The Economics of Oil, Part II: Peak Oil and the Energy Supply Curve

Posted by Prof. Goose on September 13, 2007 - 10:00am

This is the second (the first can be found here) in a series of guest posts by Robert Smithson, a portfolio manager at a London based investment fund.

Introduction

The world’s oil supplies are not unlimited. Unless the abiogenic theory of oil is correct, then reserves will one-day dwindle, and production will decline. New barrels cannot be “magic-ed” by some trick of economics. Extraction of any fossil fuel extraction is limited. Peak oil is inevitable. Of course, there is debate about when production hits its highs; it may have already happened, perhaps it will come in the next few years, and just possibly, it will be in 2020 or later. But make no mistake about it, we are not endowed with infinite amounts of the stuff.

Sceptics rightly point out that this bell has been rung before. In the mid 1980s, world oil reserves were forecast to last about 20 years; and yet here we are in 2007, with near record production levels. Historically, we have always found new sources of oil – in Alaska, in the North Sea, in the Gulf of Mexico, and off the coast of Africa – to satisfy our addiction. There are prospects in the future too: there may well be (very substantial) new discoveries in the Middle East, ultra-deepwater drilling holds promise, as does the development of new areas such as the South Atlantic, and increased enhanced oil recovery will certainly play a role. This misses the point: finding new oil reserves may push out peak production, but it does not invalidate the concept. Our planet does not contain an unlimited amount of oil.

Many – particularly on this site - argue that economics has little that is intelligent to say about peak oil. Yet the very definition of economics is the study of scarcity, and in particular, the study of the efficient allocation of scarce resources. What more relevant subject could there be for studying the effects of peak oil?

Peak Oil and Micro-economics

Over the past fifty years, mankind has prospected for and found enormous quantities of oil. These discoveries and their development have relentlessly pushed the oil supply curve to the right. That is, at any given price point, more oil will be supplied. Simultaneously, we have seen economic growth; people have become richer, and with more money comes greater levels of demand for oil (petrol for their new cars, kerosene to fly them to their second homes in Florida or the South of France). The demand curve has also been pushed to the right. The result is that – until the last few years – we have seen constantly rising oil supply and demand, while pricing has remained broadly stable in real-terms.

This process appears to have broken down in the last few years. Oil prices have risen, while the quantity supplied has not. In other words, the demand curve has moved to the right, while the supply curve has stayed broadly in the same place. Economic theory suggests this should lead to greater investment in prospecting and development. Yet persistently high oil prices – by historical standards – have not led to any increase in capacity.

There are a number of reasons why this might be: suppliers might be waiting for evidence that the demand curve has moved sustainably to the right (those who invested in oil shale projects in the 1970s did poorly), or projects might simply take long-periods before new oil comes to market (the Sakhalin II project was signed in 1996 for instance). Alternatively, we may be at or approaching a peak in global oil production. This may be Hubbert’s Peak.

Are We There Yet?

Oil watchers tend to discount the evidence of the market, often accusing it of being “blind”. But they would do well to keep an eye on one of the more interesting indicators, the oil forward curve. This measures what people will pay for a barrel of oil to be delivered at various points in the future. These forwards are the only way to bet on long-term movements in the price oil. The two charts below show forward pricing for oil (NYMEX) futures, and are taken from Bloomberg:

In August 2002, the markets forecast oil prices would fall, and keep on falling. You could buy oil for August 2007 delivery for under $23 a barrel. That would have been quite a trade. The current chart is more interesting; it sees oil prices trough at the end of 2010 and then begin to rise. For the first time in all my experience in looking at oil forward curves, there is a long-term upward bias. As recently as February of this year, the long-term curve pointed downward.

These charts do not, of course, show that peak oil has been reached. (The market was woefully wrong in August 2002, so its predicative power should not be over-stated.) What they do show is that the market does not expect new sources of oil – be they from oil sands, or from ultra-deepwater – to move the supply curve sufficiently to the right to mitigate rising demand from China and India. In other words, the market is forecasting a period when oil becomes less abundant.

What Does it Mean?

Let us be bold: let us assume that the market is not only right that oil will become less abundant, but that overall supplies will start falling. (This is not an unreasonable assumption: after all, production in Mexico, in the US and in North Sea is declining.) What does this mean?

Well, firstly, it does not mean oil stops being pumped! On the contrary, it merely means that the supply curve stops moving to the right. For any given price there will be less oil supplied. In the short-term, demand curves will not change: the pressures from economic growth in India, China and the like will not have abated. In other words, prices will rise.

But they will not spike due to some sudden “realization”, because the price dynamics have not fundamentally changed. Realization means nothing to the spot price of oil. That price will continue be the level which causes (slightly diminished) supply and demand to meet. (The argument that speculators would or could use large underground “reservoirs” to store oil is spurious: the cost of doing so, once one includes the capital charge for owning the oil, would be enormously prohibitive. If you wanted to bet on rising longer-term oil prices, you’d simply buy the 2012 futures.)

The other thing worth noting is that the decline in total oil volumes produced suggested by Peak Oil is relatively modest, at least initially. The chart reproduced below is from Hubbert’s 1956 Paper “Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels”, and suggests that production will only have fallen 20-25% by 2030 (although it does fall off more steeply after that).

As we described in the reaction of the world to the 1970s oil shocks, increased awareness of higher long-term oil prices, will cause the demand curve will change. Before going into the details, let us not forget that between 1973 and 1985 (just 12 years), world per capita oil consumption fell from 5.45 to 4.40 – a 19% reduction, a period during which world GDP still increased at a 2%+ rate.

The Price Elasticity of Oil

There is still a great deal of skepticism about whether demand for oil is price elastic. Much is written about “Minimum Operating Levels” of oil, below which a modern economy simply cannot function; and while there may be a minimum level of oil required – although I suspect there is actually more of a minimum level of energy – it is well below current levels, particularly for developed economies like the US. This can be demonstrated by looking at the “oil intensity” of various developed nations.

According to the CIA World Factbook, the United States currently uses 68.8 barrels of oil a day per 1,000 people. This compares to 43.8 in Japan, 32.2 in Germany, and 30.1 in the UK. While some of this might be explained by the greater distances people have to traverse in the US, it can hardly be the only reason - after all, there are large distances to cover across Europe. The point of this data is that the US and Canada are anomalies: their economies use more oil per person, and more per unit of GDP than comparable countries. There is ample opportunity to become more energy efficient without causing significant economic damage.

The other interesting piece of the puzzle is the driver of oil usage. Looking at countries with similar GDPs and population densities, but different oil per capita oil consumption, it is clear that gasoline pump prices are the largest determinant of oil usage. In other words, where the price of oil (gasoline) is high, consumers use less. And this difference in consumption (which can be in the order of 40-50%) has little to no effect on GDP. The following tables (based on 2004 data) illustrate this:

Developed Countries

Price per Litre Oil Consumption per Person

UK 156 30.1

Germany 146 32.2

Spain 121 38.9

Ireland 129 44.4

Greece 114 40.7

US 49 68.8

Developing Countries

Morocco 110 5.0

Tunisia 68 8.7

Russia 55 17.7

Saudi Arabia 24 66.8

Kuwait 21 133.7

(There are some countries – although surprisingly few - which clearly do not fall into this pattern: The Netherlands has some of the highest petrol prices in the world, but also has high per-capita oil “consumption”. This is due to the Port of Rotterdam, and its associated petrochemical industries.)

For those who think these numbers are somehow cherry-picked, or contrived, the chart below tells the tale in a different way. On the x-axis is the GDP at purchasing-power parity created by each barrel of oil, and on the y-axis is retail price of gasoline (US$, March 2005). Countries where gasoline is more expensive, use it more efficiently. Or, to put it another way, consumption reduces surprisingly efficiently in response to higher prices.

The evidence is clear: people respond to higher prices of petroleum products with reduced consumption, and this reduction does not necessarily result in economic catastrophe. Consumers are rational; their consumption of oil depends on its price. And oil products are surprisingly price elastic – at least over long-periods. Reducing world oil consumption by 25% in the next 25 years, with the price mechanism as the driver, can and will happen. It may not be pleasant, and it may well result in lower economic growth and higher unemployment, but it will not be a disaster.

The Energy Supply Curve

Do we really demand oil? Or do we really demand usable energy? Oil is not the only source of energy in the world. There are alternatives. Forty years ago, oil was commonly used to generate electricity. Today, outside oil exporting countries and the occasional peaking power plant, it is virtually unknown. It is just not economically efficient to generate electricity from oil. Electricity generators are rational consumers: when the price of one input got too high, they switched to another. Of course, this happened over a long-time, but the impact was relatively modest.

When we think of oil as something unique and irreplaceable, we make a great mistake. Oil is just a store of calories, in the form of long chain hydrocarbons. When it is burnt, it releases those calories as heat, which can be harnessed to turn a turbine for electricity, move a car, or fly a plane. But it is by no means the only store of calories. Even just taking other hydrocarbons (so-called fossil fuels), there are supplies of coal, tar, oil sands, methane, gas hydrates, and other gases. The total calorific value of these supplies outweighs that held in traditional crude oil. In addition, there are alternative energy technologies: wind, biomass, geothermal, nuclear, solar. Mankind can extract calories from each of these, and in the case of the latter two, there is the possibility of almost limitless supplies of energy.

We think of the oil market as monolithic, as standing on its own. It's not. Oil is just an incredibly convenient source of calorific energy. It has an infrastructure already in place, and a reasonably efficient mechanism (the internal combustion engine) for translating its energy into motion. If the oil price exceeds the price of alternatives (and it already has in baseload electricity generation), then alternatives will substitute it. The long-term price of oil is determined by the price of alternative energy supplies.

That said, this convenience should not be underestimated. In terms of energy density, there is nothing – except nuclear power - to match oil products. Gasoline has 47m joules of energy per kilogram, and 35m per litre. Even the best batteries are an order of magnitude worse. (Interestingly, liquid hydrogen has fairly good characteristics from an energy density perspective, and can be generated – albeit not particularly efficiently – from electricity. This is why there is so much focus on hydrogen power – whether fuel cells or a straight hydrogen burning engine. There is, of course, no infrastructure in place for the distribution of hydrogen.)

Living in an Oil Constrained World

According to forecasts from the Energy Information Administration, world consumption of oil will rise from a little over 150 quadrillion BTUs in 2003 to almost 250 quadrillion in 2030. While anything is possible, this would require extraordinary discoveries; indeed even assuming continued improvements in recovery rates, the world would need to discover the equivalent of all the oil extracted ever in the next 20 years. Good luck.

That won’t happen. We’re going to live in a more oil constrained world. But we’re also going to discover that this isn’t the end of the world. These articles have focused on demand destruction caused by higher prices; perhaps it is more helpful to think in terms of more efficient use of energy. People will drive less. When they do drive, they will use more fuel efficient cars. 100 miles per gallon is not unachievable. More energy will be consumed from the grid (where nuclear will make up an ever greater share of generation). When we go off-grid, we’ll use batteries more, and fuel oil less.

Public transport – particularly buses and trains - will look better value, while airlines will look for more fuel efficient ways of flying. (Ultra-high bypass engines – aka Propfans – which have 20-30% fuel savings over traditional jet engines may enter widespread use as fuel efficiency becomes more important than speed.) Even so, the price of air travel, which has been on a downward curve for the last quarter century, looks set to rise. People will respond by traveling less.

Consumers will react in predictable ways. If getting to out of town shopping malls is difficult, they will instead head into towns for their consumer goods. Likewise, businesses in cities will have an advantage (it is easy to commute into cities by public transport). Indeed, the demise of the high street is mostly the consequence of cheap personal transportation; i.e. the car. So Cities will look more like they did 70 years ago, with central areas preferred over suburbs.

We will become more reliant on telecommunications networks, and the economy will become more service focused. It is fortuitous that video conferencing and the Internet are maturing and improving at the same time our oil supplies are beginning to dwindle. We will need to spend on grid infrastructure: on HVDC lines to reduce transmission losses. There will be investment in nuclear power stations, with commercial fast breeder reactors, and a move from Uranium and towards Thorium. Biofuels, from sugarcane, will become more prevalent. There may be commercial algae farms in the next decade.

Oil will not stop flowing just because peak oil has been reached. We are fortunate that the downward curve of production will probably be as gentle as the upward one. Even in a hundred years time there will probably be commercial production; it will just be an irrelevancy as a percentage of global energy usage. We are given an awful lot of time to adapt to an oil constrained world.

More important that what will happen when we pass peak oil is what will not happen: there will be no queues at the gas station (why should they: we have rationing by price), the electrical and water networks will not cease to function (they were there before we got our present oil dependence), and some people will continue to buy gas guzzling SUVs and Ferarris (there will just be very few of them, and they’ll pay extraordinary sums for the privilege). The government will not collapse. Democracy will not come to an end. Economic growth will not end. Our lives will not look so very different to how they do: or at least they’ll look no odder than our lives would to those who grew up two generations ago – in an age before the automobile was ubiquitous.

Economics does not provide an answer to declining oil supplies. Its models try and explain – however imperfectly – how people will react to a scarce commodity becoming scarcer. The price mechanism is a powerful thing: it forces people to prioritize and choose, and it performs a rationing system. This is not to say a transition away from oil as a primary energy source will be painless. But we must avoid the trap of thinking there are no alternatives, and we must avoid the conceit of thinking these alternatives are costless or easy.

Nice commentary.

The real danger comes from those who would try to ration by some means other than the price mechanism ... the "entitlement society" has caused a whole generation of people to think that they are entitled to things they can't pay for.

I like much of this. We can adapt to nearly everything. It is not price but price spikes, economic heart attacks, that will get us into trouble.

We can even contain most of those if we act in advance.

Acting in advance will also mitigate increased political risks during periods of flux. What will Mexico be like when they lose their oil revenues?

bill.james@jpods.com

It costs less to move less

We can only adapt to things to which our physical existence gives possibilities to. No amount of economic modeling can know this. Only physics can and even that very roughly/approximately.

As for Mexico, oil exports are c. 20% of their export revenue. As such, the fall in exports is probably not critical on its own, but there are another factors:

RISK = Lost oil exports + Increased oil imports * increasing oil price + supply risk (i.e. delivery disruptions in imports)

This combination may be harder to stomach for Mexico at least temporally as it is not just a mere price hike.

Time will tell though. I hope that Mexico will weather this well, but I'm not counting on it.

This is, I think, the exact problem with the analysis above. It is based on a model which does, to a great degree, reflect the economic processes involved.

HOWEVER - after having said this...

Your first assumption is that the oil market is a "free" market. This changed at the latest in the 1970s after production in the US peaked. National oil companies now account for 80% of production!!!

Are they going to react free-market rationally to make sure that production drops are gradual? OPEC did the exact oposite at the end of the 1970s, if I may just offer one small case in point.

I missed the part of the essay which acounts for W*A*R, natural catastrophy and other "minor" disruptions which can and will change the world over night.

And who is going to garantee me that I'll get my petrol when I need it??

I have no problem with steadily rising prices when I can the act accordingly - and *rationally* by conservation etc.. What will more than likely happen is that I wake up in the morning and find out that the local gas station won't be able to fill my tank on that day - just because some tanker riffed somewhere between here and Nigeria, ie a very tight supply chain snaps. What to do? Jump into the non-existent public transport? Buy a house in town that I can't afford and won't be finanzed for anyway?

Post Peak will hurt, despite all signs at the moment of a relatively funtioning transition.

Next objection:

Living in Germany, I would agree from experience on the fact that higher prices influence consumption. This ASSUMES however, that these prices happen gradually. Petrol was extremely expensive here 16 years ago when I came - and since then it has gotten much more expensive. No problem, we all had time to adjust. What would we do if there were a sudden price spike - say doubling or trippling? Of course - change my lifestyle!! It's just too bad that this doesn't happen over night. Or how fast can you move out of the suburbs when everyone else wants to move out too? House, kids, mortgage to the hilt, job too far away, public transport (which I already use, by the way) which is already a pain in the gazoo.

Cheers from Munich,

Dom

----------------------

Just remember the Golden Years, all you at the top!

http://science.reddit.com/info/2p2rc/comments

if you are so inclined...

If price rationing would work without any big problems, then what`s the problem with Peak Oil. It would merely mean ever higher price of gasoline, and a lower economic growth rate.

And then the price should force the society to adapt to other solutions with a lower energy use.

I hope he is right there. And perhaps he is. Well i hope he is.

EDIT: If we would solve this with price rationing, then USA with very small gasoline taxes, should have big problems compared with the Europeans who could easily lower already high taxes to mitigate the impact on its citicens.

So now i understand, why USA has chosen the military option.

I agree that price rationing alone may not solve the issue and to think like that would be utterly foolish (reality doesn't follow an economic model, esp. such a broken one).

As for US/gasoline tax/war option, how about UK? They have high gasoline tax as the rest of the EU, but they are still with US in the oil wars.... err... I mean the great generational just war against terrorism (sic)

Well, i don´t know why UK is in the war. But i know that Sweden has a military force in northern Afghanistan supposedly for idealistic reasons helping the people of Afghanistan, when they and some other countrys in reality are lured by the US to be a part of the oil war.

EDIT: I hope Sweden as payment will get a share of the oil US is going to steal from the region.

I've pointed it out many times before, but price, availability , and in particular supply models post-peak are in a different world to those pre-peak. Attempting to take pre-peak 'elasticity' curves and trying to predict what will happen post-peak is a mugs game.

They are very much different worlds.

Sure, the world could make sane and sensible decisions as to how to reduce demand to match supply. World history is the history of a world not making sane and sensible decisions. Economics is a best a set of temporary, localised, rules of thumb that don't survive upheaval.

Spot on. No matter how sensible economic theory will work in a post-peak world and how other forms of energy will be brought to bear, the underlying presumption of this exercise is that this problem is occuring in its own perfect isolation!

This is a tragically false assumption, albeit not an unsurprising one. Any reasonable assessment of the facts now coming to light about our climate change problem and its unforeseen effect upon the Arctic region -- whether it be the preciptious decline in polar sea ice, Greenland glacial melting, or tundra thawing -- refutes this pure economic stance.

Economists can and do wager what the economic cost of this change will be, but as yet we've done little to alter any of it, be it peak oil, climate change, or most any other ecologic degradation from growing worse with our economic practices that do not accurately reflect the real costs involved.

IMHO, abstract economic theory one thing (of which our GNP, the DJI, and the prices of anything reflects), and messy earthly and human reality is another. Neither are in accord with one another but one will definitely soon strangle the life out of the other.

In either case we are losing badly.

"Supply and Demand in the Irish Potato Famine"

During the Irish Potato famine, at least a million starved to death and at least as many emigrated --as we all know -- while the English landlords continued to export food from Ireland to Britain and the Continent.

I would like to see the supply demand curve for this.

It would seem (from the viewpoint of the economist) that demand for food fell during the famine. Since peasants had no money, they could exert no demand (demonstrations, rioting, theft etc. are, of course, not considered modes of expressing demand).

It is an interesting point of view: I can starve to death, needing and desiring food, but without "demanding" it. I can only "demand" it if I present whatever amount of money is required to buy it.

In the Energy Descent to come, presumably things will be similar. Demand (as defined above) will fall, but it won't be because desire or need has lessened in any way.

Excellent point. I agree completely.

The green, blue, white with red outline bell curve appears to be skewed to the right. Why?

Are septuagenarian differentiations of the normal density correct or not?

Legal cheers

Put me in both the disagree and agree columns.

In the disagree column, the problem with supply is threefold: exports; exports and exports. From the point of view importing countries, the aggregate world oil supply is largely irrelevant. Importers are primarily focused on two things: domestic production and net world export capacity.

Our mathematical model (Export Land Model, or ELM), real life case histories and our quantitative forecasts suggest that net export declines accelerate with time, e.g., the UK went from peak net exports in 1999 to net importer status in 2006, from an initial exponential decline rate of 38% per year to a final exponential decline rate of 178% per year. I have compared a net export crash to an airplane doing a terrifying near vertical dive into the ground.

Having said that, regarding the "agree" column, Alan Drake has documented how the US and Switzerland arranged for the transport of people and goods with minimal oil input--via electrification of transportation.

WT: Basically I agree with your ELM, but IMO the UK experience obviously cannot be extrapolated to exporters like KSA. KSA's reliance upon the export of crude oil is too great for a similar decline to occur. The UK, economically speaking,was never reliant upon the exportation of oil, unlike KSA.

The UK and Indonesia case histories are interesting. It would be hard to find two more different net exporters.

UK: high per capita income; high energy taxes; minimal rate of increase in consumption. Result: Peak exports to net importer status in seven years.

Indonesia: low per capita income; subsidized energy prices; rapid increase in consumption (4.4% per year from 1996 to 2005). Result: (1996) Peak exports to net importer status in eight years.

ELM: Peak exports to net importer status in nine years.

WT: You could be right, but for KSA to go this route would be economic suicide. I still think any countries that are, economically speaking, based around nothing but the export of oil or oil products should be slotted in a separate category. KSA is obviously the first one that comes to mind-possibly you could refine your model to attempt to account for this (just a suggestion).

The 2005 to 2006 numbers for KSA are as follows (exponential increase/decrease):

Production: -3.7%/year

Consumption: +5.7%/year

Net Exports: -5.5%/year

Extrapolating from year to date numbers, my guesstimate for 2007 is as follows (I am adding in some increased liquids consumption, because of their natural gas shortfall):

Production: -5.6%

Consumption: +10%

Net Exports: -9.5%

"WT: You could be right, but for KSA to go this route would be economic suicide."

Nope. As long as prices rise faster than exports fall, they will keep making money. And because of the low elasticity of oil, that is almost certain. Oil prices have doubled, but they are only down about 8-10% on supply. That does not look like suicide to me.

Plus the US chemical and fertilizer industry is closing and heading to the Middle East, so they will be able to diversify (didn't they just purchase Dow Chemical?).

Jon Freise

Analyze Not Fantasize -D. Meadows

G: I was referring to WT's example of two exporters actually going to net importer status. Hard to see how KSA would have a functioning economy as a net importer of oil and refined products.

I thought it was interesting that Indonesia's consumption kept increasing until they were a net importer.

What is your estimate for Mexico?

bill.james@jpods.com

It costs less to move less

Mexico is an odd case. Their consumption was increasing, up until 2006, when it actually dropped, probably because of the sharp drop in transfer payments home from workers in the US--presumably because of the decline in housing construction.

Their 2004 to 2005 net export decline rate was -9.7%. If their consumption from 2005 to 2006 had increased at the same rate as 2004 to 2005, their net export decline rate from 2005 to 2006 would have been -12.0%. However, because of the decline in consumption, their net export decline rate was only -1.7% from 2005 to 2006.

In any case, they were the only top 10 net exporter to show a decline in consumption from 2005 to 2006.

The question on the production side is how long they can partially offset the Cantarell decline/crash. I'm surprised that production is not falling faster.

Do you have numbers on what part of the governments ability to act depends on oil?

Political instability seems likely as revenues drop.

Except for the positive feedback loop--cash flow increases (for a while), even as exports decline, because of rising oil prices.

Pemex accounts for a huge percentage of government revenue. I don't have the exact number though.

I did not find specific numbers but it looks like political instability will be a significant risk post peak.

Thanks for your insights.

http://www.brookings.edu/views/op-ed/20070905martinezdiaz.htm

Finally—and this Mr. Calderon recognized less explicitly—the Mexican economy remains perilously dependent on the country's northern neighbor. Ninety percent of Mexico's exports and 70 percent of its imports go to and come from the United States, while some 65 percent of Mexico's foreign direct investment comes from US investors. Nearly a third of Mexico's commercial bank assets are owned by US financial institutions. And crucially, over $20 billion in remittances from Mexicans working the United States flow into the economy every year, providing the country with a major source of foreign exchange and improving the lives of thousands in some of the country's most depressed areas.

According to Wiki the Mexican fed takes 60% of Pemex's Gross, or about $US 46 billion / yr. this in turn is claimed to be 1/3 of the Mex. Fed. Budget

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pemex

"Taxes on the state oil monopoly Petroleos Mexicanos SA, which faces declining output, now account for about 40 of collections"

The KSA has very large investments in refining in the US economy. When Texaco lost the lawsuit to Pennzoil over the Getty takeover, they sold 1/2 of their refining in the US to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. If you'll recal at that time they were worried about maitaining market share. That's the real reason they flooded the world with crude in the middle 1980's, not some nonsense about ccoperating with Reagan to destroy the Soviet Union.

They've also bought other US assets for years, including treasury notes. The Saudi's have no desire to knock down the house of cards, but members of the extended family certainly do. And I'm sure the US refining industry isn't their only foreign invetsmenst, they apparently have large investments in the European Union too Bob Ebersole

Westexes, I thought you and Khebab where working on a story that gave a more detailed ELM prediction for the decade ahead. I havn't seen anything yet, is it still in development?

Regards, Nick.

We will do a preview in late September, with the final report delivered at ASPO-USA. It will not be a pretty picture.

As an finance type, I enjoy reading a post that doesn't completely discount the impact the invisible hand will have on peak oil. However the post ignores ELM as westexas points out. You also ignore the ecomomic and political fallout that demand destruction will have in less developed nations. Sure I can walk to the store and save the fuel but what of the african village that can't irrigate their crops for lack of any useable energy source?

Is there any precendent for ELM or for demand destruction in marginal economies that we could look at to see how it will impact the global economy. Is an orderdly energy descent possible globally or just in the developed nations?

Only with nations that have lots and lots and lots of social capital

Robert,

Thank-you for this fair and very well researched post. I have a couple of points:

- Oil futures curves imply an expected discount rate in addition to the commodity price. The August 2002 oil futures curve did not necessarily mean that investors expected " oil prices would fall, and keep on falling". It only meant that they did not expect prices to rise as fast as other investments available at that time, like flipping real estate. They were right, and that's why they make the big bucks. Maybe they no longer see easier money ahead?

- The best batteries are almost two orders of magnitude less energy-dense than oil, and when the weight of the containment system, be it cryo-tank, pressure tank, hydride medium, or whatever, is taken into account, hydrogen is about 1/5 as energy dense as oil. Fine for land transport, but a Boeing 787 at take-off is 40% kerosene by weight, so for aviation there is *no* substitute. The last of the oil and coal will used almost exclusively for aerospace, and after that it will be synthetic kerosene.

Half: No. Anyone, in 2002 that was confident of an oil price of $80 in 2007 would jumped all over it. They do not make the big bucks because they are usually right, contrary to popular opinion, and they did not miss this one because they were distracted by property flipping.

Some property values have doubled in that time, and did so smoothly. Oil has been volatile (and is currently off almost a dollar from yesterdays record) so harder to read. No-one could have been completely confident in $80 and thats the point. Plug that volatility into Black-Scholes and I'm not sure even in hindsight that a smart investor would have taken the bet.

Some reference on energy density

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_density

For planes, we still would have biofuels or fuel produced using other power sources like nuclear power.

Plus for planes and all vehicles we can reduce the weight and redesign them.

An all solar plane flew for 54 hours recently (very low energy density). It would be a passenger plane replacement but it shows that intermediate versions could be made.

Also, further in the future there is beamed power.

http://advancednano.blogspot.com/2007/05/lasers-and-magnetic-launch-for-...

Basic trials have been performed that shows that the systems can work. The systems can use laser arrays (allows for the many smaller 100kw lasers that can be built to take the place of the GW lasers that we cannot) and mirrors to reflect the lasers (boosting effiency by 1000 to 100,000 times)

=========

http://advancednano.blogspot.com

if the beams were properly formed in the first place, no mirrors are needed, mirrors always cause losses. The beam will lose coherence due to atmospheric dust and some refraction, but mirrors are usually a loss once the beam is on the way to the target.

the solar plane was unmanned irrc. adding passengers would make for some tough trips because these planes are really only good at moving near the equator, or at a fixed latitude. moving from a given latitude means the solar panels need to be reoriented(and this thing is suppose to fly) which affects the aerodynamics in a profoundly negative way (in addition to adding a host of complexity.

There are two kinds of laser propulsion.

without mirrors you just are providing energy for a block of propellant.

The other is pure photonic propulsion.

http://advancednano.blogspot.com/2007/02/photonic-laser-propulsion.html

Photonic Laser Propulsion has had a proof of concept demo it generated 35 micronewtons of thrust using mirrors that generated 3000 times amplification. You need the mirrors and amplification because photons only impart so much force at each reflection.

The 10 watt laser was based on 100 watts for the total satellite power budget. Thus the best mirrors (20,000 times amplification) would deliver 1.3 milliNewtons.

If they can use the MIT dielectric mirrors those are supposed to reflect 99.999% of the light which would have 100,000 times amplification.

Scaling it up for more power.

130 millinewtons per kilowatt (0.13 N/kw)

But 10 MW lasers would give 1300 newtons. Solid state lasers with 100KW should be completed this year and ones with 67 KW were already made. The laser propulsion can use an array of lasers. one hundred 100KW lasers is 10MW.

This is something that we can get ready post 2030+ when simply belt tightening to get more efficiency might be problematic.

The post was in response to no substitute for jet fuel or problems for chemical rockets.

Not fantasy: since the lasers work and the small power version of mirror lasers works. Scaling it up is engineering.

========

http://advancednano.blogspot.com

Yeah, sure. First of all, the potential of biofuel is really pitiful. Biofuels will never fuel even more than 10 to 20 percent of the global carfleet (and even that at a terrifying environmental and humanitarian cost). Secondly, there is really no replacement for kerosene. A kerosene replacement would require wider operating temperature range than available from biofuels.

I also used to be a great fan of science fiction. But lately I've turned towards pure fantasy, as it's easier to separate from reality.

- Jay

"If we lose the forests, we lose everything"

- Bill Mollison

Biomass gasification:

"Gasification can proceed from just about any organic material, including biomass and plastic waste. The resulting...syngas may be converted efficiently to...diesel-like synthetic fuel via the Fischer-Tropsch process."

It is unfortunate that oil was discovered before airplanes, as this makes it seem old-fashioned. Science-fiction schemes don't change the laws of chemistry. Kerosene, or its synthetic equivalent, is the only fuel with the required properties for aviation fuel:

- highest gravimetric energy density

- highest volumetric energy density

- non-toxic, non-carcinogenic

- non-corrosive to airframe materials (aluminum, epoxy)

- high flash point

- high liquid range

Other synthetic fuels have been tried; hydrazine, UDMH, liquid hydrogen, diborane etc.. None are safe *and* powerful enough. A modern airliner can be fueled at the gate while loading passengers, go from a +40C airport to -40C tropopause in minutes, and fly across the pacific non-stop, only because of kerosene.

Somewhere in a galaxy far, far away, alien creatures are flying around in kerosene fueled airplanes, because it is the only fuel that works.

Superb pragmatist engineering rant. I'm going to memorize the whole thing for use when extremely drunk in the company of arts-graduate scum.

Crank open that bottle oh plucky one I think you will need it, because you are in the presence of an art scum who kept the overdue library books rather than pick up the diploma. Now that is a real low life and much worse than a clean cut (relatively) arts-graduate. Anyhew the following for your august perusal:

Total Population of the World by Decade, 1950–2050

(historical and projected)

Year Total world population

(mid-year figures) Ten-year growth

rate (%)

1950 2,556,000,053 18.9%

1960 3,039,451,023 22.0

1970 3,706,618,163 20.2

1980 4,453,831,714 18.5

1990 5,278,639,789 15.2

2000 6,082,966,429 12.6

20101 6,848,932,929 10.7

20201 7,584,821,144 8.7

20301 8,246,619,341 7.3

20401 8,850,045,889 5.6

2050

http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0762181.htmlhttp://www.infoplease.com/ipa...

I am sure you will be able to figure out what this means being much above both pragmatic engineers and arts-graduate scum. But if you can't try that pragmatic engineer, I am sure he will walk you through it.

BTW I rather like dumb animals:)

In the previous crunch, we could (and did) turn to natural gas to replace the energy inputs to the economy. While oil consumption fell somewhat, total energy consumption fell much less.

We won't have that luxury this time around, particularly in North America.

Oh well! ... What those figures seem to show to me is that in 12 years between 1973 and 1985 the per capita worlds use of oil fell 19 % while in 10 years between 1970 and 1980 the world population rose by 18.5%. And if one crudely adds an extra two years of the next period of 10 years at that rate of 15.2% or 1.52% per year we get 18.5 + 3.04 = 21.9% increase in population. To hit this point on the head with a hammer, the world per capita use of oil fell because the world supply of people rose.

The arguments made by Robert for the present 'economic' structure is merely an argument for supporting capitalism and not what should be considered; preserving the world's economy. We stand by the world's grace not by how extraordinarily powerful, adept or guileful that machine, capitalism, is at sucking the blood out of this planet.

half full,

Kerosene was first discovered in the early 19th century when chemists were doing experimentation in England on coal gas for lighting. There's an awful lot of coal at mineable depths, certainly more than enough to ensre that the jets of the future will need pontoons to overcome the sea level rise from global warming (sarconal alert).

Source: Wikipedia article on coal gas

Also, we will never run completely out of oil. It may not be worthwhile except for specialty uses for which there are no other substitutes, but evn the most depleted oil fields will ooze a lttle forever and make perhaps 1/2 a barrel every couple of days with a timer and on a pump. The first major oilfield in the US, the Bradford field on the Pennsylvania/ New York state line sill has a few wells producing even though it was discovered just after the Civil War, and so does Corsicana the first major field in Texas and producing since 1890. Bob Ebersole

I vaguely recall that in the mid 1990s, workers at Edwards Air Force Base found several old corroded cylinders of pentaborane. (Or was it that they found that known cylinders had corroded?) I think they ended up blowing them up to avoid the danger of handling them.

You make an excellent point about the many advantages of keosene; I'd like to add that it's telling that even the US millitary uses kerosene for aviation (I'd expect them to be quite willing to make sacrifices in convenience to improve flight performance).

Pentaborane is, I guess, about as bad as day-old nuclear waste. It is much, much worse than year-old.

They blew those cylinders up remotely because a hot explosion would ignite the pentaborane, which had, of course, been expected to be useful, decades earlier, because of its very high heat of combustion. With air that includes some water vapour, it becomes boric acid ...

B5H9 + 6 O2 + 3 H2O ---> 5 B(OH)3

which you can buy at the drugstore. A few years before they blew up those tanks they learned the hard way that exposure to pentaborane, in the absence of a reliable ignition source, is death. One worker who got it all over his hands died. A second who came to his aid lost the use of his limbs, and IIRC, most of his mental faculties.

If the book-of-the-month club wants to sell you a really thick book that does not count as two of your three selections, but includes bound-in plastic sachets of any BxHy compound -- any "borane", as they are called -- don't forget to send in the refusal card.

--- G. R. L. Cowan, boron car fan

http://www.eagle.ca/~gcowan/boron_blast.html :

oxygen expands around boron fire, car goes

Less than a fifth for the cryotanks that have been demonstrated for cars. But the conclusion is false. If liquid hydrogen did not cost more per unit energy than kerosene, or not too much more, airliner makers would be all over it, because the much larger tanks in airliners allow container mass to be small compared to contents mass and airliners are not required to pass collision tests the way hydrogen BMWs, I seem to recall, have.

A slightly higher cost per joule would still end up cheaper for lH2 because a 100-tonne maximum takeoff mass aircraft with 60 tonnes non-fuel, 40 tonnes kerosene would, if the tanks were simply enlarged and thermally insulated to accommodate the equivalent 16 tonnes lH2, weigh at most 80 tonnes; the non-fuel mass fraction would thus be raised to 80 percent, and less of the fuel's energy would be spent on its own haulage.

This PDF looks like a competent treatment.

--- G. R. L. Cowan, boron car fan

http://www.eagle.ca/~gcowan/boron_blast.html :

How shall the car gain nuclear cachet?

My secret contacts at the NCSA borrowed me a few supercomputer hours and inform me that 60 non-fuel tonnes out of 80 total is actually 75 percent, not 80. Sorry.

--- G. R. L. Cowan, former hydrogen-energy fan

http://www.eagle.ca/~gcowan/Paper_for_11th_CHC.html :

oxygen expands around boron fire, car goes

Good points...I was trying to contact oil drum staff but the "contact" us link is not working. does anyone know how to contact them?

aherrera@anwr.org

Interesting post and I'm sorry I don't have the background to address the holistic point you are making but I have some comments about the micro.

The Futures market isn't a real market, is it? Because the future price can never rise above the arbitrage price cap, it is incapable of telling us much. The rare times the future price is below the arbitrage price cap, not THAT tells us something. The fact that it is rare, also tells us something.

I think the only way the downward side of the supply curve will be gentle, given currently accelerating demand, is if major suppliers start withholding supply now, if they aren't already. The smart ones should be. The basic economics supply/demand curves doesn't take this into account; shuns it, in fact as a "rational" notion.

The Minimum Operating Level difference between the U.S. and other parts of the world is a fascinating issue and so complex to compare in one article. I've spent a lot of time in Europe and would comment that the Europeans don't move around as much as we do in the U.S. at every level. Yes, there are large distances to cover, but they don't think of them the way we do. Partly this is the price of gas limiting them, but also it is cultural. If I tell a European that I regularly drive ten hours one-way to visit my parents, they stare at me as though I've grown an extraneous limb, and for me that's only a tank of gas in a Prius, and the diesel Peugots we regularly drive there get even better milage. Europeans like to live and die in the city they were born in so they don't have a familial draw to make them travel enmasse like we do. And more important their urban sprawl now overlaps so thoroughly as to make 100% public transit coverage viable in a way the U.S. will never be, even if we had the public policy wherewithall to actually try. (Case in point, why the heck isn't there high speed rail connecting all of the U.S. East Coast cities??) Another example: A Dutch friend of ours went on and on one visit about how he had found a temporary job in Amsterdam and would have to find, to his great distress, a second apartment there for the duration. Note that he lives in Rotterdam, a whole hour train ride away from Amsterdam. To him that was WAY too far to commute. So given that the U.S. mode of living will HAVE to change, we should be working harder to change it now, while the cost of changing the infrastructure are cheaper to change. Playing down the impact as you seem to be doing, isn't going to help.

I completely agree that rationing by price will save a lot of trouble all around, but I think it will save more if it happens pre-peak through supplies being withheld. I grind my teeth everytime a politician says they will lower the price of gas for voters. What ignorant and awful policy notion that is.

I have two elementary questions about the supply and demand curves...

First, why are they always shown as linear functions? I would think that for peak oil, the price would "explode" asymptotically at levels that represent a modest increase to current production. For example, I wouldn't be surprised if the price for doubling current production would be greater than the entire gross world product.

Second, why are changes to supply and demand shown as (simply) shifting the curves left or right, but not changing their slopes? I would think that the natural limits of oil availability would make the high quantity regions much steeper.

And why are they 2 dimensional?

Shouldn't we have N-dimensional differential equations with multiple solution nodes?

The supply and demand curves can be forward or backward bending, or any shape you like, like Paul Krugman's at the bottom of this article:

http://www.pkarchive.org/crises/opec.html

Generally straight lines keep it simple, and the aim of models is to simplify.

That is a feature of economists' communication, not of the data. Since they don't know the shape of the curve, they draw something simple. Yep, we engeneers have a bad time reading it, since for we a line is a line (if it wasn't linear, it would be curved)...

The slop changes, and the curves are finite, they have well defined start and stop points. Theoreticaly, there is a minimum cost of production, bellow what nothing is produced, and a maximum production capacity, when the society uses all its resources producing something. There is theoreticaly also a maximum amount of demand, since there is an up limit on the amount people can consume, and a maximum price anybody will pay for the product.

But those extremes poits never happen on practice, so economy isn't too concerned about them

Yet the very definition of economics is the study of scarcity, and in particular, the study of the efficient allocation of scarce resources.

Did they teach you that in college? Because everything you learn in college is crap. Economics is the study of making things sound complicated so you can steal and get away with it.

I am guessing you don't have a degree?

mkwin,

Nice ad hom attack. Totally unconvincing though.

If a person is reading TOD (as Petropest obviously is), we can assume that they have an education going beyond the formal grant of a sheeple's skin. After all, in college they don't (for the most part) teach us about Peak Oil and its perils.

I have a lot of college degrees.

I'm not willing to say that "everything" taught in school was "crap". After all, I did take courses in thermodynamics, in physics, in chemistry, etc.

But when it comes to "Egonomics", that was a loadfull of crap. I am only coming to understand that now in my geezer years. For much of my youth, I was as much an ardent believer in The Market and the Invisible Appendage as the next brain washed graduate of a cliff-side Higher Edge Occasion Institute.

Egonomics is addictively appealing because it has numbers and graphs and calls itself a "science" (of the dismal kind) and calls us "rational" consumers (of the utility maximizing kind). In hindsight, it's a piled higher dogdropping (PhD) of poop.

Good, thoughtful post.

I have one caveat, however: As prices rise, developing and poor countries will be under increasing pressure and may become increasingly unstable.

True, developed countries will back-pedal on their usage, seeking alternative sources and greater efficiencies. They will increasingly do so as the price rises. No end of the world for them....

However, because poor or developing countries are closer to the razor's edge, they will become more volatile, more chaotic, more prone to "terrorism." Terrorism will find its targets not only at home but abroad. Now, I use the term "terrorism" in the sense of "protest" and "counter-defense," not in the foolish way we often here it.

In defense, developed, rich countries will become more like enclaves...even while the pressure to accept more and more immigrants grows. As poor countries become more volitile, more and more people will seek the safer haven in the developed world. The developed world will, of course, have none of this.

The "good old times" may well be gone.

The question is: Can the transition to a less oil-centred economy or world be extended to the third world in such a way as to keep them from becoming exploding pressure cookers?

I do not see the leaders or the profiteers in the developed world responding enlightenly to these "pressure cookers." If Bush's War on Terror is the password, then we are indeed in for quite a ride. Indeed, the fact that these leaders and businessmen have no qualms about dirt cheap labor or cheap extraction of a poor country's resources tells me more than I want to know about their mindset.

Robert, where do you stand on the issue I have raised?

I would suggest to you that you and those at your level will have to speak loudly and boldly if we are to pass through this needle's eye safely. You will have to see "terrorism" and immigration pressures as natural responses to unforgivable conditions. Using only force to subdue them will only worsen them.

As an aside, I found the recent TOD post on Mexico's disintegration instructive.

However, because poor or developing countries are closer to the razor's edge, they will become more volatile, more chaotic, more prone to "terrorism." Terrorism will find its targets not only at home but abroad. Now, I use the term "terrorism" in the sense of "protest" and "counter-defense," not in the foolish way we often here it.

As an aside, I found the recent TOD post on Mexico's disintegration instructive.

The combination of these two actually is what bothers me. I'm worried there might be ripple effects. It's difficult to completely isolate bordering regions where a nation like the US meets a potentially unstable region such as Mexico. If one destabilizes, it could potentially generate significant issues in the neighboring nation. Does this make sense?

Forgive me if I'm out of line, I'm not a geologist or a petroleum engineer but I was trained as an aerospace engineer and I work as a systems engineer. I tend to see things on the big picture level and nothing in this area of concern is a "closed system".

Hi Bob,

Thanks for a great post. The forward pricing curve for oil was very interesting, and the optimistic tone provides balance.

Robert, you wrote:

But the evidence to prove the market is blind is there in the first graph. It tells us nothing about the actual price in the next 5 years does it?

If PO has happened there is nothing, nothing, that the oil forward curve will tell us until it suddenly spikes up on the "day of recognition" by a hundred dollars or more...

No, I shall not be using the 'oil forward curve' as a comfort blanket anytime soon thank you.

Regards, Nick.

Based on comments in the original article and several related posts, I think there are some misconceptions about the futures market and the futures forward curve for oil. In interest of full disclosure, I work for an investment management firm that participates in up to 5% of all the futures contracts traded globally on any given day not the mention the same fraction of global equity and currency trading. So, my viewpoint is unavoidably from the financial side of the table. And, if you are predisposed to distrust someone who earns a living in the financial markets, you have ample excuse to stop reading at this point. Nonetheless, I believe I have a realistic view of how the futures market operates.

First of all, contrary to popular opinion (and even Forbes and the WSJ make this mistake often), forward prices in the futures market do not represent price expectations. I know this point is going to be hard to accept, but the forward prices do not reflect the expected price movements of the underlying asset.

This realization is blantantly obvious if you take a look at the forward curve for the S&P 500 futures. The forward prices for the S&P 500 simply represent the current S&P 500 price plus the carrying cost of the position. Thus, the forward curve slopes up and then levels off. This is always the case for the S&P 500 futures. Everyday. All year round. The forward prices vary because of changes in the price of the underlying S&P 500 and future interest rate expectations. This behavior is typical for financial futures contracts. And since the underlying S&P 500 can be held both long and short, all of the price relationships along the forward curve are maintained within tight tolerances.

Futures contracts for physical commodities, on the other hand, are influenced by additional factors such as current inventories, seasonal supply and demand variations and by the hard constraint that it is impossible to be short the underlying commodity. That is, you cannot hold negative oil like you can hold negative stock (yes, you can hold negative stock). These differences allow the forward curves for physical commodities to behave somewhat differently than strictly financial assets. Since physical commodities cannot be hold short and are perishable (even oil in the pipeline must be comsumed in the short term), the carrying costs are often effectively negative. The relationships along the forward curve prices are not always maintained within the same tolerances and the curves often bend into funny shapes for pysical commodities.

You might wonder, what good are futures contracts if they do not reflect the future price expectations of the underlying asset. Well, that is a good question. Futures contracts allow one to lock in the cost/return of obtaining/supplying something in the future based on current conditions (i.e. mainly the underlying asset price and carrying costs). This explains why the futures market never predicts anything. The word "futures" is really is misnomer and causes untold confusion about how the market operates. The futures market is not designed to predict future prices, but simply to facilate future exchanges based on todays prices (notwithstanding the pure speculators who go into the market to make a quick buck) .

So, while I agree with the overall ideas in the article and do believe that you ignore the market at your own peril, I have to take exception with the concept that the uptick in the outer regions of the oil forward curve is pricing in an increase.

That said, if you want to get the market viewpoint on a price expectations, the options market will tell you everything you need to know. And, on average, the options market is reasonably accurate. Otherwise, the sellers of the options would go out of business.

I will try to post the predictions from the options market for oil prices later today. Due to time constraints, I am going to have to call it a night.

-mark

ps. As one futher example of the erroneousness (is that even a word?) of simpy interpreting forward prices as predictions: Traders buying the 2007 oil contract for $23 in 2002 did not think the price of oil was going to be $23 in 2007. I mean, if you go around buying assets that you expect to be worth $23 in 2007 for $23 in 2002, you are not going to last long.

TraderJoe,

I'm surprised you didn't mention Black-Scholes.

Isn't the future price determined by the current price, historical volatility of the asset, cost of holding and a pinch of salt?

As we approach 'the point of no return' volatility of the underlying asset price is going to go through the roof. The spreads on futures is going to get bigger and bigger. Someones going to make a lot of money, straddle that...

Nick.

Nick,

I did not mention Black-Scholes because it is used to price options, not futures.

Option contracts represent to the right, but not the obligation, to exchange assets at a fixed price at some point in the future. Futures contracts, on the other hand, represent the obligation to exchange assets at a specified time in the future.

You are correct that option prices are generally determined by the current price, volatility, carrying cost and, since 1987, "a pinch of salt". Before the 1987 market dislocation, option prices were based strictly on Black-Scholes which assumes a normal distribution of price changes. Immediately after the 1987 event, option pricing changed to take into account the non-normal distribution of price changes. But that is a little off the subject...

Futures prices are not governed by Black-Scholes and are not necessarily dependent on volatility since both parties are obligated to make the exchange. That is a significant difference between futures and options. Again, the word "futures" is really a red herring and provides for endless misdirection about what the forward curve means for a futures contract.

I agree that as we move forward oil prices are likely to become extremely volatile. And for those willing to take the necessary risks, that will provide opportunity for both innovation and profit.

Are you saying that calendar spreads (i.e. the price delta between oil contracts with different expirations) will increase? What is your reasoning here?

-mark

Maybe I'm reading this wrong, but it seems to discount the possibility that there is any speculative factor in the oil spot price. You seem to be saying the price is driven solely by the need to make supply and demand meet.

However, when a speculator buys oil, or oil futures, he/she is increasing demand. If, over a few months, many millions of people get clued in that oil production is going down down down forevermore, or if they get clued in the net exports are going to crash, they are going to buy some oil - not for storage and use, but for speculation. So, I can't agree with your anti-realization argument.

This whole post is calm calm calm, but, in real markets, panics happen. Oil prices will spike, and in general, get very volatile.

This post has opened up the controversy over rationing by price versus some other contrived system. On a global basis, we already have rationing by price in which those countries short of USD are reducing consumption so the newly emerging wealthy states such as China and India can have their increasing share. Any internal national rationing schemes - of which I am reluctantly in favor - will pale in comparison to an unregulated global market.

Because there is no world organizational body capable of rationing global consumption, it will be done by a combination of economics and belligerence. This is one argument for rationing; it's a lot less ugly than belligerence. The free market can 'fail' into things uglier than unfree markets. But we have chosen to paint everything with the free market brush, except the sacred cows of military contracting, corn production, public works and so on - not to mention the legion of tariffs and subsidies that still exist.

Free markets are great when supply and demand are similarly free. When they are not, a great question arises. Sharing a surplus is easy, a shortage not. Because oil is different from Rolex watches, those going without will also be subject to higher prices and possible shortages of such things as heat and foodstuffs while being too economically drained to invest in newer low energy consumption technologies. Americans are in the main inexperienced in the realities of actual shortages because there haven't been any. Until we get there, I wouldn't make too many assumptions.

History has examples of the demands of the rich being permanently destroyed at the hands of the poor. I like E F Shumacher's concept of a limit on wage differentials between the top and bottom being capped at about 5:1. This still allows for sufficient incentive to get to the top of the heap, but insures that if you want to make more, you have to take your underlings with you. CEOs get five times tha janitor's pay, but there is no limit on janitor's pay.

Social disharmony may be considered inevitable, but lots of things were considered inevitable a few hundred years ago that would be inconceivably so today.

Rationing was acceptable and successful during WW2, but if you think that the effects of looming shortages are going to be less messy, good luck. Personally, I''ll take the rationing and hold the mayo and the war. As for the invisible hand, lately it seems to be vacillating between scratching its head and picking its nose.

Are we due for the ghost of FDR in the form of the Ever Normal Refinery?

"As for the invisible hand, lately it seems to be vacillating between scratching its head and picking its nose."

In between slapping the poor upside the head.

Schumacher also argued that there was no economic theory for extractive industries. Conventional economics does not cover the use of finite resources rather than scarce resources. Therefore applying conventional economics to extractive industies produces the wrong policies.

While I know that the supply and demand curves shown are simplifications, it still made me think how less simplified supply and demand curves may look like, and I did the following considerations.

In the short term the supply is very rigid, even in a pre peak scenario. New oil field have a lead time of many years, even when there are known reserves, so new supplies will not come online immidiatly. This means that the supply curve is infinitly steep in the short term. After an oil peak, it will be infinitly steep even in the long term, since no more oil can be produced regardless of price.

Developing an oilfield require fairly high upfront investments, and the maintainance cost run even with no production, so a big portion of the fields will run on full capacity, even with fairly low prices. This is especially the case for deep sea offshore fields, like those in the North sea, and I would guess that it will also be the case for most of the fields owned by privatly owned companies. The only elasticity is provided by swing producers like Saudi Arabia. The curve will then look like below.

When the peak is passed, the supply ceiling will be lowered as the oil depletes (or in the diagram, move to the left)

Thanks for the report, one question though:

You compare world per capita oil consumption to world GDP. Shouldn't you be comparing it with world per capita GDP? Did this rise between 1973 and 1985?

It seems like it rose by about 40% between 1970 and 1985, or about 2.3% per year.

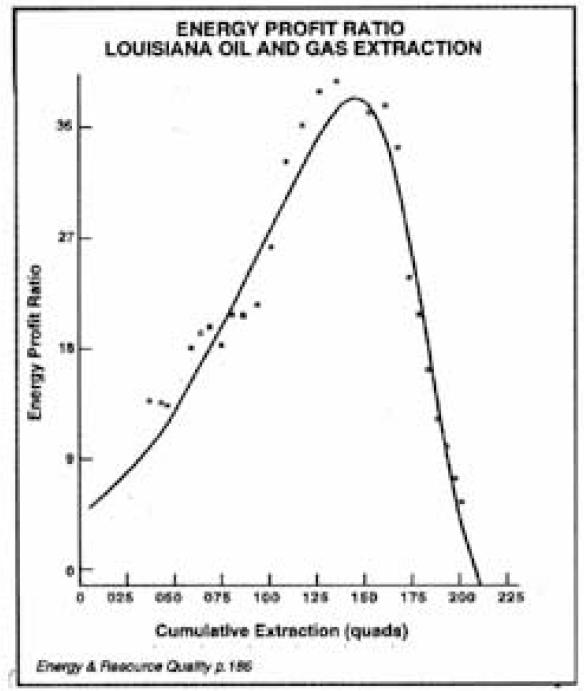

I am very pleased to see this point raised. So, When does the price of oil exceed the price of alternatives?

If we use EROI to estimate "production cost" then when does a lower EROI source replace a high EROI fossil fuel?

As you can see from this chart, a replacement with an EROI of 10 would not have a lower price until the fossil fuel source was almost entirely exhausted.

EROI

EROI

This assumption is supported by looking at the real world. Almost no alternatives are market competitive today. From memory Solar PV is $0.25 per KWh, Solar Concentrators are $0.12, Wind is $0.08 and Coal is $0.06. The moment that government price supports vanish, so do the alternatives.

The market alone will attempt a transition. But will there be enough time to build a huge new energy infrastructure while burning the last few scraps of low quality fuel?

Jon Freise

Analyze Not Fantasize -D. Meadows

Jon, I've seen this graph before from you but didn't really get what it was implying. I don't see what you say "can be seen from this chart..." -is the Y axis the EROI?? Sorry, must be thick Thursday today.

Nick.

It is my understanding that the Y axis is EROI and the X axis is cumulative production. (I don't have a copy of his book as it is out of print.) I took this chart from one of Nate's posts yesterday (but he has used it before).

So if the dollar cost of an energy source is related to EROI (and it must be in some way) then you can roughly predict when a new source will be competitive.

For instance, we know that Natural Gas has now risen high enough in price that Wind is cheaper. However, we also know that NG production is becoming more and more reliant on non-conventional sources. Sources which need more drilling, have poor flow rates, and fast declines. (thus low EROI).

Looking at NG predictions (by sliding the discovery curve forward) Jean Laherrère shows that NG in the US is nearly played out. Which is what one would expect if a lower EROI source is now competitive.

It seems to me the whole "Will Peak Oil and Gas turn out well" comes down to rates of change. What is the rate of decline in net energy? What is the rate of increase in alternatives? Once alternatives can stand on their own price wise, how much time do we have left to change? Is that enough time?

Jon Freise

Analyze Not Fantasize -D. Meadows

Exactly.

This is what sh*ts me the most about economic "analyses" of peak oil.

To use the physical analogy of market "forces" created through supply and demand and the pricing mechanism, the corresponding ideas of market "mass" and market "momentum" and "acceleration are entirely missing.

To use another physical analogy, the economic argument is an equilibrium argument where peak oil is a profoundly non-equilibrium, or kinetic, problem.

The issue is the *rates* at which these things will or will not happen. Adaptation to resource scarcity can only happen at a finite rate, and if that is slower than the rate at which the ground is shifting from under us then we are in very, very deep trouble.

I think you're onto something here. This is probably tied in with the economic concepts of price elasticity and demand destruction in some way.

I wonder if it would be possible to model this 'changeover inertia' using a parameter? The rate of decline in oil (say -2.5%) would be countered by the rate in increase of replacements/renewables (say +20%), the issue being that -2.5% of something very large is far far greater than 20% of something much smaller -hence massive demand destruction, resulting high prices and subsequant impact on the +20% figure...

The "Decline Inertia Impact" or DII model perhaps?

Nick.

Except of course if those 20% figures are extracted from a moment in time where those energy sources are still more expensive than the formers.

Now if those energy prices would be the same, or if they would be cheaper, will those 20% be mantained? Or will they skyrocket?

That's true, but there is a world of difference if this happens 20 years from now, or today.

Oil is rising rapidly in price, making all sorts of other scenario's possible. 20 years from now with oil above 80 $US, preferrably rising with something like 2-3x inflation is an almost foolproof scenario to mitigate peak oil.

In that case, peak oil will be something in the 'tin-foil-hat-conspiracy' blog-sphere, right where everybody would like it to be, including you and me.

And we would all go back and say: That was a horrible dream. Glad it's over.

On the other hand ... suppose it's not 20 years from now ...

Richard: Global oil supply has already peaked. We are currently past peak on the downslope. Whether or not the past peak supply can be exceeded in the future will be debated for years, but every month that global oil supply decreases makes it less likely, obviously. Finding new oil reserves will not ensure that the previous peak is exceeded-any reserves found will take a while to be productive, at which point current fields will have depleted further.

Brian,

I know, that's what it looks like. Just have a look at the IEA etc graphs.

But how do you really know KSA is in decline? Half of the country has not seriously been exploited. That's a big pile of sand out there. How about Iraq? More than a decade, well before peak oil was made popular, we boycotted the lot. Maybe there are large oil fields to be found, out there in the anbar etc.

Please remember, you only need a few cubic miles to mitigate peak oil. About a dozen cubic miles and PO is a non-issue. How about the deserts in the arab world where nobody really looked because oil was 10 US$ a barrel?

We could be at PO, but als maybe we just didn't really look for new oil yet.

Have you read "Twilight in the Desert?"

Assuming that Ghawar is in decline, it appears that every oil field that has ever produced one mbpd or more of crude oil is now in decline. The only confirmed new one mbpd or larger field on the (distant) horizon is the problematic Kashagan Field, which may be producing one mbpd or more some time after 2020.

In any case, in 1956 Hubbert noted that a one-third increase in estimated Lower 48 URR only postponed the projected Lower 48 peak by five years.

And beyond that, the one year increase from 2005 to 2006 in consumption by the top five net exporters was almost 400,000 bpd.

I think that there is a good chance that Saudi Arabia will show a double digit decline rate in net exports from 2006 to 2007.

Richard: Since this thread is supposedly about "economics" somebody should stick a fork in that tired cliche you are repeating which basically states that giant oil fields were not discovered because nobody was motivated enough to look for them (once the price of oil hits $100 or $200 or $10000 all of a sudden they will get off their butts and find those giants-that is how the invisible hand works). Are you aware that there is actually a relatively high negative correlation between the amount of money spent looking for oil and the amount of oil reserves actually discovered? Spending more money looking for oil does not appear to magically "produce" oil. Maybe an "economist" with 10 letters after his name can explain that enigma.

Look at an oilfield map of the Middle East. Most of the oilfields lie on a well-defined belt that runs SSE from Iraqi Kurdestan, through Kuwait, and then trends SE by East into the Saudi Eastern Province and the Emirates.

http://www.petroleum-economist.com/default.asp?page=19&searchtype=17&pro...

That is where the paleogeography worked out right to provide the highly specific coincidence of circumstances (source, reservoir and seal, continuous over large areas, followed by modest structuration as the Arabian impactor headed north, enough to form big anticlines but not enough to seriously mash things up) for the formation of supergiant oilfields.

Basically this province was the margin of what is known as the Tethys Sea, a narrow seaway of moderate depth that separated Africa from Europa. Lots of dead fish (source), coral reefs and deltas (reservoirs) and coastal salinas and sabkhas (evaporites, cap-rocks). In the same place, at different times, over millions of years. And all that delta deposition and reef-building loaded the Earth's crust enough to provide the subsidence that took everything down and heated it up to make ..... hmmmmm ..... (sniff) .....

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tethys_sea

Outside that belt, the conditions for the formation of supergiant oilfields don't obtain. There will surely be some localized small stuff, but that's true in almost any sedimentary basin. But don't dream about another Ghawar, or even another Abqaiq, because t'ain't gon'appen, mon. Expect to see plenty of hype aimed at gullible investors, though.

What rubbish, the Earths only 6000 years old. You'll be telling next we all descended from Monkeys! Haha ;o)

Nick.

I don't think we're in a position to know whether the transformation from less energy efficient industrialized economy to more energy efficient industrialized economy can occur without causing significant economic damage.

It depends in part on the pressures the system is under while the transformation occurs. It also depends on the kinds of steps that become part of the transformational process.

High prices are only part of the picture of incentivizing reallocation of energy consumption and investment in energy efficiency and conservation. Price rationing may give way to political pressure for different kinds of approaches for allocation of supply. Recessionary pressures may mount because of supply bottlenecks unrelated to price.

Thanks everyone,

re: "industrialized economy".

To really get an idea of effects, it seems like we might need to make some distinctions...consumption of industrialized energy inputs and goods v. manufacturing of such goods, etc.

The only issue I have with this statement is I think it understates the loss represented by sunk costs, i.e.: past investments that will either be tremendously devalued or lost altogether.

- Infrastructure built with no regard for anything other than the automobile.

- Suburban development that locks people in to a relatively fixed amount of driving and home energy use.

- An unhealthy reliance for over-the-road trucking for the bulk of US commerce.

- All manner of manufacturing and other economic activity sited based on the assumption that they can truck anything anywhere.

Hi Joe,

Thanks for making this point.