farm size in the US, 2003. Source: USDA.

Small farms lose money at a great rate, and only large operations make a profit. This is a recipe for larger farms as the small ones sell out to their wealthier neighbors. As the share of energy in the cost structure grows, this graph may moderate a little (since fertilizer and fuel usage are likely directly proportional to acreage). However, there is nothing in high energy costs that will make it reverse - it will still be beneficial to spread the non-energy costs over more acreage. Thus although the trend of increasing farm size may slow, there is nothing to put it into reverse.

And in the developing world, another important factor comes into play. As we discussed last week, over half of all households in rural areas in developing countries are net food importers, even though the vast majority are involved in agriculture somehow. Thus, rising food prices will place tremendous stress on very poor households that grow some food, but not enough to live on. They may be forced to sell their land to larger landholders that produce a surplus. Thus, we may see the exact opposite of what the relocalization movement might predict - farm sizes in developing countries may increase in the face of peak oil.

In Conclusion

I've argued in this piece that industrial agriculture is likely to be stronger and more profitable when oil prices are high, not weaker. So the reversalist future of local food production on smaller farms with higher labor input will not come to pass as a result of peak oil. The industrial agricultural sector owns most of the land, and will be in an excellent position to increase their land holdings as remaining subsistence farmers fail or consolidate in the face of high food prices. Industrial farmers will have no reason to sell out to improverished urban dwellers. Thus the industrialization of the land is not a reversible process any time soon - it is a fallacy to think so. The reversalists are expressing wishful thinking and nostalgia for the past, not a reasoned analysis of how the future is likely to play out. And urbanites worried about their future should not be looking to buy or rent a smallholding as a solution to their problems - industrial farmers are extremely efficient, and there is no way to compete with them except by becoming one.

Selected Food, Agriculture, and Biofuel Articles at The Oil Drum

Stuart Staniford

- Death Rates and Food Prices

- Fermenting the Food Supply

- Food Price Inflation

- Global Land Use

- Will biofuels always be hopeless?

Jason Bradford

Robert Rapier

- A Debate Proposal for the Ethanol Lobby - Let's Get It On

- Mythbusters: Ethanol and Foreign Oil Displacement

The ELP Plan: Economize; Localize & Produce

IMO, we are headed for the never ending boom/crisis in the food and energy sectors. Whether it is a boom or a crisis for a specific person is largely dependent on whether or not you are involved in something related to food and/or energy production.

Regarding the Electrification Of Transportation (EOT) movement, it’s interesting to compare total energy consumption in the EU versus US (the EU uses about half as much energy per person as the US). Of course, this is also related to their high energy consumption taxes. However, I suspect that very few people would now argue that the US system is superior. The other question is whether we can go back to what we once had and what the EU now has, regarding EOT. As Alan Drake has pointed out, we did it before in the US, with minimal fossil fuel input.

Regarding the larger topic of farming, it seems to me that the obvious comparison is the small Amish farm versus industrialized farming. My recollection is that the yield per acre on Amish farms is lower than industrialized farms, but the profit per acre is higher.

http://www.landinstitute.org/vnews/display.v/ART/2000/12/15/3df6412ab088c

An economic comparison of traditional and conventional agricultural systems at a county level

M.H. Bender

Accepted December 15, 2000

Thanks for this lead Jeffrey. One of my concerns has been the reliability of a lot of common statistics gathered by the government. It is very difficult to find comparison data on different scales and methods of production because alternatives to the industrial ag model are relatively scarce in the U.S. and those who pursue them do so in a kind of parallel universe with their own norms of communication. I simply don't know if they are even on the radar screen when looking at USDA census data.

Jason,

One book you might get ahold of is Traditional American Farming Techniques, ISBN 1-58574-412-3, Lynons Press. It's a reprint of a 1919 (IIRC) farm book, 1086 pages. I highly recommend it. It has a lot of good information on "farming" including such things as horse "efficiency." Essentially, there are certain sized farms that use horses more efficiently. If you get up my way, I'd be glad to loan it to you. I'm in the phone book.

Todd

PS The Garden Club is still screwing around in setting up a Terra Preta presentation.

Todd, you recommended the book a week or so ago and I purchased it online from Deepdiscount. It is amazing the breadth of knowledge agriculturalists had at that time, especially in regards to soil management and cover crops such as alfalfa and clover. For someone like me who has a small farmette, it will be very useful. I’ve been browsing through it for the last week.

I too ordered it a few weeks back when Todd recommended it. Its a thick bugger and I've had trouble keeping it out of my fathers mitts. Much of it over my head, but I guess thats the point of ordering it.

I just ordered it also. Thanks for the tip.

Stuart is probably correct about the continuing growth of industrial agriculture. The merging of the energy markets with the food markets means that the price of both shall move upwards in lockstep. Both our engines and our bellies will face progressive starvation.

This is even now being played out in the third world. Their farms are industrializing and growing food, fiber and energy for export, leaving the billions living on less than $5 a day to be priced out, with little chance of gaining access to cultivable land.

There are several questions: will those hundreds of millions quietly starve? At what point will there be revolution? What form will that revolution take; nihilism and suicide vests? retro Maoism?

I suspect that, at least in the first world, massive bankruptcy, combined with massive foreclosures and rising food and energy prices, will force democracies to turn to increased redistributionist policies, protectionism, and possibly fascism.

I could be mistaken but I think that revolutions are started by the middle class with input from guilt ridden or disaffected uppers. The poor pick up the torch a bit later as they are more likely concerned with finding the next meal.

I believe you are right.

Actually, revolutions are often started by first world elements within third world countries (Lenin & Mao, Pol Pot, and Sindero Luminoso in Peru; western educated/influenced leaders leading largely uneducated workers and peasants). But revolutions can also be started by reactionary third world leaders like Ayatollah Khomanei.

As Stuart's analysis sinks in, I realize this is the worst news I've heard in a long time.

Agribusiness -- a product of the "age of oil", -- has been primarily concerned with producing food and fiber. It dominates the best soils in the world, and is still in the process of displacing traditional farmers.

If the food markets hadn't merged with the energy markets, we would expect that we would now be experiencing "peak agriculture" along with "peak food". This (hopefully) gentle decline would give societies time to convert to whatever replaces agribusiness.

Instead, agribusiness is switching to producing motor fuels, so "Peak Agriculture" is now divorced from "peak food."

As agribusiness increasingly grows biofuels for our vehicles, it profits even as it diverts land and energy away from feeding people. Thus, peak agriculture is a long way in the future, while peak food is now, with a vengeance.

Furthermore, as we look at Hubbert's curve as it descends into the Oldavai Gorge, we are right to wonder at what point industrial agriculture no longer functions properly.

Can steel for tractors and combines be smelted using renewable energy? Can fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides compete with ethanol and biodiesel? If they cannot, then it is difficult to see industrial agriculture surviving beyond mid-century. And if it continues to grow up to the end, we may see a spectacular crash.

Meanwhile, of course, we can project that global famine is coming on like a freight train.

I've got serious doubts as to whether we'll see the current corn-based industrial agriculture continue as far as midcentury in much of the US. Many areas depend on nonrenewable aquifers for their irrigation, and have only a 20-25 supply of water remaining. We're going to run out of water long before fossil fuel limitations seriously constrain American agriculture.

Depending on how we use the last few years worth of it, we will either transition to some sort of available-rainfall based agriculture in much of the midwest, or experience another dustbowl.

..or you could charge properly for water, and use some of the many conservation techniques available, such as are common practise in Israel, for example.

Conservation would slow the depletion rate, but not solve the problem that we're trying to irrigate with a nonrenewable source of water. Even if we launch a massive conservation effort next year (which realistically, isn't going to happen) we will likely see exhaustion of several major aquifers within my lifetime.

We can smelt metals with nuclear, wind, solar, geothermal power.

Whether this trend is bad news for you personally depends on your income level. With a high enough income you'll be able to buy more expensive food and put more expensive biodiesel in your gas tank.

But is competition for agricultural product between food and biofuels really the worst possibility here? Seems to me not. What would be far worse is if agriculture has a very low EROEI. Take away the oil and we have a hard time running agriculture if that is the case.

By contrast, with a high EROEI from agriculture while part of the agriculture will get shifted to producing energy at least the remaining part that produces food has energy from its own fields to power it. I find that comforting. I just have to earn enough money to afford to buy the resulting product.

So you and me and 100 million others can afford food on the table. The other 6.4 billion (plus interest) can all go to hell.

I wonder if those "others" will let me enjoy my meals in peace....

Yes, at least on a small scale. CSP arrays can produce a lot of heat, or a large WT array could produce a lot of electricity for an electric furnace; maybe both could be combined. It might be possible (indeed, we DO have to figure out how to MAKE it possible) to set up sufficient capacity to recycle metals from old worn out equipment in order to make new equipment.

If we can't manage this, then sooner or later we will fall all the way back in the neolithic.

Hi Todd,

Just ordered it. Thanks! As a newbie to farming I appreciate good leads.

I don't have any idea what your last name is, but know another farmer around here who wants to talk to you. Would love to go to a Terra Preta presentation so please let it be known in Willits when it is happening.

You do know my first and last name and I am in the book too...or contact the WELL office to get a message to me.

Jason, I think this is a very good point. And we are that particular case in point. We just purchased 13 acres of "black dirt" muck soils 60 miles from New York City. This is soil that is only allowed for farming and not development because of its particular geological formation and lack of suitability for a septic system.

Most farms are large enough, 75 acres and up, to qualify for government support and protection and therefore must "register" with the USDA. Because we are so small, we don't qualify for the government programs and are therefore "unregistered."

I know of several other farms who are in the same category. One is owned by a man from Bangladesh who farms 15 acres planting just two crops of which he saves his own seeds. He sells his produce on the street in Queens. In the winter he farms in Florida and ships his produce to New York. He is definitely not on the USDA radar screen. Another is a couple who grows 3 acres of vegetables and herbs in their backyard and sells via a farm stand by their house and a 25-member CSA -- also "unregistered."

Many of the farms who are traditional "onion" farmers (25% of US onions are grown here in Orange County, NY) are now diversifying into vegetables and selling via Farmer's Markets, farm stands and CSA because they can make more money on fewer acres in a more satisfying way.

This is interesting. I just started a new, very little farm, and know that my little operation is off the radar for USDA and suspected it might be the case for others.

You can register via the ag census, which is due soon:

http://www.agcensus.usda.gov/Help/Report_Form_&_Instructions/2007_Report...

Farms that get government assistance or have submitted this in the past automatically receive a form in the mail. Otherwise, you have to know about it. And as you say, small farms might not be eligible for the subsidies and so aren't in the loop.

Hello westexas,

A good friend of mine sells seed in extreme Southeast MN. Lots of Amish there.

This year they are RENTING OUT THERE FARMS.

Higher grain prices mean HIGH cash rent.

The Amish can currently make more money renting out their land to a real farmer than they can by farming it themself.

As profits on the farm rise with Peak Oil, the efficient operators will BID HARDER than ever for land. Inefficient operators (Amish) will increasingly rent their land to them.

The Amish of SE MN switched to making furniture.

Hi there Farmer, I rent out my money so I can do the things I feel are valuable to do, painting, music, gardening. That doesn't mean that I wouldn't make more money using it myself, it just means I value things other than money. Maybe the Amish just prefer to do more cabinetry which as far as I know is not something they just 'switched' to.

It really is sad to see what we have done to this world in the name of efficiency and greed rather than what we could have done in joy.

My apologies for moving upthread...

Stuart, as always, very impressive stuff. If you will remember "The Tragedy of the Commons", in capitalist societies land, over time, usually winds up in the hands a few families and due to our tradition (from English common law) of marriage and inheritance tends to stay there. Hence, property taxes were conceived of as a vehicle to force turnover of unused and unproductive land. Rising food and agricultural prices would certainly benefit those already entrenched in the endeavor. However, if food prices continued to rise in excess of the local GDP and inflation rate the price would eventually reach a point of no return, impossible to afford. Of course, this cannot happen in rational and free markets. If wheat and/or corn rose to $50, $75,$100 per bushel and animal flesh rose to $50 per lbs, the consumer would react. Front lawns and back yards would cease to exist, crop production would occur, co-ops would be formed, and entrepreneurship would flourish, much to the chagrin of the "second wave' folks, Kuntsler, et al.

The "consumer" would also react in other ways. They would be thinner. They would have fewer children. During this time the world would continue to slip further down the backside of bell chart. During the Great Depression we had no shortage of Farmland, oil, or labor, and we had far less than half of today's mouths to feed. Yet food was prohibitively expensive.

The "Second Wavers" for the most part are not only lacking in any economic training, they are colored politically, and seem to see things through the shaded lens of their politics. But I would not count on Industrial Ag to continue to provide incredibly cheap food - and therein lies the rub. To ever more expensive food prices, what will the social, economic, and political reaction be? Political science is not my strong suit, but it would seem that THAT is the devil in THIS detail.

Er, I thought this was exactly what the second wave folks were predicting? A mass movement back toward producing our own food? This is exactly what happened in Cuba, although there situation is different than what is likely to happen in peak oil: Cuba had an instant dropoff in fossil fuels, while the during peak oil we can expect a slow decline.

When we had minimal fossil fuels we had a much smaller population. We need high yield farms to feed a much larger population.

If large scale mechanized agriculture does not have a high EROEI then we are going to get awfully hungry. My hope is that the EROEI of farms is already high enough or will rise fast enough due to technological advances that large scale mechanized agriculture will survive. I think every rational person should hope for this.

Thanks for the in depth research on this topic. Though I agree with the general concept that industrial ag. will not be felled by higher oil prices, and in fact it may flourish...I think you are ignoring the potential for discontinuities, such as shortages of fertilizer and oil for processing and distribution. The shift that new line Peak Oil thinkers are talking about involve this larger scale discontinuity where oil (and nat. gas) is not just expensive, it is potentially scarce.

So though you may be correct in the short term, I wonder about your prognostications after a decade or two of depletion...

I agree that we need to consider the discontinuities.

You only need to look at the current situation in South Africa, where large industrial agriculture is encountering (previously rare) power blackouts. This leads to spoilt fruit and milk that can not be cooled, cows that can not be milked, and tends to bunch up other usage, such as irrigation, into large power-demand spikes taxing an already precarious grid. Farmers are coping in the short term by installing generators. It would be interesting to look at South Africa after another year of this to for trends against big farming or for small farming.

Francois.

I, too agree about the discontinuities. I was, in fact, surprised as I was reading the piece, which otherwise appears thorough and well-argued, because it failed to include this most basic of the assumptions of a world with reducing energy availability: systemic collapse or disequilibrium.

If one is talking about a period of transition from one primary energy source to another which is roughly stable, Stuart's argument may hold. It might be possible to transition and the primary forces might end up being economic ones. But that is ignoring the basic premise of those he is critiquing, that severe disruptions to the economic, financial and social systems will occur if Peak Oil occurs too fast or to abruptly for adaptation.

Further, the idea of "going back" isn't necessarily an accurate reflection of many people's views. I, for one, see the collapse of institutions and social structures as a positive sign not because I love anarchy, but because I believe we can maintain some of the core infrastructure and social fab5ric while transitioning to a holistic lifestyle that uses technology to create synergy with, rather than separation from, nature. In a simplistic example, the Enertia and Earthship homes come to mind.

Cheers

I have a deep respect for Stuart's line of thinking and have been struggling with understanding barriers to reversibility for a few months now. I think Stuart is correct that there are philosophical reasons behind promoting what he terms reversibility, but they involve much more than just the notion that energy decline will force the shift. Even though Stuart may be correct that short-term economic forces may promote further consolidation and industrialization of agriculture I view this as totally disastrous for the following reasons. (I also realize there is a big distinction between what I want to happen and what is likely to happen!)

Other reasons include:

1. Food security and system shocks (as noted above); better to build resilient alternatives ahead of time.

2. Top soil depletion. Soil biology is killed by chemicals fertilizers; for example, ammonia injections cause soil sterilization, followed by a bacterial bloom as highly soluble nitrogen becomes available, which then leads to a consumption of soil organic matter by the bacteria, which causes soils to compact, loose tilth, be more subject to erosion, etc. I suppose it is possible to disentangle industrial production methods from soil-killing methods, but big ag corporations are tending to promote their products, whereas the local and organic crowd has a better grasp on soil biology.

3. The Phosphorus (and other nutrient) cycle. Food and dry matter (e.g., straw) contains mineral wealth mined by the nanotechnology of root systems and incorporated into above ground biomass. Removal of these minerals depletes the soil. Industrial agriculture allows a huge geographic disconnect between production landscapes and consumer populations. Ultimately, the biological waste-stream of the consumer population needs to be returned to the productive soil ecosystems. Anything else is unsustainable and will lead to famine in the long run.

4. Climate change. We should be looking for ways to use soils to store carbon. Agriculture should be a net carbon sink, not a source. Finding the tool sets that are labor efficient and can run on renewable energy only would be a wise policy, and these tools are likely to be of a different scale than the behemoths in current operation. Smaller scale tools may mean more operators, and smaller land-management units.

5. Managing agricultural complexity. Monocroping is a very unnatural way to distribute organisms over a landscape, leading to investments in poisons to prevent disease/pest outbreaks, which end up not working in the long run anyway. With a small labor force compared to the land base, however, it is very difficult NOT to monocrop because humans become overwhelmed by the complexity of managing a diversified production system on a large scale.

6. The long view. Short-term economic incentives may very well play out as presented here, but those who don’t trust the wisdom of this way of thinking and who are considering what are the consequences of these decisions decades from now want to promote a transition that has a chance to work absent reliably available and cheap fossil fuels.

7. Meaningful work. It behooves a society to consider its long-term purpose and to seek ways of connecting labor towards achieving that purpose. As the Amish example points out, doing so leads to social cohesion and stability, which is a good basis for general happiness in the population.

I very much agree with the points made by JB and would add the following (without committing JB):

1. My central tool for looking at the question is going to be the factors going into the profitability of industrial agriculture. I question the relevance of and focus on profitability. Destruction of the planet has been profitable so far. But that doesn't support the argument that it should or can continue. Sustainability of industrial agriculture should be approached in the same way we approach peak oil: estimating the physical resources themselves, not the profitability of continuing their extraction.

Soil depletion, erosion, loss, is a world-wide phenomenon that is worsening. (Lester Brown) Reversing that depletion is crucial. Doing so will be labor-intensive. And it will require intelligent, skillful labor.

Of course industrial large-scale agriculture is more profitable -- it externalizes costs! And the more soil that gets detroyed, the more profitable it will become. That's the whole point.

2. There is also the question of transport. The logic of localization depends on transport. Or rather, the logic of industrialization depends on global markets, both for consumption and supplies. When global transport becomes more and more expensive, there will be a need, more than a need: no choice but to localize. Kunstler's arguments hold up IMO. (Although large cities are superior to subsurbs in many respects, they too will become unsustainable.)

3. There is something between reversibility and irreversibility. I too do not think we can just turn the clock back a hundred or more years. We have to a certain extent burned our bridges -- we have impoverished our natural environment. It will not support our current population without high energy expenditure. We cannot simply return to the agriculture of 100 years ago which was, it is true, much less productive. We will have to both reduce our population AND learn how to do agriculture in a new way. But I haven't heard anyone say that the productivity of modern industrial agriculture can be sustained with declining energy inputs.

There is already a huge mass of people in the world who have moved off (been driven off?) the land into sprawling urban slums surrounding third world cities. The decline of the high energy economy is going to throw hundreds of millions more on this heap. There is but one way: make rural life livable and self-sustaining, reverse this trend. I say rural, but I don't mean just rural: I think here again I agree with JHK -- small dense urban congregations that are surrounded by agricultural areas.

4. Stuart does a great service in stirring up this debate, especially the reversibility issue. How much of modern science and technology will we be able to sustain in the coming decades and century? We cannot go on as we are, and yet we cannot just go back either. We cannot predict the future. But we can at least look at the likely constraints on what the future will be. Stuart isn't guilty of this, but others always drag in future technological progress -- spending an inheritance that may or may not be there. If one takes away that, then maybe it's at least possible to start making some very rough calculations of what the coming generations will have to work with in terms of energy, soil, water, metals. etc. My belief is that the are going to have to move towards a garden earth, i.e. learn how to coax nature/biology into replacing from her (cultivated) skin what we have been forcibly extracting from her bowels. I doubt that it can be as much.

dry matter (e.g., straw) contains mineral wealth mined by the nanotechnology of root systems

Nanotechnology?

Is that what fungus is now, "nanotech"?

There's a bit of irony there, huh? Intended.

Indeed. There are also several questionable premises and statements within the argument - such as this assumed prediction:

"Industrial farming is less profitable at high oil prices than at low oil prices."

Why would anyone predict this, based purely on production/input costs? Profitability has nothing to do with the cost of producing/delivering a product alone, but everything to do with the ability to charge proportionately more for it than it costs to produce and deliver. It doesn't matter if it costs more to produce food if you are able to sell it for a corresponding increase in price. All SS showed was that food prices can increase. So what? Short term profitability for one sector is not the problem - sustainability of the whole system is.

They don't say it. It's easier for Staniford to argue against something he made up than something someone said.

Industrial farmers will only do well financially if they are able to increase the price of their produce in line with the increasing costs of all their inputs. When oil gets to ~$250+ a barrel and fertilizers become very dear, the masses, increasingly unemployed by then, are not going to be able to afford the sky-high food prices. Result: a mass return to home-garden, backyard cultivation, and sidewalk/public park food growinga la Cuba. Before long, falling sales revenues and heaps of unsold, rotting, expensive produce will drive the mega-farmers to the wall.

Or government-run "work farms," a la Kunstler.

Or government-run "work farms," a la Kunstler.

Leanan--

I never said any such thing, nor is it part of my view-of-things.

--Kunstler

'Reversibility" implies not only direction, but distance. Why would reversibility stop at small family farms making butter and cheese and vegetables for the affluent consumer through farmers' markets? Why not reverse to pre-Industrial medieval estates? Wouldn't the large ag corporations be in a position to become the barons of the New Age?

Or what would prevent even further reversal to tribal society -- hunting and gathering by a very much reduced population?

I think we can't really foresee these things, but only model them. Industrial agriculture as we know it in the post-industrial age relies on a huge, and to some extent, hidden infrastructure that is extremely complex and very much at risk.

Tainter is not wrong. He didn't make any specific predictions, that I am aware of, though. He just observed that in the failure of complexity lies the destruction of complex civilization.

Thanks Mamba for mentioning the elephant in my room.

What the heck happens when the average person can't afford the increases?

Scale works exactly in reverse and destroys your business!!!

In order for this analysis to be viable to me it has to answer that question. We have to be thinking net loss of production of stuff and get our heads our of the dollar measurement paradigm. When you are have invested in producing big volumes you will perish if those volumes shrink.

I realize the question isn't easy to answer, but to me it is a given that the large-scale fails it we scale back far enough.

Now, have far back are we going to scale? :)

After reading Stuart's rather long and extensively documented commentary, I can't help wonder if he has any idea what happens on a farm? Have you any idea how large most farms are? I live in the farm belt, and I can tell you definitively that if you drive out into the countryside, you will see VAST farms and nary a person for maybe hours or even days in those fields. Everything that is done in order to produce our immense agricultural wealth spews from the nozzle of a diesel or gasoline tank or from a natural gas well.

Most of the small farmers (20-1000 acres) I know also work full-time somewhere else. Often their spouses work as well. Why? Because their farms don't pay. Not enough to actually live on. The ones who still subscribe to the old, pour-fossil-fuel-on-the-ground and fire up the sterile sponge method of farming uniformly say that without anhydrous ammonia, diesel, pesticides, and fungicides, their yields will drop by sixty to ninety percent. Many in the short-grass prairie will be unable to farm at all.

While all the graphs and the economic abracadabra mumbo-jumbo may seem to make a convincing case, you seem to lack the actual on-the-ground knowledge or the common sense needed to make a factual and accurate assessment. (If you really want the low-down, call Wes Jackson at the Land Institute.)

Someone here mentioned the Amish. In my area, both the Amish and Mennonite outperform the chemical farmers handily. And that means both in strict dollars-in and dollars-out and in energy-in and energy-out terms, after subtracting ordinarily hidden subsidies in the form of pollution, dollars from the government, erosion, sterilization of land, and destruction of ecological diversity. And sometimes even with all those externalized costs.

Anyone championing the idea that agriculture will not have grave difficulties if fuel prices increase, has not been to the Dakotas where people are finding it difficult to get fuel at all.

What you are not seeing is that the farmer who has no fuel, will not plant. PERIOD.

What will happen, I think, is that people in areas where there has been a fairly recent history of truck gardening, and self-sufficiency, and who still have the land to do so, will plant their own gardens. This will supplant the 1500 mile Caesar salad and all that. Which is fine, but we will need protein. It is that lack of the protein grains which will make life unbearable. It will be a lack of grain feed to the cattle that will prove a problem.

No matter what, higher fuel prices will mean higher food prices. That is a fact. When you see people making a choice between driving and eating, then you will see real economic ruin. 'Cause, you know what, they will eat.

If they don't have the money to buy fuel, they will hardly be out there propelling our salad shooter lifestyle with more BS purchased willy-nilly from local Mal Wart in our BS economy. That means fewer jobs, and the cycle spirals down.

The fact is, you have no idea. You are, at best, a babe in the woods. At worst, you are a clueless technophile who is hanging onto the techno-paradigm for all it's worth. Which, my friend, is not a hell of a lot.

Amish and Mennonite farms are successful largely because their use of family labor to the fullest extent. The younger ones are used for weeding the garden and vegetable crops, the older children are used for the more physical chores such as stacking hay and milking. I have always been impressed by the children's work ethic and ability to take on tasks and responsibilities.

But this requires lots of children. At modern society's consumption rates, that would be obviously unsustainable in a very short time frame, at Amish consumption rates, it is not so obvious whether or not it is sustainable at today's population size. As I understand it, around Lancaster, PA the farms have been divided up into progressively smaller and smaller units for succeeding generations, to the point now that land is expensive and the farm sizes are not feasible for supporting a family.

Just as there is labor utilization and machinery utilization aspects to making farming profitable, there's also horse utilization rates too......

In the medium- to long-term, I believe they will, but in the short-term, I doubt it. ;)

Oil won't get to $250 per barrel unless some can afford to pay it. If they can then biomass energy will be similarly higher in value and hence farm products will be similarly high in value. Hence farmers will be able to buy enough to run their operations.

If large scale farms have an EROEI substantially higher than 1 then mechanized large scale agriculture survives. If they have an EROEI lower than 1 then that form of agriculture does not survive.

Stuart,

As always, a well-argued point. Probably also one of the more controversial essays you have written. I understand what you are saying, and have argued a similar point on some other subjects: While Choice A might be the better choice for society, due to (politics, short-sightedness, greed, etc.) we will almost certainly pursue Choice B.

For me, the issue of growing my own food is one of security. In the long-run, I don't want to rely too heavily on others to produce my food. I want to have an ace in the hole, so to speak. Plus, I really enjoy gardening, and it is something I want to pass on to my kids. Do I think it would be valuable if everyone developed some basic gardening skills? Yes, I think it would moderate price pressure on food, which I see continuing to become more expensive as energy costs spiral higher and biofuel mandates are regarded as the best way to mitigate peak oil and high oil prices.

Not controversial at all IMO except here at TOD. Stuart hits the nail on the head. See my post in Drum Beat. Peak Oilers should recognize other fallacies that I have often pointed out. Peak Oil is not fallacious IMO, but some of the arguments now becoming attached to it are. If these erroneous arguments are not corrected or abandoned as erroneous, it now reflects on the Peak Oil idea itself to those who are just becoming familiar with PO. Peak Oil thinkers should be careful to weed out fallacious arguments.

Practical, I admire your tenacity and respect the fact that you are a farmer, but your continued bias towards the viability of corn ethanol is the most fallacious argument of all. Ethanol is a prime example of the Tragedy of the Energy Commons. Say for example the average energy gain for the whole world is 8:1. Then ANY sub 8:1 energy technology is accelerating the use of high energy gain remaining fuels. Ethanol at a paltry 1.3:1 eats up our natural gas, oil and coal stocks MUCH MUCH faster than if we didnt produce it at all. I call it a Tragedy of the Energy Commons, because indeed (and especially due to subsidies) entrepreneurs and farmers (who own the land) can make money at this while the rest of society is worse off (much worse off). Your land ultimately will make you much more money and have a better overall value to society with something other than corn combined with coal or gas into vehicle fuel. You just don't see it yet. Or maybe you don't care.

This argument does not make sense. If I invest one unit of energy in producing corn ethanol and get 1.3 units of energy in return, then to get another 0.3 units of net energy I do not need to extract any fossil fuel whatsoever (at least under the simple minded assumption of economic equivalance of the various forms of energy). We clearly exploit energy sources with a range of differenct energy balances. As long as the energy balance is positive for a particular source net energy is being produced. Of course other aspects of ethanol production (soil loss, water loss, removal of land from food production, etc) probably make it a bad idea.

It does make sense.

Society is run off of a HUGE energy gain. I'm not sure what it is, but lets call it 8:1. Society is 'growing' (but one could argue 'slowly') at this average energy gain - this large payoff subsidizes our roads, hospitals, insurance, social services, etc. and much of it can be considered an 'externalized cost'. If we take some of our remaining high gain energy and get a 7:1 return on it, then everything else stays constant (if non energy inputs are equal). If instead, we take some of it and generate a .3 return on it, it shrinks the growth in the system as a whole. The specific operation will be fine, as you say, they have paid their energy cost and may even profit. But our infrastructure and systems are built on much higher energy gain, and require high energy gain to maintain. This was discussed in Charlie Hall's paper here.

An easier way to think about it is what if we ran out of oil, but had 86 million barrels a day of ethanol. Would that 'matter' to society? You could look at it 2 ways: 1)of the 86 million barrels of ethanol, 66 were needed to get them (86/1.3). 2)to generate 86 million barrels that could be used for 'roads, infrastructure, investment, repair, etc.', you would need 286 million barrels of ethanol, which would then 'free up' the .3, which would be the 86 million. (Yes, ethanol uses nat gas and coal and diesel, not all 'oil', but the general premise is correct)

And, as you have correctly pointed out, the non-energy inputs for bio-energy are 'not the same' as for fossil energy. More land, more water, more pesticides, etc are needed per unit of energy. (This was discussed here)

Claiming that the relatively low energy return of ethanol makes it economically inferior to fossil fuels and therefore incapable of supporting the same level of economic production as these superior fuels is correct. However, claiming that an energy source with a low but postive energy balance "eats up" the supplies of superior fuels is incorrect arithmetic. I am not trying to support corn ethanol as energy source, but making factually incorrect statements does not help to support your position.

If ethanol was on top of all other fuel sources, then your comment would be correct and I would modify my statement. But ethanol is being used primarily to replace other fuels - so the point of my initial statement is correct. (e.g. its not 86 million barrels of oil per day PLUS ethanol, its 86 million bpd which INCLUDES ethanol... The tiger eating its tail....

Suppose we have 200 units (energy units not volume) of high EROEI fossil fuel available to us each year. If we invest 100 units of this fuel (along with soil, water, labor, etc) in the production of corn and produce 130 units (energy again) of ethanol. This out implies that either we have 30 extra units of energy or that we can extract 30 less units of fossil energy. This process is not speeding up the depletion of fossil fuels, although it may be incredibly foolish because of the consuption of non-energy resources such soil and fresh water.

No.

Firstly, we totally agree on the consumption of non-energy resources, soil, fresh water ,etc. so lets put that aside.

The economy grows because of energy gain. Technology and labor help, but without what Roscoe Bartlett calls 'energy surplus' we can't have growth. We are used to a certain energy surplus - in fact, much of the annual surplus in energy just goes towards maintaining our current trajectory.

Liken it to a trust fund junkie. His fathers advisor invested his $1 million into something that made 20% a year for a long time. The trust fund child got to spend 200k a year and built his life (mortgage pmts, car pmts, trips, gambling money, etc.)on that 200k. The market changed/advisor was fired, etc and now the only option is another advisor that makes 5%. 5% is clearly better than nothing, but $50,000 is not enough to pay for the lifestyle that this guy had become accustomed to. So the guy has to either eat into the 1 million principle, or learn to live on 50k a year.

In your example, we can invest that 200 units and get 1600 back (1400 net), or we can invest it in corn ethanol and get back 260 (60 net). Yes the corn ethanol made money for the guy who did it, and it also created energy. But society needs 1200-1300 in energy gain minimum to maintain itself. So the greater % that is allocated to small energy gain technologies, the more society is going to have to use next years 200, and the year afters 200, etc in order to get their 1200 minimum required. This is why allocating resources to small energy gain ideas is accelerating the usage of our stockpiles.

I have already agreed with the statement above as applied to corn ethanol as an energy source; Corn ethanol is economically inferior to fossil fuels. It cannot support the automobile economy or a growing stock market for decades into the future. Please quit repeating assertions that I have already conceded to be true.

The statement that I was critizing was:

An energy producing process with a positive energy balance does not suck energy out of the economy. It may suck other production resources (such as soil, water etc) at an unacceptable rate per unit of net energy produced. But to claim that it sucks energy out of the economy is failure to understand the very concept of energy balance.

Read back up 3 comments - I stated that if we are developing a 1.3:1 energy gain technology on top of the existing pile of annual energy, then you are correct - it pays for itself. But that is not the case, we are using this 1.3:1 energy gain technology, to replace part of our existing pile of energy. Huge difference. In the former, its extra energy. In the latter, it means the sunk costs in the economy won't be met with the paltry energy gain, and we will have to eat up our existing pile faster. You are aware that the new 'record' of oil production last month included over 1 million barrels of ethanol, without which it would not have been a new record.

So, in conclusion, an energy producing process with a positive energy balance does not suck energy out of an economy that starts from scratch, but it DOES suck energy out if the economy has fixed and growing energy needs AND this energy source is replacing something that had a higher gain. (this happens to be case on corn ethanol but will be the case on any quality adjusted fuel technology below the recent energy gain average - here I don't mean EROI - but energy gain/surplus - which is EROI X Scale).

I feel quite strongly that I am correct and this is a vitally important point that most people miss - I know you are long term poster here and I respect your comments and have learned from you - if this still isn't clear email me offlist so we don't further derail Stuarts mechanized agriculture post.

Nate,

Clearly, you are correct. A shrinking energy supply (in toto) is a shrinking energy supply. If that shrinks, then the economy shrinks.

Pretty easy concept.

Sounds reasonable, Nate. We have 200 barrels of oil equivalent. If we invest all of it in getting more oil, we might get, say, 1600 barrels, of which 1400 is the energy gain and goes towards building our economies. If, instead, we divert 100 barrels to ethanol production, we end up with 800 barrels from more oil production and 130 barrels from ethanol production, giving an energy gain of 730 barrels of oil equivalents. It seems clear that we then need to add 670 extra barrels of stocks, or increased production, to get the same amount of energy as we'd expected to. So existing resources get used more quickly (if that is possible, if not, we use existing supply more quickly and our energy availability declines more rapidly).

Tony

This way of thinking is incorrrect. Energy producing processes with postive energy balances do not compete with each other for energy feedstocks. Considers the sum of all of our above the ground energy reserves (pile of coal, pipelines full of natural gas, stockpiles of refined motor fuel, etc). An energy producing process takes some amount energy out of these stockpiles and a later time return every bit of fuel it borrowed plus some extra (I am assuming a positive energy balance). This process does not prevent any other positive energy balance process from operating in parallel using the same stock piles. When energy is being used to produce energy the concept of a fixed energy budget is meaningless.

Hi Roger,

I hate to jump in because I went round and round with RR on this a while back, but also because I think the costs of ethanol are being externalized, particularly water costs, and I don't like seeing food go to fuel. But I agree with you. The slight-of-hand that Nate is using is that he ignores the oil feedstock when refining oil, but you have to include it when making ethanol (system boundaries have to be drawn that way I have been told), so you get this 8:1 number for oil refining and 1.3:1 for ethanol, and all the "awl bidness" folk say QED.

BUT... for grins, lets suppose all the oil you had in the world was 1800 barrels. When that is gone you are out, kaput, no more. Then you can ask what will I do with this. Well you could pump and refine it into diesel using 200 barrels and ending up with 1600 barrels of diesel. 8:1 OK well and good.

Or you could take take that 1800 barrels less pumping cost (let's say negligent for argument sake) and produce 2340 (1.3 x 1800) barrels of oil equivalent in ethanol.

Now for further grins, let's assume that the usage is 540 barrels per year. Having pumped and refined diesel you will be out, kaput, done, in about 3 years, but when making ethanol, each year, when a new crop is planted you will still have 1800 barrels, and now you have a sustainable energy supply. Woohoo!

Now these "ethanol haters" will rightfully claim that we can't replace our current FF useage with ethanol, ignoring the fact that they have been spouting nonsense about efficiency of oil versus ethanol. But with the right ethanol production from say celulosic sources, we could ease the burden on the oil consumption extending our nonrenewable resources, particularly so, if we also agressively conserve oil and recycle some of the water used in ethanol production. Here you will be told that the "devil is in the details", because there is no viable celulosic process. But hold on now, GE just invested in just such a process, with the idea that they could build many plants and replace about 15% of the FF use in the future. The first plant goes on line this year if everything goes perfectly :). Anyway, you'll go blue in the face arguing with some of these folk as they set system boundaries to ensure that oil refineries appear efficient compared to ethanol, wihtout a thought for extending the present supply of FF.

--Ben

That sounds quite convincing, Ben. There is a story by Robert Rapier about this very question: The Energy Balance of Ethanol versus Gasoline. I'm not sure any consensus was reached (it's another long thread, so it would take a long time to read again), however, a few themes emerge, for me.

One is that the BTUs that go into ethanol production are from already processed resources, as far as I'm aware, it is not crude oil. If I'm right, the comparison of inputs to ethanol, versus inputs to gasoline, is like comparing apples with apples. What I'd like to see is a full appraisal of all energy resources that go into ethanol production versus those that go into gasoline production. What would be the likely result of such a comparison? Well, that would be speculation, wouldn't it?

Another theme is the disputed EROEI of corn ethanol. I've heard some proponents, even scientists, claim that not all BTUs are equal. Well that seems a subjective assessment, to me. Either ethanol is net energy positive or not. Pimentel claims that it is not, but he usually gets derided by those who want the reverse to be true.

Lastly, as fossil fuels deplete, ethanol production may have to start using itself to produce itself. In this situation, I'm not sure it would fare too well. If that kind of situation prevailed now (only oil used to make gasoline, only plants used to make ethanol) then the energy balances would be very different.

There are other factors that may reduce ethanol's balance over time and have deleterious side-effects, but these have to do with environmental damage and top soil depletion and would probably warrant a whole new thread in itself.

The slight-of-hand that Nate is using is that he ignores the oil feedstock when refining oil, but you have to include it when making ethanol

You were wrong the last time, and you are wrong now. You are not making an efficiency argument. The argument "what if there was no more oil..." is not an efficiency argument. You are correct, if there was no more oil, then it's a different argument. But then if there was no more oil, the whole charade would come tumbling down anyway.

The oil feedstock is ancient, captured solar energy. You do not include that when doing the energy balance, any more so than you include the corn BTUS - recently captured solar energy - when doing the ethanol EROEI. (What you do include is the portion of the BTUs that were due to the fertilizer). This is what you, and so many others who are confused on this issue do not see.

What is counted in the ethanol EROEI is the energy it took to grow the corn, turn it into ethanol, and purify it. What is counted in the gasoline EROEI is the energy to extract the oil and to refine the oil. The portion of the feedstock BTUs that amount to captured solar energy are not counted in either case. Ethanol proponents wish to count them in the case of oil but not ethanol, which is why they say nonsensical things like "It is more energy efficient to produce ethanol than to produce gasoline."

QED.

I disagreed with you last time and I do so again. You ignore the crude oil feedstock as though it was not an input to crude refinement. In doing so you come up with this specious argument about efficiency. Moreover oil *is* a finite resource and production *is* constrained, so the main issue really should be about "can ethanol production increase our total energy production without hurting us more in other ways.