Economic Impact of Peak Oil Part 2: Our Current Situation

Posted by Gail the Actuary on September 25, 2007 - 9:45am

This is the second of a three part series giving my view of the economic impact of peak oil.

Peak oil seems likely to make a huge change in our economic system--more than would be expected by a worldwide decline in oil production by a few percentage points a year. In Part 1, we looked at the contrast between economic systems before the industrial revolution and the current economic system. We also looked at economic studies that suggested that energy, and the more efficient use of energy, seem to be big contributors to the real economic growth that took place since the industrial revolution.

In this segment, we will look at some other changes affecting the economy besides the growth in the use of fossil fuels. We will look particularly at debt and how peak oil is likely to affect a financial system that is tied to debt. We will also look at some the stresses that the economy is currently under. Some of these stresses seem to stem from a failure of the United States to fully adapt to its own decline in oil supply since 1971; some of these stresses come from the fact that the world is finite, and we are reaching the earth's limits with respect to more than just oil.

1. Why is debt important to our economy today?

Debt, and the trust that makes debt work, is the glue that holds our economy together.

There is a very close relationship between debt and the supply of money. When a person borrows money from the bank, the loan actually increases the supply of money available. When more and more people take out mortgages and other types of debt, the people taking out the mortgages end up with more house then they would otherwise have. When homeowners refinance their homes and take the equity out, they get additional cash that they can spend on other things.

If we suddenly have a situation where there are many defaults on mortgages or other debt, we end up with a reverse of the above situation, so that there is in fact less and less money. If a bank takes possession of the house when a purchaser is behind on payments, and tries to sell the house to get its money back, the house is added to the large inventory of other unsold houses. This tends to bring the prices of houses down further, and tends to reduce the amount of equity other homeowners have in their homes.

Besides this role of debt, debt (in the form of bonds of various types) makes up a large share of the assets of insurance companies, pension funds, and banks. If there are suddenly many defaults on debt, most of the financial institutions in the country are at risk.

Debt is also a means of smoothing financial transactions. We use credit cards for personal purchases. Businesses make purchases from other businesses, and are often given some specified period to pay (say, 30 days or 60 days), before interest starts accruing. This is a form of debt. Because the US has a trade deficit, there is debt associated with purchases we make abroad. If we buy a car from overseas, on average, there are not enough exports to balance out our imports. Japan (or whoever is selling the car) ends up with more cash than it can use for imports. It often takes its excess dollars and buys US Treasury bonds--another form of debt.

2. How did we get to a situation where debt is so important to the economy? Weren't panics and crashes (like the bank failures during the depression) between 1800 and 1932 so disruptive to the economy that debt could only play a minor role?

During the time when panics and crashes were frequent, it was difficult to use debt widely, since defaults were a major problem. A number of changes were made over the years in an attempt to provide stability. The indirect result of these changes was to make greater use of debt possible. (Increased use of debt was also enabled by going off the gold standard in 1971, since the money supply was no longer tied to the amount of available gold.)

Factors which contributed to the stability of the system included:

• Establishment of the Federal Reserve System in 1913. This acts as a central bank, and tries to regulate monetary supply, primarily by adjusting interest rates.

• Establishment of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in 1934. The FDIC insures deposits in banks and savings and loans up to a specified limit (now $100,000), to prevent runs on banks.

• Establishment of rules for international financial relations at the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, including the establishment of the International Monetary Fund in 1945.

Another factor adding stability to the system was the economic growth that came through the growing use of fossil fuels.

3. Why would economic growth--pushed along by growing fossil fuel use--make the debt system more stable?

The reason that economic growth makes a debt system more stable is that we are dealing with a system in which a person (or company or government) borrows money at one date, and pays back that money plus interest at a later date. If the economy is growing rapidly, incomes tend to be rising, making the payback of loans, with interest, easier. A person who has taken out a home loan, or a loan for college expenses, will find that his higher income over time makes debt payments relatively affordable. Default rates tend to be low, so interest rates can be relatively low.

If there is no real growth (that is 0% economic growth), there will still be a few situations where loans make economic sense. These projects will have a good enough return that borrowed money can be used, and the return on the project will cover the interest on the loan. In general, the process will not work very well, however. Real incomes will not be rising fast enough to provide a cushion to make interest payments more affordable. Default rates will be quite high, so lenders will need to charge a higher interest rate to cover defaults. This will make loans affordable only in fairly rare circumstances.

If we get to a situation where there is long-term economic decline, rather than growth, debt becomes a losing battle. Default rates are likely to be very high, making required interest rates (to cover expected inflation, a "rent" payment on money, and expected defaults) extremely high. Virtually no project will have a high enough expected return to be financed by debt in such an environment.

4. Where do we stand now with respect to economic growth?

Wikipedia tells us that income per capita was essentially flat until the industrial revolution. Between 1790 and 1946, Economic History Services data shows that the US experienced long term economic growth. There were a lot of ups and downs, related to the bubbles, panics and crashes that were so much a problem in that era, however.

Since 1946, Economic History Services data shows that the US real growth has been about 3% per year. Year to year fluctuations have been smaller than prior to 1946, due to the changes described in Question 2 and the interventions of the Federal Reserve to maintain stability.

Going forward, it seems very probable that the US real growth rate will decline once world oil production begins to decline. From Part 1, we know that there is a close tie between energy use (and more productive use of energy) and economic growth. We also know from Part 1 Question 6 that productivity growth at this point is relatively small - only 1% or 2% per year, so that we are unlikely to make up a very big decline in supply by efficiency gains.

Surprisingly, a decline in US real growth rate may come even before peak oil. The issue is really one of how much oil is available to the US, through its own production and through imports. If something happens to reduce our imports, such as a drop in the value of the dollar, or greater competition for existing supply, we could find ourselves with less oil, even before the world reaches peak oil. If the decrease in oil supply is large enough that we cannot make up the shortfall by other means (increased coal or biofuels, for example), we could face declining real growth on a long term basis, even before peak oil.

5. Wouldn't declining economic growth cause problems in an economy that is as tied to debt as ours?

Yes! I It is likely to cause a lot of problems.

If no intervention is made, there are likely to be a huge number of defaults. This will lead to many insolvencies and deflation, most likely.

If steps are taken to guarantee the payment of loans, this may lead to hyper-inflation. We may still have our bank accounts and pension plans, but we will find that the funds in them will purchase much less than in the past.

It is possible that there will be such serious disruption that the monetary system as we know it disappears. We could temporarily end up with barter as the primary means of exchange. Presumably, an alternative monetary system would be developed fairly quickly, but it could still be quite different from what we have today.

New agreements with trading partners to facilitate inter-country trade would also be required. These new agreements could prove to be a more difficult problem than developing a new monetary system for use within the country.

6. Hasn't planning been done that considered the possibility that over the long term, economic growth may not really be possible?

No. Economic theory has grown up since the industrial revolution, during a period of long-term economic growth. Recent economic work has been done using data since World War II. No one has stopped to think that the analysis period data might not be typical of the situation over the long run.

Some examples of calculations that are distorted by looking at data from only periods of economic growth include the following:

• Pension calculations. Much higher contributions will be needed, it economic decline is expected.

• Loan calculations. A much higher margin for default is needed in interest rates, if a decline in economic growth is expected. Thus interest rates on loans will be higher.

• Projections of stock market values. An analysis that considers only periods of economic growth will show good prospects for stock market growth in the future. An analysis that considers the possibility of long-term economic decline will show declining values.

• Models used by quantitative analysts to price derivatives and sliced and diced bond funds. It is not clear that these models are very good in the best of circumstances. If one adds the major shifts caused by declining economic growth, rather than increasing economic growth, the models are likely to be hugely distorted.

7. I have heard that the US has been spending more than its real income in recent years. It seems like this will only make the problem of a future decline in real income worse. In what ways are we overspending?

There are several ways that we are spending more than our real income:

• We keep adding more and more debt (personal, business, and governmental). We use debt to finance our expenditures, with the idea that our income will be higher in the future, so we can afford to pay for our expenditures plus interest later. One example of this is refinancing home loans, and using the equity to pay for current purchases.

• The government has developed programs like Social Security and Medicare that promise payments in the future, that are only partially funded today.

• We defer maintenance on our infrastructure - roads, bridges, pipelines, and electric grid, for example.

• We are depleting our non-renewable resources. Besides oil, we are depleting our natural gas, so that declining production is expected in North America in a few years. We are also using water from our aquifers more quickly than it can be replenished, and we are depleting our soil by not returning enough organic matter to it.

• Debt payments are artificially low,

• We are importing more than we are exporting, resulting in a growing balance of payments deficit.

8. I'd like to know more about the last two points. Tell me first about the US Balance of Payments situation.

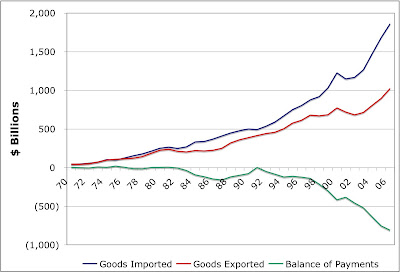

US oil production began to drop in 1971, and the US went off the gold standard the same year. Since then, the US has been importing increasing amounts of oil and other products. This increase in imports has not been balanced by an equivalent increase in exports, so our balance of payments is getting more and more lopsided.

Figure 1: US Balance of Payments, 1970 – 2006

What is happening is the US standard of living is increasingly being subsidized by the deteriorating balance of payments. In 2006, this deficit amounted to about $2,700 per US resident, or somewhat more than 10% of US per capita income. This deficit relates to a wide range of products --only about 15% of our imports are currently petroleum products.

US trading partners are becoming increasingly unhappy about this situation, partly because they realize that they are financing a lifestyle Americans cannot really afford. In addition, many trading partners are becoming aware that world oil production is likely to decline in the next few years. Peak oil is likely to result in declining real GDP and a much greater chance of default on debt. Our trading partners do not want to be caught with a lot of worthless debt.

9. What about the other point in Question 7, "Debt payments are artificially low"?

There are several reasons debt payments are artificially low:

• Foreign trading partners in recent years have been using the excess cash they received from the US purchase of imports to buy US debt. This has helped to keep interest rates artificially low. This issue is closely tied to the balance of payments situation above.

• Low interest rates set by the Federal Reserve have also tended to keep interest rates low.

• Some new debt products have artificially low teaser rates for the first few years they are effective.

• The charges required for defaults on loans have been calculated in a period of economic growth, so are artificially low.

• Underwriting of loans has often been very loose.

If payments on loans are artificially low, lenders will generally fare poorly. Such a situation is not sustainable--In the long term, debt payments (on all new loans and some existing loans) are likely to rise, resulting in market contraction and defaults.

10. Are there problems with the debt system, over and above the artificially low payments that may cause defaults in the future?

Yes. Confidence in the system is being severely tested. One of the basic characteristics of a debt-based finance system is that there must confidence in the system for it to continue to exist–-otherwise lenders will stop granting credit and the system will come to a screeching halt. For example:

• Debt products have been put together without adequate concern for protecting the lender. Home loans were made with initial teaser interest rates and little down payment. Commercial loans were made without proper covenants.

• Questionable loans were repackaged (after being sliced and diced) and resold around the world. These repackaged loans cannot be valued properly, partly because of the questionable nature of many of the underlying loans, and partly because the valuation system that was planned (using rating agencies and theoretical models) works very poorly in practice.

• Off-balance sheet financing of banks makes it impossible to assess a bank's true financial situation. Banks are becoming less willing to lend to each other, because they cannot tell what each other’s actual financial situation is. Banks lending to other banks are not protected by FDIC coverage, so they are concerned when there may be a risk of default.

11. What other issues are currently on the horizon?

The world is finite, and we are reaching its limits in many ways. Besides energy-related impacts discussed in Part 1, there are many others:

• There is increased competition for soil and fresh water. It is not easy to increase production of biofuels, because of competition with food production. Costs of food and other products tend to rise with scarcity, adding to the overall pressure on consumers, and pushing real economic growth downward.

• Many minerals are becoming harder and harder to extract, because the locations with high concentrations have been mined. The real cost of mining these minerals is rising, both because of the higher cost of fuel and because of the additional work required to extract these minerals.

• Climate change is becoming a serious issue. There is a significant possibility that climate change will disrupt food production in not many years. There is also a possibility of coastal flooding causing significant damage.

12. How would you sum up what we are seeing here?

We are facing a world that is already stressed - by a debt market that is not working well, by pressure on limited resources, and by climate change. In such a world, it does not take much of a change to disturb the debt system, and to cause serious problems with the world monetary system.

Peak oil, or even the squeeze preceding peak oil, is likely to result in a decline in real growth. Even a slowdown in growth might cause a problem at this point, given the existing problems in the system. This disruption of economic growth is likely to put pressure on the monetary system, because our monetary system is tied to debt, and debt is easily disrupted by declining economic growth.

The United States is particularly vulnerable to problems because we are living beyond our means and because we are already straining our debt-based system to its limits. There is a significant possibility of a discontinuity of some type--either deflation or rapid inflation. There is even a possibility that our monetary system will fail completely, and need to be replaced.

The long period of economic growth in the past 60 years has lulled analysts of many types into believing that the favorable patterns associated with economic growth will last forever. It is pretty clear that these favorable patterns are in fact temporary. Peak oil, or the squeeze preceding peak oil, is likely to result in a rapid change in the financial situation that may have more impact than the decline in oil production itself.

In Part 3, we will look at the changes that are likely to occur in the years ahead.

Pay off your debts, make practical preparations. Thereafter if you have any surplus savings left exchange them to the only real money: GOLD.

The fiat money systems are likely doomed at least to further depreciation year after year ahead.

RE the gold standard: IMO the US dollar's link to gold had long become a fiction by the time France 'called the bluff' and actually began demanding payment in gold. The pros and cons of a gold standard have been debated extensively on this list and elsewhere. I don't see a way that a gold standard can realistically work. But then, I don't see a way that the worlds current economic situation can work regardless of the commonly accepted monetary standard. We are in a bad fix.

OIL AND MONEY

Hello TODders,

As an economics neophyte you might ask:

1. What is "money"?

2. Where does it come from (how is it "created")?

3. Why does our culture need ever-growing supplies of money (and the goods/bads, services/disservices to back up that money)?

Similarly, a PO neophyte might ask:

1. What is "oil"?

2. Where does it come from (how is it "produced")?

3. Why does our culture need ever-growing supplies of of flowing oil (and the goods/bads, services/disservices dependent on that growing flow of oil )?

OIL and MONEY: How did we get on this accelerating treadmill and where is the button for stopping and getting off?

A good video http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-9050474362583451279&hl=en-CA

Paul Grignon's 47-minute animated presentation of "Money as Debt" tells in very simple and effective graphic terms what money is and how it ... all is being created. It is an entertaining way to get the message out. The Cowichan Citizens Coalition and its "Duncan Initiative" received high praise from those who previewed it. I recommend it as a painless but hard-hitting educational tool and encourage the widest distribution and use by all groups concerned with the present unsustainable monetary system in Canada and the United States.

It's a great video but the arguments at the end about why the system is unsustainable aren't correct. Look below for the reasoning as to why.

Rajiv,

The punch line near the end is that hardly anyone gives a second thought as to what money is or how it is created.

I think if we took a survey, as some of us do, of how many people ever give a second thought to what oil is, how it is created (formed and extracted) and why it might be an essential element of our very existence, the results would be very similar.

The "rational" human mind doesn't give it a second thought. Second thoughts hurt. Best to leave such painful thinking to the invisible smart people who are taking care of things --the care takers and crude givers. :-)

http://politics.reddit.com/info/2sxcg/comments

if you are so inclined to promote this piece around the web, we would appreciate it.

All money is created as debt, as is easily understood after viewing Money as Debt. You're almost there but hesitant to say it, or so it seems. If we all pay off our debts, there's no more money. It is really that simple.

The first task of the Fed is to maintain the value of the US dollar. It has lost some 95% of its value since 1913, so that is definitely not working. Saying that the Fed "tries to regulate monetary supply" could mean anything, from overflowing the markets with debt-ridden funds, as in the past decade, to suddenly withdrawing lots of money, as it did in 1913, and, in my view, soon will again. For whom does the Fed work? The American people? It's a taboo question, but perhaps not a bad one.

You use terms like "real growth" and "real GDP" as if these are knowable. They are not. For all we know both may have been negative for years, a possible fact hidden by -exponentially- increasing money supplies, aka debt.

One thing you haven't touched upon is what Henry Liu called:

The rise of the non-bank financial system. That is, the debt instruments issued by institutions other than banks. These instruments have allowed the rise of the derivatives industry, which at their present estimated value (sic) of close to $500 trillion have the potential to bring down the entire existing global financial system.

Derivatives are far more important than homeowners defaulting on loans, both because of the much bigger numbers involved, and because underlying assets have been leveraged to a far higher extent. The world has never had anything remotely like them, which makes it hard to oversee, but all governments, banks, pension plans etc. are deeply invested in them, and that is scary.

It is tempting to try and see a link between peak oil and the economy, but it's not very clear so far in what I've read here. I doubt the causality of the link very much; the financial system is imploding on its own accord, in my view. Allowing the creation of 100-fold leverage on any asset one can think of is an insanity that could not even be balanced if we had 10 times as much oil as today.

One last thing: oil prices seem to be on the rise these days, but are they really, or are we fooling ourselves? For instance, did they rise in Euro's? Can't be much. Could that be why pump prices are still relatively low? Nobody addresses this, might by a US blinder kind of issue. The dollar just reached another all-time low vs the Euro.

I couldn't find a Euro chart offhand, but this one should be cause for pause when discussing oil prices:

Brent Spot/dollar commodity charts

- development last 3 month(s)

Thanks for saying it for me. The inflation that you blame on the fed is to an extent necessary; the prospect of cash depreciation is a goad to invest rather than hoard, and 3% is considered sufficient motivation. This keeps the cards on the table and moving. Compounded over time, we shouldn't have a loaf of bread or an hour of work be the same as 1910, but the reality has been not a smooth curve but a lumpy one. Nuther lump coming, but is it up or down?

We may see the fall of the non bank financial system, and much faster than its rise, as is common in the sawtooth world of such things.

P, I don't know where that idea comes from, but it's pretty wild. A quick look at exponential functions says it's doomed from the start. It simply forms the basis for a consumer society, I would think, and that's not going very well.

As long as people have not fulfilled their (basic) needs, they will spend in order to do so. When they have, why entice them to spend more? As all money is issued as debt, they will only get deeper into debt, so who benefits from that 3% inflation? Not the people.

It will bring down the banks as well, or at least I can't see how it couldn't. The entire system is neck-deep invested in derivatives.

Then there is the obvious connection to a growing population. Picture a village with a fixed number of people and you could conceive of a steady-state economy with no inflation. Keep adding people and this triggers all the other pressures to adopt 'inflationary' systems such as resource extraction and fiat money. Population expansion must, I believe, be seen as the fundamental driver behind expansionary economics.

No it's not. In periods with very low inflation or even deflation like around 1900 other mechanisms were used to achieve the same effect, for instance the Woergl stamp scrip. This currency was used to rejuvinate a small city and it worked by causing money to "rust" by forcing people who held the cash to pay to keep it valid.

This practically forced investment and usage of the money rather than hoarding, as people are wont to do when a currency is deflating. It had an amazing affect on the town, by all accounts.

These days inflation is used to achieve the same thing. Rather than sit on piles of cash waiting for them to get more valuable, people invest. They do this even if they don't realise it - by holding their money in savings accounts or pensions.

It's widely accepted that a small amount of inflation "greases the wheels".

Why entice them to spend more? Perhaps because people spending money is how things get done? If everybody bought only the minimum they needed to survive and hoarded the rest our civilisation would grind to a halt. Nothing new would be created, infrastructure would decay, our society would become a pathetic joke.

You want money to circulate, you want investment. What you don't want is too much new money entering the system because that can cause nasty feedback loops.

Also, whilst it's true that the money system is based in "debt" that's not necessarily a bad thing. The word has many negative connotations, but having money be issued via bank loans has both pros and cons when weighed against alternatives (like full reserve banking or Ripple-style mutual credit systems).

Why entice them to spend more? Perhaps because people spending money is how things get done? If everybody bought only the minimum they needed to survive and hoarded the rest our civilisation would grind to a halt. Nothing new would be created, infrastructure would decay, our society would become a pathetic joke.

Sounds like a prescription for exactly what we need. (although, I do believe our society is already a pathetic joke for holding on to growth as one of its core values)

Anyone touting inflation as a good thing doesn't understand exponential functions.

Inflation does one thing only: it depreciates the value of your assets, while debasing the value of your currency.

And you wish to make the point that that is a positive thing, and our civilization would even grind to a halt without it.

That may be true for a civilization based on American Idol, McMansions and Cheese Doodles, but why would we wish to save or maintain that? Aren't the limits sufficiently clear yet? How much longer will it take?

Of course. if what you have loses value all the time, and what you need gets more expensive at the same time, you will have to go and work and dig holes and what not, in order to make up for that loss, and you'll get mighty active, but that’s good for who exacttly? For you? Who do you think collects as profit what you are losing?

The early 1900's are not a case pro inflation, they were a time where an inflation based economy was showing the same cracks that we see around us now. Fight the evils of inflation with more of the same. Real promising.

.

Inflation ultimately can only destroy societies. And my, look around you.

Inflation reduces the value of currency, which makes sustainable investments more compelling.

Consider a forest that I own. If there is no inflation ... if there is deflation, in fact ... then it's in my best interest to clear cut the forest straight away. I'll get a lot of money up front and that money will become more valuable year after year! But if there is some mild inflation, then it's in my best interest to run the forest sustainably, because I get a guaranteed income each year (the price of wood will rise along with the price of everything else to match the increase in money supply). In other words I invested and produced value rather than hoarding currency and eliminating value.

You're right that inflation can destroy societies - just like deflation can, if allowed to get out of control. Your position on the early 1900s don't make any sense - the Great Depression was a time of deflation, not inflation.

I believe that ilargi was referring to

You seem to be fixated on 1929. Before 1929 but still very much a part of the early 1900s (part of that same 20th century), we saw numerous financial events that demonstrated the hazards and folly of inflation.

"The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function." -- Dr. Albert Bartlett

Into the Grey Zone

While I understand the point Mike was making, it does provide a valuable counterpoint: The way in which this forest is *considered* is from a purely economic standpoint, and that's the tragic rub of our whole economic way of life -- EVERYTHING is reduced to its pure economic value regardless of any other value ethic!

IMHO this all encompassing capitalist economic meme is our ruination as a species. We need a land ethic that supports our basic communal ecologically based survival needs first and foremost. In other words, the forest is valuable as an intact healthy ecosystem that supports our life and all the other living things that contribute to the same! As soon as we diminish this land ethic valuation and substitute it with an economic one we devalue and diminish our own survivability.

Hence the lesson we are soon to learn as a species: Nature does not make economic compromises with anyone!

1. What is economy but the mathmatical analysis of scarcity of resources?

2. Why are you considering an entire math science to be "bad" just because humans used it to understand better how to destroy Earth? Economy isn't bad and that's the issue we face. The problem is that it worked too well, not too bad.

3. Isn't morality only a traditional-based "economy" of things? We all have learned by moral that we should be in more of a harmony with the environment (the greens), but isn't that a purely economical stance of sustainable existence? Aren't you confusing "Economy" with "PR using economical terms to rape the Earth"?

I'm not against what you're saying. I'm against the way you're saying it. The program you present (get the ecological issues back to politics, aka society, from the economics) has some problems, but essentially I agree with it. Society should decide what is best for the ecossystem first, and only thereafter what is best for particular economies.

But this kind of thought will be referred to as "communist" or "extreme left nugget thinking", and so I wouldn't bet on it.

I'm sorry but I do not accept your definition of "economy" as a "mathematical analysis of scarcity of resources." I do believe this is way too narrow a definition of what should constitute a healthy and life sustaining *economy* and our understanding of it.

Secondly, I did specify the particular economic analysis system I was referring too: "all encompassing capitalistic" one. Your suggestion that I was inferring all economic (or math based) analysis "bad" is a misguided interpretation of your own making.

However, as to your suggestion that such an economy as you conceive it, as a mathematical abstraction, "worked too well, not too bad" in *destroying the earth* only serves to prove my point!

Without an ecological ethic (or however else one wants to call it) to guide us, all our scientific and mathematical genius can not save us from continually doing harm via these lofty methodological abstractions -- they need to be grounded in earth based limits and our acceptance of them. In short we need to accept that we aren't demi-gods over this earthly creation but mere caretakers, and very ignorant and fallible ones at that.

Finally, I don't care what anyone may think to negatively label such thoughts as representing. We don't have as much choice in this matter as we pretend we think we do and/or will have. The way we are going about accounting the economy of the world is without a doubt leading us to ruin. Ultimately, earthly reality and the very real limitations that rules the natural world here and within ourselves will prevail over our ecologically unhinged abstract economic conceits.

Whether we make amends before our civilized destruction is complete is *the bet* we are wagering and it is the only one none of us can predict with certainty, but make no mistake we are betting against ourselves daily with our unethical economy as is!

Thus my assertion stands: Nature does not make economic compromises with anyone!

Mike Hearne:

If the Woergl stamp script worked so well, then why wasn't it revived during the Great Depression at least in Woergl? Why are there no more examples of this system working in the years after this one experiment?

When I'm looking at an idea for an oil well one of the first things I look for is evidence that other people or companies are doing a similar type of prospect.Its confirmation that my idea isn't too outlandish. And its the same with other ideas, I don't mind being fairly original but if I'm too original its not a very good sign. Bob Ebersole

Bob,

Democratic forms of government were invented by the Greeks several hundred year before Christ. After a relatively brief period of experimentation these forms of government disappeared from the world for over a thousand years. Did this disappearance constitute 'proof' that democracy was a bad idea?

And, by the way, the Woergl was deliberately suppressed at the request of the Austrian central bank. The case was fought up to the Austrian supreme court which ruled in favor of the central bank. What a surprise.

Roger

Peak oil guarantees that any debt based system that depends on infinite growth is doomed. So by itself, peak oil guarantees our current monetary system, even without the non-bank financial system, is doomed.

Our current system has so many deficiencies that it seems to be doomed, with or without peak oil. I agree that the non-bank financial system is a big part of the problem. It seems like the whole system will collapse fairly soon. Any push from oil prices, or the drop of the dollar, or knowledge of peak oil, will only help it along.

When I started trying to tackle this subject, I found myself with too big a topic to handle. I divided the subject up into three posts, but even these got long. I stayed away from the non-bank financial system because I needed to contain the topic somewhat. Perhaps I can do another post later with some other issues. In this post, I do mention off-balance sheet financing of banks as one issue.

That´s why i maintain that GOLD is the only real money in existence. It ain´t debtbased and can´t be printed out of thin air. Sure you can´t go and buy milk for a gold piece, but its a sure thing for wealth preservation of ones hardearned savings.

Gold is ‘real money’ only in the presence of a healthy economic system in which relatively wealthy people exist who want to deck themselves out in gold trinkets. If everyone is worried about where their next meal is coming from or how they are going to keep warm this winter a whole warehouse full of gold will not be of much use to you.

Couldn't one say that about any good, be it a precious metal, mineral, commodity, or a chicken? They aren't debt-based and can't be printed out of thin air either.

What I'm nervous about is your use of the word "only". I would argue that there is a large basket of stuff that can be used to efficiently store value, and that picking a single one isn't wise.

Couldn't one say that about any good, be it a precious metal, mineral, commodity, or a chicken? They aren't debt-based and can't be printed out of thin air either.

Unlike other commodities, gold is not perishable, does not rust or corrode and takes very little space to store. 500 gold coins - which can easily fit in a small briefcase - can buy you a decent house in most parts of the US.

Also, gold has a 5000 year history as a store of value. I would argue that silver is also "money", but not as much as gold.

Of course. And that's the reason for my use of the word "efficient".

Diamonds would also qualify and have far better value density than gold. Many currencies would do the trick. I'm actually fond of land as a store of value.

In case it wasn't clear, my point was not that one shouldn't buy gold, but rather buy a diversified basket of assets to cover yourself no matter what happens.

Gold is a universal currency. I know I spend a lot of time in Asia. And yes you can but a litre of milk with gold. In fact gold is the prefered currency especially in Chinese communities. You can buy and wear standard weigh gold earings / sleepers in any pierce-able point on your body. The minimum is about 5g. They will even give you change. This is handy to know as you can buy or have made a large amount of these if you are traveling from say Thailand to China via indochina just as an example. It is also common in Central asia to use a chain you can cut links out of. I have done this in Tashkent.

Diamonds are no good as money. How do you value it? A goldcoin as a Krugerrand is recognised by almost everyone around the world, and are smaller more convinient pieces of value than diamonds.

My stupid opinion..........

For the average Joe Blow.

In the not too distant future, your labour and health will be your biggest asset.

Wealth eventually will be seen in land barons.

Livestock, farmland and the ability to defend it, will be all that matters.

Big land barons will be like the monarchs of old.

The worth of gold will be determined by how well it can keep you alive, if a gold coin can't buy your next meal then I would say it was worthless.

Initially labour will be very, very cheap. There will be enormous competition to provide it.

The inevitable crash in populations, will be the only pressure relief.

Paying for and providing security may be a growing trend.

The big problem with diamonds is that the price is far, far higher than their cost of fabrication. If the De Beers cartel falls apart, the price of diamonds will quickly fall to around the price of fabrication. Even in a world with scare fossil fuels, I'm sure diamonds can be manufactured for less than 1/10th the current market price.

I learned about the value of diamonds when I went to sell my mother's jewelry after she died, to help fund the estate (needed to raise money to pay bills). Furs older than three years old are worthless. You can't give them away. No one wants them. Furs older than one year, but newer than three years old have a value of about 1/25 of their retail price.

Costume jewelry is worthless, about $5.00 per pound.

"Gold-filled" anything is worthless. 18K to 22K gold is worth the melt value, anything less than 18K is worthless.

Diamonds are worth 1/10 of the retail value, if they are big enough (>1/10 carat). My mother's wedding ring, with an insurance valuation of $4250, brought $430.00. I checked this value on Ebay, and this is the general state of the market. Diamonds bought at retail are *NO* store of value. Diamonds at wholesale may be valuable, but unless you're one of the diamond traders, you aren't going to get a diamond for the true wholesale value.

Steuben glass is worth 1/10 of retail value. And so on. Mass-marketed collectibles are worthless (but check prices on Ebay, some of that stuff has deceptively high prices). Usually anything stamped "Made in China" is worthless. Silverware is worth the melt value. Make sure it's sterling, silverplate is worth the melt value of the copper which comprises most of it, unless of course it's more than 150 years old and has recognizable hallmarks from a recognized UK or Irish silversmith (same for silverware).

Stainless steel "silverware" is worthless

Land only works as a store of value where there is some authority that grants land rights and protects them. Without such a government (and note that not all governments protect land rights or even recognize them), your land can be alienated at will.

Silver is actually a pretty good place to park your money too, but it's big problem is storage. The price of gold (when calculated by weight) is almost 50 times greater than silver. Furthermore, a 1-ounce silver coin is larger than a gold coin of the same weight, because silver is lighter. So if you're storing silver coins for the coming disaster, you are going to need over 50 times the storage space. A large safe-deposit box could store over $1 million worth of gold, but only $20,000 in silver.

Of course, after the US$ collapses and you go to the corner gas station with a 1-ounce gold coin, it's going to be awfully difficult to get change. In that case, silver would certainly be better.

Sure you can store value in any tangible good. Bu if we talk about money, gold is and has been THE money for 5000 years around the globe. Why should it cease to be money now, come what may?

And it takes little space, is easily hidden and transported.

Cash is just a set of tokens valued by others. I think if you actually tried to live your daily life using only gold you'd be quickly disabused of the notion that gold is "real money" at least in the west.

Try to imagine going to the local supermarket, or gas station, and attempting to pay using gold coins. Do you think they'd accept? Or would they point out that it's a lot easier for them to understand the value of a $20 bill than a piece of metal which may or may not actually be gold (how many people have even seen a real gold coin these days?).

Another problem with using gold as money is that there isn't enough to go around and hasn't been for decades. It's also far more valuable as a useful material for things like semiconductor manufacture than it used to be. Hoarding gold makes no sense. I'd much rather try and buy things using IOUs in my local community than haul around easily-stolen pieces of gold!

"try to imaging going to the local supermarket, or gas station, and attempting to pay using gold coins"

I have never suggested that. As long as we have some kind of paper money working, you of course use it for daily purchases.

But the gold coins preserves the value even in the not so unlikely hyperinflation we perhaps are going to endure.

Then you exchange your gold coins now and then, whenever you need to a little more paper money for daily needs.

If you travel abroad, you can always have some goldcoins in your purse, for exchange to the local paper money.

If we have a collapse, and the paper money systems collapse. What do you think has more value; The old paper notes, or the gold coins?

Anyway, as i said in the thread before, you should first take care of other preps, and only buy gold if you have eccess savings left after the preps are made.

Once gold reached spectacular highs of $750/oz. only to be liquidated at $300/oz. a few years later. Some who trusted in gold to save them became greatly disappointed.

Some who trusted in the value of their real estate are seeing fortune dissappear before their eyes.

On the dollar bill it was written, "In God We Trust." One cannot trust the government in these times, rather that the government is doing all it can to dilute the value of the U.S. currency without producing favorable returns. Iraq is in its worse year of the war. Republicans indicated they were in Iraq to stabilize it, yet Iraq would have been more stable if they have never conned Americans into supporting the war in the first place.

Germany's banking system collapsed in the 1920s. Anybody want to tell us what that resulted in?

Cute blonde girls in waving cornfields.

I am sixteen going on seventeen.

Lots of them.

Cornfields?

I thought they were mountain tops with boom boxes tucked away in the corners to blast out the sounds of music.

(Vellcomin to my Cabaret. Everything is beautiful. The show girls are bea-u-tiful. The sounds of boots stomping is bea-u-tiful. Life is a Cabaret ole' chum.)

I presume, that all know what happened in the Weimar Republic at that time.

There is a story from that time of a hotelboy in Germany, who got a one oz goldcoin as a tip from an american guest.

The boy kept the coin, and eventually the hotel went bust. The hotel owner stood in the corridor and said out loud, that if he could get one oz of gold for the hotel, then he would sell it.

The hotelboy happened to stand there hearing what he said. He asked the hotel owner: do you really mean it? Yes said the hotel owner. Then i will buy the hotel said the boy and gave him the coin.

The boy managed to get the hotel on its feet again, and after the war he traveled abroad and founded a worldwide hotel chain. The boys name was Hilton.

So you see in some years you can perhaps at least buy a fine mansion for a few gold coins.

Nice urban legend, but this bio of Conrad Hilton doesn't back it up. It has him in Texas, not Germany, at the time of the great hyperinflation in 1923. Was it somebody else instead?

No it was not somebody else. It was just a nice urban legend. Why do you have to come and spoil it???

Gail,

I see a drop in the dollar as a very positive thing right now. It is a way to boost fuel prices while supply is also increasing. Since the US is doing little otherwise to control oil consumption, this gives at least a push in the right direction. With the building trade slowing, this will turn out to be a very good time for insulating existing building and converting their heating to geothermal heat pumps. We are already seeing substantial European investment in renewables in the US. This is likely to increase as the potential for export improves. The key thing that we need to shake loose of is the yuan's dollar peg. Getting oil sold in Euros might just do that job.

I can kind of see your point that debt as we use it now is tied to growth; we certainly do not have jubilee cycles these days. I listened to two young people join in the sermon on Sunday interpreting the reading about the unjust steward. Neither they nor the priest recalled that a regular cancellation of debt is biblically mandated. Still, they all did well interpreting a difficult text. Now we are going to pay our debt in devalued currency. Is this unjust or ordained?

UAW feels strong enough to strike. They know that there are going to be a lot of cars built with better fuel efficiency and they want to be sure that they are the ones to build them rather than robots. We are not done with economic growth because there is a very big energy conversion to undertake and a huge export market to serve. Because the US is good at process engineering, it will be the US that does much of the industrial work for the energy conversion. The rest of the world is just making sure that it does not cost them too much to buy our products since they will be essential. The losers who speculated in the dollar as a reserve currency will also be winners as they get solar panels, wind turbines and plug in hybrids at a reduced price. Hopefully we will not decide to hold a single currency once we have built up our foriegn reserves. The way I see it, we've baited our hook with the US market in consumer goods to catch the largest possible market in durable goods and having let China run out on our line long enough so that their government's continued control requires what we can provide, it is now time to reel in the profits (Chinese New Year pun intended). The Chinese tradition of not eating all the fish may be as old as the biblical tradition of not allowing debts to build up. They both speak to sustainability in interesting ways.

Chris

The work a society can do is proportional to the energy it has available. It might still be advantageous to spend more as energy gets expensive in order to get work done, but when the energy is not available no amount of money will suffice to get work done. Nor is it simply a matter of applying more labor, because what one man with a backhoe can do in a day, it might take 10 men a week; even those ten men accomplish in a year only a tenth of what the single man with the machine could do. Ten people now must share a gross output only 20% of what it was - or even less if they are working 6 1/2 days a week instead of 4 1/2.

My guess is the present meltdown is already reflecting tight energy and therefore productivity and work. I'm reading Odum's "Prosperous Way Down" right now; he makes much more sophisticated arguments about how energy [not only oil] and economy tie together.

cfm in Gray, ME

Peak oil is something that just geologically happens. It is a mineral minimal bit of brain clattered un-sense borne with good intentions and later becoming an overused worn-out tramp-- that offtrack simple comment can never fully register until the greased ways become rough/gruff and lacking. Money (as we know it) is in bed with the easy greased up petrol dollarium whore. Not a big mystery or concern until the source is stretched in too many geo differing means and starving mouths. Any real stored value becomes mute and is to accept this farce as a tradable medium of ever constant growth built on the nothingness + nothingness = infinitity of more of the same, with ever renewing fossil fueled-up mentalities.

We do not even get the washable stupid truth anymore. Perhaps, this is because we are all too damned brilliantly stupid from taking in their boob toobed lesson sessions to handle it....? In the nearest timetable of funny monetarism (mone here comes the "real" inflated terrorism)(monet of money) as an outlet to those ongoing betterments of bullshit Fedfaux fiat inductions, then, we do not have much of a choice..Or do we?

Ah, the wonders of it all. The great influence of a fiat masters werking and jerking those majic puppet strings in the fogged-up closing daze of empires running low on reality and energy, is a sight to behold.

Oil is not rising nearly as much as our currency is floundering. One is becoming greater in quantified uselessness and the other is becoming greater in quality of usefulness.

God bless the restart of real America.

Did you compile this report before the present economic problems that are affecting the housing and financial markets?

Looking foward to reading Part 3.

Not really. I didn't want to overstate how awful things are.

We live in house of cards land.

I think you're missing one point when claiming, that debt is only a useful instrument if one speculates on rising income.

What about borrowing money for buying a house? I just got married and I want to start a family, which is something I don't wanna do in my parents home. So even if I don't expect my income to rise, if I can expect it to be more or less constant and I can afford the rates to be out of debt in 20 years, I would still buy the house...

But would anyone give you the loan? Without a growing economy, loans become much riskier.

In the old days, people didn't borrow, even for "worthwhile investments." Instead, they saved their money until they could afford it. If you couldn't save enough to get it, you didn't. Even if that meant not marrying.

Leanan,

The problem with individuals saving up money for investments is that is it likely to be very inefficient, particularly so in an environment in which people are struggling to make a living anyways. Saving means forgoing current economic consumption (maybe for a long period of time) in order to make a relatively large purchase later. If the item being purchased is a 40” plasma screen television, then I have no problem with this scenario. On the other hand if the item being purchased is a replacement roof or improved insulation which will save energy, then the personal savings scenario does not seem like the best idea. Making due with tarps while you save up money for a new roof will be more expensive than replacing your roof right now. Living in a poorly insulated house while you save money to purchase insulation will waste energy. A better solution would be for the community to finance worthwhile wealth preserving investments with interest free loans. That is everyone should give up a little consumption in the present in order to make sure that worthwhile investments are made on a timely basis. The reason you should be willing to help your neighbors out in this way is that when your turn comes to make a relatively large wealth preserving investment then your neighbors will help you. The old fashioned version of such community investment was house raisings or barn raisings.

Yes, barn-raisings and such are a possibility. But I suspect it would be more difficult. Barn-raising was most common in 18th and 19th century North America. When resources were not a problem, and constant growth was expected. The growth was fueled by expanding into new territory, rather than oil, but it was still growth.

I think we're going to be in for a rude shock when we find out what a steady-state economy is really like. Where you can't get a job or a house unless someone else loses theirs.

Leanan,

Without a doubt we are in for a shock. But the fact is that our long term destiny (assuming that we are smart enough to survive in the long term) has always been to live in dynamic equilibrium with a finite world and a finite ecosystem of which we are codependent members rather than its god like masters. The process of creating and maintaining the required social and economic institutions should be regarded as a positive challenge rather than as a falling away from the glories of the suburb, the six-lane freeway, and the big-box store. I am imagining something more sophisticated than barn raisings without in any way supposing that the ridiculous excesses of the current economic system can be retained.

I have to say, I have a hard time imagining what it will be like. The two most likely outcomes, IMO, are a return to a sort of feudalism, where birth is pretty much destiny and Malthusian forces keep population in check, or an authoritarian government, like in The Giver, to ensure population is kept in check, resources distributed, and the environment protected.

I'm not too keen on either one, though I'm not in love with the glories of the suburb, either.

Leanan,

I think it is pretty hard to know what outcomes are likely even though the outcomes you mention are certainly possible. You seem to be assuming that voluntary restriction of the human population and democratic cooperative economic systems are impossible so that we will need stern masters (starvation, disease, feudal overlords, dictators, etc) in order to keep our stupid, greedy, expansive impulses in check. I refuse to take this pessimistic view (although I do not assert absolutely that it is incorrect). I see no physical reason why we cannot develop a system of democratic, social investment whose purpose is to preserve wealth for the community rather than to increase the net worth of private investors. If such a system cannot be implemented because we are too stupid and self-centered to carry out such cooperation, then we deserve whatever terrible fate that the end of economic growth is going to bring us.

No, I don't think it's impossible. It's happened, as detailed in Jared Diamond's Collapse. (He writes about societies that have succeeded as well as those that failed.)

However, his work suggests that certain criteria are necessary in order for a society to become sustainable, and the odds are not in our favor.

In particular, he notes that two kinds of societies can succeed: small ones, where everyone knows everyone, and everyone feels a sense of ownership of the environment; and large ones, with strong central control and a hereditary ruler (who has incentive to preserve resources for his heirs). Medium-sized societies cannot make the transition to sustainability. They are too large for everyone to feel ownership of everything, and too small to support strong central control. They invariably collapse into internecine fighting.

Diamond suggests that that is the likely fate of large societies without strong central control as well, and I fear he is right. Democracy - where those in power are only in power temporarily - encourages people to loot the system while they can.

Democracy - where those in power are only in power temporarily - encourages people to loot the system while they can.

The governments of the OECD countries are not democracies. They are governments of, for, and by private finance capital. These governments do not loot because they are temporarily in power; They are in power because they promised their corporate masters that they would be looters. Your claim that democratic cooperative economic systems cannot exist is a claim that democracy itself cannot exist (with the possible exception of village style communism). Of course such cynicism cannot be disproved, and you are right that history is discouraging in its revelation of human beings’ shortsighted selfishness. However, being philosophically a democrat (I do not mean a member of the democratic party) deep in the marrow of my bones, I refuse to admit that history is destiny and will continue to hope that civilization and democracy will some day find a way to coexist.

People behaved unsustainably historically, generally because they did not know the long-term consequences of their actions, but we are better informed now. Since the industrial revolution people have tended to take a short-term and selfish attitude due to economic and social insecurity - the neoconservatives didn't invent globalization, fear-mongering and xenophobia. For example we have enough information on overfishing of world fish stocks to know what policies can improve it, but people pay little attention to such 'altruistic' issues when they are worried about the mortgage.

We need to do two things: replace our growth-dependent debt-based monetary system; and reorient our socioeconomic goals to improving quality of life within limited resources (which includes greater economic equality and local food production). I see two phases of social change happening:

Firstly a period of increasing insecurity, fiscal crises and domestic and international aggression while people demand that the existing big business/government 'fix things'. Meanwhile local groups will be quietly building 'lifeboat' communities with LETS, sustainable businesses and organic farming.

Seondly most people will become disillusioned with TPTB after they fail to deal with major problems (perhaps a peak-oil-induced depression, or life-threatening pollution). At this point the 'alternative' economics will gain mainstream support, social capital will increase, countries will start making the real changes needed, TNCs will be neutered, and international cooperation on climate-change, pollution and resources will improve.

The major unknown is how quickly the second phase will occur, which depends on how long the MSM disinfotainment will keep the sheeple hypnotized. If food production and imports fall too far too quickly, phase two will be replaced by civil war and dictatorship.

This is all with regard to the richer countries. I don't think a major overpopulation/food crisis can be avoided for most of the poorer countries. Cuba was lucky with good soil, permaculture experts and a responsive government; North Korea represents a more likely outcome.

When you say "People behaved unsustainably historically" what exactly do you mean. You go on to talk about the industrial revolution, so is "historical" since the IR?

Civilization is full of examples of peoples living non-sustainably. And in one sense you are absolutely correct if you define historical as recorded history.

On the other hand, many peoples have lived sustainably for long periods of time (some suggest the aborigines of Australia lived essentially the same life for 50,000 years prior to the modern era.

Us moderns have a tendency to want to shorten the length of time that we consider as significant to our lives. Knowledge of ancestors has been reduced to "geneology" on the internet. The seventies was "a long time ago," even for those of us who lived through it. And little prior to WWII (when we fought alongside the germans against the russians ;-)) is considered of any importance.

So when you say "people behaved unsustainably historically," I want to respond with - you're right, and before that we were smarter!

Unsustainable behavoir has been happening from the moment agriculture was invented. Mesopotamia was once rich enough to create the first civilization but is the soil is now largely degraded and salted. I believe Plato commented on the loss of fertile soil in Greece. Libya was once the breadbasket of Rome. The leading civilization slowly moved West from Mesopotamia to the UK as successive fertile lands were degraded and populations declined.

Australia was a largely forested land before the Aboriginies arrived, although the role of man in deforesting it and eliminating large animals is disputed. Agriculture itself can be seen as a response by an overpopulated hunter-gatherer community which degrades the ecosystem.

Some communities have learned to manage the soil so that its long-term fertility is preserved, but generally soils are overexploited until the human population declines from lack of food and the soil has a chance to partially recover its fertility, whereupon the population increases and damages the soil again. This cycle may be 'sustainable' but it's an impoverished state. It's only with the recent development of a scientific understanding of soil and ecosystems generally that we have the potential to improve and maintain our environment.

Looks like we agree, then, that the problem is civilization (as long as you adhere to the connection between large scale agriculture and civilization).

Unfortunately no country, developed or otherwise, has ever agreed to voluntarily limit either its economic activity or population growth. On the contrary the cry is for more growth, on all fronts, by nearly everyone, rich and poor alike. Those who raise the issue of limits and overpopulation are few, and in no position to influence the situation.

This is untrue. Please refer to Jared Diamond, he can provide examples of societies that chose to live within the means of their environment.

This is not to say that our society will ever choose to live within its means.

True, but those societies that did live within the scope of their environment were few and far between and also tended to be very small compared to our global civilization. This smallness made the boundaries of their environment much more immediately obvious as well. And most importantly, the few societies that did live within the physical boundaries of their environment were rare compared to those that managed to destroy themselves either directly or indirectly via ecological destruction.

"The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function." -- Dr. Albert Bartlett

Into the Grey Zone

With the obvious exception of the most populous nation on Earth, China with its one child policy.

An individual's income can grow even without a growing economy. Even now, it's normal for a person's income to start low, grow throughout their life, and then decline when they retire.

When put in that context of personal income growth, lending to a young couple to build their house makes great sense - the lender gets a long-term contract with a borrower whose demographic (young but stable) has a strong tendency towards income growth, and has the loan secured by a tangible and valuable asset (a house).

Indeed, if the economy overall is not growing, such personal income growth may be one of the few opportunities to earn real rates of return on an investment, and hence may be extra attractive for that reason.

That doesn't seem to be true. Here is an article about a book on the history of lending and interest ("usury"), and credit is old. As in, "you can go back to the Mesopotamians who kept records of borrowing and lending on stone tablets" old.

Peasants may or may not have borrowed, but that's because they didn't have much in the way of earning power. Businessmen - the middle class - apparently could and did borrow, even for propositions with a high chance of failure; the article mentions a Genoese trader who had to pay 20% interest rather than the prevailing 8%, due to risk.

So it's not at all clear that long-term economic contraction would cause lending to vanish. What is the evidence saying it will?

But what will you do 3 years down the road if that 200K house is now worth 130K? And it's roof is leaking. And your wife had complications from delivering your second child.

Be extra cautious in today's housing market.

There's always risk. It's unavoidable.

Hypothetically, which would you rather have right now?

$100k in the bank, paying $1500/month in rent.

or

$40k in the bank, and a 30yr fixed loan (240k at say 6.25%) for $1500/month, living in a house that's valued at $300k? With a tax write off to boot?

There's a ton of talk here about deflation. And don't get me wrong, it's a worry. But M3 is growing at 12% a year. The fed just gave away billions in loans with nothing but crappy mortgage bonds as collateral. England guaranteed all deposits at Northern Rock. Inflation is high. The government has trillions in unfunded liabilities...

INFLATION IS THE SILENT TAX.

If you want to bet against inflation, be my guest, but I've always found it hard to make money betting against the long term trend.

I'm not saying buy something you can't afford. I'm not saying buy 6 houses. And I'm sure as hell not advocating tapping into your home equity to buy a boat or SUV. But a properly financed, 30 yr fixed mortgage (or even better - a 15 yr mortgage) makes a lot of sense to me.

But what do I know.

G

This is a dilemma that I think about a lot. Betting for inflation generally is harmful for society (such bets typically increase consumption), but betting against it is asking to lose ones shirt.

You are assuming that the income source will always be there and that assets and commodities inflate proportionally. It also fails to consider the rising cost of maintaining the value of the property.

The odds of all this going ones way are much less then even and most likely vary with location.

If it were my deal I would like to have the 100K in gold outside of the US and would reduce my rent payments drastically.

The problem with property, especially near major cities, is that the value can drastically deflate due to above ground issues (in TOD speak), while commodity prices increase.

If you lose your job, then you have to get another one. And if you can't get another one - you might lose the house. But that's always been a risk. You can minimize that risk by not buying the "max" that you can afford, and by having 6+ months of reserves in the bank.

In my mind - it comes down to weather or not you believe the current "system" is going to continue on fairly long term (20+ years) or if you think a big disruption is going to happen sooner, say 5 or 10 years.

There always is risk but the risk is not always the same.

Right now the risk is very high and has to be priced into it.

If you feel that you can, or more accurately "will want to", hang on to the property long term and think it will increase in value then go for it.

My experience has been that even in good times the real estate I owned remained desirable for only so long even in an appreciating market. The only exception may be very high end property.

Inflation is the silent tax, agreed.

But, most today refer to the "bubble" As in exceedingly inflated or about to burst.

The problem is a couple years down the road. And for whatever reason, you have to sell. An asset that has declined in value and eaten up your hard earned down. Markets are pretty unforgiving, you may sweet talk an agent to listing at what you paid, but it'll sit. The fact that your income has remained static only compounds the problem. You borrow more.

So it is a gamble. I think the majority of the folks today can't believe real estate prices will fall. Appreciation is the only game they've known, and they still play it.

The flip side says keep your freedom, and your ability to move from one low priced rental or better job to another. Invest the difference in assets which are known to be appreciating, or expected to. Avoid those who seem likely to fall. Should housing stabilize, and your employment picture remains bright, then buy. Also, by then, your family's needs and your picture of the ideal home may be different.

"Tax writeoffs" work only for those with sufficient income. For most, it's not worth itemizing.

Everything is a gamble!

Housing, Oil, Gold, and stocks, are all "gambles." Obviously, the name of the game is to pick the asset classes you think will do best.

I don't see housing that way at all. It's a fixed cost. You have to live somewhere. Pay the mortgage off quicker if you can. If you can pay cash for it - so much the better!

I guess I just see "cash" as a much riskier investment long term then I do a piece of real estate.

G

I'd take the rent - easier to up stakes and change cities if the climate gets too problematic, move closer to jobs or transit, etc.

Thanks for tackling this subject. I've been hesitant to ask the actuaries I know about peak oil. The couple I mentioned it to weren't keen on considering it, and since I left the actuarial track some years ago I'm not too close with them anymore.

I just wanted to let you know that an actuarial approach is appreciated.

Keep up the good work, it's good to have you contributing.

Question: Do you discuss Peak Oil with other FSA/ASAs (actuarial designations)? What type of response do you generally get?

My experience is that people buy into infinite growth and they are wearing blinders to any alternative (short conversation, I don't even bother anymore).

With actuaries, as with others, you get a variety of responses. I have found quite a number who are interested in the subject. I first heard about peak oil in an actuarial publication, several years ago.

"Shunyata", author of Monetary Policy and Weaseling Out of Debt, is an actuary, among other things. His view is similar to mine, or bleaker.

Poster 710 has passed several actuarial exams. There are several good comments by 710 on the Part 1 thread, including this one.

I wrote an article for the May 2007 issues of Contingencies magazine (sent to all actuaries) titled Our Finite World: Implications for Actuaries. I got a lot of favorable e-mails and phone calls about it (from 0.1% of the readers).

I was recently asked to write a similar article for the "Actuary of the Future" publication of the Society of Actuaries. I believe this will be published shortly.

So there are at least a few actuaries who are interested in the subject. I think a lot of them are scared by the subject, or else have never stopped to think about the problem.

Great article. With so much raw information and opinion available its a huge relief to see someone investing from themselves to benefit everyone else with sound reasoning and construction. Tying the oil price risk and the credit market risk to the full economy is a meritorious effort and worthwhile read for everyone. Gail has done an even better job than last week's piece making it understandable by everyone. We've reviewed it and are encouraging our readers to share Gail's work at http://newenergyandfuel.com/ with others.

Thanks! Glad you like it!

I've got a question about fundamental "philosophical" issues rather than the technical aspect of money/debt/financial growth as underpinning of the modern economy.

If things do change radically, as it seems they must, and the current economic arrangement of an ever-expanding economy backing up a debt-based monetary system changes to something else, does it follow that the practice of lending at interest will be abandoned of necessity? I guess my question suggests an answer (that is 'no'), but I would like to get some feedback on a few issues.

First, and just briefly, I believe there is historical precedent for money lending at interest in the absense of hydrocarbon energy supply. Maybe someone with more knowledge can consider if that is a system that might be returned to, or readapted to the midterm(?) future.

The second point is more general. I've posed this question on reddit before with only tepid response. Suppose peak oil production causes disruption in the energy system -- this seems likely to me I don't mean to question this assumption. Is the following a reasonable post-peak-oil scenario? Development, production, lending, population etc. simply scale down in a smooth slope without any more cataclysm than we're seeing now. I have in mind a situation in which the western lifestyle becomes much more like subsistence living, but the change is gradual and relatively peaceful? I don't think this scenario is particularly likely, but I'm curious to see an argument to the effect that the post-peak-oil situation will be catastrophic.

On a related note, if such a gradual scale-down were possible, could a finance system based on money lending at interest be possible for "value-added" production. I have in mind a situation in which I borrow money from a bank to build a brewery or bakery, and I do so, and the value I'm able to add to things like wheat, malt, barley and hops allows me to make a profit and repay my debt. It doesn't seem that this sort of arrangement necessarily involves massive hydro-carbon energy inputs and seems the sort of thing that could work in a money based economy.

In the ancient world, people did borrow money...but only if they were desperate. That's why there were such strong prohibitions on "usury" - charging interest on a loan. Paying back a loan was difficult enough without adding interest.

I think it's more likely that you be required to save up the money to start your venture. Perhaps with help from your extended family.

Another thing they used to do, and still do in many countries, is a kind of lottery. It's usually within a family or other small group. Everyone puts a certain amount of money in the pot, and lots are drawn to see who wins it. The winner might use the money to buy a house, or start a business.

Leanan

A number of Vietnamese and Chinese immigrants in Houston in the 1970's and 1980's used that system, but they were'nt necesarily blood related. Its been superceded since their community started banks. A lot of Moslems in the area have similar arrangements, because the religion of Islam prohibits interest. These seem to be more family related, though.

Bob Ebersole

Schmendrick,

I think post peak oil you can get short term collateralized loans, such as for inventories. Longer term, there tend to be too many defaults, and the interest rates (with the charge for defaults) becomes exorbitant. By the time you pay the high interest rate, it becomes very difficult to make a profit with your brewery or bakery. There is also a possiblity that you will find no one to make the loan.

Regarding whether you can have a gradual scale down or not, I look at that in Part 3. My conclusion is that you cannot. There are too many discontinuities that take place - both on the side of oil exporters and on the side of oil importers.

Your scenario is you wishing upon a star. What you describe happening would occur only if certain conditions are met:

1. Economic contraction occurs at exactly the same rate as fossil fuel decline rates.

2. Population contraction occurs at exactly the same rate as fossil fuel decline rates.

3. Fossil fuels are not substituted out at all.

These occurring together are extremely unlikely.

Instead, the question needs to focus on alternatives and substitution rate versus decline rate. If the substitution of non-fossil fuels can occur as fast or faster than fossil fuels decline, then civilization stays intact (although it may also reorganize itself along new energy lines). If substitution rate is less than fossil fuel decline rate, then we have catastrophe in some form awaiting us.

This is why so many in the peak oil camp are not just worried about total URR (ultimately recoverable resources) but also about the extraction rate of those resources. It doesn't matter if we have 10 TB of liquid fossil fuels if we can only extract a maximum of 5 mbpd due to various limits on the system (hypothetical numbers there simply to drive home a point). Flow rate is very important as it directly correlates to how much fossil fuel energy we can use per unit of time.