Does Less Energy Mean More Farmers ?

Posted by nate hagens on December 21, 2007 - 10:41am

This is a guest post on energy and our agricultural system, by Jason Bradford, who has written here previously on "Relocalization: A Strategic Response to Peak Oil and Climate Change". Jason has a Phd in Biology and has written/published on the topics of relocalization and ecological economics. He is the founder of Willits Economic Localization (WELL) and runs a CSA in Willits, CA. (He also has a biweekly radio show "The Reality Report", where next Monday at noon EST he and I will be discussing evolution, addiction and economics. His show can be heard streaming online at www.kzyx.org.)

DOES LESS ENERGY MEAN MORE FARMERS?

Among the cadre of folks who think about food systems and sustainability in the U.S., there’s a concern about the number of farmers and their age. Only about two percent (5,802,000/295,410,000 in 2004) of the U.S. population is part of a farm family, and the average age of principal owners of farms is about 60 years. Since mechanization and the fuels that power machines are what enable such a small agricultural labor force, is it reasonable to assume that a decline in fossil fuels will require more farmers?

Others, such as peak oil educators Richard Heinberg and Sharon Astyk, have suggested this will indeed be the case, even going so far as to put a rough number on the future farmers of America. Their estimates are based on looking at the proportion of farmers in an early to pre-industrial economic system in the United States, when about a third of the population engaged in agriculture. They then adjust for current population size to arrive at the admittedly tentative figure of 50 to 100 million farmers (or members of farming families) needed to feed a population of 300 million.

As these authors point out, not only is the absolute number very large compared to today, but given the age of the current crop of farmers it implies that a rapid education of youth will be required to keep bread on the table. Given the importance of this topic, I feel that more diverse and sophisticated forms of analyses are needed. Just as we use multiple lines of evidence to understand the evolution of life, oil depletion, and climate change, we need to look for confirmation from many angles. Furthermore, better knowledge potentially gets us closer to grasping the scale and rate of change required to cope with the problem in the same way that depletion rates in existing fields and net exports analyses do in the oil situation, or the timing and consequences of melting ice sheets and release of methane from warming permafrost do in the climate system.

Perhaps we can validate or refute this scenario by further use of the comparative method. The comparative method is what Heinberg and Astyx used in their analyses—comparing a future scenario to a potentially analogous historic past. In the analysis presented here, I take as a given that the United States (and other high energy consuming industrial countries) will have less energy available in the future, at least of the type currently used in mechanized agriculture. The comparison I use is not historic, but contemporary. I know that today some nations have much less energy consumption than others and anecdotally I am aware that poorer countries tend to be more agrarian. If nations with less energy consumption have more farmers, it would support the notion that a reduction in energy consumption in the U.S. (and other industrialized countries) will lead to an increase in farmers.

Is there a discernable inverse relationship between energy consumption and agricultural populations among nations?

Let's take a look. First, I had to find total population by nation and agricultural population (which I believe means farmers and their immediate dependents) by nation. These data can be downloaded from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (http://faostat.fao.org/site/550/default.aspx).

Simply dividing the agricultural population by the total population gives the percentage that live an agricultural life. The range of this figure is huge, from essentially zero for places like Singapore to over 90% for places like Bhutan. I really don’t know how accurate censuses data are from the 205 countries used (not all places are fully independent nations, e.g., Puerto Rico is separated from the U.S. in these data sets), but assume figures are in the ballpark. Certainly citizens of Bhutan and Singapore have vastly different livelihoods. According to 2004 FAO data, overall about 41% of the world’s people still live in families who work in agriculture (2.6 billion out of 6.4 billion).

Most nations (about 70%) have 40% or less of their population in agriculture. This means that the fewer countries with high percentages of agricultural workers have large populations, e.g., China and India are 64% and 52% respectively and equal about a third of the total world population. In all likelihood, large populations correlate with high population density. As a 1997 paper by Conforti and Giampietro showed, economic forces in poorer nations with dense populations tend to retain farmers.

Second, I had to find energy consumption data. It is difficult to locate data on use of wood, animal dung, etc., but for commercial energy such as oil, natural gas, coal, and electricity the Energy Information Administration (EIA) of the U.S. Department of Energy has available spreadsheets for download (see table E.1 at http://www.eia.doe.gov/iea/wecbtu.html). While this doesn’t include all forms of energy, it does cover the forms most readily usable in an industrial agricultural system.

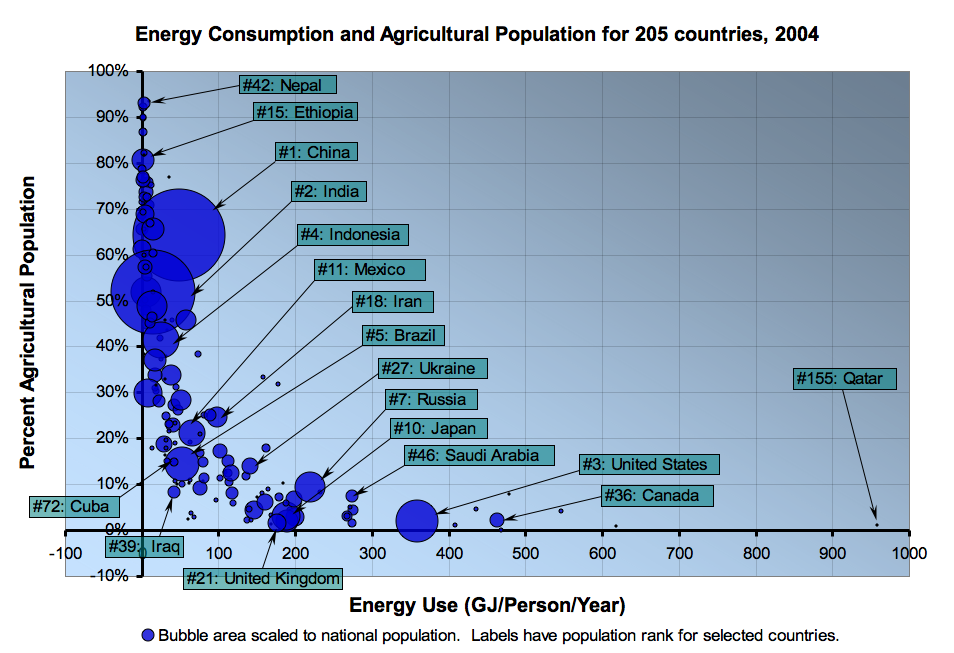

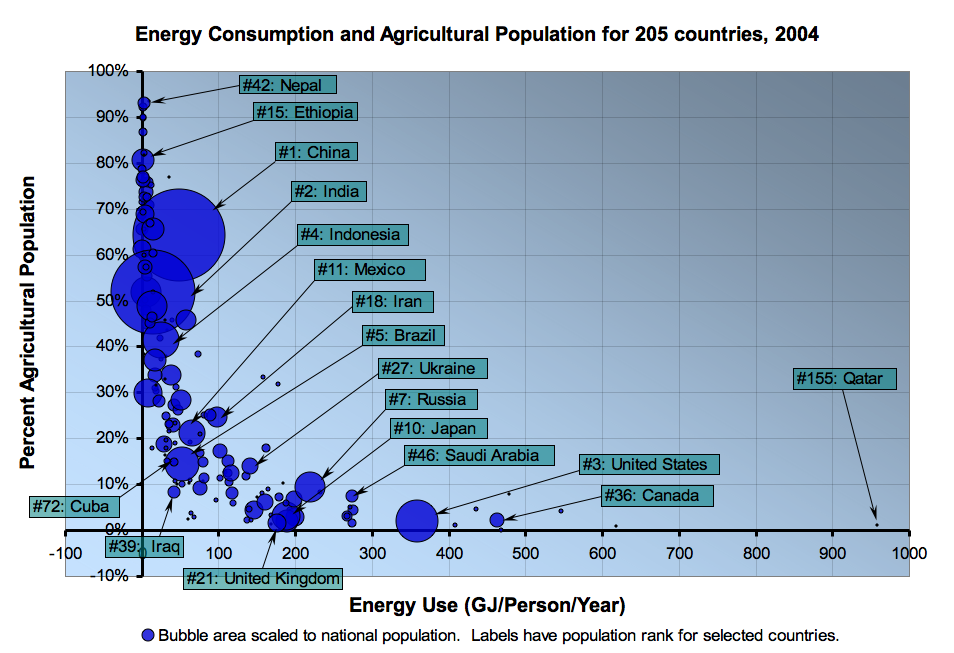

I had to do some work to harmonize the two data sets, which meant using 2004 data and limiting the analysis to 205 nations—which I figure is fairly complete. The figure below shows the results, plotting the percent agricultural population as a potential response to per capita energy consumption. (Note: A big thanks to Stuart Staniford for constructing the bubble plot).

Click to enlarge.

As expected, nations with relatively little commercial energy consumption tend to have lots of farmers. The relationship doesn’t appear linear (perhaps putting energy on a log scale would change that, the X axis ranges from 0-1000 and the Y axis from 0-100), and is not very tight. I see some evidence that tropical nations can get by with less energy than temperate zone nations and still have similar proportions of farmers (e.g., compare Cuba to Ukraine and Mexico to Iran). This result could be explained by heating and cooling demands in temperate countries and/or higher crop productivity due to soils or climate factors.

While these results are supportive of the general hypothesis, I find it difficult to use this method and these data alone to get at the scale and rate of change questions. What might it mean, for example, for the U.S. to be using ¾ less energy by 2050? Many places today are already using that much less energy and have just as small of an agricultural population as the U.S., but surveying the spreadsheet it appears that many could be considered special cases, such as small islands swarming with tourists or tax havens for the wealthy, which can simply afford to purchase most of their food. Other large nations with ¼ of the energy use of the U.S. have between 10-20% of their population in agriculture. Considering that such a range is 5-10 times the current percentage does stagger my mind a bit.

Other questions that arise include: Whether U.S. farming can remain as energy intensive as it is today by taking a larger share of resources from other sectors of the economy? Because no modern economy can survive without them, I would expect extraction and production sectors, such as mining, agriculture and manufacturing to decline at a slower rate than, for example, finance, tourism, and real estate. Are dramatic efficiency gains still to be had in conventional U.S. agriculture, or has the farm sector already been through enough energy and financial dramas to have played out the easy options?

As in any good subject for research, answering one simple question provokes a series of more difficult ones.

Though I may have just done so, I am mistrustful of studying this issue in isolation. Nagging at me is the question of whether the globalized industrial system is inherently unstable in the face of multiple challenges, including energy scarcity but also the converging crises spawned by the surging weight of humanity. Climate change, financial wobbles, violent conflicts and related spin-offs can unpredictably disrupt the vast system of trade that moves fertilizers, seeds and replacement parts that keep industrial agriculture humming. I think we are already seeing hints of this scenario in the U.S., as farmers run short of diesel fuel during harvest season and end up leaving crops in the ground.

Conclusions

While I would appreciate more work towards the questions posed here (and contact me if you have ideas and skills to help), I also caution against analysis paralysis. There are multiple reasons why agriculture needs to undergo a profound shift and spending too much time trying to circumscribe the problem may delay us moving towards appropriate responses. I believe the broad vision of what needs to be done already exists—food that is more local, organic, produced, processed and distributed by renewable energy systems, and using cultivation methods that put the soil health first. Making that argument to those who are reluctant or suspicious, however, could use some better research that connects the dots credibly between energy depletion, climate change, food security, and demographics.

**Acknowledgement: Thanks to Stuart Staniford for both the bubble graphic and checking for accuracy of spreadsheet data manipulations.

References:

i Hollis, P. 10 May 2005. Demographics study reveals facts about farm operators in U.S. . Farm Press. http://southeastfarmpress.com/news/051005-Farm-demographics/; The cited article is based on primary data from the 2002 U.S. Census of Agriculture (http://www.agcensus.usda.gov/Publications/2002/index.asp). The average age of U.S. farmers being about 60, as claimed today, is extrapolated from the 2002 data, with an update due from an ongoing 2007 census.

ii Heinberg, R. 2006. Fifty Million Farmers. Twenty-Sixth Annual E. F. Schumacher Lectures. http://www.smallisbeautiful.org/publications/heinberg_06.html; Astyk, S. 2006. http://casaubonsbook.blogspot.com/2006/12/50-million-100-million-200-baz...

iii Conforti, P and M. Giampietro. 1997. Fossil energy use in agriculture: an international comparison. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 65 (1997) 231-243

iv Reuters. 12 September, 2007. “Not so Corny: Fuel Shortages May Hurt Corn Harvesting.” http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,296551,00.html

Thanks for this analysis Jason. Stuart is dubbing your graphic "The Bradford Curve"...;)

As I plan to show next week with some graphics from systems ecologist Charlie Hall, a lowering of the aggregate of societal net energy, will reduce discretionary investment because more energy must be allocated towards energy production and basic goods (of which food is the most basic). So I believe your hypothesis is on the right track.

Conversation with high school student a couple of years ago. I described my take on the problems ahead. Student said, what should major in? I replied: something related to agriculture would be a great idea. She looked at me like I had grown two heads.

So, what else is new? I guess all we can do is try to persuade those who will listen.

I nominate Jason Bradford and Alan Drake as TOD Persons of the Year for advocating LOF (Localization Of Food) and EOT (Electrification Of Transportation).

Thank you for posting this article. The bubble plot of energy/population/%ag is really innovative. There are a lot of dashed lines connecting energy to food production and indirectly to the percent of people working as farmers. Including fertilizer production from natural gas and the decrease of this activity in the face of higher natural gas prices, in my opinion, can result in the conclusion that less energy means much more starvation. There is also a connection here with the recent Energy Bill and price supports which were, and were not, supported.

High school students do not seem interested in Agriculture.

The Hispanic students see agriculture as lowly peasant labor - something they want to get away from.

Where are these new Farmers going to come from ??

Unemployed law school graduates and unemployed mortgage brokers, investment bankers, etc. would be a start. In any case, when faced with PPP--Produce; Perish or Pilfer (joint acronym effort)--people will have to make a decision.

From "Casablanca"

Which reminds me of some jokes from 1986 (when oil fell to $10):

A geologist applies for a job at a convenience store. The manager said that he had no openings for geologists, but he would like to hire another petroleum engineer.

What's the difference between a mockingbird and a Texas oilman? A mockingbird can still make a deposit on a Mercedes.

deleted

High school students do not seem interested in Agriculture.

Well, why would you?

Long hours of hard physical labor around things that can hurt you - for low pay.

Now take the income from raw farm output and pay taxes, insurance, and for equipment to run a farm. Lets not forget, when you send a grown product off of your farm, you need to replace that atomic matter - so you are adding compost, rock dust or other materials TO the land.

Then look at how many farms KEEP existing due to outside cash flows beyond the sale of farm output.

A sample story but with a happy ending.

Have many farmer friends and neighbours. This guy is very large and strong. Biceps the size of logs. Went to farm equipment show. Bent over pto shaft of new tractor running new bailer to have a closer look.PTO shaft guard was not on correctly and the pto caught his shirt as it turned and started to wind him up at 540 rpm. He had the presence of mind to brace himself with his immense arms and legs. It took off ALL his clothes except his socks.

SolarHouse

That is a great story - only because of the happy ending of having his clothing ripped.

(and it backs up my "Man is farm work dangerous!" point)

It sure is dangerous. I come from a family that includes many farmers over many generations, and the stories are legion. We lost an uncle two years ago when the tractor he was repairing somehow went into gear and pinned him against the wall of the barn...what a way to go. Still...is it worse than dying of stress releated heart disease? I'm not so sure.

The bones of people from many early agricultural societies show extensive evidence of osteoarthritis and bodies broken by hard labour at a relatively young skeletal and dental age. As one who runs a small farm producing most of life's needs and a small surplus (supplemented by a 3 day a week off farm income), I can relate to this. Even with the aid of a 50 hp tractor for the heaviest of work, defeating the life-force embodied in feral photosynthesis (aka weeds) without recourse to herbicides, mulching, preparing vegetable beds, planting and picking the crop, shearing, fixing fences etc, all this leaves me frequently physically spent and sore at the end of the day. But at least the need for weight loss programs and gym memberships don't rate as problems. I do all this out of a doomerish belief in it's inevitable necessity and a desire to build the skill set to pass on to others when required. The vast majority of our convenience obsessed society have no idea what it will take to stay alive in the age of energy descent. Given the choice few would do what I do, how will they respond when there is no choice? Probably try thieving. As a teenager who helped himself to a farmer's apples on my way home from school, I can remember the sting of a 12 gauge loaded with rock salt. I wonder what society's response to that would be today?

My experience farming at home for 20 years and working at an organic farm has been identical.

Then there's the problem of crop loss when you don't spray. I saw whole crops of onions, broccoli, and beans wiped out by galinsoga where I work.

How many people here have actually seen and contemplated the horror of galinsoga?

My new motto: "Prolific internet postings do not a farming movement make."

Todays farm is not the farm of your grandparents.

But it could be. Frankly good honest work should not result in

infirmities nor illnesses. It is healthy to pursue manual labor. Where was it ever proven otherwise?

There are lots of Amish and Mennonites in this part of my state. I see them constantly and they look pretty healthy to me. I have friends my age who grew up on the farms of yesteryear and they are for the most part doing well..even at 70 yrs of age.

It seems that the ones who lived in town are the ones who perish first of many ailments. Mostly heart related.

Yet todays farm is a dangerous place. Due to a vast array of chemicals that can kill or make you very ill. Very powerful equipment that can do the same. Huge amounts of grain dust and pollen due to massive one crop farming. The chicken houses are cesspools as are the confinement hog feeding houses.

We never engaged in such. The chickens were mostly free ranging. We didn't close pen our animals. We treated our livestock well. We needed them.

We lived more in tune with nature and not destroying it.

Again its not the same now as then....BUT it certainly could be if we forgot this nonsense of globalization. Just raised what we needed in this country and pitched all the junk and toys. Raise our children in healthy surroundings. Not penned up like todays animals in confinement structures. Get rid of the child molestors,pedophiles and criminals by executing swift and sure justice instead of 'studying them'.

I would suspect that most farmers have off-farm children that they can call in--if it ever again becomes profitable to farm, the children will come back. I've one uncle with a small farm. He has one scheme or other to keep the family afloat, but I wouldn't be surprised if the farm itself is a losing proposition. He has 3 kids, all married, all gone, all highly educated. They might come back for $100K - $200K / year.

It'd take a crisis for them to return, but they could pull their weight.

Your high school student is neither the first nor the most famous person to react that way. Bertrand Russell once jibed with astonishment (link, small pdf) that the University of Wisconsin would pay heed to worldly concerns, saying: "When any farmer’s turnips go wrong, they send a professor to investigate the failure scientifically."

Incidentally, the University's Stock Pavilion used to be used as a classical concert venue as well as for livestock shows. A story retold by old-timers among the local musicians has it that years ago, one of the Russian orchestras (don't recall which one) objected strenuously when they arrived on tour and saw where they were to play. The response was that since the local symphony sometimes played there, and since the Russians were Marxists big on equality, the locals really could not quite see their objection.

So I guess that while agriculture brings out a lot of mile-wide, inch-deep cheap sentiment - hence "ethanol" as a form of farm support - many folks nonetheless see any closer connection than that as, well, icky. And yes, I also guess you seemed to have an anomalous number of heads that day...

Wow! I am honored. And coming from the ELP-master himself. Should the TOD Overlords set up some kind of poll?

Regarding the sorry social stigma of agriculture. This is really sad. It is not universal among young folks though. There is a subculture interested. They often gravitate toward permaculture workshops, they may go to the degree program at UC Santa Cruz, or join the WOOFERS, intern on CSA veggie farms...but they are generally landless and have many countervailing pressures drawing them away from these pursuits.

Burlington Vermont (Intervale) and organization in Monterey County CA are doing fine work in professional development for young farmers--giving them access to land and capital, and helping them develop markets. Farmlink connects young to old farmers with the idea of future equity transfer.

I think young people today have a harder time swallowing the idea of being sharecroppers, so they get bummed out not owning the land they work. You think "farmer" is stigmatized, imagine telling your proposed future inlaws that you are a "sharecropping farmer."

If baby boomers want food security in their old age they may want to think about transferring equity to those eager to live a life connected to the land.

I'll second the nomination. Jason's PO messages and showing of End of Suburbia at the Willits Enviro Ctr. a few years ago was my wake-up call.

Rat

Another wrinkle would be to make the graphic 3 dimensional - shade/color the bubbles based on whether the country is a food importer or exporter. Red being importer, blue being exporter and shade of color being magnitude. Stuart? Jason?...;)

p.s. Ive just taken the plunge and ordered a Mac, in an attempt to reach the high bar of free internet community graphics that Stuart, Euan and Khebab have set.

Congratulations on leaving the Dark Side.

Did you not get the memo?

They are all UNIX now.

snark

(Windows NT will be a better UNIX than UNIX and, well Macs are nothing more than FreeBSD with better marketing)

As mentioned below, the bubble chart was created in Microsoft Excel - that very same application is available for both Windows and Mac.

How does the myth that "Mac is better for graphics" persist, going on 20 years after it has stopped being true?

I'm not a fan of MS, but Excel is pretty nice. (And has its wrinkles. For example, Vlookup() does not work!!!)

I haven't used a Windows box regularly since XP, but I seem to recall that it handled transparency much less well than the Mac - even in Excel.

I've just recently had the joy of porting a web browser from linux to OSX and to Windows Vista. The Mac is a great box and windows still sucks rocks even loaded Gnu software. The files systems is still painfully slow etc etc. Vista is still pretty much a facelift for XP and you still have a lot of performance problems along with the box just going out to lunch every now and then. And you can forget about firing off a big compile and browsing the web. I was actually pretty disappointed since I'd heard it was a lot better.

It looks like the U.S. is on a fairly "flat" portion of the curve. That means fairly large changes in energy use will not cause large changes in %ag for the U.S. (assuming we stick to the curve as our energy use declines). At least until we hit about 100 GJ/person/year (eyeballing) and the slope changes. It could take the U.S. a long time to get there.

On the flip side, all those poor countries on the y-axis could see large decreases in %ag with only modest increases in energy use and, of course, large increases with only modest decreases in energy use. So, as access to energy decreases, wealthy countries on the flat part of the curve change little and poor countries near the %agr axis scramble.

Also, it looks like your curve would fit nicely to an inverse power law. Have you done a fit for this? i.e. : y = x^(-z) where z is some positive #

That's my interpretation also. If progress down the curve were to be viewed as reversible (which is probably a rotten assumption, but for the sake of discussion), then the US could dramatically cut energy usage before it had to increase agricultural population.

This is common sense - it's obvious that the US wastes a high fraction of the energy it uses in ways that have relatively small marginal utility (like driving 15mpg vehicles versus 60mpg vehicles), so there's a lot of scope to cut energy use in those ways before more radical things are needed (by which time we hopefully will have ramped up renewable/nuclear energy and have figured out better batteries, and most of us never have to revert to peasantry.

This is a point I hope comes across in the article too--how much more can be reallocated to the productive sectors and how much more efficiency can be gained in general and in agriculture/the food system. I could say much more about this but want to wait for another post.

However, I take a more precautionary stance. Since food is so critical and there are a multitude of reasons why the current food system is unsustainable, it doesn't make sense to me to wait around for government, academia and industry to sort this out. As far as I can tell, they don't understand energy, climate and soil issues well enough to have prevented the mess we are in.

The whole strategy of packing people into denser enclaves and importing food from afar is also possible but I don't believe sustainable in the long run.

This conversation eventually gets down to the level of the first law of thermodynamics--soils are mined by root hairs and associated fungal hyphae and these minerals are incorporated into every cell of the plant. When plants are harvested and their bodies removed the soil is depleted. Replacing the lost nutrients, which can be almost impossible to measure properly, requires a cycling of waste from the consumer species back to the decomposer species. How does this happen when the consumer species lives 2000 miles away from the decomposer ecosystem?

Excellent article, Jason.

Two brief points on this subthread;

1. If one extrapolates the energy use of a developed country far to the right on the graph and assumes that little change will take place with reduced energy, this will ignore many non-linear variables, such as the impact of other declining crucial inputs (i.e., phosphorus, nitrogen, etc), the cost of transition to different forms of agriculture production, the lag time in infrastructure and supply market changes, and so forth. Note that the UK uses less than half the energy input as the US for the same percentage ag population, though imports and exports have not been taken into consideration.

2. "packing people into denser enclaves" is one approach to reducing energy consumption in buildings and transportation, so there are tradeoffs. One ideal arrangement that does not require high produce transportation costs (as ag is close by) is the carfree cities approach, though I acknowledge this would be difficult to start from scratch in a petroleum starved economy.

Yeah, that's the question. However, if it is then it provides info about the vulnerability of a given country to an energy shock. The magnitude of the slope of Jason's curve could be taken as an Energy Shock Vulnerability Index (ESVI). The higher your country's number, the more likely your country sees societal disruption due to a loss in energy access. Or maybe POVI would be more catchy.

I agree with Stuart. We have so much room to cut back on energy usage without much impact on our living standards that I do not see why we will have to give up using farm tractors for example.

I would rather shift to moving around in a 80+ mpg subcompact hybrid diesel than start following an oxen around with a plow.

We also have non-fossil fuels energy sources that can get scaled up. We could run a lot more agriculture off of electricity and we will do so once oil production starts declining. Nukes, wind, and solar will power our tractors.

This is a great start. The bubble curve looks roughly like 1/x to me, i.e. ((GJ/person-year) * (agricultural fraction of population)) is roughly constant.

There are two forms of energy importation that might be useful to add: fertilizer, and food. Actually, it would probably be good to account for export as well. If a country burns lots of fuel to make fertilizer and then exports the fertilizer or the food, that shouldn't count as consumption.

Anyway, you've made an excellent start. Thanks.

Hmm. The curve could also be 1/x^2, for example, or 1/sqrt(x). The author might want to linearize his data and check that. It is rather hard to tell from eyeballing the graph. I guess it depends on whether knowing the exact functional relationship is useful for anything or not.

I suppose having a function would enable those modeling energy to estimate impacts in the agricultural population.

If somebody wants to work with the data and produce a function I'd be happy to share the spreadsheet.

I'd be happy to do the linearization. I'm pretty much bored, kicking around at work, avoiding writing up the research I should be writing up. But I've never contacted anybody here off-list...How does it work here?

I tried quickly inverting the agricultural percentage last night and plotted that scattergraph. In the reciprocal dimension, it looks much more scattered, and a straight line only has an r^2 of 19%. I mean to plot the inverse of that straight line on this graph, but that requires a bit more tricky Excel bashing (to plot a line on a bubble graph, which I might do tonight).

Beyond getting the "best fit" to the graph, I would suggest modeling this relationship as a power law. Take the limiting cases: On the y axis you want a y intercept at 100%. This is because (in the ideal case) you have a totally agrarian economy with everyone making enough food by subsistence farming to...subsist...if you know what I mean. However, there is no logical x intercept if you assume that there is infinite energy available (TOD heresy) :P Well, Qatar provides a good example of what I mean.

A function of the form y = 100e^(-Ax) seems like the best place to start as a mathematical model of what's going on, that matches the naive physical situation. It also suggests an easy differential equation, which in turn could be used to model this dynamically :)

It would be convenient if the author could make his spreadsheet (or some other form of the data) available. I suspect that taking natural log of both variables will probably result in a roughly linear fit. Here's a graph I put together a couple years ago:

Energy per-capita versus income per-capita appears to be linear with an R2 of 0.8 — a darned good fit for these types of question. Economies that require 40-50% of the workforce for agriculture are low-energy (hence low-income) economies.

Unless/until agriculture becomes high(er) income.

But it never has. Agricultural workers may get a bigger piece of the total pie as more workers need to be diverted to ag efforts, but the total size of the pie will be shrinking at an even faster rate. Because one farm family can feed itself and 49 other families today, those 49 other families do things like build the hospital, build the equipment used in the hospital, staff the hospital, etc. At the point where 25 families must work in ag to feed the 50 families, it follows that there will be fewer hospitals, less equipment for hospitals, less staff for hospitals, and on and on. Ag output remains the same -- enough to feed 50 families -- but all the other outputs of the economy shrink dramatically.

Under any sane distribution of income you want to use, the families in the second situation, including the 25 ag families, will be worse off (poorer) than the single ag family is today.

What about Cuba? I don't have data but am told that farmers make more than doctors, lawyers, etc... Is this true?

The thing is, it's not "be a farmer or work in a hospital." There are a whole swag of other jobs - most non-farmers don't work in hospitals. As in all societies, productive workers support a large class of people who produce nothing tangible and are mostly idle. In medieval societies the idle class are called "nobles", nowadays they're called "accountants" and "lawyers" and so on.

The high-energy society supports a large class of idle people on the back of productive work. If the amount of energy available declines, much of that productive work will decline, so that the idle will decline, too. For example, if the oil runs short then a lot of commodities speculators will lose their work, and thus a lot of bankers, and secretaries to bankers, and IT people who write the software they use to keep track of prices and sales and purchases.

In a society where oil is too expensive to use in any form on farms, yes you're going to have a lot more farmers. But that needn't mean less doctors and hospital cleaners - it might just mean less accountants, stockbrokers and so on.

Every accountant I personally know works very hard, especially so around tax season and around the quarter end if they are in a public company.

Same thing with the lawyers I know.

And without both of them this incredibly complex world would have no one to help us regular folks understand and thrive in it. I ask both my accountant and my lawyer for advice and much more often than not it is very, very good.

My accountant friends and lawyers friends would laugh to hear you compare them to nobles! My guess their response would be, "If only..."

Of course they work hard. So did medieval European nobility. They had constant activity, it's just that it produced nothing tangible. They earned their keep while producing nothing tangible, whereas other groups in society had to produce something tangible to live.

If my local baker drops dead then the shop closes, and I have to find a new place to get bread. If my local councillor or accountant drops dead, nothing tangible is subtracted from my life, unless I knew them personally.

Certainly they assist us with the complexity of the world; but they also contribute to it. Our medieval nobles, likewise, protected we their people... from other nobles, who in turn protected their people from our nobles. They thus created "work" for themselves.

It's fair to make a distinction between those who create some physical product, or maintain existing products or people, and those who don't.

That's Adam Smith, an accountant will probably have heard of him.

I imagine that in such a situation a variety of jobs would cease to exist. Socially necessary work like doctors, nursing, teachers, energy workers, sanitation etc would continue. I can see many of the consumption & service based jobs dissappearing. We would still have our hospitals & schools staffed, we may not have the shop assistants or middle level management at the local pizza hut or sunglasses retial store.

If you could plot energy consumption specifically used/related for agriculture, it might be much more meaningful. This also might be useful in showing how efficient energy is used for agriculture.

The 1997 paper cited in this article calculated energy consumption in the ag sector, and food output per unit energy, per unit labor, per unit land. In general, those nations with more labor input and less industrial inputs had a much higher food net energy.

This vision is based on assumptions that we don't know are valid.

I had planned on writing a long article on the fate of local, "organic" farming for this website, but the task has proved so daunting--and I have such little spare time or stamina to pursue the project--that I'm just going to post some general thoughts here. My initial readings have given me a dismal outlook.

It's always assumed that less energy is the fate of the US and that more farmers/decentralized farming is the answer. But how do we know that? I think we merely hope for it to be true. We're cornucopians, in the something like the original meaning of the word.

What if the US military ensures a continuing source of liquid fuels to the agricultural centers of the country? What if, as Professor Craig Bond Hatfield mentioned to me a couple of years ago, recreational gasoline use is "requisitioned for agricultural use"? (This wasn't a part of my interview with him.) In this way, the conventional agriculture paradigm could chug along for who know how long? Decades.

And what if there is indeed an energy "shock" to the system? An unsettling analogy comes from physiology, which I learned in my EMT training: In "hypoperfusion," the body senses that blood (or, in the US's case, oil) is not adequately getting to the tissues to oxygenate them, so the body "compensates" by increasing respiration and heart rate, and by shunting blood flow away from less critical systems, like the extremities. (People in early stages of shock present cold and clammy skin.) If the hypoperfusion persists or worsens, the vital systems of the body--organs--begin to shut down.

In our current agricultural system, "organic," localized farms are decidedly not fulfilling the role of vital organs: they're mere extremities. Large, centralized farms are the vital parts.

Who's to say, if oil supply is curtailed, the US won't "compensate" with a further consolidation of the existing vital systems? Who's to say the "extremities" won't be shut out during the "compensation" stage, leaving the "organics" movement and other non-vital agricultural systems to wither and die?

Things could transpire in ways we haven't even begun to imagine. And if the peak be imminent, and the decline as drastic as some make it out to be, then we're in for a world of trouble.

*****

Add to all this a wrinkle, a dilemma, that people on this site have not even begun to address:

The "organics" movement in its current manifestation is a scandal, sometimes even an outright sham.

1.) The "organics" movement sits cheek-by-jowl with the rankest of superstitions. For every Pimentel carefully plotting energy flows through organic systems, there are ten Steiners telling us to stuff manure into cow's horns as a way of "energizing" the soil.

Therefore, if there is an oil shock, and the hue-and-cry for more "organic" farmers hits the mainstream, the debunkers are going to already be there in force, waiting to decimate the outrageous claims of the current crop of "organics" aficionados.

The high priest and priestess of the current cry for "organics," Heinberg and Astyk, are not immune from this infectious hocus-pocus:

This implies that "organics" foods are somehow better, "more nutritious," and that conventionally grown foods are less so, which is just neo-kosher claptrap.

This is the most specious nonsense. It sinks to the level of what Morris Berman calls "manichaean" thinking: it's not enough that one's particular tribe has the "answer": all the others must be devils. It is the very apotheosis of "biting the hand that feeds you."

2.) In my meager experience here in Maine, the "organics" movement is in nowhere near the condition to step in and fill a void should local shortages develop. My own boss at Rippling Waters Farm is peak oil aware, but he owns a mere 4 acres.

The larger umbrella organization in Maine, MOFGA barely hints that they know what's going all. They seem indifferent to peak oil.

But they know what's going on. In 2004, I wrote an article for MOFGA's newsletter describing peak oil and asking what MOFGA would do if there should be a sudden call for organic farmers in Maine. Wasn't this a vast opportunity? The Director rejected my article thus:

This implies that "organics" foods are somehow better, "more nutritious," and that conventionally grown foods are less so, which is just neo-kosher claptrap.

Tell ya what. Explain why the brix level is higher in organically grown food model VS the Ammonia and pesticide growth model.

Source?

And so what?

Hardly paradigm-shifting.

Source?

So you want me to provide you with an education? I'm all ways up for changing a mind.

And so what?

Oh. So really, you don't care if your claim of neo-kosher claptrap is wrong, your mind is not open to correction.

For the rest who are here for learning a bit about the rest of the world, the idea is this: If you measure the sugar content of the plants you have a cheap, reproducable and objective metric of plant health - the higher the sugar (for that plant) the more healthy the plant. (Because plants use sugars to build their own tissue)

http://www.highbrixgardens.com/highbrix/highbrix.html

Hardly paradigm-shifting.

I agree. Around here, calling bullshit on some post and seeing a response of "so what" is not a paradigm shift.

b3NDZ3La, while I'll admit there is plenty of magical thinking around the organic movement, I'll suggest that the "heirloom seeds" movement is paradigm-shifting. Why?

Even when I was attending a "Land Grant" college back in the '70's it was projected that hybrid plants would lead to obesity in the countries that used them widely. This is because while producing protein is "expensive" for a plant, producing carbohydrates is "cheap" for the plant. So hybrids tended to produce merely bloated fruit or seeds, inflated by huge amounts of carbohydrates without corresponding increases in protein, vitamins, and antioxidants. For example, in potatoes and eggplant most of the vitamins and antioxidants are in the skin or just under them; potatoes and egglants used to be much smaller, with a much higher surface-to-mass ratio. Now they are huge balloons of carbs, with a thin skin stretched over them.

Point is: green revolution plants produce impressive tonnages if you stuff them full of fertilizers and irrigation, but much of that increase in tonnage is carbs to make fat animals and fat people.

Man, in his hubris, figured he new better than God ( or evolution, take your pick : )what plants should produce for people to eat, and could get something for nothing. We are soooooo screwed!

PLAN, PLANt, PLANet

Errol in Miami

This is because while producing protein is "expensive" for a plant, producing carbohydrates is "cheap" for the plant. So hybrids tended to produce merely bloated fruit or seeds, inflated by huge amounts of carbohydrates without corresponding increases in protein, vitamins, and antioxidants.

Thanks for that tid-bit. Had not heard this one before.

It's easy to become bitter when one is knowingly and willingly encouraging the parasites around them with the ridiculously cheap fruits of their labour.

"Organic" is a joke, Wallmart moves more "organic" product than Whole food and to para phrase Michael Pollan ' we are one Legislative move away from an organic happy meal'

I'd suggest a year off, mess around with cover crops. Make some money.

Our food system is a wonderful thing to ponder. GMOs, the loss of crop diversity, pissing away top soil, nitrogen run off, subsidies, slavery, replacement parts, on and on and on. I don't think we're going to make it.

By the way I only ask $16.95 for my seed garlic. Not "certified organic"!

b3NDZ3La - This year we, (or I should say OSU) hosted the FFA (future farmers of America) event.

2700 fresh faced young'uns who are intent on being the food producers of the future.

Some I talked to said much of what you just wrote.

I have quite a bit of PO propaganda around my shop and chatted up several of them to see if their was an awareness.

For the most part it was blank looks but one small group lead by a 6'4" outgoing young man said yeah they understand it but don't buy the whole Die-off/ nuclear booming thing.

I asked how they saw it effecting farming and they said in essence that they thought it would just put more emphasis on highly productive processes and expect tons of money to start flowing their way.

P.S. These kids were for the most part very sharp, personable, dynamic even, and I never saw a fat one in the bunch.

Last year the big meeting of the Vermont chapter of the Northeast Organic Farmers Association (NOFA-VT) put Peak Oil front and center, including a keynote speech by Kunstler.

Congratulations! This is one of the best posts I have read in a very long time. You are so right. My husband and I have just purchased 13 acres of "black dirt" 60 miles from New York City. We have been considering whether or not to get "certified" organic and have decided against it for a number of reasons. Mainly, we do not want some person from the certification board spending six hours at our home pouring over records. We rather spend the time planting some seeds or sitting by our fields watching the sunset and sipping a nice glass of port. Life doesn't get much better than that. So, when our "dear" customers ask about our methods, we will have two responses: we are black dirt farmers or we practice "veganics." How's that for blowing more smoke?

Thanks. Sounds like you're having fun. If that ain't what farming is all about, then I don't know what is.

I can't tell you how gratifying it is to walk into the cellar and see months' worth of food that we have grown here ourselves, without massive and expensive inputs of bought items, like fertilizers and pesticides.

But this doesn't make our food more virtuous than the stuff at the store. It just makes it literally the fruit of our labors. It also makes us secure and free.

The people stumping for an organic conversion of the national agricultural system are in for a pounding that they can't even imagine.

"Organics" is a marketing ploy. It is a scam. I want a new name for honest, local, low-energy farmers...

Lo/Cal farming?

Nah. Too "soft drink."

It is a bummer how good terms get co-opted. I could rant about the word "sustainable" for example.

The farm I help operate is certified by a local group called Mendocino Organics. They charge almost nothing and are made up of other farmers.

I appreciated the few things they asked me to do to become certified, specifically writing up a soil fertility plan.

http://www.mendocinorenegade.com/

Yes, "sustainable," and "green," and "wholesome," and "natural," and "eco-" anything, and "nutritious," and "alternative," and "community," and "bio-" this and "bio-" that...

Hmm, yeah that sounds about right. Any day now we'll be saved by this rising tide of ethanol and other biofuel. It's gonna give those terms a really bad name when hunger is more widespread.

Lo/Cal farming?

How about "sustainable agriculture"? Or is that term already too worn out?

Thanks for the nice rumination, b3NDZ3La. That explains a lot of what you were talking about last week.

And that MOFGA "Whole Life Tent" is a hoot! I always thought that was what marijuana was for :)

But, yeah, your medical shock analogy sounds about right. There will be this period of time when much more energy will be expended, wasted really, by TPTB and everyone who remembers the good old days of 2007 in a vain attempt to "get back to normal". By the time that effort is abandoned, or simply moribund, we will be a whole lot farther down the nonfarmer/farmer ratio on that keypost graph.

I think it's going to be important to find the right sort of place, maybe a little farther off the beaten track. But it's hard to estimate just how far off it needs to be for that sweet spot between small town life and wilderness. How about somewhere around Dover-Foxcroft?

There will be this period of time when much more energy will be expended, wasted really, by TPTB and everyone who remembers the good old days of 2007 in a vain attempt to "get back to normal".

Whoo, boy. Do you ever call it here.

Our pretenses at predicting the future--let alone preparing for it--are sure to be . . . imprecise.

Good luck getting that off the beaten track place!

It will be difficult to distinguish between "recreational" and other use of gasoline. But the concept is clear: when the crunch time comes (after "market forces" have killed off a lot of discretionary demand) all governments will be forced to allocate fuels according to their most important use, and agriculture will be high on the priority list. The rest between what is really needed to keep essential economic functions continuing and available fuel supplies will be rationed to private motorists in a constantly diminishing quota (per month per car). There will be no other choice.

In the Australian context I have calculated that assuming

(1) a 30% drop of oil supplies in line with the estimates of the Energy Watch Group 2007

(2) a continuation of all commercial, truck and regional/rural/agricultural traffic at current levels

(3) petrol/diesel adjustments can be made at refineries

motorists in Capital cities would have available to them by 2020 only 20% of their current fuel usage.

I really like the graph. Can anyone tell me what program was used to make it?

Jason, I attended a presentation 10 years ago about future workforce trends. The speaker pointed out that in 1905, 50% of the North American population were direct farm laborers - like modern Indians according to your graph. By 1948, less than 10% remained on the land, while manufacturing peaked at 40% of the workforce. From this perspective, the great depression was caused by the development of good, cheap farm tractors after WW1 displacing people as farm labor. Manufacturing has been steadily declining Since '48, due mostly to automation improvement, though offshoring gets the credit. The "service" economy is now the biggest employer in North America.

I predict the rise of the energy economy. Renewables, nuclear (a typical nuc. employs a thousand people!) and CO2 sequestration of coal will require 20-30% of us, and small, regional "artesan" manufacturing using CNC tools will provide a resurgence in that sector.

Primary industry will be located near the minerals.

Farming will continue to require almost nobody, as electric tractors will operate just as well as the diesel ones.

Workers will have to come from the ranks of financial services, retail, etc.. and may well be happier building solar panels than CDOs.

It was done in Microsoft Excel. I gave the editors a very plain graph. Somehow Stuart made it look very pretty and I think I learned how.

Are you aware of any major company developing electric tractors?

It takes a long time to retool an industry. I fear we are going to muddle through with much of the infrastructure we currently have and only slowly adopt new equipment. I believe tractors turn over much more slowly than cars, and farmers are very hesitant to buy something without a great track record.

When you need to get the crop on 1000 acres out of the ground within 7 days, and plan on running your combine for 12 hours a day...it better not break down. Same issues on the planting end of the schedule.

The whole notion of complexity in tool sets would be very interesting to explore. Old-fashioned reapers with few moving parts could be used by a couple of people and take care of 10-20 acres a day. Now we have giant machines that can do an order of magnitude above that, but they are not very tolerant of missing pieces.

Tractors and combines use less power than you might guess by looking at them. They need torque, not speed, and are geared down accordingly. I grew up riding an International Harvester 20HP diesel tractor, and even combines can use 150 HP.

You should also consider duty cycle. A tractor spends the great majority of the time in the shed, then goes 24/7 during planting and harvest. This makes reliability very important, but average power consumption is low. One windmill running an electroplater all year could make enough zinc to run a metal-air battery through harvest, with no longer spent for re-fueling than a diesel tank takes. Combine systems are hydraulic, and can as easily run from an electric power pack.

Western civilization need not collapse with the end of fossil fuels, but probably will given the lack of sensible solutions being offered thus far.

A small outfit near me makes pint-sized electric tractors:

http://www.electrictractor.com/

And, as Jason Bradford is aware, Steve Heckeroth in Northern California has been modifying and building solar-electric tractors for quite a few years now. If any investors out there are interested in pursuing the idea, Steve welcomes their participation.

Why the big manufacturers like John Deere haven't gotten into the game is an interesting question...and perhaps not dissimilar to the question of why the Big Three haven't made a more serious pursuit of electric vehicles.

The issue of tractor and implement size has been one of the primary drivers to larger farms. The new models have always been larger, and operate most efficiently with larger pieces of ground.

As you get to having to purchase new machinery, the cost and the size have said "quit" for many. One it's a huge loan, two, you need more ground to work it right. So your place is up on the block, and others that can afford the larger machinery expand. I've seen it played out too much. Thousand acres isn't enough to make it go.

Another issue you brought up is labor-it's hard to get the kids interested. Neither of my boys have any desire. Alot of work. No glamour or status. Little freedom. One's off as a teacher, plenty of free time, the other is studying for engineering. Maybe later they'll want to come back, but I kind of doubt it.

To me, the question of agricultural employment centers upon how one sees the future. On the one hand there are those who foresee re-urbanization coupled with TOD - what I call Business As Usual Lite. On the other hand, there are those like myself who foresee a dispersed population.

In BAUL, it would be expected that a far smaller percentage of people would be involved with agriculture. However, I do not see this as a sustainable paradigm. I've discussed this on other posts so I won't repeat my arguments as to why I belive this to be the case.

Rather I anticipate extended family and afinity groups living together to personally produce the majority of their food needs with the possible exception of grains such as wheat and rice. In this instance, essentailly everyone would be involved with agriculture, perhaps not full time, but at least a significant portion of their work day.

Todd

Re. Education - I am forever sorry that I majored in chemistry rather than ag. Interestingly, I have now spent more of my life growing stuff than my time in the chemical industry. Being a plant manager was boring and not intellectually challenging compared with producing food.

Todd, had you majored in ag instead of chemistry, you'd have spent more time in a chemistry lab than growing stuff. If I had majored in ecology or evolutionary biology instead of finance, I'd be trying to be an investment banker at this stage of my life. We gravitate towards what we're missing and (hopefully)toward what matters.

Nate - I don't know. I went to a spiffy private school in the 50's. For the price of the education I could have gone to a state school and had enough money left over to buy a small farm.

I think a lot of our higher education choices reflect how we grew up. I loved growing stuff as a small kid but my mom was an elementary school principal and my dad a purchasing agent and the old family farms were long, long gone. There was one surviving farmer near us who still plowed down with his horses but he just did it because he liked doing it.

Life is strange.

Todd

And how much of that farmland and equipment was originally obtained w/o capital from family or your old Chemistry existence?

(How will someone who's just turned 18 get a loan to buy ag land and associated ag processing tools as a more broad question)

There are lots of ways to get started in farming without having a huge pile of cash to invest:

1. Find a land owner who is willing to let you farm his or her land. There are lots of older people who own land and would like to see it put to good use but don't have the ability to farm it themselves. I myself have only three acres but am immediately adjacent to 50 acres of ag land owned by a nice older lady. She lets me grow vegetables and pasture a milk cow and bull on her land for nothing.

2. Go to www.growbiointensive.org and learn the biointensive method of sustainable farming. You only need some simple hand tools and your own hard labor and desire.

There's something called "SPIN-farming" that promotes the idea of using small spaces in people's backyards to be a full-time farmer:

http://www.spinfarming.com/

You could also by Coleman's "Four Season Gardening" for $15 off Amazon.

I welcome this topic and believe it to be of extreme importance to this country's future.

As many know I post quite often on my observations regarding the topic of farming as I see it and work within it here in

an important part of the agriculture areas of Kentucky.

However most of what I post seems to only attract the attentions of the very few others here who are into agriculture. Most I think is dismissed as either doomerism or redneck jabberwocky.

However I still post those observations on the local effects of climate change , seasonal farming periods and other aspects of this. Workers,cost of fuel,grain trucking and so on.

Right now I am entering this as I sit in a farmers workshop connected via a DSL modem and all the PC gear I have installed and maintain for his operation. So I am 'hooked' in though I no longer actively farm my land.

I believe that to find true values for the number of farmers some definitions are going to have to be made as regards the very generic term of 'farmer'.

So let me add a few for others consideration.

First you have landowners. And among them you have ones whose land contains very little tillable ground yet they will enlist themselves as 'farmers' with the governments USDA and it partners programs(extension office ,FSA,etc). They do this for tax purposes.

Then your have landowners who have varying amounts of tillable land. Some may be locked up in soil bank programs and not being farmed but are titled as 'farms'.

Then some landowners may be farming their land and some may be cash renting it out(more common) to what is termed by the IRS Schedule F as 'operators'.

Within the number of 'operators' you have those who farm land they rent, farm their own land and some of others and various mixes which can change somewhat as they expand their operations.

Also you have those termed farmers who do not cultivate and produce grain or other crops. These can be dairymen. They can be cattlemen and some may raise sheep or goats and some do confinement feeding. Again they might or might not be considered by those who do the counting as 'farmers'.

So its daunting to mine the relevant data as exactly how many do which of all that is placed under the generic term of 'farmer'.

Also those who do confinement feeding may produce feed crops for their own feeding, sell the output of the confinement process for spreading on their or others fields as fertilizer.

Farming then is a very varied area to understand.

In my friends case he owns a few farms and rents some land both on shares and cash rent. He farms a tad over 3,000 acres and also has a side business of hauling and trucking for other local farmers as well as himself.

Ok..enough of that.

Here is one point I have made in the past. When I lived as a youngster with my grandparents they farmed 100 acres of which only about 50 were 'cleared'. On that farm and others in the past they raised 14 children, one of which was my father. They did it without the 'slave labour' aspects some speak of. It was a very healthy life and I flourished in it. We were going thru the back end of the depression and then thru WWII, yet we had plenty to eat and did very well.

The farm was sharecropped as my grandparents did not and never did own their own farm.

Now today. My friend is divorced and has one son. He has difficulty even providing for his and his son's livelhood and thats running a 3,000 acre operation. He does manage to keep some employees but pays minimum wage doing so.

He does not live but other than a normal lifestyle. Not opulent or ostentatious. The comparison is astounding to me!!!

Currently we are at a slow period due to the season. Its time to repair equipment. I have a bin blower to fix and a chain saw to repair and some radios to replace. Check out some wireless gear and update one of the big tractors radar gun or replace it with a GPS unit to measure acreage input/output from the tractor computer.

My opinion is on TOD we need to more closely hue to what is happening in agriculture and thereby be able to make wise plans for the future and to raise the 'hue and cry' as we can.

As another in a Key Topic said..this is really the Age of Agriculture and not the Info or the Industrial Age.

We need to concentrate very much on the future and present of agriculture. Our very lives depend upon it.

airdale-wondering how many on TOD are real farmers or work in that area

I attempted to grow 40% of my own food this year, though in the end it will be about 15% - but I did give alot away and my freezer is still jam packed. So if I HAD to (as opposed to getting sushi, thai food at restaurants, etc.) I suppose it would be close to 40%. I shot 2 deer (sigh...), had 38 tomato plants (20 too many) 9 varieties of squash, kale, carrots, parsnips, hundreds of pounds of potatoes (but had bad larvae beetles that ate a good deal of them), lots of garlic, beans, cucumbers coming out of my keester (not really), lettuce, spinach and 3 acres of clover/feed for deer. It was a start - MOST importantly, it was a) a foot in both worlds and b) I really enjoyed it - though the harvest was a lot of work.

BTW, I haven't seen it posted but Nate got a mention by Pimentel in the December 17, 2007 issue of Chemical and Engineering News, the weekly news magazine of the American Chemical Society. The article is entitled "The Cost of Biofuels" and is a debate between Bruce E. Dale of the U of Michigan and Pimentel. I'd proved a link but the article is behind a paywall and I only get the printed magazine. Yup, I'm a member of ACS.

The Costs Of Biofuels.

I can't find a 'lets make growing food illegal' claim outright - so I have to use this link instead.

http://www.rawcuisine.co.uk/whats-happening-to-food/codex-alimentarius/

(I hope the codex alimentarius objections are just tin foil hattery VS a real problem)

I am actively looking into acquiring 20-60 acres of farmland/woodland here in western WI with the hope of beginning a modest farming operation while I continue to be employed as a EE. I have read some books and obtained the local county soil survey from the USDA, but I am having trouble understanding the different soil types and their implications.

Could some one here recommend a few books on soil geology, land purchasing and soil improvement, applicable to the loamy sands found in this region. Also, how important is shallow bedrock (sandstone) to farming? Any advice would be greatly appreciated and I will try and put it to good use.

Regards,

Andy B

I live in central wisconsin and the soil is poor. Its called 'oesterele' soil and is left over silt and sand with a water table 3 feet under the surface. i worked hard to get a small plot of 'renewable' soil that won't require amendments all the time. Heres a link to soil maps of wisconsin. If/when fossil fuels become less freely available, soil and water land will be worth much more than adjacent land with poorer soil and water. My girlfriends dad lives near Mississipi River near Minneapolis and has 10 feet of topsoil in his apple orchard!!!! Would take a while to deplete that. Good luck in your search. Shoot me an email on what you find as Im doing similar searches myself...

Also, I would shop for good neighbors right up there with soil and water, etc. (though this is not such a transparent commodity)

IF you can't find it or someone else does not post the link to the 4000+ on-line old ag book collection, I'll dig it up.

Other rabbit holes for you to go down:

Hi brix gardens

The australian soil and health archives (has sir howard's works)

The works of the soil food web group

Aceers USA/Rodale group

Spend some time with fungi perfecti (Stammets)

And lastly - be aware of the arguments of the pro rock dust crowd.

Andy,

Depending on your location, UW River Falls has quite a lot of information on soil/sustainability and is even hosting a conference in January. It's geared toward ag professionals but anyone can attend.

http://www.uwrf.edu/pa/2007/0712/1207072.htm

Thanks Folks,

I have noted the links and will begin to dig through the info this vacation. I'm looking in Eau Claire and Chippewa Counties (WI) and will see what info is available locally. The best thing I've found so far is the Web Soil Survey Tool

http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/

This tool lets you select a region of interest (ROI) and overlays soil types on some excellent aerial photos.

Soil choices are quite limited however, within commuting distance to Chippewa Falls.

Cheers,

Andy B

Andy - I'd really suggest that you talk to the extension agents in the areas where you are looking. I grant that most of them are production ag oriented. But I know a number of them in where I live and they are all really good people who want to help...even the homesteader.

One thing I would do is clearify in your own mind what you want to accomplish, i.e., fresh eating vegetables, storage vegetables, animals (and why). In other words, it will help them if you have a "business plan" so your discussion focuses on what you need to know.

Todd

My wife has been by the local USDA extension office and they gave her the Eau Claire county soil survey for free, with beautiful aerial plates and much background info. I will take your suggestion and stop by once I have done a little more research on my own. Most of the farms here are hay and dairy, though that may be because dairy is more lucrative?

My initial plan would be to start fairly small with a large intensive vegetable garden (I have some nice raised beds now in my backyard), chickens, and a couple of goats. Concurrently I would like to begin cover cropping and experimenting with some grains (barley, oats, wheat?), mainly to build the soil. Eventually in a few years time I would like to have a small sustainable farm, maybe even for local market. But foremost a more self-sufficient, productive (elP) lifestyle. I have been gardening for years and now help out on a local organic farm a dozen or so weekends per year - which I enjoy greatly. I don't know if I could handle their workload though, and they are in their 50's.

Regards,

AndyB

A simple answer to your question.

You must have good soil. If not your going to be wasting huge amounts of time and energy. Best to first find a good soil type, search the USA for where its at. Go there and check it out.

All the data is available.

Why Wisconsin? Why chose an area thats not suitable?

You need good access to good water. Good soil. Good growing seasons. Perhaps some wooded areas that are not just trash trees. Good hickory and oak. Good hardwood for heating and cooking. Land that drains well as bottom land can kill you.

Not too rolling either. Gradual is fine. Totally flat is not that good. A high water table can be bad as well.

You will also need some soil samples and check if it has a hardpan layer,called I think a 'fragipan'.

Springs are nice to have around. A good clear flowing creek is nice. A good pond or two is even better. A well that is not polluted.

Airdale,

I am quite disappointed to hear you say that farming in WI is a waste of time and energy. The farm I help out on south of Eau Claire here has totally denuded sandy soil, from years of chemical corn farming. They have a beautiful farm though, but mainly they raise chicken broilers. They have horses and goats (and other paying jobs) and we work hard to spread their manure on the vegetable fields in the spring.

Leaving WI at this point just doesn't make sense for me. I am lucky enough to have a good paying job for the moment and a daughter in high school. I would like to build up the farm infrastructure while I am still earning money and not too old - not waiting until my retirement or inevitable layoff. We are also tired of moving around the country following work and very much like the people we've met here in WI. There is ample freshwater here, low population density and a farming culture in place here already. No place is perfect, but if people here at TOD tell me that I am wasting my time on Billett sandy loam or Plainfield loamy sand then I will probably heed their advice. I was hoping that cover cropping for a few years and maybe adding terra preta (effectiveness on sand?) or rock fines as suggested, would help somewhat. I know it has been very hard to build the soil up at the farm I work on near here, but they have enjoyed some success. Woodlands here are mostly oak, birch, white pine in sandy wash areas and other trees I don't know. Maybe only really suitable for longterm sustainable grazeland farming - low density per Gene Logsdon?

Soil CAN be improved, with work. Neighbors are more important, and cannot be improved, easily.

While I agree that I cannot change my neighbor's behavior, I do think that mutual cooperation will become an essential survival trait among neighbors in a post-peak world. Once you've headed down the "pure defection" path it is hard to reconcile and make amends, but there will be a strong incentive to work together to ensure survival.

With today's market economy and the "false consciousness" it creates separating interested parties, natural cooperation is less important among neighbors, but I hope that will change as more direct and frequent barter interactions occur between individuals. That is my hope anyway.

Andy B

Airdale,

I am quite disappointed to hear you say that farming in WI is a waste of time and energy.

To be dissapointed you would have to value what he's had to say.

Go read EVERYTHING he's had to say. Notice the parts about 'survival off of forest forging' and how hydrinos are real.

He's right - even when one can quote other sources showing Airdale is wrong. For people to be successful somewhere else means he might have made a poor choice (and be extension be wrong)

here at TOD tell me that I am wasting my time on Billett sandy loam or Plainfield loamy sand

While plenty of TODers know alot - having a group of people tell you some land sucks while never having seen it.....why would you believe that?

There is ample freshwater here,

Water you can get to, pump, and is not full of toxins may very well be more important than anything else.

longterm sustainable grazeland farming

Is your goal to make farm-based products to export, or just feed yourself/family? If it is feeding yourself - farm animals concentrate organic matter you compost then add to your garden may be your best plan. Alfalfa will take sub-soil minerals, bring them up 50-75 feet to the topsoil (like trees leaves) so you can feed that to your critters, make green manure, or chop/boil and make a human-grade green tofu like material.

Hey Eric,

Since I'm relatively new here and I'm curious, exactly what is this anti-Hydrino bias you have all about ?

I'm mean, since we don't have a unified physics theory and all.

Your right of course - I should learn to trust my own experience and judgment more. TOD has provide such an incredible wealth of prescient information and analysis that it is easy to get carried away by the aura of omniscience. New Year's resolution - think more independently.

My goals are as you state - mostly to feed myself and family, but hopefully to be able to produce some food for market to help offset taxes, etc. I'll look into alfalfa, but up north here it doesn't grow as well because of the lack of dolomitic limestone found in the southern part of the state. I would probably need soil amendments.

While this is an interesting analysis, it oversimplifies in one important respect: People don't neatly fall into "farmer" and "non-farmer" cubbyholes. In particular, there are two intermediate categories that also must be considered:

1) People primarilly engaged in farming, but that also engage in some non-farming employment. They must do this to make ends meet, otherwise they wouldn't be farming at all.

2) People primarilly engaged in non-farming employment, but that also grow some food on the side (mostly gardening, and maybe some small stock raising). (I'd put myself in this category, quite a few others here on TOD might also place themselves here.)

The lines between these two categories are not hard and fast, though it is actually pretty rare to find someone that is maintaining exactly a 50:50 mix; most people lean to one side or the other.

In the US, at least, I suspect that some people classified as "farmers" actually fall in that first intermediate category above; it is getting pretty hard to make a living doing nothing but farming, and quite a few farmers do need to have something else going on the side, at least for part of the year.

It used to be that a very substantial portion of the US population would have fit into that second intermediate category. I would venture to guess that in a place like Russia, where many city and town dwellers work an allotment in a community garden, it probably represents well more than half the population.

My point is: As things pan out, it is not going to be the case that non-farmers are suddenly going to become farmers. That is a good recipie for starvation. No, what is going to happen is that increasing numbers of people that formerly grew NONE of their own food are going to start growing SOME of it; they are not going to give up non-farm employment, but will need to supplement their earnings with home-grown food to make ends meet. As this trend progresses, some people will become good enough at raising crops or livestock that they can buy small holdings and get into growing food in a more serious way; they'll still need something going on the side, though, to make it work financially. Finally, as some of these people become more successful as farmers, and as the demand for locally-produced food becomes more urgent, some of them will take the plunge and get into farming in a big enough way for it to become a full-time occupation.

This transition will require a couple of decades, maybe, but probably not much more than that.

The United States cannot afford any more farmers. We already pay the 2 million farmers $50 billion in subsidies. If we had 50 million farmers, that would be $1.25 trillion! If you think that the government prints too much money now, just wait until you get more farmers, all of them with their hands out.

The United States cannot afford any more subsidized "farmers"

A better metric for the graph would be "% of productive work time devoted to agriculture" for the country as a whole. But I doubt such data exists...

I am not sure how to respond to the comments about data quality and definition of "farmers." I am aware of the difficulties applying the term and so my initial thought when doing the analysis was that it would possibly be absurd. When the relationship actually stood out I was pleasantly surprised.

But, I may show something else on a future post that brings up some issues regarding the accuracy of census data.

Hey, it's really a no brainer. One farmer with two horses can produce a cash crop of cotton or something else, then enough food to feed his livestock and perhaps one or two other families. One farmer with an eight row tractor and all the mechanized farm equipment to go with it can produce enough food to feed at least one hundred families.

Why is there even a question here? The green revolution is a direct product of all that extra fossil energy. And all that extra energy means a lot more food. And all that food means a population explosion.

Ron Patterson

I suppose the key question is can we feed 300 million plus with declining fossil fuel inputs? I think that is where the Victory Gardens and farmettes come in.

I think it more likely that the US will simply stop sending food abroad and confiscate the energy required to continue industrial farming.

The famines abroad will simply not be televised.

We can, but maybe not at 3500+ Kcal/day, and maybe not with beef being what's for dinner very often. You are right that Victory Gardens (including replacing most lawns with potatoes or something), and smaller scale ag surrounding most cities and towns, will be absolutely essential.

Thanks for great article.

I was many times thinking how to estimate a EROEI for the whole country and society. I came to a feeling that the fraction of the population, which is directly active in the agriculture activities, has to be related to it.

Your graphs are only supporting my thoughts. Prior the industrial revolution there were at least 80% population always active in the agriculture despite of historical time and continent.

This estimation based your graphs is indicating that EROEI is at about 50 in US and most developed countries and barely above one in such countries like Ethiopia. It seems to be in agreement of estimation of EROEI done by other means.

M

Here in Iowa a switch to locally produced biodiesel would not be that difficult. Farm equipment that uses gasoline is limited to antiques. Farmers almost exclusively use diesel even in their pickup trucks.

There are a few changes that would be a big help in keeping the young folks down on the farm.

1) Eliminate property taxes. No more losing land to the taxman. This 11th century relic has no place in the 21st.

2) Universal single payer health care. The self employed simply cannot afford health care costs.

3) Let farmers borrow borrow money at the Fed discount rate. No more having bankers make more profit on a bushel than the farmer. Unlike the paper wealth of Wall St farmers actually create real wealth from the combination of their labor, use of natural resources like sunshine and rainfall, and their ingenuity.

4) Use the surplus biomass farms create as a replacement for some of the coal now used to generate electricity. This would create a new product from farmers at no extra cost to them.